Daniel Hooper, Tokyo Kasei University, Japan

Hooper, D. (2024). Integrating scientific and everyday concepts: Student leadership in a language learning community. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(3), 367–393. https://doi.org/10.37237/150304

Abstract

This study examines the role of everyday and scientific concepts in developing student leadership in a self-access learning center (SALC) in Japan. For this purpose, data from three student learning community leaders and one SALC faculty member participating in an 18-month ethnographic case study of the Learning Group (LG), a student-led learning community within a university-based SALC in central Japan, was reexamined according to a framework informed by concept-based learning. Data was first coded inductively utilizing reflective thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and subsequently deductively using communities of practice theory and the themes of scientific and everyday knowledge. This data highlights numerous ways three leaders of the LG had internalized concepts introduced to them through a SALC-based leadership course administered by a learning advisor (LA) and how this influenced not only their individual learning trajectories, but also the path of their community. Furthermore, the LG leaders were able to develop coherent management/facilitation guidelines for themselves and for future generations of leaders from the social mediation that collaborative group reflection and intentional reflective dialogue afforded. The implications of this study highlight the potential value within SALCs of learning advisors engaging in concept-based instructional approaches where explicit instruction is internalized through dialogic and communicative verbalization and through finding avenues for learners to apply scientific concepts to everyday practice.

Keywords: learning communities, leadership, learner advising, sociocultural theory, concept-based learning

Within sociocultural theory, concepts are cognitive mediational tools that individuals can utilize to solve problems that they can encounter both within the classroom and beyond (Swain et al., 2015). Vygotsky (1986) claimed that higher-level cognitive development is stimulated by the dialectical relationship between everyday concepts–understandings of the world “appropriated indirectly through socialization” (Lantolf, 2011, p. 32) and scientific concepts–systematized, generalizable concepts introduced by an external agent like a teacher. A simple example to illustrate the difference between everyday and scientific concepts is watching plants grow. By watching plants in the sunlight grow more than those in the shade we develop the everyday concept of “plants grow better in the sunlight.” However, by being taught the scientific concepts relating to photosynthesis and how green plants convert light energy into chemical energy stored in glucose, we gain a deeper and more systematized understanding of what we observe everyday.

A number of studies within general education, language learning, and language teaching research highlight the importance of integrating both everyday and scientific concepts in developing individuals’ self-regulation and cognitive development (Brooks et al., 2010; Johnson & Golombek, 2016; Lantolf & Poehner, 2014; Saxe et al., 2015; Swain, et al., 2015). However, due to the central place within the instruction of scientific concepts of a teacher or instructor, much of this research thus far has been conducted in classroom or experimental settings and has focused on areas such as the acquisition of grammatical forms, rhetorical devices in writing, and mathematical or scientific principles. This has meant that the learning of everyday or scientific concepts in out-of-class or self-access learning environments has as yet received scant attention in the existing literature. Self-access language learning is a growing area of interest within higher education in Japan and overseas (Mynard, 2019; Thornton, 2021), with more and more institutions and educators recognizing the potentially valuable role of self-access within a network of language learning settings (Benson, 2017). Despite this growth, however, there remain several problematic issues relating to the accessibility of self-access learning centers (SALCs). This is partially due to the stark differences between SALCs and traditional classrooms and, consequently, the struggles many learners face adapting to SALC use (Hooper, 2023b; Mynard et al., 2020a). One relatively new structure aimed at mediating learners’ transitional difficulties as they enter SALCs is student-led learning communities (Watkins, 2022)–student-created and managed groups that offer scaffolded social learning for SALC users. Student-led learning communities commonly feature a shared area of interest, a mutual responsibility between members, and internally-developed tools or rules (Hooper, 2020b, 2023a; Mynard et al., 2020a). This can be interpreted as congruent with Wenger’s (2010) notion of domain, community, and practice (see Table 1) within a community of practice (CoP). Based on this assumption, in this paper student-led learning communities are regarded as examples of CoPs and, accordingly, I drew upon CoP theory (Wenger, 1998; 2010) as a key element of my conceptual framework for this study.

Table 1

Domain, Community, and Practice in Communities of Practice (Adapted from Hooper, 2023a)

| Domain | Community | Practice |

| Shared competence between members A common interest that members share Common experiences that members bring to the community A common identity that members inhabit or wish to develop | “The social fabric of learning” (Wenger et al., 2002, p. 28) Members building trusting and open relationships by doing things together Members negotiating meaning with one another (Wenger, 1998, p. 73) Positioning of roles in relation to one another | “A set of frameworks, ideas, tools, information, styles, language, stories, and documents that community members share” (Wenger et al., 2002, p. 29) Community-created means of dealing with emergent or recurring issues they face |

For any CoP, the role of leadership is crucial to both sustainability and the degree to which the community is congruent with its stated goals and principles (Saldaña, 2017). Therefore, in this study, I explored the role of everyday and scientific concepts in developing student leadership within a SALC learning community. For this purpose, I analyzed data taken from a previously-conducted 18-month ethnographic case study (Hooper, 2023a) of the Learning Group (LG), a student-led learning community that met on a weekly basis in a university-based SALC in Japan. Although this study draws upon data collected for a larger-scale doctoral study, in the current study I adopt a new theoretical perspective informed by sociocultural theory and focus on an area (concept-based leadership training) unaddressed in the original study. For the current study, I reanalyzed participant observation data from LG meetings, interview data with LG leaders, LG leaders’ language learning histories, and community artifacts, including meeting minutes and promotional materials. Subsequently, utilizing an abductive/hybridized approach to data analysis, I coded data first inductively utilizing reflective thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and subsequently deductively based on CoP theory (Wenger, 2010) and the themes of scientific and everyday knowledge. The research question that I examined for this study was as follows:

In what ways did the LG’s leadership practices integrate everyday and scientific concepts?

