Emily Marzin, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2737-4945

Diane Raluy, Nihon University, Japan

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3214-9507

Marzin, E. & Raluy, D. (2024). Student-led language learning community: The journey of a leader. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(3), 462–489. https://doi.org/10.37237/150308

Abstract

This study examines the role of a leader in a French language learning community at a Japanese university’s self-access center. Based on a previous study that focused on exploring the impressions of the members of this student-led community (Marzin & Raluy, 2023), results indicated the core role of the leader in enhancing motivation, (intercultural) communication skills, and sense of belonging. The present narrative study documents the experiences and reflections of the community leader, utilizing a range of reflective tools. The findings suggest that the leader’s regular introspection enabled him to assess his feelings, evaluate his decisions based on the community’s needs, and provide guidance to other members, with a focus on exploring World French and francophone cultures.

Keywords: student-led language learning community, autonomy-supportive leadership development, reflective practice

Language learners’ environments consist of a variety of spaces and communities that provide different resources, services, and activities, as described in Lai (2015) and Reinders and Benson (2017), including the setting of this research, a Self-Access Center (SAC) where the French Communication Group (FCG), a student-led French learning community, meets weekly. The FCG is comprised of students and university staff or teachers alike who voluntarily meet to help each other learn and practice French and share their cultural knowledge of the francophone world. The leader is a university student whose role is passed on from one leader to the next as they graduate or go study abroad. Designed to promote language study and practice, SACs also aim to encourage the development of autonomous behaviors and decision-making throughout users’ self-directed language learning process (Gardner & Miller, 1999), with the help of materials and personalized support (Reinders & Cotterall, 2001). Furthermore, studies have reported that language learners’ autonomy, agency, and engagement are partly connected to prosocial and informal learning opportunities to learn from and with others (Murray, 2014; Mynard et al., 2020) accessible face-to-face or online, in or out of the classroom (Reinders & Benson, 2017; Vygotsky, 1987), which SACs usually offer. An illustration of those facilities’ purpose in creating and encouraging collaborative language learning is student-led learning communities (SLCs). These consist of educational cohorts that connect members through shared interests and interactive learning in or out of the classroom (Kanai & Imamura, 2019; Watkins, 2022).

Results gathered through three data collection instruments revealed several benefits of these weekly meetings. Firstly, they provided the primary opportunity for members to listen to and speak French, interact with like-minded learners, and gain firsthand insights into francophone cultures. Secondly, the community served as a social space for members to reflect on their language-learning journey. Thirdly, effective leadership, which involved understanding members’ communication skills and adapting community dynamics accordingly, was crucial. Lastly, participants highlighted two key factors contributing to the community’s effectiveness: its welcoming atmosphere, which eased newcomers’ nerves, and its diverse membership, fostering cross-linguistic connections among individuals from various backgrounds and language proficiencies.

Started in 2018, the FCG aims to provide a space outside the French language course’s framework to practice communication skills and connect with other French speakers. In April 2023, the leader of this community completed her university studies, and a member took over this leading position. The present research explores the experiences of this SLC’s new leader. In particular, it brings attention to regular self- and co-reflection in and on actions to further understand the leader’s decision-making process and guide him into embracing a leadership role and the skills entailed. With this aim, the paper initially reviews key theoretical concepts related to SLCs and autonomy-supportive leadership development. It then outlines the methodological framework and data analysis procedures. Subsequently, the findings are discussed, followed by a conclusion that addresses study limitations and explores implications for SLCs, emphasizing the importance of self-reflection and guidance for leaders.

Theoretical Framework

This section provides an overview of SLCs outside traditional classroom settings, especially in SACs, and their significance in language learning. It also delves into the concept of leadership within SLCs through the lens of an autonomy-supportive approach to developing student leaders.

Studies on Communities of Practice (CoP), including SLCs, highlight three fundamental principles: a shared commitment to a common purpose, collaborative learning, and the exchange of mutual knowledge on operational procedures (Wenger, 1998; Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015). In addition to those elements, according to research with members of CoP (notably Hooper, 2020), it has been observed that the structure and content of the community’s practice shape members’ sense of ownership over this autonomous and social learning space: “the way learners imagine a space, perceive it, define it and express their understanding transforms a space into a place, determines what they do there and influences their autonomy” (Murray et al., 2014, p. 81) and, in some cases, of their learning process (see Mercer, 2012). Among the benefits that these communities offer, studies indicate that members get the opportunity to explore their identities as social actors through interaction (Bandura, 2008; Gao, 2009; Wenger, 1998), enhance their communicative, linguistic, and social skills (Murray & Fujishima, 2016), and receive emotional and motivational support, fostering confidence (Bibby et al., 2016), from peers with shared interests (Hughes et al., 2012). Moreover, such spaces facilitate identity development, including the emergence of Near-Peer Role Models (NPRM, Murphey, 1998a; 1998b; 2005) and envisioning future selves (Lamb, 2011; Murray, 2017).

