Behnam Behforouz, University of Technology and Applied Sciences, Shinas, Oman

Ali Al Ghaithi, Sohar University, Oman

Behforouz, B. & Al Ghaithi, A. (2024). The impact of using interactive chatbots on self-directed learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(3), 317–344. https://doi.org/10.37237/150302

Abstract

The present study aimed to develop and implement an interactive chatbot in a language-learning setting. For this purpose, fifty Omani EFL students were divided into two equal groups: control and experimental. All the pretests were validated and piloted before the treatment to ensure practicality. The chatbot was designed using the WhatsApp platform, and instructions were given to the students. Some researcher-made tests, such as writing tasks, grammar, and reading comprehension activities, were assigned to both groups. In addition, an adapted questionnaire initially developed by Williamson (2007) was used as the pretest and posttest. The control group received all the materials using the traditional face-to-face teaching method, while the experimental group received all the instructions, explanations, and tests through the chatbot. The findings of the study revealed that the control group did not show any interest in completing the activities; on the contrary, the majority of participants in the experimental group engaged themselves in task achievements. Moreover, the self-directed learning questionnaire results showed that the experimental group progressed significantly from the pretest to the posttest in self-directed abilities, including awareness, learning strategies, activities, evaluation and interpersonal skills, with a statistically significant difference compared to the control group. The results of this study could be helpful for educators, students, and self-access centre staff.

Keywords: Chatbots, learner engagement, self-directed learning

Technological progress has enabled the integration of innovative educational approaches, such as the utilization of chatbots. Technological tools have the potential to significantly improve student participation and educational outcomes by creating opportunities for active instruction and the offering of tailored support (Diwanji et al., 2018; Gonda & Chu, 2019; Lin & Mubarok, 2021; Tangkittipon et al., 2020). Technology is crucial in enabling and supporting autonomous learning. Technological advances may directly impact self-directed learning by facilitating data acquisition and fostering digitized proficiency (Timothy et al., 2010).

The utilization of chatbots is critical for supplying tailored support to learners and enabling evaluation, feedback, and cooperation (Chen et al., 2021; Frangoudes et al., 2021; Kumar & Silva, 2020). Chatbots offer users an engaging and interactive environment by emulating conversations between people (Suhel et al., 2020). As a result, there has been significant momentum surrounding the incorporation of chatbots into the realm of instruction to enhance students’ scholastic performance (Baskara, 2023).

Chatbots have the potential to be employed in the field of education to generate dynamic and captivating educational resources and evaluations for learners. Chatbots have garnered considerable attention in the field of education due to their efficacy as an educational tool, which reflects the evolving nature of online education and its multifarious ramifications (Wijaya et al., 2018; Zulkarnain et al., 2020). Chatbots have recently been developed in education for an array of objectives. The swift progressions in technology have inspired language learners to assume greater responsibility for their academic pursuits beyond the confines of the conventional classroom setting (Başok & Sayer, 2020; Bernardo-Hinesley, 2020; Lee & Drajati, 2019; Nugroho & Atmojo, 2020). At this time, informal learning is facilitated by the abundance of leisure, resources, and learning spaces readily accessible in educational settings (Sundqvist & Sylvén, 2016). Customized educational settings and many chances for students to develop an awareness of independence in their educational endeavors are available (Bachmair & Pachler, 2014; Keefer & Haj-Broussard, 2020). Hence, in the present day, learners of languages hold a pivotal role in the realm of technological education; thus, motivating these individuals to participate in self-directed learning endeavors requires a thorough comprehension of their preferences concerning the ad hoc utilization of technological devices for learning intentions (Kalimullina et al., 2021; Shatunova et al., 2021).

Despite the extensive range of educational applications of AI, there continues to be a lack of fundamental knowledge concerning the integration of AI and its ramifications for education. Previous research on chatbots has primarily concentrated on improving educational outcomes and examining learners’ perceptions of chatbots. Nevertheless, these inquiries often neglect to offer clear and specific guidelines regarding the creation of chatbots that support individualized student learning experiences, particularly active learning and self-regulation (Lin, 2020). Lin proposed in his doctoral thesis a technique to develop a chatbot for educational settings, which would include knowledge tests and tailored feedback to guarantee the student recognizes the content.

Scholars of English as a Second Language have acknowledged that in the present age of technological benefits and developments, students engage in self-directed language learning outside of the traditional educational environment using a variety of electronic gadgets along with online materials (Sundqvist & Sylvén, 2016).

In conjunction with its fundamental self-assessment component, self-directed learning emphasizes that learners assume accountability for acquiring knowledge and aptitudes by initiating and overseeing their endeavors to recognize and address their learning requirements, objectives, procedures, and results. This student-led learning approach, which originated from the principles of adult education (Knowles, 1975), has become increasingly prevalent in education (Gibbons, 2003). In contrast, self-directed learning (SDL) encourages students to assume responsibility for their education by establishing objectives, tracking their advancement, and modifying approaches in light of feedback and introspection (Virtanen et al., 2017; Winne & Hadwin, 1998).

According to Nazmunissa and Rachman (2021), self-directed learning entails the student having absolute authority over the creativity, organization, implementation, and assessment of a given learning endeavor. All self-directed learning activities are at the students’ discretion; they may investigate methods for improving their English learning proficiency. Independent learning is how students demonstrate their desire to learn without depending on the assistance of others. Individually, students can engage in self-study, devise strategies for effective learning, locate learning tasks, and seek out learning activities.