Literature Review

Everyday and Scientific Concepts

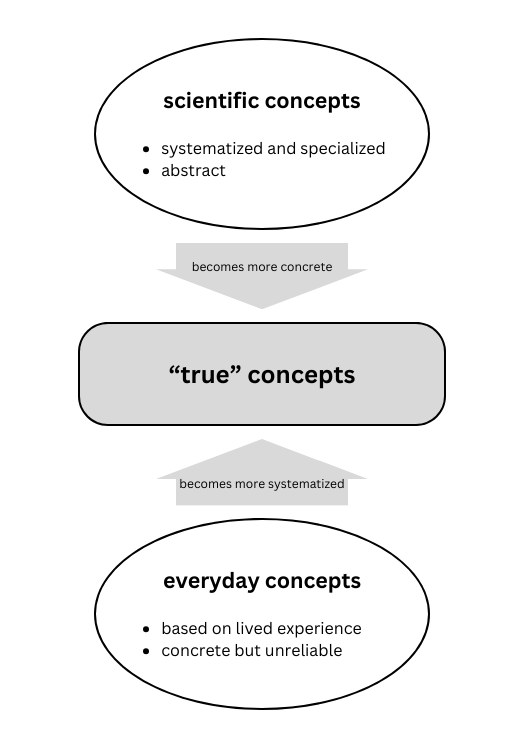

The development of higher mental processes in humans, according to Vygotsky (1978), is mediated by psychological tools, including language, signs, and concepts. Vygotsky claims that adults should teach these psychological tools to children through a process of mediation in which children gradually attain familiarity and, eventually, mastery of them. During this process, scaffolding is first provided and then progressively removed to facilitate the child’s gradual internalization of a given psychological tool (Karpov, 2018). One such psychological tool that allows a child to move beyond everyday concepts – learning based upon personal experience or common activities – is that of scientific concepts. While everyday concepts are born from the concrete interactions in our daily lives and, therefore, often inaccurate or incomplete within other contexts, scientific concepts are systemized and generalizable forms of knowledge that allow us to “transcend our everyday knowledge” (Johnson & Golombek, 2016, p. 5). Through scientific concepts, we are able to construct systemized understandings of the world that we may then consciously reflect upon and manipulate (Moll, 2014). This is not to say, however, that scientific concepts should be simply viewed as superior to everyday concepts for human development. Rather, Vygotsky (1986) argues that both everyday and scientific concepts are required for internalization and self-regulation to occur. Although transferability and accuracy limit the utility of everyday concepts, without them scientific knowledge loses its meaning and significance. Scientific concepts taught directly through formal schooling with no attempt made to highlight the connections with the everyday becomes “inert knowledge” (Whitehead, 1959, p. 193) or “empty verbalism” (Vygotsky, 1986, p. 150). Instead, Vygotsky argues that both everyday and scientific concepts are mutually reinforcing, stating “[w]e believe that the two processes–the development of spontaneous [everyday] and of non-spontaneous [scientific] concepts–are related and constantly influence each other. They are parts of a single process” (1986, p. 157). To facilitate higher mental development and the development of true concepts (Vygotsky, 1986), everyday and scientific concepts are reciprocally dependent, with the top-down scientific concepts growing down into the everyday and accumulating meaning and personal relevance, whereas the “messiness” of the grassroots everyday concepts become controllable and malleable thanks to the heightened consciousness and reflection afforded by scientific instruction (see Figure 1). As Vygotsky notes:

In working its slow way upward, an everyday concept clears a path for the scientific concept and its downward development. It creates a series of structures necessary for the evolution of a concept’s more primitive, elementary aspects, which give it body and vitality. Scientific concepts, in turn, supply structures for the upward development of . . . [everyday] concepts toward consciousness and deliberate use. Scientific concepts grow downward through [everyday] concepts; spontaneous concepts grow upward through scientific concepts. (Vygotsky, 1986, p. 194)

Figure 1

The Reciprocality of Scientific and Everyday Concepts (based on Vygotsky, 1986)

Within education, the Systemic Theoretical Instruction model created by P. Y. Gal’perin (1992) represents a viable approach to the instruction of scientific concepts in line with fundamental theoretical principles of Sociocultural Theory (SCT) (Lantolf, 2024; Lantolf & Poehner, 2014). Gal’perin’s model has since been modified to better meet the needs of language education and is now commonly known as the Concept-based Language Instruction (CBL-I) approach (Table 2).

Table 2

CBL-I Process (Lantolf, 2024, p. 293)

A key feature of this approach is its grounding in Vygotsky’s concept of obuchenie–“teaching/learning as collaborative interactions governed by a mutuality of purpose” (Vygotsky, 1987, p. 212, cited in Johnson & Golombek, 2016)–in that concept-based learning is presented as a dialectical process involving both teacher and learner. As opposed to the situation in much formal schooling, approaches involving obuchenie, therefore, do not consider instruction to be simply delivering knowledge from expert to novice, but rather involving “a double-sided process of teaching/learning, a mutual transformation of teacher and student” (Moll, 1990, p. 24).

Although the potential value of everyday/scientific concept integration has been demonstrated in the studies above, these have focused solely on classroom-based learning featuring a traditional teacher-student dynamic. While this could most certainly be argued to have broad applicability to a wide range of global educational contexts, it also neglects recognition of the substantial role of out-of-class learning (Benson & Reinders, 2011) in language acquisition. Consequently, more research conducted in settings beyond the classroom, such as SALCs, is necessary in order to gain a more well-rounded picture of learning across a language learning landscape of practice (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2015) that includes numerous learning environments.