Although there is no one-size-fits-all approach to ensure all community members’ voices are heard and their well-being prioritized, several authors provide guidelines, including hands-on and reflection activities, for stakeholders to support and strengthen SLCs in different settings (Kimball & Ladd, 2004; Watkins & Hooper, 2023; Wenger et al., 2002; Wenger-Trayner et al., 2022). In their handbook, Watkins and Hooper (2023) suggest the core agent who empowers (student) leaders to make decisions to create inclusive and sustainable learning environments is the student facilitator. The scholars propose the Cycle of Autonomy-supportive Learning model for those facilitators to assist student leaders (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Cycle of Autonomy-supportive Learning (Watkins & Hooper, 2023, p. 4)

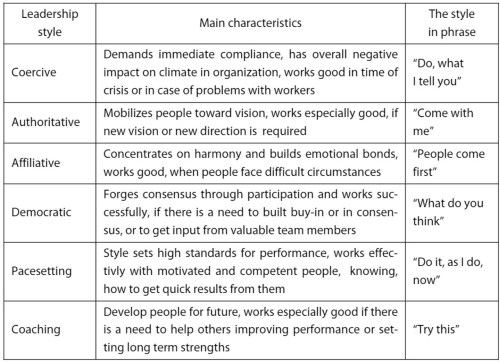

Based on theories related to student growth, empowerment, and well-being, the handbook activities and tools offer a structured approach for leaders to engage in meaningful reflection and enhance their leadership practice within the community. Aspects of this approach include reflecting on their identity (e.g., Atkinson, 1998), the community (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2022, among others), advising (e.g., Kato & Mynard, 2016), considering the basic psychological needs of the members, that consist of autonomy (the need to feel in control of one’s actions), competence (the need to feel effective and capable), and relatedness (the need to feel connected to others) (from Ryan & Deci, 2017, among others), adapting their leadership style (e.g., Goleman, 2000, see Table 1 below), and implementing iterative reflective learning cycles (e.g., Gibbs, 1988).

Table 1

Six Leadership Styles (Goleman, 2000, pp. 82-83)

As mentioned in the introduction, SACs aim to encourage students’ ownership of their language learning by providing resources and opportunities for interaction, including connecting with fellow learners. To this end, these facilities may support students participating and/or organizing events. Impacts on users involved in such activities have been described as increasing use of their target languages, peer support and motivation, and inspiration from NPRMs (see Yamashita, 2021, for experiences shared during the Japanese Association for Self-Access Learning student conferences).

While the present research focuses on the case of a French SLC in a Japanese SAC, other studies, including Castillo Zaragoza (2010) and Rubio (2014) in Mexico, have highlighted concerns about SACs focusing primarily on English practice at the expense of other Languages Other Than English (LOTE) spoken and studied. In particular, some recent Japanese research underscores the importance of providing resources and services catering to SAC users’ linguistic diversity (Marzin et al., 2023; Thornton, 2022). While scholars acknowledge the challenges SACs face in establishing or supporting SLCs (Fukuba, 2016; Hino, 2016), they also offer recommendations for creating multilingual environments and empowering students in their multilingual identities. These suggestions include:

- Incorporating the possibility of using multiple languages into the facility’s mission statement (Mynard et al., 2022).

- Employing student staff with expertise in LOTE (Pemberton et al., 2023).

- Organizing workshops or events such as international language festivals to promote linguistic diversity (Wongsarnpigoon & Watkins, 2022).

- Acquiring resources that support the practice of various languages (Thornton, 2022).

- Providing opportunities to interact with speakers of LOTE, such as through tandem learning programs (Marzin & Raluy, 2023) or SLCs (Hollinshead, 2022; Watkins, 2022), like the one examined in the present study.

The current study looks at the leader’s experience of a SLC student-led language group to understand what and how the decisions are made and what it reveals about his leadership style. By taking a narrative inquiry approach, this study seeks to answer the following research questions:

Research question 1: What is the student leader’s experience as an FCG member, co-leader, and leader?

Research question 2: To what extent does the leader’s oral reflection indicate an evolving autonomy-supportive leadership approach?

Narrative-oriented Approach

The narrative-oriented approach aims to explore and understand the stories individuals share (Miyahara, 2015). Narrative researchers seek to make sense of how participants redefine and reconstruct themselves on an individual and a social level through the discursive process. This study focuses on personal, social, institutional, linguistic, and cultural aspects of the FCG community leader’s journey as he co-leads, then at different stages of his leadership and, finally, when he passes on his responsibilities to the next leader. Analyzing the transition from one role to the next and the evolution of the leader’s perspective of what it means to be a leader will shed light on how he experienced this transition, his decisions, and his leadership style.

Context

This study was conducted at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS), a private, mid-sized Japanese university established in the 1980s. Specializing in global liberal arts, international relations, and languages, KUIS offers a wide range of language courses, including English, Indonesian, Thai, Korean, Chinese, Vietnamese, Spanish, and Portuguese. Additionally, certain language courses, such as French, are electives for first- and second-year students.

KUIS provides various language learning and practice facilities, including the Self-Access Learning Center (SALC). Established in 2001, this center’s mission is to encourage socialization in multiple languages and autonomous language learning in a multilingual and multicultural environment. It achieves this mission by offering resources, inclusive spaces, and services to empower students to take ownership of their learning process and enhance their confidence and proficiency in language study and use (Mynard et al., 2022).

