Jon Rowberry, Sojo University, Kumamoto, Japan. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5349-5196

Erhan Aslan, University of Reading, UK. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4174-5493

Rowberry, J., & Aslan, E. (2024). “It’s difficult not to intervene sometimes”: Language teacher cognition, emotion, and agency in a self-directed learning unit. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(3), 507–528. https://doi.org/10.37237/202401

(First published online, February 14, 2024.)

Abstract

Despite the increasing recognition of language learning beyond traditional classrooms, little is known about how language teachers support and guide students in self-directed learning environments. Drawing on qualitative data from a team of experienced English as a Foreign Language teachers, this article reports on the intersections between teachers’ cognition, emotions, and agency in a self-directed language learning unit (SDLU) at a university in Japan. Thematic analysis of the data illuminated dialectal relationships between teachers’ feelings, beliefs, and agency during the implementation of the SDLU. Although teachers were supportive of SDLU’s goals and the overall approach it promoted, they were cautious of intervening in their students’ self-directed learning due to concerns about protecting the learner autonomy that SDLU was designed to foster. As well as confusion over how best to meet the needs of their learners in this novel context, they experienced vulnerability in relation to their professional identities and there was considerable variation in ways teachers enacted agency and managed the new learning environment. The findings suggest teachers may need guidance and support to help them recalibrate existing competencies and develop strategies for nurturing their students’ self-directed learning in novel classroom contexts.

Keywords: language teacher agency; teacher cognition; teacher emotions; teacher roles; self-directed learning; language learning advising

The emergence of communicative language teaching in the latter half of the 20th century afforded opportunities for decentralized control with authority more evenly distributed between teachers and learners (Nunan, 1988) in the English language classroom. This implies a shift in the role of classroom teachers away from “teaching” and towards facilitating learner-centered collaborative activities, as well as supporting learners to create individualized learning pathways (Healey, 2016). This repositioning has been associated with terminology, such as “facilitator”, “mentor”, “counsellor”, “adviser”, “helper”, and “consultant” (Mozzan-McPherson, 2001), while interactions between instructors and learners may be referred to as “learning conversation” (Kelly, 1996), “counselling” (Gardner & Miller, 1999), or “reflective dialogue” (Kato & Mynard, 2016). It has also been accompanied by the emergence of a new field, language learning advising, which is generally associated with language learning beyond the classroom (LLBC), particularly in the context of self-access centers. However, transitioning to advisory roles can have implications for what teachers feel and believe, as well as for their agency in re-envisioning pedagogical practices.

In fact, while learners remain largely subservient to teachers and educational institutions (Betancor-Falcon, 2022), increasing learner agency and autonomy is viewed as a desirable goal of language teaching. However, there is surprisingly little evidence of teacher behavior that actively supports or promotes it (Reinders, 2021). As a result, little is known about how teachers encourage, support, and guide students for LLBC (Reinders & Benson, 2017); how LLBC practices are influenced by teachers’ beliefs; and how emergent and innovative learning environments challenge teachers’ beliefs and practices (Graves, 2008).

This case study explores the intersections between language teacher cognition, emotions, and agency relating to shifting classroom roles following the introduction of a self-directed learning unit (SDLU) at a university in Japan. SDLU was devised as a bridge between classroom-based language instruction and LLBC, and it aims to promote and nurture learner agency to sustain students’ language learning after they have completed their required English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classes. Since there is little whole class teaching in SDLU, teachers may find it difficult to utilize their previously learned teaching techniques and management strategies. Voller (1997), argues that in such contexts the teacher needs to perform three distinct roles, those of facilitator, counsellor, and resource. This suggests that teachers’ management of learning in SDLU is likely to be complex and demanding. However, they may not be appropriately trained to draw on the skills and strategies needed to nurture self-directed learning in this novel teaching context.

Although similar units have been described in other language learning sites, including Japanese universities (Carson, 2012; Ohashi, 2018), research on how teachers adapt to such environments is scarce. In the Japanese context, research investigating teachers’ experiences of managing self-directed learning has tended to focus on self-access centers (SACs) (Benson, 2001; Gardner & Miller, 1999; Morrison, 2008) and the role of language learning advisors (LLAs). For example, Beeching (1996) reported that teachers not only lacked the training and experience required for advisory roles, but that they were suspicious and resentful of being asked to perform them. Meanwhile, research by Morrison and Navarro (2012) showed that novice advisors had trouble striking a balance between guiding and prescribing, and they felt dissatisfied with their questioning techniques because they tended to jump in too quickly without giving learners sufficient time to pause and reflect. Similarly, van Rossum (2001) noted that advisory roles required a different kind of dialogue than the initiation-response-feedback interactions that typify traditional teaching, and teachers attempting to bridge these two roles found the experience challenging and uncomfortable. Meanwhile other studies have focused on how teachers manage the transition from in-person to virtual classrooms (see, for example, Naylor & Nyanjom, 2021).

The current study aims to build on this extant research by exploring the dialectal relationships between cognition, emotions, and agency (Golombek & Doran, 2014) when teachers transition from directive to supportive roles as they implement SDLU, a context in which they remain situated in the physical classroom and therefore retain their established teacher identity. The research question that guided the study was:

- How does a shift in the learning environment affect teachers’ cognition, emotions, and agency with respect to their roles?

