Badli Esham Ahmad, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3806-729X

Zuria Akmal Saad, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia

Azwan Shah Aminuddin, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia

Mohd Amli Abdullah, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0320-8582

Ahmad, B. E., Saad, Z. A., Aminuddin, A. S., & Abdullah, M. A (2023). Self-directed learning of Malay undergraduate students. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(3), 244–266. https://doi.org/10.37237/140302

Abstract

This study investigated the self-directed learning readiness (SDLR) of 944 Malay undergraduate students in a Malaysian university, using Guglielmino’s Self-directed Learning Readiness Survey (1977), which is a 58-item Likert scale questionnaire that uses the Delphi technique to identify the level of SDLR of adult learners. Results indicate that the majority of the participants possess a moderate readiness level. The age-based analysis, though less relevant due to a predominantly young demographic, still indicates a need for facilitation in their learning journeys. These findings underscore the importance of tailored strategies and support mechanisms (i.e., guidance from instructors) to enhance educational outcomes.

Keywords: Self-directed learning, online learning, Malay ethnicity, learning environments, gender-specific interventions

Research on self-directed learning (SDL) was abundant at the turn of the 20th century as the growth of the internet has opened up new areas of investigation (Brookfield, 2009). E-learning involves using the internet to access education and information, disregarding limitations of time and location (Al-Adwan et al., 2022). The shift to online learning has brought SDL to the forefront, its context has been altered by technology (Li et al., 2021), and it is considered crucial for the success of online education (Zhu, 2021). With online learning becoming the norm globally, especially with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, learners are expected to take more responsibility for their own education and have more student learning time (SLT). In our contemporary society, characterized by swift social and contextual changes, particularly in the digital era, the ability to engage in self-directed learning stands as an essential skill for adults (Morris & König, 2020). Therefore, being prepared for SDL is essential for learners to succeed in the digital age. With this in mind, the purpose of this paper is to investigate the level of self-directed learning readiness (SDLR) of young Malay learners in a public university, identify the level of SDL based on different programs, and also to determine if the age of the learners affects their SDLR as suggested by the literature.

Self-Directed Learning

The concept of SDL has roots in the mid-1800s (Brandt, 2020), but its scholarly study can be traced back to the 1960s with the publication of Cyril Houle’s book The Inquiring Mind. Houle’s view that individuals can learn alone, in groups, or in institutions helped clear the way for the term SDL. Allen Tough and Malcolm Knowles, two of Houle’s doctoral graduates, were also instrumental in shaping the field of SDL (Loeng, 2020). Tough concluded that adults spend a significant amount of time on learning projects, while Knowles introduced andragogy and published a book on SDL. Eduard Lindeman was an early contributor to the field, who believed in the importance of self-direction in adult learning. In the 1980s, Candy observed that self-direction had become popular in the field of adult education (Loeng, 2020).

SDL is an educational approach where individuals take charge of their own learning by setting their own goals and choosing the resources and methods to achieve them. This approach values the learner’s autonomy and prior experiences and encourages them to be proactive in their own education. It has been widely researched and reported to be an effective method for fostering critical thinking, motivation, and personal growth. For example, a study by Tough (1971) found that self-directed learners had higher levels of achievement and satisfaction compared to those in traditional educational settings. Another study by Knowles (1975) identified six assumptions of SDL, including the need for experience, responsibility, self-direction, and self-evaluation. These findings highlight the importance of SDL in contemporary education and its potential to enhance personal and professional development.

SDL refers to the process in which individuals take the initiative and responsibility for their own learning, with or without the help of others. It involves diagnosing learning needs, setting goals, finding resources, choosing strategies, and evaluating outcomes. According to Knowles (1975), SDL is based on the principles of andragogy, which assumes a shift in the learner’s self-concept from dependent to self-directed, whereas teacher-directed learning (pedagogy) is based on the teacher being responsible for learning outcomes. The concept of SDL emerged in the mid-twentieth century as a way to differentiate adult education from childhood education and general learning (Loeng, 2020). However, SDL is a multifaceted concept, and different researchers have different perspectives on it. Some emphasize the importance of personal control over planning and management, while others stress the interdependent and collaborative aspects of SDL. According to Garrison (1997), SDL should be seen as a collaborative constructivist approach, where the learner takes responsibility for constructing meaning with the help of others.

The concept of SDL has been defined and classified by different authors into various dimensions. Candy (1991) has two dimensions of SDL, one of control within an institutional setting and the other of learner control outside of institutional settings. Brockett and Hiemstra (1991) also have two dimensions of SDL, personal responsibility in the teaching-learning process and personal responsibility in one’s own thoughts and actions. Other authors have defined SDL as a central tenet of learners being responsible for their own learning process. Long (1990) identifies three dimensions of SDL: sociological, pedagogical, and psychological. The sociological dimension focuses on social isolation, the pedagogical dimension on freedom in determining learning goals, and the psychological dimension on the personal characteristics of the learner and their control over the learning process. Long (1990) argues that much of the discussion on the dimensions of SDL has focused on sociological and pedagogical factors and that the psychological dimension is generally ignored (Long, 1990 cited in Loeng, 2020).

