Diana Feick, School for Cultures, Languages, and Linguistics, The University of Auckland, New Zealand

Mareike Schmidt, School for Cultures, Languages, and Linguistics, The University of Auckland, New Zealand

Feick, D., & Schmidt, M. (2024). Geographical and spatial inclusion in language teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(3), 345–366. https://doi.org/10.37237/150303

Abstract

This article presents a duoethnographic study by two lecturers of German in a B.A. program at Waipapa Taumata Rau – The University of Auckland (UoA) in Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ). With an abrupt change to online teaching in March 2020, we had to redesign our language acquisition courses at different levels. Retrospectively, we conducted a duoethnography to investigate our development of courses that are inclusive for onshore as well as offshore students and lecturers. Our personal experiences across different courses are the main data sources, and include our e-mail exchanges, written narrative reflections, and dialogic oral reflections. They served to interrogate and critically reflect our unique experiences while attempting to foster location-based inclusivity. We used thematic analysis to interpret the data into emerging themes. This analysis provided us with a better understanding of the development of our course designs and the role of spatial and geographical inclusion in these courses. Informed by the collaborative reflection of our experiences, as the main finding, we identified three setups and four variations of these for location-based inclusive course designs. In our reflections we illustrate how these designs provided multiple opportunities for contributing to a place-sensitive teacher and learner autonomy.

Keywords: spatial inclusion, geographical inclusion, teacher autonomy, inclusive course design, duoethnography

Since the Covid-19 pandemic, virtual learning spaces have gained an increased importance. To date, the first studies emerged investigating virtual language learning spaces during that time in institutional settings (e.g., the two special issues of journals for German as a foreign language: InfoDaF 5 by Feick et al. (2021), and GFL 1 by Biebighäuser 2022) as well as in self-access learning (special issue of SiSAL edited by Peña Clavel et al., 2020). These studies typically focus on the importance of learner autonomy in virtual learning spaces, and to a lesser extent on the role of teachers’ autonomy and their agency for designing these spaces. From auto- or duoethnographic studies about emergency online teaching we know that course designers were confronted with often challenging power relationships (Ren, 2022). They experienced themselves as powerful or powerless influenced by institutional, societal or political factors, so that their design agency oscillates between voluntary choices and institutional obligations (Ren, 2022). Jung et al. (2021) reflected on the development of their problem-solving skills during emergency online teaching and their increased awareness for students’ problems and needs which they also consider as beneficial for their post-pandemic online teaching. These experiences might differ in different contexts. Our study focuses on our course design experiences in NZ and the spatial inclusion of our students at different locations.

Starting as emergency remote online teaching at the beginning of the pandemic, universities had to include students in NZ and from overseas into their course offerings. Throughout the pandemic, a transition from emergency remote teaching to online and blended learning occurred. In the second phase of the pandemic our courses had to be readapted as dual delivery for on-campus students and remote domestic and overseas students. Different models for dual delivery for on-campus and online teaching of the same course emerged. Classrooms in this context need to be seen as both physical as well as virtual ones. As a direct result of the pandemic, in 2021, we also were asked to redesign our beginner’s course as a blended-learning course to rationalize our teaching and make our offerings more viable. For any of these arrangements, as we quickly noticed, an even higher language learner autonomy as well as teacher autonomy was required than within the usual on-campus teaching.

Our duoethnography explores the development of our course designs and our experiences with their implementation from a spatial perspective. We first present our teaching context and position ourselves as German lecturers. Then we describe our duoethnographic research methodology, our data collection, and analysis. In the third section, we present and discuss our research findings and finally, draw a conclusion and reflect on further implications of our study.

Our Context and We as Lecturers

We, Diana and Mareike, are lecturers in the German unit at Waipapa Taumata Rau – The University of Auckland (UoA) in Aoteroa New Zealand. This is the biggest of the three programs in German (Studies) in the country. Over the last 15 years, German (Studies) has undergone constant reforms in Australia and NZ to react to the ever-changing educational landscape that increasingly aims to meet neoliberal expectations of economic viability (Lay & Feick, 2024). Nevertheless, these reforms and experiences with past earthquake disasters were also the initiator of implementing digital technologies into language teaching with the expectation of increasing course delivery efficiency and student engagement (ibid.). Against this background, language teaching at NZ universities can be described as relatively progressive with regards to the integration of digital technologies even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the pandemic, NZ had rigorous measures to protect its citizens from the Coronavirus: the borders were closed from March 2020 until full opening in the second half of 2022. Not only NZ citizens and workforce hired abroad, but also all international exchange students and those who were visiting their home countries when the borders closed had to remain outside NZ, as well as international teaching staff not present in the country before the border closure. In our case, about 1/3 of our language German beginner students being international students, mainly from China and other Asian countries, were affected by this closure.