In what follows, we discuss the intersections among teacher cognition, emotions, and agency. Following this empirical, conceptual, and contextual background, we present the methodology and findings of the study.

Teacher Cognition, Emotions, and Agency

Borg (2011) defines teacher cognition as “what teachers think, know, and believe, and how these relate to what teachers do”(p. 218). Extant research on teacher cognition provides insights into the unobservable mental lives of teachers and the complex ways their thoughts, knowledge, and beliefs impact their classroom practices. For example, teachers use techniques that they believe are most effective (Breen,1991), and they teach grammar explicitly if they believe in explicit grammar instruction (Burgess & Etherington, 2002). Li (2017) highlights the multi-layered nature of teacher cognition that encompasses thinking, knowing, understanding, conceptualizing, and stance-taking in social interactions in micro-contexts. Teachers who are ostensibly committed to learner-centered approaches may still experience challenges in transitioning into alternative classroom roles in unfamiliar language learning and teaching settings.

Because teaching is not only a mental activity but also a social one (Richards, 2022), teacher cognition is closely associated with emotions. Classroom interactions Language teacher emotions are connected to emotion labor defined by Benesch (2017) as the ways in which “humans actively negotiate the relationship between how they feel in particular work situations and how they are supposed to feel, according to social expectations” (pp. 37–38). Positive and negative emotions can result from teachers’ everyday interactions and experiences within their teaching context, and such emotions may pertain to their own teaching, their colleagues or students, teaching materials and resources, and their overall satisfaction in the profession. In fact, research on novice language teachers has identified several constructs related to emotions such as “contradictions” (Vygotsky, 1978), “tension” (Golombek, 1998; Johnson, 1996), and more recently “emotional dissonance” (Childs, 2011; Golombek & Johnson, 2004).

Rooted in the concept of teaching-as-caring, Miller and Gkonou (2018) found that emotions affect teachers’ agentic choices and actions including managing emotionally challenging situations, developing good relationships with students, and avoiding emotional entanglement. Emotion labor pertaining to contextual conditions and policies conflicting with teachers’ professional expertise can be a driving force for teachers to exercise agency to challenge existing practices (Benesch, 2018). The ways in which teachers customize their classroom practices, modify their interactions with students and colleagues, and reconfigure their professional identities, has been described by as job crafting, and this contributes to their psychological well-being (Falout & Murphy, 2018, p. 213). Teacher cognition, emotions, and agency are in constant interaction, affecting the ways teachers plan, enact, and reflect on their teaching at both conscious and unconscious levels (Golombek & Doran, 2014). While such dialectal relationships are generally investigated in novice teachers’ professional development (Galman, 2009; Golombek & Doran, 2014, Johnson, 1994), they bear particular importance in teaching contexts where experienced teachers face new demands or adapt to new pedagogies and ways of teaching and interacting with students.

By exploring teachers’ cognition and emotion labor amid changing classroom practices in the context of SDLU, we aimed to uncover how teacher agency may be affected in particular contexts. In addition, we hoped the study would provide opportunities for participants to reflect on and discuss their own teaching experiences as a form of reflective practice (Farrell, 2015), and that the findings would inform the ongoing development of SDLU procedures and resources, ultimately leading to improvements in learning outcomes.

The Study

The study was conducted at a regional university in Japan, offering degree programs in science and engineering disciplines. Several years prior to the introduction of SDLU, the university had established a dedicated facility containing networked teaching rooms and a large SAC to enhance the English abilities of its students and employees. SDLU was conducted in this facility and the first author, as well as all participant teachers, was employed there.