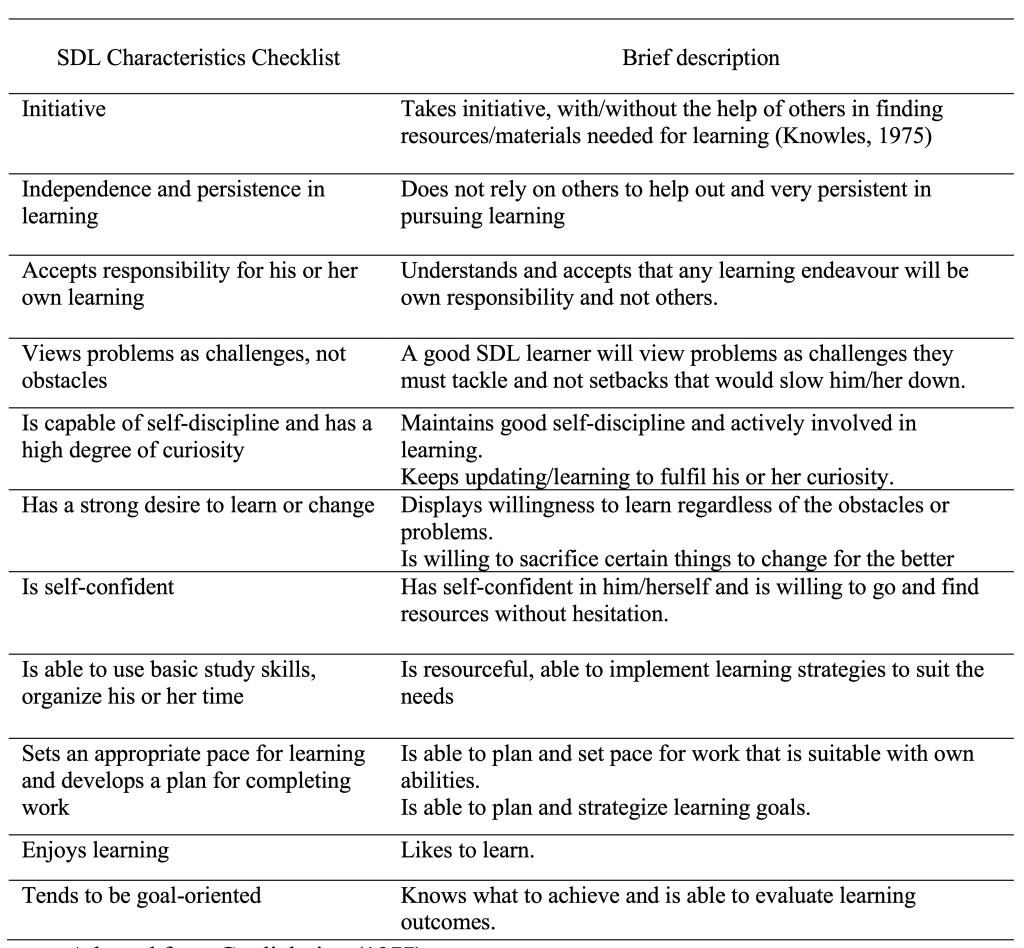

According to Guglielmino (1977), a self-directed learner is someone who takes charge of their own learning, is independent and determined, takes responsibility for their education, views challenges as opportunities, and is curious, self-disciplined, and self-assured. They have a strong desire to learn or change, are skilled in basic study techniques, can manage their time and set a learning pace, have a plan to complete work, and are goal-oriented with a love for learning.

The characteristics of highly self-directed learner can be summarized in Table 1 based on the characteristics proposed by Guglielmino (1977).

Table 1

Summary Of SDL Characteristics Proposed by Guglielmino (1977)

Source: Adapted from Guglielmino (1977)

Factors Studied Related to SDL

Past studies have explored the relationship between SDLR and various factors in different learning environments. A study by Wijaya and Khoiriyah (2021) found a majority (87%) of first-year medical students displayed high levels of SDLR but no significant relationship between SDL and online learning preferences. However, their study of medical students concurred with Heo and Han (2018) who stated first-year medical students would normally have high SDLR because they have lower stress levels. Their study found that SDL has a significant relationship with motivation and academic stress but not with age.

Motivation and stress levels are good predictors of SDLR among online learners. Another study (Al-Adwan et al., 2022) found that SDL is a necessary skill for the success and satisfaction of online learning. Laine et al. (2021b) found that post-graduate adult learners had high levels of SDL and concluded that maturity plays a role in self-directedness. Zhu (2021) suggests developing self-management skills to aid in SDL. Li et al. (2021) found that learners with high levels of SDL were more engaged in reading and motivated in their language studies. Studies have shown that SDL is important for online learning success and satisfaction and that maturity plays a role in developing SDL.

Lai (2015) found a positive relationship between SDL and technology acceptance (perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use). In Lai’s study, the results showed that affection support, capacity support, and behavior support from teachers all positively influenced students’ self-directed use of technology for language learning outside the classroom, and the final model explained 22% of the variation in learners’ self-directed use.

Numerous other studies (e.g., Lesfato, 2020; Nobaew, 2021; Razali et al., 2018) have identified a relationship between SDLR and learning performance and indicate that SDLR is an important factor in success and satisfaction. We have seen from these studies that learners benefit from support, awareness-raising about learning, and teacher-led instruction on learning strategies.

Studies on SDL in Malaysia

SDL is an important aspect of lifelong learning and has gained attention in the context of higher education in Malaysia. Several studies have been conducted to explore the relationship between SDL and various factors, such as social networking sites (SNS), learning strategies, and guided learning approaches. One study by Salleh et al. (2019) investigated the relationship between SDL, SNS, and lifelong learning among master’s and Ph.D. students in Malaysia. The study found that there is a significant relationship between SDL and SNS, suggesting that the use of SNS can enhance SDL and contribute to lifelong learning.

Another study by Puteh et al. (2022) focused on postgraduate students in one of the largest public universities in Malaysia. The study examined different learning strategies, including cognitive, metacognitive, and self-regulation strategies, and identified the most useful strategies for postgraduate students. The findings of this study can inform curriculum and learning approaches in higher education, particularly for adult learners.

In the context of first-year university students in Malaysia, Hutasuhut et al. (2023) conducted a study to investigate the efficacy of a guided learning approach in promoting self-directedness. The study used the SECI Model as a theoretical framework and found that the guided learning approach had a positive impact on students’ self-directedness. The results showed that the majority of participants exhibited an increase in their SDL level after the implementation of the guided learning approach. These findings highlight the importance of fostering SDL in higher education, particularly among first-year university students. It is crucial for students to develop the skills necessary for SDL, as they are expected to study independently and take responsibility for their own learning. The guided learning approach can be an effective strategy to promote self-directedness and enhance the learning experience for students.

One study by Allam et al. (2020) focused on online distance learning readiness during the COVID-19 outbreak among undergraduate students in Malaysia. The study examined the level of computer/internet literacy competency (CIL), SDL, and motivation for learning (MOL) among students. The findings indicated a high level of CIL, while SDL and MOL were reported at a lower level. This study provides insights into the readiness of Malaysian undergraduate students for online distance learning.

In addition, Menon (2023) conducted a study on the implementation and assessment of SDL in the pre-clinical medical school curriculum in Malaysia. The study aimed to assess student satisfaction and content mastery after implementing two novel models of SDL. The findings of this study can inform the incorporation of SDL into medical education and address the challenges associated with its implementation.