The emergency remote teaching at UoA started in March 2020 with semester 1, when all students, onshore and offshore, were taught online. Over the following months, until August 2022, teaching transitioned back to campus without mandatory student presence and with varying teaching setups implemented by the lecturers. In our language acquisition courses, we decided against asynchronous approaches that provided only slides and lecture recordings, which was the default approach in most non-language-related courses. Instead, we offered live online courses via Zoom, provided additional (online) materials to practice, and worksheets with further explanation of the content. This was informed by our belief that engagement, interaction, and cooperation is less likely to be developed through asynchronous course delivery. Reoccurring lockdowns in Auckland in 2021 made it necessary to adapt quickly; however, teaching online was the status quo until the end of the pandemic in 2022.

The university, on an executive level, had to react to the changing alert levels with dynamic adaptations, challenging both teaching staff and enrolled students. After the borders were fully opened back up in August 2022, we still had to accommodate the learning needs of offshore students whose visa applications were still not processed until semester 1 2023.

In our study we focus on four language acquisition courses at three proficiency levels (German 101, German 200, German 301, German 302/306) and retrospectively carried out a duoethnography to compare our experiences with different approaches and the constant adaptation of course designs and what this meant for the spatial inclusion of lecturers and students.

Duoethnographic studies typically include the self-positioning of the involved researchers to provide a contextual embedding of the individual and dialogic narratives. Therefore, in the following section we will present ourselves, our professional background, and our current areas of work and research.

The Lecturers: Mareike

Having a background of being a teacher for German as a foreign language for 15 years with various positions at universities in Poland, China and now NZ, my professional life is embedded in international contexts. During my engagements in Poland and in China I fulfilled two roles: being employed as a lecturer at a local university to teach in language acquisition courses, but also being a representative of the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) that includes representing German higher education, consulting about funding schemes, and encouraging international exchange.

During the pandemic, I had already gained significant experience in teaching online: I was employed by a university in Beijing from September 2019 and was a lecturer in their German program. With the start of the pandemic, I left the country and conducted all courses online and synchronously. This was my first extensive online-teaching experience over a long term. I started my position at UoA in NZ remotely in February 2021, having been kept in the loop about teaching and learning adaptations from December 2020, due to closed borders. Coming from an ad hoc context of having to orient myself in tools and teaching resources, it was a relief having all of the necessary software and support offered by UoA.

A crucial point of my teaching is to keep students motivated and engaged – not only with the content of the course, but also with each other and their (during the pandemic limited) social environment. Furthermore, to enable them to autonomously engage with course content and beyond is of my interest. I am implementing media technologies, virtual exchanges with learners of German from different countries and cultures, and project-oriented coursework such as the creation of podcast series and vlogs into my teaching to foster engagement, create awareness for the benefits of language learning and enable students to learn and use language autonomously in outside-class settings.

The Lecturers: Diana

My background is in teaching German as a foreign and second language and training future language teachers, as well as in professional development of in-service German teachers. Over the last 20 years I have had experiences in different working contexts in Europe as well as in South America before joining the UoA in 2017 as a senior lecturer in German and Applied Linguistics/Language Teaching. Since my undergraduate studies I have always been interested in combining my two major subjects in my future professional life: German as a Foreign Language and Communication and Media Studies. This led to a PhD on group autonomy in a mobile language learning context (Feick, 2016, 2018). Ever since, I have been passionate about exploring the use of digital media in language teaching and research exploring innovative approaches like mobile-assisted language learning (MALL) (Feick, 2020), blended language learning (Feick & Tolosa, forthcoming), virtual language learning spaces (Feick & Rymarczyk, 2022) and virtual exchange (Biebricher et al., 2024, Feick & Knorr, 2021a, 2021b, 2022). Since arriving at UoA my researcher perspective was additionally informed by my own teaching of German in the undergraduate curriculum, and I could explore and implement different media-based teaching approaches that had scientifically proven to be conducive to language learning (overviews in Reinders & Stockwell 2017 or Kukulska-Hulme 2018),

Coming from rather resource-limited teaching environments, at Waipapa Taumata Rau – The University of Auckland in New Zealand I encountered a workplace that is supportive of implementing the latest digital technologies and always provides the necessary resources and curriculum flexibility to advance these initiatives. Educational equity is particularly important for me, so my main aim always has been to incorporate digital tools and resources that do not come with an extra cost for our students and are easily accessible. At the same time, I try to implement digital innovations in my teaching that foster my student’s social learning and communication skills as well as the development of their learner autonomy.