The Self-Directed Learning Unit

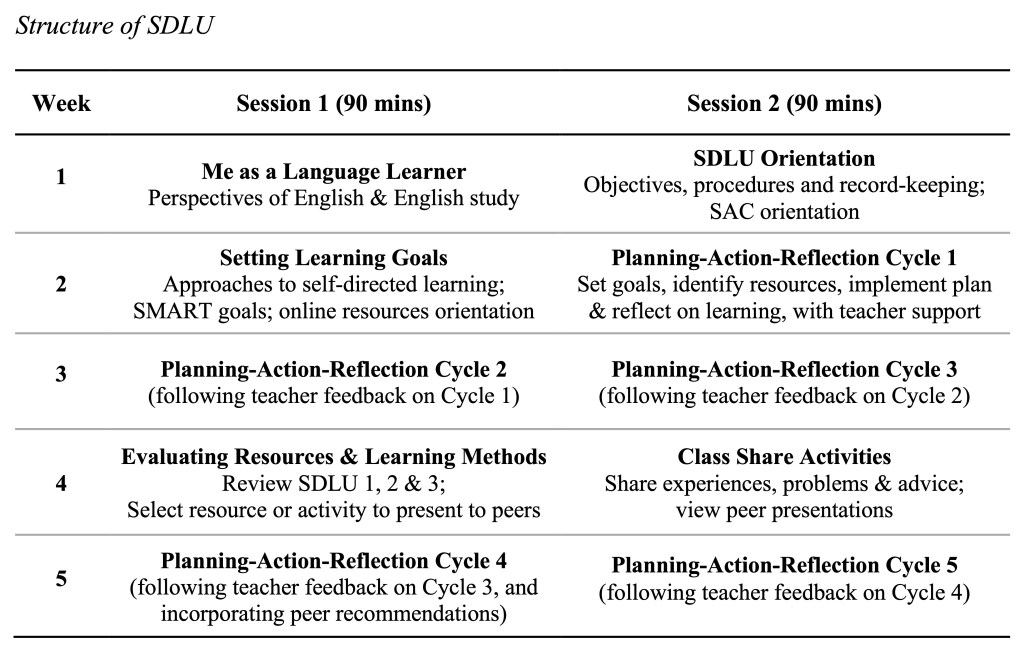

Students encounter SDLU during their second year of undergraduate study as a subcomponent of a compulsory EFL program. In SDLU students are encouraged to interact with English agentively through the guided exploration of a learning environment containing a wide variety of potential resources for learning, with help and advice from teachers and peers. The unit comprises ten 90-minute sessions, conducted in established classes of 25 to 30 students under the supervision of the students’ regular teacher. During SDLU sessions, students formulate personal goals for language learning, identify appropriate resources, draw up and implement study plans, self-evaluate their performance, and critically reflect on the learning process. The overall structure of the unit is shown in Table 1. At the heart of SDLU are five planning-action-reflection cycles, a term taken from Ohashi (2018), who describes a similar self-directed learning program at another Japanese university. Learners spend 15 to 20 minutes setting goals, planning what to study, and searching for suitable materials, 60 minutes implementing their plan, and finally, around 15 minutes evaluating the resources used, and writing a learning reflection focusing on the effectiveness of their activities in meeting their learning goals. Everything is recorded in a self-directed learning portfolio, typically written in their L1, Japanese.

Table 1

Once oriented to procedures and parameters, learners are free to choose what to study, what resources to use and how to use them, as well as whether to work in the classroom or the SAC, and alone or with peers. Unless a problem arises, teachers try to avoid directing the learning; instead, they are primarily engaged in supporting students by answering questions, suggesting resources, providing feedback, or participating in learning tasks, as well as monitoring what students do since participation in SDLU contributes to course grades. Prior to SDLU, a teacher orientation session was held in which the rationale for the unit, as well as recommended procedures and resources, were explained and teachers had an opportunity to ask questions, raise concerns, and make suggestions. However, they received no formal training to prepare them for the shift in their role implied by the implementation of SDLU.

Data Collection

The perspectives of SDLU teachers were investigated via a survey and semi-structured interviews. Ethical approval was obtained from the research site and participants provided written consent for their data to be used. The survey data was collected from all 10 teachers responsible for implementing the unit. Teachers were asked to provide written responses to a series of question prompts, which targeted their perspectives regarding student engagement with SDLU, its effectiveness in addressing program goals, and how its implementation had impacted their own teaching practices (see Appendix 1). To elicit emotions, teachers were specifically asked what roles they had performed while delivering the unit and how they felt about performing them.

Following the subsequent iteration of SDLU the following year, the first author conducted semi-structured interviews of between 30 and 60 minutes in duration with six colleagues. The interview was based around seven topics designed to elicit insights into participants’ classroom practices and emotional responses to the novel teaching context (see Appendix 2 for interview protocol). Participant anonymity has been preserved using pseudonyms. It was not possible to interview all 10 SDLU teachers because of time constraints, but the six teachers selected were broadly representative of the wider population in terms of age, gender, cultural background, and teaching experience, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Research Participants

Data Analysis

Interview recordings were transcribed by the first author, then both authors read through the transcripts and survey responses independently making provisional memos. As an outsider with limited familiarity with the research site, the second author brought an etic perspective to the data analysis process to complement the emic positionality of the first author, a member of the SDLU teaching team. While the positionality of the first author was vital in gaining access to the site and the participants, as well as in-depth knowledge of the SDLU context, the etic perspective of the second author served to minimize the risk of bias when analysing data and interpreting findings due to the close working relationship between the first author and the participant teachers.

Data referencing teachers’ practices, feelings, and beliefs in relation to SDLU were identified and coded in the qualitative data analysis software MaxQDA. Inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; 2012) was employed in an iterative process of categorizing the data into codes, identifying emergent themes from the codes, developing interpretations of the themes, and returning to the data to reassess and refine the interpretations. During and following discussions between the two authors, identified themes were further scrutinized and linked to specific interview extracts.

Subsequently, initial findings from the study were presented at an informal professional development workshop at the research site. This took place during the academic year after interviews had been conducted, and shortly before the next iteration of SDLU. This session provided an opportunity for participant validation by allowing members of the SDLU teaching team to discuss and endorse, or question, our interpretations of the data. As Duff (2008) notes, member checking of this nature not only serves as an additional form of triangulation but also foregrounds issues of representation and collaboration between those conducting investigations and those being investigated.

Findings

In response to the research question as to how the shift from a traditional classroom environment to SDLU affected teachers’ cognition, emotions, and agency, the analysis of the interviews revealed two major themes: re-envisioning teacher roles and management of learning in SDLU. In what follows, we describe each theme with relevant excerpts from the interview data.