By this, SDL is a significant aspect of lifelong learning in Malaysia, influenced by factors like social networking sites, learning strategies, and guided learning approaches. It is crucial for educators and institutions to recognize the importance of fostering SDL and implement strategies to support students in developing this skill, enabling them to become more independent and take ownership of their learning journey. These studies, which encompass readiness for SDL among Malaysian undergraduate students, the efficacy of guided learning approaches, the implementation of SDL in medical education, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on SDL, collectively offer valuable insights for educators and institutions in Malaysia, helping them enhance SDL practices and adapt to changing learning environments.

Significance of the Study

The goal of this study is to investigate the SDLR of Malay undergraduate students. The significance of SDL research that focuses on one race in Malaysia is an important area of study that has received limited attention. While there is a wealth of research on SDL in general, there is a need for more specific investigations into how SDL is influenced by cultural and racial factors in Malaysia. Understanding the impact of race on SDL can provide valuable insights into designing effective educational interventions that cater to the diverse needs of students from different racial backgrounds. One study by Yin et al. (2022) highlights the importance of considering different races in Malaysia and the study suggests that different races in Malaysia have different behaviors and attitudes. This finding emphasizes the need for SDL study on the culture and race in the country. Research focusing on SDL among specific races holds significant importance for several reasons. Firstly, it allows for a deeper understanding of how cultural and racial factors influence the learning process and outcomes. Different racial and ethnic groups may have unique learning styles, preferences, and approaches to SDL. By examining SDL within specific racial groups, researchers can identify culturally relevant strategies and interventions that can enhance learning experiences and outcomes for individuals from those backgrounds Cobb et al. (2016). Secondly, SDL research that focuses on certain races can help uncover disparities and inequities in access to and engagement with SDL opportunities. It can shed light on the barriers and challenges faced by individuals from marginalized racial groups in accessing educational resources and developing SDL skills. This knowledge can inform the development of targeted interventions and support systems to address these disparities and promote equitable access to SDL opportunities (Wallace et al., 2021). Furthermore, SDL research that considers race can contribute to the development of culturally responsive pedagogies and instructional practices. It can help educators and institutions recognize the diverse learning needs and preferences of students from different racial backgrounds. By understanding how race intersects with SDL, educators can tailor instructional approaches, provide culturally relevant resources, and create inclusive learning environments that support the SDL journeys of all students (Shogren et al., 2018). Additionally, SDL research focusing on specific races can contribute to the broader understanding of racial disparities in educational outcomes. It can provide insights into how SDL skills and opportunities may vary across racial groups and how these differences may contribute to educational inequities. This knowledge can inform policy and practice aimed at reducing educational disparities and promoting educational equity for all students (Cheng et al., 2020). Lastly, SDL research that considers race can contribute to the development of a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the concept of race itself. It can challenge simplistic notions of race as a monolithic category and highlight the multidimensionality of racial identity and its influence on learning experiences. By examining the intersection of race and SDL, researchers can contribute to a more inclusive and culturally sensitive understanding of race in educational research and practice (Tejera, 2023). By this, SDL research that focuses on certain races is significant as it provides insights into the unique learning needs, challenges, and opportunities experienced by individuals from different racial backgrounds. It can inform the development of culturally responsive pedagogies, interventions to address disparities, and policies aimed at promoting educational equity. By considering race in SDL research, we can foster inclusive and equitable learning environments that support the SDL journeys of all students, regardless of their racial background.

The second significance is understanding the readiness of undergraduates in this context is crucial as it can provide valuable insights into their potential for SDL, which is becoming increasingly important in today’s rapidly changing educational landscape. Tertiary education is moving towards empowering learners where online learning and student learning time (SLT) are becoming a norm. The higher learning institution in which the study was conducted is heading in a similar direction. Hence, understanding the learner’s ability to be self-directed is pertinent to be able to formulate better learning experiences which would not hinder the learning process. Research focusing on SDL among undergraduate students holds significant significance for several reasons. Firstly, by understanding the factors that influence SDL among undergraduate students can help educators and institutions design effective learning environments and interventions to foster SDL skills (Zhang & Yang, 2023). Secondly, SDL research among undergraduate students can shed light on the impact of SDL on academic performance and learning outcomes (Tang et al., 2022). Furthermore, SDL research focusing on undergraduate students can contribute to the development of effective pedagogical approaches and instructional strategies (Hwang & Franklin, 2022; Tang et al., 2022). Additionally, SDL research among undergraduate students can help identify barriers and challenges to SDL and inform interventions to support students in developing SDL skills (Tang et al., 2022; Subekti, 2021). Moreover, SDL research among undergraduate students can contribute to the understanding of cultural and contextual factors that influence SDL. Different cultural backgrounds and educational contexts may shape students’ perceptions, attitudes, and approaches to SDL (Zhang & Yang, 2023; Subekti, 2021). SDL research focusing on undergraduate students is significant as it provides insights into the benefits of SDL, its impact on academic performance, and the factors that influence SDL among undergraduate students.

In addition, the findings may illuminate potential areas for support mechanisms, intervention in fostering SDL abilities, tailoring suitable instructional approaches, and eventually creating a more conducive environment for SDL among Malay undergraduate learners.

To achieve the study’s objectives, three key research questions have been formulated. The first question seeks to determine the SDL level among undergraduate students. The second question aims to explore whether there are any significant differences in SDL based on age among the undergraduates. The third question seeks to understand SDLR in different programs in the university.

Existing literature suggests that SDLR may vary across different age groups. Shogren et al. (2018) conducted a study exploring the impact of personal characteristics, including age and gender, on scores of the Self-Determination Inventory: Student Report (SDI:SR). The study found that older students generally express higher levels of self-determination, which aligns with the developmental nature of SDL. The study also established measurement invariance across different age cohorts and confirmed age-related differences, with younger participants showing lower levels of self-determination. Furthermore, Koçak et al. (2021) found in a large-scale study that there is an age-related increase in self-esteem, which can be linked to SDL. The study also found that males tend to have higher self-esteem than females. Research has shown that older students tend to display higher levels of SDLR compared to younger students. Early researchers on SDL focused on adult learners (Knowles, 1975, Guglielmino, 1977), and this would indicate a certain level of maturity among the learners where they would bring along more life experiences, and a greater sense of autonomy, which are conducive to SDL. On the other hand, younger students might still be transitioning from more structured learning environments, and their self-regulation skills and motivation may not be as developed. These findings suggest that age plays a significant role in SDL, with older individuals generally exhibiting higher levels of self-determination and self-esteem, which are key components of SDL. It is important to consider age as a factor when designing interventions and educational approaches to promote SDL among different age groups. Hence, the study intends to look at the level of readiness among young Malay learners.

