Nima ZabihiAtergeleh, Department of English, Qaemshahr Branch, Islamic Azad University, Qaemshahr, Iran. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7591-8444

Mehrshad Ahmadian, Department of English, Qaemshahr Branch, Islamic Azad University, Qaemshahr, Iran. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2105-6818

Shaban Najafi Karimi, Department of English, Qaemshahr Branch, Islamic Azad University, Qaemshahr, Iran. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0018-8280

ZabihiAtergeleh, N., Ahmadian, M., & Najafi Karimi, S. (2025). The motivational paths to self-regulated language learning: A structural equation modeling approach. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(1), 123–152. https://doi.org/10.37237/202501

Published online first on 22 January 2025.

Abstract

Successful second language (L2) acquisition demands effective self-regulated language learning (SRLL), often influenced by students’ motivation. Through structural equation modeling, the present study explored the relationships between the L2 motivational self system (L2MSS) components, including the ideal L2 self, English learning experience, ought-to L2 self, and SRLL. To this end, 613 high school English language learners completed the L2MSS questionnaire designed by Taguchi et al. (2009) and an SRLL questionnaire developed by Salehi and Jafari (2015). Pearson correlation analysis revealed strong positive relationships between the ideal L2 self, English learning experience, and all SRLL subscales. Much lower but statistically significant correlations were also found between the ought-to L2 self and SRLL constituents. The structural models revealed that both the ideal L2 self and English learning experience can significantly contribute to the affective, (meta)cognitive, and behavioral aspects of SRLL through intrinsic motivation (IM). Nevertheless, the ought-to L2 self was revealed to have negligible effects on all variables. The results emphasize the mediating role of IM in a motivational model depicting the paths to SRLL. The study concludes with a discussion of implications for language learning and teaching.

Keywords: L2 motivational self system, self-regulated language learning, structural equation modeling approach

In recent years, many studies have been conducted to unravel the nature of self-regulated learning (SRL). The theory highlights the “agentic role of the learner” (Efklides, 2011, p. 6). As she defines it, this role is learners’ ability to set goals and evaluate the learning process results (Efklides, 2011). Research consistently demonstrates a strong positive relationship between self-regulated learning (SRL) and academic achievement (Cleary & Kitsantas, 2017; Lai & Hwang, 2016; Mizumoto, 2013; Seker, 2016; Zimmerman, 1990). According to Boekaerts (1996), motivation, cognition, and metacognition are the fundamental elements in the conceptualization of SRL, and results of previous studies (i.e., Pintrich, 2004; Schunk, 2005) have confirmed that SRL involves the process of monitoring and controlling motivation, cognition, behavior, and the environment. According to Schunk and Zimmerman (2023), several models have been proposed based on many theoretical frameworks. In most cases, one of the most critical aspects of SRL is the learners’ utilization of various cognitive and metacognitive strategies to control and regulate their learning (Efklides, 2011; Greene & Azevedo, 2007; Zeidner et al., 2000). Other studies consistently highlight the positive impact of motivation on SRL (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2008). Besides, self-regulated learners often perceive school materials as valuable and engaging (Boekaerts, 2011; Pintrich, 2000).

Literature Review

Self-Regulated Learning and Self-Regulated Language Learning

SRL is based on models and frameworks that shed light on cognitive, metacognitive, and affective processes (Şahin Kızıl & Savran, 2018; Su et al., 2018). Earlier scholars (e.g., Zimmerman, 2000) defined SRL as a cyclical system of processes (i.e., setting goals, planning, using strategies, monitoring, and reflecting). Over the past few decades, several theoretical models of SRL have emerged to shape the current SRL, which continues to evolve (Efklides, 2011; Pintrich, 2000; Winne & Hadwin, 1998; Zimmerman, 2000). SRL reflects Bandura’s (1986) Social Cognitive Theory and values observational learning and self-efficacy. Several major SRL models also incorporate motivation as a critical component of SRL because regulating one’s learning is an effortful process contingent upon motivation (e.g., Efklides, 2011; Zimmerman, 2000). Current studies (Su et al., 2023) revealed that increasing self-efficacy is a motivational catalyst to help learners participate in SRL activities.

Self-regulated language learning (SRLL) refers to the learning process (e.g., setting goals, planning learning strategies, monitoring progress, and reflecting on learning experiences) in which learners control, monitor, and regulate to fulfill language learning objectives (Yoon et al., 2021). Thus, self-regulated learners can be defined as learners who can actively monitor, control, and regulate their learning process, including knowing what language learning strategies work for them and taking responsibility for their progress (Zhang & Zhang, 2019). That is why SRLL is said to be a dynamic and active process that helps learners develop both effective foreign language instructional strategies (Teng, 2022) and autonomy in their language learning (Kumar et al., 2023). The connection of SRLL to language development and language acquisition was shown in recent studies. An et al., (2021), for example, indicated the significance of SRLL in improving language development and proficiency in foreign language learners whereas Bai et al. (2020) saw SRLL as a crucial ability for successful language acquisition.

Second Language (L2) Motivation

Studies on language learning motivation were initiated mostly with Gardner and Lambert’s (1972) theories, which emphasized the value of culture and attitude towards language learning and argued that integration into the L2 community is the key to success in language learning. This idea was later criticized, mainly because it neglected the unique characteristics of each learning environment and communication context (e.g., Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2009). Early L2 motivation research primarily focused on the dichotomy of extrinsic motivation and intrinsic motivation (IM), influenced by theories such as self-determination and attribution (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Previous perspectives have expanded to incorporate the impact of social context, learner identity, and self-concept on L2 motivation (e.g., Higgins, 1987; Markus & Nurius, 1986). Inspired by such theories of motivation, Dörnyei (2009) made a clear distinction between the ought-to L2 self and the ideal L2 self. According to Dörnyei (2009), the ought-to L2 self represents the attributes an individual believes they should possess to meet external expectations (e.g., societal norms, parental expectations), while the ideal L2 self reflects personally desired qualities and aspirations. Dörnyei (2009) also pointed out that learners’ attitudes towards learning English can be regarded as another main component of the theory, and they can be affected by the characteristics of the educational environment and learners’ experience of language learning.

Motivation and SRLL

Students with self-regulated skills use cognitive, motivational, and behavioral strategies to manage their learning processes, as expressed by Zimmerman (1990). Motivation plays a crucial role in self-regulation as students with self-regulation actively monitor their learning processes and can achieve educational success (Kitsantas et al., 2009; Winne, 2001; Zimmerman, 2002). SRLL is related to motivation since it can improve motivation on the one hand, as shown in previous studies (e.g., Zhang et al., 2020). On the other hand, it can be enhanced through IM and engagement prompted by a supportive and engaging learning environment, as demonstrated in research (e.g., Su et al., 2023). Motivation significantly impacts self-regulation, whereas the relationship may not always be apparent (Kim & Kim, 2014).

Earlier studies indicated that instructing students in self-regulation skills can promote motivation and provide a reciprocal relationship between these constructs (Schmitz & Wiese, 2006; Stoeger & Ziegler, 2008). As Wolters and Pintrich (1998) found, a strong correlation exists between students’ motivation and SRL strategies, particularly in how motivated students can employ effective strategies in their learning. In other words, when students perceive a subject, such as language learning, to be intriguing and valuable, they are more willing to self-regulate their learning processes (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990; Pintrich et al., 1993). In a similar vein, Zimmerman and Schunk (2008) contended that constant motivation is essential for sustaining and enhancing students’ self-monitoring skills. Eventually, this continuous motivation allows students to manage their learning more effectively.

L2 motivational self system (L2MSS) theoretical framework (Dörnyei, 2009), which emphasizes the role of self-perception in language learning, is closely linked to self-regulated L2 learning. Kim and Kim (2014) claimed that L2MSS, which involves the ideal L2 self and the ought-to L2 self, is a motivational tool that encourages active engagement in language learning by highlighting the value of self-images. Other studies (e.g., Abdollahzadeh et al., 2022; Dunn & Iwaniec, 2022; Ishida et al., 2024) have also supported the connection between self-regulation and L2 learning motivation. McCombs (2001) also mentioned that self-concept is a crucial source of motivation for engaging in SRL. Similarly, Borkowski and Thorpe (1994) stated that possible selves are related to SRL. According to their explanation, an essential part of SRL is its goal-directedness, and possible selves comprise goals. They further argued that imagining desired future outcomes or preventing negative consequences motivates learners to take action. These goal-directed efforts are the foundation of SRL.

