Ali Al Ghaithi, Sohar University, Oman. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9653-508X

Behnam Behforouz, University of Technology and Applied Sciences, Shinas, Oman. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0078-2757

Abdullah Khalid Al Balushi, University of Technology and Applied Sciences, Shinas, Oman. https://orcid.org/0009-0008-5291-664X

Al Ghaithi, A., Behforouz, B., & Al Balushi, A. Kh. (2023). Exploring the effects of digital storytelling in Omani students’ self-directed learning, motivation, and vocabulary improvements. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(4), 415–437. https://doi.org/10.37237/140402

Abstract

The current paper attempted to measure the effects of digital storytelling (DST) on motivation, self-directed learning (SDL), and vocabulary learning of Omani EFL students. To achieve this goal, 40 learners participated in this study, divided equally into control and experimental groups. Three main instruments were used in this study as pretests and posttests, including the Self-Rating Scale of SDL adopted from Williamson (2007), the Motivation Questionnaire adapted from Mehdiyev et al. (2017), and the researcher-designed vocabulary test. Both groups received face-to-face instructions; however, the experimental group was exposed to extra sessions for creating DST projects. The results of the study in motivation and SDL showed that both groups progressed as the results of instructions, but the experimental group was slightly better. However, in the vocabulary test, the experimental group significantly performed better than the other group. These findings can help teachers, institutions, and students better use the technological resources in language learning environments.

Keywords: digital storytelling, self-directed learning, motivation, Oman

The development of technology compels individuals to study, implement, and employ it in their daily lives, especially in instruction and learning. In addition to giving students more control and ownership over their unique learning processes, the use of technology enriches chances for student interaction with classmates, teachers, and learning resources (Dawson et al., 2012). Technology is a useful instrument for promoting self-directed learning (SDL). Technological innovations may directly impact SDL by promoting data acquisition, resulting in digital mastery (Timothy et al., 2010).

SDL has been identified as an important component of pupil achievement in twenty-first-century education. Unexpectedly, SDL has been linked to continuous learning. SDL has been identified as essential for a creative society by UNESCO and the OECD. In addition, there has been an increase in studies on self-direction among K-12 children. In summary, self-direction is now considered an essential 21st-century talent for students (Chee et al., 2011). It is now widely acknowledged to be directly involved in utilizing technology for learning within and outside the study hall. DST is an instructional method that falls under the category of SDL (Ponhan et al., 2020).

Digital storytelling (DST) uses video technology to capture learners’ experiences within the preparation process. Many applications, such as the KineMaster, may assist in the creation of DST. On the other hand, smartphones are now playing an increasingly essential role since they may be used in lieu of more expensive digital recording equipment. Students can use several smartphone apps to conveniently search for and receive information and make digital video tales. Furthermore, cell phones can facilitate outdoor learning anywhere and anytime (Murphy et al., 2014).

Yamaç and Ulusoy (2016) found that using DST to tell stories improved pupils’ ideas, organization, selection of words, sentence fluency, and writing norms. It also fostered student cooperation in the classroom and increased their willingness to write. Moreover, a study by Nassim (2018) showed the effectiveness of using digital stories to enhance students’ engagement with the learning process and advance their writing, comprehension, and imagination. Students studying English are strongly advised to use DST as a strategy. Recent research by Kallinikou and Nicolaidou (2019) demonstrated that DST improves communication and boosts motivation. Additionally, Kaminskien and Khetsuriani (2019, as cited in Ponhan et al., 2020) discovered that technology-supported learning personalization influences classroom administration practices and enhances instructor, pupil, and peer collaboration. The results of this study demonstrated that DST is an efficient and helpful instrument for enhancing instruction.

Literature Review

Digital Storytelling

According to Kuan et al. (2012), DST is defined as a brief, first-person video tale produced using a mix of recorded speech, moving pictures, music, and other noises. DST combines classic storytelling with multimedia to engage students with various technological tools to plan, edit, and construct digital narratives (Normann, 2011). It is a narrative technique in which a brief, often three-to-five-minute tale is told using voice, picture, and written text (Ohler, 2010; Robin, 2008). The DST method shares the cognitive load of task completion with computers, seeing them as intellectual collaborators in the creation of knowledge (Saloman et al., 1991).

DST is a popular instructional method because it is appealing, interactive, and immersive (Davis, 2005; Farmer, 2004; Marcuss, 2003; McLellan, 2007; Ohler, 2006; Salpeter, 2005; Warschauer & Ware, 2008; Weis et al., 2002). It is an expression medium in a learning environment that combines subject content, knowledge, and abilities from multiple curriculum areas. DST emphasizes cooperative efforts and culminates in experiences from individuals sharing their tales before concentrating on technical skills and creating high-quality media products. Using DST enables and strengthens new community connections by listening to and reflecting on experiences presented and shared online. Students may also think more thoroughly about their topics and unique experiences, clarify their knowledge, and reflect on their ideas using technological tools in the story-making procedure (Sadik, 2008). Students develop personalities and imaginations through positive assignments and activities (Dupain & Maguire, 2005). Personalized learning experiences from DST help people become active knowledge makers instead of just consumers (Ohler, 2006).

DST helps students prepare for learning experiences in which they interact with people face-to-face, practice communication, and receive feedback from peers and themselves. This is because it can help them develop self-confidence through greater achievements (Hungm et al., 2012, as cited in AlShaye, 2021). Furthermore, DST creates adaptable learning settings for improved student cooperation, judicial literacy, interaction, and technical skills gained through resource sharing (Behmer, 2005; Smeda, 2014). According to Smeda (2014), learners utilize and enhance their abilities in various Information and Communication Technology (ICT) applications throughout the digital tale production process. Students gain a better comprehension of the topic and have a more enjoyable learning experience by creating, refining, and sharing their narratives and perusing other students’ tales.

