Yaya Yao, Graduate School of Design, Kyushu University, Japan

Yimeng Jin, Graduate School of Systems Life Sciences, Kyushu University, Japan

Yao, Y., & Jin, Y. (2024). “My Japanese is blue, because it makes me blue”: Centering emotion in language practices through language mapping. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(3), 529–559. https://doi.org/10.37237/150311

Abstract

Since the social turn in applied linguistics, there has been growing interest in the role of emotion in language practices. This role is especially relevant to self-access language learning in terms of how it influences learner autonomy and motivation. With its focus on autonomy and sociality, self-access learning offers unique affordances for facilitating learner and advisor awareness of emotion in language learning. To this end, this study used an arts-based method, language mapping, for learners to express their language practices in multimodal ways. Language mapping integrates body mapping and language portraits methods to catalyze individual and group reflection anchored by embodied, emotional experiences. The researchers collaborated with a Japanese university self-access language learning center to engage seven volunteer participants in a series of two workshops. Data were gathered through participants’ language maps, narratives shared in workshops, and questionnaire responses. Findings highlight the potential of language mapping in exploring learners’ affective connections to their named languages. While mother tongues were generally portrayed as comforting, vivid, default, and unconscious, relationships to learned languages were represented through more diverse visual and verbal metaphors. Key pedagogical considerations include the impact of exemplars and group processes.

Keywords: body mapping, emotion, language portraits, language learning, self-access learning

In the past few decades, the social turn in language education and applied linguistics has paved the way for greater attention to the role of emotion in language learning and use. This does not only refer to the emotions that arise in language learning, but to the ways in which language is experienced in affective terms. Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory (1978) established how socioemotional connection is fundamental to cognition, and while many in the field have taken up this claim, an overfocus on cognition remains. While it now goes without saying that emotion plays a substantive role in language learning and learner motivation, the nature of this role is still being defined (White, 2016). Articulating the shifting, multilayered dimensions of this “elephant in the (language learning) room” is no small feat (Swain, 2013, p. 195), and a phenomenological approach can build an understanding of these dimensions in locally grounded ways.

In this vein, our study used an arts-based approach to explore how emotion influences language practices in first-person terms. We conducted workshops in collaboration with a self-access language learning center because the nature of self-access language learning (henceforth SAL) connected with the purposes of our study, given that learner autonomy, the focal concept in SAL (Mynard & Shelton-Strong, 2022), is increasingly understood in holistic terms that encompass emotion.

In this study, we innovatively combined the two arts-based methods discussed below, body mapping and language portraits, building on a new approach, language mapping, applied in one prior study (Yao, 2024). Multilingual learners were invited to explore their emotions in relation to their language practices through a series of language mapping workshops. As in the language portraits method, participants were asked to assign a color to each of their languages based on their feelings in, or towards, that language, and then color in the body according to these assigned colors. They also engaged in activities using their body maps as an anchor for visual expressions of reflections and memories.

Through this creative method, our study aimed to:

- Evaluate the efficacy of language mapping in centering emotion in language practices.

- Explore emotion in language practices as expressed in the language mapping workshops.

To further explore participants’ feelings towards their named languages, findings are presented and discussed in two separate sections, “Mother Tongue” and Language Learning, followed by a general discussion.

In summary, this study introduces language mapping as a novel arts-based methodology for exploring the emotional dimension of language practices. By delving into participant experiences in multimodal ways, this approach elucidates the ways in which metaphors illustrate the emotional dynamics that shape language practices. We recommend language mapping to self-access learning advisors and other language educators to emphasize the importance of comprehending the ways in which the affective dimensions of languaging are unique to each of us and each of our learners. Deepening this understanding will allow us to more effectively support learner development and autonomy.

Literature Review

Emotions in Language Learning

Although the distinctions between emotion, mood, and affect are contested (Blackman, 2021), for the purposes of this article, emotion is defined as a shorter, more intense, and more directed affective experience than mood, which is “relatively longer duration with more diffuse affect” (Schutz et al., 2006). Because emotion is directed towards an “object” and encompasses “relations to [that] object” (p. 344), the concept is useful in seeking to explore the nature of the learner’s affective connections to their linguistic repertoire.

Scholars such as Tassinari (2016) and Moriya (2019) advocate for greater attention to emotion in SAL. Similarly, Yamashita (2015) highlights the need for meta-affective strategies in the field, referring to techniques that allow SAL learners (and advisors) to reflect on their emotional experiences of, and relationships to, their language practices and repertoires. This reflection can build their capacities to make autonomous choices in their learning journeys. Scaffolding these strategies would support increasingly agentic understandings of affect and emotion as potentially powerful psychological resources (White, 2016). These resources could be called upon to facilitate their understandings of their languaging practices in relation to broader sociopolitical dynamics, which in turn could support their learning processes in working towards concrete learning goals.

Such calls for greater attention to affect and subjectivity in SAL recognize the challenges this poses to advisors and educators, who might be daunted by the skills required to address learners’ psychological needs (Tassinari & Ciekanski, 2013). Also, it can be difficult for learners to verbalize their feelings in relation to their linguistic practices and experiences in the advising context, especially if their proficiency in the language of instruction/advising is low.

Art-based Methods in Language Learning

Arts-based methods can respond to these challenges by offering accessible, multimodal approaches to meta-affective reflection. Through the arts, individuals can reflect on their experiences in flexible, embodied ways, transcending linguistic barriers (Mohamed, 2021). This facilitates transmodal, nonverbal, and open-ended expression, fostering empathy (Eschenauer, 2018) and facilitating social connection. In SAL, visual meta-affective reflection methods such as the Wheel of Language Learning (Kato & Yamashita, 2012; Shelton-Strong & Mynard, 2018) have proved to be powerful tools accessible to a range of proficiency levels.

Body mapping is one visual method that is widely used in health and labor advocacy. Originating from Jane Solomon’s work with women living with HIV in South Africa, body mapping is a visual method in which participants create life-sized outlines of their bodies, which then become a canvas through which they explore their lived experiences (Gastaldo et al., 2012). Furthermore, arts-based methods have proven to be impactful in exploring participants’ emotions in relation to their language practices. Language portraits (or plurilingual portraits), for example, which prompt participants to assign a color to each language they identify with, is a popular method for understanding how individuals perceive their language practices and identities (Kusters & Meulder, 2019).