Motivation has been considered an essential component in almost all SRL models and studies, and teaching and learning have demonstrated positive relationships between IM and SRL (e.g., Panadero, 2017; Zimmerman & Schunk, 2008). Self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985) predicts motivation and engagement based on the importance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, which are subcategories influencing IM. Earlier studies (e.g., Wolters et al., 1996) revealed that IM, proposed by Deci and Ryan (1985), plays a significant role in SRL. Studies (e.g., Tsuda and Nakata, 2013) also revealed that IM, self-efficacy, and autonomy are part of complex factors that pertain to language learners’ SRL. Therefore, it can be said that Dörnyei’s constructs, such as the L2MSS, relate to IM by highlighting how individuals’ internal drives (e.g., the ideal L2 self and ought-to L2 self) can serve as subcategories of IM (Dörnyei, 2009).

Various studies of SRL also highlight the interplay among cognitive, motivational, and affective processes. Boekaerts’ (1997) model consists of two fundamental elements: cognitive and motivational self-regulation. As she stated, cognitive regulation includes both cognitive and behavioral aspects. Motivational self-regulation, on the other hand, involves motivational, affective, and social aspects. She also noted that all of these different components within the model are closely interrelated. Building on this, Zimmerman and Schunk (2008) identified motivational processes, such as self-efficacy, goal setting, attribution, self-concept, self-esteem, and achievement values, as vital components of SRL. Furthermore, Zimmerman and Moylan’s (2009) model highlighted critical factors influencing learner motivation (i.e., self-efficacy, outcome expectations, task value, and goal orientation) that are crucial in their forethought phase (i.e., the initial stage in SRL). Ultimately, Efklides (2011) developed a more modern SRL framework. Her Metacognitive and Affective Model of Self-Regulated Learning (MASRL) indicated that motivation interacts with affect and metacognition, and these three model components influence SRL.

In a study investigating the relationship between L2 motivation and English language learners’ SRL, Zheng, et al. (2018) used structural equation modeling (SEM) to analyze quantitative data (e.g., questionnaires) obtained from 293 Chinese university students and disclosed that ideal L2 self, instrumentality, promotion and interest in L2 culture strongly predict all the factors of online self-regulation. They also reported the factorial structure in Online Language Learning Motivation (OLLM) and Online Self-Regulated English Learning (OSEL). OLLM is composed of three parts with five factors: the ideal L2 self (instrumentality-promotion and cultural interest), the ought-to L2 self (instrumentality-prevention and others’ expectations), and the online English learning experience, which is in line with the findings of You and Dörnyei (2016). OSEL includes six factors goal setting, time management, environment structuring, help seeking, task strategies, and self-evaluation. As argued by Barnard et al. (2009) and supported by Zheng et al. (2016), these factors contribute to the factorial structure of OSEL.

Despite the mounting research evidence supporting the role of motivation in SRL (Boekaerts, 1997; Tsuda & Nakata, 2013; Wolters et al., 1996; Zheng et al., 2018), there is no empirical model that illustrates how specific motivational variables such as self-efficacy, IM, and goal orientation are linked with the motivational, affective, (meta)cognitive, and behavioral components of SRL. Because of the ambiguous nature of the concept and the lack of research on self-regulation in this area, this study aimed to explore SRL in a field that requires further investigation. As a result, the present study clarifies the relationships between various components of SRLL and the L2MSS, a widely researched theory in L2 communication. Therefore, the following research question is addressed to achieve this goal: Which motivational variables have the strongest effects on different components of SRLL?

Methodology

Participants

Due to diverse populations and accessibility for data collection, the participants were recruited based on their school location and willingness to participate in the study. Therefore, the final sample consisted of 613 English language learners (186 females and 427 males) selected from three public urban senior high schools in Sari, Mazandaran province, Iran. The participants in the 10th, 11th, and 12th grades were 241, 316, and 56, respectively. Iran’s educational system follows the K-12 model. The mean age was 16.57; 99 percent of the participants were between 15 and 20 years old, and the rest were junior English teachers in teacher education university students in Sari, Mazandaran province, Iran. As the majority of the participants were under 18, parental consent was obtained in addition to official consent from educational administrators (educational department and school principals). Both students and their parents signed consent forms to confirm their participation agreement. Convenience sampling was used to select the students who agreed to assist in the data collection and filled out the consent forms.

Instruments

L2 Motivational Self System Questionnaire

The instrument employed to measure learners’ motivation was a questionnaire developed and validated by Taguchi et al. (2009). The questionnaire, consisting of several subscales, aimed to measure ten components of the L2MSS: criterion measures, ideal L2 self, ought-to L2 self, family influence, instrumentality promotion, instrumentality prevention, attitudes to learning English, cultural interest, attitudes to L2 community, and integrativeness. The original version of the questionnaire consists of 76 items in English (see Taguchi et al., 2009), which was then translated into Persian and validated by Khaleghizadeh et al. (2020). The questionnaire demonstrated reliability values greater than 0.7 and convergent validity above 0.5. The translated questionnaire is comprised of 76 items including statement-type measured by six-point Likert scales (six-point rating scales with ‘strongly agree’ located on the left end and ‘strongly disagree’ on the right end) and question-type items (six-point rating scales with ‘not at all’ located on the left end and ‘very much’ on the right end). Cronbach Alphas reliabilities of ideal L2 self (six items), ought-to L2 self (six items), and attitudes to English language learning (six items) were .87, .85, and .87, respectively (See Table 1).

SRLL Questionnaire

A 40-item questionnaire developed and validated by Salehi and Jafari (2015) was used to measure different components of SRLL. This questionnaire was answered based on a six-point Likert scale (a six-point rating scale with ‘strongly agree’ located on the left and ‘strongly disagree’ on the right). The questionnaire was both in English and Persian (translated from English). Since the translated version of the L2MSS was utilized, the Persian SRLL questionnaire was also employed. As noted by Salehi and Jafari (2015), this instrument features the highest number of subscales (13 in total) compared to other similar tools (e.g., Kadioglu et al., 2011; Tseng et al., 2006). The subscales include IM, self-efficacy, locus of control orientation, attitude, organization, memory strategies, self-monitoring, self-evaluation, planning and goal setting, effort regulation, regulation of environment, and help seeking. The present study examined IM, self-efficacy, attitude, organization, memory strategies, self-monitoring, self-evaluation, concentration and sustained attention, and regulation of environment (9 out of 13). Its construct validity is supported by confirmatory and exploratory factor analysis, and its reliability coefficient is adequate. Therefore, its characteristics can enhance the validity of measurement. The original Salehi and Jafari’s (2015) questionnaire include 13 subscales and 65 items. However, several items (i.e., the locus of control orientation, planning and goal setting, effort regulation, and help seeking) had to be deleted as their Cronbach Alpha reliabilities were below .50. Two items under IM and memory strategies were also removed from calculations to increase the reliability of the data associated with these two scales. As mentioned by Dörnyei & Taguchi (2009), researchers need to be cautious about the reliability values below .60. Table 1 shows that except for self-evaluation, other reliability values are at least .60, which can be considered acceptable (Dörnyei & Taguchi, 2009).

Table 1

Components of L2 Motivational Self-System and SRLL With Cronbach Alpha Coefficients

Procedures

The data collection procedure involved two primary stages. In the first stage, arrangements were made with three senior high schools, and informed permission was obtained after providing explanations about the purpose of the study. In the next stage, students who showed their agreement to participate in the study by completing a consent form filled out the L2MSS and SRLL questionnaire. The instructions appeared on the first page of each questionnaire, and the participants responded to the questions in 30 minutes. Each questionnaire (L2MSS and SRL) took 30 minutes and was conducted in two separate class sessions, and all the participants were thanked in person after the data collection procedure.

