Jihan Zayed, Mustaqbal University, Saudi Arabia & Suez Canal University, Egypt https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8592-0452

Zayed, J. (2025). Establishing self-access learning centers in Saudi universities: A scoping review. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(4),673–702. https://doi.org/10.37237/202508

First published online, October 13th, 2025.

Abstract

Self-Access Learning Centers (SALCs) are spaces for developing Language Learner Autonomy (LLA). Establishing SALCs in Saudi universities is essential for addressing the challenges students face due to their limited opportunities to practice English beyond the traditional classroom setting. This research aimed to identify the practices followed to promote LLA and determine whether there have been efforts to establish SALCs in Saudi universities. A scoping review, as an approach of evidence synthesis, was used to map 25 papers published between 2010 and 2023 as addressing practices of promoting LLA in Saudi universities. These papers were examined and coded in terms of their study identification, research methodology (i.e., design, target group, instruments, place of experiment), data analysis methods, results indicating the status of LLA, and referring to an established SALC in a Saudi university. The scoping review did not only outline the current state of research on LLA in Saudi Arabia but also emphasized the necessity of establishing SALCs as a strategic response to enhance LLA. It revealed a reliance on quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods, primarily through questionnaires and interviews, yet a notable absence of experimental programs was in the synthesized papers. Most strikingly, none of these papers referred to an established SALC in any Saudi University.

Keywords: Language Learning Autonomy, Self-access Learning Centers, Saudi education, scoping review, social constructivism, meta-research, research synthesis

The concept of language learner autonomy (LLA) has recently become popular in EFL instruction in the Arab region because of a shift from being teacher-centered to being learner-centered. As a result, teachers̕ roles have been expanded to include mediators, facilitators, helpers, guides, consultants, and coordinators trying to help learners to be aware of what they utilize, control, and gain during their learning (Alharbi, 2022; Almusharraf, 2020, 2021; Alonazi, 2017; Alrabai, 2017; Alzubi & Singh, 2017; Asiri & Shukri, 2018; Dickinson, 1987). Mynard and Ludwig (2014) explored various dimensions of learner autonomy, including learner self-management or self-directed learning, which implies that learners have “a set of skills to plan their learning, (self)-set tasks, and evaluate the outcomes of their learning to proceed to the next planning and learning phase” (para. 4). Therefore, by embracing this concept of LLA, learners should take charge of their own education. According to Raya and Peeters (2015), successful learners have always been autonomous. They have a high degree of awareness of their learning and a willingness to exercise control over how they learn (Mynard, 2019). Therefore, education should cultivate autonomous learners who have the skills necessary to plan their learning and access up-to-date information from a range of sources (Alzubi & Singh, 2017; Khreisat & Mugableh, 2021).

Despite the availability of financial and infrastructural resources both within and outside the classroom, promoting LLA may be difficult in Saudi Arabia. Students often struggle to rely on their own efforts to practice English. They typically have insufficient experience, particularly outside of the classroom, which frequently stops them from trusting their individual learning ability (Asiri & Shukri, 2018). Moreover, Althaqafi (2017) discussed the challenges and traditional attitudes towards promoting LLA in Saudi education, which are learning can best happen only in classrooms under the supervision of the teacher, students’ unwillingness to be self-reliant learners as they are mainly dependent on their teachers, and low level of the target language proficiency. For her, these factors have contributed to a passive learning environment where students are expected to listen and absorb information rather than actively participate or take responsibility for their own learning. Consequently, the prevailing model of teaching and learning in most Saudi universities is one where teachers deliver content and students absorb it, which does not promote LLA.

With the recognition of the importance of LA within the Saudi educational system, the Education and Training Evaluation Commission (ETEC) has added autonomy as a third domain of learning outcomes (i.e., knowledge, skills, and autonomy) at the university level since 2022. Incorporating autonomy as a learning domain aimed to encourage university students to take ownership of their learning. However, limited opportunities and support for language learning outside the classroom lead some students to rely on private language centers and online resources to improve their English. Others may continue their language studies outside Saudi Arabia, while the majority stop developing their language skills at the level achieved at university. This highlights the need for a stronger connection between in-class learning and external support to foster continuous language development.

Many countries (e.g., Mexico, the UK, France, Thailand, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Japan, Brazil … etc.) have established SALCs to promote LLA (Mynard, 2019). In SALCs, learning advisors assist learners in making decisions to build language learning awareness by allowing them to use language, identify authentic materials, and use self-evaluation tools such as logbooks to regularly reflect on the learning process. In summary, a SALC is a place where learners can manage language learning content, pace, strategies, and resources (Mynard & Ludwig, 2014). The establishment of SALCs in Saudi universities can equip students to confront the obstacles of lifelong language leaning, utilizing the resources and assistance offered by these centers. In these centers, students get proper training, as several researchers have attested that autonomous learning is not innate and should be taught and guided (Khreisat & Mugableh, 2021; Malcolm, 2011; Mynard, 2019; Mynard & Ludwig, 2014).

Saudi school students who join universities bring with them learning habits such as rote learning, overreliance on teachers, and spoon-fed learning (Al-Saadi, 2011). On 25 April 2016, Saudi Vision 2030 was launched aiming to achieve the goal of revolutionizing economics, culture, and education. It adopted learning that encourages thinking and innovation, which created a welcoming environment for LLA. Nevertheless, the promotion of LLA in Saudi universities is still limited, especially in comparison with the worldwide movement towards establishing SALCs. The Saudi university administration usually assigns academic counselling to all instructors. However, academic counselling associated with a resource library and self-study materials may only be considered a SALC in a very narrow interpretation of the term. Saudi universities should look for ways to support students in becoming autonomous and developing practical, lifelong learning skills.