Literature Review: Autonomy and Inclusion From a Spatial Perspective

In our study, we follow the commonly established understanding of learner autonomy in the field of applied linguistics, characterized by the willingness and ability of taking charge over one’s own learning (Benson, 2011). In addition to the focus on the learners, we include the interrelated concepts of teacher autonomy, agency, and (em)power(ment) (La Ganza, 2008, Nicolaides, 2017) into our theoretical framework. With agency we refer to the capacity to act deliberately in order to fulfil personal meaningful purposes, being aware of one’s own actions and of their significance and relevance (Lantolf 2013). This is closely connected to teacher autonomy which Jiménez Raya et al. (2024, p. 2) define as: “a personal construct, involving responsible self- determination, choice, authenticity, rational reflection, and ability to face and surpass constraints”. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the teachers’ ability and possibility to take control over their professional activities and development, and constantly improve and adapt their course design and teaching approaches within a given sociocultural context and other more global circumstances. Furthermore, teacher autonomy helps to foster the development of learner autonomy (Benson, 2008, Jiménez Raya et al., 2024, La Ganza, 2008) and is especially relevant in the study of virtual learning spaces.

Since the expansion of language teaching and learning into the virtual space, which predates but became a necessity during the COVID-19 pandemic, research in autonomous language learning is increasingly focusing on the role of space and place in this context (Benson, 2021, Feick & Rymarczyk, 2022, Murray & Lamb, 2019). This is also referred to as the “spatial turn” (Benson 2021) and includes not only the study of the location of where learning and teaching takes place, but according to our understanding, also includes the study of the mode of delivery (e.g., in person vs. online). Within this discourse, the concept of place is mainly understood as a physical location while the term space is mostly used for virtual learning environments (Feick & Rymarczyk, 2022, p. 10). Furthermore, Benson (2021, p. 7) distinguishes between an areal and an individual perspective of space. On the one hand, the areal perspective is a “geographically demarcated area (e.g., a campus, a city or a region)” which also includes the internet. On the other hand, an individual perspective refers to the “configuration of settings assembled by an individual learner”, which also includes virtual settings. In formal language learning environments, the design of virtual learning spaces is mostly teacher-driven. This includes that institutional language course providers need to ensure that the inclusion of all learners and their participation is not affected by the digital divide in society. Even developed countries like NZ are still affected by limited access to computers, mobile devices or the internet, which is mostly linked to the geographical and socio-economic background of a person.

For the NZ context during the pandemic, inclusion within one course refers to the integration of overseas students in different time zones and at various geographical locations. We call this geographical inclusion. We use the term spatial inclusion when students are at the same geographical location (e.g., a city or a country) but cannot join classes in person for other reasons. In some cases, both aspects of inclusion can overlap. Little is known about the causes, (design) approaches for and teacher perceptions on geographical and spatial inclusion. Therefore, in this study, we aim at answering the following research questions:

- What reasons lead to the geographical and spatial inclusion of students during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2022) in our German language courses?

- How did we constantly adapt our course design to best cater to the different needs of teachers and (increasingly autonomous) learners in physical and virtual learning environments?

- How did we perceive this experience?

Methodology

Duoethnography

Duoethnography, which is also known as collaborative or collective autoethnography (Blalok & Akehi, 2018), is a dialogic research approach and derives from the qualitative methodologies of autoethnography and narrative enquiry. While in classic ethnographic studies, individual researchers investigate a specific phenomenon that is usually outside of their own world of experience, in duoethnography, the focus is on at least two investigators’ subjective experiences, perspectives and reflections, enabling a multi-layered understanding of the phenomenon under investigation (Burleigh & Burm, 2022). With regard to this phenomenon, the researchers construct their experiences narratively through critical self-reflection and develop them further dialogically. In duoethnography, researchers are researchers and those being researched at the same time (Lawrence & Lowe, 2020; Norris & Sawyer, 2012). It can therefore also be understood as a postmodern approach that assumes subjectivity, especially in dialogue and communication, as a necessary part of the method (Lowe & Lawrence, 2020; Sawyer & Norris, 2013).

While increasingly being implemented in foreign language research, duoethnography has also been used to reflect on emergency online teaching experiences during the pandemic (Jung et al. 2021) or to critically study the impact of COVID-19 on online learning experiences from cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary perspectives (Wilson et al., 2020).

Data Collection

Our data collection included three steps. As our first data source, we collated our e-mail correspondence during December 2020, when Mareike joined our team working remotely from Germany, and October 2022 when we concluded our teaching of the second semester during that academic year. The overall word count of this corpus consists of 29,189 words (corpus 1).

The second step of our data collection took place in June 2023 and entailed the creation of one written narrative reflection each based on the individual close reading of our e-mail correspondence included in corpus 1. We wrote these reflections without using specific prompts; rather, we reflected on our experiences and engaged in retrospective meaning-making and contextualization of our course design and course coordination experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. The overall word count of this corpus consists of 4,099 words (corpus 2).

The third step of the data collection consisted of dialogic reflections based on our two narratives which were audio recorded with the recording software Audacity and later transcribed. The overall duration of this corpus is 101 minutes (corpus 3) and its data is represented with the relevant time stamps in this text. In this phase, we reacted to each other’s written narratives, expanded them, explained certain aspects to each other in more detail, and also compared our perceptions of past events. This was also an important part of collaborative meaning-making and jointly reconstructing our experiences as chronologically accurate and detailed as possible. Furthermore, this step also served as the first step of our data analysis since we already engaged in dialogic interpretation of our narratives.