Data Analysis and Results

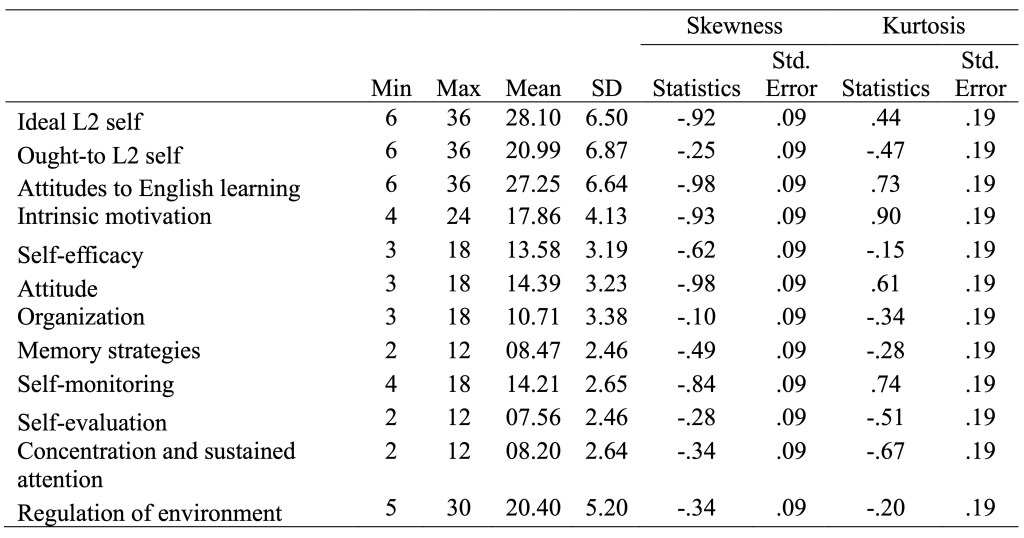

Initially, 613 participants participated in the current study; however, only 312 were used as the final samples. Due to challenges during the COVID-19 period, health issues, high school restrictions, and incomplete questionnaires, all 613 participants could not participate in both data collection sessions and, as such, were excluded from the study to ensure the best possible outcomes. Only those who fully completed the questionnaires and were present at the data collection sessions were included in the study. The final dataset, consisting of responses from participants who answered nearly all questions in both questionnaires during two 30-minute sessions, was entered into SPSS 26 for analysis using the SEM approach. Therefore, the mean substitution method was used to replace them and prepare the data for the analysis (Hair et al., 2014). Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the obtained data:

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics of the Components

The skewness and Kurtosis of all the subscales fell within limits of ±2. Since these values have been approved as the acceptable range for normal distribution (e.g., Gravetter and Wallnau, 2014), it was concluded that the data were normally distributed.

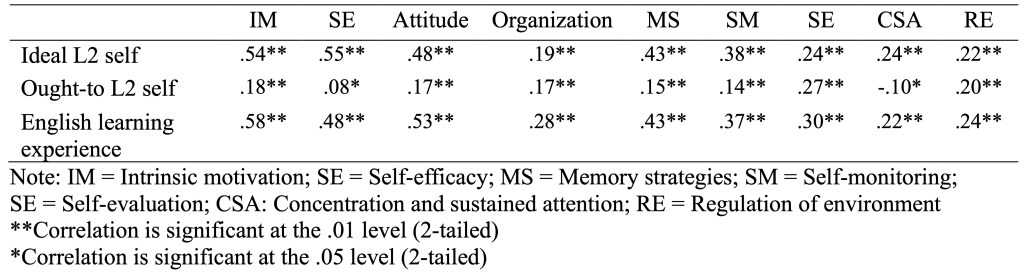

Table 3 displays the results of the Pearson Product-Moment correlation. As shown in the table, the strongest correlations can be found between the motivational and affective components of SRLL and two of the motivational variables: ideal L2 self and English learning experience. Ideal L2 self is significantly correlated with IM (r = .54, p = .002), self-efficacy (r = .55, p = .001), and attitude (r = .48, p = .001). The table also indicates significant positive correlations between English learning experience and IM (r = .58, p < .05), self-efficacy (r = .48, p < .05), and attitude (r = .53, p < .05). Moreover, the results indicate mostly weaker but statistically significant correlations between ideal L2 self and (meta)cognitive/behavioral dimensions: organization (r = .19, p < .05), memory strategies (r = .43, p < .05), self-monitoring (r = .38, p < .05), self-evaluation (r = .24, p < .05), concentration and sustained attention (r = .24, p < .05) and regulation of the environment (r = .22, p < .05). A similar pattern of correlations can also be found between English learning experience and (meta)cognitive variables: organization (r = .28, p < .05), memory strategies (r = .37, p < .05), self-monitoring (r = .37, p < .05), self-evaluation (r = .27, p < .05), concentration and sustained attention (r = .22, p < .05) and regulation of the environment (r = .24, p < .05). Additionally, the correlations between ought-to L2 self and components of SRLL are mostly weak though statistically significant (p < .01). Except for a weak negative correlation which exists between ought-to L2 self and concentration, other variables are positively correlated with this variable (See table 3).

Table 3

Correlations Between Motivational Variables and Components of SRLL

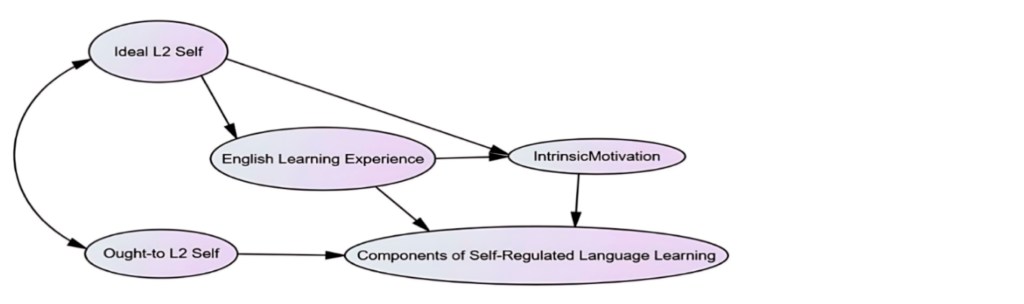

After ensuring that the subscales were interrelated, a conceptual model was developed drawing upon Taguchi et al.’s (2009) model of L2MSS and theories of SRL (e.g., Boekaerts, 1997; Efklides, 2011). Figure 1 shows the relationships among the three main components of the L2MSS, including the ideal L2 self, English learning experience, and ought-to L2 self, as well as variables of SRLL. IM, the only motivational component within the framework of SRLL, is also part of the hypothetical model (See Figure 1).

Figure 1

The Initial Hypothetical Model of L2MSS and Various Components of SRLL

The appropriateness of the model was assessed using the indices commonly referred to in the previous studies (e.g., Taguchi et al., 2009; Tseng et al., 2006). Table 4 shows the extent to which the model is appropriate to describe the relationships between the L2MSS and different components of SRLL. The indices include chi-square statistics (X2), chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (X2/df), goodness of fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), Adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), normal fit index (NFI), incremental fit index (IFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

Table 4

Selected Fit Indices for the Final Model of L2MSS and Components of SRLL

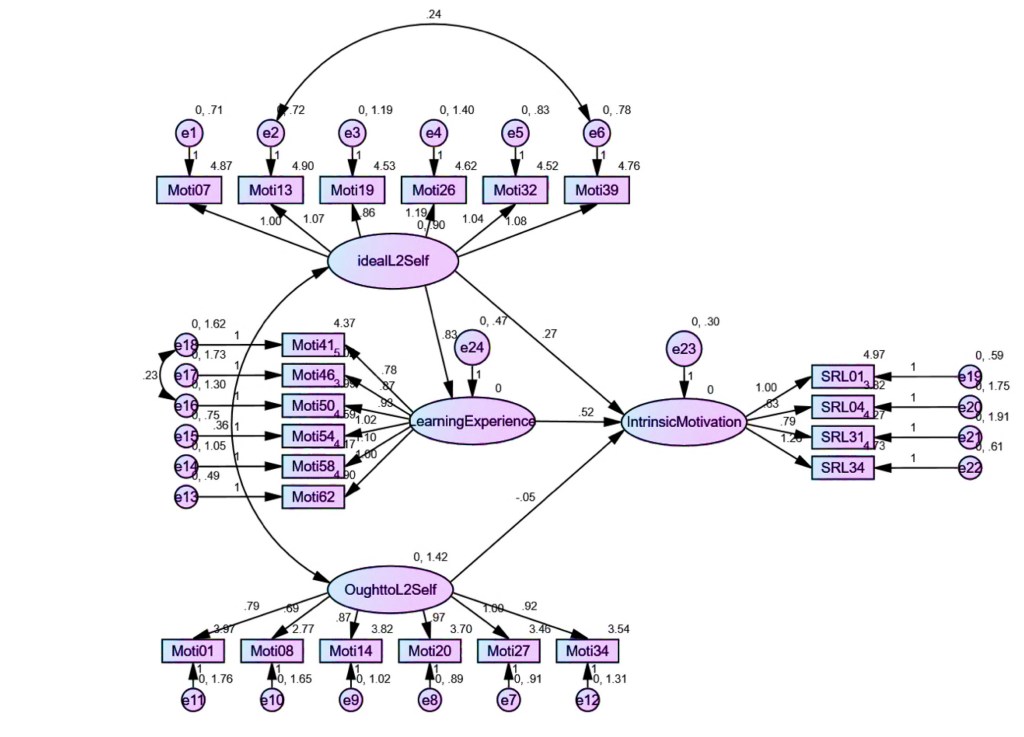

As demonstrated in Table 4, all models demonstrated excellent fit based on a range of fit indices. While the chi-square statistic was nonsignificant for any model (all p > .05), indicating potential model-data congruence, the large sample size may have limited its sensitivity in detecting misfits. Therefore, it was concluded that the model can fit the data and describe the relationships between different components of L2MSS and SRLL. Figure 2 presents the strengths of the relationships between IM and each of the three components of the L2MSS.