Literature Review

The concept of a student assuming responsibility for what s/he learns is not novel. Danilenko et al. (2018) traced the origins of autonomy to a Greek word meaning “setting law for oneself” (p. 1). In his book Democracy and Education, John Dewey (1916) underscored the need to establish a supportive learning environment that fosters learning persistence, rather than concentrating on students’ knowledge and subject matter acquisition. In the late 1960s, autonomy was used when societal orientation changed from material principles to social interactions and personality development. Smith (2015) traced the origins of LLA back to the Council of Europe’s Modern Language Project in 1971. One of the outcomes of that project was the establishment of the Center de Recherches et d’Applications en Langues (CRAPEL) at the University of Lorraine in Nancy, France. Yves Chalon, CRAPEL’s founder, was considered to be the father of LLA. After his death, the leadership of CRAPEL was passed on to Henri Holec who, in 1981, defined it as the learner being “capable of taking charge of his own learning” (as cited in Schmenk, 2005, p. 4). Similarly, Smith (2008) described it as learners having “the power, ability and right to learn” (p. 396).

Other related terms, which appear to be used interchangeably, include “self-instruction”, “self-regulation”, “independent learning”, “self-access learning”, “self-directed learning”, “self-study learning”, “self-education”, “out-of-class learning” and “distance learning”, to mention but a few. While these terms focus on fostering independent learning skills and strategies, Benson (2001) mentioned that they are not synonymous, as they describe various ways and degrees of learning by oneself, whereas autonomy refers to abilities and attitudes to control learning. Moreover, Chong and Reinders (2025) confirm that how LLA is implemented tends to be inconsistent and lacks detailed descriptions. This gap is significant because it hinders a thorough comparison of the impacts of various teaching and learning practices.

Essentially, LLA is fostered when learners get training to take responsibility in the language learning process, by teaching them not just what to study but also how to study. Learners can do this by understanding how to determine learning objectives, specify content and progress, decide on methods and strategies to be employed, monitor the acquisition process (rhythm, time, place, etc.), and assess what has been acquired. Khreisat and Mugableh (2021) summarized the aspects of LLA as follows:

An ideal situation for autonomous language learning to happen is when the learners have: an autonomous learning training (technical), positive attitudes and dispositions about learning autonomously (psychological) and a suitable environment or context that empowers them to take full control over the learning process (political). (p. 64)

That is, learners become autonomous when they receive suitable training, keep good attitudes, and find themselves in an environment that enables them to completely take control of their learning.

The need to involve learners in language learning has evolved into encouraging and supporting learners due to many reasons including the resources available today for language learners both inside and outside the classroom (Alzubi & Singh, 2017). In a scoping review of 61 empirical studies on LLA, Chong and Reinders (2025) highlighted the diverse conceptualizations and operationalizations of the concept, noting a limited focus on evaluations. The authors suggested implications for future research, including the need for clearer theoretical frameworks and a broader investigation of LLA beyond classroom settings.

A SALC can provide this kind of training for promoting LLA outside the classroom, as Mynard (2016) defined SALCsas “person-centered social learning environments that actively promote language learner autonomy both within and outside the space” (as cited by Mynard, 2019, p. 186); this space may be physical and virtual. She added that technology has influenced how individuals communicate and have access to resources that were available only in self-access facilities such as libraries. Klassen et al. (1998) mentioned that a SALC provides students with an independent study programme with readily accessible materials, makes available a form of help, “either through answer keys or through counselling, and possibly offers the latest technology” (p. 55).

In 1969, the University of Lorraine in Nancy, France, launched the first SALC. Since then, there were success stories from other universities that have established SALCs around the world like University of Nottingham, University of Hong Kong, University of Auckland, University of Melbourne, and Kanda University of International Studies, to mention but a few. This highlights the positive impact that SALCs can have on learners’ language learning experiences as these centers can empower them to take control of their learning, provide access to a wide range of resources, and offer support and guidance to enhance their language proficiency. According to Mynard (2019), some principles for designing an SALC are hospitable surroundings, design of spaces that facilitate social interaction, eliminating obstacles to learning, and adaptable surroundings for change. She classified Self-Access Language Centers (SALCs) into three types:

- Social-Supportive: Designed to enhance LLA as part of its mission. It offers resources and support for collaborative learning, staffed by knowledgeable personnel who conduct regular action research.

- Developing: Often an underutilized space operated by enthusiastic instructors and students, typically with minimal financial support. It functions outside official university structure and often lacks institutional recognition, relying on faculty contributions and offering significant independence.

- Administrative: Funded through grants or substantial budgets. It is prominently located and advertised in a university. While it provides necessary resources, it lacks essential elements such as a mission promoting LLA and committed staff for research.

In Saudi Arabia, language education has followed a quite traditional approach in which students rely mostly on the teacher as the major source of information. This practice has resulted in weak, dependent learners. This problem primarily begins at schools and is conveyed to tertiary institutions where high-school graduates join the university with little knowledge or even complete ignorance of the basics of the English language (Alzubi & Singh, 2017; Khreisat & Mugableh, 2021). Moreover, these learners typically lose language proficiency as they lack everyday usage. Ostovar-Namaghi and Rahmanian (2018) call this “language deskilling” as learners rarely find a chance to use what they have learned. This means that attaining linguistic proficiency can be quite challenging and demanding, especially in light of students’ passive attitude towards learning the language outside the classroom. In this stream, LLA was spotlighted with innovative visions associated with the Arab Spring protests, by the end of 2010, to help learners maintain language proficiency, depending on their preferences, likes, and dislikes.

An earlier study on promoting LLA through the establishment of SALCs in the Middle East was conducted by Malcolm (2011). This study examined the implementation of learner involvement strategies at a SALC in the College of Medicine and Medical Sciences at Arabian Gulf University, Bahrain. Despite this SALC’s modest size and limited resources, various initiatives were introduced, including required but ungraded coursework in English and a project assignment where students worked on improving a specific aspect of their English over a semester. However, no other studies were found that referred to an established SALC in the Middle East that aligns with the aforementioned definition.

LLA Theoretical Basis

Adopting constructivism as a theoretical framework for LLA, Jean Piaget (1971) confirmed that knowledge is not an image of reality. Rather, it is something that can be created using a range of resources, such as experiences, or books. Even though knowledge comes from a variety of sources, what matters most is the idea of creating and growing knowledge on its own.