Data Analysis

Treating our three data sets holistically, we first read all texts closely and subsequently reconstructed jointly chronological phases during the period of interest in conjunction with major events that marked these phases, e.g., the beginning and end of lockdowns or the implementation of a new university-wide teaching guideline. After that, we did a thematic analysis and identified three different design setups and four sub-varieties (see findings). In addition, we interpreted our oral and written narratives focusing on our experiences and perceptions and discussed emerging themes such as factors for inclusion and power dynamics.

Findings

In the following section we will present the findings of our three research questions. The first part of our results section answers the first research question about the reasons that led to the geographical and spatial inclusion of students during the COVID-19 pandemic in four courses of our German program. In the second part we answer research question two and three combined since the different forms of adapting the course design and our perception of this experience are closely connected.

Causes for Geographical and Spatial Inclusion

In our data, we noticed that the reasons for inclusion during the lockdowns differ from those after the resuming of teaching on campus; however, attending classes on-campus wasn’t feasible for all students. During the two lockdowns of Auckland, all teaching happened online, so all the students were expected to participate in the remote delivery of courses independently from their geographical location. We can describe this as the inclusion of all students in the same online space, but this required the necessary hardware and stable internet connections and bandwidth. Not all our students could rely on these conditions, so their participation was sometimes disrupted and needed to be compensated with independent self-study of the course contents. Also, for us as teachers, we had to partially upgrade our home internet data rates to be able to execute this approach without disruptions.

At a later stage, once on-campus teaching resumed, we nevertheless offered students the chance to participate online, because different reasons prevented them from joining classes in person. From our e-mail correspondence with students, we learned that some of our students live remotely or out of town, so to avoid the long commute, it was more suitable for them to participate online together with the offshore students. Some of these students also suffered from increased transportation costs and the increased unreliability of public transport in Auckland. We also encountered the theme of health restrictions that prevented students from attending classes in person, or they were required to self-isolate, but our online or hybrid offerings still allowed them to engage in our classes:

I agree with your suggestions: she could sit S2 in 201 (online) and then take a placement test for 301. If she passes, she could enrol in 301[..]. This would affect all the courses she would like to take online with us in the future, as they are not designed as online courses, but the faculty seems to accept students who can only study online. (Diana, email 6/8/21)

Other students also reported they had work obligations, so attending classes online was easier to incorporate into their busy daily schedules. There were also students that had care responsibilities that prevented them from leaving their home, so they also benefited from our online or hybrid course delivery.

This demonstrates that there is a diverse range of personal or socioeconomic circumstances that led to that spatial inclusion through online participation in on-campus classes or online streams through online or hybrid course delivery. Those different course setups as well as our perception of developing and implementing them are described in more detail in the following section.

Inclusive Course Setup and Our Perceptions

The second part of our results section answers research questions about the three different forms of adapting the course design to the different needs of teachers and learners in physical and virtual learning environments (RQ 2) and our perception of this process (RQ 3). Therefore, we will describe the three teaching setups and their variations that we reconstructed retrospectively from our data and combine these descriptions with experiential accounts from our individual and dialogic reflections.

The sudden first lockdown in NZ accelerated the urge for developing suitable ways to conduct teaching and learning online and/or remotely. We identified three main teaching delivery setups that we developed as time progressed to include our students and staff geographically and spatially in our German classrooms during different stages of the pandemic. These approaches are a lockdown setup (1), a hybrid setup (2), and a blended setup (3).

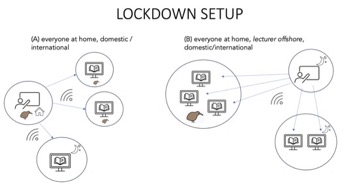

The lockdown Setup

In the first phase, an emergency remote teaching approach was launched by the UoA immediately after the first lockdown was announced in March 2020. The university established this teaching delivery mode within one week after the announcement of the lockdown, and beforehand teaching staff were provided with the necessary software, hardware (for lecturers onshore), and training. The specifics on how to implement emergency remote online teaching in each course were left to the discretion of the lecturers. We could identify two designs (A and B) that we developed during the lockdown set-up (see figure 1). This setup was implemented during the first national lockdown in 2020 and the Auckland lockdown in 2021.

Figure 1

Lockdown Setup

In design (A), the lecturer was onshore in NZ, teaching synchronously and structured by the time zone of NZ. This arrangement represents Diana’s teaching.