Figure 2

The Final Model of L2MSS and IM, a Component of SRLL

According to the figure, the motivational component of SRLL is the most robust causal relation between the English learning experience and IM. The figure displays a positive relationship between the ideal L2 self and IM. On the other hand, the effect of the ought-to L2 self on IM is negligible and statistically nonsignificant (p > .05). The results, therefore, show the robust effect of the English learning experience on the learner’s level of IM. The ideal L2 self can also contribute more to IM through the English learning experience (See Figure 2).

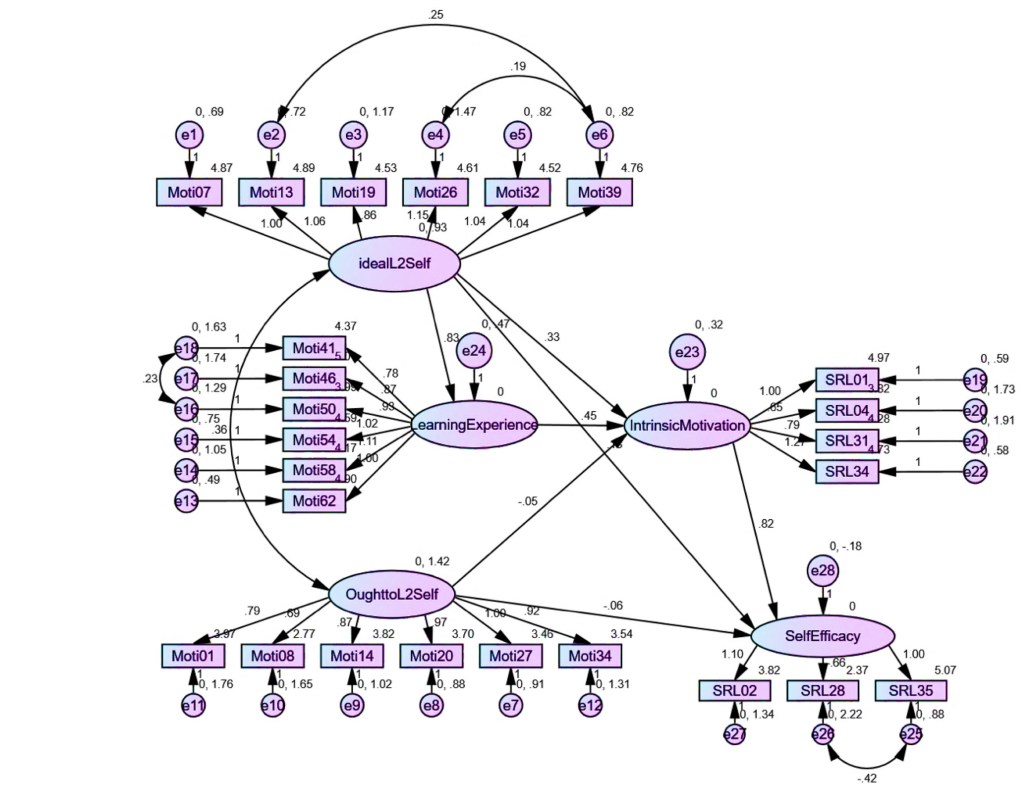

The model explored the connections between the L2MSS and self-efficacy components in the subsequent analysis stage. Figure 3 shows the strengths of causal paths between the variables in a model that can best describe the relationships. As shown in the figure, IM, primarily affected by the English learning experience and ideal L2 self, has the most substantial positive impact on self-efficacy. Although the ideal L2 self has a positive and direct effect on self-efficacy, the more significant positive effect of this variable on self-efficacy through IM is evident according to the model. The figure also indicates a small negative link between ought-to L2 self and self-efficacy. Ought-to L2 self is also negatively associated with IM and has a negligible effect on this variable (See Figure 3).

Figure 3

The Final Model of L2MSS and Self-Efficacy, a Component of SRLL

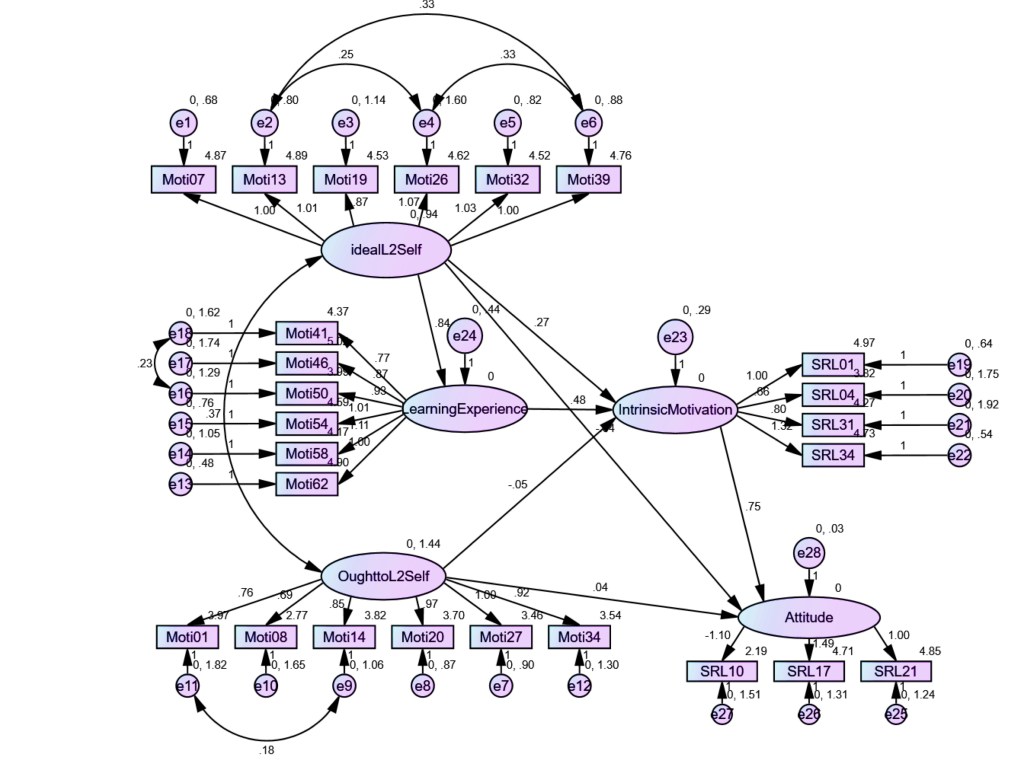

Learners’ attitudes to English learning were another component of SRLL investigated in the study. According to Figure 4, attitude, one of the components of SRLL, is strongly associated with IM and indirectly affected by the ideal L2 self. On the other hand, the values relating to other causal paths show that the effects of other components, including ought- to L2 self, are weak and nonsignificant (p>.05).