Student Leadership in SALC Social Learning Spaces

Self-access learning centers (SALCs) have existed in various forms around the globe since the 1970s and active movements for the promotion of self-access learning have emerged in various European countries, Japan, Mexico, Hong Kong, and New Zealand (Thornton, 2021). In their early days, SALCs were viewed as repositories for educational materials where students could study independently. However, due to technological advances and growing recognition of the importance of social factors in second language acquisition and learner autonomy, many modern SALCs have moved away from the provision of physical materials to acting as “person-centered learning environment[s] that actively promote[s] learner autonomy both within and outside the space” (Mynard, 2016, p. 9). Reflective of this social shift in SALCs is the increased presence of informal spaces where students can come and interact in their target language (Kushida, 2020; Murray & Fujishima, 2016). Numerous studies (Balçıkanlı, 2018; Hooper, 2020a; Kurokawa et al., 2013; Murray et al., 2014) have illustrated how these spaces can provide students with valuable opportunities for productive language practice and facilitate the building of social connections with peers within a CoP (Wenger, 1998).

Despite the developmental affordances that they offer, it has been reported that, when attempting to engage in social learning in SALCs, psychological barriers may exist, such as language anxiety, insufficient “ways in” to pre-formed social groups, and problems transitioning between starkly different educational ideologies that affect their accessibility and broad appeal. (Hooper, 2023b, Murray & Fujishima, 2016; Mynard et al., 2020a). Numerous suggestions have been made in terms of how social learning in SALCs can be made more accessible to a broader range of students. These include providing opportunities for multiple levels of engagement in SALCs, enhancing collaboration between SALC staff and users, and helping students to establish their own interest-based learning communities, the setting for this study (Mynard et al., 2020b).

Student leadership has also been shown to be a potentially beneficial contribution to improving SALC accessibility. Lyon (2020) reported how Kokon, a social learning space user, took on an informal leadership role by actively encouraging other students walking by to join group conversations and helped to scaffold their participation. Student leadership and, more specifically, student leadership training within student-led learning communities has also been reported within a handful of studies to have a considerable impact on the ability of a community to meet the needs of both its members and SALC users more broadly (Sigala Villa et al., 2019; Watkins, 2021). Sigala Villa et al. (2019) utilized Knowledge Management (KM) and reflective practice to develop and reflect upon their leadership practices of six student leaders of a conversation club at the Jesuit University of Guadalajara in Mexico. In this study, an intentional CoP was formed by the SALC for the six conversation club leaders who were encouraged to engage in reflective discussions about their experiences as leaders while also considering ideas for future good practices and areas for improvement. Stemming from their engagement in this CoP, the leaders were able to develop coherent management/facilitation guidelines for themselves and future generations of leaders. Moreover, they could reach new understandings of their leadership roles from the social mediation that collaborative group reflection afforded. The issue of accessibility was addressed in the discussions with the leaders identifying the need for a sense of belongingness as a key focal point of their role. As one leader stated, “[s]omething that I have also noticed, [new members] really feel much better when they are called by their names, they don’t need to say my name is… they feel better, welcomed” (Sigala Villa et al., 2019, p. 174). This leadership intervention featured in this study was based primarily on student experience rather than attempting to integrate this everyday knowledge with formal scientific concepts. However, the group’s use of a reflective practice cycle and its grounding in the principles of CoP and KM arguably represents a partly academic framing of student leaders’ everyday funds of knowledge (Moll et al., 1992). In the current study, I built on this existing research into learning community leadership training and examined how everyday and scientific concepts were integrated within one SALC learning community and its leadership practices.

Methods

Setting and Context

The original ethnographic case study on which the current study is based (Hooper, 2023a) was conducted within a small private university located in central Japan. The university has a strong international orientation, with most classes focused on language learning. The more specific setting was the university’s SALC, a facility aiming to develop learner autonomy among its users and help them to self-regulate and reflect upon their own learning. To this end, the SALC features a team of trained learning advisors providing voluntary language advising sessions for students and includes a wide range of physical resources such as DVDs, graded readers, and social resources like workshops. Learner advising is viewed as an important element in the SALC and is based on the notion of intentional reflective dialogue (IRD). IRD is grounded in sociocultural theory and features “a learning advisor promot[ing] deep reflective processes and mediat[ing] learning through the use of dialogue and other tools” (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 1).

The LG and Participants

The specific focus of the current study is the LG, a student-led learning community established in the SALC in 2017. This community was formed, in part, to serve the needs of students lacking the confidence to participate in other learning spaces in the SALC due to perceived barriers to accessibility such as social pressure and strict “English-only” language policies. From its inception, therefore, the LG featured a bilingual language policy in which members could switch freely between Japanese and English to enhance their confidence while practicing their English conversation skills. These accessibility-focused elements of the LG CoP are clearly illustrated in the community’s promotional material published in the SALC’s official newsletter.

Why don’t you improve your English speaking in the LG? You can speak in both Japanese and English, so if you aren’t great at speaking it’s a place you can have fun while learning! Please feel free to visit! (emphasis in original) (LG blurb from SALC newsletter (translated from Japanese), SALC Newsletter, 2019)