According to Ohler (2006), DST enables students to participate actively in their education rather than as passive information recipients. As a student-centered method, students create their learning via DST and experience a sense of ownership over their education. As such, students bear the least amount of authority from their instructors over their knowledge, allowing them to play a more active part in the process, whereas teachers play a less dominant role. In conventional classrooms, student engagement and involvement in learning are absent when pupils passively listen to professors, who are seen as the sole sources of information.

The use of DST as a teaching strategy encourages students to participate actively in selecting and creating materials, giving their time and energy to assignments and activities freely, and directing their own and their peers’ learning. An increasingly popular trend that has been shown to increase student motivation is using ICT-based teaching and learning methodologies. Technology-integrated tales are utilized both within and outside the classroom to encourage students to comprehend academic concepts and communicate their views and thoughts (Dupain & Maguire, 2005).

Self-Directed Learning

Humanistic philosophy and constructivist theory have ideas about SDL (Morris, 2019). The definition of SDL provided by early academic research was given as follows: “a major, highly deliberate effort to gain certain knowledge and skill (or to change in some other way)” (Tough, 1971, p. 1) or a method in which people take charge of their learning, with or without assistance from others, in determining their own learning needs, creating learning objectives, locating resources (both human and material), selecting and putting into practice effective learning strategies, and assessing learning outcomes (Knowles, 1975).

It is essential to emphasize that historically, two critical weaknesses in important academic studies on SDL may have restricted the understanding of how SDL may support creative educational results: (1) disregarding the effectiveness, nature, or utility of the learning outcomes that the process produces; and (2) disregarding the reality that SDL is usually a pragmatic procedure in adult learning (Morris, 2020). Specifically, Tough (1971) concluded that SDL is a regular and significant aspect of adulthood and frequently serves a practical purpose primarily related to an adult’s work life via strongly organized interviews with 66 Canadian adults. This is a significant research investigation of SDL. Tough (1971) thus saw SDL as a practical, life-centered activity. However, a major drawback of this research was the lack of information on the type and efficacy of the educational results obtained via the SDL method.

A more thorough examination of Knowles’ (1975) definition reveals that it does not explicitly emphasize the pragmatic aspect of adult learning despite being the most widely recognized term for SDL (Guglielmino, 2008). The definition may be seen as academic research that might be implemented as a decontextualized, nonpragmatic learning procedure. In particular, Knowles (1975) did not emphasize the role of SDL in a life-centered process motivated by the desire to overcome issues in real-world scenarios. This may seem strange, considering that Knowles (1975) said that a fundamental tenet of adult education is a practical, framed process motivated by the desire to address issues with real-world applications in their work on andragogy (Knowles, 1980). Importantly, however, many empirical studies on SDL in diverse educational environments are still framed using Knowles’ definition, ignoring the process’s pragmatic aspect (Lee et al., 2017; Nasri, 2017).

DST and SDL Skills

Pupils with SDL abilities know their learning responsibilities; they work independently without outside help; are inquisitive, enthusiastic, and self-assured; effectively manage their time; and make plans to complete their assignments (Hall, 2011). The terms are interchangeable since SDL involves establishing learning goals for developing and implementing DST. Pupils actively participate by choosing the greatest background music, offering their perspectives, and adding a special touch by recording their voices. SDL techniques, such as DST, include redefining the roles of educators and students. Students who engage in SDL must develop the knowledge and abilities to recognize and assess their learning requirements, reflect on what they have learned, and handle information critically and effectively (Patterson et al., 2002; Acar et al., 2015).

Salem (2022) investigated how online DST affected the growth of argumentative writing abilities among EAP students and enhanced student autonomy and SDL abilities. Three classes were included in the study, one of which was the control group, while the other two were randomly allocated to the experimental groups. The Learner Autonomy Scale (LAS) and the self-rating scale of SDL were used to create the argumentative writing pretest and posttest. The two experimental groups received writing instruction through two distinct modalities: Group B utilized offline content creation software to create DST to support writing abilities, whereas Group A received instruction via online storytelling. Group C, the control group, on the other hand, used a conventional narrative technique. Compared to the control group, the study’s main finding was that DST significantly and favorably affected SDL abilities among the two experimental groups.

Ponhan et al. (2020) examined pupils’ viewpoints on improving SDL using DST. Nine individuals were selected to participate in this study. After completing a general standard exam, they were divided into three groups: high, mid, and low, depending on their skill levels. The data were gathered through semi-structured interviews. These results indicated that learning via DST enhanced students’ independent learning. Educators should use this learning technique to promote SDL during teaching and in all educational contexts.

Kim (2014) studied how self-study tools such as VoiceThread, Vocaroo, and vozMe may boost English learners’ oral competency and independence. Five intermediate-to advanced-level ESL students participated in this activity. They used Vocaroo and VozMe outside the classroom to practice speaking for 14 weeks while recording stories weekly. They received an email response from their teacher. During weeks 1, 5, 10, and 14, participants used VoiceThread to recount stories about silent movie clips to assess their oral competence growth. Surveys were used to assess the sentiments. Through self-evaluation and feedback, participants’ speech greatly improved vocabulary, sentence complexity, and pronunciation. They were inspired and assisted in self-monitoring through stories. It also indicates that online resources with SDL, storytelling, criticism, and self-assessment help ESL learners enhance their oral competency and independence.

