Luu Thi Mai Vy, Ho Chi Minh City University of Economics and Finance, Vietnam

Lu Jinming, Guizhou Qiannan Economic College, China

Luu, T. M. V., & Lu, J. M. (2024). Are Chinese university students ready for autonomous English listening practice? Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(3), 443–461. https://doi.org/10.37237/202403

First published online, 31st July, 2024.

Abstract

Given the growing emphasis on autonomous learning within language education, comprehending students’ perspectives, incentives, and cognizance about autonomous listening becomes imperative for the formulation of effective pedagogical approaches. This study seeks to examine the readiness of Chinese university students to engage in autonomous English listening practice. The research employed a questionnaire-based methodology administered to a sample of 200 Chinese university students. The survey focused on gauging students’ perspectives on autonomous English listening practice, examining their level of motivation, and assessing their awareness of their capabilities in handling autonomous listening. The study revealed that Chinese university students generally recognize the prospects and promises of autonomous English listening. Notably, students exhibited increased motivation for autonomous listening provided that they were given teacher guidance and a certain level of pressure. Additionally, the findings indicated that students possess a relatively high level of awareness regarding their capabilities to engage in autonomous listening practices. This research contributes to the literature on language education by providing insights into the readiness of Chinese university students for autonomous English listening practice. The identified factors influencing motivation and awareness shed light on the potential success of implementing autonomous listening strategies. Educators and policymakers can benefit from these findings to enhance English listening instruction methodologies and better meet the needs of students in the ever-evolving landscape of language education.

Keywords: autonomous listening; readiness; Chinese EFL learners

The advancement of technology has opened up new avenues for cultivating autonomy, facilitating learners’ easy access to information, tools, and environments that enhance autonomous language learning, particularly in the development of listening abilities. Autonomous listening is seen as liberating learners from the constraints of the classroom and teachers’ control over listening input. Instead, learners exert more control over their listening experiences outside the classroom, determining the pace, time, and location.

With the opportunities for autonomous listening, learners come to recognize the importance of decision-making, sustained effort, commitment, and motivation to achieve language skills (Lau, 2017). Moreover, promoting autonomous listening serves as a means of raising learners’ awareness and fostering the ability to become lifelong independent learners. Bringing metacognitive knowledge to light, for example, enables students to organize, track, and assess their implicit listening processes (Bozorgian et al., 2022). Furthermore, a literature review has revealed that autonomous listening benefits learners in various aspects of language improvement. Students not only enhance their aural comprehension but also experience improvements in other domains such as vocabulary, speaking, and overall learning engagement (Cross, 2014; Hidayati et al., 2021; Katchen, 1995 ).

Simultaneously, most Chinese colleges and universities place significant emphasis on the intensive training of students’ listening, speaking, reading, writing, and translation skills, setting grade requirements for English proficiency, such as the College English Test Band 4 and Band 6. A key policy directive encourages the utilization of information technology as a medium in English courses, aiming to continually enhance teaching methods and expand students’ learning avenues (Liang, 2021). This approach liberates English teaching and learning from specific situations, freeing it from the constraints of time and space. Notably, the integration of technology into listening practices extends beyond the traditional classroom setting, addressing the challenge of limited time allocated for listening (Wang, 2020). Moreover, autonomous listening serves to diminish the influence of teachers’ dominance and manipulation in teaching listening, recognizing it as an individual process requiring personal effort, pace, and interpretation.

A body of literature has demonstrated the potential of technological resources in cultivating autonomy in language learning (Cheng & Lee, 2018; Vu & Shah, 2016; Yan & Xiaoqing, 2009; Yu, 2023), particularly in the domain of L2 listening (Chen, 2016; Cross, 2014; Yang, 2021). These researchers have highlighted the significance of fostering autonomy to support learners in building lifelong learning capacities and pursuing independent study outside the classroom. The findings of these studies also underscore a high level of reliance on teachers by students in the context of listening development. As emphasized by Chen (2016), the success of independent learning hinges on the students’ attitudes. Additional factors affecting Chinese learners’ autonomous listening were identified, including intangible listening improvements and a lack of motivation stemming from low English proficiency (Yao & Li, 2017).