Also, in design (A) everyone was studying and teaching from their home. Students were either at home onshore in NZ, or offshore overseas. In the second year of the pandemic, Chinese students were also allowed to gather in one of two overseas learning centers. These learning centers were launched in 2021 in collaboration with Southwest University (SWU) in Chongqing and Northeast Forestry University (NEFU) in Harbin. This provided an alternative learning experience for Chinese students unable to enter NZ because of border restrictions. In total, about 1,000 students attended UoA courses remotely from China.[1]

In the second design (B) everyone was at home, but in contrast to (A), the lecturer (Mareike) was offshore, teaching from a different time zone and, therefore, under more challenging circumstances. She describes her situation in her reflection:

I was unable to enter the country before August 2022, I taught 2.5 semesters online, mostly at extremely late or incredibly early times in the day because of the time difference between my physical location and NZ. (Mareike, written reflection)

Design (B) was particularly challenging during the 2nd Auckland lockdown in 2021 because Mareike was offshore and the students, mainly located in East and Southeast Asia, were in an online-offshore stream. Initial timetabling scheduled the course during usual NZ course hours that were neither convenient for Mareike nor for her students because of different time zones:

It was also not considered that there was still a large number of offshore students who were not in the same time zone as the university. China is about six hours behind? Well, I think that worked well to some extent, but basically little consideration was given to it. I can remember that I agreed on a [different] time with the students for this offshore stream. […] Because basically, I didn’t care, the students didn’t care. There was no need for approval from the university. (Mareike, dialogic reflection, #00:11:38-3#)

This shows that Mareike regained her agency that she didn’t have during the timetabling process by independently adapting the course times according to her and the various students’ time zones, which allowed for their spatial inclusion and her teacher autonomy. Nevertheless, this experience was very challenging for Mareike being physically isolated from her workplace as she reflects in her written narrative:

Looking back now, I realize how nerve-wracking, frustrating, and overwhelming the time was. Besides living through a pandemic, being physically in a country that is on the opposite day-and-night rhythm than the country where you locate your professional actions is beyond challenging. However, firstly, not physically present at the location of my work, I still felt included by colleagues and relatively accommodated by university structures. Secondly, it made it easier for me to understand the challenges international students remaining offshore had to face and therefore felt a lot of compassion for them. (Mareike, written reflection)

In this account of Mareike’s perception of her experience we can see how her wellbeing was deeply affected by her workplace situation; however she developed resilience over time and also empathy for those students who were in the same situation.

The Hybrid Setup

Following the success of the NZ government’s measures to reduce the spread of the pandemic, the government started to ease measures domestically, though the country’s borders remained closed. These circumstances demanded a different approach to teaching and learning that we call a hybrid setup, where we combined online and on-campus teaching and learning (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Hybrid Setup

The hybrid setup also consisted of two different designs (A) and (B). We developed course delivery arrangement (A) once the campus opened again for students who were located in Auckland and did not need to self-isolate at home. Mareike taught from offshore, and students from various other countries and therefore time zones were included into the virtual classroom. Sometimes even the class time was adapted to fit better into the time zones of the offshore lecturer and students:

And I remember there was also a student in South Africa. He was based in, I think in Johannesburg. And that meant he was in almost the same time zone as I was in Germany back then. And whenever I had to teach at night, then he sat there at night too. […] So he was a really, really great, very motivated student. And then after a while he wrote to me, “Mareike, can we adapt this somehow? The online time? We have power cuts here.” So in Johannesburg there was still the problem, where he lived the electricity was turned off or there was only electricity at certain hours of the day (Mareike, dialogic reflection, translated, #00:12:58-0#)

This extract shows that the spatial inclusion in some cases was only possible if local aspects leading to a digital divide could be mitigated.

The hybrid setup A was also beneficial for students based in NZ but not in Auckland and this way could be included geographically:

At some point I wondered, why doesn’t he ever come to class [on campus]? And then he wrote me, no, I’m not in Auckland at all, I’m still in Hamilton. And that was a huge surprise to me, but in the end, it didn’t make any difference for me. I just kept looking after him online, right? […] Then there was Peter, who didn’t want to come to campus for health reasons. Totally legitimate. […] So in Language 102 there was no online stream, it was just the three people. I then offered them that we only meet once a week for an hour. […] Harry from Hong Kong and the two from New Zealand. Then we found a time that suited everyone and also suited me well. (Mareike, dialogic reflection #00:41:32-3#)

In variation A of the hybrid setup, it was sometimes possible to create small group sessions for remote students independent of their different time zones, so also allowed for more agency on Mareike’s side.