Recently, Lee (2019) coined spontaneous online instruction of English to describe this self-directed language acquisition. The scope of this expression is broadened to include private English education activities conducted by students utilizing electronic gadgets (such as mobile phones, laptops, and tablets). Furthermore, it is worth noting that foreign language students often participate in productive and receptive activities, as Lee (2019) emphasized. The productive activities pertain to English language learning activities wherein students consume knowledge and information inactively (e.g., newscast reading and English video watching). On the other hand, receptive activities refer to English learning activities in which students effectively generate knowledge and skills (e.g., engaging in English conversations, responding to emails, or composing English-language remarks).

Prior research has investigated the perspectives, convictions, and notions of language learners regarding digital devices employed in pedagogical classroom experiments or trials (Agostinelli & McQuillan, 2020; Alzubi, 2019; Burston, 2014; Petersen et al., 2014; Smith & Wang, 2013; Solikhah & Budiharso, 2020; Sung et al., 2015). The findings indicate that students expressed favorable opinions regarding electronic tasks except for reservations regarding the absence of support in an independent setting to gain knowledge. Additionally, research has shown that students who were conducting learning activities outside of the classroom preferred desktop computers and laptops over mobile phones (Liu et al., 2015; Parker, 2019; Pollara & Broussard, 2011; Stockwell & Hubbard, 2013; Sylaj & Sylaj, 2020). Additionally, scholars have disclosed that students held electronic instruments in higher regard when participating in receptive language learning activities but were less favorable regarding their use to foster cooperation and integration into society in language communication (Chen, 2013; Dashtestani, 2016). Notably, the use of electronic tools by learners in their everyday lives, including using audio, viewing videos, and reading news online, is portrayed as a prevalent educational activity. This behavior takes precedence over other practices, such as engaging in communication practices, acquiring vocabulary, and performing grammar exercises (Arslan & Tanis, 2018; Bradley et al., 2017; Gapsalamov et al., 2020; Jones, 2015; Kustati & Al-Azmi, 2018; Viberg & Gronlund, 2013; Vural, 2019).

Thus, language learners’ perceptions regarding digital devices for language acquisition were presented with the topic of prior research. Nevertheless, most of the previous studies were carried out within the formal setting of a pedagogically designed classroom (Burston, 2014; Budiharso & Tarman, 2020; Lai et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2015; Petersen et al., 2014; Pollara & Broussard, 2011; Smith & Wang, 2013). Limited research has been conducted thus far on the voluntary adoption of digital devices by English learners for language development in contexts other than formal education (Govindasamy & Moi Kwe, 2020; Jones, 2015; Lai & Zheng, 2018; Viberg & Gronlund, 2013; White & Mills, 2014). However, these preliminary investigations into the learners’ engagement in utilizing electronic tools for learning in casual contexts could not delve deeply into the characteristics and varieties of digital learning experiences the students engaged in. Digitalized learning in an official setting is characterized by three distinct pedagogical framework aspects, as defined by Kearney et al. (2012): (1) personalization (the sense of ownership over the learning process); (2) authenticity (learning materials and tasks that are realistic and contextual); and (3) connectivity (collaborative learning and interconnectedness across temporal and spatial boundaries). Kearney et al. (2012) proposed pedagogical frameworks for digital learning that pertain to formal learning environments. Consequently, it is empirically questionable whether the same aspects of digital learning are evident in language learning outside of the classroom and require additional investigation.

Effective self-directed learning for younger students is influenced by two primary factors: internal “self” influences and external “other” influences. Personal characteristics, including motivation, self-regulation, and metacognition, are significant concerning internal “self” influences. Key determinants of external “other” influences in K-12 are learning environments, teaching and learning approaches, and teacher support. This is because K-12 students are younger and require greater direction regarding their education’s content, rationale, setting, and methodology (Van Deur, 2018). As described previously, the application targets these external “other” influences to circumvent classroom constraints. The position is that generative AI can serve as a personalized and on-demand external “other” influence that directs self-directed learning for younger students through dialogic interactions between humans and AI, anchored in well-established learning approaches. While present in various self-directed learning models, constructivist learning approaches typically serve as the basis for designing student-centred learning experiences that emphasize practical application and promote student agency (Brandt, 2020; Morris, 2019; Van Deur, 2018).

While some education has experimented with chatbots, language acquisition is one of the few domains in which they have been extensively embraced and enacted (Fryer et al., 2019; Winkler & Sollner, 2018). The use of chatbots to assist students in the learning process in higher education is uncommon (Vanichvasin, 2022). Utilizing the emergence of generic artificial intelligence (AI), this study designs and prototypes a program that can remotely assist users’ independent education and self-evaluation activities beyond educational settings. Interactive WhatsApp chatbot is a generative AI application OpenAI provides to implement in-context learning. This capability enables student-led learning to incorporate human-like interactions.

The present paper is an attempt to measure the role of an interactive chatbot designed through WhatsApp on students’ self-directed learning. Therefore, the following research question was formed:

Does implementing chatbots in the language learning process affect the degree of self-directed learning among Omani EFL learners?

Literature Review

Self-Directed Learning

The notion that students should be accountable for their schooling has acquired momentum in the fields of adult education and the field of educational psychology (under the term self-regulated learning [SRL]) over the past four decades (Carre, 2010; Cosnefroy, 2011; Saks & Leijen, 2014). Although there have been sporadic efforts to establish connections between the SDL and SRL, such as when SRL was applied to professional and adult education, these areas of study continue to be primarily distinct. A multitude of conceptual perspectives are cited, and a variety of research methods are implemented. We thus selected the SDL research perspective for this investigation, given that learning for adults is our subject of expertise (Cosnefroy, 2011; Milligan et al., 2015).