Re-Envisioning Teacher Roles in SDLU

While participant teachers had a favourable impression of SDLU, and reported high levels of engagement among their students during SDLU sessions, many of them expressed discomfort about their classroom role. That is, they appeared to experience a disconnect between their beliefs about SDLU, which were positive, and their feelings as the unit was enacted in the classroom, which were more ambivalent.

Teachers reported that they monitored students during self-directed learning sessions but tried not to intervene unless learners requested advice or needed some practical help, such as locating a resource. Teachers sometimes asked students to explain what they were working on, and several teachers said that they set up more formal consultations with individual students to discuss their progress. However, when not directly occupied with students, teachers reported that they spent time chatting with colleagues or self-access center staff, or sitting at their desks checking student portfolios. Although such classroom behaviors were entirely legitimate in the context of SDLU, one of the survey respondents said they felt like “a spare part” (Respondent 7, survey) at such times, while Finley said he felt like “a bit of a fraud” (Finley, interview). One participant teacher jokingly asked, “what actually is my job?” (Carey, interview), while a survey respondent stated, “I often felt I should be doing something to justify my role in the classroom, though I don’t think the students really noticed or cared” (Respondent 3, survey).

Teachers’ comments about being superfluous to the learning were typically offered rather jokingly in a tone of self-deprecation. However, they highlight teachers’ emotions regarding their role in SDLU and reveal legitimate concerns about teacher identity. Finley, for example, said, “having seen what happens with SDLU, it really just makes me wonder how necessary I am.” This experience led Finley to question not only his own individual approach to teaching but the broader sociohistorical approach to language education as a whole:

I probably shouldn’t be saying this, but being up in front of a class, the traditional classroom teacher type role, I’m wondering…if there are enough people who are researching things like this, it might start to prove that we’ve been doing education wrong for hundreds of years. (Finley, interview)

The non-traditional learning environment of SDLU forces him to revisit his beliefs about teaching, teacher roles, and teacher identity, and it is interesting that he prefaces his comments with the rather conspiratorial “I probably shouldn’t be saying this,” as if he is conscious of undermining his own professional raison d’être. We see here the interplay between Finley’s beliefs about teaching (as shaped by his teacher cognition), how he associates these beliefs with actual teaching behavior (his own teacher agency), and how this process of questioning makes him feel – like a fraud or somewhat redundant.

It is worth noting that teachers’ uncertainty about their role was often driven by a concern about how their classroom behavior may be perceived by outsiders. For the teachers themselves, their non-directive role was a conscious and reasoned decision, consistent with the goals of SDLU and established classroom procedures. However, they speculated that those not privy to this rationale may assume they were simply lazy or uncaring, or, as Yuki put it, “not really working” (Yuki, interview). One of the survey respondents explained:

I was self-conscious about the fact that the students themselves, as well as colleagues and visitors passing by the glass-walled classroom, might wonder what I was (or wasn’t doing) and question my commitment to my professional responsibilities. (Respondent 7, survey)

Such comments appear closely related to what Kelchtermans (2005) refers to as vulnerability, a dimension of teachers’ experience associated with the “feeling that one’s professional identity and moral integrity, as part of being ‘a proper teacher’ are questioned” (p. 997). These concerns about what others might think may have amplified teachers’ own doubts and uncertainties. As Finley put it, “most of us probably have preconceived notions of what it means to be a teacher,” (Finley, survey) and, consciously or otherwise, teachers may themselves view supportive classroom roles as carrying less status than directive roles. Such views sometimes co-occurred with the contradictory belief that learner-centered classrooms provide the optimal conditions for learning. Respondent 7 seemed quite conscious of this irony, reporting that their “feeling of embarrassment” and “sense of inadequacy” regarding their role in SDLU persisted despite them being “deeply committed to an active learning approach” and their belief that “it should be the students doing the hard work during English class rather than the teacher, whose energies should be setting up and facilitating the learning”(Respondent 7, survey).