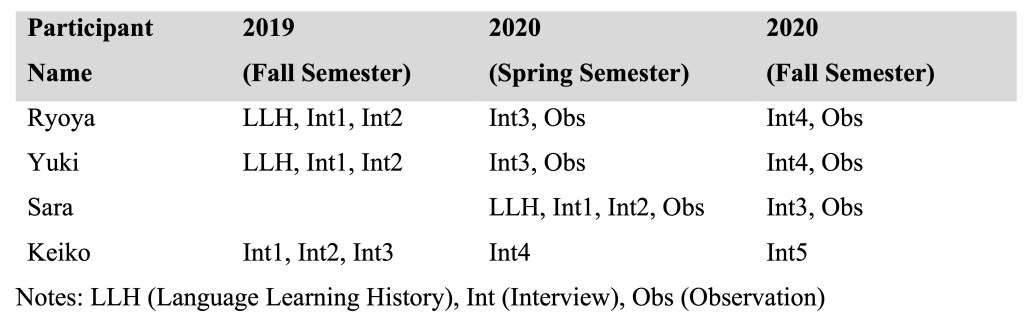

The student participants in the current study (Ryoya, Sara, and Yuki) were three leaders of the LG for a two year period from 2019 to 2021. To gain a more well-rounded perspective of the LG from both an emic and institutional perspective, Keiko, a SALC faculty member and learning advisor was also asked to participate in the study (see Table 3 for full list of participants). All participants were provided a plain language statement outlining the focus and aims of the study and provided informed consent in line with guidelines from my institution’s ethics board. In order to maintain confidentiality, all participants’ names are pseudonyms.

Table 3

List of Study Participants

Data Collection

The gathering of multiple data sources is a fundamental aspect of case study research, enhancing the overall credibility of the findings through the ability to triangulate data (Creswell & Miller, 2000). For the current study, I drew upon four distinct data sources: (1) observational data from the LG (Obs), (2) semi-structured interviews (conducted both in person and online) (Int), (3) language learning histories (LLH) of the three LG leaders, and (4) artifacts collected in the field. A timeline of the key events relevant to the current study is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Study Timeline

The initial phase of data collection took place in the autumn of 2019. This consisted of semi-structured interviews, artifact collection, and oral LLH based on a template utilized by Murphey and Carpenter (2008) (see Appendix A) designed to gain insight into participants’ historical learning trajectories across multiple educational settings. In the case of semi-structured interviews and language learning histories, participants were instructed to respond in whichever language they felt most comfortable (English or Japanese). All Japanese data was subsequently translated into English with the assistance of a native speaker of Japanese fluent in English. It was later determined that the interviews, artifact collection, and LLH alone would be insufficient to gain the desired amount of detail on the LG’s CoP and, accordingly, from spring 2020, participant observation of LG sessions was conducted over one academic year. Furthermore, the artifact collection portion of the study was enhanced as I was given access to instructional materials from the SALC Leadership Course administered by Keiko that Ryoya, Sara, and Yuki joined in April 2020. Details of the data collection process are included in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4

Ethnographic Data Sources

Notes: LLH (Language Learning History), Int (Interview), Obs (Observation)

Table 5

Artifact Collection

Data Analysis

For this study, I adopted an abductive or hybrid approach to data analysis (Proudfoot, 2022; Tavory & Timmermans, 2014) that combines inductive and deductive approaches to the coding of data. This approach recognizes the reality that just as true induction–a state of tabula rasa where all pre-conceptions and existing theoretical knowledge are completely erased–is practically impossible, solely adhering to one’s “favorite theory” (Burawoy, 1998, cited in Tavory & Timmermans, 2014) through deductive coding and deemphasizing any anomalous phenomena is also fundamentally problematic. Therefore, in the current study I chose to utilize a hybrid form of reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; 2020) that combined both deductive and inductive codes. In more concrete terms, Braun and Clarke’s (2006) process for thematic analysis incorporates the following stages through which themes may be created: 1) familiarization with data; 2) generation of initial codes; 3) searching for themes; 4) reviewing themes; 5) defining themes; and 6) final analysis. For instance, participants would frequently discuss negative experiences that they had related to attempting and failing to participate in different social learning spaces within the SALC. I identified this as a recurring pattern in my data and, upon discussion with other researchers in the field and examination of similar phenomena in existing studies, this theme was eventually defined as social learning space inaccessibility. Deductive codes were informed by CoP theory’s elements of domain, community, and practice, and sociocultural theory’s notion of scientific and everyday concepts.

In the case of hybrid reflexive thematic analysis, coding both inductively and deductively was an “iterative and reflexive process” (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006, p. 83, cited in Proudfoot, 2022), in which I moved back and forth between data and existing literature until warranted assertions supported by both participants’ experiences and theory could be formed.

Findings: Leadership Concepts in the LG: Everyday, Scientific, and Integration

In the following section, I will provide examples of the ways in which 1) everyday concepts, and 2) scientific concepts combined to impact the leadership practices within the LG CoP. The LG leaders’ accounts reveal how, through their personal ontogenies and their experiences in the SALC Leadership course, both everyday and scientific concepts appeared to be mutually reinforcing and may have contributed to the formation of true concepts.

Everyday Concepts Through Lived Experience

According to participants, in the earlier generations of the LG, leadership appeared to have been expressed in a caring but initially top-down fashion. Kei, one of the community’s founders, focused on establishing a clear domain for the LG–bilingual and accessible conversation practice for students with lower proficiency or confidence–and controlled almost every facet of LG sessions. Sara recalled how “before when Kei was leader, around him, us active members were there, but maybe only Ryoya, me, or Yuki helped him out a little.” (Sara, Int1, June 23rd 2020), thus highlighting how decision making was essentially limited to the LG’s inner-circle. Ryoya, Yuki, and Sara, as the next generation of leaders, were initially strongly influenced by Kei’s leadership style and tried to imitate it in the early stages of their leadership.

I think Kei is [a] really nice person to welcome new participants. So if some new students come to the LG, he always actively talk[ed] with the recent participants and they exchanged [social media] accounts. So I think thanks to Kei, I can remove my nervous feeling. (Ryoya, Int2, January 14, 2020)

However, as they became more accustomed to their leadership roles, Ryoya, Yuki, and Sara began to frame their notions of effective leadership based on additional sources of everyday knowledge that emerged from their ontogenies and historical multimembership in various CoPs including school clubs, volunteer groups, and part time jobs. In this excerpt, Sara discusses how her experiences in a volunteer group shaped her everyday knowledge relating to group dynamics and how to facilitate a sense of belonging among new community members.