Two concepts can be used to define autonomous education (Candy, 1991): according to Knowles (1975, p. 18), education is a procedure whereby everyone proactively engages, with or without assistance from other people, in detecting their educational requirements, developing learning objectives, identifying pertinent material and human assets, selecting and executing suitable techniques for learning, and assessing their learning results. Additionally, a learner characteristic may pertain to a broad particular attribute or a particular aspect that is pertinent to how people learn. Self-directedness pertains to the educational procedures through which individuals assume principal accountability in learning scenarios, as understood within process-based concepts. The individual can affect and regulate by proactively establishing objectives, selecting tactics, and organizing, executing, and assessing the instructional process (Raemdonck et al., 2013).

The significance of SDL concerning student achievement in education in the twenty-first Century has been recognized. SDL has been associated with ongoing education. Both UNESCO and the OECD have recognized the importance of SDL in fostering a creative society. Additionally, studies examining self-direction among K -12 students have increased. In brief, self-direction has emerged as a critical skill for students in the twenty-first Century (Chee et al., 2011). Its direct involvement in using technology for learning within and beyond educational settings is now widely recognized. For example, digital storytelling is considered self-directed learning as an instructional approach (Ponhan et al., 2020).

Regarding self-directed learning, constructivist and humanistic philosophies hold divergent views (Morris, 2019). Early academic research defined self-directed learning as “major, a concerted effort to acquire specific knowledge and abilities (or to alter oneself in another way)” (Tough, 1971, p. 1). It is also an approach in which individuals determine their learning needs, create educational goals, identify supplies (materials and personnel), and select and implement materials (Knowles, 1975).

It is imperative to underscore that throughout history, two significant limitations in pivotal scholarly investigations concerning self-directed learning may have impeded the comprehension of its potential to foster innovative educational outcomes: (1) Neglecting the efficacy, practicality, or usefulness of the learning results generated by the approach; and (2) disregarding the fact that self-directed learning is predominantly a pragmatic methodology in the context of adult education (Morris, 2020). In particular, through rigorously structured interviews with sixty-six Canadian adults, Tough (1971) stated that self-directed learning is a common and functional characteristic of maturity that often functions in an efficient manner predominantly related to the professional life of an adult. A substantial research inquiry is being conducted regarding self-directed learning. Therefore, Tough (1971) considered self-directed learning to be pragmatic and life-focused. Nevertheless, a significant limitation of this study was the absence of data regarding the nature and effectiveness of the educational outcomes achieved through self-directed learning.

Although that term commonly refers to SDL, Knowles’s (1975) definition fails to prioritize realistic considerations of adult learning, according to a more comprehensive analysis. However, any educational study that could be executed as a nonpragmatic, isolated learning method might be considered the meaning of the definition (Guglielmino, 2008). Knowles (1975) did not emphasize the role of self-directed learning within a life-centered framework driven by the aspiration to surmount challenges encountered in practical situations. This may appear peculiar, given that Knowles (1975) stated in their work on andragogy that an essential principle of adult learning should be a feasible, purpose-driven procedure that aims to tackle challenges with tangible implications in actual life. Significantly, many empirical investigations concerning self-directed learning in various academic settings continue to be constructivist, disregarding the process’s pragmatic dimension (Lee et al., 2017).

Chatbots and Self-Directed Learning

There are some studies that have discussed the effects of chatbot on self-directed learning (Ait Baha et al., 2023; Baskara, 2023; Han et al., 2022; Pereira, 2016; Prondoza & Panoy, 2022; Sharma et al., 2022).

Ait Baha et al. (2023) created an instructional chatbot to assist 109 secondary school students as they studied Logo, a programming language. This study examined the potential of chatbots to augment learning experiences in contrast to conventional teaching methods. The students were assigned to two experimental groups, one receiving supplementary electronic resources and the other utilizing a chatbot, in addition to a control group that received traditional instruction. Questions gauging user satisfaction with the chatbot were administered in place of pretests and posttests to gauge the student’s knowledge gain. Insights were gained from the chatbot’s interactions, and data pertaining to its potential for content instruction, the challenges encountered by students, and its effects on enthusiasm, participation, and academic achievement were gathered. Additionally, the results indicated that implementing chatbot-based learning benefited students’ self-directed learning skills. According to the results, chatbots may enhance students’ academic achievement by facilitating self-paced, interactive education with individualized assistance.

Baskara (2023) investigated the correlation between chatbots and flexible learning in the academic context. Ethical and privacy matters associated with using chatbots in flexible learning environments were also discussed. A thorough investigation of the literature gathered from the Scopus and World of Science databases is a component of the theoretical evaluation methodology applied in this study. A qualitative methodology was applied to analyze the data gathered from a published study. In a flipped learning environment, chatbots may improve student participation and educational outcomes by providing personalized assistance, facilitation of discussion groups and cooperation, evaluation and feedback on student work, encouragement of self-directed learning, and enhancement of student inspiration and dedication, according to the study.

Han et al. (2022) designed and assessed the efficacy of a training course utilizing a chatbot powered by AI to enhance nursing students’ knowledge and proficiency in computerized fetal monitoring. This study included 61 junior nursing students at a university in South Korea. A pretest and posttest control group design was used in this study. Thirty students in the experimental group received instructional videos and an artificial intelligence chatbot program. Thirty students who only received lectures via video were included in the control group. The pretests and posttests were administered to assess the following variables: expertise, self-directed learning, self-assurance, rational thinking, passion for education, and input satisfaction. Although both groups demonstrated increased knowledge, the experimental group exhibited a notably greater inclination towards study and self-directed learning than the control group, according to the findings. The study concludes that chatbot programs have the potential to stimulate students’ curiosity and encourage independent studies effectively.