Figure 4

The Final Model of L2MSS and Attitude, a Component of SRLL

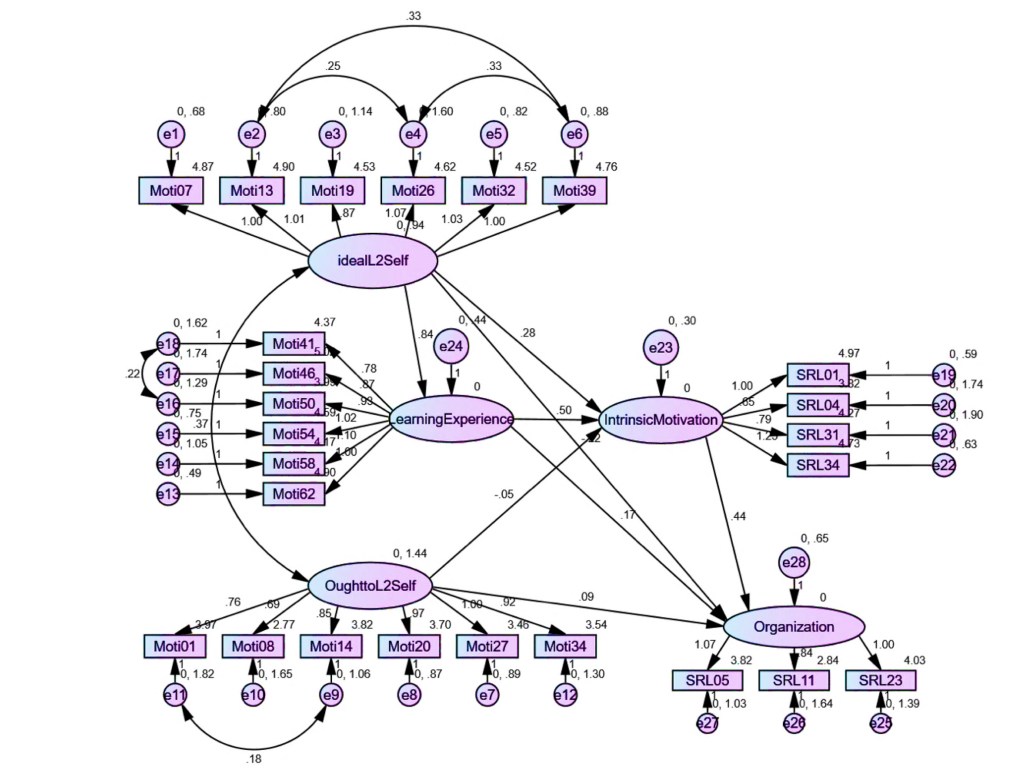

Organization was the fourth component of SRLL examined. Figure 5 reveals that the positive impact of IM on the organization is much more substantial than the slightly negative but statistically significant effect of the ideal L2 self on this variable. Ought-to L2 self and English learning experience have slightly positive and statistically significant effects on IM (p<.05). Figure 5 indicates that the ideal L2 self can make a much more significant and positive contribution to the organization when the English learning experience and IM mediate the effect.

Figure 5

The Final Model of L2MSS and Organization, a Component of SRLL

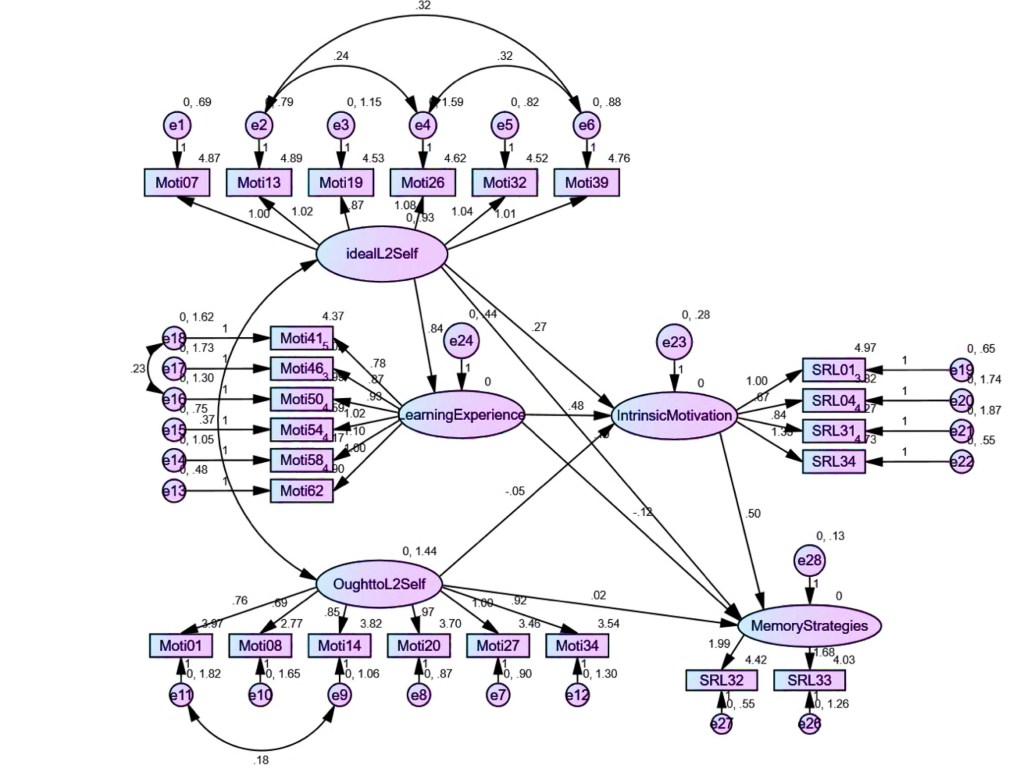

The associations between motivational variables and learners’ ability to use memory strategies were investigated next. The results revealed that, once again, the most potent path can be found from IM to memory strategies and English learning experience, which has a relatively strong relationship with IM indirectly contributing to memory strategies through this variable. The ideal L2 self can also contribute best to memory strategies through its positive effect on the English learning experience and IM. The weak negative path between the English learning experience and memory strategies reflects that the variable can substantially affect memory strategies through IM. The effects of ought-to L2 self on IM and memory strategies are very weak and statistically insignificant (p>.05) (See Figure 6).

Figure 6

The Final Model of L2MSS and Memory Strategy, a Component of SRLL

The sixth variable of SRLL was self-monitoring, which was also strongly associated with IM (See Figure 7). The figure indicates that the most potent positive effect of the ideal L2 self on self-monitoring can be found through the English learning experience and then IM. As shown in the figure, the English learning experience has a small negative effect on self-monitoring. Ought-to L2 self has a minimal and insignificant effect on IM and does not affect self-monitoring (p>.05).

Figure 7

The Final Model of L2MSS and Self-Evaluation, a Component of SRLL

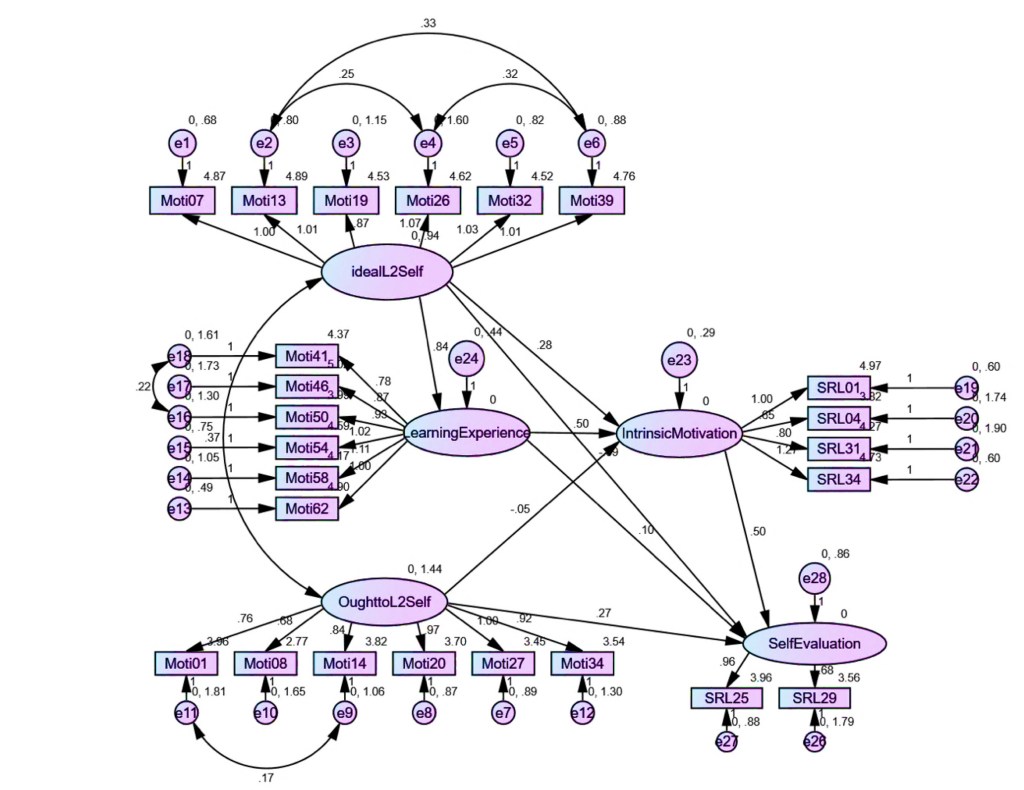

Figure 8 presents information about the contribution of the ideal L2 self, learning experience, and ought-to L2 self to IM and self-evaluation. While the direct effect of the ideal L2 self on self-evaluation is statistically insignificant, it has strong positive effects on the English learning experience and IM. Self-evaluation is moderately affected by IM. Although the ought-to L2 self is not significantly associated with IM, it has a moderate direct effect on self-evaluation.

