Shotaro Ueno, Academic Success Center, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1532-7367

Siwon Park, Faculty of International Liberal Arts, Juntendo University, Japan. https://orcid.org/0009-0004-5561-4162

Ueno, S., & Park, S. (2025). Exploring the relationship between self-regulation, grit, motivation, and English proficiency among university students in Japan. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(2), 418–436. https://doi.org/10.37237/160208

Abstract

While previous studies on self-regulated learning (SRL) in the second and foreign language (henceforth L2) have accumulated numerous empirical findings showing that variables related to SRL have a significant impact on L2 learning, the majority of these studies have been conducted in limited contexts such as Hong Kong and China and have predominantly focused on specific skills such as vocabulary and writing. In order to broaden the understanding of the relationship between SRL and L2 learning across different learning skills and contexts, the current research aimed to examine the relationship between SRL and English proficiency among first-year university students (n = 47) from an English-related major at a Japanese private university. Our research used a questionnaire to measure SRL variables, including self-regulation, grit, and motivational variables (i.e., self-efficacy, intrinsic value, and growth mindset), and TOEFL test scores to measure English proficiency. The results showed that although Bayesian Kendall’s tau correlation analysis provided some support for the relationships between certain aspects of self-regulation, such as awareness, goal setting and management, and emotion control, and their relationships with self-efficacy and grit, no correlations was found for most variables. These results contrast with findings from some previous studies conducted in non-Japanese contexts. The inconsistent results across studies may be attributed to contextual differences. Based on these findings, implications for future L2 SRL research are discussed and considered.

Keywords: self-regulated learning, self-regulation, grit, self-efficacy, intrinsic value, growth mindset, TOEFL scores, Bayesian Kendall’s tau correlation analysis

Over the past decade, self-regulated learning (SRL) research has been widely conducted in the field of second and foreign language (henceforth L2) learning and teaching (e.g., Bai & Guo, 2018; Guo et al., 2023; Park et al., 2025; L. S. Teng & Zhang, 2016; Ueno & Takeuchi, 2022). SRL refers to “the ways that learners systematically activate and sustain their cognitions, motivations, behaviors, and affects, toward the attainment of their goals” (Schunk & Greene, 2018, p. 1). The increasing focus on SRL research in L2 arises from the understanding that mastering an L2 requires significant effort, particularly in environments with limited opportunities for input and output. In this sense, more strategic and autonomous L2 learning, such as SRL, is necessary to achieve such goals. SRL skills enable learners to engage in English learning not only inside the classroom but also beyond it, in alignment with their learning goals (e.g., in self-access learning contexts).

Previous research on SRL in English as an L2 has extensively explored the intricate relationships among various facets of English learning, encompassing metacognitive, behavioral, and affective dimensions, and has suggested that enhancing these interrelated variables promotes proactive and autonomous English learning (e.g., Bai & Wang, 2023; Graham et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2023; Ueno & Takeuchi, 2022; see Ueno et al., 2025 for a recent comprehensive review). Among the SRL variables, a substantial body of research has demonstrated the significant impact of self-regulation, grit, and motivational factors (i.e., self-efficacy, intrinsic value, and growth mindset) on self-regulated English learning and achievement (e.g., Bai & Guo, 2021; Bai & Wang, 2021, 2023; Guo et al., 2023; M. F. Teng et al., 2024), and these variables have become key benchmarks for researchers and teachers to consider when conducting research on this topic or supporting learners’ SRL in L2 learning.

Despite these advancements in L2 SRL studies, the existing evidence has several controversial aspects. One critical issue is the setting in which the studies were conducted. To our knowledge, the majority of existing SRL studies have been conducted in very limited regional contexts, such as Hong Kong (e.g., Bai & Guo, 2021; Bai & Wang, 2023; Guo et al., 2023) and China (e.g., Xu & Wang, 2022; Zhao et al., 2023). Given that motivations, beliefs, and L2 learning strategy use are possibly influenced by cultural values, social norms, learning environments, and educational systems (Bai & Wang, 2021; Takeuchi et al., 2007), the relevant variables of SRL in L2 may vary depending on the learning environment in which learners are placed (Ueno & Takeuchi, 2022). Therefore, SRL studies in a greater diversity of L2 environments are needed to strengthen the theory and to consider how instruction incorporating the SRL framework should be implemented in diverse L2 contexts.

The second critical issue relates to the target English skill addressed in the existing studies. To date, while the majority of SRL studies have focused on writing (Bai & Guo, 2021; Bai & Wang, 2021; L. S. Teng & Zhang, 2016) and vocabulary (M. F. Teng et al., 2024; Tseng et al., 2006; Tseng & Schmitt, 2008; Ueno & Takeuchi, 2022), very few studies have been conducted on other areas of English learning. Thus, more studies on skills other than writing and vocabulary are important to gain valuable insights into how to promote SRL in different skills of English learning.