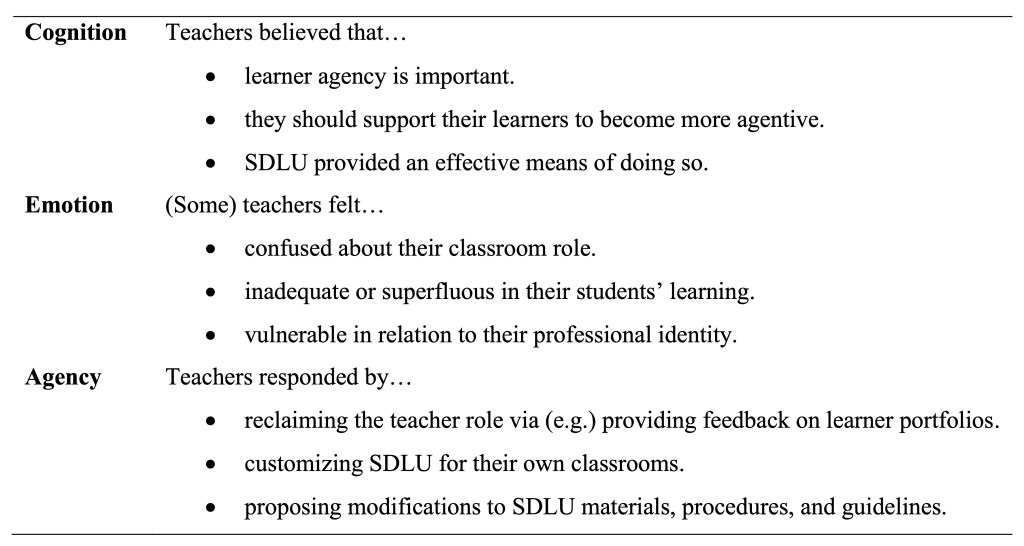

Figure 1

Dialectal Relationship Between Teacher Cognition, Emotion, and Agency

Note: Adapted from Golombek & Doran, 2014, p. 107

Several teachers appeared to compensate for their less prominent roles inside the classroom by focusing more on their roles outside class, including instructional design. For example, Sam developed and shared a comprehensive and elaborate set of alternative procedures for orienting students to the SDLU (Sam, interview). Teachers also expended considerable time and effort providing feedback on students’ self-directed learning portfolios. As Finley put it, “I feel like I’m allowed to be a teacher, so to speak, when I’m checking the portfolios…I feel like I’m playing my teacher role there more” (Finley, interview). Such efforts may be interpreted not only as serving a practical purpose in meeting students’ needs but also as performing a psychological function in enacting agency to reclaim the teacher’s role, as shown in Figure 1 (adapted from Golombek & Doran, 2014). In other words, teachers were trying to be who they think they should be by enacting their teacher agency to alleviate their feelings of uselessness or inferiority.

Management of Learning in SDLU

Teachers reported implementing SDLU in individual ways in their own classrooms. Regarding procedures for orienting students to SDLU, Emerson remarked, “there are things students need to know but how you get that through to them, that’s your job as a teacher” (Emerson, interview). Teachers also developed their own systems for providing feedback. While Emerson adopted a points-based system to help students understand how they were being assessed, Finley focused more on feedback comments to nurture reflective dialogue with his students. Such examples demonstrate the varying manifestations of teacher agency in adapting to a new educational setting.

Uncertainty over whether, when, or how to intervene in the learning process was expressed by multiple participants. Two of the interviewed teachers adopted a laissez-faire approach to classroom intervention arguing that students should follow their own course to learn from their mistakes. While acknowledging that “it’s really difficult not to intervene sometimes,” Carey suggested that the best form of intervention is not in the moment, but outside of class in responding to students’ written reflections (Carey, interview). Emerson also preferred to be “hands off” and to “pretty much let people go,” even despite having reservations about activities students were doing:

If they’re doing something that I don’t think is particularly efficient or useful, then maybe they can reflect on it. I’m not sure it’s my place to jump in. Maybe just sit back and shut up for a few lessons. I’d prefer to do that than ‘why don’t you try what I think is good for you.’ (Emerson, interview)

Other teachers, however, felt that it was important to intervene more proactively during class sessions, for example, to provide advice on record-keeping, to suggest resources or supplementary tasks, or even to manage behavior. However, teachers were wary of interrupting the flow of students’ self-directed learning and were conscious that intervention risked re-appropriating from their learners the control over learning decisions that they were attempting to cede. Remy described a situation in which one of the students in her class, who was reading a text that seemed well beyond their level, resisted her attempted intervention:

I said to him ‘you may want to skip this and go to a different section’ and he was like ‘not doing it’ and I was like ‘alright (laughing), go ahead, do what you’ve got to do.’ (Remy, interview)

Nevertheless, many teachers remained concerned that they were not intervening sufficiently or appropriately in their students’ in-class learning. Sam noted a tendency for himself and other colleagues to retreat behind the teacher’s desk during SDLU. He argued that teachers should resist this temptation since it is important for them to be “out there…visible” to the learners, even if not always needed (Sam, interview). However, given that learners were free to work wherever they chose in the building, this was not always straightforward.

Discussion

The findings of this study, as summarized in Table 3, indicate intricate relationships between teachers’ beliefs and practices, as well as diverse emotions evoked in the process of the SDLU implementation. Navigating around their emotions, cognition, and agency, the teachers were able to support their students’ learning fulfilling the role of “bridging figure” (Mozzon-McPherson, 2001) between the institutionalized classroom-based learning and LLBC. Although they experienced emotional dissonance regarding their classroom role and vulnerability in relation to their professional identity, there was certainly no sign of the suspicion, skepticism, resentment, or resistance expressed by teachers towards the role of facilitator, highlighted by Beeching (1996).

Table 3

Key Findings

Despite evidence of both individual and collective agency as teachers implemented SDLU, and the high level of student engagement they reported, teachers expressed negative emotions such as uncertainty and confusion over how best to meet the needs of their learners in this novel context. This was despite there being no indication from the data that the students themselves resisted or even noticed their teachers’ repositioning. This resonates with van Rossum’s (2001) report of classroom teachers performing counselling roles in which it was observed that the “dual role of the teacher is slightly uneasy, but probably more for the teacher than the students” (p. 228). As Morrison and Navarro (2012) point out, the shift from teaching to advising requires a reorientation not only of professional practice but also of identity, so it is not surprising that participant teachers experienced vulnerability.