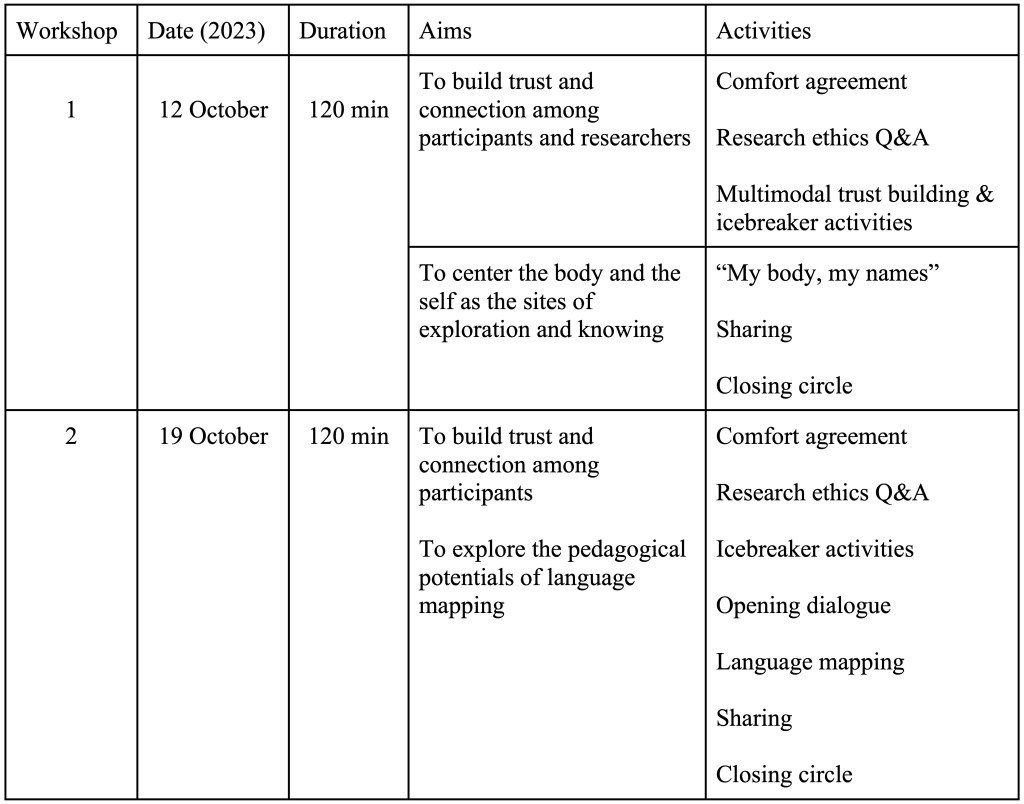

Methods

A series of two workshops, both attended by the same group of participants, was conducted for the study. Workshops were 120 minutes each, and the series was conducted through a university self-access language learning center. Building off a prior collaboration, we approached the center with the proposal for collaboration, and the center agreed to sponsor the workshops and provide logistical and in-kind support. The center had been interested in diversifying its offerings to service users to include more creative and arts-oriented activities. One of the researchers, Yaya, had conducted a well-received workshop series on similar themes at the center earlier in the year, so we had already built a certain level of trust with the center staff.

The workshops applied a hybrid approach we refer to as language mapping (Yao, 2024). It is an integration of language portraits (Krumm, 2007) and body mapping (Solomon, 2007). Language portraits are “a visual and verbal representation of linguistic experience, and linguistic resources” (Busch, 2012, p. 1). In this method, the silhouette of a body is distributed on a regular-sized sheet of paper. Participants are asked to a) select colors for each of their named languages based on their feelings towards each language, and b) color in (or around) the body according to these colors. Krumm and Jenkins first applied this method to study multilingual children’s language awareness, publishing the work in German (Krumm, 2011). Since then, the method has been used in diverse educational settings as it helps us “to see languages as embodied, experienced and historically lived” (Kusters & De Meulder, 2019, p. 2). Busch (2012) argues that language portraits are effective in studying the notion of heteroglossic repertoire as informed by a poststructuralist view of language. Integrating this method with body mapping brings this embodied, historicized perspective to the next level.

Body mapping is an arts-based methodology through which participants craft a visual representation of a life-sized body–which can represent an individual or collective self–and use it to generate and share stories, memories, and experiences (Gastaldo et al., 2018). It can be implemented individually or in groups. In this study, participants created life-sized silhouettes of their own bodies with the help of a partner or facilitator, who traced their body, in a pose of their choice, onto mural paper. Initially used by Solomon (2007) as a participatory method through which to identify and advocate for the health needs of HIV-positive women in South Africa, it has since been taken up in health, social work, and education.

When we make a body-map, we outline the shape of the human body as a starting point so that we can make life-size pictures of ourselves. Our body-maps include everything that we feel is most important about ourselves (Solomon, 2007, pp. 2–3).

Body mapping has now developed into “a methodology (no longer a single method) that comprises participatory, narrative, and arts-based components” (Gastaldo et al., 2018, p. 14). Gastaldo et al. (2018) present the term Body Mapping Storytelling to emphasize the narrative nature of the methodology.

In the first workshop, after creating the life-sized outlines of their language maps, participants wrote the many names they go by on their maps, in any language, and discussed these in pairs. Through this activity, participants introduced their names in different languages as connected to aspects of their identity. In the following week’s workshop, participants were asked to assign a color to each named language based on their feelings towards them, and to then fill in their bodies using these colors, relating their languages to different areas of their bodies in personal ways.

Table 1

Workshops Process

Figure 1

Examples of Participants’ Language Mapping During the Workshop

Participants

Seven volunteers, all international students at a Japanese university, participated in a series of two workshops in October 2023. Participants self-selected in response to a poster distributed through the center’s and researchers’ online networks. Each participant received a ¥2000 gift card for participating in both workshops, and these were distributed at the second workshop. Workshops were facilitated by the two researchers and received logistical assistance from center staff. The table below outlines participant information collected at the first workshop.