Given the aforementioned limitations of prior SRL studies, the current research targeted Japanese university students learning English as a foreign language (EFL). It examined whether the variables of SRL, including self-regulation, grit, self-efficacy, intrinsic value, and growth mindset, were related to their English proficiency. English proficiency was measured using TOEFL ITP scores, which assess skills such as listening, reading, and grammar. In this way, our research attempted to address the limitations of previous studies by comparing the results of this research with previous findings on students from other nations and on writing and vocabulary skills.

Literature Review

Self-Regulation

Self-regulation is the ability to control and manage emotions, goals, environment, and even concentration during learning (Tseng et al., 2006; Tseng et al., 2017). Learners with stronger self-regulation are believed to be more proactive, resourceful, and effective in carrying out learning tasks (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2011). Thus, by developing learners’ sense of self-regulation, their motivation to learn subject matter is more easily sustained against competing motivations, distractions, and procrastination (Pintrich, 1999; Tseng et al., 2017).

Not only does the use of self-regulation skills or related strategies promote learner motivation, but previous studies have also shown that these skills and strategies are fostered by learner motivational factors such as self-efficacy, intrinsic values, and growth mindset (e.g., Bai & Wang, 2021; Guo et al., 2023). Thus, these findings suggest the importance of self-regulation and motivational factors interacting to sustain active learning and achieve better performance, and self-regulation skills have been considered the core component of SRL in L2 learning and teaching.

Motivational Variables and Grit

Intrinsic value and self-efficacy have long been considered critical motivational variables (also referred to as motivational beliefs) for promoting behavioral/cognitive and metacognitive aspects of SRL in L2 (e.g., Bai & Guo, 2021; Bai & Wang, 2023; Guo et al., 2023; Pintrich & De Groot, 1990). The two motivational variables are primarily theorized by the expectancy-value model (Eccles, 1983; Pintrich, 1989; Pintrich & De Groot, 1990). This model consists of three motivational components that are possibly related to different aspects of SRL, including an expectancy component, a value component, and an emotional component (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990).

The expectancy component refers to learner’s beliefs about their ability to successfully perform given tasks (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990), which includes self-efficacy or beliefs about one’s ability to successfully perform certain tasks according to one’s abilities (Bandura, 1997). The value component is related to the learner’s goal or belief, which is driven by the learner’s perception of the importance and interest of the task. Intrinsic value, which refers to the learners’ intrinsic interest in learning, perception of the importance of the coursework, and preferences for challenge and mastery goals, is considered a critical factor for this component (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990). The emotional component is related to the learner’s emotional response, such as anxiety, fear, pride, and anger (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990). Although Pintrich and De Groot found that self-efficacy (i.e., the expectancy component) and intrinsic value (i.e., the value component) were strongly correlated with strategy use and self-regulation, test anxiety (i.e., the negative emotional component) was not correlated with strategy use and was negatively correlated with self-regulation. Subsequent studies have further supported that self-efficacy and intrinsic value have positive effects on SRL in L2 (e.g., Bai & Guo, 2021; Bai & Wang, 2023; Liem et al., 2008). These empirical findings have theorized the importance of self-efficacy and intrinsic values in L2 SRL.

Although learner mindset is a relatively novel variable introduced into L2 research, it has the potential to be associated with the promotion of SRL in L2 (e.g., Bai & Guo, 2021; Bai & Wang, 2023). The concept of mindset theory is founded upon implicit theories, which assumes the malleability of personal qualities (Dweck & Leggett, 1988). The theory posits two distinct facets of learners’ mindsets: a growth mindset and a fixed mindset. A growth mindset is defined as the belief that intelligence is malleable and can be developed through effort, whereas a fixed mindset refers to the belief that intelligence is static and cannot be altered (Dweck, 1999; see Macnamara & Burgoyne, 2023 for a recent review). The theoretical assumption is that learners with a fixed mindset believe that their intelligence is innate and immutable. In contrast, learners with a growth mindset believe that their intelligence is malleable and that it can be changed or promoted by their efforts (Dweck, 1999; Dweck & Yeager, 2019; Khajavy et al., 2020; Papi et al., 2021). In the context of L2 learning, previous studies have demonstrated that a growth mindset has a positive effect on L2 performance, while a fixed mindset has a negative effect on performance (e.g., Khajavy et al., 2020; Papi et al., 2021). It is, therefore, generally accepted that those who perform better in L2 learning tend to have a growth mindset, whereas those who perform less well tend to have a fixed growth mindset (Bai & Guo, 2021).

Grit is another variable that has been associated with promoting SRL in L2 contexts (Guo et al., 2023). The concept of grit was originally introduced in the field of educational psychology (Duckworth et al., 2007) and is defined as “perseverance and passion for long-term goals” (p. 1087). Duckworth et al. suggest that grit is positively functional because it is related to engagement in tasks by sustaining effort and interest over the years despite failure, difficulty, and slowed progress. The importance of grit has been recognized in a broader field of research (Pawlak et al., 2022), and empirical findings have accumulated to support this idea (e.g., Duckworth et al., 2007; Wolters & Hussain, 2015).