To foster the learning and practice of languages offered at KUIS, the SALC facilitates community-based learning opportunities and provides a social learning space where students learn with and from each other by encouraging learners to participate in events (e.g., workshops, language festivals, stamps rallies) and supporting them to create and/or join SLCs. Since 2017, staff have provided logistical support to the community, including promoting them through events and poster displays onsite and on social media, organizing their weekly meetings, and providing reflection opportunities through a leadership course (Watkins, 2021).

Over the years, the FCG has had five student leaders who managed the community alone or in collaboration, among which one took the previously mentioned leadership course. Leaders were replaced due to study abroad stays or upon graduation. The FCG welcomes a wide range of members, including KUIS students, administrative staff, and teachers, totaling over 40 members. Attendance at community meetings varies from week to week, ranging from two to fifteen members, depending on availability, as participation is optional. Additionally, the group utilizes an instant communication application (Line) to discuss meeting topics and share general announcements.

Participant

Daisuke (pseudonym) joined the FCG in April 2022 as a member and assisted the then-leader between December 2022 and January 2023. He led the community from April to July 2023, in his third year at KUIS. Majoring in Portuguese, he can speak eight languages: Japanese (native language), Portuguese and English (formal learning), and Spanish, French, Russian, German, and Italian (self-taught).

At the time, Emily served as a coordinator for the learning communities, where she acted as a facilitator to help the leader reflect on his experiences during weekly one-on-one sessions (see next section). We are both native French speakers; we were FCG members and served as resources for the rest of the community. The leader assigned Diane to help beginners, while Emily was responsible for facilitating discussions for intermediate- and advanced-level members.

As researchers, KUIS staff, and members of the FCG community, we are aware that while our positions helped us to access the leader’s impressions easily and have preexisting knowledge of the study context, our experiences, responsibilities, and beliefs may shape the research process and outcomes, including our interpretation of the narrative collected. To mitigate possible drawbacks and enhance the trustworthiness of the research findings, we requested Daisuke and a third party to read our interpretation of the data.

Data Collection

This study explores Daisuke’s experience as the co-leader and leader of an SLC, the FCG, to understand what sense he made of his leadership experience and how he transitioned from a member and a co-leader to a leader position. Appendix A presents an overview of the data collection procedure, including the instruments and the dates when the experiences were collected.

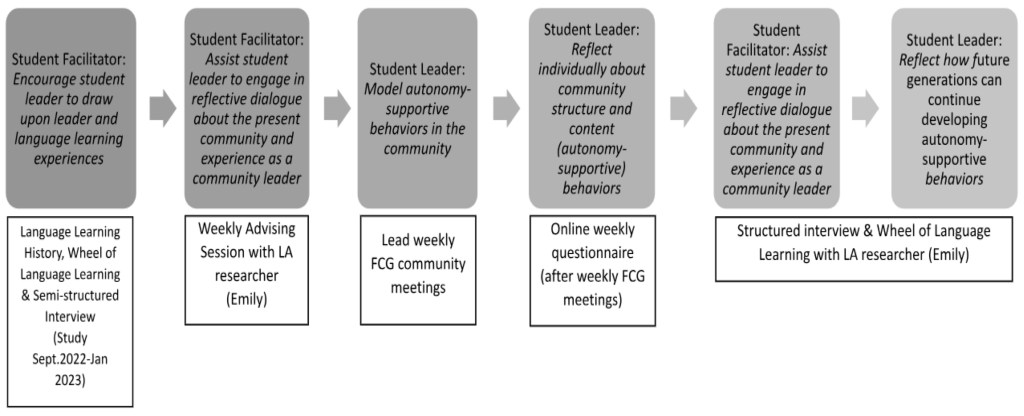

Since the Cycle of Autonomy-supportive Learning developed by Watkins and Hooper (2023) aligned with the objectives of the present research, it was decided to adapt this model and the data collection instruments used to its particular setting. Figure 2 outlines the steps taken to support Daisuke, including the instruments conducted to collect his leadership experience.

Figure 2

The Cycle of Autonomy-supportive Learning to Collect the Experience of the FCG Leader (adapted from Watkins & Hooper, 2023, p.4)

After project received approval from the university, and that the participant signed a consent form, at the beginning of the semester (September 2022), the first phase of the study, conducted as part of a previous investigation (see the introduction section for background), involved compiling members’ language learning experiences, including Daisuke’s. This was done using adapted versions of the Language Learning Histories from Murphey (1988a) and the Wheel of Language Learning (WLL) from Kato and Mynard (2016), as well as through structured individual interviews.

For the second phase, the first author encouraged Daisuke to reflect on the FCG meetings and his leadership experiences in weekly advising sessions.

The third phase involved Daisuke leading the FCG meetings. Subsequently, after each FGC meeting, Daisuke completed an online questionnaire individually (see Appendix B).

At the end of the semester, the student facilitator (the first author) helped Daisuke reflect on his leadership experience and provided guidance on how future FCG leaders could further develop autonomy-supportive behaviors, through a structured interview and the WLL.

At the beginning of the new academic year (April 2023), we approached Daisuke, explained the new research project, and provided a consent form outlining his participation. This included details about the project’s duration and the anonymization of his responses. Daisuke’s involvement was voluntary and encompassed weekly advising sessions, a weekly online questionnaire, a structured interview, and the use of the WLL.

