Kiki Juli Anggoro, School of Education and Center of Excellence on Women and Social Security (CEWSS), Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Thailand, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5519-3036

Annisa Laura Maretha, Deakin University, Victoria, Australia, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5677-6524

Anggoro, K. J., Maretha, A. L. (2025). Self-regulated learning in action: EFL student teachers’ approaches to managing an English club. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(3), 504–525. https://doi.org/10.37237/160303

Abstract

This study reports on the use of self-regulated learning (SRL) strategies by English as a Foreign Language (EFL) student teachers in managing English clubs. It explores how 65 student teachers apply SRL as both learners and instructors, focusing on key SRL components, strategies, and challenges. Data were collected through group and individual open-ended surveys at the conclusion of a 15-week project and were thematically analysed using MAXQDA software. This study examined student teachers’ perceptions of SRL, identifying key components such as independent learning, personal interests, time management, problem solving, and confidence. Independent learning was seen as the most important, emphasising autonomy and self-motivation, while personal interests were recognised for boosting engagement. Time management and problem solving were crucial for balancing tasks and overcoming challenges, with confidence growing over time. The study also highlighted three main SRL strategies: using technology, fostering collaborative learning, and conducting needs analysis to adapt instruction. Challenges included scheduling conflicts, low confidence, leadership difficulties, and cultural barriers.

Keywords: EFL; English club; Self-regulated learning; Student teachers

The landscape of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) education in Thailand continues to be shaped by several challenges, especially considering the limited opportunities for students to engage with English outside the formal classroom setting (Anggoro, 2025; Chang et al., 2023). Despite ongoing efforts to improve English proficiency through policy reforms, such as the introduction of the General Aptitude Test (GAT) and the Professional and Academic Aptitude Test (PAT) in 2009, Thai students often struggle with applying English in real-world contexts (Chang et al., 2023). Although recent initiatives, like the adoption of English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI) in higher education, have sought to address this issue, they have not fully resolved the persistent gaps in language proficiency, especially as influenced by socioeconomic disparities (OECD/UNESCO, 2016).

In response to these challenges, fostering self-regulated learning (SRL) has been identified as a promising approach to improving English language proficiency among students. SRL—where learners actively manage and direct their learning processes—has been shown to impact academic outcomes positively (Zimmerman, 2002). Incorporating SRL strategies into EFL instruction, particularly through interactive, student-driven activities such as English clubs, could provide future educators with valuable opportunities to enhance their language skills and engage with English in more meaningful ways. Therefore, incorporating student-led initiatives may also help EFL student teachers internalise the importance of SRL and integrate these strategies into their teaching practices, thus benefiting both their personal language development and their future students’ academic success. Such initiatives are especially effective because, to support the development of autonomy and self-regulation, it is essential to immerse learners in experiences that actively cultivate their independence and self-directed learning skills (Murray, 2014).

This article aims to explore how SRL can be integrated into the development of student teachers of English in a Thai university through an initiative—English clubs. By running these clubs, they engage in collaborative activities designed to enhance their skills while fostering SRL. The article will examine key aspects of SRL according to these student teachers after completing their 15-week project. It also reports the SRL strategies employed by them to successfully establish and run their clubs. In addition, the article will address the challenges faced by the student teachers during this process and offer suggestions for improving the initiative to better support the development of SRL skills. This exploration seeks to highlight the potential of initiatives to enrich EFL teacher education in Thailand and encourage a more self-directed approach to language learning.

Literature Review

Challenges in English Language Education in Thailand

English remains a foreign language taught in Thai schools and universities, yet challenges persist in its practical application. Despite the introduction of the General Aptitude Test (GAT) and the Professional and Academic Aptitude Test (PAT) in 2009, both of which include English proficiency components, Thai students continue to struggle with English language performance (Chang et al., 2023). This issue is compounded by many students carrying these academic challenges into university, reinforcing negative self-perceptions that discourage further improvement (Grubbs et al., 2009).

In recent years, efforts have been made to improve English instruction, particularly with the push for internationalisation and the adoption of English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI) in higher education (Chang et al., 2023). A study by Aizawa & Rose (2019) from another EFL context, Japan, reported that though these efforts have had an impact on classroom practices, they have not sufficiently addressed the root causes of underachievement, including institutional challenges such as rigid policies and standardised curricula, which continue to limit progress in learners’ language development.

Recent studies have shown that a significant factor contributing to the persistence of low English proficiency is socioeconomic disparity (Chang et al., 2023; Phothongsunan, 2019). The studies indicate that wealthier families have access to private tutoring, which provides an advantage in standardised testing, including English assessments, leaving students from lower-income backgrounds at a disadvantage. This disparity extends beyond standardised testing, affecting the ability of students from poorer families to access top-tier universities, further perpetuating the cycle of educational inequality (OECD/UNESCO, 2016). This narrow focus fails to accommodate the diverse proficiency levels among learners, which are influenced by socioeconomic disparities and the urban-rural divide in educational access (Pica, 2000).