Prondoza and Panoy (2022) devised a method to improve the self-directed learning and scientific competencies of 35 grade 10 students in the Philippines by developing an interactive science chatbot. Utilizing ManyChat, the researchers constructed a chatbot and devised data collection instruments. The tests comprised a satisfaction questionnaire, pre-post science examination, and questionnaire on self-regulated learning skills. This study comprised a pilot examination, instrument validation, and chatbot development. Students employed the chatbot weekly for one month. Data were gathered using the instruments before and after using the chatbot. As evidenced by the increasing posttest ratings, the outcomes demonstrated that the chatbot helped enhance scientific competencies. The students’ self-regulation abilities, such as setting objectives and monitoring, were evident. According to the satisfaction questionnaires, feedback from the students regarding the chatbot’s functionality, substance, and language was overwhelmingly positive. The results suggest that engaging chatbots as additional material can significantly facilitate self-directed learning.

Sharma et al. (2022) created and deployed an AI chatbot named FLOKI to assist maritime students with their self-directed study of a chatbot named COLREG. The IBM Watson Advisor was used to develop the chatbot to answer inquiries on COLREG rules. This study included 18 second-year students. For the first twenty minutes, students engaged with FLOKI by posing questions on the chosen COLREG regulations. They then responded to a survey on FLOKI’s usability, the System Usability Scale (SUS). The SUS ratings showed that the FLOKI had excellent usability, with an average score higher than the pre-established threshold. Subsequent investigations revealed no discernible variation in SUS ratings between learners with previous chatbots or navigation experience. The study concluded that chatbot applications may improve students’ self-directed learning.

Pereira (2016) assessed using chatbots to enhance self-directed learning through conversational assessments. Twenty-three computer science students participated in this study. Over 15 weeks, students completed self-paced multiple-choice assessments of subjects covered in class using a Telegram assistant called @dawebot. In addition to storing student exam responses, the automaton delivers immediate input. A mind map and a dashboard application were created to monitor the development of students over time. Through a post-study survey, students were asked about their thoughts regarding using the automaton. According to these findings, although utilization increased near examinations, some students utilized the bot more frequently. Students viewed the assistant as user-friendly and believed its implementation in additional courses could facilitate learning. The instruments yielded valuable information regarding students’ comprehension at both the aggregate and individual levels.

Method

Participants

Fifty Omani first-year EFL students enrolled in a General English course in the Foundation Department were chosen randomly as the sample population of this study. They were divided into two equal groups: control and experiment. Everyone who participated spoke Arabic as their first language. The participants had pre-intermediate English proficiency levels. Each group included both genders, with 30 males and 20 females, with ages ranging from 18 to 20.

Instruments

Self-Rating Scale of SDL

This study employed the self-rating scale of SDL (SRSSDL) developed by Williamson (2007) to examine the progression of students’ SDL competencies. The scale included a concise student profile and fundamental instructions. Each of the five areas of SDL comprises 12 elements: (1) awareness, (2) learning strategies, (3) learning activities, (4) evaluation, and (5) interpersonal skills. The scale comprises 60 items organized into five categories. Each item was assigned a score of five for the ‘always’ response, while the ‘never’ response received a score of one. The maximum and minimum attainable SRSSDL ratings were 300 and 60, respectively. A scoring matrix was developed to aid in understanding the responses (Alshaye, 2021). The reliability of the SRSSDL scale was established as described by Salem (2022). The Cronbach alpha coefficients for strategies for learning, evaluation, interpersonal skills, and learning activities were all 0.87, 0.93, 0.91, and 0.88, respectively, for the entire scale. Numerous studies have employed this scale, as evidenced by Adnan and Sayadi (2021) and Lee (2020). Furthermore, multiple languages, including Italian, have been used to translate the scale (Cadorin et al., 2011). An Arabic translation of the scale is included in the present article. To verify that the Arabic iteration of the scale maintained consistent linguistic standards, format, and style, three PhD holders in Applied Linguistics who possessed substantial professional experience reviewed the questionnaire. Following this, an impartial moderator reviewed the survey to ensure its accuracy through query moderation and incorporation of academic and cultural ethics.

Assignments

To measure the progress of both groups in an educational environment and over the materials provided for the students, some reading, writing, and vocabulary exercises were assigned to them. In addition, the purpose of these activities was to measure the amount of engagement in completing these activities in the presence and absence of the treatments.

In the four weeks of teaching, both groups received two writing tasks every two weeks. Students had to write 150 words narrating a story and talking about their plans. There was no pressure on the students to complete these tasks obligatorily in either group. However, those students who submitted their assignments in the control group received face-to-face feedback. In contrast, those in the experimental group received automatic feedback through chatbots on general information like punctuation and grammar. Two PhD holders of Applied Linguistics, with 15 years of teaching and research experiences in Omani EFL learning and teaching contexts, confirmed the validity of the questions in two tasks.

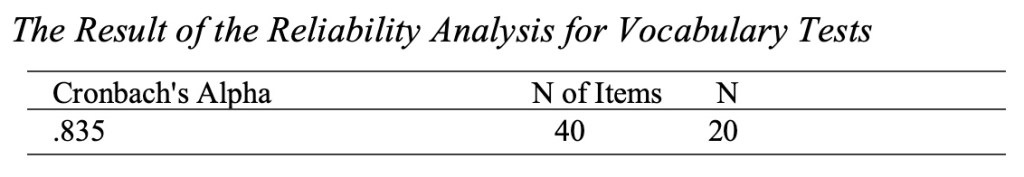

Four vocabulary activities were assigned to the students to complete every two days. Each vocabulary test had ten fill-in-the-blank activities to be completed. The words were either taught in a face-to-face situation, like in the control group, or with electronic chatbots in the experimental group. The reliability of these tests was measured in a piloting program with 20 Omani EFL learners from the same institution, and the results can be found in Table 1.