The 11 weekly advising sessions, conducted in French, lasted 45 minutes each and took place one day before the FCG meetings. During these sessions, the leader reflected on his experience as a leader. Although no audio recordings were made at the participant’s request, the first author took notes, which the participant reviewed for accuracy.

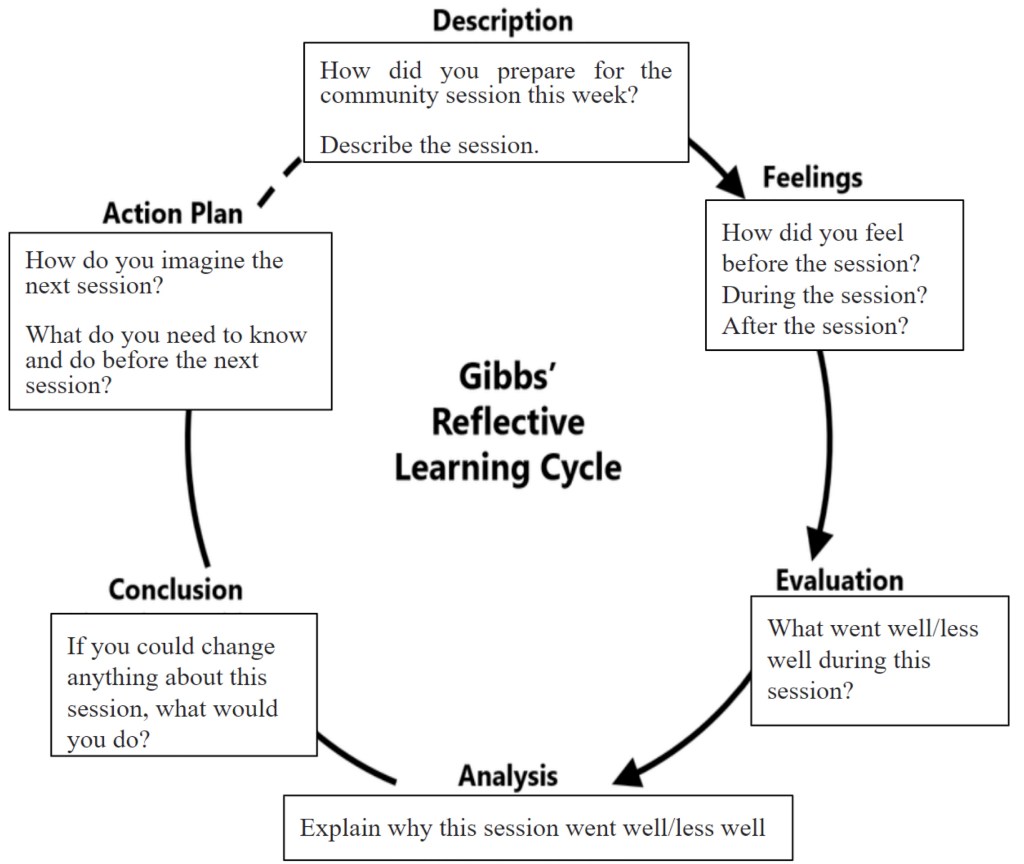

Daisuke completed the online questionnaire after seven FCG community meetings between April and June 2023 (see Appendix A). Adapted from Gibbs’ reflective cycle (1988), the questionnaire aimed to foster reflection on action, derive meaning from experiences, and identify areas for improvement. The questions covered various aspects of the meetings: preparation, Daisuke’s feelings before, during, and after, positive and negative aspects, suggestions for improvement, and next steps (Figure 3). The questionnaire was written in Japanese and French, with Daisuke choosing to respond in Japanese for six entries and in French for one.

At the end of the first semester of 2023, the leader participated in a structured 45-minute audio-recorded interview consisting of four topics and 12 items, including his feelings, attitudes, roles, and the resources and skills needed (Appendix C). Additionally, he completed a WLL for the third time.

Figure 3

Weekly Reflective Questions Asked to the FCG Community Leader

Data Analysis

Results consist of different sets of qualitative data that gathered Daisuke’s experience for seven months: LA’s notes of 11 advising sessions, seven entries of the weekly online nine open-ended questionnaire, discussions based on three WLLs, answers to three individual interviews, and one LLH. For analysis, the data was divided into four time periods that correspond to the stages of the Cycle of Autonomy-supportive Learning (Watkins & Hooper, 2023):

- Stage 1: Encouraging reflection about leadership and language learning experiences

- Stage 2: Assisting the leader to reflect on the community and the leadership experience

- Stages 3 and 4: Modeling and reflecting on autonomy-supportive behavior in the community

- Stages 5 and 6: Reflecting on the community and leadership experience and reaching out to the next leader

We first analyzed and interpreted Daisuke’s lived experiences collected in each instrument, focusing on what the leader said. To ensure reliability, we asked him to review our interpretation of his answers for accuracy.