Understanding SDLR in different programs in the university can build on previous research that focused on particular programs. Previous findings elsewhere show that SDLR varies among different programs in the university. A study by Premkumar et al. (2018) examined the SDLR of Indian medical students and found that culture and the type of prior schooling students had before entering medical college influenced SDLR. Another study by Sumuer (2018) emphasized that SDLR is regarded as both a prerequisite for and the outcome of lifelong learning, enabling individuals to take control of their learning. SDLR differs significantly among learners in different higher education programs, as specific attitudes, capabilities, and personality characteristics are required (Abdou et al., 2021). In the context of medical education, SDL is considered crucial for physicians to maintain lifelong learning and professional growth (Premkumar et al., 2018). SDLR among university students may vary based on factors field of study where Natural Sciences students were found to have different compared to students in Social and Health Sciences (Tekkol & Demirel, 2018).

Methodology

This quantitative study aims to identify the level of SDLR of Malay undergraduate students from a public university in Malaysia. The study employed a questionnaire as a data collection instrument. Specifically, Guglielmino’s SDLR Survey (SDLRS) (1977) was used, which is a 58-item Likert-scale questionnaire. The SDLRS was developed using the Delphi technique to identify the level of SDLR of adult learners.

The questionnaire was distributed to a total of 944 respondents who are new students who recently completed their secondary education and enrolled in the university. The collected data were then analyzed using statistical methods, including descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. The results of the analysis were used to draw conclusions and make recommendations for future research and practice.

The use of Guglielmino’s SDLRS is a widely accepted method of identifying SDLR (Laine et al., 2021b). The decision to use a quantitative approach and a questionnaire in this study was based on the need to obtain large amounts of data from a wide range of participants (Creswell, 2014). The use of inferential statistics in data analysis allowed for the examination of relationships between variables and the drawing of conclusions about the population based on the sample data (Gall et al., 2007).

Findings and Discussion

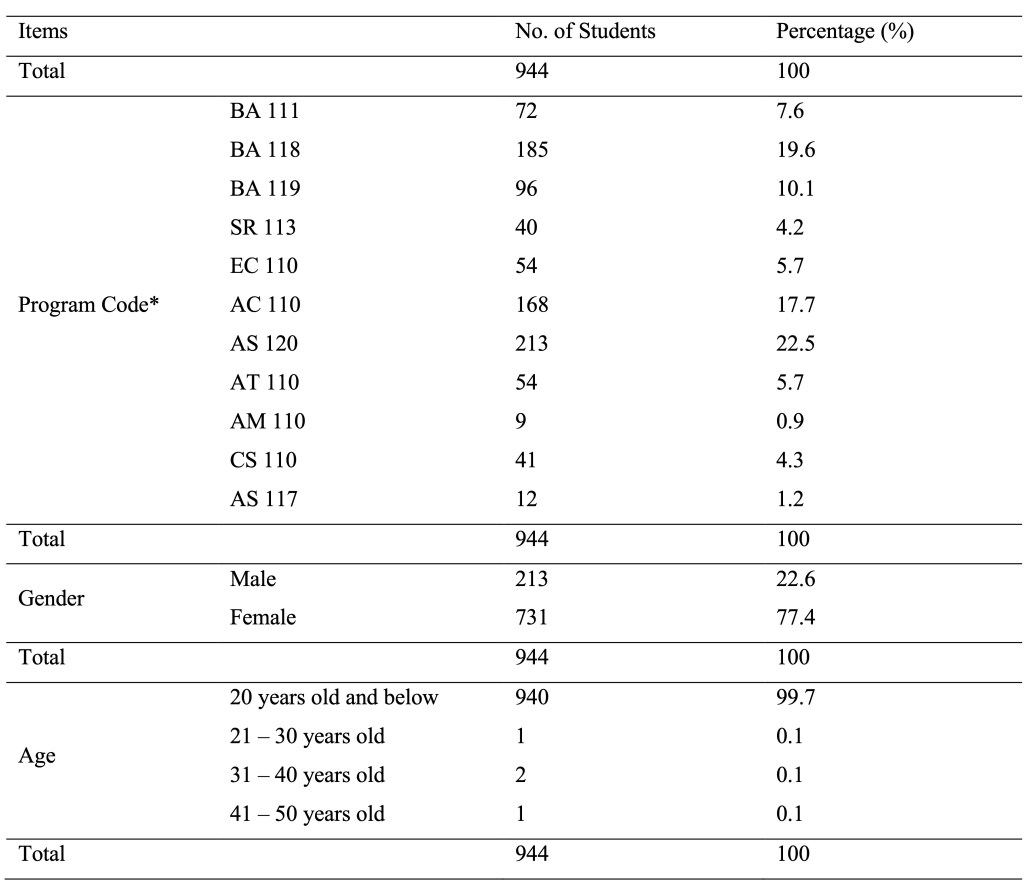

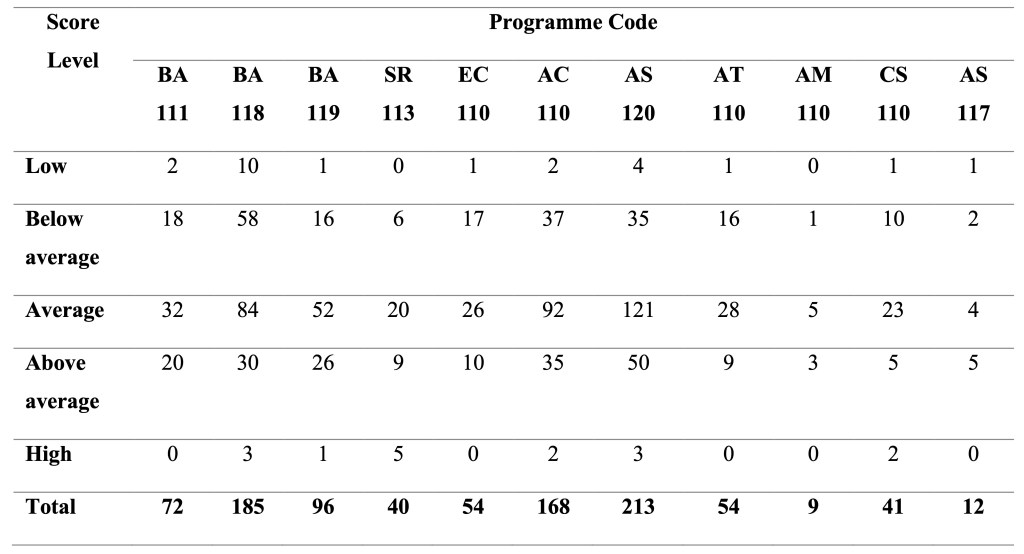

Table 2 displays the demographic information for this study. A total of 944 respondents were involved, and the highest number of respondents were from the AS120 (Science) program, followed by BA118 (Business) and AC110 (Accounting), with 213, 185, and 168 respondents, respectively. The number of respondents for other program codes was less than 100. There were 731 female respondents and 213 males, and the majority of them were below 21 years old, two of them were between 31 and 40 years old, and there was one respondent from each of the 21–30 years old and 41–50 years old ranges.