Candy (1991) argues that instead of giving out instructions, learners use their own understanding to interpret, assign significance, and give meaning to the task at hand. According to him, knowledge is something that language learners create and construct rather than taught. Therefore, learners are in charge of their own learning if they can create it from a variety of experiences without the assistance of an instructor.

However, Alzahrani and Wright (2016) believe that learners can be supported by scaffolding opportunities provided as the tasks allow them to communicate with their teacher or with their peers in the target language. This scaffolding embodies Vygotsky’s (1987) zone of proximal development through communication with a knowledgeable person. Part of scaffolding that learners receive can be through advisors’ written feedback on their performances and activities or interaction with peers in a SALC.

Drawing on social constructivism, it can be determined how rich and stimulating social environments, such as a SALC, help learners make sense of new information by allowing opportunities for the negotiation of meaning in order to incorporate it into their “existing schemata” (Reyes & Vallone, 2007). Knowledge construction is facilitated by dialogue with others (Lantolf, 2000) and is enacted in a SALC through one-to-one advising sessions and interactions with peers, teachers and other people (Fitzgerald & Takahashi, 2015).

Methods

Research Questions

The present study attempted to answer the following main question:

- How can SALCs be established in the Saudi universities?

To accomplish this, it sought to address the following sub-questions:

- What are the common practices for promoting LLA in Saudi universities?

- Are there SALCs established in Saudi universities?

Objectives

The present study aimed to:

- analyze previous studies to determine the common practices for promoting LLA in Saudi universities, and

- find out if there are established SALCs in Saudi Universities.

Significance of Study

Duff et al. (2007) ascertained that research synthesis is most effective when it contributes to new perspectives and enhances future interpretations of findings and research practices. The present study adopted scoping review, a relatively new approach to evidence synthesis, producing a visual database (i.e. map) which assists the reader in interpreting where evidence exists and where there are gaps (Munn et al., 2018). It synthesized a diverse body of research, including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods, published by Saudi researchers between 2010 and 2023 to identify and map the practices for promoting LLA and efforts to establish SALCs in Saudi universities.

Design

Adopting a qualitative research design (Creswell, 1998; Munn et al., 2018), the current paper is a scoping review of 25 previous studies published by Saudi researchers in the period from 2010 to 2023.

Sample

Purposive sampling was used to identify 25 previous studies promoting LLA in Saudi Arabia for synthetic meta-analysis to code, analyze, and interpret their results. The researcher looked for papers published in journals and websites starting from 2010 to 2023; a period witnessed a shift in Saudi culture towards supporting learners generally and EFL learners specifically to be autonomous, adhering to a detailed set of steps to conduct research synthesis (Plonsky & Oswald, 2015). According to Amini Farsani and Babaii (2020), research synthesis is “the microscope” through which previous research is interpreted as well as “the telescope” through which future research could be directed.

Validity

The current study maintains ecological validity as it focused on the relationship between a real-world phenomenon and the investigation of this phenomenon in experimental contexts. Moreover, it aimed at using its results by stakeholders in similar contexts (Chong & Reinders, 2025), as the synthesized research was carried out in Saudi universities and the scoping review results will be used in the same context.

Data Collection and Analysis

Duff et al. (2007) prefer synthesis as an inclusive term that covers any form of systematic review of research. Out of its different categories, meta-analysis is less widespread than narrative accounts and vote-counting technique, where the reviewer counts how many studies report statistically significant results in support of or against a given claim. They go forward to suppose that any type of systematic review needs to explicitly tell readers about three issues: sampling of studies, scrutiny of the displayed data, and coding across studies. A scoping review distinguishes itself from other types of research synthesis in terms of its more inclusive and systematic approach to study selection.

According to Amini Farsani et al. (2021), it was not until the early 2010s that methodological issues in applied linguistics elevated to the meta-research era: “The study of research itself” or “research on research” movement. This meta-researchism requires professional scrutiny that goes directly to the gist of scientific research. In qualitative research, Merriam (2009) confirms that the researcher is the primary instrument for data analysis and collection. The synthesized 25 papers gave the researcher first-hand information needed to see the experience from the eyes of the experiencers (researchers of previous studies). The researcher’s interpretation of the data was involved in discussing the findings.

Inclusion and/or Exclusion Criteria

This stage concerns the evaluation of searched literature, a quality assurance mechanism to ensure the included literature is relevant to the scope and focus of the review. Inclusion and/or exclusion criteria are used to screen the searched literature. Usually, two levels of screening are employed: first-level screening which focuses on titles and abstracts, and second-level screening which includes full texts. Second-level screening is usually performed on articles when their eligibility remains unclear after title and abstract screening (Chong & Reinders, 2021, 2025). Table 1 presents these criteria followed in synthesizing the papers for the current scoping review.

Table 1

Inclusion and/or Exclusion Criteria for the Scoping Review

Coding Procedures

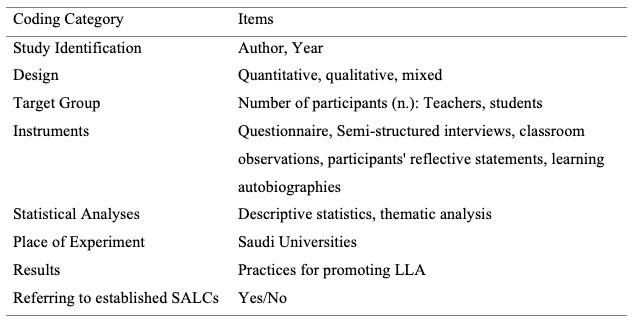

To obtain a picture of the Saudi researchers’ practices for promoting LLA, the researcher initially read the selected previous studies several times to create a coding scheme (Amini Farsani & Babaii, 2020; Plonsky & Gass, 2011; Plonsky & Oswald, 2015) which was developed and employed to extract information about each study following eight categories in terms of: (a) study identification, (b) methodological features (i.e., design, target group, instruments, place of experiment), (c) statistical analyses, (d) results indicating the current practices for promoting LLA, and (e) referring to an established SALC in a Saudi university.Table 2 clarifies this coding scheme as was applied to the synthesized body of research.