S: Yeah so when I was freshman, I just came into the [volunteer] circle. I was a member of that circle but I was a beginner of the circle so I had a feeling of being a newbie. In summer vacation in my first year I went to Thailand [to] volunteer and…with [the circle] in spring and summer break we went overseas to do volunteer work helping to build houses. So then naturally the members become more central within the group. Then we did a presentation about our experiences of volunteer work and that also naturally helped me to meet more people. Yeah, I had many opportunities to talk [to] people who are in [the circle]… so if I didn’t go to Thailand [in] summer vacation, maybe I [would have] quit the circle.

D: You had a chance to actively participate in community activities.

S: Actively. Yeah. The more actively I participate, the more I want[ed] to join. I wanted to go more, yeah. (Sara, Int2, July 16, 2020)

This type of experience from other CoPs (SALC/PR committees, volunteer groups) that they had historically participated in, led all three of the LC leaders to focus on providing additional opportunities for LG members to actively contribute to each session. Consequently, the leaders introduced chances for members to share and explain notable vocabulary or grammar points, offer ideas for future conversation topics, and give feedback on problems occurring in the community and possible changes that might be made, via a weekly online survey.

Integrating Scientific Concepts Through Leadership Training

Up to this point, the LG leaders’ leadership practices were wholly based on personal experiences and intuition rather than true concepts integrating scientific knowledge. This was to change with Ryoya, Yuki, and Sara enrolling in a credit-bearing English-medium autonomy-supportive leadership course organized by the SALC in spring 2020. The leadership course was designed and administered by Keiko, who was working as a learning advisor and demonstrated a belief in autonomy-supportive teaching and was engaged in advocacy for the student-led learning communities. These influences meant that Keiko designed her course to apply scientific theories and concepts to help students reflect on their lived experiences as community leaders rather than prescribing given leadership practices in a top-down fashion.

Oh, so what I’m trying to do is [getting] the [community] leaders to do my job (as an advisor), like mak[ing] sure that they’re giving themselves opportunity to reflect or helping others to reflect. (Keiko, Int2, November 29, 2019)

The course also featured frequent advising sessions in which students could engage in

IRD (Kato & Mynard, 2016) with Keiko about their vision for their community and ways in which they could operationalize that vision (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Advising Element of the Leadership Course (Leadership Course Materials, Spring 2020)

Through these advising sessions, Keiko used IRD to engage students in reflective dialogue through which she could help learners to broaden their conceptualization of what effective leadership entailed.

A lot of times, the first time when I’m helping leader[s], what’s common is that they say, “I don’t know how to be a team leader. I don’t know how to teach. I don’t know how to lead.” And then I basically go through advising and how it’s okay not to lead people, not to know the answer or not even [teach] people. I guess that’s the advising training or autonomy training. (Keiko, Int3, January 10, 2020)

Within the leadership course, the LG leaders were introduced to numerous scientific concepts derived from research into communities of practice (Wenger et al., 2002), self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017), autonomy-supportive teaching (Reeve, 2016), leadership styles (Lewin et al., 1939), and learner advising (Kato & Mynard, 2016). These concepts were utilized as reflective tools that encouraged student community leaders to analyze the practices of their CoPs through scientific lenses and develop a deeper and more systematic understanding of existing phenomena they experienced in the everyday. To this end, symbolic tools in the form of diagrams, academic terminology, checklists, and flowcharts were combined with social tools such as IRD with Keiko and other peers from different learning communities were core elements of the course. Figure 4 is an example of the course materials focusing on analyzing levels of participation and community structure adapted from the CoP literature.

Figure 4

CoP Structure and Levels of Participation Activity (Leadership Course Materials, Spring 2020)

In the leadership course content and through the various symbolic and social tools it utilized, most elements of the CBL-I process were identifiable including pre-understanding, concept presentation, communicative and dialogic verbalization, and performance (Table 6).

Table 6

CBL-I Elements in the Leadership Course (adapted from Lantolf, 2024)

Through this type of concept-based approach to leadership training, Ryoya, Yuki, and Sara appeared to have been able to analyze their everyday experiences within their learning communities through different scientific lenses. There were indications that this process may have contributed to a deeper understanding of the theories they were exposed to as they were framed in the relevance of the everyday while also fostering a deeper understanding of their everyday experience in the LG up to that point. Bringing learners’ experiences into the course and using academic theories acting as “gates through which awareness penetrates the realm of [everyday] concepts” (Vygotsky et al., 1944/2001, p. 68) could conceivably have led to a dialectical obuchenie promoting the internalization of course content. In terms of internalization, scientific concepts contributed to the LG CoP’s practice by creating new approaches to address recurring or unresolved community issues. Below is an example of how awareness of Basic Psychological Needs theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017) impacted the way in which Ryoya addressed an ongoing issue of finding new conversation topics for LG meetings.

D: So, um, I remembered like when we first spoke in 2019, you said one of the biggest challenges for you guys is thinking up [conversation] topics.

R: Mm.

D: So now the members are doing it for you.

R: Yeah, yeah. (laughs).

D: What do you think about that?

R: Yeah, it’s really nice and convenient for us. And also it leads to increasing participants’ relatedness or competence.

D: Wow. Self-determination theory.

R: Yeah. (laughs)

D: Did this come partly from the leadership course?

R: Yes, of course.

(Ryoya, Int4, November 12, 2020)

In one interview, Sara described how discussions on the scientific concepts relating to leadership styles had allowed her to analyze past community leaders like Kei and therefore gain new perspectives on her present status and identity as an LG leader. This may have further encouraged the LG leaders to progress beyond viewing effective leadership as a monolithic concept as they had in their previous attempts to imitate Kei’s leadership style. In the following excerpt, Ryoya describes how his perspective on LG leaders’ roles in the community evolved based on what he had learned in the Leadership Course.