The data revealed a mismatch between SDLU teachers’ beliefs regarding the importance of ceding control to the learners and their feelings as this process unfurled. As Kelchtermans (2005) notes, “emotion and cognition, self and context, ethical judgement and purposeful action: they are all intertwined in the complex reality of teaching,” (p. 996) and in the sudden change of circumstances necessitated by the introduction of SDLU, these complexities can be thoroughly exposed. Use of terms such as “fraud” and their concerns about what others might think demonstrated teachers’ need to actively manage emotion labor to reconcile how they felt with how they believed they should feel (Benesch, 2017).

The findings suggest that teachers may need to develop a broader and contextualized understanding of their role in novel learning environments like SDLU. Although the study participants were experienced and highly qualified, and they were able to manage the SDLU learning environment successfully overall, there appeared to be a lack of systematicity in managing learning and uncertainty over how to interact with students. Given the complexities associated with this consultancy role documented in the literature (Mozzon-McPherson & Vismans, 2001), and their lack of explicit training, it is not surprising that SDLU teachers were unsure whether, when, and how to intervene in their students’ self-directed learning. This resonates with the frustrations reported by novice advisors in Morrison and Navarro’s (2012) study regarding the difficulty in finding an appropriate balance between guiding and prescribing. The SDLU teachers wanted to be (or felt they should be) present in the learning process but were wary of getting in the way or unwittingly undermining their learners’ autonomy. As Sheerin (1997) notes, learning may be limited, and autonomy jeopardized, if teachers are too dominant in the role of consultant. Considerable skill and sensitivity are needed to find the right balance, which will differ from learner to learner according to various contextual factors, including the learning environment, learners’ individual attributes and preferences, and instructors’ teaching styles. However, it is vital that teachers do not shy away from intervening since “underadvising learners…may cause them to feel frustrated, isolated, and discouraged” (Sheerin, 1997, p. 64). Although direct impacts of teacher interventions on learners’ linguistic proficiencies may be difficult to discern, teachers’ involvement serves other important purposes, such as establishing rapport or stimulating dialogue, which may, in turn, enhance learning motivation and sustainability.

Implications and Conclusions

One implication of the research findings is that teachers may need guidance in the role of learning consultant if they are to enact and enhance their agency in non-traditional classroom environments. In fact, in-service teachers will already have developed many of the requisite skills and sensitivities. For example, familiar dilemmas such as whether, when, or how to provide corrective feedback on students’ written or oral output closely mirror the concerns experienced by the participant teachers regarding intervention in SDLU. Appropriately targeted guidance would enable teachers to transfer and recalibrate these skills, as well as to develop additional strategies for supporting their students’ self-directed learning.

A potential source of such professional development is the established field of language learning advising. Given the one-to-one contact time and specific expertise that learning advising demands, it is not possible for classroom teaching simply to be reconceptualized as learning advising. However, teachers do not need to become LLAs to draw on the skills and competencies developed through learning advisor training. For example, Esen’s (2020) study with teacher-advisors at a university in Turkey found that participants had positive beliefs about the impacts of advising on their teaching practice and their professional development, associated particularly with a better understanding of students’ needs, enhanced empathy, and more effective support for learning strategies. Recent narrative reports by Brown (2021) and Raluy (2022) have also highlighted the challenges and benefits of language learning advising training for classroom teachers, while Sampson (2020) noted how advisor training afforded him a different perspective for understanding language learners, added to his identity as an educator, and stimulated him to incorporate activities into his classes to enhance learner autonomy.

Collaboration between teachers and advisors in contexts such as SDLU is also likely to be mutually beneficial. As Carson (2012) argues, there are inherent advantages to both traditional teaching and learning advising, and a combination of these elements may produce more optimal learning outcomes. An example of such a combination is provided by Horai and Wright (2016), who describe a project in which a classroom teacher and an LLA worked collaboratively to incorporate advising sessions into a communicative English class at a Japanese university. They noted that both the teacher and the LLA learned more about their students’ needs and interests and that they communicated regularly to share ideas about the class, “as well as building a relationship that led to further collaboration” (p. 205).

A second implication from the study is that teachers would benefit from opportunities to express and explore their own emotional responses to unfamiliar classroom dynamics. It is noteworthy that many of the teachers reported feeling uncomfortable adopting non-directive roles even when the exigencies of the teaching environment demanded them. However, rather than being detrimental to teachers’ well-being, emotion labor can be viewed as a tool with significant agentive potential for stimulating collaboration with students and colleagues, leading to positive change (Benesch, 2018). The occasions during SDLU in which teachers were able to chat with colleagues and self-access center staff might be viewed not merely as filling time but as important opportunities both to share practical suggestions for implementing SDLU and to discuss and reflect on classroom experiences, including their emotional responses.