Meanwhile, Armenakis et al. (1993) posit that readiness is the cognitive precursor to behaviors either opposing or supporting a transformative endeavor. In this context, the readiness of English language learners for a shift from traditional listening to autonomous listening is crucial for its successful implementation. Consequently, gauging the level of readiness for autonomous listening will indicate students’ willingness, motivation, and ability to engage in listening tasks (Razali et al., 2018). Moreover, the level of readiness is subject to change over time due to the growing demand for digital language learning. Therefore, more rigorous research is needed to gain a comprehensive understanding of learners’ readiness at a specific point in time. In light of the necessity to address the significance of students’ readiness for autonomous listening, the study seeks to answer the following research questions:

- What are learners’ attitudes towards autonomous listening?

- How motivated are students for autonomous listening?

- How do students self-evaluate their abilities for autonomous listening?

Literature Review

Autonomous Listening

Cotterall (1995) contends that autonomy is preferable for pedagogical, practical, and philosophical reasons. First and foremost, students are entitled to make decisions about their education as they prepare for a rapidly changing future where independence is crucial for contributing to society. Second, when students are consulted on aspects such as the pace, order, style of instruction, and course materials, they gain confidence in their learning. Finally, since teachers may not always be accessible, students must cultivate the ability to study independently. In this context, autonomy in listening becomes inevitable due to the individualized nature of the listening process and the pressing need for educational transformation in a digitalized era.

Listening, described as a cognitive process influenced by the interplay between internal and external variables (Field, 2009), faces challenges in meeting the needs of an increasing student population. Achieving acceptable aural comprehension requires tailored listening practices, which are impossible without technological implementation. For example, providing personalized feedback relies on automatic and corrective features achievable only through technology. Vu et al. (2022) emphasize that technology-driven autonomous listening environments have the potential to address the challenges of large-sized language classrooms and teachers’ limitations in meeting individual student needs in the absence of the teacher. Furthermore, the explosion of data and information technology serves as valuable resources for developing listening skills, a factor that should not be overlooked by both language learners and educators.

Some language researchers may inquire whether autonomous listening constitutes a form of extensive listening. According to Chang (2018), extensive listening involves deliberate exposure to massive amounts of comprehensible and enjoyable aural input disseminated through television, radio broadcasts, digital platforms, and online resources. The goal of extensive listening is to facilitate the development of automaticity in recognizing spoken language and to cultivate enjoyment of listening comprehension (Chang, 2018; Chang et al., 2019). In contrast, autonomous listening, as noted by Cross (2014), involves learners engaging in listening activities beyond the confines of the traditional classroom environment. They independently decide the timing and location of their interaction with audio content at their own volition, whether in physical or virtual self-access centers. Rost (2016) argues that extensive listening refers to listening continuously for extended periods within the target language, typically with overarching objectives of cultivating an enduring appreciation and acquisition of the materials. He differentiates autonomous listening as independent listening without the direct involvement of an instructor. He stresses that learners control the selection of input, task completion, and assessment. Based on Rost’s (2016) categorization, autonomous listening includes extensive listening. Despite nuanced disparities in their scopes and types of activities, both autonomous and extensive listening offer significant benefits for language learners in developing listening skills by emphasizing the listeners’ independence and flexibility.

In this study, autonomous listening fundamentally refers to the mode of listening in which students practice outside the classroom without teachers’ manipulation. The emphasis is on the absence of the teacher, whether this listening completely replaces the traditional classroom-based approaches or complements them. In some contexts, autonomous listening can be understood as self-directed or self-regulated listening. Such listening entails a transformation in the roles of both learners and teachers, as the operation of listening practice places more responsibilities on learners. In essence, learners need to possess additional learning and listening strategies to navigate autonomous listening. This is exemplified by Smith’s argument (2005), stating that the effectiveness of resource-based learning with flexible delivery critically depends on self-direction. Conversely, teachers are responsible for supervising students, assessing their language needs, and evaluating their readiness for independent study. According to Voller (1997), teachers serve as facilitators, offering psycho-social and technical support when necessary, and as counselors, providing consultation and guidance. Voller (1997) emphasizes that teachers are valuable resources in helping learners use materials efficiently, skillfully, and proactively. Moreover, he underscores that with autonomous listening, the power of the student rises concurrently with the decline of the teacher.