Before I took the leadership course I felt like the community should be led by leaders only and the participants are just participants. So they always just join the community and listen to the leader’s speech and just do activities. But thanks to the leadership course, I could change my mind that the community is for all of us, like all of the participants and leaders. So we need to improve the community [through] all of us, by ourselves. So yeah, that changed my mind. (Ryoya, Int4, November 12, 2020)

Moreover, Sara’s deeper perceived understanding of leadership styles (Lewin et al., 1939) contributed to her developing her own sense of self-belief and plausibility (Prabhu, 1990) in terms of how the community had evolved through her leadership.

So when I remembered people who were group leaders before, they all had different styles of organiz[ation]. I just realized that because Kei was this style, the LG was like that then… I just analyzed various things and thought about why the LG is like it is now. Ryoya, Yuki and me, the three of us, we’re all different but even though we’re not like traditional leaders, we’re making this style of LG. I’m doing my best in this way, so this is okay I think. (Sara, Int3, December 15, 2020)

Sara’s response illustrates how scientific concepts may have helped to “restructure and raise [everyday] concepts to a higher level” (Vygotsky, 1987, p. 220, cited in Brooks et al., 2010) as the theories learned in the leadership course appeared to have helped her to revisit her past and present experiences with new eyes and partly contributed new discoveries.

Discussion and Conclusions

The question underpinning the current study concerned how the LG’s leadership practices integrated everyday and scientific concepts. Following their experiences in the SALC leadership course, the ethnographic data illustrates numerous ways in which the leaders had, at least partly, internalized various academic concepts that influenced not only their individual learning trajectories, but also the path of the LG.

Furthermore, the three LG leaders’ experiences in the leadership course were arguably congruent in many ways with the concept-based instructional approaches advocated by Lantolf (2024) and Lantolf and Poehner (2014) where explicit instruction in scientific concepts is internalized through dialogic and communicative verbalization and through finding avenues to apply them to everyday practice. Within the leadership course, students’ lived experiences of leadership and community membership appeared to be given equal weight to the academic theories introduced in the course and the course materials highlighted numerous occasions where the everyday and the scientific were dialectically analyzed. This meant that for Ryoya, Yuki, and Sara, the scientific felt less detached and the everyday took on new dimensions to be explored and molded. Furthermore, in Sara’s case, we also observe how scientific concepts came to reorient her perspectives on both the past and the present as she saw her historical learning experiences (everyday knowledge) through new eyes and was able to form new interpretations of them. Through the leadership course, Sara was afforded the ability to merge the everyday and scientific to create true concepts that allowed her to reconceptualize what she thought she knew about leadership and construct new possibilities for the future (Johnson & Golombek, 2016).

Another way in which integration of concepts occurred was through the obuchenie that was fostered through a collaborative and dialogic approach to learning the course content. Utilizing an autonomy-supportive approach influenced by her role as a learning advisor, Keiko appeared to have guided learners both directly and indirectly by providing symbolic tools and opportunities for expert/novice and peer communicative verbalization. Although Keiko’s direct and indirect instruction on each academic theory the LG leaders encountered may have scaffolded their basic understanding, in order for this to move beyond the mere reproduction of “inert knowledge” (Whitehead, 1959, p. 193), more was necessary. Through an instructional approach partially analogous with CBL-I, frequent opportunities to engage in IRD, and a requirement to apply what they had learned in the LG’s practice, these academic theories seemed to have evolved from “isolated, ossified, and changeless formation[s]” to “an active part of the intellectual process, constantly engaged in serving communication, understanding, and problem solving” (Vygotsky, 1986, p. 105). The students’ active engagement and negotiation in this process was essential as they were required to take the concepts examined in the course into the everyday and experiment with how they could be applied in their communities. Some examples of this experimentation include the leaders frequently restating the LG’s CoP’s domain, providing opportunities for peripheral engagement (Wenger et al., 2002), exhibiting democratic leadership by actively soliciting feedback (Lewin et al., 1939), and attempting to enhance belongingness and relatedness for new members (Ryan & Deci, 2017). A dialectical teacher/student relationship was fostered as students’ findings were brought to the following class where they could be collaboratively analyzed through IRD in advising sessions. One key principle of IRD within learner advising is that dialogue is, as much as possible, controlled by the learner rather than the advisor (Kato & Mynard, 2016). Consequently, although complete equality may be realistically impossible due to an existing power gap between advisor and student, learner advising affords opportunities for greater symmetry–“equal distribution of right and duties in talk” (van Lier, 1996, p. 175) –in learner interactions. The intersectional symmetry that formed the basis of the advising sessions meant that they were arguably congruent with the “collaborative interactions governed by a mutuality of purpose” (Vygotsky, 1987, p. 212, cited in Johnson & Golombek, 2016) that Vygotsky envisioned when describing obuchenie. As Keiko herself not only taught about autonomy support, but also taught with autonomy support (Daniels, 2001), she facilitated imitation and ultimately internalization as course concepts became both “the tool and result” (Swain et al., 2015, p. 57 emphasis original). In addition, it can be assumed the reflections and insights that the student leaders brought back with them also developed Keiko’s understanding of the course material through elucidating the connections between the theories she taught and how they were applied in the LG.

Due to the highly focused and specific nature of the ethnographic research that formed the basis for this study, there are clear limitations to the generalizability of its findings for both researchers and practitioners. Furthermore, future studies in this area should incorporate more participant observation or micro-level conversational analysis of instructional sessions so as not to solely rely on secondary perspectives on how the leadership course was conducted. These limitations aside, the leadership course featured in this study arguably represents an innovative new facet of social learning within self-access that highlights how the skills of learning advisors may be effectively applied to other areas within SALCs, such as CBL-I-type instruction and community support. Consequently, these potentially exciting new avenues for self-access evolution warrant increased attention within SALC research in the years to come.