Figure 8

The Final Model of L2MSS and Self-Monitoring, a Component of SRLL

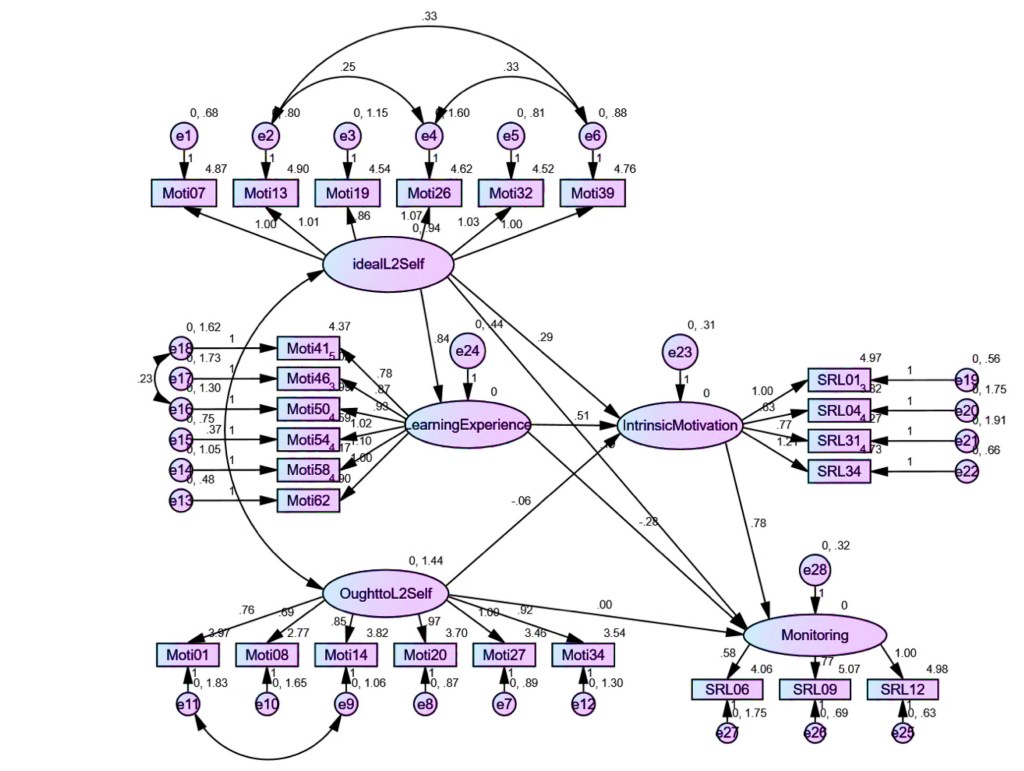

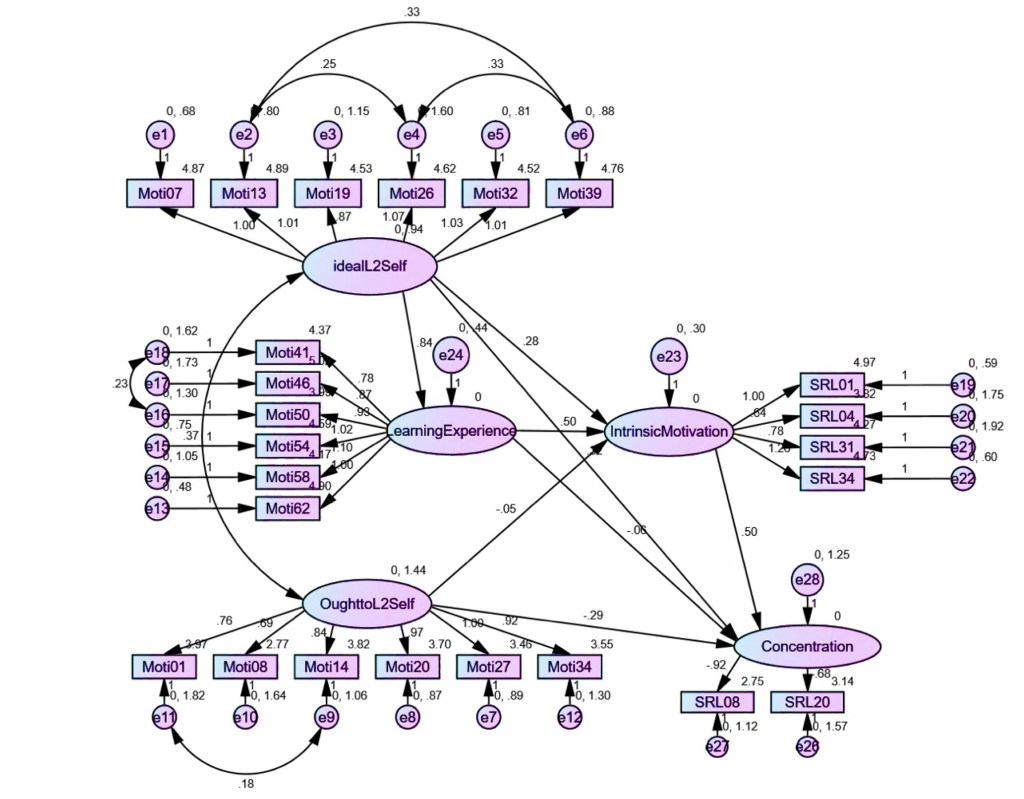

Concentration and sustained attention were the eighth variables studied. As shown in Figure 9, the most substantial connection between IM and concentration can be found. Ideal L2 self is weakly associated with this variable. While IM and the ideal L2 self positively contribute to concentration and sustain attention, the ought-to L2 self is negatively linked to this component of SRLL. All the relationships, however, are statistically significant (p<.05). The figure also indicates that the English learning experience does not have a statistically significant effect on concentration and sustained attention (See Figure 9).

Figure 9

The Final Model of L2MSS and Concentration, a Component of SRLL

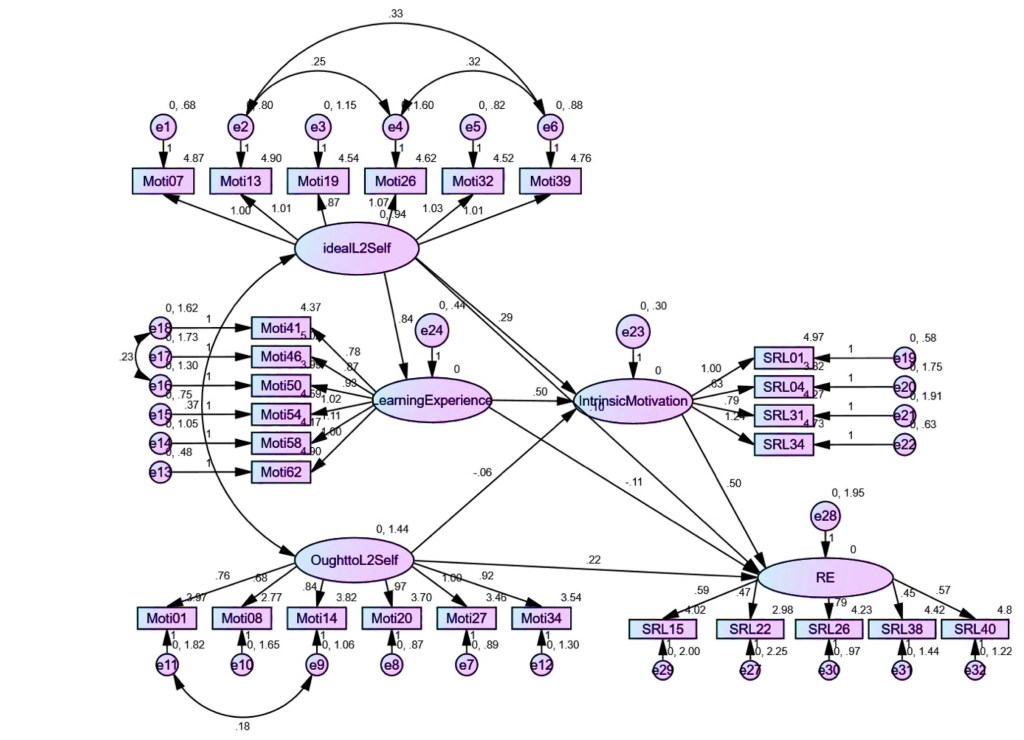

The last component of SRLL examined was the regulation of the environment. Figure 10 illustrates the degree of association between the motivational variables and this component. According to the model, the most vital link can be found between IM and the regulation of the environment, and the paths from ideal L2 self and English learning experience to the regulation of the environment are weak but statistically insignificant (p>05). The ideal L2 self also makes a statistically significant but weak contribution to IM, directly affecting the environment’s regulation. Ought-to L2 self also has a positive, statistically significant, but weak effect on the regulation of the environment (See Figure 10).