In design (B), Diana and Auckland-based students were on campus in an assigned classroom. Students offshore attended the course by using Zoom which was projected on the big screen in the room. The hybrid design continued to be implemented after the borders opened because many international students were not yet on campus due to delays in processing their visa applications. The hybrid setup allowed students to also participate in class online who were located in Auckland but had to self-isolate at home or had other reasons for not attending on-campus classes:

Mareike: (…) Aha, then it’s about the whole issue of online teaching. From students who are on site but not to campus. Don’t come to campus. #00:30:40-7#

Diana: Don’t want to come or just don’t come? #00:30:42-5#

Mareike: // Don’t want to. // There was a big problem. I remember one student; the ferries were canceled. That was coming from Gulf Harbour . It’s kind of an hour by ferry, right? And um. They then always talked about cancelled ferries (laughs). #00:30:56-7#

Diana: hm (affirmative) (…) Yes, right. Now also in the last year, like some who worked full time. And then didn’t want to come into the city for their classes. But preferred to participate online. #00:31:10-9#

Mareike: What did we do then? #00:31:12-5#

Diana: We made it possible. #00:31:13-6#

(translation, dialogic reflection #00:30:40-7 – 00:31:13-6#)

This extract shows how within these two models we tried to spatially include as many geographical locations as possible. Important here is the hybrid character in which teaching and learning happened on campus and remotely from home at the same time – domestically and internationally. This led to the combination of physical and virtual classrooms.

From a pedagogical point of view, the hybrid setup is the most demanding. We had to navigate tools for synchronous online teaching (e.g., web-conference software) to present the course content digitally. At the same time students on campus were gathering in an assigned classroom, and either used their own devices to participate in class and interact with the lecturer and students offshore, or they used the in-classroom computer to project the lecturer and the shared course content on the room’s screen. We had to take exceptional care when setting up group work as students’ geographical locations needed to be considered: students present on campus could work together, students online worked together in breakout rooms on Zoom.

The Blended Setup

In the second year of the pandemic, in September 2021, the UoA decided on transferring beginners’ courses of languages into a blended learning format to spark innovative models of teaching, but also to streamline language courses and to increase their viability by reducing staff workload. In this process we had to reduce our face-to-face teaching time from 100 minutes twice a week to 75 minutes twice a week (see figure 3).

Figure 3

Blended Setup

This design was developed for on campus delivery, not for online teaching. Therefore, the inclusion of remote students was neither intended nor feasible. To deliver content, we applied a flipped classroom approach and recorded learning videos in which we explain new grammar structures and vocabulary. These videos, recorded and hosted on Panopto (a video hosting platform), are supposed to be watched before attending each class. The courses at UoA are organized on Canvas, the web-based learning management system, through which videos, slides and other material are provided. In class, the focus is on practicing new structures and allowing interaction among students and between students and the lecturer.

After class, students are expected to invest their self-study time (10 hours/week) into doing their homework, familiarize themselves with additional online material and eventually watch the learning video for the next in-class session and work through the accompanying slides that include explanations and advise on learning strategies.

The preparational work on the blended learning initiative at the beginners’ level provided an opportunity for the geographical inclusion of Mareike from offshore, since she received teaching relief to focus on the development of the learning videos:

But I have to say that the work on the [blended learning] project finally relieved me, because (..) I was bought out of teaching Language 101. That means, I think I was teaching online at the time. And then I had my own personal time, which I could schedule myself when I was working on blended learning. And that was a huge relief for me, because I no longer had to get up at night, but could plan my time during the day, how to record the videos, the presentation, etc. and so on. So I was independent from the New Zealand time zone. (Mareike, dialogic reflection, 19:53)

In her retrospective reflection Mareike concludes that her geographical exclusion but spatial inclusion helped to improve her wellbeing and also to develop her teacher autonomy and professional development in online and blended language teaching:

Adapting to changing setups is beneficial not only to my own professional development, but also to the adaptation of teaching foreign languages to changing setups in the implementation of further developed learning and teaching technologies. [Mareike, written reflection]

In the following section we will discuss our findings and draw conclusions, especially focusing on the implications of our results.

Conclusion and Implications

In this duoethnography we explored our development of a spatially inclusive course design and our experiences with its implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic. We identified various factors that made geographical and spatial inclusion of remote students and teachers necessary. They mostly have to do with personal, socioeconomic, or geopolitical circumstances and the move to online teaching helped to include groups of students that would have otherwise been excluded from study opportunities. This form of inclusion stopped after the pandemic once the UoA decided to only allow for on-campus teaching of their courses. Nevertheless, in the space of language teaching, virtual teaching collaborations with other New Zealand universities are currently being trialed and could eventually lead to a return to a greater spatial inclusion (Author 1 & 2, in preparation). Furthermore, we also described the reasons for including remote teachers. Whereas including students in our courses was the focus, the applied setups also proved to include remote lecturers which led to more autonomy not only for learners but also for teachers.

In our study, we identified three course designs and four variations, depending on the location of the lecturer, that we developed during the Covid-19 pandemic: The lockdown setup, the hybrid setup, and the blended setup. From a post-pandemic perspective, the hybrid setup allows for the highest flexibility in location and also has a potential impact on course designs after the pandemic. However, this setup proves to be pedagogically the most challenging. Therefore, team-teaching might be beneficial for a course delivery model that equally includes on-campus and online students.