In addition to changes in the roles of learners and teachers, autonomous listening is characterized by underlying mechanisms embedded in a listening protocol. These mechanisms reflect theoretical underpinnings such as the nature of the listening process and feedback provision. For instance, Vu et al. (2022) identify crucial principles for the instructional design of an original listening platform, including respecting listeners’ meaning-making processes, providing accurate feedback, guaranteeing the quality of listening input, and more. These guidelines aim to create effective, efficient, and engaging learning experiences. Due to these characteristics, learners will encounter multiple types of listening situations, varying according to the listening environment. Therefore, examining learners’ readiness for autonomous listening has always been an integral part of the process of replacing the classroom-based, teacher-led listening approach.

Readiness for Autonomous Listening

Due to increasingly dynamic environments, organizations are consistently compelled to change to enhance their systems or operations, as noted by Armenakis et al. (1993). A crucial determinant of the success of any new implementation is the readiness for change. In this context, readiness, as defined by Armenakis et al. (1993), is, “the cognitive precursor to the behaviors of either resistance to, or support for, a change effort” (p. 681). Similarly, comprehending the concept of readiness in educational settings, where conventional teaching approaches may be replaced, is essential for assessing its feasibility. Specifically, addressing students’ resistance to a particular approach can be coupled with assessing their readiness for it.

Lin and Reinders (2018) categorize readiness for autonomy into three aspects: psychological, behavioral, and technical readiness, which are aligned with the three dimensions of autonomy described by Benson (1997). Psychological readiness pertains to the degree to which students express willingness and confidence in taking responsibility for their education. Behavioral readiness is the extent to which individuals actively engage in autonomous learning practices, while technical readiness involves possessing the appropriate knowledge and abilities required for autonomous learning. In their investigation of 66 students, Lin and Reinders (2018) found that while students seemed behaviorally or technically prepared for autonomy, they did not seem psychologically prepared. Their high enthusiasm and confidence in taking responsibility for their learning did not correspond to their reported abilities to control their learning. The primary constraint to autonomy was identified as a lack of teacher assistance.

Concerning autonomous listening, Razali et al. (2018) define it as the degree to which an individual possesses the attitudes, abilities, and personality traits required for effective listening. Assessing students’ preparation for autonomous listening will reveal whether they are ready, motivated, and capable of participating in listening assignments. Other researchers (Chu & Tsai, 2009; Lee et al., 2017) also argue that higher-ready learners exhibit more confidence, determination, and inclination to take charge of their educational journey by exercising self-control and self-management throughout the entire learning process.

Previous Studies

Fostering autonomy in language learning has drawn significant attention from scholars. Yan and Xiaoqing (2009) conducted a study involving 345 English language learners, revealing positive views toward computer-assisted autonomous language learning among Chinese college students. However, despite the favorable attitudes, the perceived difficulties in using technology outside the classroom resulted in a lower frequency of computer-assisted behaviors. The findings underscore the ultimate goal of encouraging autonomy-to support students in becoming aware of and capable of lifelong learning and independent study. Razieyeh (2012) measured the level of readiness for autonomous self-access language learning among 133 Iranian students. The results unveil that while students appear to be prepared to assume greater accountability and control over certain areas of their education, they still require guidance and oversight from their teachers in other areas.