Evolving Concepts of SRL

In the 19th century, education was seen as a rigid system where students’ failures were blamed on personal shortcomings rather than the curriculum structure itself (Zimmerman, 2002). However, with the rise of psychology in the late 20th century, educators began to recognise the importance of individual differences in learning. Reformers like Maria Montessori and John Dewey promoted alternative educational approaches, while research into metacognition and social cognition in the 1970s and 1980s highlighted the role of teacher guidance and instructional methods in fostering personal learning goals (Schunk, 1989; Zimmerman, 1989). As a result, there was a growing emphasis on student-centred learning (Schunk, 2005; Zimmerman, 2002). This shift redefined education, focusing on helping students overcome personal barriers to maximise their potential.

SRL emerged as a key concept, where students have the autonomy to actively control their learning process. Tassinari (2010) describes autonomy as a multifaceted and dynamic concept made up of several interrelated dimensions, including cognitive and metacognitive aspects, goal-directed actions, motivation, emotions, and social interaction. Self-regulated learners actively oversee and adjust their learning processes and behaviours to align with their goals and the demands of their learning environment (Pintrich, 2000; Zimmerman, 2002). They employ a diverse set of strategies, including metacognitive, motivational, and cognitive techniques, and effectively integrate these approaches to achieve their objectives (Pressley et al., 1987). A key aspect of self-regulation is metacognitive strategy knowledge (MSK), which involves understanding when, why, and how to use specific strategies to optimise learning (Veenman et al., 2006). Learners who regulate their learning effectively leverage these strategies to successfully navigate complex tasks (Hirt et al., 2021). Furthermore, they believe that their strategic approach directly influences their learning outcomes and that SRL skills can be cultivated through continuous practice and persistence (Hertel & Karlen, 2021)

Several studies have built upon the variables identified by Pintrich (2000) and other scholars (Hofer et al., 1998; VanderStoep et al., 1996) to enhance students’ self-regulation skills through targeted interventions. Interventions focusing on students’ goal orientations, learning strategies, self-monitoring, and self-evaluations have shown positive effects on self-regulation (Boekaerts et al., 2000; Schunk & Zimmerman, 1998). Complementing this perspective, Cotterall (2017) argues that fostering learner autonomy requires a learning environment that promotes engagement, authentic exploration, personalised relevance, reflective thinking, and scaffolded support. Similarly, Elliott and Dweck (1988) demonstrated that when children were given feedback on their abilities and exposed to a learning goal focused on developing competence, they chose more challenging tasks and applied problem-solving strategies. Several theoretical models emphasise that SRL involves the active interplay of metacognitive, motivational, and cognitive processes, allowing learners to exercise greater control over their learning (Boekaerts, 1997; Efklides, 2011; Pintrich, 2000). The metacognitive dimension of SRL is rooted in higher-order thinking, which enables learners to regulate their cognitive processes through introspection (Veenman et al., 2006). This dimension consists of two key components: regulatory strategies and knowledge. Regulatory strategies include planning (e.g., outlining an approach to a learning task), monitoring (e.g., tracking comprehension and maintaining focus), and evaluating (e.g., assessing performance and making necessary adjustments) (Nett et al., 2012). These strategies empower learners to take an active role in managing their thought processes and making informed decisions about information processing (Sharma et al., 2024). Thus, through SRL, learners gain a deeper understanding of their strengths and weaknesses, developing effective strategies not only for academic achievement but also for lifelong learning.

Several studies highlight the importance of considering individual differences in background characteristics when examining self-regulated learning (SRL). Research indicates that gender may influence SRL, with female students generally demonstrating higher metacognitive awareness and more frequent use of self-regulatory strategies than male students (Zimmerman & Martinez-Pons, 1990; Karlen et al., 2023). In the EFL context, Anggoro and Khasanah (2025) suggest that students’ acceptance of independent learning tasks may also be affected by their language proficiency. Socioeconomic status further shapes SRL capabilities, as students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds often exhibit greater metacognitive strategy knowledge and employ SRL strategies more frequently, possibly due to increased access to educational resources (Karlen et al., 2024). Additionally, Anggoro and Pratiwi (2025) propose that incorporating interactive media in both blended and online flipped EFL classrooms can enhance engagement, encourage reflective feedback, and support skill development, indicating potential benefits for fostering SRL through greater autonomy and active participation.

Method

Research Design

This study focuses on how student teachers of English engage with and develop SRL strategies through running their own English clubs. These clubs provide a valuable opportunity to demonstrate and engage in SRL. They also explore ways to foster SRL among their club members, who are university students from other disciplines. Through these experiences, the student teachers were hoped to gain a deeper understanding of how SRL could be integrated into their future classrooms, ultimately helping them teach their future students to become more self-regulated learners. The following research questions guide this study.

- What are the key aspects of SRL in running an English club?

- What SRL strategies do student teachers use in an English club, and how do these strategies contribute to their own development?

- What challenges do student teachers face in running an English club?