When it comes to L2 research, many researchers have acknowledged the importance of grit in L2 learning (e.g., Keegan, 2017; MacIntyre & Khajavy, 2021; Teimouri et al., 2022), and existing studies have shown that greater grit tends to have a positive effect on passion for L2 learning and confidence in L2 ability (Lake, 2013), higher L2 learning performance (Khajavy et al., 2020), and the use of SRL strategies (Guo et al., 2023). These findings suggest the positive contribution of grit to L2 learning and its potential impact on SRL in L2.

The Current Study

The current study was motivated by two related gaps in previous studies on the relationship between variables related to SRL and English proficiency: (a) the limited number of SRL studies targeting students other than those from Hong Kong and China, and (b) the lack of SRL studies focusing on skills other than writing and vocabulary.

Following previous studies related to this topic (e.g., Bai & Wang, 2023; Guo et al., 2023), we collected data quantitatively by using a questionnaire (created with Google Form) to measure each variable of SRL in L2 learning (i.e., self-regulation, grit, self-efficacy, intrinsic values, and growth mindset) and by using the scores of the TOEFL test administered at the target students’ university. We conducted a correlation analysis with Bayesian estimation to explore the potential for relationships between these variables, with the aim of contributing to the existing body of knowledge in this field. Based on the previous findings of correlations or causal relationships between SRL variables used in our research (e.g., Bai & Guo, 2021; Bai & Wang, 2023; Fathi et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2023; Khajavy et al., 2020; Lou et al., 2022; Teimouri et al., 2022; Xu & Wang, 2022), we hypothesized that relatively stronger correlations between the variables would be confirmed with Bayesian posterior support (i.e., correlation coefficients stronger than r = .40, which is considered a medium effect size according to Plonsky and Oswald’s (2014) criteria). Our research formulated research questions (RQs) as follows:

RQ1: Are there any relationships between variables related to SRL and English proficiency (i.e., the TOEFL scores) among Japanese EFL university students?

RQ2: What are the relationships between students’ self-regulation, grit, and the three motivational variables (i.e., self-efficacy, intrinsic value, and growth mindset)?

Method

Participants

The study involved 51 first-year university students (13 males and 38 females) from a private university in Japan. Notably, all participants in the study were enrolled in the same English program and were from an English-related major at the university. Thus, the students may have had more opportunities to use their target L2 and learn about different cultures and international issues in their daily lives as well as in their classes. The students’ ages ranged from 18 to 24 years old (M = 18.94, SD = 0.87). Most of the students started learning English in elementary school (n = 27), junior high school (n = 12), or kindergarten (n = 10). With the exception of one student, the students’ first language was Japanese. Students who had lived in English-speaking countries for more than one year were excluded from the current research to avoid potential confounding factors. As a result, a total of 47 students’ data remained, and they were used in the data analysis.

Measures

English Proficiency

The TOEFL ITP test was used to determine the students’ English proficiency. This test has three sections, including listening, grammar, and reading, and the maximum score is 667. The TOEFL test is widely used to determine the English proficiency of students who want to study English abroad, especially in the U.S. The average score of the students was 457.59 (SD = 35.11), which corresponds to the B1 level of the CEFR according to the criteria proposed by ETS (2023).

Self-Regulation

Four types of self-regulation from Tseng et al. (2017) were adopted for the current study: boredom control, awareness control, goal control, and emotion control (5 items for each control). Boredom control refers to the control used to reduce learners’ negative emotional states that interfere with strategy use, and an example item is “When I studied English in the past, I often gave up half-way during the learning process” (Tseng et al., 2017, p. 538). Awareness control is defined as the ability to assess the likelihood and monitor the occurrence of internal and external distractions; e.g., “When learning English, I think my methods of controlling my concentration are effective” (Tseng et al., 2017, p. 538). Goal control is the active tendency to take the initiative to achieve learning goals, and an example item is “When learning English, I believe I can achieve my goals more quickly than expected” (Tseng et al., 2017, p. 537). Emotion control refers to the ability to control learners’ affective aspects in language learning; e.g., “When feeling bored with learning English, I know how to regulate my mood in order to invigorate the learning process” (Tseng et al., 2017, p. 537). All self-regulation items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true). Because the awareness, goal, and emotion control items measured the positive side of self-regulation, but only the boredom control items seemed to reflect the opposite side of self-regulation (i.e., reverse items), these items were inverted when analyzing the data.

Grit

To measure learners’ grit, Teimouri et al.’s (2022) L2 grit scale (9 items) was used. Teimouri et al.’s grit scale is divided into two subcategories, including effort (5 items) and interest (4 items), and the total scores of these two subcategories were used in this research. Grit refers to persistence and passion for long-term and higher-order goals in L2 learning, and an example item is “I put much time and effort into improving my English language weaknesses” (Teimouri et al., 2022, p. 615). As with the self-regulation scale, this variable was measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true).