Similarly, the factors influencing the continuation and suspension of English language study in relation to a group of tertiary language learners enrolled in a self-directed language learning scheme at an English-medium institution in Hong Kong are examined by Cheng and Lee (2018). The research employed a mixed-methods approach, collecting and analyzing both quantitative and qualitative data. Twenty-seven students participated in the program and finished the online questionnaire; however, only 21 gave their approval to participate in the one-on-one interviews. The study demonstrates that peer and advisor support play a role in students’ perseverance. When it comes to self-directed language learning activities, motivated learners tend to be more engaged than less motivated ones. It appears that driven learners wanted greater autonomy in their education, whereas less motivated learners preferred more guidance and nurturing; as a result, the latter group opted to participate in activities that required an authoritative figure from the teacher. In a recent study, Yu (2023) investigates how English language learners with varying skill levels use technology-enhanced language learning in their practice outside of the classroom. The research used a mixed-method methodology, with a focus on both quantitative and qualitative components. Research consent was obtained from 52 students in advanced-level classes and 47 students in beginner-level classes. With a focus on how competence levels affect the amount of autonomous technology utilized for language learning, the study improved our knowledge of how English language learners use technology on their own. Despite having varying degrees of proficiency, the students felt similar about their use of technology for language acquisition. Higher competence and more enthusiastic language learners would self-direct their use of technology for language learning by participating in a wider variety of activities. The findings showed that there was no correlation between students’ competency levels and their usage of independent technology for language learning. Almost one-third of the students did not use technology for independent English learning outside of the classroom.

In the domain of listening, more attention has also been given to autonomous practice. In an exploratory case study, Cross (2014) detailed how a Japanese student learning English as a foreign language was exposed to metatextual skills and activities for metacognitive instruction. The goal was to encourage the students’ independent use of the BBC’s online “From Our Own Correspondent” podcasts outside of the classroom to improve the student’s listeningcomprehension in Spanish. By investigating how providing direction and feedback on metatextual abilities and elements of metacognitive teaching affects an L2 listener’s autonomous use of podcasts, this case study offers pedagogical insights into fostering independent listening growth outside of the classroom.

Vu and Shah’s (2016) investigation sought to discover what teachers and students do in self-directed learning (SDL) to learn English listening skills, as well as strategies to enhance the effectiveness of students’ SDL. Ten teachers and 192 second-year students participated in the study. The findings of this research show that the majority of teachers believe that it is not essential to give students more guidance when it comes to their SDL, while students place clear instructions on how to learn English listening skills as their primary solution to improve the effectiveness of their SDL.Although teachers value students’ intentions towards in-class learning, they underestimate students’ abilities to learn listening on their own. There is a misalignment between teachers’ and students’ perspectives on the variables that cause students to lack skills in SDL in English listening. According to the findings, teacher participants believe students have poor SDL due to an inadequacy of appropriate assessment methods, students practicing outside of class time, and their ignorance of the vital role of listening skills, whereas students report their perceived inabilities to be effectively self-directed in autonomous listening due to a shortage of motivation, an appropriate learning approach, lexical knowledge, and facilities. Students are not yet prepared to learn on their own.

In the meantime, students’ opinions of the autonomous listening mode were investigated by Yao and Li (2017). In order to complete the listening course outside of the classroom, the students must purchase a well-designed book with a CD attached. Both a questionnaire and a semi-structured interview were used to examine the opinions of Chinese EFL undergraduates regarding the listening autonomous learning mode. The questionnaire survey involved 219 Chinese first-year undergraduates majoring in subjects other than English from one of the best institutions in China.The results indicate that it is significantly more difficult than anticipated for Chinese undergraduates who are not majoring in English to build independent learning skills in English listening. The Chinese context deeply ingrained traditional teacher-dependent learning style impedes the shift toward learners’ autonomous learning. The research clarifies the following factors that affect Chinese learners’ autonomous listening learning behavior and outcome: poor learning experiences, intangible listening progress, lack of self-discipline due to reliance on teachers, and lack of motivation due to the irrelevance of English.

In Chen’s (2016) research, 14 English majors spent their free time participating in one-way, message-oriented transactional listening. It was discovered that the majority of students selected audiovisual resources to watch, with TED lectures being the most popular option. The two most common listening problems that they noted in their diaries were speed and unfamiliar terminology. The results of this study, which record students’ self-reports on a variety of listening materials, perceived listening challenges, and perceptions of keeping a listening diary, contribute to the understanding of students’ autonomous, outside-of-classroom L2 listening. In the digital age, students must be guided to be more adaptable in their resource selection. The findings show how listening diaries can be used to reveal the process of students’ private listening. Keeping a listening journal enhances students’ knowledge of the options available to them as self-directed learners. The attitude of the student is crucial in influencing the effectiveness of independent language learning. To benefit from the vast resources accessible in the digital age, students must take more responsibility for their learning.