Table 1

The Result of the Reliability Analysis for Vocabulary Tests

As can be observed from the table above, the reliability of 40 vocabulary tests was revealed to be 0.835, which showed a high degree of reliability.

Finally, four reading activities were assigned to the students to complete. A reading text was followed by three true and false alternates, three one-word answers, and four fill-in-the-blanks activities. The reliability of these questions was measured through a pilot test with 20 students accordingly, and the following table reveals the results.

Table 2

The Result of the Reliability Analysis for Reading Comprehension Questions

As shown in Table 2, the reliability of the reading questions was 0.790, which shows the reliability of the questions.

English for the 21st Century 2 Edition Book Series

The investigators chose fifty phrases from the second version of English for the 21st Century. The textbook incorporated various skills and was instructed throughout the second academic term of 2023. This particular book served as the foundational text for university pre-intermediate-level students. The central focus of this investigation was units three and four. The study examined fifty terms to be instructed to students over two weeks, with 25 words each week.

WhatsApp Bot

Using Python language programming, an interactive chatbot was designed using WhatsApp to be implemented in this study among the participants in the experimental group. To measure the learners’ engagement in class activities and assignments, the experimental group received the instructions, and since the interactivity of the chatbot was added as a feature, students could receive immediate feedback on their work. A local number was associated with this chatbot. The researchers provided the essential tasks and the instructions in the chatbot database and updated them regularly based on the activities students had to complete.

Procedures

The research was conducted in 2024, during regular academic terms. Fifty students, a mixture of male and female individuals, were divided into two groups for this study: experimental and control groups. The voluntary nature of the study was explicitly communicated to participants. Both groups adhered to their instructors’ directives regarding the class activities and their roles; however, the experimental group had the opportunity to hone their skills beyond class time by utilizing the custom-built WhatsApp chatbot. An infinite number of repetitions of the queries were possible. The advisor guided the experimental group, outlined the steps to follow during technical difficulties, and illustrated the utilization of WhatsApp’s Bot for English-related activities.

Before the beginning of the treatment, both groups of students participated in a pretest of the Self-Directed Learning questionnaire to ensure the homogeneity of their answers in the absence of the treatment. During the four weeks of treatment, students in the control group followed their teachers’ instructions on the assignments, including vocabulary practice, reading, and writing exercises. The students were asked to do these tasks voluntarily, and it was emphasized that their engagement would not affect their official evaluation. Two writing tasks, four vocabulary exercises, and four reading tasks were assigned for the four weeks of training. The types of activities were commonly printed handouts prepared by the teacher, and the explanations were given in the class that the tasks were to be completed within two days. Although the same number and types of activities were assigned to the experimental group, the experimental group participants were given a local number to add to their WhatsApp and chat with the automated chatbot. The chatbots sent extra explanations and pictures to teach vocabulary again outside of class context; students were given additional explanations and examples on types of writing, format, and helpful discourse markers, and finally, for reading, the skills the techniques of finding keywords, were explained before exposing the students to the main task. This interactive bot sent the assigned activities the day after the instruction, and students were given an infinite number of repeating tasks but within the limitations of two days. The chatbots provided immediate feedback on the students’ correct or wrong answers.

After the four weeks of training with and without treatment in both groups, the students were given the self-directed learning questionnaire as the posttest. Simultaneously, students’ engagement in class activities in both groups was measured, too.

Data Analysis

To better understand the role of chatbots in self-directed learning, some data were collected from the students and analyzed thoroughly. The first part of this analysis investigates the number of tasks that students engaged in during the treatment period, as earlier mentioned, for a period of 4 weeks. The following bar charts show a visualization of these results.

Figure 1

Comparison of Control and Experimental Groups in the Number of Completed Assignments

As shown in Figure 1, 10 activities were assigned to the students to be completed voluntarily. It was mentioned earlier that each group has 25 members. To this end, the figure showed the experimental group’s highest engagement in the accomplishments of the activities. In writing activities, 12 essays were submitted by the control group participants, while 31 writing pieces were submitted in the experimental group. Regarding vocabulary, 53 activities were submitted in the control group for four assignments, while this number touched 86 activities in the experimental group. Finally, the data on reading revealed that 45 activities were completed successfully in the control group, while 87 activities were submitted through chatbots. The results found that those students who received the course instructions, explanations, activities, and feedback through chatbots showed better performance than their counterparts in the control group who were exposed to face-to-face instructions. It is worth noting that the engagement in all the abovementioned assignments was entirely voluntary, so students were the decision-makers on whether to complete or ignore the task.