Motivational Variables

The three motivational variables or motivational beliefs, including self-efficacy, intrinsic values, and growth mindset, were used in the present study. To measure self-efficacy and intrinsic values, Pintrich and De Groot’s (1990) Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) was used (9 items for each). Since the items from the MSLQ are contextualized in the classroom setting, we measured the two motivational variables in the context of an English class in which the data were collected. Self-efficacy refers to the learner’s confidence regarding performance and achievement in the English class; e.g., “Compared with other students in this class I expect to do well” (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990, p. 40). Intrinsic value also refers to the learner’s intrinsic value for learning in the English class, and an example is “I think I will be able to use what I learn in this class in other classes” (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990, p. 40). These two motivational variables were also measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true). To measure growth mindset, the current study used the Language Mindset Inventory developed by Khajavy et al. (2020), which consists of eight items. Growth mindset refers to the belief that one’s intelligence regarding L2 learning is malleable and can grow with effort, and an example is “No matter who you are, you can significantly change your language intelligence level” (taken from the supplemental material of Khajavy et al., 2020). This variable was measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Data Collection

The current study took place in three English classes. Data collection was conducted from January 15 to January 22, 2024. Since the three English classes were taught by three different English teachers, they followed the same procedure each time. First, the teachers explained the purpose and voluntary nature of participating in this study to the students, and the students chose whether or not they agreed to participate in this research. Then, the students answered all the questions in the questionnaire created by Google Form, which took about 10 minutes. Since some of the students were absent on the day of this research, they were asked to answer the questionnaire in the next class.

Regarding the TOEFL scores, since the students in this study took the test at the end of January 2024, the TOEFL scores obtained from this administration were used in the current research. For students who were absent on the test day, their most recent prior TOEFL scores were used instead.

Data Analyses

All the data obtained in our research was analyzed using JASP, an open-source statistical software. In our research, we used a correlation analysis with Bayesian estimation in which we examined the magnitude of the relationship between variables and the probability of whether the results support a null hypothesis (BF01) [H0: ρ = 0] (i.e., no correlation between variables) or an alternative hypothesis (BF10) [H1: ρ ≠ 0] (i.e., a correlation between variables). The decision to use Bayesian estimation is that since our research could not include a sufficient number of data, it was anticipated that updating the results by adding more data would be worthwhile in future studies. Since Bayesian statistics allows us to add additional data and update the results, it was thought to be more beneficial to use Bayesian estimation compared to frequentist analyses in this research. It should also be noted that our research used Kendall’s tau (τ) instead of Pearson’s rho (r) in the correlation analysis. This was based on the assumption that the data for some of the variables did not follow a normal distribution, which was checked before the analysis was performed. For the prior distribution of ρ, a beta distribution β (1, 1), which is the default in JASP, was used. The Bayes factor (BF) or posterior distribution was interpreted using the following criteria: * BF10 > 10 = strong; ** BF10 > 30 = very strong; and *** BF10 > 100 = decisive (Goss-Sampson et al., 2020).

Results

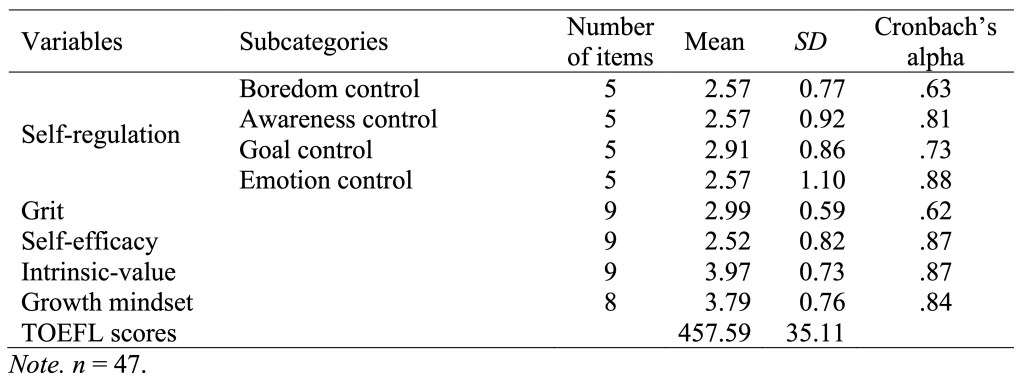

Descriptive Statistics and Cronbach’s Alpha for Variables

Table 1 shows the results of the descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each variable in the current study. As can be seen from Table 1, motivational variables such as intrinsic value (M = 3.97, SD = 0.73) and growth mindset (M = 3.79, SD = 0.76) showed relatively higher means compared to other variables. This result is not surprising, possibly because the students in this study were studying in an English-related department; thus, they were more likely to recognize the value of learning English and the high possibility of improving their English proficiency through effort.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics and Cronbach’s Alpha for Each Variable

Regarding the reliability of each variable, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, while most of the variables met satisfactory conditions, grit and boredom control in self-regulation appeared to have relatively lower coefficients. However, since the current research used a relatively small sample size, and based on Dörnyei and Taguchi’s (2010) benchmark, we decided to include all data in the final analyses.