Hava (2021) examined how DST affects EFL students’ motivation and satisfaction. Sixty pre-service teachers participated in the nine-week project, which included creating three digital tales. The scale used to measure motivation (pre-/post-intervention) evaluated attitudes, self-efficacy, and personal usage. A questionnaire was used to assess the satisfaction. Small impact sizes were found in the results, indicating substantial increases in self-confidence and personal usage after the intervention. No notable shifts in perspective were observed. Students noticed increased writing, speaking, vocabulary, and computer ability. However, because they thought it would take too much time and be challenging, most students did not want to participate in another DST exercise. DST may aid in the development of digital and linguistic skills.

Aljaraideh (2020) investigated the influence of DST on the academic success and motivation of sixth graders in English in Jordan. DST is critical for the survival and development of English. A quasi-experimental design is used in this study. The study sample comprised 50 male students selected from public institutions. They were divided into experimental (n = 25) and control (n = 25) groups. The study’s results revealed significant differences in pupil achievement in school and enthusiasm to learn the English language owing to the teaching technique in favor of the experimental group in which the DST technique was the major method employed in the English language. Statistically significant variations in students’ desire to learn English were also identified in favor of the experimental group, owing to the teaching approach.

Kasami (2017) examined the differences between a Storytelling (ST) and a DST (DST) project in terms of how they impacted students’ desire to study English as a foreign language. Seventy-six undergraduates from Japan participated in the study. Students completed a midterm ST project and a final DST project as a coursework component. Utilizing pre- and post-assignment surveys, data were gathered using Keller’s ARCS model of motivation. The surveys assessed the aspects of focus, significance, assurance, and contentment. Results indicated that compared to the ST project, most learners felt that the DST project was more motivating for learning. There were notable variations in motivation across the assignments for the majority of the categories, according to an examination of the ARCS elements.

The existing literature on DST has focused mainly on teachers’ attitudes and perceptions of students in elementary schools (Fortinasari et al., 2022). Ramalia (2023) stated that further studies are needed to understand the importance of DST in higher education. Therefore, the present paper attempts to investigate the role of DST in motivation, self-directed learning, and vocabulary acquisition of undergraduate students in the language learning context. Thus, this study is an attempt to answer the following research questions:

- Does digital storytelling affect the motivation of Omani EFL students?

- Does digital storytelling affect the amount of self-directed learning of Omani EFL students?

- Does digital storytelling affect the number of vocabulary acquired by Omani EFL students1/

Methodology

Participants

This study included 40 Omani EFL learners chosen randomly from the General Foundation Program (GFP) in Oman. They were selected at the intermediate level according to the placement exam administered by the institution. They comprised a mixed group of male and female pupils. The participants’ primary language was Arabic; their ages ranged from 19 to 20. The pupils were divided into two equal groups: experimental and control. The institution requires every student to complete the foundation program before beginning their study in their area of expertise. During the obligatory foundation year, students are encouraged to study English and disciplines such as mathematics and information technology.

Research Instruments

The following instruments were utilized in the data-gathering process:

Self-Rating Scale of SDL

The self-rating scale of SDL (SRSSDL) created by Williamson (2007) was used in this study to investigate the development of pupils’ SDL abilities. The scale framework contained a brief learner profile and basic instructions. The scale had 60 items divided into five categories of SDL, each consisting of 12 elements: (1) awareness, (2) learning strategies, (3) learning activities, (4) evaluation, and (5) interpersonal skills.

The ‘always’ response was given a score of 5 for each item, and the ‘never’ response was given a score of 1. The maximum and minimum possible SRSSDL scores were 300 and 60, respectively. A scoring matrix was created to facilitate comprehension of responses (Alshaye, 2021). According to Salem (2022), the (SRSSDL) scale is reliable; the Cronbach alpha for learning strategies was 0.87 for learning activities, 0.93 for evaluation, 0.91 for interpersonal skills, and 0.88 for the entire scale. In addition, this scale has been used in various studies, including (Adnan & Sayadi, 2021; Lee, 2020). Moreover, the scale has been translated into multiple languages, including Italian (Cadorin et al., 2011).

The scale has been translated into Arabic in the current paper. To ensure that the Arabic version of the scale adhered to the same language norms, form, and style, three Ph.D. holders in applied linguistics with proven professional knowledge monitored the questionnaire. The questionnaire was then sent to an independent moderator to guarantee a more accurate tool via question moderation and the consideration of academic and cultural ethics.

Motivation Questionnaire

The motivation scale was adapted for this study, initially developed by Mehdiyev et al. (2017), and consists of 16 items. It uses the five-point Likert scale with the options (1) for ‘Totally disagree,’ (2) for ‘disagree,’ (3) for ‘partly agree,’ (4) for ‘agree,’ and (5) for ‘Totally agree.’ The scale is made up of three factors: attitude (four items), self-confidence (five items), and personal use (seven items). This questionnaire was chosen because it has been utilized in different studies (Öden et al., 2021; Önal et al., 2022). In addition, Cronbach’s alpha values for each component were .78, .77, and .85, respectively, and the total reliability coefficient was .83 (Hava, 2021).

An applied linguistics Ph.D. holder with verified professional expertise was given the questionnaire to maintain the same language standards, form, and style for Arabic translation. The statements were then transferred to an outside moderator for academic and cultural ethics and question moderation to ensure a more accurate tool.

Vocabulary Pretest and Posttest

Two vocabulary tests, a pretest and a posttest, were created to measure participants’ knowledge and progress before and after the treatment. The tests all had the same number of questions, ten, and utilized a combination of fill-in-the-blank and multiple-choice formats. The test results were analyzed using SPSS software version 16.0.