Participants were virtually all graduate students, as most of the international students at the university are graduate students. It could also be related to the nature of our professional and student networks, as doctoral researchers ourselves. It could be argued that this predominance of international graduate students with high levels of proficiency in English might make findings irrelevant to English language learners. These students are also uniquely attuned to questions of language as related to nationality and ethnicity due to their experiences as either visiting students or migrants to Japan. While these characteristics can certainly be understood as limitations, we believe that the findings still indicate the potentials of the method in culturally hybrid, autonomy-oriented, and socially oriented spaces such as self-access learning.

Table 2

Participant Information

The Ethics Committee of [redacted for review process] approved the study. Informed consent, which included a no-risk statement and rights protection, was gathered from participants and was discussed at the beginning, end, and halfway into the process to deepen understanding and a sense of participant autonomy throughout.

Data Sources

The primary study data were participants’ explanations of their language maps. They provided these explanations verbally in the workshops, with a dialogic dimension as others asked questions, all of which were audio recorded and transcribed. Participants’ language maps were referred to, to better understand their explanations. We also gathered participant responses to an open-ended survey after the workshops, along with informal dialogue following the workshops and researcher observation journals. Observational data in the form of video recordings of the workshops was also collected.

Data Analysis

We applied reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2019) to develop an understanding of the data rooted in our research questions, the literature, and our own positionalities and reflexivity connected to language and identity. Reflexive thematic analysis is an approach to thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) that emphasizes the creativity of theme generation and the necessarily subjective nature of analysis, “with researcher subjectivity understood as a resource” (Braun & Clarke, 2019, p. 591) in an interpretive creative process. In this vein, we take a moment here to discuss our own positionalities to offer some background as to the nature of our interaction with the data. We do so in the first person to highlight the situated and emic nature of our inquiry.

Yimeng: I was born and educated in mainland China through my bachelor’s degree and started my translingual journey at the age of 23 when I relocated to Japan. The transition from exclusively using Mandarin Chinese to incorporating English, Japanese, and Mandarin Chinese into my daily communications was challenging yet enlightening. I found that different languages could elicit distinct sides of my identity. It piqued my curiosity about how other multilingual individuals navigate and perceive their identities across different languages.

Yaya: I am a second-generation, middle-class, queer cisgender woman born and raised in Tkaronto (colonially, Toronto) of Han Chinese descent. I grew up in a multilingual household, school context, and society, in a mix of Mandarin, Fujianese, Cantonese, English, and French. Only in translanguaging poetry did I feel I could truly express the fullness of my voice. These formative experiences are different from this study’s participants in the sense that they were born and raised in contexts in which they were part of the ethnic and linguistic majority.

Awareness of our own positionalities allowed us to reflect on the situated nature of participants’ relationships to and embodied experiences of their languaging practices. Generating themes in this way allowed us to recognize the overlaps and divergences from our own experiences as multilinguals, and the great diversity within the group. The two of us first inductively coded separate sets of transcripts of participants’ verbal discussions of their language maps. After this, we came together to identify and discuss the commonalities and differences between our codes, revising the codes as we made increasingly complex connections between the data sets. We then developed themes in an iterative process of analysis and writing.

As such, although we used the visual data as a reference point to better understand the participant’s discussion of their creation, we focused on the verbal data as participants’ emic interpretations of their language maps. This reflected our emancipatory stance in wanting to recognize participants as “co-producers of knowledge” (Parker et al., 2017, p. 2) rather than impose our interpretations of their creations. In this process, we paid special attention to the metaphorical elements of their interpretations, their discussions, and rationale around color, symbol, and placement on the body.

Findings

“Mother Tongue”

As researchers, we opted to use the terms “first language(s),” “home languages,” and “adopted languages” to refer to the languages in participants’ repertoires and our own. However, when presenting and discussing their work, virtually all participants referred to their first languages as “mother tongues.” While we mirrored these terms in our interactions, we negotiated a certain amount of discomfort with them. The concept of the mother tongue, at its worst, can flatten the complexities of ethnicity, genotype, language, and nationality (Rampton, 1990), not to mention uphold heteronormative conceptualizations of motherhood. Explaining that these assumptions have been roundly debunked, Rampton (1990) urges language educators to opt out of the “clutter” of the term by applying terms that outline the sociopolitical aspects of language that the term refers to: language expertise, language inheritance, and language affiliation. Ultimately, though, we chose to reflect the language used by participants to honor their understandings of and connections to the term.

Colors of the Mother Tongue as Vivid or Default

Representations of a language described as a mother tongue were illustrated in virtually all the participants’ body maps. Some participants chose vivid colors such as red or orange for their mother tongues, reflecting a sense of intimacy and essentiality. Wesley, for example, chose red for one of his mother tongues, Indonesian, referencing the color of blood, while his other, Javanese, he represented as green, which is his mother’s favorite color. With these, he drew network lines throughout the body to illustrate their essentiality as roots. Rose explained her choice of orange for Mandarin, her first language, because it “warms me up,” and because of its depth of symbolic meaning. Remarkably, the use of such vivid colors to signify the positive emotions and identities attached to the mother tongue echoes findings from previous studies, where language portraits were analyzed. Mohamed’s (2021) study saw a group of preschool children tend to select bright colors for their first language, and Coffey’s (2015) preservice teacher participants generally chose either vivid colors for their mother tongues, to illustrate the richness of their experience in their mother tongue(s), or neutral colors, to evoke the unconscious and innate nature of their relationships to them.

In this vein, Ruth chose white to represent her mother tongue, as she felt it to be a neutral color that she generally took for granted, as such not at the forefront of her consciousness.

Mandarin is my mother tongue, so it’s actually white because it’s kind of like a default color for me, and also white reflects all the colors. So when I speak Mandarin, it will show all of my colors. (personal communication, October 19, 2023)

Jorge used blue for the same reason, “because I don’t have to think to speak Spanish” (personal communication, October 19, 2023). The representation of the mother tongue as a neutral or default color is echoed by language maps created by Japanese high school students in a related study (Yao, 2024), along with the Coffey (2015) study. In a similar vein, Cecilia chose black to represent English, which she considers to be one aspect of her mother tongue (discussed below). She did so for a similar reason as Ruth: “It’s kind of just always there, so it’s like my default.” She adds another dimension, though, stating that she chose black to represent the fact that for her, “It’s very academic.”