The present study is informed by a phenomenological approach, aiming to explore the lived experiences of student teachers of English as they develop SRL strategies in the process of organising and running English clubs over a 15-week semester. The participants of this study were 65 student teachers at a Southern Thai university, who were given a project to create and manage English clubs as part of their coursework. The structure of the project is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of Activities in the English Clubs Project

Further Information on Student-Run English Clubs

To create a club, student teachers could work individually, in pairs, or in groups of three to five. However, all of them opted to work in groups of three to five, and none chose the individual or pair options. They were also given the freedom to form their own groups. Concerning what each club looks like, rather than enforcing a predetermined structure, student teachers were provided with broad guidelines outlining the goal of promoting English communication. Instructors only specified that English should be the primary medium of communication during club activities and that the student teachers had to recruit at least five members with a low English proficiency level, CEFR A0, A1, and A2, from study programs other than English Education and English Literature. Beyond these core requirements, they had full autonomy in shaping their club’s format, content, and activities.

This approach led to the creation of diverse clubs, each incorporating English language practice in ways that aligned with student teachers’ interests. For example, those with an interest in fitness formed clubs such as “English at a Fitness Gym” and “Walking and English,” where English discussions were integrated into workout routines. Others, passionate about games, adapted activities like UNO and Monopoly by incorporating English vocabulary challenges into the gameplay. Additionally, socially oriented students organised informal clubs centred around casual conversation, gossip, and relationship-building, ensuring that English practice was incorporated in a natural and enjoyable manner.

Some students took their clubs online, utilising platforms like Roblox for English-language gaming or conducting sessions via Zoom to facilitate virtual interaction. Students with an interest in fashion created clubs where style tips were shared in English, while another group combined Thai dance lessons with English instruction, blending cultural engagement with language practice. Each club developed activities that were expected to make English communication not only relevant and engaging but also sustainable, allowing for the continuation of these clubs beyond the academic semester. This aligns with the finding of Mynard and McLoughlin (2020) that learners’ sustained engagement in self-directed language learning is closely linked to interest, which develops through both goal-defined and experience-defined motivation.

This approach to club creation and development reflects the integration of SRL, as the student teachers took the initiative, planned, and executed their own clubs. This process contributed to a dynamic and diverse range of language-learning opportunities. Through facilitating the club activities, the student teachers might develop their English proficiency further. In addition to doing the SRL themselves for the club creation, the student teachers also developed SRL activities for their club members. Some groups created one-page modules with vocabulary, expressions, and language functions to study before club activities. Others developed short videos or integrated interactive tools like Google Forms or Quizizz quizzes. The student teachers were encouraged to explore which SRL activities worked best for their club members, leading some clubs to adapt and modify their SRL tasks over time.

Data Collection

Data for this study were collected through open-ended surveys administered at the completion of the project. The surveys were designed to capture student teachers’ reflections on key aspects of SRL within the context of managing an English club, including the SRL strategies they employed and the challenges they faced. In Week 1, participants were informed of the study’s purpose, their expected contributions, and their rights, including the right to withdraw at any stage without penalty. Informed consent was obtained prior to participation, and a second confirmation was requested before survey completion, with a clear option to opt out. These procedures ensured voluntary participation, safeguarded autonomy and privacy, and complied with ethical research standards. The study utilised two types of surveys: group surveys and individual surveys.

Group Survey (Research Questions 1, 2, 3)

Before completing the group surveys, student teachers participated in a one-hour discussion based on the survey questions. This discussion allowed them to exchange insights, refine their perspectives, and clarify their thoughts. Afterward, they worked together to complete the survey in the classroom. Prior to this survey, the student teachers were already familiar with SRL from a previous course. They were also briefed on it during the first week of this project and reminded of the concept immediately before the group discussion and survey. The survey comprised three questions: (1) What do you consider the key aspects of self-regulated learning (SRL) when running an English club, and why are they important to your development as a student teacher? (2) What SRL strategies do you use in your English club, and how do these strategies contribute to your own learning and development? (3) What challenges do you encounter when applying SRL strategies in your English club?

Individual Survey (Research Questions 2 & 3)

In addition to the group surveys, individual surveys were administered to capture personal perspectives, as some students may have had unique experiences during the project that enriched the overall findings. These individual surveys were designed to address Research Questions 2 and 3, focusing on the SRL strategies student teachers employed and the challenges they faced during the project. Students were given a week to complete the survey, allowing for deeper reflection. The individual survey consisted of four open-ended questions: (1) How would you describe your English club in terms of learning activities and student engagement? (2) What aspects of your club do you think support self-regulated learning, and why are they effective? (3) What aspects of your club make it challenging to implement self-regulated learning, and why? (4) What strategies or changes could enhance self-regulated learning in your club?