Finally, it is vital that teachers are not expected to uncritically implement innovations and practices handed down from above but given agency to shape and inform professional practices. Enhanced agency is supportive of teachers’ emotional health and professional wellbeing (Miller & Gkonou, 2018), whereas impeded agency negatively impacts teacher identity construction (Karimpour et al., 2022) and has been associated with burnout and stress (De Costa et al., 2018). There is evidence from the data that a collaborative culture was present at the research site and that this was highly valued by the study participants. As “reflexive and reflective agents” teachers do not passively absorb change but adapt, enhance, and resist, thereby proactively shaping their emergent professional roles and identities (Gao, 2019, p. 164). Opportunities to conduct or participate in research, such as the current study, which promote reflection, elicit feedback, and stimulate discussion of individual and collective practices, may promote the emergence of transformative agency, through which teachers are empowered to take the initiative to transform the environment (Kramer, 2018).

As a small-scale, localized project, this study has several limitations. The positionality of the interviewer as a member of the teaching team responsible for implementing SDLU is likely to have constrained responses to a certain extent, although the anonymous teacher feedback survey data aligned closely with the interview data. Moreover, five of the six participant teachers were from Anglophone countries, and it is likely that local Japanese EFL teachers may have experienced the shift from directive to supportive classroom roles in the context of SDLU differently (Aoyama, 2021). Similarly, all six participants were mid-career teachers, and the perspectives of newly qualified teachers, or those in the later stages of their careers, may differ significantly. Closer case-driven investigations of a diversity of teachers focusing on their professional experiences and identities as they adapt to non-directive teaching practices would therefore be a fruitful avenue for further research.

Notes on the Contributors

Jon Rowberry has extensive experience teaching English and EFL at both secondary and tertiary levels, and is now director of the Sojo International Learning Center in Kumamoto, Japan. His interests include practitioner research and language learning beyond the classroom. He is currently conducting a longitudinal investigation of learner agency in the context of self-directed language learning for a PhD in Applied Linguistics.

Erhan Aslan is an Associate Professor of Applied Linguistics at the University of Reading with a PhD in Second Language Acquisition and Instructional Technology from the University of South Florida. His second language learning and teaching-related research appeared in journals such as TESOL Journal, International Journal of Multilingualism and Canadian Modern Language Review.

References

Aoyama, R. (2021). Language teacher identity and English education policy in Japan: Competing discourses surrounding ‘non-native’ English-speaking teachers. RELC Journal, 54(3), 788–803. https://doi.org/10.1177/00336882211032999

Beeching, K. (1996). Evaluating a self-study system. In E. Broady & M. Kenning (Eds.), Promoting learner autonomy in university language teaching (pp. 81–103). Association for French Language Studies and The Centre for Information on Language Teaching and Research.

Benesch, S. (2017). Emotions and English language teaching: Exploring teachers’ emotion labor. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315736181

Benesch, S. (2018). Emotions as agency: Feeling rules, emotion labor, and English language teachers’ decision-making. System, 79, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.03.015

Benson, P. (2001). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. Longman/Pearson Education Limited. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833767

Betancor-Falcon, S. (2022). A critical history of autonomous language learning: Exposing the institutional and structural resistance against methodological innovation in language education. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 13(3), 332–346. https://doi.org/10.37237/130303

Borg, S. (2011). Language teacher education. In J. Simpson (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of applied linguistics (pp. 215–228). Routledge.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association.

Breen, M. P. (1991). Understanding the language teacher. In R. Phillipson, E. Kellerman, L. Selinker, M. Sharwood Smith, & M. Swain (Eds.), Foreign/second language pedagogy research (pp. 213–233). Multilingual Matters.

Brown, T. (2021). Stressing out about being genuine: Reflections on a first advising session. Relay Journal, 4(2), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/040205

Burgess, J., & Etherington, S. (2002). Focus on grammatical form: Explicit or implicit? System, 30(4), 433–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(02)00048-9

Carson, L. (2012). Why classroom based advising? In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools, and context (pp. 247–262). Longman.

Childs, S. S. (2011). “Seeing” L2 teacher learning: the power of context on conceptualizing teaching. In K. E. Johnson & P. R. Golombek (Eds.), Research on second language teacher education: A sociocultural perspective on professional development (pp. 67–85). Routledge.

De Costa, P., Rawal, H., & Li, W. (2018). L2 teachers’ emotions: a sociopolitical and ideological perspective. In J. Martinez Agudo (Ed.), Emotions in second language teaching: Theory, research, and teacher education (pp. 91–106). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75438-3_6

Duff, P. (2008). Case study research in applied linguistics. Routledge.

Esen, M. (2020). A case study on the impacts of advising on EFL teacher development. English Language Teaching Educational Journal 3(2), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.12928/eltej.v3i2.2477

Falout, J., & Murphey, T. (2018). Teachers crafting job crafting. In S. Mercer, & A. Kostoulas (Eds.), Language teacher psychology (pp. 211–230). Multilingual Matters.

Farrell, T. S. C. (2015). Promoting teacher reflection in second language education: A framework for TESOL professionals. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315775401

Galman, S. (2009). Doth the lady protest too much? Pre-service teachers and the experience of dissonance as a catalyst for development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(3), 468–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.08.002

Gao, X. (2019). The Douglas Fir Group framework as a resource map for language teacher education. The Modern Language Journal, 103(Supplement 2019), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12526

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

Golombek, P. R. (1998). A case study of second language teachers’ personal practical knowledge. TESOL Quarterly, 32(3), 447–464. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588117

Golombek, P. R., & Johnson, K. E. (2004). Narrative inquiry as a mediational space: examining cognitive and emotional dissonance in second language teachers’ development. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 10(3), 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354060042000204388

Golombek, P., & Doran, M. (2014). Unifying cognition, emotion, and activity in language teacher professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 39, 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.01.002

Graves, K. (2008). The language curriculum: A social contextual perspective. Language Teaching, 41(2), 147–181. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444807004867

Healey, D. (2016). Language learning and technology: Past, present, and future. In F. Farr & L. Murray (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language learning and technology (pp. 9–23). Routledge.