In the realm of inner emotions, some participants exhibited a unique approach, using colors not only to express their own feelings, but also to symbolize individuals or objects with whom they share emotional connections. This is evident in Wesley’s choices for Indonesian and Javanese. For Indonesian, he selected the vibrant hue of orange, a color associated with fond memories from his childhood. In the case of Javanese, Wesley opted for green, a color linked to his mother’s preferences, thus reflecting a sentimental tie to his familial relationships.

Placement of the Mother Tongue as Foundation

The conceptualization of the mother tongue as a center, or foundation, was conveyed by many participants, who often placed the mother tongue in the trunk or center of the body, or near the heart. Rose, for example, placed the mother tongue at their belly, relating this choice to the Chinese medicine concept of the dan tian (in the sacral area) as the energetic center of the body. Ana similarly located her mother tongue in the belly, associating it with the sensation of being tickled and then to her inner world as “a rainforest with mainly Spanish” (personal communication, October 19, 2023). The image of the rainforest could connect to a complexity theory conceptualization of language learning in which linguistic development is a uniquely individual “wild garden,” as Virginia Rojas describes it (personal communication, February 17, 2017) rather than a linear model of progression.

The idea of the mother tongue as center is echoed in Wesley’s portrayal of his mother tongues of Indonesian and Javanese as a network of lines resembling roots or veins running through his body. He described these as integral because they connected to his sense of spirituality, fundamental to his body because “It’s my faith” (personal communication, October 19, 2024).

Besides the belly, Ana also situated her mother tongue in her legs, as the foundation of her body; what it rests on. She said, “My heart is in Spanish,” indicating an existential belonging in the mother tongue. This idea of the legs as foundational was echoed by Jorge, whose first language is also Spanish. For others, though, situating a language or idea in the legs was a sign that it was less important or well-regarded. Cecilia, for example, placed the Filipino language on her feet, explaining, “[It’s] just there.” She did not notice or connect to her feet much, which mirrored her relationship to the language. Cecilia explained that as a person of Chinese ancestry in the Philippines, she felt a stronger connection to Chinese. She located both Chinese and English, which she feels “better at,” in the trunk of the body.

We thus see differences in symbolic understandings of the various parts of the body, which may be connected in culture, although this link is unclear. Either way, these placements and the reasonings behind them allow us to better comprehend the nature of the individual’s relationships to their languages.

Translanguaging as Mother Tongue

As discussed above, the notion of a mother tongue can lend itself to an oversimplification of an individual or group’s linguistic roots as directly connected to heredity and lineage. This in turn is often instrumentalized for nationalist, raciolinguistic objectives that connect to native speakerist (Holliday, 2006) ideals. One participant, however, did not refer to a mother tongue, and her lived experience inherently challenges this notion.

Instead of referring to the languages of her country, ethnic group, or education as home, Cecilia referred to what could be described as a translanguaging (García, 2009) space as the one in which she felt the greatest belonging for her. This would be a space in which she could freely mix the three languages in which she feels most at home–English, French, and Japanese. She explained, “It would be easier for me if I could find somebody who speaks all three so I can just switch back and forth” (personal communication, October 19, 2023). Growing up in the plurilingual context of the Philippines, her sense of belonging in the Filipino language was lessened by her ethnic identity as a Filipino Chinese, in her words. Educated in Mandarin Chinese and English, she associated both with rules and study, while French was a language that she was drawn to and learned out of interest, rather than for instrumental goals. This sense of autonomy surrounding French, along with Japanese as the language of her adopted country, might partly explain the sense of belonging she feels in these languages, along with English.

Language Learning Materials that Match the Learner

Interest and Necessity

Participants in our study displayed diverse and often positive emotions in their interactions with languages learned out of interest. These languages were portrayed with a rich spectrum of colors, representing varied emotions. Orange conveyed vibrancy, pink, love and intimate relationships, and green, orange, and pink the feelings evoked by natural landscapes. Grey was used to represent boredom, as discussed below.

Another example of how participants use colors to express their emotions or impressions towards a learned language could be seen when examining representations of the workshop’s shared language, English. It was predominantly represented as blue or black, which some explained they used to denote its professional and academic attributes. Ana associated blue with English to represent its power in professional settings. Wesley, using the same color, chose it to signify the color of air, using this as a metaphor for the expansive (or perhaps expansionist) and international nature of English, and emphasizing its essentiality in daily life.

Participants also expressed ideas connected to interest in chosen languages through the placement of the colors. As international students opting to study in Japan, Jorge and Ana placed Japanese in their mouths, while Wesley placed Japanese in his head, both done to illustrate the effort invested in studying the language. Ana and Rose extended the metaphor to their legs, connecting them to a sense of exploration, mobility, and flexibility.

The interpretation of the hands in language mapping emerges as an intriguing feature. Jorge, Cecilia, and Rose located certain languages on their hands to signify a choice to pursue these out of interest. “It’s the language that I picked for myself” (personal communication, October 19, 2023), Jorge stated.

In contrast to languages learned out of interest, a few participants discussed languages learned out of necessity. Ana, who expressed a dislike of English, nonetheless placed it on her mouth and stomach, the former representing her frequent use of the language, and the latter symbolizing the pressure that she feels when doing so. Residing temporarily in Japan, Ruth expressed her lack of enjoyment in learning Japanese by associating it with blue, stating, “Speaking Japanese makes me blue” (personal communication, October 19, 2023). The blue of Japanese is placed on her non-dominant hand, which here conveys the fact that when speaking the language, she employs more gestures as a strategy to compensate for her limited vocabulary.