Table 2

Demographic Profiles

*Key

- AC 110 – Diploma in Accountancy

- AM 110 – Diploma Pentadbiran Awam (public administration)

- AS 117 – Diploma in Wood Industry

- AS 120 – Diploma in Science

- AT 110 – Diploma in Planting Industry Management

- BA 111 – Diploma in Business Studies

- BA 118 – Diploma in Office Management and Technology

- BA 119 – Diploma in Banking Studies

- CS 110 – Diploma in Computer Science

- EC 110 – Diploma in Civil Engineering

- SR 113 – Diploma in Sports Studies

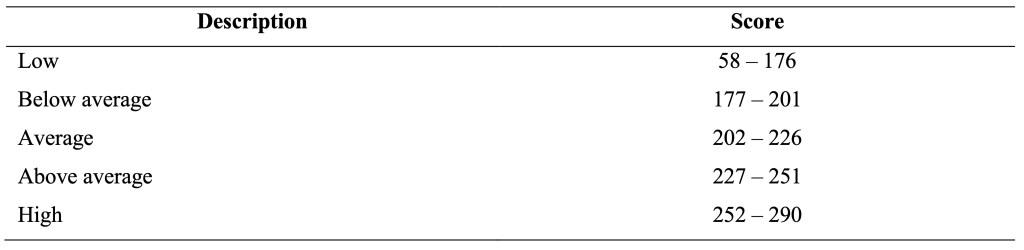

Scoring Ranges for the SDLR Scale

The SDLRS yields one total score ranging from 176 to 290 can be interpreted against a norm (Guglielmino, 1977). According to Beitler (2000) the average score for adults who complete the SDLRS is 214. Furthermore, Beitler (2000) provides the scoring range for adults on the SDLRS as shown in Table 3.

Table 3

Scoring Ranges for The SDLR Scale

Beitler (2000) interprets the scoring ranges stated in Table 3 as follows:

1. Persons with low or below average SDLRS scores usually prefer very structured learning options such as lectures in traditional classroom setting. Beitler (2000) refers to this as face-to-face classroom settings. A person with low or below-average SDLRS scores will require a large amount of time commitment from the facilitator.

2. People with average SDLRS scores are likely to be successful in more independent situations but are not fully comfortable with handling the entire process of identifying their learning needs, planning their learning, and then implementing their learning plans.

3. People with above-average or high SLDRS scores usually prefer to determine their own learning needs, plan their learning, and then implement their learning plans. They are better prepared to be self-directed and require minimum guidance.

The SDLRS scoring range stated above can be beneficial in determining the extent to which students can be classified in terms of those requiring guidance or not in their learning. Furthermore, the facilitator can determine where most of his or her time commitment when teaching can be directed. Beitler (2000) cautions, though, that people with above-average or higher SDLRS scores may choose structured learning, such as traditional courses or workshops, as part of their learning. Therefore, assuming that people with higher SDLRS scores do not require guidance in their learning might be an omission on the part of the facilitator, who might conclude that such learners do not require guidance based on their SDLRS scores. Nonetheless, a high SDLRS total score indicates a high level of readiness for SDL, and on the other end, a low SDLRS total score indicates a low level of readiness for SDL.

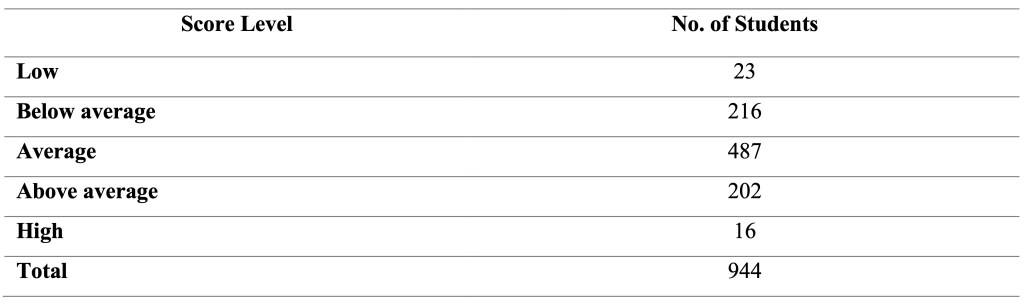

Table 4

Respondents’ SDLRS Scores

Table 4 indicates the SDLRS score of the respondents, and it can be seen that most students fall under the ‘Average’ category (51.5%). The ‘Low’ and ‘Below average’ categories, constitute 25% of the total number of students. As for the ‘Above average’ and ‘High’ categories, they make up23% of the total number of students. It can be concluded that the majority of students in the study are in the ‘Average’ category. This finding is similar to a study conducted by Ahmad and Majid (2010) on the SDLR of tertiary learners in Malaysia. However, such learners have the potential to be successful in more independent situations, but they are not fully comfortable with handling the entire process of identifying their learning needs, planning their learning, and implementing their learning plans (Beitler, 2000).