Table 2

Coding Scheme: Categories and Items

Trustworthiness

To ensure the trustworthiness of this qualitative research, several strategies were employed, aligned with the criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba (1985): credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Credibility was established as the researcher shared initial findings with peers and experts in the field for feedback, which helped validate interpretations of the meta-analysis of the synthesized papers. To promote transferability, detailed descriptions of the research context, methodology, and synthesized studies were provided. This allows readers to assess the applicability of the findings to other settings, particularly in similar educational contexts beyond Saudi universities. Dependability was addressed through external auditing to evaluate the accuracy and whether the findings, interpretations and conclusions are supported by the data. This auditing assured that the coding scheme, developed based on established frameworks (e.g. Plonsky & Gass, 2011), was consistently applied across all selected studies to minimize researcher bias. Confirmability was ensured by maintaining a transparent description of the research procedure taken from its start to the development and reporting of the findings. By implementing these criteria, the study aimed to present the findings that are credible, transferable, dependable, and confirmable, thereby enhancing the overall trustworthiness of the current research.

Results

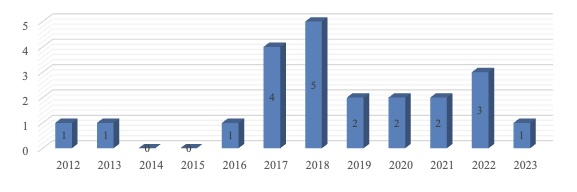

This section presents the results of the study in light of its questions. For answering the first question: What are the common practices for promoting LLA in Saudi universities?, the researcher identified 25 previous studies published between 2010 and 2023 that mostly focused on LLA in Saudi universities in an EFL context. Referring to an established coding scheme by Plonsky and Gass (2011), the researcher identified eight major categories to analyze these studies. Table 2 presented the coding scheme including categories and items elicited from the synthesized studies. Figure 1 illustrates the temporal distribution of these published studies targeting LLA, highlighting their year-based number. It shows an increasing interest in recent years, a peak was in 2017 and 2018, but that number began to decline afterward.

Figure 1

Temporal Distribution of the Synthesized Previous Studies

A scoping review of these studies between 2010 and 2023 is shown in Table 3. This scoping review included Saudi universities like Jubail Industrial College, Taif University, King Abdulaziz University, Umm AlQura University, King Khalid University, Najran University, Majmaah University, Jouf University, Taibah University, and “a Saudi public university” (mentioned in multiple studies by Almusharraf, 2018, 2019 & 2020). The total population of Alwasidi and Alnaeem’s (2022) study was selected from seven Saudi universities. Alrabai (2017b) chose his study participants from different Saudi universities.

Table 3

The Scoping Review Carried Out Using the Coding Scheme

Female students were the sample in several studies (e.g., Alghamdi, 2016; Almusharraf, 2018; Asiri & Shukri, 2018). Other studies (e.g., Alzubi et al, 2017; Haque et al., 2023; Khan & Alourani, 2022) concentrated on male students. Teachers’ viewpoints and experiences were also examined in a number of studies (e.g., Al Asmari, 2013; Alrabai, 2017b; Alwasidi, & Alnaeem, 2022; Asiri & Shukri, 2018). Both teachers and students were involved in some studies (e.g., Alharbi, 2022; Halabi, 2018; Khreisat & Mugableh, 2021).

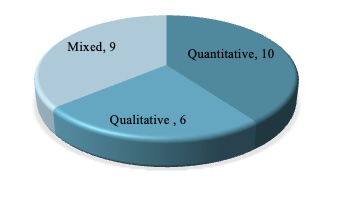

Regarding the research design of the included studies, Figure 2 presents their distribution as: quantitative research design was the most frequently used approach in these studies (10 out of 25). Mixed-methods research was also a popular choice (9 out of 25), combining quantitative and qualitative designs. Qualitative studies were less common (6 out of 25). Therefore, descriptive statistics were consistently used across quantitative studies. Thematic analysis was used for analyzing open-ended questionnaires, interview responses, classroom observations, participants’ reflective statements, and learning autobiographies. Descriptive statistics were used in conjunction with thematic analysis in mixed-methods studies.

Figure 2

Distribution of the Research Design of the Synthesized Studies

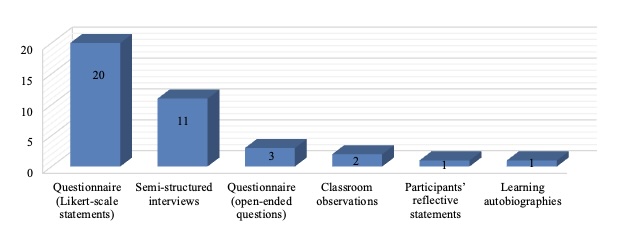

As for the instruments used, Figure 3 shows that the most popular instrument for gathering data was the questionnaire. It frequently consisted of Likert-scale (20), and occasionally open-ended questions (3). Semi-structured interviews (11) were commonly used to collect detailed viewpoints. Other instruments mentioned included classroom observations (2), participants’ reflective statements (1), learning autobiographies (1), and specific questionnaires like the Short List Questionnaire developed by Dixon (2011) was used by Alzubi et al. (2017).