Language Learning Materials that Match the Learner

Ruth’s experience of learning German highlights the impact of materials on foreign language learning. With a longstanding plan to study in Germany, Ruth’s interest in life there was genuine, and she had been devoting ongoing efforts to learning the language. However, she struggled to find German TV programs that resonated with her preferences, making her German learning journey more challenging and contributing to her perception of the language as boring and stiff. Her fluency in English, in contrast, for instance, was achieved through repeated viewings of Friends, one of her favorite TV shows. Here, it seems that cultural differences posed a barrier, ultimately impacting her German learning experience. As a result, her eventual perception of the language as uninteresting and obscure is rendered by the color gray. Ruth’s explanation underscores a key aspect of her language-learning approach and emphasizes the role of popular culture as language-learning materials.

Discussion

“Mother Tongue” Discussion

The language mapping process surfaced some key ideas about the anchoring effect of first language(s) on the lives of participants. While the concept of first languages/mother tongues as foundational is obviously not original, the ways in which participants visualized and verbalized their relationships to these tongues through language mapping offer insights into their unique affective languaging worlds. Such insights would certainly be of help to an advisor attempting to support them on their language development journeys.

In this endeavor, exploring what exactly the mother tongue evokes in an individual can be volatile territory. While for many, it might evoke belonging and comfort, for others, it might inspire a sense of ambivalence at best. As Moore (2023) discusses in his theorizing on linguistic dissociation, people who have experienced trauma in a certain named language may consciously or unconsciously gravitate to another. They might also be seeking to explore facets of themselves, such as LGBTQIA+ identities, that they have experienced as a source of conflict in their formative language (Eguchi, 2014; Moore, 2023).

Finally, for some, the mother tongue may not be the stable entity that individuals often feel pressured to embrace according to raciolinguistic logic (Rosa & Flores, 2017), and/or for any number of factors related to country of birth, ethnicity, nationality, and so on. Cecilia’s articulation of a translingual space involving English, French, and Japanese as her mother tongue was one that she came to realize through the language mapping process. While on some level this might be a liberating realization, it is one in which she feels some loneliness. Who, she asked, could she find to talk to in this tongue, an expression of her linguistic repertoire in these three named languages? Of these, English is the only one she learned in her childhood, and it is also the only one widely spoken in her country of birth.

Cecilia’s experience could be understood as a concrete example of Bhaba’s notion of cultural hybridity (1998) and seems to go beyond it. As all tongues and linguistic identities, it is layered with aspects of class that shape access to education and transnational mobility, making an area ripe for exploration in connection to learner autonomy. SAL is well-positioned to respond to the need for culturally hybrid third spaces (Bhaba, 1998), which connects to Li Wei’s conceptualization of the language classroom as a translanguaging space (2011) in which creativity and criticality are key tenets. Hamman’s critical translanguaging space (2018) is a development on this concept, outlining the ways in which translanguaging spaces must work to amplify and celebrate the intersectional, conventionally marginalized experiences of multilinguals who may not relate to monolithic notions of mother tongue or homeland.

Language Learning Discussion

Learning and using a new language entail a major investment of time and emotional labor, and as such the question of motivation has been heavily theorized. Gardner and Lambert (1972) distinguish between two types of motivation: integrative and instrumental. Integrative motivation, rooted in a desire to connect with target language communit(ies) and culture(s), fosters deeper learner engagement and personal interest (Saville-Troike, 2006). In contrast, instrumental motivation is driven by practical concerns such as career advancement or academic requirements. Both types of motivation could be said to be observed in participants’ responses. Although this division has been critiqued as being overly simplistic, some participants made distinctions between considerations that were integrative versus instrumental quite directly. The visual and narrative data provide insights into the emotional nuances of these differences in ways that would facilitate the design of more holistically oriented SAL strategies.

Ruth’s experience with German underscores the significance of culturally and generationally relevant language learning materials. Ryan and Deci’s basic psychological needs theory, as a facet of self-determination theory (2000), argues that people experience intrinsic motivation when three needs are met: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Although controversy over the distinctions between intrinsic/extrinsic versus integrative/instrumental motivation persists, there is a clear connection between relatedness as a psychological need and integrative motivation. The findings highlight the importance of aligning materials, both formal and informal, with learner preferences. Many find greater motivation in response to content that resonates with their background, interests, and global pop culture trends, and this content is often connected to online communities that can foster a sense of relatedness.

As mentioned above, integrative motivation fosters deeper learner engagement and interest than instrumental (Saville-Troike, 2006). Materials play an important role in this, helping them achieve positive affect (Tomlinson, 2013). As Tomlinson notes, this could be seen as especially the case in self-access learning, as materials should scaffold the learner toward becoming less reliant on materials (2010). Tomlinson asserts that self-access materials should in fact be “access-self” materials (2010, p. 79): materials that engage the learner as a whole person, in “humanistic” and practical terms. As Ruth was not able to locate “access-self” materials in her self-directed German study, she struggled to sustain motivation. This indicates that self-access learning could benefit from a greater focus on connecting learners to appropriate and relevant access-self materials, especially in the digital age. For example, many learners enjoy studying Japanese by watching anime (Shintaku, 2022). Catering to youth culture, and offering narratives that seem to transcend cultural differences, it offers a more accessible and entertaining learning pathway. Similar dynamics can be seen with the global explosion of Korean pop culture. Autonomous learners frequently express a preference for learning through K-pop or K-drama (Kriukova, 2022). The musical genre not only serves as an engaging medium for learning but also aligns with the international appeal of Korean pop culture (Chan & Chi, 2011). In contrast, the Japanese comedy genre of manzai or Korean trot music, which are associated with older generations, could pose challenges for learners without a deep understanding of the countries’ cultural nuances. To capitalize on the diverse forms of content now readily available online and otherwise, SAL can continue enhance its role by guiding learners towards current materials that are optimally challenging and engaging (Domínguez-Gaona et al., 2012).

As social media fuels powerful youth-led fan communities, SAL could work to leverage the “digital intimacy” (Thompson cited in Thomas & Stornaiuolo, 2016, p. 320) that online communities provide to foster integrative motivation, or, in the SDT framework, a sense of relatedness. Facilitating learner engagement in these venues could go hand in hand with working to foster critical digital literacy. Many fan communities, for example, are platforms for members to share fan fiction and fan art: re-mixed visions of beloved texts that often “bend” or re-story them in ways that “reimagin[e] stories from nondominant, marginalized, or silenced perspectives” (Thomas & Stornaiuolo, 2016, p. 315). Racebending and queerbending are common examples of this phenomenon, and the ways in which online communities invite this engagement are surely examples of access-self materials.