Correlations Between Self-Regulation, Grit, Motivational Variables, and TOEFL Scores

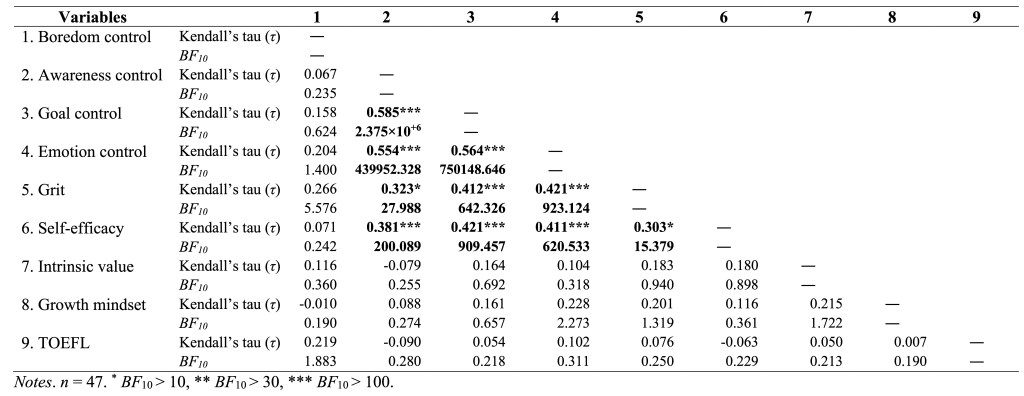

To answer the first and second research questions, we conducted Kendall’s tau correlation analysis using Bayesian estimation. Table 2 shows the calculated Kendall’s tau correlation coefficients (τ) between self-regulation, grit, motivational factors (i.e., self-efficacy, intrinsic value, and growth mindset), and TOEFL scores. Regarding the first

Table 2

Results of Bayesian Kendall’s Tau (τ) Correlation Analysis

research question about the relationship between the SRL variables and TOEFL scores, the results showed that all values of BF10 for the correlation coefficients between the SRL variables and TOEFL scores were less than 10, indicating that the SRL variables were unlikely to correlate with TOEFL scores.

With regard to the second research question about the relationships between self-regulation, grit, and the three motivational variables, the results showed that some of the subcategories of self-regulation, such as awareness, goal, and emotion control, were positively correlated with grit (τ = .32–.42, BF10 > 10–100) and self-efficacy (τ = .38–.42, BF10 > 100) with strong Bayesian posterior support. Additionally, grit was positively correlated with self-efficacy, also with strong Bayesian posterior support (τ = .30, BF10 > 10). Although the causality between the variables must be interpreted with caution, self-regulation skills may promote students’ grit and self-efficacy, and vice versa. Meanwhile, a lack of correlations was found between intrinsic value or growth mindset and most of the other variables. Overall, therefore, contrary to our initial assumption, our results tended to support the null hypothesis, suggesting a lack of correlations between many of the variables.

Discussion

Correlations between Self-Regulation, Grit, Motivational Variables, and TOEFL Scores

In response to the two research questions, our research examined the correlations (τ) between self-regulation, grit, the three motivational variables (i.e., self-efficacy, intrinsic value, and growth mindset), and TOEFL scores among Japanese EFL university students. While the results of Bayesian Kendall’s tau correlation analysis found no significant correlations between SRL variables and TOEFL scores (RQ1), some subcategories of self-regulation showed moderate correlations with grit and self-efficacy (RQ2). However, other variables, such as intrinsic value and growth mindset, did not exhibit significant correlations with most of the other variables based on the posterior distribution of the Bayesian estimation (RQ2). Therefore, these results supported the null hypothesis, indicating that stronger correlations between the variables were not confirmed.

The substantial influence of self-regulation on grit and self-efficacy, or vice versa, is consistent with previous research on students from different contexts (e.g., Bai & Guo, 2018; Bai & Wang, 2021; Guo et al., 2023). According to self-regulation theory, learners’ level of self-regulation is closely related to their motivation to learn a subject, making them more resilient to competing motivations, distractions, and procrastination (Pintrich, 1999; Tseng et al., 2017). Recent SRL studies have also shown that self-regulation is influenced by motivational variables such as self-efficacy (Bai & Wang, 2021) and grit (Guo et al., 2023). Thus, our findings support self-regulation theory and evidence from previous SRL studies that self-regulation, grit, and self-efficacy are interrelated. Given that most Japanese EFL learners have limited opportunities to use English in their daily lives, this interrelationship is particularly noteworthy. It suggests that fostering self-regulation skills, grit, and self-efficacy may be essential for strengthening learners’ SRL in English learning. As SRL is regarded as one of the most influential learning theories, where learners actively engage in their own learning through regulation, motivation, and strategic action, these variables likely reinforce one another and contribute to the promotion of autonomous learning. They may also serve as foundational elements in developing self-access learning skills.