Figure 10

The Final Model of L2MSS and the Environment, a Component of SRLL

Note: RE: Regulation of the environment

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the relationships between SRLL and the constituent components of L2 motivation. The overall fit of the proposed model to the sample data was acceptable, and it was striking to see that IM consistently exhibits the most potent direct effects on the subscales associated with motivational and cognitive self-regulation (Boekaert, 1997). Moreover, it was found that two constituent elements of the L2MSS, the ideal L2 self and the English learning experience, can have the most significant effects on SRLL, mainly through IM. This finding substantiates the weight of IM in cultivating SRLL and endorses the conclusion that IM plays a vital role in SRL (Karlen, 2016; Tsuda & Nakata, 2013; Wolters et al., 1996). Furthermore, the results extend the available literature by corroborating the idea that learners can become more self-regulated if their ideal L2 self and experience of the immediate learning environment can simultaneously enhance their IM. Positive contributions of ideal L2 self and attitudes to learning English to SRLL or some aspects of it, including self-efficacy, were reported in previous studies (Roshandel et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2018). However, in the present study the effect of ideal L2 self, English learning experience and ought-to L2 self on each component of SRLL was separately examined, and appropriateness of a model which shows the strengths of the direct and indirect connections among the variables of L2MSS and SRLL was assessed.

Results of correlation tests and strengths of the direct paths indicate that the subscales of self-regulation are not similarly affected by IM. The literature supports that IM is more strongly associated with the affective constituents of SRLL, including self-efficacy and attitude, as they are all related to internal sources of affective regulation (Boekaert, 1997; Efklides, 2011). For instance, self-efficacy results align with Roshandel et al.’s (2018) findings. However, since IM has been included in the model, a much more significant influence of L2 motivation on self-efficacy can be observed. In addition, the smaller but statistically significant correlation coefficients and positive links between IM and (meta)cognitive/behavioral variables, including organization, memory strategies, self-monitoring, self-evaluation, concentration and sustained attention, and regulation of environment were reasonably expected as these variables have been theoretically associated with (meta)cognitive components (Efklides, 2011) and cognitive self-regulation (Boekaert, 1997). The strong positive correlations and paths between IM and memory strategies and strong associations between IM and self-monitoring indicate that these aspects of SRLL can be developed when learners are intrinsically motivated. Ought-to L2 self accounts for a more significant proportion of the variance contributing to organization, self-evaluation, concentration, and regulation of the environment. This finding suggests that ought-to L2 self plays a more critical role in developing SRL’s (meta)cognitive components. IM, however, remains the most significant predictor of these components.

Although ought-to L2 self was found to significantly predict some aspects of SRLL, its low path coefficients echo the findings in almost all the studies. For example, weak relationships have been reported between ought-to L2 self and intended efforts (Taguchi et al., 2009; Papi, 2010) and online self-regulation (Zheng et al., 2018). In a study conducted by Li and Zhang (2021), it was empirically shown that ought-to L2 self is a negative predictor of L2 achievement. The results of the present study have revealed that ought-to L2 self does not affect IM and has negligible direct effects on most of the constituents of SRLL. The greater correlation between ought-to L2 self and self-evaluation might be explained by the tendency of learners to assess themselves based on language ability measures valued by both their teachers and families. This process can encourage growth in instrumentality-prevention and family influence, factors that directly impact the development of an ought-to L2 self (Taguchi et al., 2009).

On the other hand, concentration and sustained attention, which are inherently dependent on learners’ mental processes, are negatively related to the ought-to L2 self. Regulation of the environment and organization are also weakly associated with the ought-to L2 self. This finding might suggest that learners willing to undertake tasks in these two areas are slightly influenced by external variables such as learning environment characteristics and others’ standards of organizing language learning. Although IM has a more significant effect on both variables, the small impact from ought-to L2 self may show that environmental control and learners’ ability to organize their learning process may also be weakly affected by external factors such as family and exams.

Conclusion

Although motivation is believed to be an integral part of SRL, studies have yet to examine its effects on the subscales of SRLL in a model that exhibits the effects of various motivational variables. The current study adds empirical evidence to the existing literature on SRL in an English class, showing that IM plays the most influential role in enhancing SRL’s affective and cognitive constituents. Therefore, it is recommended that teachers, materials developers, and policymakers prepare the grounds for SRL by raising learners’ IM. The present study’s findings suggest that the English learning experience and ideal L2 self can significantly affect SRLL through IM. One implication of this study is that curriculum developers and teachers should plan and incorporate techniques into the curriculum, such as guided visualization of the ideal L2 self, breaking down goals into actionable steps, and mentorship (e.g., peer or teacher mentorship). These techniques can foster an ideal L2 self and a positive English learning experience (Dörnyei, 2001; Dörnyei & Kubanyiova, 2014; Magid & Chan, 2012). Incorporating these strategies can, therefore, help learners become more emotionally and cognitively self-regulated, especially if they also lead to improvements in learners’ IM.

This study, along with all research, has inherent limitations. Religious and cultural values are essential in Iranian high schools. Besides, they are part of Iran’s coeducational system, which provides distinct experiences for urban and rural students. Although the results are mainly in line with those reported in other research studies in other learning environments, the fact that the respondents were selected from three high schools may limit the generalizability of the findings, as the results may have been affected by the unique characteristics of the sociocultural context. Further research is needed to investigate the issue in other educational contexts and cross-validate the findings. Also, the relationships between L2 motivation and four variables of SRLL, including locus of control orientation, planning and goal setting, effort regulation, and help seeking, could not be investigated as the reliability values were below the acceptable level. To remedy this constraint in future research endeavors and to triangulate the results, other instruments can be utilized to measure different components of SRLL in various learning environments. The findings rely on self-reported data, which may not reflect learners’ SRL behaviors. Follow-up studies can use qualitative methodology to investigate SRLL behaviors in different motivational conditions and overcome this limitation.

Notes on the Contributors

Nima ZabihiAtergeleh is a Ph.D. candidate in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) at the Islamic Azad University (IAU), Qaemshahr Branch, Iran. He is a high school English language teacher, educator, and evaluator who has taught different EFL courses since 2009. He has presented papers at national and international conferences. His main research interests are SRLL, L2MSS, language learning strategies, and teaching English. He has been an active reviewer of the RSIS journals.

Mehrshad Ahmadian is an assistant professor in TEFL at the IAU, Qaemshahr Branch, Iran. He has published articles in various national and international journals. His research interests are (critical) language teacher education, language assessment, and all four language skills.

Shaban Najafi Karimi is an assistant professor in TEFL at the IAU, Qaemshahr Branch, Iran. His main research interests include discourse analysis, materials development, strategies for developing language skills, and teacher education.

References

Abdollahzadeh, E., Amini Farsani, M., & Zandi, M. (2022). The relationship between L2 motivation and transformative engagement in academic reading among EAP learners: Implications for reading self-regulation. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 944650. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.944650

An, Z., Wang, C., Li, S., Gan, Z., & Li, H. (2021). Technology-assisted self-regulated English language learning: Associations with English language self-efficacy, English enjoyment, and learning outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 558466. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.558466

Bai, B., Shen, B., & Mei, H. (2020). Hong Kong primary students’ self-regulated writing strategy use: Influences of gender, writing proficiency, and grade level. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 65, 100839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100839

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Barnard, L., Lan, W. Y., To, Y. M., Paton, V. O., & Lai, S. L. (2009). Measuring self-regulation in online and blended learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 12(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.10.005

Boekaerts, M. (1996). Self-regulated learning at the junction of cognition and motivation. European Psychologist, 1(2), 100–112. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.1.2.100

Boekaerts, M. (1997). Self-regulated learning: A new concept embraced by researchers, policy makers, educators, teachers, and students. Learning and Instruction, 7(2), 161–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(96)00015-1

Boekaerts, M. (2011). Emotions, emotion regulation, and self-regulation of learning. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (pp. 408–425). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203839010

Borkowski, J. G., & Thorpe, P. K. (1994). Self-regulation and motivation: A life-span perspective for underachievement. In D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Self-regulation of learning and performance: Issues and educational applications (pp. 45–73). Lawrence Erlbaum. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203763353-3

Cleary, T. J., & Kitsantas, A. (2017). Motivation and self-regulated learning influences on middle school mathematics achievement. School Psychology Review, 46(1), 88–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2017.12087607

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Motivational strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667343

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9–42). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847691293-003

Dörnyei, Z., & Kubanyiova, M. (2014). Motivating learners, motivating teachers: Building vision in the language classroom. Cambridge University Press. https://nottingham-repository.worktribe.com/output/1100971

Dörnyei, Z., & Taguchi, T. (2009). Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration, and processing. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203864739

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (Eds.). (2009). Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (Vol. 36). Bristol: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847691293

Dunn, K., & Iwaniec, J. (2022). Exploring the relationship between second language learning motivation and proficiency: A latent profiling approach. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 44(4), 967-997. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263121000759

Efklides, A. (2011). Interactions of metacognition with motivation and affect in self-regulated learning: The MASRL model. Educational Psychologist, 46(1), 6-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2011.538645

Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and Motivation in Second-language Learning. Newbury House Publishers.