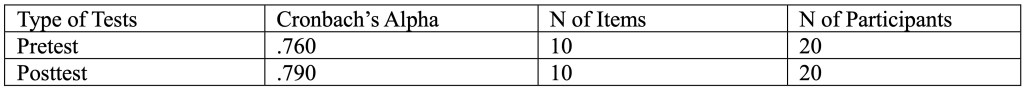

These tests were validated by two Ph.D. holders in applied linguistics who were Omani nationals with 15 years of teaching and training experience in the Omani EFL context. A pilot study was conducted with 20 Omani EFL learners to ensure the reliability of both tests. As can be observed in Table 1, the pretest and posttest implemented in this study are highly reliable, as the results of Cronbach’s Alpha show 0.760 and 0.790, respectively.

Table 1

Reliability of Pretest & Posttest

English for the 21st Century 2 Edition Book Series

The researchers selected 30 words from the second edition of English for the 21st Century. The book integrated skills and was taught during the first academic semester of 2023. This book was used as the principal text for intermediate-level students at the university. This study’s primary concern was in units three, four, and five. The research looked at 30 terms that would be taught to pupils for three weeks, with ten new words added to the vocabulary each week.

Procedure

The study was conducted throughout the academic semester in the fall of 2023. Participants were made aware that their involvement in the study was voluntary. One week prior to the treatment deployment, pretests of vocabulary, motivation, and SDL were conducted accordingly. The two groups learned vocabulary and followed the instructor’s instructions, but the experimental group utilized DST as an additional vocabulary practice outside of class. The experimental group participated in a session on producing DST before the implementation phase began. The components of DST, the programs for creating them, and the method of making them were explained to the students throughout the session. The implementation duration was three weeks. The experimental group participants created three digital stories about planning, products, and decision-making. After that, the students were introduced to several video editing applications, including PowerPoint, VivaVideo, WeVideo, Capcut, Windows Movie Maker, and Openshot. In addition, the Microsoft Team Group shared URLs to websites containing non-copyright noises, pictures, and instructions on constructing a digital narrative. The vocabulary addressed in the research consisted of 30 terms, with 10 words taught per week. Ten of the thirty words covered a particular subject.

At the beginning of each week, the first 10 words of week 1 were taught for both the control and experimental groups inside the classroom, but the experimental group was requested to write the first version of the short story using the 10 words covering the first topic outside the classroom. In addition, the students in the experimental group had to find images for the story.

Then, during the first session of English class, the experimental group students submitted the first version of the short story with images for feedback before they started to produce DST. The instructor instructed the experimental group pupils to revise their second version of the story per the feedback they received.

Later on, all experimental group students who had completed the second short-story draft got the instructor’s approval. The teacher encouraged the students of the experimental group to produce digital stories during their free time outside the classroom using their mobile phones or free lab computers. The pupils started to create digital stories by combining multimedia components and adding English subtitles at home; some started working at the lab. The students were informed to ask for any inquiries through the Microsoft Team.

Finally, after the experimental group students finished designing the digital story, each student presented DST in front of the class, and the teacher asked some questions and discussed their work with them.

In week 4, the self-rating scale for SDL, motivation scale, and posttest of vocabulary were administered to the control and excremental groups.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical issues are critical in every study because conducting research based on legal rules would be impossible without clearance. The university was approached for permission by researchers. Before the data-gathering operations began, the participants were given extra directions to read. After being promised that any information they supplied would be kept discreet, all participants voluntarily agreed to participate in the survey.

Data Analysis and Results

In this section, the descriptive data analysis is analyzed quantitatively based on the results gained from the students’ performance in two groups.

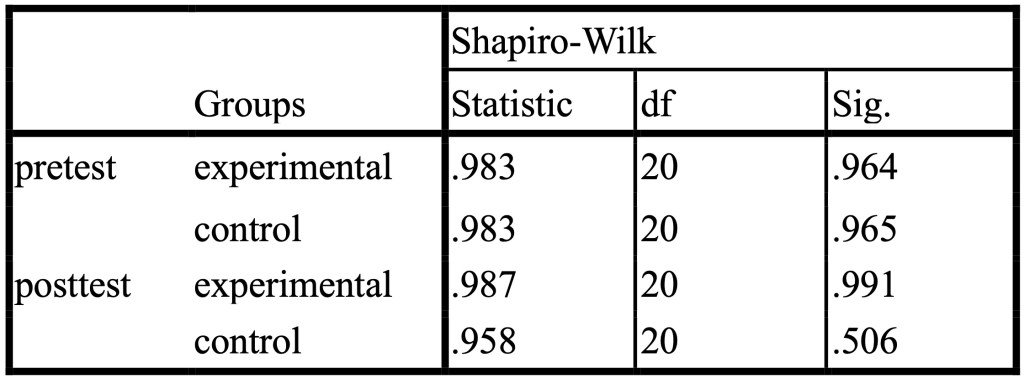

The first part of this section analyzes the results of the motivation questionnaire. Before testing the related research hypothesis, it is necessary to find the data distribution’s normality for the pretest and posttest. To do this, the researcher conducted a Shapiro-Wilknormality test; the results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Result of the Shapiro-Wilk Test of Normality

As indicated in Table 2, the normality of distribution was not confirmed for any of the score sets (p< .05), except for the pretest of the experimental group (p> .05). Therefore, the non-parametric Wilcoxon test was used to compare the pretest and posttest scores within each group. The following table shows the result of the inferential test for the control group.

Table 3

The Result of the Wilcoxon Test for the Control Group

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test in Table 3 showed no statistically significant difference between the pretest and posttest of the control group (Z = -1.159, p ≥.05). The next table compares the scores within the experimental group.