In the same vein, Yang (2021) aimed to investigate the independent learning processes and program views of Mandarin-speaking EFL learners. For ten weeks, twenty-two students from a Taiwanese university were chosen to participate in a TED listening program. Before the deadline, they were free to choose how, when, and where to view each TED talk. Each talk’s content was to be reflected upon and listening difficulties were reported in a listening log that they were required to submit later. Interviews and questionnaires were used to gather data. The findings indicate that both contextual and personal factors influenced the autonomous learning processes and that the contextual elements also partially drove the deliberate learning behaviors. Even if students’ involvement dwindled with time, they appreciated having more flexibility than they would have in a classroom and being able to take charge of their learning. These studies collectively contribute to our understanding of autonomous language learning, especially emphasizing the need for adaptable strategies and supportive environments to enhance learners’ autonomy in L2 listening development.

Research Methodology

In this descriptive study, a questionnaire was employed as the data collection instrument because this type of tool allowed researchers to obtain a comprehensive understanding of learners’ attitudes toward and readiness for the implementation of autonomous listening in listening pedagogy. Conducted at one of the public universities in China, the study recruited 200 second-year non-English major undergraduate students (26% male and 74% female) using convenience sampling. The participants, with an average age of 22, represented various disciplines: accountancy (48%), administrative management (25%), and financial management (27%). Despite their diverse backgrounds, they shared nearly identical English learning and proficiency levels based on their latest English test results.

The survey items were adapted and modified from the questionnaire used by Yao and Li (2017), focusing on three main themes: learners’ attitudes towards autonomous listening, their motivation for autonomous listening, and their abilities to conduct autonomous listening. The survey comprised 25 statements, and participants indicated their level of agreement using six options from one to six. The Cronbach’s Alpha for the survey items was 0.92, indicating high reliability. The questionnaire was translated into Chinese after being reviewed by two experts and was piloted with a group of students before its use in the main study. Prior to completing the questionnaire, participants were informed of the research purpose, and their consent was obtained. Most importantly, participants were provided with the definitions of autonomous listening used in this study to ensure they understood the concept and approached all survey items correctly. Data collected were analyzed using SPSS 25, involving the calculation of percentages, means, and frequencies. The range of mean scores on a 6-point Likert scale was interpreted based on the level of agreement or disagreement as follows: 1.0 – 1.8: Strongly Agree; 1.9 – 2.6: Agree; 2.7 – 3.4: Slightly Agree; 3.5 – 4.2: Slightly Disagree; 4.3 – 5.0: Disagree; 5.1 – 6.0: Strongly Disagree.

Results

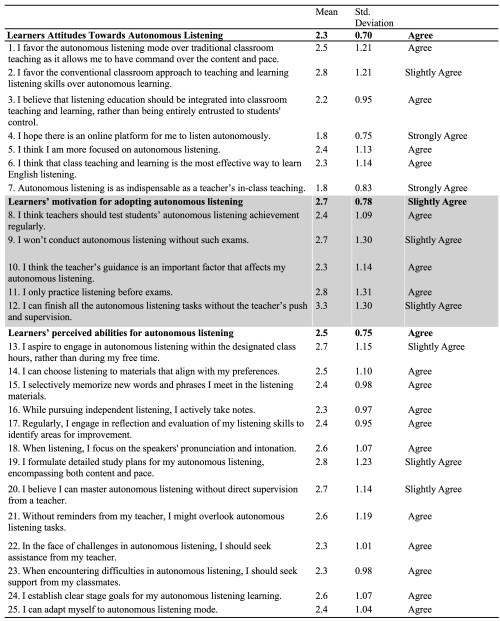

Overall, the students had positive attitudes toward the implementation of autonomous listening (M=2.3, SD=0.70). They also reported a moderate level of motivation for and confidence in their abilities to conduct autonomous listening (M=2.7, SD=0.78 and M=2.5, SD=0.75, respectively), as displayed in Table 1.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics for All the Items in The Questionnaire (N=200)

As regards students’ attitudes, the students showed only a slight preference for traditional listening to autonomous listening with the mean value M=2.8, SD=1.21. In addition, they all were in favor of autonomous listening due to its potential benefits such as giving more control over content and pace, facilitating concentration, and offering a more effective way of listening with the mean value ranging from 2.2 to 2.5. The most striking finding was that while the students showed a yearning for online autonomous listening (M=1.8, SD=0.75), they also stressed the significance of in-class instructions of the teacher (M=1.8, SD=0.83).