Findings

Being a Co-leader: Encouraging Reflection about Leadership and Language Learning Experiences

Daisuke joined the FCG community in September 2022 and became a co-leader three months later. He took over the role of leader in the following academic year (April 2023). During his first interview, conducted when he became a member and involving a questionnaire, namely the LLH, he primarily discussed effective language learning strategies, emphasizing the importance of communication and practice with fellow students and native speakers, implying his initial motivation to join the FCG and what he expected to gain from it.

A second interview, which included an adapted version of the WLL, was conducted at the end of his first semester as an FCG member and after a month as a co-leader in January 2023. The WLL reveals that the community’s structure and the leadership decisions, with his help, met his initial expectations of improving his French speaking skills with others, despite some difficulties in understanding and participating actively in discussions at the beginning. Furthermore, his involvement as a co-leader not only boosted his self-confidence but also spurred him to utilize diverse resources for language learning. Reflecting on his experience, Daisuke expressed a more positive outlook on assuming leadership roles, stating, “I’m a little bit nervous. But a lot of members agree with my opinion. So I feel so happy.” He also proposed improvements for the community, such as organizing activities outside the SALC and enhancing collaboration with members of diverse backgrounds.

Starting off: Assisting the Leader to Reflect on the Community and the Leadership Experience

In the first month of his leadership, Daisuke mentioned that the weekly advising sessions with the LA were highly beneficial in helping him gain a deeper understanding of his roles and make more deliberate decisions regarding the community, specifically the structure of the weekly FCG meetings. In the first week, he took proactive steps to promote the community, such as redesigning the FCG poster, participating in the SLC event organized by the SALC, and engaging with students in Japanese and English about the FCG while walking around the facility with the LA.

Furthermore, according to the leader’s comments, the LA helped him resolve issues encountered during his time as a member and observed while serving as a co-leader, including the lack of opportunity to prepare the conversation topics in advance, which affected his capacity to engage with more proficient members. To address this, Daisuke divided the members into two groups, depending on their level of proficiency (intermediate/advanced and beginner) and assigned different conversation topics to each group. Prior to each weekly FCG meeting, he collaborated with the student facilitator to design and distribute a poster with the conversation topics (in Japanese and French) via an application for instant communication. Regarding the groups’ mechanics, inspired by his language teachers’ methods for fostering speaking practice in class, Daisuke allocated 30 minutes of speaking time in total. For the intermediate/advanced group, he divided this time into five segments: five minutes for reviewing the vocabulary related to the weekly topic and four times five minutes for small group discussion. Additionally, he enlisted the help of a native speaker member, Diane, to provide mini-classes for the beginner group.

While the leader always had ideas for topics for the intermediate/advanced members, based on the calendar (e.g., Describe how people spent the national holiday in your country, in the second FCG meeting on May 12th after the Golden Week, a week-long holiday in Japan) or his interests (e.g., What do you do in your free time?, in the fourth FCG meeting on May 26th), he encountered difficulties in selecting topics for the beginner mini-classes. This challenge stemmed from the fact that beginner-level membership fluctuated weekly, and beginner members were less regular in attendance. In response, after consulting with Diane and Emily, Daisuke prioritized reviewing content covered in the first two meetings (greetings and basic daily objects) for FCG meetings 3 and 4.

Concerning Daisuke’s impressions of the first four community meetings, comments collected in the weekly questionnaire and end-of-semester interview indicated that he experienced less nervousness with time and started to feel more comfortable with his roles and position by the end of the first month (“I didn’t really like this position because I was stressed and I didn’t speak well either”, interview). Daisuke’s evaluation and analysis of the FCG meetings indicated that the community’s success and his confidence as a leader were closely tied to his language proficiency and ability to communicate effectively with all members (“I could convey my opinion and enjoy the conversation with different students”, second FCG meeting). He also found validation in others’ approval of his leadership attitudes (“Did you think: ‘You have to relax, you have to stop stressing?’ No, it was another member who told me that”, interview) and position (“A member asked me whether he should join the intermediate or beginner session. I was surprised he asked me”, third FCG meeting), and then aligned with the increasing number of members, especially the attendance of beginners (“I want to make it a community where even the beginners can feel free to join”, third FCG meeting) and their level of satisfaction and participation (“Members seemed relaxed when talking to each other. It is the image of the community I was targeting”, fourth FCG meeting), including the help received from some members to perform a task the leader felt unable to (“I was grateful that the teacher organized a beginners’ session […] I can’t teach well for beginners, so it’s best to ask the native teacher”, interview). His individual reflections concerning the upcoming weekly FCG meetings, including the skills and knowledge to acquire, mirror the above comments about improving his French proficiency, listening to the members’ opinions, and encouraging beginners to join the community.

Gaining Confidence: Modeling and Reflecting on Autonomy-supportive Behavior in the Community

In the second month of his leadership, Daisuke implemented changes to better prepare and manage the weekly community meetings. After consulting with some student members and the LA, he decided to use online resources to find conversation topics for the fifth and sixth FCG meetings. He also reached out to native-speaker members to share their francophone cultural knowledge (e.g., the seventh FCG meeting about Madagascar) and administration staff assisting him in participating in one of the SALC events (International Language Festival, Dialogue at a Parisian Cafe). Furthermore, Daisuke highlighted the importance of maintaining regular communication with the community between meetings to boost members’ motivation and update absentees on activities. As a result, he voluntarily took and shared pictures of meetings featuring cultural knowledge presentations mentioned above in the FCG Line group. According to him, this initiative positively influenced community attendance.