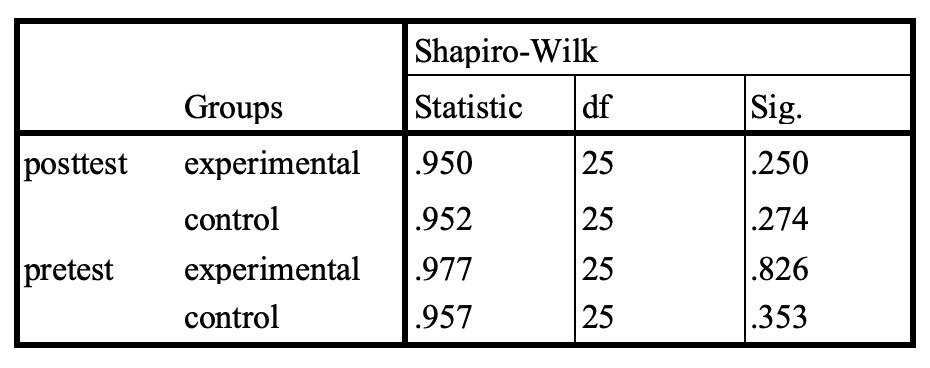

To deeply understand the impact of chatbots and direct instructions on students’ self-directed learning abilities, the pretest and posttest of SDL were analyzed in detail. Before verifying the associated research hypothesis, it was imperative to ascertain whether the data distribution for both the pretest and posttest followed a normal pattern. The researcher performed a Shapiro-Wilk test for this purpose. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3

The Result of the Shapiro-Wilk Test of Normality

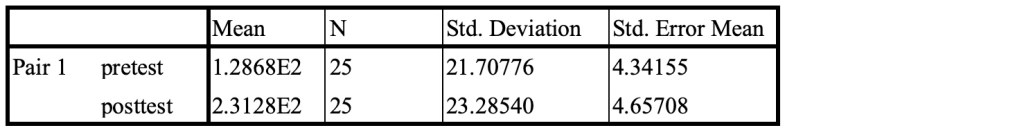

As Table 3 shows, the normal distribution of the tests was confirmed for all sets of the tests because p> .05. Therefore, to compare the results within the groups, a paired sample t-test was conducted, and to measure the groups together, an independent sample t-test was selected confidently. Tables 4 and 5 below show the descriptive analysis and paired-sample t-test of the pretest and posttest of the control group on SDL.

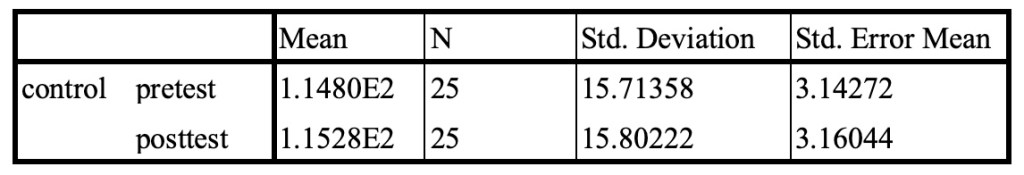

Table 4

The Descriptive Analysis of SDL in the Pretest and Posttest of Control Group

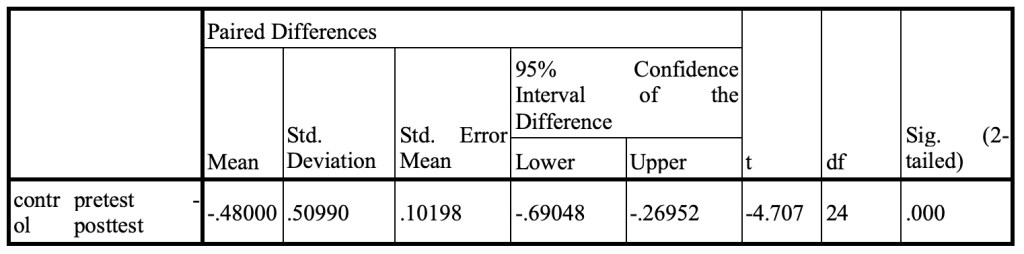

Table 5

The Results of Paired-Sample T-Test of SDL in Pretest and Posttest of Control Group

As shown in Table 4, the mean scores of participants in the control group are very close to each other in the pretest and posttest, 1.148 and 1.152, respectively. Although Table 5 shows that at df: 24, the sig is 0.000, which is lower than the P-value (p<0.05), which leads to this statement that there was progress from the pretest to the posttest, the mean scores comparison of the pretest and posttest showed that this progress was not highly remarkable. So, it could be concluded that this small progress resulted from in-class training within one month.

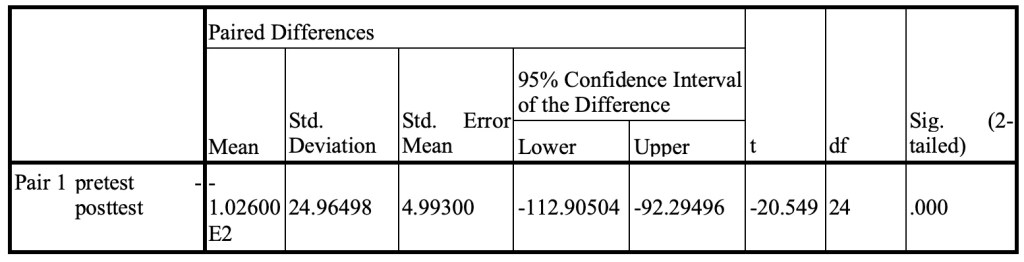

A paired-sample t-test was conducted to gain a better understanding of the results of the experimental group.

Table 6

The Descriptive Analysis of SDL in the Pretest and Posttest of the Experiment Group

As Table 6 revealed, the means comparison of participants in the experiment group shows a remarkable difference from pretest to posttest. To know the size of this difference, a paired-sample t-test was conducted, and the following results were revealed.

Table 7

The Results of Paired-Sample T-Test in Pretest and Posttest of Experiment Group

As could be observed in Table 7, at df = 24, the sig. is 0.000, and since the p<0.05, it could be concluded that the experimental group experienced statistically significant progress in self-directed learning from the pretest to the posttest.