In terms of their perceived level of motivation, the students thought how motivated they were for autonomous listening was influenced by the teachers’ assessment (M=2.4, SD=1.09) and teachers’ guidance (M=2.7, SD=1.14). Meanwhile, they admitted that the need for autonomous listening partly relies on external factors like passing examination with the mean ranging from 2.7 to 2.8. Interestingly, a slight agreement was identified among the students concerning the lack of teachers’ pressure and supervision with the highest mean value M=3.3, SD=1.30.

In view of the students’ perceived abilities to conduct autonomous listening, the item receiving the most agreement was related to the plan-making ability with M=2.8, SD= 1.23, whereas the items receiving the least agreement were about peer assistance and instructors when they encountered problems (M=2.3; SD=0.98 and SD=1.01, respectively). Besides, the students also revealed their perceived capabilities in handling autonomous listening with various strategies including material selection, vocabulary learning, self-reflection, notetaking, goal setting, adaptability, and teachers’ consultations. They believed that they could listen autonomously without teachers’ supervision (M=2.7, SD=1.14). However, they also underscored the teachers’ roles in giving reminders (M=2.6, SD=1.19). These confessions seem paradoxical but also understandable.

Discussion

In response to the first question regarding students’ attitudes towards autonomous listening, overall opinions were notably optimistic. Evidently, students recognize the prospects and promises of autonomous listening, explaining their desire for it. This finding aligns with previous studies (e.g., Lau, 2017; Yan & Xiaoqing, 2009; Yang, 2021), indicating that learners value opportunities to control their listening with flexibility. Yan and Xiaoqing’s (2009) research, for instance, revealed positive attitudes toward autonomous listening, although students engaged in it infrequently due to its complexity. This partly explains why students in the current study express a preference for teachers’ guidance in the classroom, even though they are willing to embrace autonomous listening over traditional teacher-led approaches. Additionally, Yu’s (2023) study found that students’ enjoyment played a crucial role in their engagement in self-directed learning. The more enjoyable the tasks, the more effective the outcomes.

Regarding the second research question about students’ motivation for autonomous listening, they acknowledged being motivated when provided with guidance and pressure from teachers. This aligns with Vu and Shah’s (2008) idea that clear instructions enhance students’ effectiveness in autonomous learning. Interestingly, this differs from teachers’ perspectives in Vu and Shah’s research (2008), suggesting a discrepancy in views on the need for guidance. Consistent with these findings, Chen (2016) demonstrated that, in the digital age, students must be led to be more flexible in material selection and assume greater responsibility for their learning. More capable students tend to take more responsibility for their listening (Razieyeh, 2012).

Concerning the third question about students’ self-evaluation of their abilities to listen autonomously, students demonstrated awareness of their capabilities, employing a variety of strategies. Planning was identified as the most salient strategy, highlighting the importance of goal-setting in autonomous listening. This finding resonates with Yao and Li (2017), who identified a lack of self-discipline as an influential factor hindering Chinese learners’ autonomous learning. This tendency may be rooted in a traditional teacher-dependent learning style in the Chinese context. Interestingly, peer support was perceived as the least impactful factor, contrasting with Cheng and Lee’s (2018) findings. This discrepancy may be context-bound and influenced by the interpersonal relationships among students. However, the present outcome corroborates the significant role of instructors found in Cheng and Lee’s research (2018), suggesting that teachers play a crucial role in helping learners develop capacities for autonomous learning. Allowing students to exercise autonomy in listening helps them become more aware of decision-making, personal investment, commitment, and sustaining motivation. Eventually, they become less reliant on teachers and more self-assured in independent listening.