Table 5

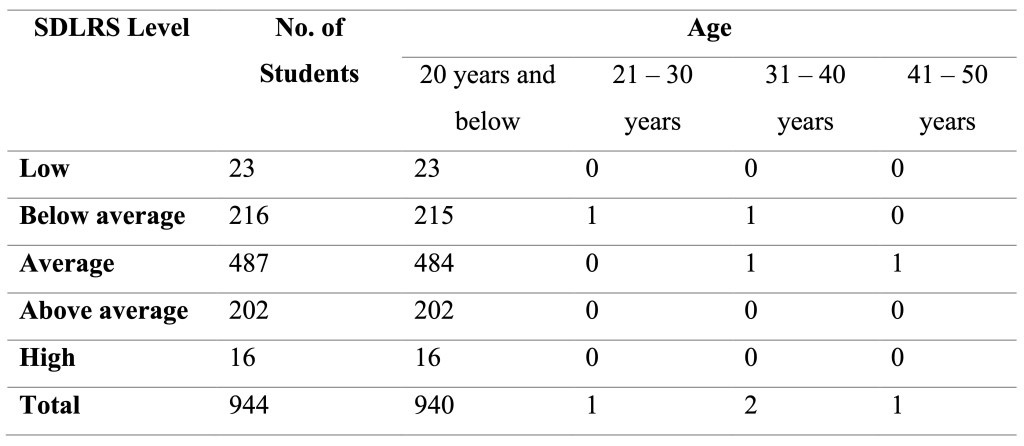

SDLRS Score Based on Age

Table 5 displays the SDLRS of respondents accordingly to their age. As there is only one student aged 21 to 30 years, two aged between 31 and 40 years, and only one aged between 41 to 50, performing a comparative analysis of SDL with the 99.58% of respondents aged under 20 was not appropriate. However, looking only at the respondents aged 20 years and below, it was found that 484 respondents out of the 944 of respondents claimed that they still need a facilitator to guide them, and are not fully ready for independent learning. The findings fall under what Beitler (2000) described as learners who need the guidance of an instructor without having the full confidence of managing their own learning. The findings in the study concur with Lai (2015) who states support from teachers can help to develop learners’ SDL. In addition, the findings also support the notion that age is another factor to consider in developing learners’ SDL (Laine et al., 2021a). The early researchers (Knowles (1975), Tough (1971), Garrison (1997), and Guglielmino (1977) often associated SDL with adult learners and the importance of taking control of one’s learning. This would suggest that maturity and age are pertinent factors in SDL. The respondents in the study are freshmen in a local university (eighteen years of age) and perhaps they may not have the ability and confidence to make decisions about their learning. In addition, they may not have been exposed to SDL in their secondary education prior to their entrance into the university. Furthermore, since the majority of the respondents are young adult learners, with either low, below average, or average levels of SDLR, the findings further strengthen the notion that age plays an important role in SDL. As such, intervention programs could be conducted (counseling, coaching, and advising) in order to develop the learners (Mitchell, 2023).

Table 6

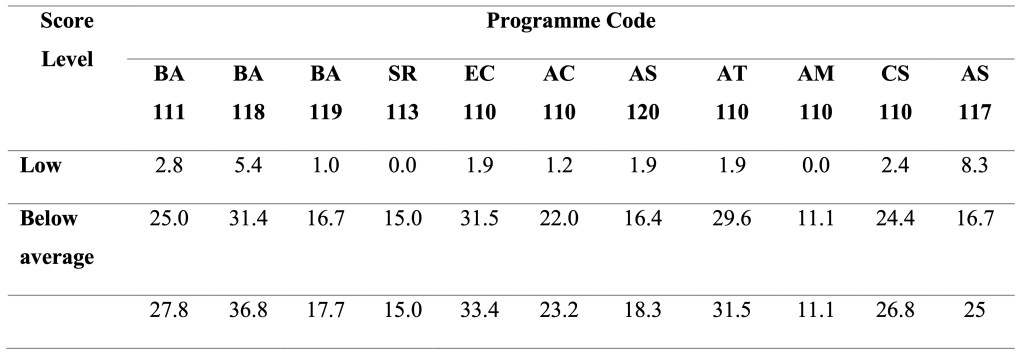

SDLRS Based on Programme Code

Table 6 displays the SDLR scores based on respondents’ program code. Table 7 shows the number of respondents with low or below-average SDLR scores in each program. The program scoring below the average is BA118 (Diploma in Office Management and Technology). Following closely is EC110 (Diploma in Civil Engineering), and AT110 (Diploma in Planting Industry Management) is in third place. These programs exhibit low or subpar scores on the SDLR Scale (SDLRS), and students in these courses typically gravitate towards highly structured learning modalities, such as conventional classroom lectures. Individuals falling into this category need substantial time and attention from the facilitator or instructor.

Table 7

SDLRS Lower and Below Average Score Based on Programme Code

This study sheds light on the SDLR of Malay students within the context of the study. The analysis of data reveals crucial insights into the distribution of SDLR among the respondents. Firstly, it indicates that a significant majority of Malay students fall within the ‘Average’ category, suggesting that they possess a moderate level of readiness for SDL. Meanwhile, the ‘Low’ and ‘Below average’ categories together comprise 25% of the total Malay student population, indicating a substantial portion of Malay students who may require additional support and guidance. Conversely, the ‘Above average’ and ‘High’ categories, constituting 23%, represent Malay students with a higher degree of SDLR. The age-based analysis, albeit less relevant due to the overwhelming representation of Malay students aged 20 years and below (99.58%), still highlights that a considerable number of these young learners express the need for facilitation in their learning journey, signifying room for improvement in fostering independence. The research demonstrates that students across various programs at the university tend to score within the average range, with 487 respondents falling into this category. Notably, BA118 emerges as a program with lower SDL scores, warranting attention and potential interventions to bolster SDL capabilities among its students. Furthermore, BA118 ranks below average in terms of SDLR, signaling the importance of targeted support within this program. EC110 and AT110 also warrant consideration in terms of enhancing SDLR. However, there is no relationship between the types of courses with SDL. These findings collectively contribute valuable insights into the readiness for SDL among the Malay students and point towards the need for tailored strategies and support mechanisms to foster and elevate SDL skills among Malay students in different programs. Such efforts hold the potential to enhance overall educational outcomes and empower Malay students to navigate the challenges of lifelong learning effectively.

Recommendations for Practitioners

SDL is an essential skill that empowers individuals to take charge of their own learning journey and acquire knowledge independently. Developing SDLR in learners can be done through various intervention programs. One of the approaches is through coaching, where learners receive personalized guidance and support to set goals, identify resources, and monitor their progress. Coaching is described as the skill of a coach to provide extra professional assistance in aiding coaches to maximize and enhance their performance in specific areas (Kamruddin et al., 2020). A coach can help learners build their motivation, self-discipline, and time management skills, which are crucial for successful SDL.

Additionally, mentoring can be valuable, as experienced individuals can share their expertise, offer insights, and provide encouragement to learners. It has been acknowledged that mentoring as a guidance approach in higher education has the potential to grow, albeit not without difficulties (Crisp, 2016, cited in Tinocco-Giraldo et al., 2020). Counseling can also play a role in addressing any barriers or challenges that learners might encounter during their SDL journey, helping them develop resilience and a growth mindset.