Data Analysis

The data collected from both open-ended surveys were analysed thematically using MAXQDA, a qualitative data analysis software. All coding, including the identification of recurring patterns and key themes related to self-regulated learning strategies, student challenges, and reflections on teaching practices, was conducted within MAXQDA. The software facilitated systematic organisation and structuring of responses, ensuring that the emerging themes were well supported by direct student teachers’ quotes and examples. This approach provided a comprehensive understanding of participants’ experiences and allowed for an in-depth exploration of how SRL influenced their development as future EFL teachers.

Findings and Discussion

The findings presented here are derived from a combination of group and individual open-ended surveys and address all three research questions. A discussion is provided at the end of each section to analyse and interpret the results.

RQ1: What Are the Key Aspects of SRL in Running an English Club?

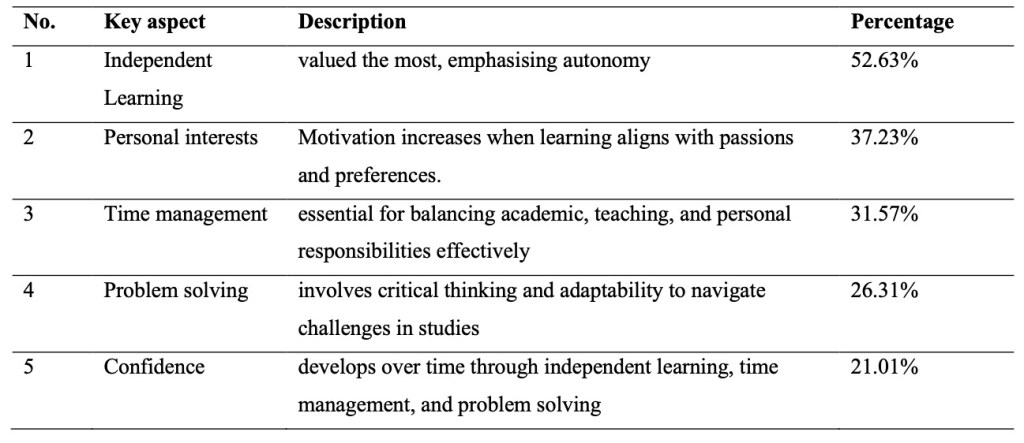

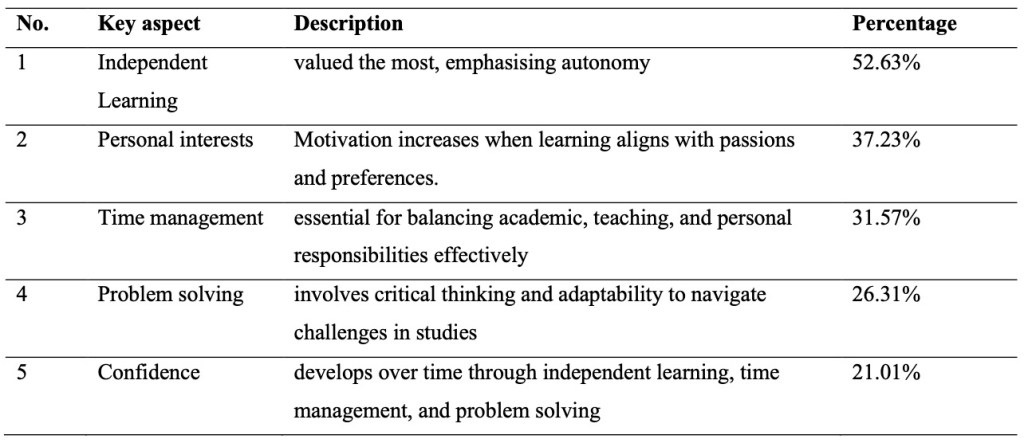

The group survey results indicated that student teachers viewed independent learning, personal interests, time management, problem solving, and confidence as key aspects of self-regulated learning in managing an English club (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Key Aspects of SRL Valued by Student Teachers (based on coded open-ended responses)

As shown in Table 2, independent learning emerged as the most frequently mentioned SRL aspect, appearing in 52.63% of student teachers’ open-ended responses. Many responses contained multiple themes, indicating a complex and overlapping understanding of SRL. The emphasis on independent learning might suggest that student teachers highly value autonomy and self-direction in their learning, as one participant noted, “SRL is very important for student teachers because it helps us take charge of our own learning” (ST3). Personal interests (37.23%) were also commonly mentioned, highlighting the motivational role of aligning learning with individual passions: “It allows students to become self-learners who can pursue their own interests” (ST8). Other valued aspects included time management (31.57%), problem solving (26.31%), and confidence (21.01%). For instance, a student teacher observed that “SRL skills help student teachers stay motivated and manage their time effectively” (ST11); another wrote “Self-regulated learning trains student teachers to make good decisions and solve problems when there’s an issue in managing tasks” (ST16). About confidence, one respondent commented, “EFL learners become more independent, confident, which is good for learning English language” (ST25). These findings indicate that student teachers experience SRL as a multifaceted construct that supports both practical learning strategies and personal growth.