Greene, J. A., & Azevedo, R. (2007). A theoretical review of Winne and Hadwin’s model of self-regulated learning: New perspectives and directions. Review of Educational Research, 77(3), 334–372. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430303953

Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106-121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: a theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319

Ishida, A., Manalo, E., & Sekiyama, T. (2024). Students’ motivation to learn English: the importance of external influence on the ideal L2 self [Original Research]. Frontiers in Education, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1264624

Kadioglu, C., Uzuntiryaki, E., & Aydin, Y. Ç. (2011). Development and Validation of Self-Regulatory Strategies Scale (SRSS). Egitim ve Bilim, 36(160), 11.

Karlen, Y. (2016). Differences in students’ metacognitive strategy knowledge, motivation, and strategy use: A typology of self-regulated learners. The Journal of Educational Research, 109(3), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.942895

Khaleghizadeh, S., Pahlavannezhad, M. R., Vakilifard, A., & Kamyabi Gol, A. (2020). Validation of Persian language learning motivation questionnaireas a second language. Journal of Teaching Persian to Speakers of Other Languages, 9(20), 25-63. https://doi.org/10.30479/jtpsol.2020.9935.1421

Kim, T. Y., & Kim, Y. K. (2014). EFL students’ L2 motivational self system and self-regulation: Focusing on elementary and junior high school students in Korea. In K. Csizér & M. Magid (Eds.), The impact of self-concept on language learning (pp. 87–107). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783092383-007

Kitsantas, A., Steen, S., & Huie, F. (2009). The role of self-regulated strategies and goal orientation in predicting achievement of elementary school children. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 2(1), 65-81. https://doi.org/10.4219/jaa-2008-867

Kumar, T., Soozandehfar, S. M. A., Hashemifardnia, A., & Mombeini, R. (2023). Self vs. peer assessment activities in EFL-speaking classes: impacts on students’ self-regulated learning, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills. Language Testing in Asia, 13(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-023-00251-3

Lai, C. L., & Hwang, G. J. (2016). A self-regulated flipped classroom approach to improving students’ learning performance in a mathematics course. Computers & Education, 100, 126–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.05.006

Li, M., & Zhang, L. (2021). Tibetan CSL learners’ L2 motivational self system and L2 achievement. System, 97, 102436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102436

Magid, M., & Chan, L. (2012). Motivating English learners by helping them visualise their Ideal L2 Self: Lessons from two motivational programmes. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 6(2), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2011.614693

Markus, H., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41(9), 954. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.9.954

McCombs, B. L. (2001). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: A phenomenological view. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: Theoretical perspectives (pp. 67–123). Lawrence Erlbaum. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-3618-4_3

Mizumoto, A. (2013). Effects of self-regulated vocabulary learning process on self-efficacy. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 7(3), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2013.836206

Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 422. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00422

Papi, M. (2010). The L2 motivational self system, L2 anxiety, and motivated behavior: A structural equation modeling approach. System, 38(3), 467–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2010.06.011

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 452–502). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50043-3

Pintrich, P. R. (2004). A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Educational Psychology Review, 16, 385-407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-004-0006-x

Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.33

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J. (1993). Reliability and predictive validity of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53(3), 801-813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164493053003024

Roshandel, J., Ghonsooly, B., & Ghanizadeh, A. (2018). L2 motivational self-system and self-efficacy: A quantitative survey-based study. International Journal of Instruction, 11(1), 329–344. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2018.11123a

Şahin Kızıl, A., & Savran, Z. (2018). Assessing self-regulated learning: The case of vocabulary learning through information and communication technologies. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 31(5-6), 599-616. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1428201

Salehi, M., & Jafari, H. (2015). Development and validation of an EFL self-regulated learning questionnaire. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 33(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2015.1023503

Schmitz, B., & Wiese, B. S. (2006). New perspectives for the evaluation of training sessions in self-regulated learning: Time-series analyses of diary data. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 31(1), 64-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2005.02.002

Schunk, D. H. (2005). Self-regulated learning: The educational legacy of Paul R. Pintrich. Educational Psychologist, 40(2), 85-94. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4002_3

Schunk, D. H., and Zimmerman, B. J. (2023). Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance: Issues and Educational Applications. Erlbaum.

Seker, M. (2016). The use of self-regulation strategies by foreign language learners and its role in language achievement. Language Teaching Research, 20(5), 600–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168815578550

Stoeger, H., & Ziegler, A. (2008). Evaluation of a classroom based training to improve self-regulation in time management tasks during homework activities with fourth graders. Metacognition and Learning, 3, 207–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-008-9027-z

Su, L., Noordin, N., & Yang, D. (2023). Unraveling the Path to Success: Exploring Self-Regulated Language Learning among Chinese College EFL Learners. SAGE Open, 13(4), 21582440231218537. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231218537

Su, Y., Zheng, C., Liang, J. C., & Tsai, C. C. (2018). Examining the relationship between English language learners’ online self-regulation and their self-efficacy. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(3), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3548

Taguchi, T., Magid, M., & Papi, M. (2009). The L2 motivational self system among Japanese, Chinese and Iranian learners of English: A comparative study. Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self, 36, 66–97. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847691293-005

Teng, L. S. (2022). Explicit strategy-based instruction in L2 writing contexts: A perspective of self-regulated learning and formative assessment. Assessing Writing, 53, Article 100645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2022.100645

Tseng, W. T., Dörnyei, Z., & Schmitt, N. (2006). A new approach to assessing strategic learning: The case of self-regulation in vocabulary acquisition. Applied Linguistics, 27(1), 78–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ami046

Tsuda, A., & Nakata, Y. (2013). Exploring self-regulation in language learning: a study of Japanese high school EFL students. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 7(1), 72–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2012.686500

Winne, P. H. (2001). Self-regulated learning viewed from models of information processing. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Self-regulated learning and academic achievement (pp. 153–190). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410601032

Winne, P. H., & Hadwin, A. F. (1998). Studying as self-regulated engagement in learning. In D. J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A. C. Graesser (Eds.), Metacognition in educational theory and practice (pp. 277–304). Erlbaum.

Wolters, C. A., & Pintrich, P. R. (1998). Contextual differences in student motivation and self-regulated learning in mathematics, English, and social studies classrooms. Instructional Science, 26(1), 27-47. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003035929216

Wolters, C. A., Shirley, L. Y., & Pintrich, P. R. (1996). The relation between goal orientation and students’ motivational beliefs and self-regulated learning. Learning and Individual Differences, 8(3), 211–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1041-6080(96)90015-1

Yoon, M., Hill, J., & Kim, D. (2021). Designing supports for promoting self-regulated learning in the flipped classroom. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 33, 398–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-021-09269-z

You, C., & Dörnyei, Z. (2016). Language learning motivation in China: Results of a large-scale stratified survey. Applied Linguistics, 37(4), 495–519. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amu046

Zeidner, M., Boekaerts, M., & Pintrich, P. R. (2000). Self-regulation: Directions and challenges for future research. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 749–768). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50052-4

Zhang, R., Cheng, G., & Chen, X. (2020). Game-based self-regulated language learning: Theoretical analysis and bibliometrics. PloS ONE, 15(12), e0243827. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243827

Zhang, D., & Zhang, L. J. (2019). Metacognition and self-regulated learning (SRL) in second/foreign language teaching. In X. Gao (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 883–897). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02899-2_47

Zheng, C., Liang, J. C., Li, M., & Tsai, C. C. (2018). The relationship between English language learners’ motivation and online self-regulation: A structural equation modelling approach. System, 76, 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.05.003

Zheng, C., Liang, J. C., Yang, Y. F., & Tsai, C. C. (2016). The relationship between Chinese university students’ conceptions of language learning and their online self-regulation. System, 57, 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.01.005

Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview. Educational Psychologist, 25(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2501_2

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–40). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50031-7

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into practice, 41(2), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2

Zimmerman, B. J., & Moylan, A. R. (2009). Self-regulation: Where metacognition and motivation intersect. In D. J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A. C. Graesser (Eds.), Handbook of metacognition in education (pp. 299–315). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203876428

Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (2008). Motivation—An essential dimension of self-regulated learning. In D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Motivation and self-regulated learning (pp. 1–30). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203831076