The absence of correlations between intrinsic value or growth mindset and any of the other variables may be due to the unique English learning environment of the target students. As mentioned earlier, the participants in this study specialized in English-related studies. The descriptive statistics calculated indicated higher mean scores for intrinsic value and growth mindset compared to other variables among the students. In essence, irrespective of the level of self-regulation and English proficiency, the majority of students showed a higher interest in learning English and embraced the idea of potentially improving their second language through effort. These tendencies may have led to the lack of correlations between these two motivational factors and other variables among the students.

Additionally, a lack of correlations was found between TOEFL scores and any of the other variables. This finding contrasts with previous studies that have reported positive associations between English proficiency or achievement and SRL variables (e.g., Bai & Guo, 2021; Guo et al., 2023). There are several possible explanations for this discrepancy across studies. One possible explanation is related to the learning environment in which students are placed. Many SRL studies in L2 have been conducted in specific nations such as Hong Kong (e.g., Bai & Guo, 2021; Bai & Wang, 2023; Guo et al., 2023). However, as highlighted by Bai and Wang (2021), beliefs and motivations are shaped by cultural values, social norms, learning environments, and educational systems. For example, Japanese learners may exhibit relatively higher or lower levels of motivation regardless of their English proficiency, in contrast to learners in Hong Kong. These motivational tendencies may be influenced by how learners are encouraged to study English, the societal expectations surrounding English proficiency in Japan, the structure of English language education, and the context in which English is learned. Consequently, the affective SRL variables examined in our study may not have been directly related to the English proficiency of Japanese university students, unlike findings reported in studies involving Hong Kong learners.

Moreover, the specific learning environment of our participants—the students at the university possibly preparing to study abroad—may have introduced external motivational factors not captured by our SRL measures. The pressure to improve English levels and the prospect of studying abroad could have overshadowed the influence of internal SRL factors on English proficiency. This suggests that even among Japanese learners, variations in results may arise due to factors such as their academic department.

Another reason may be related to the specific skills targeted by SRL studies. While our research used the TOEFL test, including reading, grammar, and listening, to determine students’ English proficiency and examined its relationships with SRL variables, the majority of previous SRL studies found a strong association of SRL variables with English proficiency or achievement, such as vocabulary and writing (e.g., Bai & Guo, 2021; Bai & Wang, 2021; M. F. Teng et al., 2024; Tseng & Schmitt, 2008). Accordingly, these differences may account for the variation in the relationship between SRL variables and English proficiency across studies.

The direct or indirect association of SRL variables with L2 learning may be another possible reason. While learners’ behavior (i.e., use of learning strategy) may be directly related to processing information and storing the target L2, learners’ self-regulation, grit, and affective variables may be indirectly related to L2 learning, such as enhancing and maintaining L2 learning behavior, and controlling and managing the learning process, rather than having a direct association with L2 learning outcomes. Thus, the indirect role of self-regulation, grit, and motivation in L2 learning may have resulted in the absence of significant associations with English proficiency in this research.

Conclusion

The current research examined the relationship between self-regulation, grit, motivational variables (i.e., self-efficacy, intrinsic value, and growth mindset), and English proficiency (i.e., TOEFL scores) among Japanese university students. The results of the Bayesian Kendall’s tau correlation analysis showed that some self-regulation (i.e., awareness, goal, and emotion control) was strongly correlated with grit and self-efficacy, but no correlations were found between most of the variables, which is inconsistent with previous SRL studies in L2 with students from different countries (e.g., Bai & Guo, 2021; Bai & Wang, 2023; Guo et al., 2023). While the inconsistent results across different learning contexts are an important finding of this research, it is worth noting that our study included a relatively small number of participants. Thus, our future research should include more data, update the results, and investigate how different learning environments affect the SRL process in L2. In addition, as this study primarily focused on examining the relationships among SRL-related variables and English proficiency, we did not thoroughly explore the reasons behind the current findings. Since qualitative data may offer valuable insights into the discrepancies observed between previous studies and the present results, this aspect warrants further investigation through qualitative methods in future research. Furthermore, although our study used TOEFL scores, which primarily assess receptive skills such as listening, reading, and grammar usage, it did not include measures of productive skills such as writing and speaking. Since SRL variables measured in this study may also influence these unmeasured skills, future research should expand its focus to include a broader range of language skills, particularly productive ones. This would allow for a more comprehensive evaluation of how SRL relates to various aspects of L2 proficiency.