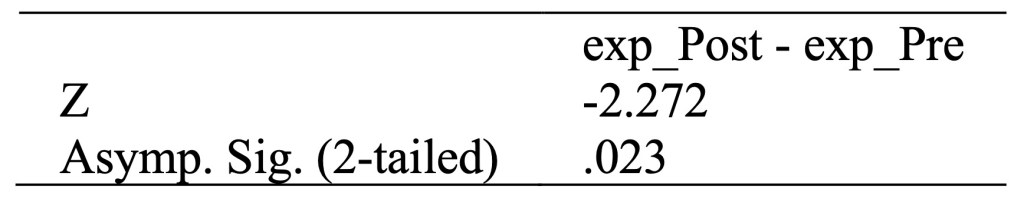

Table 4

The Result of the Wilcoxon test for the experimental Group

In Table 4, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed a statistically significant difference between the pretest and posttest of the experimental group (Z = -2.79, p <.05). The next table compares the scores between the control and experimental groups.

Table 5

Result of the Mann-Whitney U Test for the Comparison of Both Groups

As Table 5 shows, there was a statistically significant difference between the posttest scores of the two groups (U = .00, p <.05). Therefore, the experimental group participants showed higher motivation levels after implementing the DST technique in the language learning process.

The second research question focuses on using DST and SDL. The students’ results were analyzed comprehensively to measure the effect of treatment on both groups based on the SRSSDL questionnaire. Before testing the related research hypothesis, finding the data distribution’s normality for the pretest and posttest scores is necessary. To do this, the researcher conducted a Shapiro-Wilktest. Table 6 displays the results.

Table 6

Result of the Shapiro-Wilk Test of Normality

As indicated in Table 6, the normality of distribution was confirmed for all the score sets (p> .05). So, a one-way ANOVA was used to compare the pretest and posttest results.

Table 7

Results of One-Way ANOVA

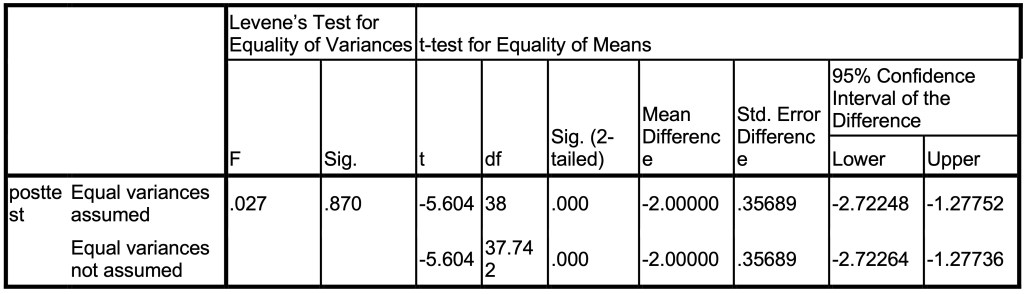

As can be observed from Table 7, the performance of students in both groups in the pretest was similar, showing the answer’s homogeneity. However, since the (p <.05) in the posttest, it can be concluded that there is a difference between the student’s pretest and posttest results. An independent T-test was run to compare both groups in the posttest and

Table 8 shows no significant difference in the performance of both groups based on SDL. This could be the result of training for both groups. However, the mean comparison of both groups shows that the experimental group performed slightly better than their counterparts in the control group.

Table 8

Analysis of Independent T-Test of posttest for Control and Experimental groups

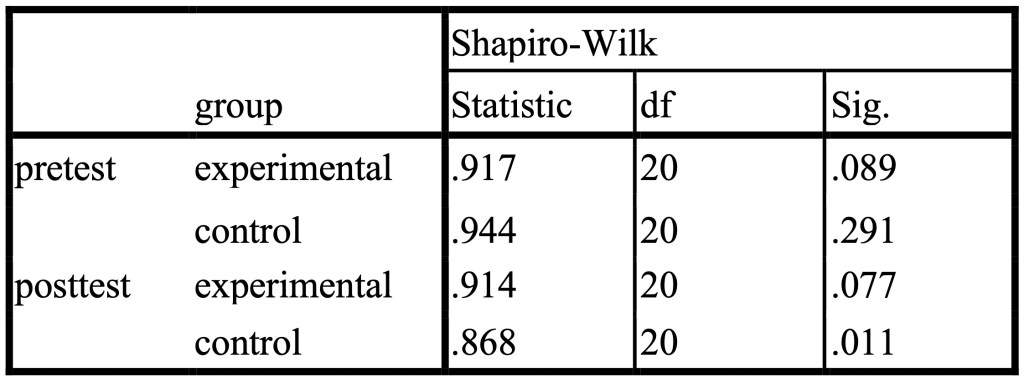

To measure the effect of DST and its impact on vocabulary learning of Omani EFL students, some statistical analysis was necessary. Before testing the related research hypothesis, it was necessary to determine whether the data distribution was normal for the pretest, posttest, and delayed scores. To do this, the researcher conducted a Shapiro-Wilktest. Table 9 displays the results.

Table 9

The Results of the Shapiro-Wilk Test of Normality

As indicated in Table 9, the normality of distribution was not confirmed for the control group pretest (p> .05). Therefore, the non-parametric Wilcoxon test was used to compare the pretest and posttest. The paired-sample was used to compare the pretest and delayed scores within the experimental group. For the control, only the non-parametric Wilcoxon test was used. Table 10 shows the result of the inferential test for the control group.

Table 10

Result of the Paired-Samples T-Test for the Pretest and PostTest of the experimental Group

As shown in Table 10, there was a statistically significant difference between the pretest and posttest of the experimental group, t (19) = -8.748, p <.05. Table 11 below compares the performance of the control group in the pretest and posttest by running a Wilcoxon test. Table 11 below shows no significant progress from the pretest to the posttest in the control group as the Z = -3.114, p >.05.

Table 11

The Result of the Wilcoxon Test for the Control Group

An independent T-test was applied to measure the effect of DST among experimental group participants and compare it with the control group. The results are shown in Tables 12 and 13. Table 12 shows a remarkable difference between the control and experimental groups` means by 4.3 and 6.3, respectively.