For the reflection of our course design experiences during the pandemic, we not only described the impacts on our wellbeing and resilience, but also observed that with the transition from emergency remote teaching to planned online/blended teaching within the given power dynamics, our agency was gradually regained. It allowed us as course coordinators to partially take control over the learning environment, where possible, to adapt setups to students’ various geographical locations, and therefore accommodate their learning circumstances and needs. Including students and lecturers alike, implementing varied dynamic setups increased our learners’ and teachers’ autonomy. Nevertheless, not all the three setups allow for the same grade of spatial inclusion and need to be carefully considered if this form of inclusion is seen as a priority.

Finally, in this study we introduced the concepts of geographical and spatial inclusion, which are necessary to describe an approach that we implemented as an impromptu reaction to a worldwide crisis but developed further to meet the needs of students and lecturers alike. In the future, we expect to see the demand for flexibility, location-independent learning, and (inter)national collaborations between universities continue to increase. Accordingly, the course setups presented will continue to gain relevance in our context.

This experience has also informed our perception of learner and teacher autonomy as well as inclusion from a post-pandemic perspective. Spatial inclusion (e.g., through digital technologies) should be incorporated in each teaching setting where not all learners are or can be at the same physical location, even if it is only temporary. Teacher autonomy needs to incorporate the agency to develop and implement teaching set ups that allow for a space-sensitive course delivery also at an ad-hoc basis. While all of our teaching at the UoA has returned to face-to-face delivery we think the inclusion of virtual learning spaces in primarily physical learning spaces could increase the learner autonomy, inclusivity and participation opportunities for otherwise (physically) excluded learners.

Notes on the Contributors

Diana Feick is Junior Professor in German as a Foreign and Second Language at the Friedrich Schiller University Jena in Germany. Her research areas are Digital Media in GfL, Mobile Language Learning, Virtual Exchange, Virtual Learning Spaces, Learner Autonomy, and Multimodal Language Learner Online Interaction.

Mareike Schmidt is a Professional Teaching Fellow for German at the University of Auckland as well as the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) representative in Aotearoa New Zealand. Mareike is interested in digital teaching, blended learning formats, project-oriented teaching, podcasting (hosting and implementing in teaching).

References

Benson, P. (2008). Teachers’ and learners’ perspectives on autonomy. In T. Lamb & H. Reinders (Eds.), Learner and teacher autonomy: Concepts, realities, and response (pp. 15–32). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/aals.1.05ben

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching: Autonomy in language learning. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833767

Benson, P. (2021). Language learning environments: Spatial perspectives on SLA. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/benson4900

Biebighäuser, K., Falk, S. Feick, D., & Schart, M. (2021) (Eds.), Info-DaF Themenheft: DaF im virtuellen Unterrichtsraum [Info-DaF special issue: DaF in the virtual classroom]. https://www.degruyter.com/journal/key/infodaf/48/5/html

Biebighäuser, K. (2022). Auswirkungen von Corona und zunehmender Digitalisierung auf das Deutschlernen und –lehren [Effects of Corona and increasing digitalization on learning and teaching German] GFL-German as a Foreign Language 1, 1–17. http://gfl-journal.de/article/auswirkungen-von-corona/

Biebricher, C., Feick, D., & Knorr, P. (2024). Interaktionsprozesse in einem virtuellen Austauschprojekt – duoethnographische Reflexionen der begleitenden Lehrpersonen [Interaction processes in a virtual exchange project – duoethnographic reflections by the accompanying facilitators]. Fremdsprachen lehren und lernen, 53(1). 27–42.

Blalock, A. E., & Akehi, M. (2018). Collaborative Autoethnography as a Pathway for Transformative Learning. Journal of Transformative Education, 16(2), 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344617715711

Burleigh, D., & Burm, S. (2022). Doing duoethnography: addressing essential methodological questions. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221140876

Feick, D. (2016). Autonomie in der Lernendengruppe: Entscheidungsdiskurs und Mitbestimmung in einem DaF-Handyvideoprojekt [Autonomy in the learner group: Decision-making discourse and participation in a German as a foreign language cell phone video project]. Narr.

Feick, D. (2018). Differenzierung weiterdenken: Lernortspezifik durch mobiles Lernen im Fremdsprachenunterricht [Think differentiation further: Learning specificity through mobile learning in foreign language teaching. Fremdsprachen lehren und lernen, 47(2). 84–98.

Feick, D. (2020). Digital und mobil – Befunde zur Nutzung mobiler Endgeräte im DaF-Unterricht der Sekundarstufe [Digital and mobile – findings on the use of mobile devices in German as a foreign language classes in secondary schools]. In K. Biebighäuser &, D. Feick (Eds.), Digitale Medien in Deutsch als Fremd- und Zweitsprache [Digital media in German as a foreign and second language] (pp. 43–68), Erich Schmidt Verlag.