Based on these findings, we propose future directions for L2 SRL research. First, more studies with students from diverse learning environments are needed. While previous L2 SRL studies have mainly focused on learners from Hong Kong and China, our study targeted university students in Japan. Although we found some differences compared to earlier studies conducted in Hong Kong and China, it is important to note that our study was conducted with students enrolled in an English-related major at the university. Due to such a specific learning environment, the students in our study may have produced relatively higher means for intrinsic value and growth mindset regardless of their proficiency level, which may be related to the lack of correlations between some of the SRL variables. Because similar results may not be obtained from students in non-English departments, studies targeting students in more diverse environments are needed to verify the effects of such environments on L2 SRL.

Second, while our research used correlation analysis to examine relationships between variables, future studies would benefit from more advanced statistical techniques such as regression analysis and SEM. These methods can provide deeper insights into the causal relationships between SRL variables and L2 proficiency, offering a more comprehensive understanding of how these factors interact in the L2 learning process. Such analyses could inform more targeted approaches to promoting SRL in L2 teaching and learning contexts.

Finally, our research adopted a cross-sectional research design, in which we examined how the SRL variables related to English proficiency. However, to gain a deeper understanding of how the learners’ SRL process relates to L2 proficiency, longitudinal research would be beneficial to see how SRL is related to L2 learning and how the SRL variables measured after longitudinal intervention can predict L2 proficiency. This approach allows us to better understand the nature of the SRL process and its role in L2 learning. Therefore, future studies in this direction would be valuable.

Note

Owing to a request by the participants involved in this study, the data utilized cannot be provided for open use.

Notes on the Contributors

Shotaro Ueno is a lecturer at the Academic Success Center, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan. He is also a Ph.D. student at the Graduate School of Foreign Language Education and Research, Kansai University, Japan. His current research interests include language learning strategies, self-regulated learning, L2 motivation, and secondary research such as systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Siwon Park is a professor in the Faculty of International Liberal Arts at Juntendo University, Japan. His research interests currently focus on educational assessment, learning theories, intercultural communication, critical thinking, resilience, and other learner characteristics in L2 learning, as well as research methodology.

References

Bai, B., & Guo, W. (2018). Influences of self-regulated learning strategy use on self-efficacy in primary school students’ English writing in Hong Kong. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 34(6), 523–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2018.1499058

Bai, B., & Guo, W. (2021). Motivation and self-regulated strategy use: Relationships to primary school students’ English writing in Hong Kong. Language Teaching Research, 25(3), 378–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168819859921

Bai, B., & Wang, J. (2021). Hong Kong secondary students’ self-regulated learning strategy use and English writing: Influences of motivational beliefs. System, 96, 102404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102404

Bai, B., & Wang, J. (2023). The role of growth mindset, self-efficacy and intrinsic value in self-regulated learning and English language learning achievements. Language Teaching Research, 27(1), 207–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820933190

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Dörnyei, Z., & Taguchi, T. (2010). Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration and processing(2nd ed.). Routledge.

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

Dweck, C. S. (1999). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Taylor & Francis.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618804166

Eccles, J. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motives (pp. 75–146). Freeman.

Educational Testing Service (ETS). (2023). The TOEFL ITP® Assessment Series. https://www.ets.org/toefl/itp/scoring.html#accordion-d5f026058d-item-bca03d239f (accessed 28 October 2024).

Fathi, J., Pawlak, M., Saeedian, S., & Ghaderi, A. (2024). Exploring factors affecting foreign language achievement: The role of growth mindset, self-efficacy, and L2 grit. Language Teaching Research, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688241227603

Graham, G., Woore, R., Porter, A., Courtney, L., & Savory, C. (2020). Navigating the challenges of L2 reading: Self-efficacy, self-regulatory reading strategies, and learner profiles. The Modern Language Journal, 104(4), 693–714. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12670

Goss-Sampson, M. A., van Doorn J., & Wagenmakers, E. J. (2020). Bayesian inference in JASP: A guideline for students. https://jasp-stats.org/resources/

Guo, W., Bai, B., Zang, F., Wang, T., & Song, H. (2023). Influences of motivation and grit on students’ self-regulated learning and English learning achievement: A comparison between male and female students. System, 114, 103018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2023.103018

Keegan, K. (2017). Identifying and building grit in language learners. English Teaching Forum, 55, 2–9.