The age factor in SDL is something that should be taken into consideration, as not all learners may be ready for independent learning at the same stage of life. As discussed in the literature review section, past researchers would relate SDL to mature learners, hence making age an important element in SDL. The findings in the study concur with the notion that most of the young adult learners are in the ‘Average’ category. This may be because the younger learners may require more structured guidance and support before gradually transitioning into SDL. Assessing the learners’ readiness and tailoring interventions to suit learners’ readiness levels will ensure a more successful and fulfilling SDL experience. As such, coaching and mentoring programs suggested above have to consider the age factor in designing suitable programs that will help to escalate the young learners’ self-directedness.

Research on SDL offers insights into learners’ readiness for independent learning, enabling practitioners to make informed decisions about the most suitable approaches and interventions for individual learners. Age and maturity are essential factors to consider, as they influence the cognitive and emotional capacity of learners to handle SDL.

Understanding the impact of culture and race on SDL is crucial for creating culturally sensitive and inclusive learning environments. Asian learners (in this study, young adult Malay learners) are influenced by their culture. SDL would suggest that a learner should take control of his or her learning and become independent. The Malays are collectivist by culture and would prefer to work collaboratively under the guidance of teachers or educators who command absolute respect (Ahmad & Majid, 2010). Hence, by acknowledging and respecting learners’ cultural backgrounds and identities, a more positive and supportive learning experience, promoting engagement and motivation can be created and eventually help the young learners to be more self directed, without sacrificing their cultural norms and values, which is not acceptable in the Asian culture.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study found that the majority of students from both campuses fall under the ‘Average’ category in terms of their SDLR. The study also revealed that students still require the guidance of a facilitator in their learning process, indicating the need for further development of SDL skills. Based on the findings, it is recommended that future studies focus on developing strategies to enhance students’ SDLR, particularly among those in the low and below-average categories. Strategies could include providing additional resources and support for SDL and creating a learning environment that encourages and facilitates SDL. Additionally, future research could explore gender differences in SDLR and investigate factors that contribute to these differences, with the aim of developing gender-specific interventions to promote SDL. Overall, the study highlights the importance of SDL in higher education and the need to support students in developing these skills for success in their academic and professional pursuits.

Notes on the Contributors

Badli Esham Ahmad is a senior lecturer in the Academy of Language Studies, Universiti Teknologi MARA Pahang Branch. He received his doctoral degree from Universiti Teknologi MARA and has twenty years’ of teaching experience. He is currently an Associate Fellow at the Institute of Biodiversity and Sustainable Development (IBSD) Universiti Teknologi MARA. His research interests and publications are in education, adult learning, self-directed learning, and Orang Asli studies. He can be contacted at email: badli@uitm.edu.my.

Zuria Akmal Saad is a lecturer at Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Pahang with over 10 years of teaching experience. She teaches subjects such as Digital Workforce and Project Management, along with other management-related courses. Currently, she is pursuing her PhD in the Faculty of Industrial Management at Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah. Her research interests encompass topics related to organizational behavior and crowdsourcing. zuria@uitm.edu.my

Azwan Shah Aminuddin is a lecturer at Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Kelantan. He has vast experience in teaching and also in research activities. All of his research publications are in the social sciences. azwanamin@uitm.edu.my

Mohd Amli Abdullah is a senior lecturer from the Faculty of Business Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA Pahang Branch. He has over 15 years of teaching experience and has been involved in numerous research projects. His current focus is on sustainable entrepreneurship among the Orang Asli. He can be contacted by email: amli_baharum@uitm.edu.my

References

Abdou, H., Sleem, W. F., & El-wkeel, N. S. (2021). Designing and validating educational booklet about self-directed learning for nursing students. International Journal of Nursing, 8(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.15640/ijn.v8n1a3

Ahmad, B. E., & Majid, F. A. (2010). Cultural influence on SDL among Malay adult learners. European Journal of Social Sciences, 16(2), 252–266. https://www.europeanjournalofsocialsciences.com/issues/ejss_16_2.html

Al-Adwan, A. S., Nofal, M., Akram, H., Albelbisi, N. A., & Al-Okaily, M. (2022). Towards a sustainable adoption of e-learning systems: The role of self-directed learning. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 21, 245–267.

https://doi.org/10.28945/4980

Allam, S. N. S., Hassan, M. A., Mohideen, R. S., Ramlan, A. F., & Kamal, R. M. (2020). Online distance learning readiness during covid-19 outbreak among undergraduate students. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 10(5), 642-657. https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v10-i5/7236

Beitler, M. A. (2000). Self-directed learning readiness at General Motors Japan.

Brandt, W. C. (2020). Measuring student success skills: A review of the literature on self-directed learning. 21st century success skills. National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment.

Brockett, R. G., & Hiemstra, R. (1991). Self-directed learning: A review of the literature. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 10(2), 117–127.

Brookfield, S. D. (2009). Self-directed learning. In. R. Maclean & D. Wilson (Eds.), International handbook of education for the changing world of work: Bridging academic and vocational learning (pp. 2615–2627). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5281-1_172

Candy, P. C. (1991). Self-direction for lifelong learning. A comprehensive guide to theory and practice. Jossey-Bass.

Cheng, P., Cuellar, R., Johnson, D. A., Kalmbach, D. A., Joseph, C. L., Castelan, A. C., & Drake, C. L. (2020). Racial discrimination as a mediator of racial disparities in insomnia disorder. Sleep Health, 6(5), 543–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2020.07.007

Cobb, R. J., Thomas, C. S., Pirtle, W. N. L., & Darity, W. (2016). Self-identified race, socially assigned skin tone, and adult physiological dysregulation: assessing multiple dimensions of “race” in health disparities research. SSM – Population Health, 2, 595–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.06.007

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Garrison, D. R. (1997). Self-directed learning: Toward a comprehensive model. Adult Education Quarterly, 48(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/074171369704800103

Guglielmino, L. M. (1977). Development of the self-directed learning readiness scale. University of Georgia.