Table 12

The Descriptive Statistics for the Posttest

Table 13 below shows that the experimental group performed significantly better than the control group in the vocabulary posttest. So, it can be concluded that DST positively affects students in vocabulary learning.

Table 13

Independent Sample T-Test for Posttest of Both Groups

Discussion

The introduction and proliferation of Web 2.0 and comparable technologies have permitted the adoption of novel methodologies, such as DST, in foreign language instruction (Lee, 2014). DST offers pupils who struggle with self-expression in a genuine technology-based learning environment (Bull & Kajder, 2004). Implementing and designing digital narratives for English language learning in Oman constituted the main aim of this research. This study investigated the impact of DST on pupils’ motivation, SDL, and vocabulary acquisition. While the control and experimental groups were provided equivalent in-person instruction to foster motivation, SDL, and vocabulary knowledge, the experimental group benefited more from utilizing DST to enhance these attributes. The findings demonstrated that students in both groups made steady progress in SDL and motivation; however, the experimental group showed significant progress in vocabulary learning over their counterparts in the control group. Students received general instruction during class, contributing to this outcome. Consequently, this suggests that implementing digital techniques, such as the DST used in this research, could serve as a practical instrument within language learning environments.

The research findings align with several studies (DeLenardo et al., 2019; Kim, 2014; Ponhan et al., 2020; Salem, 2022) that documented the beneficial impacts of DST on students’ SDL. The study conducted by Salem (2022) examined the effect of online digital narratives on the development of argumentative writing skills between EAP pupils and their potential to promote student autonomy and SDL. The principal finding of this study was that DST significantly and positively impacted SDL abilities among the experimental group. Ponhan et al. (2020) investigated students’ perspectives regarding improving SDL through DST in a separate study. These findings suggested that DST improved students’ autonomous learning. These results are consistent with the investigation conducted by DeLenardo et al. (2019), who sought to determine whether digital narrative improves learning and engages nursing students in self-directed pathophysiological learning. The results indicated that DST positively impacted students’ SDL.

Multiple studies have reached similar conclusions to those uncovered by the second research aim (Hava, 2021; Liu et al., 2018; Kasami, 2017; Kristiawan et al., 2022), which demonstrated that learners’ motivation was enhanced through DST. Kristiawan et al. (2022) examined the efficacy of digital narrative, influenced by the pupil’s native culture, in the English language instruction of 30 junior high school students. The information gathered from the sources included focus group interviews, digital narratives, and observations. The results demonstrated that DST increased the motivation of English language learners. Hava (2021) investigated the impact of digital narratives on EFL learners’ motivation and satisfaction in a separate study. The nine-week endeavor involved the participation of 60 pre-service teachers and the development of three digital stories. Responses were collected using a survey and pre- and post-motivation rating scales. The findings of this study indicate that DST may effectively motivate students in EFL instruction. These results are consistent with those of Aljaraideh (2021) and Liu et al. (2018), who discovered that DST increases the motivation of pupils.

Another finding of this research is that pupils increase their vocabulary knowledge through DST. This aligns with some studies before this research that demonstrated the efficacy of DST in enhancing language abilities, including vocabulary (Kristiawan et al., 2022; Hava, 2021; Kim, 2014). Kristiawan et al. (2022) discovered that secondary school students gained vocabulary knowledge through DST. Students’ writing, speaking, vocabulary, and computer proficiency improve with DST in the classroom (Hava, 2021). Similarly, Kim (2014) discovered that DST improved vocabulary acquisition.

Conclusion

The main purpose of the present paper was to measure the effectiveness of DST on the vocabulary learning process of Omani EFL learners. In addition, the study attempted to measure students’ motivational levels in face-to-face and digital learning styles. Finally, this study tried to compare the SDL potential of students in both groups before and after the treatment. The findings of the study in motivation and SDL showed the progress of students in both groups, with a little bit of improvement in performance by the experimental group. However, the results of vocabulary tests in two groups before and after the digital study telling treatment showed that the experimental group performed significantly better than their counterparts in the control group.

The results are significant for teachers, educational institutions, and students. As the findings of this study revealed the positive effects of DST, teachers can consider combining face-to-face instructions and using digital materials and platforms to provide a more authentic, practical, fruitful, and rich learning environment, especially in language learning. In addition, this digitalization assists the students in being more independent of paperwork and teachers. Digitalization of the course will surely need the presence of the institution and all the human and nonhuman resources to cooperate within the environment by supplying functional and useful resources that facilitate language learning. Students are suggested to use more technological instruments and applications to be more independent in language learning and develop their critical thinking abilities and computer literacy through a type of discovery learning, such as DST.

This paper is not free of some concerns and limitations, and these can be used as suggestions for further research for researchers interested in similar areas.

- This study was conducted in one institution in Oman, and the target group was intermediate students. This limits the generalization of results, too. Since students with different GPAs select various universities, institutions might accommodate students with better computer literacy and English proficiency; thus, more studies can be conducted to better understand Oman’s DST situation. In addition, a researcher can engage students with higher or lower English proficiency levels in their future studies.

- This study was completely quantitative in nature. The questionnaires were analyzed by SPSS using only numbers. Combining the quantitative and qualitative studies is suggested further to understand Omani EFL learners’ perceptions of DST. This leads to the suggestion of engaging teachers, their perceptions, and limitations in implementing digital learning in their classes as a functional language learning technique.

- This study aimed to measure the impact of DST on the language learning process. However, marketing, social media campaigns, and employee engagement can be interactive and functional if digital storytelling is implemented correctly. Therefore, further studies on DST, social sciences, and non-academic environments like companies could be conducted.