Notes on the Contributor

Daniel Hooper is an associate professor in the Department of English Communication at Tokyo Kasei University. He has been teaching in Japan for 18 years in a variety of contexts including primary/secondary schools, English conversation schools, and universities. His research interests include teacher and learner identity, reflective practice, self-access learning communities, and communities of practice.

References

Balçıkanlı, C. (2018). The “English Café”. In G. Murray, & T. Lamb (Eds.), Space, place and autonomy in language learning (pp. 61–75). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781317220909-5

Benson, P. (2017). Language learning beyond the classroom: Access all areas. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.37237/080206

Benson, P., & Reinders, H. (Eds.) (2011). Beyond the language classroom. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230306790

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2). 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Brooks, L., Swain, M., Lakpin, S., & Knouzi, I. (2010). Mediating between scientific and spontaneous concepts through languaging. Language Awareness, 19(2), 89–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410903440755

Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Into Practice, 39(3), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

Daniels, H. (2001). Vygotsky and pedagogy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203469576

Gal’perin, P. Y. (1992). Stage-by-stage formation as a method of psychological investigation. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 30(4), 60–80. https://doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-0405300460

Hooper, D. (2020a). Understanding communities of practice in a social language learning space. In J. Mynard, M. Burke, D. Hooper, B. Kushida, P. Lyon, R. Sampson, & P. Taw (Eds.), Dynamics of a social language learning community: Beliefs, membership, and identity (pp. 108–124). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/MYNARD8908

Hooper, D. (2020b). Modes of identification within a language learner-led community of practice. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 11(4), 301–327. https://doi.org/10.37237/110402

Hooper, D. (2023a). Exploring and supporting self-access language learning communities of practice: Developmental spaces in the liminal [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Nagoya University of Foreign Studies. https://nufs-nuas.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/1814/files/(O7)Hooper_%E5%8D%9A%E5%A3%AB%E8%AB%96%E6%96%87%E5%85%A8%E6%96%87.pdf

Hooper, D. (2023b). Mind the gap: Student-developed resources for mediating transitions into self-access learning. JASAL Journal, 4(1), 32–54. https://jasalorg.com/mind-the-gap-student-developed-resources-for-mediating-transitions-into-self-access-learning/

Johnson, K. E., & Golombek, P. R. (2016). Mindful L2 teacher education: A sociocultural perspective on cultivating teachers’ professional development. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315641447

Karpov, Y. V. (2018). Acquisition of scientific concepts as the content of school instruction. In J. P. Lantolf, M. E. Poehner, and M. Swain (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of sociocultural theory and second language development (pp. 102–116). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315624747-7

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall. https://www.pearson.com/en-us/subject-catalog/p/experiential-learning-experience-as-the-source-of-learning-and-development/P200000000384/9780133892505

Kurokawa, I., Yoshida, T., Lewis, C. H., Igarashi, R., & Kuradate, K. (2013). The Plurilingual Lounge: Creating new worldviews through social interaction. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2012.04.014

Kushida, B. (2020). Social learning spaces. In J. Mynard, M. Burke, D. Hooper, B. Kushida, P. Lyon, R. Sampson, & P. Taw (Eds.), Dynamics of a social language learning community: Beliefs, membership, and identity (pp. 12–28). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/MYNARD8908

Lantolf, J. P. (2011). The sociocultural approach to second language acquisition: Sociocultural theory, second language acquisition, and artificial L2 development. In D. Atkinson (Ed.), Alternative approaches to second language acquisition (pp. 24–47). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203830932-2/sociocultural-approach-second-language-acquisition-james-lantolf

Lantolf, J. P. (2024). On the value of explicit instruction: The view from sociocultural theory. Language Teaching Research Quarterly, 39, 281–304. https://doi.org/10.32038/ltrq.2024.39.18

Lantolf, J. P., & Poehner, M. E. (2014). Sociocultural Theory and the pedagogical imperative in L2 education: Vygotskian praxis and the research/practice divide. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203813850

Lewin, K., Lippitt, R, and White, R. K. (1939). Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally created ‘social climate’. Journal of Psychology, 10, 271–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1939.9713366

Lyon, P. (2020). ‘If some freshman come to us, I said like, “Please join us”’: Kokon’s Story. In J. Mynard, M. Burke, D. Hooper, B. Kushida, P. Lyon, R. Sampson, & P. Taw (Eds.), Dynamics of a social language learning community: Beliefs, membership, and identity (pp. 51–57). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788928915-008

Moll, L. C. (1990). Introduction. In L. C. Moll (Ed.), Vygotsky and education: Instructional implications and applications of sociohistorical psychology (pp. 1–27). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139173674.002

Moll, L. C. (2014). L. S. Vygotsky and education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203156773

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31(2), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849209543534

Murphey, T., & Carpenter, C. (2008). The seeds of agency in language learning histories. In P. Kalaja, V. Menezes, & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Narratives of learning and teaching EFL (pp. 17–35). Palgrave Macmillan. https://link.springer.com/book/9780230545434

Murray, G., Fujishima, N., & Uzuka. M. (2014). Semiotics of place: Autonomy and space. In G. Murray (Ed.), Social dimensions of autonomy in language learning (pp. 81–99). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137290243_5

Murray, G., & Fujishima, N. (2016). Social spaces for language learning: Stories from the L-café. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-53010-3

Mynard, J. (2016, June 25). Taking stock and moving forward: Future recommendations for the field of self-access learning [Plenary session]. 4th International Conference on Self-Access, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico. https://www.academia.edu/28165120/Taking_Stock_and_Moving_Forward_Future_Recommendations_for_the_Field_of_Self_access_Language_Learning