As these excerpts show, SRL might have encouraged student teachers to take ownership of their learning by setting goals, planning their study time, monitoring their progress, and adjusting their strategies. This level of autonomy might not only benefit their individual learning but also prepares them to foster independent learning habits in their future students. Moreover, giving student teachers the flexibility to pursue their personal interests, rather than enforcing a rigid structure, might allow for diverse ways of integrating English into daily activities. Time management and problem solving were crucial components of SRL, as they enabled students to set clear goals and monitor their progress. In line with what Boekaerts et al. (2000) and Schunk and Zimmerman (1998) assert, interventions focused on enhancing goal orientation and learning strategies, such as effective time management, have been shown to positively influence students’ ability to regulate their learning. In this study, the English clubs were supported by targeted interventions from the lecturer, provided when necessary, such as offering guidance on how to structure activities, suggesting appropriate vocabulary, or helping student teachers resolve group coordination issues. Lastly, confidence seemed to be a potentially important factor, as student teachers suggested that the interactive and engaging nature of the English clubs might have contributed to enhancing SRL by making learning more enjoyable and motivating. The role of motivation in SRL, as discussed by Efklides (2011), is reflected in how the English club created a supportive, low-pressure environment for language learning. As Anggoro and Khasanah (2025) assert, activities such as team games and interactive media encourage students to practice English in a relaxed setting, boosting their confidence and willingness to engage in learning tasks. In essence, SRL appears to involve not only independent study but also participation in meaningful, structured activities that may foster motivation, problem solving, and confidence. The English clubs could serve as a practical example of how student teachers might implement SRL strategies in their future teaching, potentially supporting their future students in becoming more autonomous and effective learners.

RQ2: What SRL Strategies Do Student Teachers Use in an English Club, and How Do These Strategies Contribute to Their Own Development?

The results from individual and group surveys revealed several SRL strategies that student teachers employed while collaboratively managing an English club. These strategies are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

SRL Strategies Employed by Student Teachers in Managing an English Club (based on coded open-ended responses)

As shown in Table 3, one of the key strategies employed by student teachers in managing an English club was potentially the use of technology. Student teachers described various ways they approached technology, often noting its accessibility due to their familiarity with it. Several respondents reported that tools like podcasts, YouTube videos, online English courses, Pear Deck, and Kahoot might be useful for creating interactive and engaging activities. These tools, according to them, seemed to support tasks such as designing quizzes, reviewing answers, and reflecting on progress. Some student teachers expressed that using these tools potentially contributed to building their digital literacy and made them feel more prepared to integrate technology into their future classrooms. For instance, one participant shared that “using these platforms helped me become more confident in trying out new teaching tools” (ST28). Others indicated that experimenting with different tools allowed them to practice selecting and adapting resources, which they believed was an important skill for EFL teaching.

The second most frequently reported SRL strategy was collaborative learning. From the outset, participants appeared to enjoy working with peers; despite the flexibility in group size, no student chose to work alone, underscoring a clear preference for collaborative engagement. In the survey, they emphasised the value of debates, role-plays, and discussions, which were perceived as contributing to a positive learning environment and potentially fostering interaction and critical thinking. One student teacher group stated, “… facilitating group discussions helped me feel like a real teacher” (ST60). Several participants (ST27, ST33, ST45) noted that such strategies might also provide them with opportunities to develop leadership and facilitation skills. Through these experiences, they said they learned how to manage group dynamics, resolve conflicts, and encourage participation, key skills that will benefit their future teaching practices.

Lastly, student teachers also described the importance of needs analysis as a way to identify gaps in knowledge or areas that require more focus. Reflecting on these needs seemed to enable them to plan targeted interventions and select appropriate learning resources. One participant (ST49) explained, “I could adjust my teaching when I knew they were struggling with.” This process potentially helped them plan lessons more effectively, track progress, and address any gaps in learning. Reflecting on this process seems to have helped them adopt a more student-centred approach, as they learned to adjust their teaching methods based on the strengths and weaknesses of their learners.

The above excerpts gathered from the open-ended responses in the survey might illustrate how student teachers applied SRL in managing English clubs. They conceivably demonstrated metacognitive awareness in how they integrated regulated learning strategies. For example, one group commented, “Using podcasts, YouTube videos and shorts to learn through doing things in daily life, using quiz apps after lessons via Google Form and Pear Deck, playing games or reviewing lessons from Kahoot can monitor performance and adjust strategies in learning language” (G1). This shows the affordances of technology, such as language apps, online courses, and digital resources, to monitor their progress, reflect on their learning, and adapt their strategies accordingly. Another group (G3) wrote, “I would incorporate group activities like debates, role-plays, and discussions, where learners can practice speaking and problem solving in real-time.”