Conclusions

This research aims to assess the readiness of 200 Chinese university students for autonomous English listening practice. Employing a questionnaire-based methodology, the study seeks to gain a comprehensive understanding of students’ readiness across three dimensions: learners’ perceptions, motivation, and perceived capabilities in managing autonomous listening. The results suggest that Chinese university students possess a discerning awareness of the potential advantages associated with autonomous English listening. Notably, students exhibit heightened motivation for engaging in autonomous listening when provided with guidance and a measured degree of academic pressure from teachers. Additionally, the study reveals that students demonstrate a commendable level of self-awareness concerning their abilities to participate in autonomous listening activities.

Drawing pedagogical implications from these findings, several recommendations are proposed to enhance the implementation of autonomous listening in language education. Firstly, it is essential to cultivate positive attitudes towards autonomous listening among both learners and teachers by increasing awareness of its potential benefits, including increased control over content and pace, improved concentration, and a more effective listening experience. Secondly, interventions should be designed to address students’ strengths and weaknesses in managing autonomous listening, focusing on enhancing specific skills such as plan-making, material selection, vocabulary learning, self-reflection, note-taking, goal setting, and adaptability. Notably, the promotion of peer assistance when students encounter problems is encouraged to strengthen collaborative learning skills. Thirdly, considering learners’ preference for online autonomous listening and their perceived significance of in-class instruction and teachers’ pressure and supervision, a balanced approach between autonomy and teacher involvement is recommended. Students should receive the necessary guidance without feeling overly monitored. This guidance may focus on both cognitive and metacognitive strategies as these are essential tools that students can deploy based on their individual learning needs, experiences, and preferences. While cognitive strategies are useful for students to process and understand information, metacognitive strategies can empower students to plan, monitor, and evaluate their listening. The student’s choice between these strategies is not arbitrary but tailored to the unique context of each listener. Finally, teachers should undergo professional development opportunities to acquire the skills and strategies essential for facilitating autonomous listening. This includes understanding the dynamics of online learning, leveraging technology effectively, and adopting learner-centered approaches. By considering these pedagogical implications, language educators can establish a supportive and effective learning environment that harnesses the advantages of autonomous listening while addressing students’ preferences, motivations, and perceived capabilities, gradually replacing the traditional classroom-based listening approach.

Despite its valuable contributions, the study has some limitations. Caution should be exercised in generalizing findings to other contexts and participants due to the modest sample size. Future research endeavors could expand the sample size and encompass participants with varying levels of language proficiency. Another limitation lies in the descriptive nature of the research design, which fails to provide in-depth insights into learners’ opinions regarding the potential of autonomous listening. Moreover, the study did not address the effectiveness of autonomous listening based on learners’ experiences. Empirical research designs could be employed to investigate these effects, offering more robust empirical evidence to support autonomous listening.

Notes on the Contributors

Luu Thi Mai Vy is a lecturer at Ho Chi Minh City University of Economics and Finance, Vietnam. Her research interests include L2 listening development, pronunciation, and CALL. Email: vyltm@uef.edu.vn.

Lu Jinming is a lecturer at GuiZhou Qiannan Economic College, China. Her research interests include L2 listening development, and CALL. Email: 510799772@qq.com

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the students and teachers at the two universities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

References

Armenakis, A. A., Harris, S. G., & Mossholder, K. W. (1993). Creating readiness for organizational change. Human Relations, 46(6), 681–703. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679304600601

Benson, P. (1997). The philosophy and politics of learning autonomy. In P. Benson &

P., Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 18–34). Routledge.

Bozorgian, H., Muhammadpour, M., Mahmoudi, E., & Wallace, M. P. (2022). Embedding L2 listening homework in metacognitive intervention: Listening comprehension development. Frontiers in Education, 7(June), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.819308

Chang, A. C. S. (2018). Extensive listening. The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0564

Chang, A., Millett, S., & Renandya, W. A. (2019). Developing listening fluency through supported extensive listening practice. RELC Journal, 50(3), 422–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/00336882177514

Chen, C. W. (2016). Listening diary in the digital age: Students’ material selection, listening problems, and perceived usefulness. The JALT CALL Journal, 12(2), 83–101. 10.29140/JALTCALL.V12N2.203

Cheng, A., & Lee, C. (2018). Factors affecting tertiary English learners’ persistence in the self-directed language learning journey. System, 76, 170–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.06.001