Figure 3

Instruments Used in the Synthesized Previous Studies

For answering the second question: Are there established SALCs in Saudi universities? Only the study of Alzahrani and Wright (2016) explicitly referred to a SALC using Desire2Learn, a widely used virtual learning environment, and calling it self-access language learning (SALL) space to help develop LLA. Students made use of online tools such as instant messaging, a news stream, access to a facilitator, moderated discussions, videos, images, activities and quizzes, as well as links to external materials. No other research specifically referred to the impact of an established (physical) or blended SALC in Saudi Arabia on improving LLA, which reflects the need for establishing of SALCs, particularly physical ones, as an area with potential for further investigation within this context

Discussion

The scoping review aimed to meta-analyze 25 studies published from 2010 to 2023 that examined the practices for enhancing LLA in Saudi universities within an EFL context. This meta-analysis offered a detailed overview of these practices, highlighting the absence of an established SALC for promoting LLA outside the classroom. However, there were several limitations in this synthesis, stemming from the research questions and the inclusion/exclusion criteria outlined in Table 1. Additionally, some studies may not have been included due to searching certain databases (i.e., EBSCO, TESOL Quarterly, Emerald, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, ERIC, and a bibliography on learner autonomy compiled by Hayo Reinders). Moreover, the synthesized studies were coded following the methodological guidelines of Plonsky and Gass (2011).

The following paragraphs discusses the meta-analysis findings, considering three aspects for addressing LLA research as outlined in the scoping review by Chong and Reinders (2025): conceptualization, operationalization, and evaluation. In terms of LLA conceptualization, it was noted that the definition of LLA often overlaps with related concepts such as readiness for self-directed learning and self-regulated learning. Therefore, these terms were not included in the current scoping review. That is, some studies using related terms, such as Saudi students’ readiness for self-directed learning (e.g., Abdulghani et al., 2019; Abou-Rokbah, 2002; Alfaifi, 2016; Alghamdi, 2016; Alharbi, 2018; Alkorashy & Assi, 2016; Alkorashy, & Alotaibi, 2023; El-Gilany & Abusaad, 2013; Shaalan, 2019; Shahin & Tork, 2013; Soliman & Al-Shaikh, 2015) and others focusing on self-regulated learning (e.g., Alenezy et al., 2022) were excluded from this scoping review. Besides, it was observed that various theoretical frameworks have been employed (e.g., Constructivism in Asiri & Shukri, 2020; Oxford’s Model of Learner Autonomy in Alzubi & Singh, 2017; Socio-cultural Theory in Alharbi, 2022; Dixon’s Model of Learner Autonomy in Alzubi et al., 2017), but many studies lack explicit mention of their underlying theories (e.g., Khreisat & Mugableh, 2021; Alrabai, 2017a; Alzahrani and Wright; 2016).

This suggests that LLA is a topic of interest in Saudi Arabia, the EFL environment is developing slowly as there is limited research on factors that contribute to facilitating or prohibiting LLA. In this vein, there is a clash regarding the concept of LLA itself. This can be explained as Smith (2008) referred to an attempt to fit learners into preconceived models of the ideal autonomous learner, which may support the criticism that autonomy is a Western concept that is inappropriate for non-Western learners. However, he believed that enhancing LLA should be viewed as an educational goal that is cross-culturally valid.

For operationalizing LLA, the demographic distribution of studies participants comprising both male and female students, as well as teachers, suggested varied experiences and perceptions of LLA. Research that incorporates diverse perspectives could enhance the understanding of how different student and teacher populations engage with autonomous learning. In the synthesized studies, students often exhibited low levels of autonomy and perceived themselves as passive or dependent (e.g., Asiri & Shukri, 2020; Borg & Alshumaimeri, 2019; Khreisat & Mugableh; 2021), while others possessed a desire and motivation to be autonomous in Khan and Alourani (2022). Some studies highlighted the positive impact of strategy use training, and technology integration using mobile applications and smartphones on enhancing LLA (e.g., Alzubi & Singh, 2017; Alzubi et al., 2017; Alwasidi & Alnaeem, 2022; Hazaea & Alzubi, 2018). Studies (i.e., Almusharraf, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021) highlight that LLA enhances vocabulary learning, improves learning outcomes, increases intrinsic engagement and motivation, and develops self-possession and self-confidence, respectively.

A significant outcome of the analysis revealed a noteworthy discrepancy between teachers’ views of LLA implementation and students’ actual engagement or perspectives. This gap suggests that while teachers may hold certain beliefs about the effectiveness of LLA, these beliefs do not necessarily align with the realities experienced by students in the classroom. Moreover, some studies (e.g., Alharbi, 2022; Halabi, 2018; Khreisat & Mugableh, 2021) suggested that teachers needed proper training to effectively implement the practices for promoting LLA. Borg and Alshumaimeri (2019) pinpointed that teachers were less positive about LLA feasibility due to curricular, societal, and learner-related factors, all of which contribute to a more complex understanding of why LLA might not be as successful as anticipated. Teachers may feel overwhelmed by the existing curriculum, which could limit their willingness to adopt new pedagogical approaches. Additionally, societal norms and expectations about education can impose barriers, while addressing the diverse needs and backgrounds of students remains a challenge.

In a study by Asiri and Shukri (2018) at King Abdul-Aziz University, 50 English language female teachers believed that Saudi learners were non-autonomous. They relied heavily on their teachers to gain knowledge rather than seek it independently. Teachers perceived the current situation of LLA negatively. However, at the same university and in the same year, Halabi (2018) administered a survey to 44 female teachers and 480 first-year female students, in addition to in-depth interviews with 16 teachers and 15 students. The survey indicated that teachers were more positive about promoting LLA than students. However, interviews revealed that students had a high level of desirability and motivation to become autonomous. Teachers had limited experience of how it could be applied in the language classroom. One of the main contributions of this study was the insight provided into the changes occurring in Saudi society.

Research conducted in some studies (e.g., Almusharraf, 2018; Alzubi & Singh, 2017; Khreisat & Mugableh, 2021) emphasized the role of teachers in promoting LLA. Teachers use various strategies to encourage students’ independent learning, but issues such as inadequate methods for fostering autonomy and students’ lack of independence in the classroom were identified as obstacles. Therefore, these studies reported that LLA might be achieved through professional development initiatives, teaching practice reviews, implementing self-access learning time, and fewer constraints in Saudi universities.