Pedagogical Considerations

Use of Exemplars

The research has also yielded valuable pedagogical reflections, the first of which concerns the influence of model texts, or exemplars. This influence became evident in the first phase of the language mapping process, in which participants were asked to brainstorm the names and nicknames that they are addressed by, in any language, onto their bodies. One researcher casually illustrated the idea with an example; she said she would put the names she disliked on her feet. This example significantly influenced three of the seven participants, who incorporated this idea in their own language maps. However, as the workshop progressed, participants demonstrated a capacity to transcend the initial model and offered diverse approaches to language mapping. Ana eventually used the feet to represent traveling and dancing, and Luna located Spanish in parts of her legs because she enjoys salsa dancing. Rose used the feet to represent flexibility, and Wesley expressed a clear shift in thinking: “I put the names [that people call me that] I don’t like on the bottom, before. But after that, I think the bottom part is still an important part of my body, so I need to put the names that I don’t like outside my body” (personal communication, October 19, 2023).

This phenomenon underscores the complexity surrounding the use of examples in guiding creative thinking. While examples offer efficient and concrete demonstrations, they may inadvertently restrict independent ideation. The questions of whether, when, and what kind of examples to provide demand careful consideration in the context of guiding creative thinking.

Impact of Pedagogical Co-creation

Another salient reflection pertains to participants’ co-creative process. Interest in co-created learning and teaching has been rising in recent years (Cook-Sather et al., 2018; Mercer-Mapstone et al., 2017; Schmied et al., 2024). It emphasizes the idea of “learners as partners” rather than passive participants in the creative learning process. Co-creation has been suggested to have significant influence on learner engagement and autonomy (Bovill, 2020; Kaminskiene & Khetsuriani, 2019). As such, the potential of co-creative pedagogy is highly relevant to SAL (Kimura, 2014).

In the post-workshop questionnaire, virtually all the participants emphasized the opportunity to hear and discuss others’ perspectives in a nonhierarchical way as the key benefit of the process. The sharing of body maps led to many instances of co-created understanding, notably exemplified by Jorge’s concept that the hand represents autonomous choice. Other participants not only adopted this idea but also engaged in collaborative elaboration; some of them added dimensions such as strength and freedom to the concept of hand, and some of them started to refer more to their active choices, which had not previously been mentioned. This dynamic showcases an ideal form of co-creation where individuals contribute diverse perspectives and build upon each other’s ideas.

There were various points throughout the process at which participants shared in pairs or small groups about their creative choices around color and placement of their languages. This sharing could have led to the similarities observed in their final language maps. When it comes to expressing internal feelings towards languages, for example, participants had an agreement associating colors such as orange with creativity and vividness, green with relaxation, and red or pink with love. Another notable commonality is that participants used colors to express not only their feelings but also their relationships with individuals or objects connected to the languages: Wesley used orange for his chosen language, Japanese, the color he associated with fond memories from his childhood. In the case of Javanese, he opted for green, his mother’s favorite, reflecting a sentimental tie to his familial relationships and the inseparability of the language from this formative connection. Similarly, Ana and Luna infused cultural and sensory elements into their choices for Japanese. Ana selected orange, representing autumn leaves, while Luna opted for pink, signifying Japan’s iconic cherry blossoms. These commonalities and divergences could offer a jumping-off point for dialogues that could build the empathy so critical to the development of trusting learning communities and advisor-advisee relationships.

Ana’s experience further illustrates the impact of collaborative learning, as she gained profound insights from other participants’ presentations. Her realization that she had never considered choosing her own name and that someone should have informed her about this possibility exemplifies the transformative power of co-creation. She said:

I don’t like my name, first, ’cause it was chosen for me, and I didn’t know that I could pick a name… Somebody should tell us about it… it made me think that I don’t have a name for me. I know that I have identities, but I don’t have a name for me, so I don’t know what that means. (personal communication, October 19, 2023)

Participants also expressed a strong sense of connectedness through this collaborative process, emphasizing the depth of impact co-creation had on their collective experience. As Wesley said, “I was surprised that it’s like we are making a new community, sharing everything” (personal communication, October 19, 2023). We contend that this non-hierarchical collaborative approach, which has great potential for facilitating meaningful engagement and relational reflection, is an essential element of translingual arts-based approaches.

Conclusion

The overemphasis on cognition has tended to limit learning and relationship-building in self-access settings (Tassinari, 2016). This paper has proposed an arts-based approach to support SAL learners and advisors to holistically reflect on our unique affective relationships to our named languages. Language mapping as a method facilitates such reflection given its open-ended, transmodal, and iterative nature. This approach centers marginalized ways of knowing and being by highlighting the individual’s embodied emotionality in the process of navigating the sociocultural dynamics of languaging and language learning. As discussed above, participants expressed diverse perceptions and emotions through language mapping, connecting reflections to mother tongues or learned languages. The colors associated with each named language serve as an entry point through which to understand the emotional worlds represented by each.

Of course, language mapping is just one example of a (co-creative) process that can build affective reflexivity, in turn fostering learner autonomy. Many arts-based approaches offer the key advantage of fostering a sense of community (Tumanyan & Huuki, 2020). Nurtured by non-hierarchical, collaborative creative process, participants are able to take different perspectives and reflect on their experiences in novel ways, responding to and bouncing off each other’s ideas to develop common language. The process of co-creating a common language is inherently autonomy-building, as it involves participants as “co-producers of knowledge” (Parker et al., 2017). In this study, this common language allowed participants to convey deeper layers of experience over time, which is particularly relevant within self-access learning communities in which advisees and advisors often come from diverse linguistic backgrounds and experiences.