Horai, K., & Wright, E. (2016). Raising awareness: Learning advising as an in-class activity. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(2), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.37237/070208

Johnson, K. E. (1994). The emerging beliefs and instructional practices of pre-service English as a second language teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 10, 439– 452. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(94)90024-8

Johnson, K. E. (1996). The vision versus the reality: The tensions of the TESOL practicum. In D. Freeman & J. C. Richards (Eds.), Teacher learning in language teaching (pp. 30–49). Cambridge University Press.

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

Karimpour, S., Moradi, F., & Nazari, M. (2022). Agency in conflict with contextual idiosyncrasies: Implications for second language teacher identity construction. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 17(3), 678–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2022.2112200

Kelchtermans, G. (2005). Teachers’ emotions in educational reforms: Self-understanding, vulnerable commitment and micropolitical literacy. Teaching and Teacher Education 21(8), 995–1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.009

Kelly, R. (1996). Language counselling for learner autonomy. In R. Pemberton, E. Li, W. Or, & H. Pierson (Eds.), Taking control: Autonomy in language learning (pp. 93-113). Hong Kong University Press.

Kramer, M. (2018). Promoting teachers’ agency: Reflective practice as transformative disposition. Reflective Practice, 19(2) 211-224. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2018.1437405

Li, L. (2017). Social interaction and teacher cognition. Edinburgh University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780748675760

Miller, E. R., & Gkonou, C. (2018). Language teacher agency, emotional labor and emotional rewards in tertiary-level English language programs. System, 79, 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.03.002

Morrison, B. (2008). The role of the self-access center in the tertiary language learning process. System, 36(2), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2007.10.004

Morrison, B. R., & Navarro, D. (2012). Shifting roles: From language teachers to learning advisors. System, 40(3), 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2012.07.004

Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2001). Language advising: Towards a new discursive world. In M. Mozzon-McPherson & R. Vismans (Eds.), Beyond language teaching towards language advising (pp. 7–22). CILT.

Mozzon-McPherson, M., & Vismans, R. (Eds.) (2001), Beyond language teaching towards language advising. CILT.

Naylor, D., & Nyanjom, J. (2021). Educators’ emotions involved in the transition to online teaching in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(6), 1236–1250. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1811645

Nunan, D. (1988). The learner-centred curriculum: A study in second language teaching. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524506

Ohashi, L. (2018). Self-directed learning and the teacher’s role: Insights from two different teaching contexts. In P. Taalas, J. Jalkanen, L. Bradley, & S. Thouësny (Eds.), Future-proof CALL: language learning as exploration and encounters – short papers from EUROCALL 2018 (pp. 236–242). Research-publishing.net. https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2018.26.843

Raluy, D. (2022). A first attempt at advising: Getting comfortable with unfamiliar advising strategies. Relay Journal, 5(2), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/050204

Reinders, H., & Benson, P. (2017). Research agenda: Language learning beyond the classroom. Language Teaching, 50(4), 561–578. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444817000192

Reinders, H. (2021). A framework for learning beyond the classroom. In M. Raya & F. Vieira (Eds.), Autonomy in language education: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 63–73). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429261336-6

Richards, J. C. (2022). Exploring emotions in language teaching. RELC Journal, 53(1), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220927531

Sampson, R. (2020). Trying on a new hat: From teacher to advisor. Relay Journal, 3(2), 250–256. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/030211

Sheerin, S. (1997). An exploration of the relationship between self-access and independent learning. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 54–65). Longman. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315842172-5

van Rossum, M. (2001). Integrating advising into teaching: Two case studies of learners of Dutch. In M. Mozzon-McPherson & R. Vismans (Eds.), Beyond language teaching towards language advising (pp. 222–231). CILT.

Voller, P. (1997). Does the teacher have a role in autonomous language learning? In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning. (pp. 98–113). Longman. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315842172

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Harvard University Press. https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674576292

Appendix A

Teacher Feedback Survey Prompts

- How well do you think SDLU meets the language learning needs of the students you teach?

- How well did the students you teach engage with SDLU? Was this in line with your expectations?

- What role(s) did you perform during the five self-directed learning sessions? How did you feel about your role(s)?

Appendix B

Semi-Structured Interview Protocol

- How well do you feel the students in your classes engaged with SDLU?

- How did you monitor what students did during SDLU sessions?

- What do you think is your role as a teacher in SDLU? How do you feel about performing that role?

- Did you feel you were adequately prepared to teach SDLU? What additional information, training, or advice might have been useful as preparation?

- How did you decide whether to intervene in students’ learning during SDLU sessions?

- When and how did you provide feedback? What kind of feedback did you provide?

- Are there any changes you would like to see implemented for future iterations of SDLU?