For evaluating LLA, 10 studies included in the scoping review primarily used questionnaires to assess perceived LLA. This indicates a tendency to measure perceptions rather than tangible outcomes of LLA development. The predominance of questionnaires as a data collection instrument reflects a methodological preference that may limit deeper insights into learners’ and teachers’ experiences. Although semi-structured interviews were also employed in 9 studies, the reliance on closed questions may overlook nuanced perspectives that qualitative data can provide. The significant presence of 6 mixed-methods research underscores a growing recognition of the complexities involved in autonomous language learning.

No performance-based experiments have been conducted to explore the relationship between LLA and actual language proficiency outcomes. It could be argued that although the capacity for learner autonomy itself cannot be evaluated, observable behaviors can be researched, and this could be an indication of the degree of autonomy that a learner possesses. Almusharraf (2020, 2021) added classroom observations, participants’ reflective statements, and learning autobiographies. She recommended that professionally trained teachers should introduce students to the aims and aspects of LLA before implementing them in the curriculum. Teachers should encourage students to take responsibility for their own learning and develop awareness of their learning strategies. Since 2022, the promotion of autonomy has been incorporated into the Program Learning Objectives (PLOs) at Saudi universities, indicating a positive shift in educational policies.

Although the classroom has an important role to play in fostering LLA, Chong and Reinders (2025) recommended that future studies would more extensively investigate learners’ experiences beyond the classroom so as to better capture both the lifelong nature of autonomous learning. The current scoping review indicated that multiple Saudi universities have engaged in exploring LLA, yet there remains a notable gap in literature explicitly addressing the establishment and impact of SALCs. The unique mention of Alzahrani and Wright’s (2016) study, which used an online SALC, highlights an urgent need for targeted research into SALCs, particularly physical spaces that can foster autonomous learning environments.

A SALC provides the three aspects required for promoting LLA as mentioned by Khreisat and Mugableh (2021): technical, psychological, and political. Referring to the three types mentioned by Mynard (2019), a SALC could start by repurposing an existing facility in order to observe and systematically research how learners engage with the opportunities provided. A purpose-built SALC meeting students’ needs may follow several years later. There must still be opportunities for growth, creativity and ownership by students and staff when transitioning to Type 1, Social-Supportive, whereby several characteristics exist, such as a mission promoting LLA, sufficient assistance for learners, committed personnel to carry out research and assist students, and continued funding and institutional assistance.

Establishing SALCs at Saudi universities deserves more in-depth exploration due to their significant impact on promoting LLA. The presence of educators and facilitators in these centers allows for more direct supervision which can help in identifying students who may need additional support, thus facilitating timely interventions that can enhance learning outcomes, as SALCs often implement systematic follow-up procedures to track student progress. This could involve regular check-ins, assessments, and feedback sessions that are more manageable in a physical setting, ensuring that students remain accountable for their learning. Physical centers serve as venues for students to interact not only with instructors but also with peers. This community aspect can motivate students to engage more fully with their studies and can lead to collaborative learning opportunities. Having a physical presence allows for easier access to resources, such as learning materials, technology, and support services. This accessibility can significantly enhance the overall educational experience.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The current study utilized a scoping review as a research synthesis approach to explore studies that promoted LLA through establishing SALCs at Saudi universities. It developed a code scheme to meta-analyze 25 studies published between 2010 and 2023. The findings of this meta-analysis highlighted the different perceptions and practices of teachers and students. It was found that constraints such as teachers’ workloads and students’ reliance on teachers hinder students’ LLA enhancement in a classroom setting. SALCs could be established following the success stories of these centers in several countries for promoting LLA outside the classroom. Three types of SALCs (i.e., Social-Supportive, Developing, and Administrative) as spaces for developing LLA were presented suggesting different resources and challenges. These types can be followed in a transitional procedure to establish Social-Supportive SALCs, complying with the required aspects for promoting LLA: technical, psychological, and political, at Saudi universities. The study serves as a valuable reference for researchers and educators interested in enhancing LLA through establishing SALCs in other Arab countries.

Additionally, this study could pave the way for conducting longitudinal studies, investigating pre-university contexts, and establishing clearer connections between LLA and language proficiency outcomes with a specific focus on individual language skills (reading, writing, speaking). Based upon the synthesized studies from 2010 to 2023, it is obvious that teachers and students have different perceptions and practices towards promoting LLA. This could lead to a misunderstanding of LLA in some cases. Therefore, more training for both teachers and learners is highly recommended. Future research could benefit from increasing the use of qualitative approaches, allowing for richer data that captures the intricacies of learners’ motivations, challenges, and contextual factors influencing their autonomy. Besides, researchers are encouraged to clarify their theoretical frameworks and expand their methods to include experimental research designs. That is, there is still a persistent need for more rigorous evaluation of teaching practices that foster LLA.

Notes on the Contributor

Dr. Jihan Zayed is an Assistant Professor specializing in Teaching English as a Foreign Language. With over 20 years of experience in higher education in both Egypt and Saudi Arabia, she has published numerous articles and papers addressing topics such as online communication, mobile learning, and dialogic teaching.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Prof. Jo Mynard from Kanda University of International Studies. I was greatly influenced by her insights while reading most of her papers and research before and during the Corona pandemic. This increased my conviction of the role of LLA in fostering student independence, beyond the confines of classroom supervision. I also extend my sincere appreciation to the associate editor and peer reviewers for their invaluable time and constructive feedback on earlier versions of this paper.

References

Abdulghani, H., Almndeel, N., Almutawa, A., Aldhahri, R., Alzeheary, M., Ahmad, T., Alshahrani, A., Hamza, A., & Khamis, N. (2019). The validity of the self-directed learning readiness instrument with the academic achievement among the Saudi medical students. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health, 9(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5455/ijmsph.2020.0925030102019

Abou-Rokbah, E. (2002). Readiness for self-directed learning in Saudi Arabian students. University of Missouri-Saint Louis.