The leader’s evaluations of the weekly FCG encounters (meetings six, seven, and eight) suggest a more positive impression compared to the first month of leadership, which, according to the LA’s notes, he connected with his ability to anticipate potential challenges and devise solutions, (e.g., “Because of the rain, we had fewer participants. Reviewing content was the best option”, fifth FCG meeting) and to change his way of dealing with a situation he considered negative in the past (e.g., “Fewer members came, which was good after all because they had more opportunities to speak”, sixth FCG meeting). Daisuke’s responses also revealed increased confidence as a leader, particularly in speaking French in front of the community or an audience. This newfound confidence led him to embrace new challenges, including planning and carrying out a mini-class in French with Diane’s help during the eight FCG meeting. Furthermore, he began exploring ways to integrate students from non-English majors into FCG activities and facilitate connections between members majoring in English and International Communication with activities in other departments, such as inviting the community to participate in a school festival through Line messaging.

Passing the Baton: Reflecting on the Community and Leadership Experience, and Reaching Out to the Next Leader

Daisuke was selected for an exchange program abroad, so he could no longer continue as the community leader for the next semester. However, he took proactive steps to find a successor and discussed his reasons with Emily. This shows more independence and self-confidence, contrasting with his initial attitude when he took on the role.

Towards the end of his leadership, Daisuke participated in a final interview where he shared his feelings, attitudes, roles, resources used, and skills developed throughout his leadership journey. Despite initially lacking interest in becoming a leader when he was a co-leader, as mentioned earlier, he grew to value the role and wished to have been able to continue. He found the experience of transitioning from a member to a co-leader, then to a leader, and finally to a mentor enriching. When asked about the use of resources in the community, in the final interview, Daisuke emphasized the importance of involving intermediate students in assisting beginners to maximize the utilization of native French speakers for conversation. He stressed the significance of natural communication with native speakers within the community. Regarding his personal growth, Daisuke highlighted an increase in confidence, development of social skills, and greater comfort in advising peers. He recognized the importance of organizational skills for a leader but believed that these skills could be acquired over time. Additionally, he mentioned that learning French had become enjoyable for him, attributing this positive shift to his involvement in the community and his leadership role, which allowed him to appreciate language learning and practice more.

To the question, “What could you recommend to the next leader in terms of skills to develop or use?”, he emphasized the importance of ensuring beginners feel welcome and comfortable joining the community. He suggested being proactive in recruiting new members through advertising and effectively managing different skill levels to facilitate growth within the community. Furthermore, he noted that having a high French proficiency level doesn’t necessarily equate to better leadership and advised his successor not to stress, emphasizing the importance of maintaining a fun and informal atmosphere. Daisuke also mentioned that he had begun delegating some responsibilities to his successor.

At the end of the final interview, Daisuke completed a WLL, a tool he filled out twice already (see Appendix A for the dates). Figure 4 shows a summary of the three WLLs completed by Daisuke and illustrates how participating in the FCG weekly meeting for two semesters, as a member (blue line), co-leader (orange line), and leader (gray line) impacted 12 different aspects of his French learning journey. Daisuke demonstrated growth across all areas of the wheel, with notable improvements in confidence, motivation, collaboration, and understanding of francophone cultures. The leader outlines the importance of cultural aspects in the community: “Speaking a language is also connected to knowing and experiencing the culture of the country or countries”. It can be inferred that his leadership role fostered personal development, while his participation contributed to his cultural and linguistic proficiency as a French learner.

Figure 4

WLL Completed by the Leader at Three Different Stages

Discussion

The findings provide insights into the experiences of a leader of a student-led language group to help understand what and how the decisions were made and what it revealed about his leadership style.

Results indicate that the regularity and continuity of the reflective (inner) dialogue about the leader’s roles and responsibilities, facilitated by the LA and the different tools provided, supported him greatly in taking proactive steps to foster a community environment that welcomes French speakers with different profiles and listens to and answers members’ needs, concerns, and interests. The narrative inquiry documents different stages in Daisuke’s journey of leadership.

Completing the LLH and a WLL with the help of a LA as a co-leader seems to have contributed to observing his strengths and weaknesses and getting a deeper understanding of his identity as a multilingual speaker and his expectations towards the FCG community. Additionally, as observed in Watkins and Hooper’s handbook (2023), such information allows the student facilitator to construct a dialogue that better suits the student leader’s personality and the future challenges he is willing to face.

During the first and second months of his leadership, the leader’s impressions showed that he increasingly felt more confident in his leading position, accepted as a leader by the community, connected to the members as well as their needs and expectations, confident in making decisions for the group and being able to take on new challenges, suggesting that he fulfilled, to a certain degree, his Basic Psychological Needs described in Ryan and Deci (2017) and considered essential to building an autonomy-supportive community and sustain motivation and engagement (Watkins & Hooper, 2023), as Table 2 illustrates.