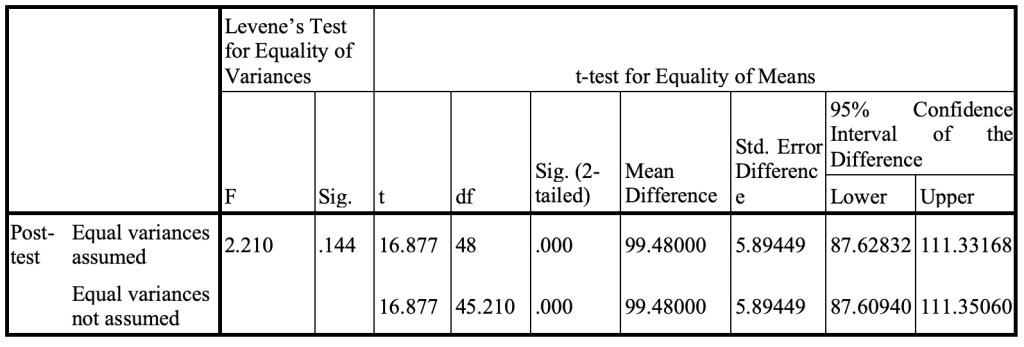

Finally, to measure the differences between the control and experimental groups, an independent sample t-test was conducted.

Table 8

The Descriptive Analysis of Experimental and Control Groups in Posttest

As the descriptive statistics of Table 8 suggested, the mean scores of experimental and control groups are 2.31 and 1.31, respectively. It can be inferred that the experimental group performed better than their counterparts in the control group. However, the independent t-test results could be used accordingly to confirm the former statement confidently.

Table 9

The Results of an Independent T-Test between the Experimental and Control Groups

The results of Table 9 revealed that the variances may be unequal; the t-test results are highly significant, with a very big difference in means between the two groups: t = 16.877; df = 45.210; p-value < 0.001. The mean difference is 99.48, with a standard error difference of 5.89449. The 95% Confidence Interval, ranging from approximately 87.61 to 111.35, suggests that there is a large statistically significant difference in posttest scores between the groups when equal variances are not assumed.

Discussion

The present research analyzed the impact of the interactive WhatsApp chatbot on self-directed learning among Omani EFL learners. In this study, with two groups, the control group received the assignments and instructions in the class, while the experimental group received all the materials through interactive chatbots. Some voluntary tasks were assigned to students of both groups. It was revealed that experimental group participants completed more tasks than learners in the control group. In addition, the results of self-directed learning showed that at the end of treatment, participants of the experimental group showed a high degree of independence in the language learning process compared to their counterparts in the control group. Primarily, interactive chatbots augment student involvement by offering instant feedback, tailored material, and a conversational interface, so rendering the learning experience more captivating and inspiring. This level of involvement probably played a role in the increased task completion rates observed in the experimental group. Moreover, the ease and availability of accessing educational content through WhatsApp at any time and location may have allowed students in the experimental group to interact with learning materials more often and regularly compared to those in the control group, who only received materials during class.

In addition, interactive chatbots facilitate self-directed learning by motivating students to proactively engage in their studies, establish their objectives, and efficiently allocate their time. The autonomy demonstrated in the experimental group may have contributed to the heightened independence noticed. This is because students were able to engage with the chatbot at their speed, which in turn cultivated a feeling of ownership and accountability for their learning. The introduction and the contemporary nature of employing chatbots for educational purposes may have also heightened motivation, as students experienced a greater sense of autonomy and ability to guide their learning journey.

Ultimately, the customized educational experience provided by chatbots, which can adjust to the specific requirements of each learner, probably bolstered the sense of support and competence among students in the experimental group, so further improving their self-directed learning abilities. These principles correspond to modern educational theories that prioritize learner-centred methods, active participation, and the cultivation of independent learning abilities, therefore providing a rationale for the observed results in the experimental group.

The findings of this investigation align with a study by Ait Baha et al. (2023), who investigated the capacity of avatars to enhance learning experiences. The principal finding of this study was that the integration of chatbot-based learning positively influences the development of students’ self-directed learning abilities.

In a study with similar findings, Baskara (2023) examined the correlation between chatbots and flexible learning in an academic setting. According to the results of this study, chatbots increased student engagement and academic achievement in a flipped learning environment by facilitating partnerships and group discussions, providing personalized assistance, assessing and providing feedback on student work, promoting self-directed learning, and bolstering student motivation and commitment.

The results of this study are consistent with the research conducted by Han et al. (2022), in which they evaluated the effectiveness of an AI-powered chatbot-based training program for nursing students to improve their understanding and skills in the automated monitoring of fetal development. Sixty-one junior nursing students from a South Korean university participated in the study. The results of the research demonstrated that the experimental group demonstrated a significantly higher propensity for studying and engaging in self-directed learning than the control group.

In another similar study, Prondoza and Panoy (2022) created a strategy to enhance the self-directed learning and scientific abilities of thirty-five tenth-grade students in the Philippines. The investigators developed a chatbot and formulated the data collection instruments by utilizing ManyChat. The findings of this study indicated that incorporating interactive chatbots as supplementary resources could effectively promote self-directed learning to a considerable extent.

Additionally, a study conducted by Pereira (2016) used interactive assessments to evaluate the efficacy of chatbots in promoting self-directed learning. Twenty-three students majoring in computer science were involved in this research. Based on the research results, while usage peaked in the days leading up to exams, certain students employed the bot more frequently than others. Students who believed its integration into further courses could enhance and engage in the learning process perceived the assistant favorably.