A co-constructed language through which to communicate across differences could have a great impact on the nature of advising in self-access. Relationships to our languages are shaped by sociocultural dynamics, so to serve students effectively, “advisors need more holistic understanding of advisees’ emotionality” (Moriya, 2019, p. 83). Moriya discusses how “emotions are not inner feelings but what we respond to and how we symbolize it,” which “indicates that emotion is socioculturally constructed” (2019, p. 80). The intertwined nature of emotion and cognition means that the dynamics between affect and language practices are highly personal and situated. As such, paths to increasing autonomy are shaped by learners’ intersectional (Crenshaw, 1989) social locations in interaction with their sociocultural contexts. Arts-based approaches such as language mapping have the potential to synthesize and express these complexities in ways that invite curiosity and connection. For example, the creative artefacts of learner-created language maps can offer a touchstone through which to refer back to a specific affective moment in the learner’s learning journey. As a self-made, holistic benchmark that reflects what is important to the learner, the potential for autonomy- and sociality-building is great.

The potential for future research to explore the effective application of such a creative approach and similar ones should be highlighted. For example, how might language mapping be used to deepen advisors’ understandings of learners’ perceptions of their language development to date, in one-to-one settings? Body mapping has been used for health needs assessment in one-to-one settings to protect confidentiality (Gastaldo et al., 2018); what are the possibilities for this method in the context of advising? Also, how might language mapping be used to cultivate a greater sense of community and solidarity between students, and between students and advisors? There are myriad challenges in fostering trusting, prosocial relations between diverse and transient service users in a “social learning space” such as a self-access center. In such a “liminal” space, users may paradoxically experience both “anxiety and possibility,” and “a sense of displacement and discomfort” (Hooper, 2023, p. 59). In this context, language mapping and other arts-based methods could offer an accessible and engaging means to alleviate social and linguistic anxieties, shifting the focus away from proficiency and toward open-ended creative process.

In addition, how might collective arts-based processes be activated to foster non-hierarchical relations between those interpellated as advisor and advisee, recasting all stakeholders in the self-access center as language learners on unique developmental journeys?

Also, the sense that the mother tongue can, in fact, be a mix of languages reflecting the individual’s unique holistic repertoire, is ripe for further research in the field of self-access. Indeed, self-access learning can be at the leading edge of the creation of “translanguaging spaces” (Li Wei, 2011). Li Wei explains that these spaces facilitate not tolerance, but the development of culturally hybrid practices and identities (Bhaba, 1998) that push us to animate our language repertoires in creative and novel ways. Shifting to an asset-based paradigm like translanguaging upends, and arts-based processes can power these shifts in dynamic and unexpected ways.

As the world shrinks and linguistic inequality becomes increasingly complex, collaborative arts-based approaches can play an essential role in centering emotion-oriented ways of knowing as powerful ways to access and develop the autonomous self as a social, relational, affective being.

Notes on the Contributors

Yimeng Jin is a PhD candidate at Kyushu University in cognitive sciences. Her research spans linguistic/educational psychology and behavioral economics. Fluent in Mandarin, English, and Japanese, she is also passionate about translanguaging spaces and exploring how language influences thought and behavior across different contexts.

Yaya Yao (she/they) is a doctoral researcher at Kyushu University’s Faculty of Design and an adjunct lecturer at Kyushu Sangyo University. She is the author of a collection of poetry on language and lineage, Flesh, Tongue, and the lead writer of a handbook on equity, diversity, and inclusion for teachers, the Educators’ Equity Companion Guide. Yaya lives in Fukuoka, Japan with her family.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the self-access center’s staff and to Lasni Buddhibhashika Jayasooriya, Risa Ikeda, and Kathleen Brown for providing feedback on an earlier version of this article.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyushu University’s Graduate School of Design. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

Yimeng Jin and Yaya Yao contributed equally to the study, from the design and conduct of the workshop to data analysis and manuscript writing. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) SPRING Grant Number JPMJSP2136, as well as by a grant from the Office for the Promotion of Gender Equality at Kyushu University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Bhaba, H. K. (1998). The location of culture. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203820551

Blackman, L. (2021). The body (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Bovill, C. (2020). Co-creation in learning and teaching: the case for a whole-class approach in higher education. Higher Education, 79, 1023–1037. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00453-w

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Busch, B. (2012). The linguistic repertoire revisited. Applied Linguistics, 33(5), 503–523. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ams056

Chan, W. M., & Chi, S. W. (2011). Popular media as a motivational factor for foreign language learning: The example of the Korean Wave. In W. M. Chan, K. N. Chin, M. Nagami, & T. Suthiwan (Eds.), Media in foreign language teaching and learning (pp. 151–188). Mouton de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781614510208.151

Coffey, S. (2015). Reframing teachers’ language knowledge through metaphor analysis of language portraits. The Modern Language Journal, 99(3), 500–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12235

Cook-Sather, A. (2018). Listening to equity-seeking perspectives: how students’ experiences of pedagogical partnership can inform wider discussions of student success. Higher Education Research and Development, 37(5), 923–936. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1457629

Domínguez-Gaona, M., López-Bonilla, G., & Englander, K. (2012). Self-access materials: Their features and their selection in students’ literacy practices. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(4), 465–481. https://doi.org/10.37237/030410

Eguchi, S. (2014). Ongoing cross-national identity transformation: Living on the queer Japan-US transnational borderland. Sexuality & Culture, 18(4), 977–993.

Eschenauer, S. (2018). Translanguaging and empathy: Effects of performative approach to language learning. In M. Fleiner & O. Mentz (Eds.), The arts in language teaching. International perspectives: Performative – aesthetic – transversal (Vol. 8, pp. 231–260). LIT Verlag. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01942544

García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Wiley-Blackwell.

Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Newbury House.