Table 2

Basic Psychological Needs in Daisuke’s Leadership Experience

Furthermore, Daisuke’s comments indicate that his decisions were gradually less focused on his needs as a member of the community and more fostered on improving the members’ motivation, well-being and ownership. Mostly based on observations he made as a co-leader and leader during the FCG meetings and members’ comments and facilitated by the advising sessions and the weekly questionnaire. His initiatives included diversifying membership, restructuring speaking practice sessions, enhancing communication, and organizing cultural events, aligning with common community leader tasks outlined by Tarmizi et al. (2006, as cited in Watkins & Hooper, 2023). Furthermore, the roles undertaken, the tasks performed, as well as the decisions made indicate that Daisuke gained self-awareness and improved his ability to understand and interpret members’ needs based on their emotions and reactions during the FCG meetings. This suggests that his leadership style (based on Goleman’s descriptions, 2000 – See Table 1 for the description of each leadership style) has evolved progressively too, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3

Daisuke’s Behavior Suggesting Leadership Styles

When Daisuke was ready to pass the baton to the future leader, his answers suggest that he had grown more relaxed and confident. Having experienced four different roles in the community also seemed to have given him different viewpoints and insight into what is important for each member, whether in a leadership position or not. This echoes the outcomes detailed by Watkins & Hooper (2023), where the leader eventually becomes an autonomy-supportive leader contributing to the community’s sustainability. Furthermore, broadening his horizons through the discovery of the francophone world made him more aware of the language’s evolution and its diverse cultures, making him realize his knowledge of French could be useful in several countries and contexts, reinforcing his motivation while also contributing to giving the community an even more international atmosphere.

Conclusion

This narrative approach followed the journey of a SCL leader, who first took on the role of co-leader alongside the former leader. Findings show that while he first lacked confidence and believed good language skills were the primary sign of being a good leader, he grew more confident and gained autonomy as a learner, a member of the community, a leader and a person. By the end of his leadership, he seemed to have gained insight not only into the French language itself but also into the cultures it is associated with, and he felt capable of advising and mentoring his replacement, nurturing a confident side of his personality.

This study reveals that a leader grows on a personal level through this experience, with the help of the LA and teacher, which affects the community positively as students take turns fulfilling this role and helping each other. The student leader advised his replacement, who took charge of the community in the fall semester. She followed some of the advice given to her, and each leader’s influence over the continuity of the community can be felt. She also welcomed a focus on francophone cultures and continued to implement different levels and topics in an even more structured manner than previously. Each leader has contributed to laying the foundations of the community, which each new leader continues to build on.

The present study focused on one leader, which allowed us to gain insights into the role of a leader in a specific community. However, the accumulation of leaders greatly impacts the community as they contribute differently. Furthermore, following a leader over a longer period or several leaders of different SCLs simultaneously could enrich and mitigate the results of this study. Therefore, to learn even more about a leader’s journey and growth, it would be interesting to focus on more leaders of communities in future research. While the tools used were adequate, a separate questionnaire focusing on the changing roles, especially when going from co-leader to leader or when passing the baton, could have provided more evidence of the leader’s personal growth and his attitudes towards his leadership at different stages.

Notes on the Contributors

Emily Marzin is a learning advisor and a lecturer at Kanda University of International Studies, Japan. She completed a master in didactics at Jean Monnet University and an EdD at The Open University. Her research interests are self-directed learning and intercultural communication.

Diane Raluy has been working as an EFL lecturer for over ten years in France and Japan teaching a wide range of students from early education to university. She received a Master’s degree in language didactics. She is interested in integrating online tools in the classroom, learner autonomy, and advising.

References

Atkinson, R. (1998). The life story interview. Sage publications.

Bandura, A. (2008). Toward an agentic theory of the self. In H. W. Marsh, R. G. Craven & D. M. McInerney (Eds.), Self-processes, learning, and enabling human potential: Dynamic new approaches (pp. 15–49). Information Age Publishing.

Bibby, S., Jolley, K., & Shiobara, F. (2016). Increasing attendance in a self-access language lounge. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(3), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.37237/070306

Castillo Zaragoza, D. (2010). Identity, motivation and plurilingualism in SACs. In G. Murray, A. Gao, & T. Lamb (Eds.), Identity, motivation and autonomy: Exploring their links (pp. 91–106). Multilingual Matters.

Fukuba, S. (2016). My critical thoughts on the English café and the L-café. In G. Murray & N. Fujishima (Eds.), Social spaces for language learning: Stories from the L-café (pp. 105–109). Palgrave Macmillan.

Gao, X. (2009). The ‘English-corner’ as an out-of-class learning activity. ELT Journal, 63(1), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccn013

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: from theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing. Oxford Polytechnic.

Goleman, D. (2000). Leadership that gets results. Harvard Business Review, 78(2), 78–90. https://hbr.org/2000/03/leadership-that-gets-results

Hino, Y. (2016). The dark side of L-café. In G. Murray & N. Fujishima (Eds.), Social spaces for language learning: Stories from the L-café (pp. 100–104). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-53010-3_13

Hollinshead, E. (2022, November). The role of a self-access learning center for non-English-language majors [Paper presentation]. Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education (RILAE), 9th LAb session.