Al Asmari, A. (2013). Practices and prospects of learner autonomy: Teachers’ perceptions. English Language Teaching, 6(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v6n3p1

Alenezy, H., Yeo, K., & Kosnin, A. (2022). Impact of general and special education teachers’ knowledge on their practices of self-regulated learning (SRL) in secondary schools in Riyadh, Kingdome of Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 14(15), 9420. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159420

Alfaifi, M. (2016). Self-directed learning readiness among undergraduate students at Saudi Electronic University in Saudi Arabia (Doctoral dissertation, University of South Florida).

Alghamdi, F. (2016). Self-directed learning in preparatory-year university students: Comparing successful and less-successful English language learners. English Language Teaching, 9(7), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v9n7p59

Alharbi, H. (2018). Readiness for self-directed learning: How bridging and traditional nursing students differs? Nurse Education Today, 61, 231–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.12.002

Alharbi, N. (2022). The effect of virtual classes on promoting Saudi EFL students’ autonomous learning. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 13(5), 1115–1124. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1305.26

Almusharraf, N. (2018). English as a foreign language learner autonomy in vocabulary development: Variation in student autonomy levels and teacher support. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 11(2), 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-09-2018-0022

Almusharraf, N. (2019). Learner autonomy and vocabulary development for Saudi university female EFL learners: Students’ perspectives. International Journal of Linguistics, 11(1), 166–195. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v11i1.13782

Almusharraf, N. (2020). Teachers’ perspectives on promoting learner autonomy for vocabulary development: A case study. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1823154. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1823154

Almusharraf, N. (2021). Perceptions and application of learner autonomy for vocabulary development in Saudi EFL classrooms. International Journal of Education and Practice, 9(1), 13–36. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.61.2021.91.13.36

Alkorashy, H., & Alotaibi, H. (2023). Locus of control and self-directed learning readiness of nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study from Saudi Arabia. Nursing Reports, 13(4), 1658–1670. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13040137

Alkorashy, H., & Assi, N. (2016). Readiness for self-directed learning among bachelor nursing students in Saudi Arabia: A Survey-Based Study. International Journal of Nursing Education and Research, 4(2), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.5958/2454-2660.2016.00038.7

Alnufaie, M., & Grenfell, M. (2012). EFL students’ writing strategies in Saudi Arabian ESP writing classes: Perspectives on learning strategies in self-access language learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(4), 407–422. https://doi.org/10.37237/030406

Alonazi, S. (2017). The Role of teachers in promoting learner autonomy in secondary schools in Saudi Arabia. English Language Teaching, 10(7), 183–202. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n7p183

Alrabai, F. (2017a). From teacher dependency to learner independence: A study of Saudi learners’ readiness for autonomous learning of English as a Foreign Language. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: Gulf Perspectives, 14(1), 70–97. https://doi.org/10.18538/lthe.v14.n1.262

Alrabai, F. (2017b). Saudi EFL teachers’ perspectives on learner autonomy. International Journal of Linguistics, 9(5), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v9i5.11918

Althaqafi, A. (2017). Culture and learner autonomy: An overview from a Saudi perspective. International Journal of Educational Investigations (IJEI), 4(2), 39–48. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317235822_Culture_and_Learner_Autonomy_An_Overview_from_a_Saudi_Perspective

Alwasidi, A., & Alnaeem, L. (2022). EFL university teachers’ beliefs about learner autonomy and the effect of online learning experience. English Language Teaching, 15(6), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v15n6p135

Alzahrani, S., & Wright, V. (2016). Design and management of a self-access language learning space integrated into a taught course. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(2), 136–151. https://doi.org/10.37237/070203

Alzubi, A., & Singh, M. (2017). The use of language learning strategies through smartphones in improving learner autonomy in EFL reading among undergraduates in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of English Linguistics, 7(6), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v7n6p59

Alzubi, A., & Singh, M. (2018). The impact of social strategies through smartphones on the Saudi learners’ socio-cultural autonomy in EFL reading context. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 11(1), 31–40. Retrieved from https://iejee.com/index.php/IEJEE/article/view/587. https://doi.org/10.26822/iejee.2018143958

Alzubi, A., Singh, M., & Pandian, A. (2017). The use of learner autonomy in English as a foreign language context among Saudi undergraduates enrolled in preparatory year deanship at Najran University. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 8(2), 152–160. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.8n.2p.152

Alzubi, A., Singh, M., & Hazaea, A. (2019). Investigating Reading Learning Strategies through Smartphones on Saudi Learners’ Psychological Autonomy in Reading Context. International Journal of Instruction, 12(2), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2019.1227a

Amini Farsani, M., & Babaii, E. (2020). Applied linguistics research in three decades: A methodological synthesis of graduate theses in an EFL context. Quality & Quantity, 54(4), 1257–1283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-020-00984-w

Amini Farsani, M., Jamali, H., Beikmohammadi, M., Ghorbani, B., & Soleimani, L. (2021). Methodological orientations, academic citations, and scientific collaboration in applied linguistics: What do research synthesis and bibliometrics indicate? System, 100, 102547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102547

Asiri, J., & Shukri, N. (2018). Female teachers’ perspectives of learner autonomy in the Saudi context. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 8(6), 570–579. http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0806.03

Asiri, J., & Shukri, N. (2020). Preparatory learners’ perspectives of learner autonomy in the Saudi context. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ), 11(2), 94-113. https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol11no2.8

Benson, P. (2001). Autonomy in language learning. Retrieved on May 2, 2024, from https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=62d40e661688b62c274269f4c9a453f95f431e90

Borg, S., & Alshumaimeri, Y. (2019). Language learner autonomy in a tertiary context: Teachers’ beliefs and practices. Language Teaching Research, 23(1), 9–38.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817725759

Candy, P. (1991). Self-direction for lifelong learning. Jossey-Bass.

Chong, S. W., & Reinders, H. (2021). A methodological review of qualitative research syntheses in CALL: The state-of-the-art. System, 103, 102646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102646

Chong, S. W., & Reinders, H. (2025). Autonomy of English language learners: A scoping review of research and practice. Language Teaching Research, 29(2), 607–632. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221075812

Creswell, J. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Sage.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. The Free Press.