Heo, J., & Han, S. (2018). Effects of motivation, academic stress and age in predicting self-directed learning readiness (SDLR): Focused on online college students. Education and Information Technologies, 23, 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9585-2

Hutasuhut, N. I. J., Bakar, N. M. A. A., Ghani, N. K. A., & Bilong, D. (2023). Fostering self-directed learning in higher education: the efficacy of guided learning approach among first-year university students in Malaysia. Journal of Cognitive Sciences and Human Development, 9(1), 221–235. https://doi.org/10.33736/jcshd.5339.2023

Hwang, J., & Franklin, C. (2022). Course-based undergraduate research in human resource development: a case study. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 25(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/15234223221138567

Kamarudin, M., Kamarudin, A. Y., Darmi, R., & Saad, N. S. M. (2020). A review of coaching and mentoring theories and models. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 9(2), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarped/v9-i2/7302

Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers.

Koçak, O., Yılmaz, İ., & Younis, M. Z. (2021). Why are Turkish university students addicted to the internet? a moderated mediation model. Healthcare, 9(8), 953. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9080953

Lai, C. (2015). Modelling teachers’ influence on learners’ self-directed use of technology for language learning outside the classroom. Computers & Education, 82, 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.11.005

Laine, S., Myllymäki, M., & Hakala, I. (2021a). Raising awareness of students’ self-directed learning readiness (SDLR). International Conference on Computer Supported Education. SCITEPRESS-Science and Technology Publications. https://doi.org/10.5220/0010403304390446

Laine, S., Myllymäki, T., & Hakala, I. (2021b). Self-directed learning readiness among students in higher education: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 11–7.

Li, H., Majumdar, R., Chen, M. R. A., & Ogata, H. (2021). Goal-oriented active learning (GOAL) system to promote reading engagement, self-directed learning behavior, and motivation in extensive reading. Computers & Education, 171, 104239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104239

Loeng, S. (2020). Self-directed learning: A core concept in adult education. Education Research International, 2020, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3816132

Long, M. H. (1990). Maturational constraints on language development. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 12(3), 251–285. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263100009165

Menon, B., Matus, C. D., & Laukka, J. J. (2023). Two novel approaches for the implementation and assessment of self-directed learning in the pre-clinical medical school curriculum. [preprint] https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3043551/v1

Mitchell, C. (2023). Supporting the transition to self-directed learning in ESL: A coaching intervention. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(2), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.37237/140204

Morris, T. H., & König, P. D. (2020). Self-directed experiential learning to meet ever-changing entrepreneurship demands. Education+ Training, 63(1), 23–49.

Nobaew, B. (2021, March). Evaluation of Self-directed Learning through Problem-based Learning in the Online Class During Covid-19 Epidemic. 2021 Joint International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology with ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer and Telecommunication Engineering (pp. 368–371). IEEE.

Ong, C. Y. F. S. (2019). Malaysian undergraduates’ behavioural intention to use LMS: an extended self-directed learning technology acceptance model (SDLTAM). Journal of ELT Research, 4(1), 8–25. https://doi.org/10.22236/JER_Vol4Issue1pp8-25

Premkumar, K., Vinod, E., Sathishkumar, S., Pulimood, A. B., Umaefulam, V., Samuel, P., … & John, T. A. (2018). Self-directed learning readiness of Indian medical students: a mixed method study. BMC Medical Education, 18(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1244-9

Puteh, F., Kassim, A., Devi, S., & Katamba, A. (2022). Postgraduate use of learning strategies: are the strategies related to one another? International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 12(10), 2718–2737. https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v12-i10/15008

Razali, A. B., Xuan, L. Y., & Samad, A. A. (2018). Self-directed learning readiness (SDLR) among foundation students from high and low proficiency levels to learn English language. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 15(2), 55–81. https://doi.org/10.32890/mjli2018.15.2.3

Salleh, U. K. M., Zulnaidi, H., Rahim, S. S. A., Zakaria, A. R., & Hidayat, R. (2019). Roles of self-directed learning and social networking sites in lifelong learning. International Journal of Instruction, 12(4), 167–182. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2019.12411a

Shogren, K. A., Shaw, L. M., Raley, S. K., & Wehmeyer, M. L. (2018). The impact of personal characteristics on scores on the self-determination inventory: Student report in adolescents with and without disabilities. Psychology in the Schools, 55(9), 1013–1026. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22174

Subekti, A. S. (2021). L2 learning online: self-directed learning and gender influence in Indonesian university students. JEES (Journal of English Educators Society), 7(1), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.21070/jees.v7i1.1427

Sumuer, E. (2018). Factors related to college students’ self-directed learning with technology. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(4), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3142

Tang, L., Zhu, L., Wen, L., Zhang, X., Jin, Y., & Chang, W. (2022). Association of learning environment and self-directed learning ability among nursing undergraduates: a cross-sectional study using canonical correlation analysis. BMJ Open, 12(8), e058224. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058224

Tejera, C. H., Ware, E., Hicken, M., Kobayashi, L., Wang, H., Adkins-Jackson, P., & Bakulski, K. (2023). The mediating role of systemic inflammation and moderating role of race/ethnicity in racialized disparities in incident dementia: A decomposition analysis. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2753483/v1

Tekkol, İ. A. and Demirel, M. (2018). An investigation of self-directed learning skills of undergraduate students. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 410879. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02324

Tinoco-Giraldo, H., Torrecilla Sánchez, E. M., & García-Peñalvo, F. J. (2020). E-Mentoring in Higher Education: A Structured Literature Review and Implications for Future Research. Sustainability, 12(11), 1–23. MDPI AG. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su12114344

Tough, A. (1971) The adult’s learning project. The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Wallace, J., Jiang, K., Goldsmith-Pinkham, P., & Song, Z. (2021). Changes in racial and ethnic disparities in access to care and health among us adults at age 65 years. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(9), 1207–1215. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.3922

Wijaya, D. P., & Khoiriyah, U. (2021, October). The relationship between preferences for online large-classroom learning methods and self-directed learning readiness. International Conference on Medical Education (ICME 2021) (pp. 88–94). Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.210930.016

Yin, K. Y., Yusof, R., & Abe, Y. (2022). Integrating financial literacy into economics courses through digital tools: The finlite app. Journal of International Education in Business, 15(2), 331–350. https://doi.org/10.1108/jieb-06-2021-0068

Zhang, D., & Yang, L. (2023). Assessing psychometric properties of the self-directed learning scale in Chinese university students. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 41(4), 469–477. https://doi.org/10.1177/07342829231153490

Zhu, M. (2021). Enhancing MOOC learners’ skills for self-directed learning. Distance Education, 42(3), 441–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2021.1956302