Chu, R. J. C., & Tsai, C. C. (2009). Self-directed learning readiness, Internet self-efficacy and preferences towards constructivist Internet-based learning environments among higher-aged adults. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 25(5), 489–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2009.00324.x

Cotterall, S. (1995). Developing a course strategy for learner autonomy. ELT Journal, 49(3), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/49.3.219

Cross, J. (2014). Promoting autonomous listening to podcasts: A case study. Language Teaching Research, 18(1), 8–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168813505394

Field, J. (2009). Listening in the language classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Hidayati, A., Hadijah, S., Masyhur, G., & Nurhaedin, E. (2021). Unveiling an Indonesian EFL Student’s Self-Directed Listening Learning: A Narrative Inquiry. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Language, Literature, Education and Culture. https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.9-10-2021.2319469

Katchen, J. E. (1995). Self-directed listening: What student journals reveal. Paper presented a the 29th Annual IATEFL Conference. YORK/ENGLISH/9th– 12th April.

Lau, K. (2017). ‘The most important thing is to learn the way to learn’: evaluating the effectiveness of independent learning by perceptual changes. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(3), 415–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1118434

Lee, C., Seeshing, A., & Ip, T. (2017). University English language learners’ readiness to use computer technology for self-directed learning. System, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.05.001

Liang, W. (2021). University teachers’ technology integration in teaching English as a foreign language: Evidence from a case study in mainland China. SN Social Sciences, 1(8), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-021-00223-5

Lin, L., & Reinders, H. (2018). Students’ and teachers’ readiness for autonomy: Beliefs and practices in developing autonomy in the Chinese context. Asia Pacific Education Review, 11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-018-9564-3.

Rost, M. (2016). Teaching and researching listening. Pearson.

Razali, A. B., Xuan, L. Y., & Abd. Samad, A. (2018). Self-directed learning readiness among foundation students from high and low proficiency levels to learn English language. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 15(2), 55–81. https://doi.org/10.32890/mjli2018.15.2.3

Razieyeh, A. (2012). Readiness for self-access language learning: A case of Iranian students. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(3), 254–264. https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep12/ahmadi/

Smith, P. J. (2005). Learning preferences and readiness for online learning. Educational Psychology, 25(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144341042000294868

Voller, P. (1997). Does the teacher have a role in autonomous language learning? In P., Benson & P., Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 98–113). Routledge.

Vu, D. C., Lian, A. P., & Siriyothin, P. (2022). Integrating natural language processing and multimedia databases in CALL software: Development and evaluation of an ICALL application for EFL listening comprehension. Call-Ej, 23(3), 41–69. https://old.callej.org/journal/23-3/Vu-Lian-Siriyothin2022.pdf

Vu, H. Y., & Shah, M. (2016). Vietnamese students’ self-direction in learning English listening skills. Asian Englishes, 18(1), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13488678.2015.1136104

Wang, L. (2020). Research and practice of reform on college English teaching under the environment of information technology. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 10(4), 453–458. https://www.academypublication.com/issues2/tpls/vol10/04/15.pdf

Yan. G., & Xiaoquing, Q. (2009). Behaviors in Computer-Assisted Autonomous Language Learning. Journal of ASIA TEFL, 6(2), 207. http://journal.asiatefl.org/main/main.php?inx_journals=20&inx_contents=233&main=1&sub=2&submode=3&PageMode=JournalView&s_title=Chinese_College_English_Learners_Attitudes_and_Behaviors_in_Computer_Assisted_Autonomous_Language_Learning

Yang, F. Y. (2021). EFL learners’ autonomous listening practice outside of the class. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 12(4), 328–346. https://doi.org/10.37237/110403

Yao, J., & Li, X. (2017). Are Chinese undergraduates ready for autonomous learning of English listening ? – A Survey on students ’ learning situation. The Journal of Language Teaching and Learning, 7(2), 21–35. https://jltl.com.tr/index.php/jltl/article/view/45

Yu, L. (2023). A comparison of the autonomous use of technology for language learning for EFL university students of different proficiency levels. Sustainability, 15, 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010606