What has been exemplified by G1 and G3 are instances of metacognitive awareness, purposeful strategy use, and diverse cognitive engagement, reflecting key principles of self-regulated and collaborative learning (Pressley et al., 1987; Sharma et al., 2024; Veenman et al., 2006). G1 utilised digital tools such as Kahoot, podcasts, and quiz apps to monitor progress, adjust strategies, and engage with content in multiple ways, demonstrating an awareness of when, why, and how to apply learning strategies. G3 incorporated debates, role-plays, and discussions, providing opportunities for co-constructing knowledge, practising real-time problem solving, and refining cognitive skills through interaction. Together, these examples show how student teachers intentionally combined individual and collaborative strategies to achieve learning objectives, regulate their learning, and foster cognitive development. purposeful strategy use, reflecting key aspects of self-regulated learning as they both illustrate that the student teachers understood when, why, and how to apply learning strategies, regulating their learning in line with SRL principles. The emphasis on group work supports the idea that SRL skills can be cultivated through active engagement and continuous practice, as noted by Hertel and Karlen (2021).

Finally, needs analysis might play a crucial role in the motivational aspect of SRL. A group (G6) commented, “… quiz after lessons, set goals, and lay out strategies. Then, reflect on performance and think about the strategies. from previous performance to guide the next one.” By identifying individual learning needs, teachers might be able to help set realistic and relevant goals, thus potentially boosting students’ motivation and investment in their learning process. Understanding their needs might help students feel a sense of ownership and control over their learning, which is directly linked to motivation and persistence (Hertel & Karlen, 2021). Overall, the goal is to create a supportive learning environment where students are empowered to be autonomous, motivated, and self-aware, with the teacher acting as a facilitator of their growth (Pintrich, 2000). All the findings tentatively illustrate the integral role SRL plays in both the professional development of student teachers and the academic success of their future students.

RQ3: What Challenges Do Student Teachers Face in Running an English Club?

The challenges faced by student teachers can be categorised into four key factors: scheduling conflicts, low self-esteem, group dynamics and leadership issues, and cultural and social barriers.

One challenge faced by the student teachers was managing time and scheduling activities. Due to conflicting schedules, finding suitable meeting times became a considerable obstacle, especially when participants had different academic or personal commitments. A respondent wrote, “Time management because our free time is not compatible with each other” (ST6). Another commented, “Our weakness is finding people to do activities because our free time did not match up for most of us” (ST4). This challenge might not only hinder the planning of regular meetings and activities but also limit the ability to engage in collaborative efforts. Additionally, when appointments were made, logistical issues such as transportation delays or differing personal schedules often prevented members from fully participating.

Another challenge was low self-esteem in using English, which might have prevented some participants from fully engaging, particularly in activities that required speaking or presenting in English. Language barriers possibly hindered participation, as some members lacked the vocabulary necessary to engage comfortably in discussions or games. For example, one student teacher mentioned, “Some people don’t know or don’t understand some words when explaining to learn” (ST8), while another said, “I’m so shy, I’m not confident to speak” (ST14). Similarly, another student noted, “Some friends don’t have enough confidence to speak English” (ST37). These communication challenges might have limited active participation and decreased the overall effectiveness of group activities.

The leadership and group dynamics of the club also presented challenges. Several members might have struggled with taking on leadership roles, especially given that this might be their first experience organising and managing activities. This lack of leadership experience conceivably made it difficult for the club to function smoothly and cohesively. A student teacher mentioned, “We don’t have a lot of members, and I think we don’t have the skills to lead the activities because it’s our first time” (ST12). Additionally, a respondent wrote, “All of our members are introverts” (ST32). The predominance of introverted members might mean that many participants were less likely to take charge or engage in collaborative decision-making. This resulted in a lack of direction and less dynamic participation from the group as a whole.

Cultural and social differences might also play a role in limiting the effectiveness of the clubs’ activities. Some participants were hesitant to engage in certain activities due to fear of making mistakes or cultural discomfort. A student teacher commented, “Some of my friends who come to study don’t dare to speak because they are afraid of making mistakes” (ST36). Another mentioned, “Some people may have different preferences or might be uncomfortable with certain cultural activities, such as Thai dancing” (ST52). Since Thai culture places great importance on avoiding embarrassment (Phongthongsunan, 2019), that might have made some Thai students hesitant to speak, especially in a foreign language where they feared being judged. Also, they might not have opportunities to practice English in real-life situations, making them more anxious when required to speak in front of their peers. These fears potentially discouraged involvement and reduced the overall sense of community within the clubs, making it harder for members to bond and fully engage in the learning process.

Previous studies have emphasised that these challenges often stem from variations in goal orientations and learning strategies (Boekaerts et al., 2000). Students from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds may struggle to synchronise their learning approaches with social interaction strategies, hindering their ability to recognise biases or adapt to sociocultural norms in learning, and thus impacting collaboration and group work (Efklides, 2011). For example, a deep-seated fear of making mistakes, often instilled during high school (Phothongsunan, 2019), can cause students to refrain from asking questions or engaging in discussions on digital platforms, leading to passive learning (Boekaerts et al., 2000). According to SRL theories, a lack of self-regulation might contribute to a fixed mindset, making it more difficult for students to develop their communication skills over time (Schunk & Zimmerman, 1998). Additionally, without metacognitive regulation, students may struggle to critically analyse challenges and generate innovative solutions (Pintrich, 2000). Therefore, this paper argues that the deliberate integration of SRL strategies might be essential to encourage learners to actively regulate their learning rather than depend solely on external resources or group dynamics. This approach can potentially help address barriers in communication, leadership, and cultural adaptation, ultimately fostering more self-sufficient and adaptable learners.