Feick, D., & Knorr, P. (2021a). Mehrsprachigkeitsbewusstheit in digitalen Lernumgebungen: Das virtuelle Austauschprojekt „Linguistic Landscapes Leipzig – Auckland“. Language Education and Multilingualism – The Langscape Journal, 3, 135–157.

Feick, D., & Knorr, P. (2021b). Developing multilingual awareness through German-English online collaboration. In U. Lanvers, A. Thompson, & M. East (Eds.), Language learning in anglophone countries (pp. 331–358). Palgrave Macmillan.

Feick, D., & Knorr, P. (2022). Emotional aspects of online collaboration: Virtual exchange of pre-service EFL teachers. In G. Barkhuizen (Ed.): Language teachers studying abroad: Identities, emotions and disruptions (pp. 202–218). Multilingual Matters.

Feick, D., & Rymarczyk, J. (2022): Digitale Lernorte und -räume für das Fremdsprachenlernen [Digital learning places and spaces for foreign language learning]. In D. Feick, D., & J. Rymarczyk (Eds.), Zur Digitalisierung von Lernorten: Fremdsprachenlernen im virtuellen Raum [On the digitization of learning places: learning foreign languages in virtual space] (pp.7–44). Peter Lang.

Feick, D., & Tolosa, C. (forthcoming). Integration and perceptions of a language learning platform in New Zealand high schools.

Jiménez Raya, M., Manzano Vázquez, B., & Vieira, F. (2024). Bridging the gap between theory and practice in initial teacher education for autonomy In M. Jiménez Raya, B. Manzano Vázquez, & F. Vieira, F. (Eds), Pedagogies for autonomy in language teacher education. Perspectives on professional learning, identity, and agency (pp. 1–11). Routledge. https://doi-org.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/10.4324/9781003412021

Jung, I., Omori, S., Dawson, W. P., Yamaguchi, T., & Lee, S. J. (2021). Faculty as reflective practitioners in emergency online teaching: An autoethnography. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(30), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00261-2

Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2020). Mobile assisted language learning. In C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), The concise encyclopedia of applied linguistics (pp. 743–751). Wiley.

La Ganza, W. (2008). Learner autonomy – teacher autonomy. In T. Lamb & H. Reinders (Eds.), Learner and teacher autonomy: Concepts, realities, and response. (pp. 63–79). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/aals.1.08la

Lantolf, J. (2013). Sociocultural theory and the dialectic of L2 learner autonomy/agency. In P. Benson & L. Cooker (Eds.), The applied linguistic individual: Sociocultural approaches to identity, agency and autonomy (pp.17–31). Equinox.

Lawrence, L., & Lowe, R. J. (2020). An introduction to duoethnography. In R. J. Lowe & L. Lawrence (Eds.), Duoethnography in English language teaching: Research, reflection and classroom application (pp. 1–26). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788927192-003

Lay, T., & Feick, D. (2024). Deutsch als Fremd- und Fachsprache in Australien und Neuseeland [German as a foreign and technical language in Australia and New Zealand]. In M. Szurawitzki & P. Wolf-Farré (Eds.), Handbuch Deutsch als Fach- und Fremdsprache [Handbook of German as a Technical and Foreign Language]. (pp. 989–1003). De Gruyter.

Murray, G., & Lamb, T. (Eds) (2019). Space, place and autonomy in language learning. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781317220909-1

Nicolaides, C. (2017). Agency and empowerment towards the pursuit of sociocultural autonomy in language learning. In C. Nicolaides & W. Magno e Silva (Eds.), Innovations and challenges in applied linguistics and learner autonomy (pp. 19–41). Pontes Editores.

Norris, J., & Sawyer, R. (2012). Towards a dialogic method. In J. Norris, R. Sawyer, & D. Lund (Eds.), Duoethnography: Dialogic methods for social, health, and educational research (pp. 9–40). Left Coast Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315430058

Peña Clavel, M. A., Mynard, J., Liu, H., & Uzun, T. (2020). Introduction: Self-access and the coronavirus pandemic. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 11(3), 108–113. https://doi.org/10.37237/110301

Reinders, H., & Stockwell, G. (2017). Computer-assisted SLA. In S. Loewen & M. Sato (Eds.). The Routledge handbook of instructed second language acquisition (pp. 361–375). Routledge.

Ren, X. (2022). Autoethnographic research to explore instructional design practices for distance teaching and learning in a cross‑cultural context, TechTrends, 66, 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00683-9

Wilson, S., Tan, S., Knox, M., Ong, A., Crawford, J., & Rudolph, J. (2020). Enabling cross-cultural student voice during Covid-19: A collective autoethnography. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 17(5). https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol17/iss5/3/

[1] https://www.auckland.ac.nz/en/news/2020/05/28/university-of-auckland-launches-learning-centres-in-china-.html