Gastaldo, D., Magalhães, L., Carrasco, C., & Davy, C. (2012). Body-Map storytelling as research: Methodological considerations for telling the stories of undocumented workers through body mapping. http://www. migrationhealth.ca/undocumented-workers-ontario/body-mapping

Gastaldo, D., Rivas-Quarneti, N., & Magalhaes, L. (2018). Body-map storytelling as a health research methodology: Blurred lines creating clear pictures. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.2.2858

Hamman, L. (2018). Translanguaging and positioning in two-way dual language classrooms: A case for criticality. Language and Education, 32(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2017.1384006

Holliday, A. (2006). Native-speakerism. ELT Journal, 60(4), 385–387. https://doi.org/10.1093

Hooper, D. (2023). Exploring and supporting self-access language learning communities of practice: Developmental spaces in the liminal [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Nagoya University of Foreign Studies]. https://nufs-nuas.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/1814/files/(O7)Hooper_%E5%8D%9A%E5%A3%AB%E8%AB%96%E6%96%87%E5%85%A8%E6%96%87.pdf

Kaminskiene, L., & Khetsuriani, N. (2019). Co-creation of Learning as an Engaging Practice. SOCIETY. INTEGRATION. EDUCATION. Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference, 2, 191–199. https://doi.org/10.17770/sie2019vol2.3708

Kato, S., & Yamashita, H. (2012). The wheel of language learning: A tool to facilitate learner awareness, reflection, and action. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 164-169). Pearson Education. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833040

Kimura, H. (2014). Establishing group autonomy through self-access center learning experiences. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(2), 82–97. https://doi.org/10.37237/050202

Kriukova, O. (2022). Korean pop culture reshaping Korean teaching. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 173(2), 172–196. https://doi.org/10.1075/itl.21010.kri

Krumm, H.–J. (2011). Multilingualism and subjectivity: “Language portraits” by multilingual children. In G. Zarate, D. Lévy, & C. Kramsch (Eds.), Handbook of multilingualism and multiculturalism (pp. 103–106). Éditions des Archives.

Krumm, H.-J. (2007). Profiles instead of levels: The CEFR and its (ab)uses in the context of migration. The Modern Language Journal, 91(4), 667–669. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00627_6.x

Kusters, A., & Meulder, M. D. (2019). Language portraits: investigating embodied multilingual and multimodal repertoires. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.3.3239

Li Wei (2011). Moment analysis and translanguaging space. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(5), 1222–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035

Mercer-Mapstone, L., Dvorakova, S. L., Matthews, K. E., Abbot, S., Cheng, B., Felten, P., Knorr, C., Marquis, E., Shammas, R., & Swaim, K. (2017). A systematic literature review of students as partners in higher education. International Journal for Students as Partners, 1(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v1i1.3119

Mohamed, N. (2021). Representations of power and prestige in children’s multimodal narratives of linguistic identities. In Poteau, C. E., & Carter, A. W. (Eds.), Advocacy for social and linguistic justice in TESOL (pp. 55–73). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003202356-5

Moore, A. R. (2023). Linguistic dissociation: A general theory to explain the phenomenon of linguistic distancing behaviours. Applied Linguistics, 44(6), 1152–1171. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amad004

Moriya, R. (2019). Longitudinal trajectories of emotions in four dimensions through language advisory sessions. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 10(1), 79–110. https://doi.org/10.37237/100106

Mynard, J., & Shelton-Strong, S. (2022). Self-determination theory: A proposed framework for self-access language learning. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning, 4(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.52598/jpll/4/1/5

Parker, P. S., Holland, D. C., Dennison, J., Smith, S. H., & Jackson, M. (2017). Decolonizing the academy: lessons from the graduate certificate in participatory research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Qualitative Inquiry, 24(7), 464–477. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800417729

Rampton, M. B. H. (1990). Displacing the ‘native speaker’: Expertise, affiliation, and inheritance. ELT Journal, 44(2), 97–101. https://doi.org/10.1093/eltj/44.2.97

Rosa, J., & Flores N. (2017). Unsettling race and language: Toward a raciolinguistic perspective. Language in Society, 46(5), 621–647. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404517000562

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Saville-Troike, M. (2006). Introducing second language acquisition. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316569832.002

Schmied, A., Ntonia, I., Ng, M. K. J., Zhu, Y., Gibbs, F., & Zou, H. G. (2024). Co-creating with students to promote science of learning in higher education: An international pioneer collaborative effort for asynchronous teaching. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 35, 100229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tine.2024.100229

Schutz, P. A., Hong, J. Y., Cross, D. I., & Osbon, J. N. (2006). Reflections on investigating emotion in educational activity settings. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 343–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9030-3

Shelton-Strong, S. J., & Mynard, J. (2018). Affective factors in self-access learning. Relay Journal, 1(2), 275-292. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010204

Shintaku, K. (2022). Self-directed learning with anime: A case of Japanese language and culture. Foreign Language Annals, 55, 283–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12598

Solomon, J. (2007). “Living with X”: A body mapping journey in time of HIV and AIDS. Facilitator’s guide. REPSSI. https://apssi.org/product/living-with-x/

Swain, M. (2013). The inseparability of cognition and emotion in second language learning. Language Teaching, 46(2), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000486

Tassinari, M. G. (2016). Emotions and feelings in language advising discourse. In C. Gkonou, D. Tatzl, & S. Mercer (Eds.), New directions in language learning psychology. second language learning and teaching. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-23491-5_6

Tassinari, M. G., & Ciekanski, M. (2013). Accessing the self in self-access learning: Emotions and feelings in language advising. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(4), 262–280. https://doi.org/10.37237/040404

Thomas, E. E., & Stornaiuolo, A. (2016). Restorying the self: Bending toward textual justice. Harvard Educational Review, 86(3), 313–338. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-86.3.313

Tomlinson, B. (2010). Principles and procedures for self-access materials. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(2), 72–86. https://doi.org/10.37237/010202

Tomlinson, B. (2013). Introduction. In B. Tomlinson (Ed.), Developing materials for language teaching (2nd ed., pp. 1–12). Bloomsbury Publishing.

Tumanyan, M. & Huuki, T. (2020). Arts in working with youth on sensitive topics: A qualitative systematic review. International Journal of Education Through Art, 16(3), 381–397.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

White, C. J. (2016). Agency and emotion in narrative accounts of emergent conflict in an L2 classroom. Applied Linguistics, amw026. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amw026

Yamashita, H. (2015). Affect and the development of learner autonomy through advising. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 62–85. https://doi.org/10.37237/060105

Yao, Y. (2024). Translanguaging performance poetry for learner development. Learner Development Journal 8.

Appendix – Please see PDF version