Conclusion

This study explored student teachers’ perceptions of self-regulated learning (SRL), revealing that they view independent learning, personal interests, time management, problem solving, and confidence as key components of effective SRL. Among these, independent learning emerged as the most valued aspect, emphasising autonomy and self-motivation, while personal interests were seen as crucial for enhancing engagement. Time management and problem solving were considered essential for balancing responsibilities and overcoming challenges, with confidence developing over time. To support their SRL practices, student teachers identified three main strategies: leveraging technology, promoting collaborative learning, and conducting needs analysis to tailor instruction. In this study, collaborative learning strategies provided opportunities to peer interaction, allowing them to apply and reinforce their understanding of the material. However, they also described facing challenges such as scheduling conflicts, low confidence, leadership difficulties, and cultural barriers.

The implications of these findings stress the importance of integrating key strategies into educational practices to enhance SRL. Encouraging autonomy by allowing them to explore personal interests might significantly increase motivation and engagement. Educators should also focus on incorporating time management and problem-solving skills to help students set clear goals and overcome challenges. Technology, such as podcasts, YouTube, and interactive tools like Pear Deck, should be leveraged to support independent learning and boost student engagement. Collaborative learning activities like debates and role-plays are potentially essential for developing communication and leadership skills while fostering teamwork. To address barriers like low self-esteem and language challenges, educators may create inclusive environments that encourage participation and promote a growth mindset. For example, small-group discussions, role-plays, scaffolded speaking tasks, and positive feedback might boost confidence. Teachers can also use sentence starters, visual aids, and vocabulary lists to support participation and reduce language barriers. Also, regular needs analyses can potentially allow instruction to be tailored to students’ individual needs, enhancing motivation and making learning more relevant. Teachers can conduct these periodically and survey students about difficult topics or their learning problems to design targeted activities. Moreover, cultural sensitivity should be considered when designing SRL activities to ensure they are accessible and engaging for all students. Lastly, teacher training programs should prioritise SRL strategies, equipping future educators to model these skills for their students and foster lifelong learning.

Despite these insights, the study has several limitations. Although the sample size was reasonably robust, the reliance on self-reported data may introduce bias, as responses reflect participants’ perceptions rather than observed behaviours. The study focused on a single institution, which may limit the generalisability of the findings to other EFL contexts. Additionally, the research did not account for participants’ gender or socioeconomic background, which may influence the ways in which SRL strategies are applied and perceived. Variations in prior English proficiency and access to technology were also not controlled. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design captures only a snapshot of SRL practices, leaving longer-term development unexplored. While the findings highlight potential benefits of SRL, these limitations suggest caution when interpreting the results. Future research could consider broader and more diverse participant characteristics or adopt experimental or longitudinal designs to corroborate self-reported data.

Notes on the Contributors

Kiki Juli Anggoro is an Assistant Professor at the School of Education at Walailak University, Thailand. He holds a B.Ed. in English Language Teaching from Yogyakarta State University, Indonesia, as well as an M.Ed. and Ph.D. in Educational Technology and Communications from Naresuan University, Thailand. His research interests focus on technology-enhanced language learning (TELL), flipped classrooms, self-regulated learning, gamification, interactive response systems, and the integration of generative AI in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) instruction.

Annisa Laura Maretha is a PhD candidate in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Deakin University. Her research spans pragmatics, sociolinguistics, critical discourse analysis, and English language teaching (ELT). She is currently exploring the sociolinguistic dynamics of Indonesian Muslim women influencers in digital spaces, while maintaining a strong interest in ELT practices and teacher education, including learner autonomy and self-regulated learning.

References

Aizawa, I., & Rose, H. (2019). An analysis of Japan’s English as medium of instruction initiatives within higher education: The gap between meso-level policy and micro-level practice. Higher Education, 77(6), 1125–1142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0323-5

Anggoro, K. J. (2025). Navigating the integration of generative AI in EFL teaching: An autoethnographic journey with the flipped classroom model. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(1), 237–250. https://doi.org/10.37237/160112

Anggoro, K. J., & Khasanah, U. (2025). Nearpod interactive video as an independent learning tool in a flipped writing course in a Thai university. Computer-Assisted Language Learning Electronic Journal, 26(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.54855/callej.252612

Anggoro, K. J., & Pratiwi, D. I. (2025). EFL students’ perceptions of interactive slides (Pear Deck) in blended and online flipped classrooms. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 12, 101887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2025.101887

Boekaerts, M. (1997). Self-regulated learning: A new concept embraced by researchers, policy makers, educators, teachers, and students. Learning and Instruction, 7(2), 161–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(96)00015-1