Notes on the Contributors

Ali Al Ghaithi is an English Lecturer in the Foundation Department of Sohar University in Oman. Currently, he is a Ph.D. candidate focusing on Applied Linguistics. Ali is interested in research studies that mainly implement artificial intelligence (AI) in teaching and learning.

Behnam Behforouz is an English Lecturer in the Preparatory Studies Center at the University of Technology and Applied Sciences, Shinas, Oman. Currently, he is acting as the coordinator of the Research Committee and a member of the Research & Consultancy Committee at the university. His main areas of interest are TESOL, Applied Linguistics, Language Education, and Educational Technologies.

Abdullah Khalid Al Balushi is an English Lecturer at the University of Technology and Applied Sciences, Shinas, Oman. He received a Bachelor of Arts in Global Studies and TESOL at Nottingham Trent University. His main area of research is TESOL.

References

Acar, C., Kara, I., & Taşkin Ekici, F. (2016). Development of self-directed learning skills scale for pre-service science teachers. International Journal of Assessment Tools in Education, 2(2), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.21449/ijate.239562

Adnan, N. H., & Sayadi, S. S. (2021). ESL students’readiness for self-directed learning in improving English writing skills. Arab World English Journal, 12(4), 503–520. https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol12no4.33

Aljaraideh, Y. A. (2020). The impact of digital storytelling on academic achievement of sixth grade students in English language and their motivation towards it in Jordan. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 21(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/kx56

Alshaye, S. (2021). Digital storytelling for improving critical reading skills, critical thinking skills, and self-regulated learning skills. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 16(4), 2049–2069. https://doi.org/10.18844/cjes.v16i4.6074

Behmer, S. (2005). Literature review digital storytelling: Examining the process with middle school students. Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference, 1–23. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=89ea7641c70e57ed6bd3b9b7bae21d9606a0c79f

Bull, G., & Kajder, S. (2004). Digital storytelling. Learning and Leading with Technology, 32(4), 46–49.

Cadorin, L., Suter, N., Saiani, L., Naskar Williamson, S., & Palese, A. (2011). Self-Rating Scale of Self-Directed Learning (SRSSDL): Preliminary results from the Italian validation process. Journal of Research in Nursing, 16(4), 363–373. https://doi.org/d5gxkt

Chee, T. S., Divaharan, S., Tan, L., & Mun, C. H. (2011). Self-directed learning with ICT: Theory, practice and assessment. Singapore: Ministry of Education.

Davis, A. (2005). Co-authoring identity: Digital storytelling in an urban middle school. THEN: Technology, Humanities, Education & Narrative, 1(1), Article 1. http://www.thenjournal.org/index.php/then/article/view/32

Dawson, S., Macfadyen, L., Risko, E. F., Foulsham, T., & Kingstone, A. (2012). Using technology to encourage self-directed learing: The collaborative lecture annotation system. Ascilite 2012 – Annual Conference of the Australian Society for Computers in Tertiary Education, 246–255.

DeLenardo, S., Savory, J., Feiner, F., Cretu, M., & Carnegie, J. (2019). Creation and online use of patient-centered videos, digital storytelling, and interactive self-testing questions for teaching pathophysiology. Nurse Educator, 44(6), E1. https://doi.org/gk474j

Dupain, M., & Maguire, L. (2005). Digital storybook projects 101: How to create and implement digital storytelling into your curriculum. 21st Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning, 6, 2014.

Farmer, L. (2004). Using technology for storytelling: Tools for children. New Review of Children’s Literature and Librarianship, 10. https://doi.org/bn7mn7

Fortinasari, P., Anggraeni, C. W., & Malasari, S. (2022). Digital storytelling sebagai media pembelajaran yang kreatif dan inovatif di era new normal. Aptekmas Jurnal Pengabdian Pada Masyarakat, 5(1), 24–32.

Guglielmino, L. M. (2008). Why self-directed learning? International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 5(1), 1–14. https://www.sdlglobal.com/_files/ugd/dfdeaf_d98e41d57bfe4b159fa98e60bcf5c4d2.pdf

Hall, J. D. (2011). Self-directed learning characteristics of first-generation, first-year college students participating in a summer bridge program [Doctoral dissertation, University of South Florida]. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4335&context=etd

Hava, K. (2021). Exploring the role of digital storytelling in student motivation and satisfaction in EFL education. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 34(7), 958–978. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1650071

Kallinikou, E., & Nicolaidou, I. (2019). Digital storytelling to enhance adults’speaking skills in learning foreign languages: A case study. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 3(3), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti3030059

Kasami, N. (2017). The comparison of the impact of storytelling and digital storytelling assignments on students’motivations for learning. In K. Borthwick, L. Bradley & S. Thouësny (Eds), CALL in a climate of change: adapting to turbulent global conditions – short papers from EUROCALL 2017 (pp. 177–183). Research-publishing.net. https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2017.eurocall2017.709

Kim, S. (2014). Developing autonomous learning for oral proficiency using digital storytelling. Language Learning & Technology, 18(2), 20–35. http://dx.doi.org/10125/44364

Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Cambridge Adult Education. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED114653

Knowles, M. S. (1980). The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy. Cambridge.

Kristiawan, D., Ferdiansyah, S., & Picard, M. (2022). Promoting vocabulary building, learning motivation, and cultural identity representation through digital storytelling for young Indonesian learners of English as a foreign language. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 10(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.30466/IJLTR.2022.121120

Kuan, T. H., Shiratuddin, N., & Harun, H. (2012). Core elements of digital storytelling from experts’ perspectives, in Proceedings of the Knowledge Management International Conference (KMICe), 4–6 July, 2012, Johor Bahru, Malaysia (pp. 397–402).