Hooper, D. (2020). Modes of identification within a language learner-led community of practice. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 11(4), 301–327. https://doi.org/10.37237/110402

Hughes, L. S., Krug, N. P., & Vye, S. L. (2012). Advising practices: A survey of self-access learner motivations and preferences. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(2), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.37237/030204

Kanai, H., & Imamura, Y. (2019). Why do students keep joining Study Buddies? A case study of a learner-led learning community in the SALC. Independence, 35, 3–34.

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge.

Kimball, L., & Ladd, A. C. (2004). Facilitator toolkit for building and sustaining virtual communities of practice. In P. M. Hildreth & C. Kimble (Eds.), Knowledge networks: Innovation through communities of practice (pp. 202–215). Idea Group Publishing

Lamb, M. (2011). Future selves, motivation and autonomy in long-term EFL learning trajectories. In G. Murray, X. Gao, & T. Lamb (Eds.), Identity, motivation and autonomy: Exploring their links (pp. 177–194). Multilingual Matters.

Lai, C. (2015). Perceiving and traversing in-class and out-of-class learning: Accounts from foreign language learners in Hong Kong. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 9(3), 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2014.918982

Marzin, E., Hall, M., & Hayashi, C. (2023, October 21). Tandem language exchange: Listening to users’ voices [Conference presentation]. JASAL, Gifu, Japan.

Marzin, E., & Raluy, D. (2023, May 12-14). Student-led language community: Collaborative and beyond-class learning [Conference presentation]. PanSIG, Kyoto, Japan.

Mercer, S. (2012). The complexity of learner agency. Apples, Journal of Applied Language Studies, 6(2), 41–59. https://apples.journal.fi/article/view/97838

Miyahara, M. (2015). Emerging self-identities and emotion in foreign language learning. Multilingual Matters.

Murphey, T. (1998a). Language learning histories I. South Mountain Press.

Murphey, T. (1998b). Language learning histories II. South Mountain Press.

Murphey, T. (2005). Language Learning Histories III. South Mountain Press

Murray, G. (2014). The social dimensions of learner autonomy and self-regulated learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(4), 320–341. https://doi.org/10.37237/050402

Murray, G., Fujishima, N., & Uzuka, M. (2014). The semiotics of place: Autonomy and space. In G. Murray (Ed.) Social dimension of autonomy in language learning (pp. 81–99). Basingstoke.

Murray, G., & Fujishima, N. (2016). Social spaces for language learning: Stories from the L-Café. Palgrave.

Murray, G. (2017). Autonomy and complexity in social learning space management. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.37237/080210

Mynard, J., Burke, M., Hooper, D., Kushida, B., Lyon, P., Sampson, R., & Taw, P. (2020). Dynamics of a social language learning community. Multilingual Matters.

Mynard, J., Ambinintsoa, D. V., Bennett, P. A., Castro, E., Curry, N., Davies, H., Imamura, Y., Kato, S., Shelton-Strong, S. J., Stevenson, R., Ubukata, H., Watkins, S., Wongsarnpigoon, I., & Yarwood, A. (2022). Reframing self-access: Reviewing the literature and updating a mission statement for a new era. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 13(1), 31–59. https://doi.org/10.37237/130103

Reinders, H., & Cotterall, S. (2001). Language learners learning independently: How autonomous are they? Toegepaste Taalwetenschappen in Artikelen, 65(1), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1075/ttwia.65.09rei

Reinders, H., & Benson, P. (2017). Research agenda: Language learning beyond the classroom. Language Teaching, 50(4), 561–578. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0261444817000192

Rubio, F. (2014). Self-access language learning centers: A comparative analysis in language learning in higher education. In S. Mercer & M. Williams (Eds.), Multiple perspectives on the self in SLA (pp. 41–59). Multilingual Matters.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory. Basic psychological needs in motivation, development and wellness. Guilford Press.

Thornton, K. (2022, November). Languages other than English (LOTE) in Japan: What support are SALCs providing? [Paper presentation]. Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education (RILAE), 9th LAb session.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky. Plenum Press.

Watkins, S. (2021). Becoming autonomous and autonomy-supportive of others: Student community leaders’ reflective learning experiences in a leadership training course. JASAL Journal, 2(1), 4–25.

Watkins, S. (2022). Creating social learning opportunities outside the classroom: How interest-based learning communities support learners’ basic psychological needs. In J. Mynard & S. J. Shelton-Strong (Eds.), Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom: A self-determination theory perspective (pp.109–129). Multilingual Matters.

Watkins, S. & Hooper, D. (2023). From student to community leader: A guide for autonomy-supportive leadership development. Candlin & Mynard.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Harvard Business School Press.

Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). An introduction to communities of practice: A brief overview of the concept and its uses. https://www.wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice

Wenger-Trayner, E., Wenger-Trayner, B., Reid, P., & Brudelein, C. (2022). Communities of practice in and across organizations: A guidebook. Social Learning Lab.

Wongsarnpigoon, I., & Watkins, S. (2022, November). An event for embracing linguistic diversity in a self-access center [Paper presentation]. Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education (RILAE), 9th LAb session.

Yamashita, H. (2021). JASAL student conferences: Providing opportunities for students to learn and grow together. JASAL Journal, 2(2), 52–59.

Appendices – See PDF version