Dickinson, L. (1987). Self-instruction in language learning. Cambridge University Press.

Duff, P., Norris, J., & Ortega, L. (2007). The future of research synthesis in applied linguistics: Beyond art or science. TESOL Quarterly, 41(4), 805–815. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40264408

Danilenko, A., Kosmidis, I., Shershneva, V., & Vainshtein, Y. (2018). Learner autonomy in modern higher education. SHS Web of Conferences 48, 01002 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20184801002 ERPA 2018

El-Gilany, A., & Abusaad, F. (2013). Self-directed learning readiness and learning styles among Saudi undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 33(9), 1040–1044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.05.003

Fitzgerald, C., & Takahashi, K. (2015). Developing a peer support network in a self-access learning center. Digital Independence: The Newsletter of The Learner Autonomy Special Interest Group (17th October 2015), 9–12.

Halabi, N. (2018). Exploring learner autonomy in a Saudi Arabian EFL context (Doctoral dissertation, University of York).

Haque, M., Jaashan, H., & Hasan, M. (2023). Revisiting Saudi EFL learners’ autonomy: a quantitative study. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 17(4), 845–858. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2023.2166512

Hazaea, A., & Alzubi, A. (2018). Impact of mobile assisted language learning on learner autonomy in EFL reading context. Journal of Language and Education, 4(2), 48–58. https://doi.org/10.17323/2411-7390-2018-4-2-48-58

Javid, C. (2018). A gender-based investigation of the perception of English language teachers at Saudi universities regarding the factors influencing learner autonomy. Arab World English Journal, 9(4), 310–323. https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol9no4.23

Khan, R., Ali, A., & Alourani, A. (2022). investigating learners’ experience of autonomous learning in E-learning context. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 17(8), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v17i08.29885

Khreisat, M. & Mugableh, A. (2021). Autonomous language learning at tertiary education level in Saudi Arabia: students’ and instructors’ perceptions and practices. International Journal of Arabic-English Studies, 21(1), 61–82. https://doi.org/10.33806/ijaes2000.21.1.4

Klassen, J., Detaramani, C., Lui, E., Patri, M., & Wu, J. (1998). Does self-access language learning at the tertiary level really work. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 8, 55–80. https://www.cuhk.edu.hk/ajelt/vol8/art4.htm

Lantolf, J. (2000). Second language learning as a mediated process. Language teaching, 33(2), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444800015329

Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8

Malcolm, D. (2011). Learner involvement at Arabian gulf university self-access centre. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 2(2), 68–77. https://doi.org/10.37237/020203

Merriam, S. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass.

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC medical research methodology, 18, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Mynard, J. (2019). Self-access learning and advising: Promoting language learner autonomy beyond the classroom. In H. Reinders, S. Ryan, & S. Nakamura (Eds), Innovation in language teaching and learning: The case of Japan (pp. 185–209). New Language Learning and Teaching Environments Series. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12567-7_10

Mynard, J., & Ludwig, C. (2014). Introduction: Tools, tasks and environments for learner Autonomy. In J. Mynard & C. Ludwig (Eds.) (2014). Autonomy in language learning: tools, tasks, and environments. IATEFL. https://www.academia.edu/7912049/Autonomy_in_language_Learning_Tools_Tasks_and_Environments

Ostovar-Namaghi, S., & Rahmanian, N. (2018). Exploring EFL learners’ experience of foreign language proficiency maintenance: A phenomenological study. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 7(1), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.7n.1p.32

Piaget, J. (1971). The theory of sages in cognitive development. In D. Green, M. P. Ford, & G. B. Flamer (Eds.), Measurement and Piaget (pp. 1–11). McGraw-Hill.

Plonsky, L., & Gass, S. (2011). Quantitative research methods, study quality, and outcomes: The case of interaction research. Language Learning, 61(2), 325–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2011.00640.x

Plonsky, L., & Oswald, F. (2015). Meta-analyzing second language research. In: Plonsky, L. (ed.) Advancing Quantitative Methods in Second Language Research, pp. 106–128. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190510000115

Raya, M., & Peeters, W. (2015). Reflections on the second webinar in the IATEFL LASIG series: The value of experience in teacher education for learner autonomy. Digital Independence: The Newsletter of The Learner Autonomy Special Interest Group (17th October 2015), 29–32.

Reyes, S., & Vallone, T. (2007). Constructivist strategies for teaching English language learners. Corwin Press.

Saudi Education and Training Evaluation Commission (ETEC) (2022, January 13). Program Accreditation: Documents. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://etec.gov.sa/ar/service/accreditation/servicedocuments

Saudi Vision 2030 (2016, April 25). Vision Realization Programs. Retrieved February 9, 2025, from https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/explore/programs

Schmenk, B. (2005). Globalizing learner autonomy. TESOL Quarterly, 39(1), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588454

Shaalan, I. (2019). Remodeling teachers’ and students’ roles in self-directed learning environments: The case of Saudi context. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 10(3), 549–556. http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1003.19

Shahin, E., & Tork, H. (2013). Critical thinking and self-directed learning as an outcome of problem-based learning among nursing students in Egypt and Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 3(12), 103. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v3n12p103

Smith, R. (2008). Learner autonomy. ELT Journal, 62(4), 395–397. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccn038

Smith, S. (2015). Learner autonomy: Origins, approaches, and practical implementation. International Journal of Educational Investigations, 2(4), 82–91. http://www.ijeionline.com/attachments/article/41/IJEIonline_Vol.2_No.4_2015-4-07.pdf

Soliman, M., & Al-Shaikh, G. (2015). Readiness for self-directed learning among first year Saudi medical students: A descriptive study. Pak J Med Sci., 31(4): 799–802. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.314.7057

Vygotsky, L. (1987). The collected works of LS Vygotsky: The fundamentals of defectology, 2. Springer Science & Business Media.