Khajavy, G. H., MacIntyre, P. D., & Hariri, J. (2020). A closer look at grit and language mindset as predictors of foreign language achievement. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 43(2), 379–402. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263120000480

Lake, J. (2013). Positive L2 self: Linking positive psychology with L2 motivation. In T. Apple, D. Da Silva, & T. Fellner (Eds.), Language learning motivation in Japan (pp. 225–244). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783090518-015

Liem, A. D., Lau, S., & Nie, Y. (2008). The role of self-efficacy, task value, and achievement goals in predicting learning strategies, task disengagement, peer relationship, and achievement outcome. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 33, 486–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2007.08.001

Lou, N. M., Chaffee, K. E., & Noels, K. A. (2022). Growth, fixed, and mixed mindsets: Mindset system profiles in foreign language learners and their role in engagement and achievement. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 44, 607–632. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263121000401

MacIntyre, P. D., & Khajavy, G. H. (2021). Grit in second language learning and teaching: Introduction to the special issue. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning, 3(2), 1–6. https://mail.jpll.org/index.php/journal/article/view/86

Macnamara, B. N., & Burgoyne, A. P. (2023). Do growth mindset interventions impact students’ academic achievement? A systematic review and meta-analysis with recommendations for best practices. Psychological Bulletin, 149(3–4), 133–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000352

Papi, M., Wolf, D., Nakatsukasa, K., & Bellwoar, E. (2021). Motivational factors underlying learner preferences for corrective feedback: Language mindsets and achievement goals. Language Teaching Research, 25(6), 858–877. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211018808

Park, S., Ueno, S., & Sugita, M. (2025). The impact of resilience and self-regulation on L2 proficiency among ESL learners. International Journal of TESOL Studies, 7(1), 105–125. https://doi.org/10.58304/ijts.20250107

Pawlak, M., Csizér, K., Kruk, M., & Zawodniak, J. (2022). Investigating grit in second language learning: The role of individual difference factors and background variables. Language Teaching Research, 29(5), 2093–2118. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221105775

Pintrich, P. R. (1989). The dynamic interplay of student motivation and cognition in the college classroom. In C. Ames & M. Maehr (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement: Vol. 6. Motivation enhancing environments (pp. 117–160). JAI Press.

Pintrich, P. R. (1999). The role of motivation in promoting and sustaining self-regulated learning. International Journal of Educational Research, 31, 459–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(99)00015-4

Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology 82(1), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.33

Plonsky, L., & Oswald, F. L. (2014). How big is “big”? Interpreting effect sizes in L2 research. Language Learning, 64(4), 878–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12079

Schunk, D. H., & Greene, J. A. (2018). Historical, contemporary, and future perspectives on self-regulated learning and performance. In D. H. Schunk & J. A. Greene (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (2nd ed.) (pp. 1–15). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315697048-1

Takeuchi, O., Griffiths, C., & Coyle, D. (2007). Applying strategies to contexts: The role of individual, situational, and group differences. In A. Cohen & E. Macaro (Eds.), Language learner strategies: Thirty years of research and practice (pp. 69–92). Oxford University Press.

Teimouri, Y., Plonsky, L., & Tabandeh, F. (2022). L2 grit: Passion and perseverance for second-language learning. Language Teaching Research, 26(5), 893–918. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820921895

Teng, L. S., & Zhang, L. J. (2016). A questionnaire-based validation of multidimensional models of self-regulated learning strategies. The Modern Language Journal, 100(3), 674–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12339

Teng, M. F., Mizumoto, A., & Takeuchi, O. (2024). Understanding growth mindset, self-regulated vocabulary learning, and vocabulary knowledge. System, 122, 103255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2024.103255

Tseng, W. T., Dörnyei, Z., & Schmitt, N. (2006). A new approach to assessing strategic learning: The case of self-regulation in vocabulary acquisition. Applied Linguistics, 27(1), 78–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ami046

Tseng, W. T., Liu, H., & Nix, J. M. L. (2017). Self-regulation in language learning: Scale validation and gender effects. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 124(2), 531–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031512516684293

Tseng, W. T., & Schmitt, N. (2008). Toward a model of self-regulated vocabulary learning: A structural equation modeling approach. Language Learning, 58(2), 357–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2008.00444.x

Ueno, S., & Takeuchi, O. (2022). Self-regulated vocabulary learning in a Japanese high school EFL environment: A structural equation modeling approach. JACET Journal, 66, 97–111. https://doi.org/10.32234/jacetjournal.66.0_97

Ueno, S., Takeuchi, O., & Shinhara, Y. (2025). Exploring the studies of self-regulated learning in second/foreign language learning: A systematic review. International Journal of TESOL Studies, 7(1), 126–147. https://doi.org/10.58304/ijts.20250108

Wolters, C. A., & Hussain, M. (2015). Investigating grit and its relations with college students’ self-regulated learning and academic achievement. Metacognition and Learning, 10(3), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-014-9128-9

Xu, J., & Wang, Y. (2022). The differential mediating roles of ideal and ought-to L2 writing selves between growth mindsets and self-regulated writing strategies. System, 110, 102900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2022.102900

Zhao, P., Zhu, X., Yao, Y., & Liao, X. (2023). Ideal L2 self, enjoyment, and strategy use in L2 integrated writing: A self-regulatory learning perspective. System, 115, 103033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2023.103033

Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (2011). Self-regulated learning and performance: An introduction and an overview. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. J. Schunk (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulated learning and performance (pp. 1–12). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203839010