Lee, L. (2014). Digital news stories: Building language learners’content knowledge and speaking skills. Foreign Language Annals, 47(2), 338–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12084

Mclellan, H. (2007). Digital storytelling in higher education. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 19(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03033420

Lee, C., Yeung, A. S., & Ip, T. (2017). University English language learners’ readiness to use computer technology for self-directed learning. System, 67, 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.05.001

Lee, J. W. (2020). Analysis of EFL learners’ argumentative writing using the adapted Toulmin model. English Language & Literature Teaching, 26(3), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.35828/etak.2020.26.3.63

Liu, K. P., Tai, S. J. D., & Liu, C. C. (2018). Enhancing language learning through creation: The effect of digital storytelling on student learning motivation and performance in a school English course. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(4), 913–935. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-018-9592-z

Marcuss, M. (2003). The new community anthology: Digital storytelling as a community development strategy. Communities and Banking, Fall, 9–13.

McLellan, H. (2007). Digital storytelling in higher education. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 19(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03033420

Mehdiyev, E., Uğurlu, C. T., & Usta, H. G. (2017). Validity and reliability study: Motivation scale in English language teaching. The Journal of Academic Social Science Studies, 54(1), 21–37.

Morris, T. H. (2019). Adaptivity through self-directed learning to meet the challenges of our ever-changing world. Adult Learning, 30(2), 56–66. https://doi.org/fcnt

Morris, T. H. (2020). Creativity through self-directed learning: Three distinct dimensions of teacher support. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 39(2), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2020.1727577

Murphy, A., Farley, H., Lane, M., Hafeez-Baig, A., & Carter, B. (2014). Mobile learning anytime, anywhere: What are our students doing? Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 18(3), 331–345. https://doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v18i3.1098

Nassim, S. (2018). Digital storytelling: An active learning tool for improving students’ language skills. International Journal of Teaching, Education and Learning, 4(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.20319/pijtel.2018.21.1429

Nasri, N. (2017). Self-directed learning through the eyes of teacher educators. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2017.08.006

Normann, A. (2011). Digital storytelling in second language learning [Master’s thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology].

Öden, M. S., Bolat, Y. İ., & Goksu, İ. (2021). Kahoot! as a gamification tool in vocational education: More positive attitude, motivation and less anxiety in EFL. Journal of Computer and Education Research, 9(18), 682–701. https://doi.org/10.18009/jcer.924882

Ohler, J. (2006). The world of digital storytelling. Educational Leadership, 63(4), 44–47. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/98782/

Ohler, J. B. (2010). Digital community, digital citizen. Corwin Press.

Önal, N., Çevik, K. K., & Şenol, V. (2022). The effect of SOS table learning environment on mobile learning tools acceptance, motivation and mobile learning attitude in English language learning. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(5), 834–847. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1690529

Patterson, C., Crooks, D., & Lunyk-Child, O. (2002). A new perspective on competencies for self-directed learning. The Journal of Nursing Education, 41, 25–31. https://doi.org/10.3928/0148-4834-20020101-06

Ponhan, S., Inthapthim, D., & Teeranon, P. (2020). An investigation of EFL students’ perspectives on using digital storytelling to enhance self-directed learning: A case study of EFL Thai learners. Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences, 18(1), 231–246. https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jhusoc/article/download/204466/164429

Ramalia, T. (2023). Digital storytelling in higher education: Highlighting the making process. Journal of Education, 6(1), 7307–7319. https://doi.org/10.31004/joe.v6i1.3993

Robin, B. R. (2008). Digital storytelling: A powerful technology tool for the 21st century classroom. Theory Into Practice, 47(3), 220–228. https://doi.org/fv6gjv

Sadik, A. (2008). Digital storytelling: A meaningful technology-integrated approach for engaged student learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 56(4), 487–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-008-9091-8

Salem, A. A. M. S. (2022). Multimedia presentations through digital storytelling for sustainable development of EFL learners’ argumentative writing skills, self-directed learning skills and learner autonomy. Frontiers in Education, 7, 884709. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.884709

Salomon, G., Perkins, D. N., & Globerson, T. (1991). Partners in cognition: Extending human intelligence with intelligent technologies. Educational Researcher, 20(3), 2–9. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X020003002

Salpeter, J. (2005). Telling Tales with Technology: Digital storytelling is a new twist on the ancient art of the oral narrative. Technology & Learning, 25(7), 18–24.

Smeda, N., Dakich, E., & Sharda, N. (2014). The effectiveness of digital storytelling in the classrooms: A comprehensive study. Smart Learning Environments, 1(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-014-0006-3

Timothy, T., Chee, T. S., Beng, L. C., Sing, C. C., Ling, K. J. H., Li, C. W., & Mun, C. H. (2010). The self-directed learning with technology scale (SDLTS) for young students: An initial development and validation. Computers & Education, 55(4), 1764–1771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.08.001

Tough, A. (1971). The adult’s learning projects. A fresh approach to theory and practice in adult learning. (2nd ed). ERIC. http://ieti.org/tough/books/alp.htm

Warschauer, M., & Ware, M. (2008). Learning, change, and power: Competing discourses of technology and literacy. In J. Coiro, M., Knobel, C. Lankshear, & D. J. Leu (Eds.) Handbook of research on new literacies (pp. 215–240). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Weis, T., Benmayor, R., O’Leary, C., & Eynon, B. (2002). Digital technologies and pedagogies. Social Justice, 29(4), 153–167. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29768155

Williamson, S. N. (2007). Development of a self-rating scale of self-directed learning. Nurse Researcher, 14(2), 66–83. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17315780/

Yamaç, A., & Ulusoy, M. (2016). The effect of digital storytelling in improving the third graders’ writing skills. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 9(1), 59–86. https://www.iejee.com/index.php/IEJEE/article/view/145