Boekaerts, M., Pintrich, P. R., & Zeidner, M. (2000). Handbook of self-regulation. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50042-1

Chang, T.-S., Haynes, A. M., Boonsathirakul, J., & Kerdsomboon, C. (2023). A comparative study of university students’ ‘English as medium of instruction’ experiences in international faculty-led classrooms in Taiwan and Thailand. Higher Education: The International Journal of Higher Education Research, 86(6), 1341–1362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00975-w

Cotterall, S. (2017). The pedagogy of learner autonomy: Lessons from the classroom. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 102–115. https://doi.org/10.37237/080204

Efklides, A. (2011). Interactions of metacognition with motivation and affect in self-regulated learning: The MASRL model. Educational Psychologist, 46(1), 6–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2011.538645

Elliott, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.5

Grubbs, S.J., Chaengploy, S, & Worawong K. (2009). Rajabhat and traditional universities: Institutional differences in Thai students’ perceptions of English. Higher Education, 57 (3), 283-298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9144-2

Hertel, S., & Karlen, Y. (2021). Implicit theories of self‐regulated learning: Interplay with students’ achievement goals, learning strategies, and metacognition. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(3), 972–996. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12402

Hirt, C. N., Karlen, Y., Maag Merki, K., & Suter, F. (2021). What makes high achievers Different from low achievers? Self-regulated learners in the context of a high-stakes academic long-term task. Learning & Individual Differences, 92, 102085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2021.102085

Hofer, B., Yu, S., & Pintrich, P. R. (1998). Teaching college students to be self-regulated learners. In D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmermann (Eds.), Self-regulated learning: From teaching to self-reflective practice (pp. 57–85). Guilford.

Karlen, Y., Hertel, S., Grob, U., Jud, J., & Hirt, C. N. (2024). Teachers matter: Linking teachers and students’ self-regulated learning. Research Papers in Education, 40(3) 414–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2024.2394059

Karlen, Y., Hirt, C. N., Jud, J., Rosenthal, A., & Eberli, T. D. (2023). Teachers as learners and agents of self-regulated learning: The importance of different teachers competence aspects for promoting metacognition. Teaching and Teacher Education, 125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104055

Murray, G. (2014). The social dimensions of learner autonomy and self-regulated learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(4), 320–341. https://sisaljournal.org/archives/dec14/murray/

Mynard, J., & McLoughlin, D. (2020). “Sometimes I just want to know more. I’m always trying”: The role of interest in sustaining motivation for self-directed learning. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 17(1), 79–92. https://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/docroot/v17s12020/mynard.pdf

Nett, U. E., Goetz, T., Hall, N. C., & Frenzel, A. C. (2012). Metacognitive strategies and test performance: An experience sampling analysis of students’ learning behavior. Educalion Research International, 958319. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/958319

OECD/UNESCO. (2016). Reviews of national policies for education: Education in Thailand an OECD-UNESCO perspective. OECD Publishing.

Phothongsunan, S. (2019). Revisiting English learning in Thai schools: Why learners matter. NIDA Journal of Language and Communication 24(35), 97–104. https://lcjournal.nida.ac.th/main/public/abs_pdf/jn_v24_i35_6.pdf

Pica, T. (2000). Tradition and transition in English language teaching methodology. System, 28(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00057-3

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds), Handbook of self-regulation, 452–502. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50042-1

Pressley, M., Borkowski, J. G., & Schneider, W. (1987). Cognitive strategies: Good strategy users coordinate metacognition and knowledge. Annals of Child Development, 4, 89–129.

Schunk, D. H. (1989). Self-efficacy and achievement behaviors. Educational Psychology Review, 1(3), 173–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01320134

Schunk, D. H. (2005). Self-regulated learning: The educational legacy of Paul R. Pintrich. Educational Psychology, 40, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4002_3

Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (1998). Self-regulated learning: From teaching to self-reflective practice. Guilford.

Sharma, K., Nguyen, A., & Hong, Y. (2024). Self-regulation and shared regulation in collaborative learning in adaptive digital learning environments: A systematic review of empirical studies. British Journal of Educational Technology, 55(4), 1398–1436. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13459

Tassinari, M. G. (2010). Autonomes Fremdsprachenlernen: Komponenten, Kompetenzen, Strategien [Autonomous language learning: Components, competences, strategies]. Peter Lang.

Vanderstoep, S. W., Pintrich , P. R., & Fagerun, A. (1996). Disciplinary differences in self-regulated learning in college students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 21, 345–362.

Veenman, M. V. J., van Hout-Wolters, B. H. A. M., & Afflerbach, P. (2006). Metacognition and learning: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Metacognition and Learning, 1, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-006-6893-0

Zimmerman, B. J. (1989). A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning. J. Educational Psychology, 81, 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.81.3.329

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into practice, 41(2), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2

Zimmerman, B. J., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1990). Student differences in self-regulated learning: Relating grade, sex, and giftedness to self-efficacy and strategy use. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.51