Mynard, J. (2019). Advising and self-access learning: Promoting language learner autonomy beyond the classroom. In H. Reinders, S. Ryan, & S. Nakamura (Eds.), Innovations in language learning and teaching: The case of Japan (pp. 185–209). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12567-7_10

Mynard, J., Burke, M., Hooper, D., Kushida, B., Lyon, P., Sampson, R., & Taw, P. (2020a). Dynamics of a social language learning community: Beliefs, membership, and identity. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/MYNARD8908

Mynard, J., Lyon, P., Taw, P., & Hooper, D. (2020b). Implications and practical interventions. In J. Mynard, M. Burke, D. Hooper, B. Kushida, P. Lyon, R. Sampson, & P. Taw (Eds.), Dynamics of a social language learning community: Beliefs, membership and identity (pp. 166–175). Multilingual Matters. http://doi.org/10.21832/MYNARD8908

Prabhu, N. S. (1990). There is no best method – Why? TESOL Quarterly, 24(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586897

Proudfoot, K. (2023). Inductive/Deductive hybrid thematic analysis in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 17(3), 308–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/15586898221126816

Reeve, J. (2016). Autonomy-supportive teaching: What it is, how to do it. In W. C. Liu, J. C. Wang, & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Building autonomous learners (pp. 129–152). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-630-0_7

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford. https://doi.org/10.1521/978.14625/28806

Saldaña, J. B. (2017). Mediating role of leadership in the development of communities of practice. In J. McDonald, & A. Cater-Steel (Eds.), Communities of practice: Facilitating social learning in higher education (pp. 281–312). Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-2879-3_13

Saxe, G.B., De Kirby, K., Kang, B., Le, M., & Schneider, A. (2015). Studying cognition through time in a classroom community: The interplay between “everyday” and “scientific concepts.” Human Development, 58(1), 5–44. http://doi.org/10.1159/000371560

Sigala Villa, P., Ruiz-Guerrero, A., & Zurutuza Roaro, L. M. (2019). Improving the praxis of conversation club leaders in a community of practice: A case study in a self-access centre. Studies in Self-Access Learning, 10(2), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.37237/100204

Swain, M., Kinnear, P., & Steinman, L. (2015). Sociocultural theory in second language education: An introduction through narratives (2nd Ed.) Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783093182

Tavory, I., & Timmermans, S. (2014). Abductive analysis: Theorizing qualitative research. The University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226180458.001.0001

Thornton, K. (2021). The changing role of self-access in fostering learner autonomy. In M. J. Raya, & F. Viera (Eds.), Autonomy in language education: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 157–174). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429261336-13

Van Lier, L. (1996). Interaction in the language curriculum: Awareness, autonomy, and authenticity. Longman. https://www.routledge.com/Interaction-in-the-Language-Curriculum-Awareness-Autonomy-and-Authenticity/Lier/p/book/9780582248793

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674576292

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language, translated and edited by A. Kozulin. MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262720014/thought-and-language/

Vygotsky, L. S., Luria, A., & Leontiev, A. N. (2001). Linguagem, desenvolvimento e aprendizagem [Language, development and learning]. Ícone Editora. (Original work published 1944)

Watkins, S. (2021). Becoming autonomous and autonomy-supportive of others: Student community leaders’ reflective learning experiences in a leadership training course. JASAL Journal, 2(1), 4–25. https://jasalorg.files.wordpress.com/2021/07/3-autonomy-supportive-training-for-student-leaders-final2.pdf

Watkins, S. (2022). Creating social language learning opportunities outside the classroom: A narrative analysis of learners’ experiences in interest-based learning communities. In J. Mynard & S. Shelton-Strong (Eds.), Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom: A self-determination theory perspective (pp. 182–214). Multilingual Matters. https://www.multilingual-matters.com/page/detail/Autonomy-Support-Beyond-the-Language-Learning-Classroom/?k=9781788929035

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803932

Wenger, E. (2010). Communities of practice and social learning systems: The career of a concept. In C. Blackmore (Ed.), Social learning systems and communities of practice (pp. 179–198). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84996-133-2_11

Wenger, E., McDermott, R. A., & Snyder, W. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Harvard Business School Press. https://books.google.co.jp/books/about/Cultivating_Communities_of_Practice.html?id=m1xZuNq9RygC&redir_esc=y

Wenger-Trayner, E., Fenton O’Creevy, M., Hutchinson, S., Kubiak, C., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Learning in landscapes of practice: Boundaries, identity and knowledgeability in practice-based learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315777122

Whitehead, A. N. (1959). The aims of education. Daedalus, 88, 192–205. https://books.google.co.jp/books/about/Aims_of_Education.html?id=WbXs-vyWPPgC&redir_esc=y

Appendix A

Language Learning History Guidelines (adapted from Murphey & Carpenter (2008))

My Language Learning History

Talk about your language learning history from when you began learning English to the present. Feel free to write as much as you like. You can speak in English or Japanese (or a mixture).

Some questions you may want to answer in your story (you don’t have to answer all of these questions – some of them may not be relevant):

- Have you ever written your language learning history before?

- When did you start learning English?

- How did you learn English in elementary school, JHS, and HS?

- Did you learn English in eikaiwa schools or in juku?

- What positive and negative experiences did you have and what did you learn from them (in and out of school)?

- What were you expecting before you came to university?

- What were you surprised about in your university classes?

- What were you surprised about in the SAC?

- How have you changed your ways of language learning since coming to the university?

- What are the things that you found especially helpful?

- What are the areas that you still want to improve in?

- How do you think your next three years will be?

- What are your language learning plans and goals after graduation?

- What advice would you give to this year’s first year students?