In another research conducted by chatbot specialists (Chang et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2020), it was revealed that implementing chatbot-based learning significantly improved participants’ academic performance. Consistent with the results of the present study, Abbasi and Kazi (2014) discovered that students who utilized chatbots during the learning process achieved exceptional memory retention and learning outcomes. The results of this research both support and refute the conclusions drawn by Sabiq and Fahmi (2020). They discovered that the chatbot functioned effectively as a supplementary teacher assistance in an academic setting. They assist instructors in facilitating the distribution of course materials and evaluations. The researchers hypothesized that supplementing teacher-led instruction with chatbots would increase students’ excitement and engagement in the educational process.

However, this study’s results are inconsistent with those of Yin et al. (2020), who conducted research utilizing chatbot learning to assess students’ drive and achievement. Despite the study demonstrating enhancements in students’ learning environments, these findings were not statistically significant.

Conclusion

The findings of this investigation into using WhatsApp chatbot for English language instruction and learning are encouraging. It was concluded that implementing these algorithms would aid the process of gaining learning autonomy. Statistical analysis of the experimental group’s student achievement indicated that obtaining guidelines via WhatsApp chatbot significantly impacted self-directed learning and taking learning responsibilities toward being more independent learners. Concurrently, the research may have a few consequences for educators and students. Educators have the ability to utilize these automated systems to provide supplementary resources, materials, or instructions to their students. This is because technology and AI have become indispensable components of everyday life and educational spheres. By enabling easy, tailored, and engaging learning experiences, chatbots may greatly augment the independence and drive of learners. Through the careful evaluation of user-friendliness, feedback mechanisms, and content relevancy, educational institutions may fully utilize the capabilities of chatbots to provide dynamic and supportive self-access learning environments that promote learner autonomy and engagement.

However, there are limitations, concerns, and recommendations for future research in this study.

- Because the sample of this research comprised Omani EFL candidates enrolled in one of Oman’s academic institutions, its generalizability is limited. Incorporating additional proficiency levels of students, including those in upper intermediate, advanced, and higher education, into creating technological instruments for education will yield more comprehensive outcomes. Furthermore, given that each institution possesses its technological infrastructure and devices conducting additional research in different regions of Oman or any other nation could yield a more accurate depiction of the impact of technology on education.

- WhatsApp bot was used to measure self-directed learning in the present study. Additional research should be conducted to determine the efficacy of bots in different programs, such as Messenger. Furthermore, possessing other skills, including but not limited to grammar, punctuation, and writing, can be advantageous.

- Finally, this automaton served as the host’s unidirectional instruction for the students. It would be ideal if additional interactive bots were developed so that students could converse and have their language outputs and errors evaluated further.

Notes on the Contributors

Behnam Behforouz is an English Lecturer in the Preparatory Studies Center at University of Technology and Applied Sciences, Shinas, Oman. His main areas of interest are TESOL, Language Education, and Educational Technologies.

Ali Al Ghaithi is an English Lecturer at Foundation Department of Sohar University in Oman. Currently, he is a Ph.D. candidate in Applied Linguistics. Ali is interested in research studies focusing on Artificial Intelligence in teaching and learning processes.

References

Abbasi, S., & Kazi, H. (2014). Measuring effectiveness of learning chatbot systems on student’s learning outcome and memory retention. Asian Journal of Applied Science and Engineering, 3(7), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.15590/ajase/2014/v3i7/53576

Adnan, N. H., & Sayadi, S. S. (2021). ESL students’ readiness for self-directed learning in improving English writing skills. Arab World English Journal, 12(4), 503–520. https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol12no4.33

Agostinelli, A., & McQuillan, P. (2020). How preservice content teacher background qualities influence their attitude and commitment to supporting multilingual learners. Journal of Curriculum Studies Research, 2(2), 98–121. https://doi.org/10.46303/jcsr.2020.12

Ait Baha, T., El Hajji, M., Es-Saady, Y., & Fadili, H. (2023). The impact of educational chatbot on student learning experience. Educational Information Technology, 29, 10153–10176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-12166-w

Alshaye, S. (2021). Digital storytelling for improving critical reading skills, critical thinking skills, and self-regulated learning skills. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 16(4), 2049–2069. https://doi.org/10.18844/cjes.v16i4.6074

Alzubi, A. (2019). Teachers’ perceptions on using smartphones in English as a foreign language context. Research in Social Sciences and Technology, 4(1), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.46303/ressat.04.01.5

Arslan, C., & Tanis, B. M. (2018). Building English vocabulary schema retention using review value calculation for ESL students. Research in Social Sciences and Technology, 3(3), 116–134. https://doi.org/10.46303/ressat.03.03.7

Bachmair, B., & Pachler, N. (2014). A cultural ecological frame for mobility and learning. MedienPädagogik: Zeitschrift Für Theorie Und Praxis Der Medienbildung, 24, 53–74. https://doi.org/10.21240/mpaed/24/2014.09.04.X

Baskara, F. R. (2023). Chatbots and flipped learning: Enhancing student engagement and learning outcomes through personalized support and collaboration. International Journal of Recent Educational Research, 4(2), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.46245/ijorer.v4i2.326

Başok, E., & Sayer, P. (2020). Language ideologies, language policies and their translation into Fiscal policies in the US perspectives of language education community stakeholders. Journal of Culture and Values in Education, 3(2), 54–80. https://doi.org/10.46303/jcve.2020.13

Bernardo-Hinesley, S. (2020). Linguistic landscape in educational spaces. Journal of Culture and Values in Education, 3(2), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.46303/jcve.2020.10

Bradley, L., Lindström, N. B., & Hashemi, S. S. (2017). Integration and language learning of newly arrived migrants using mobile technology. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2017(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.434

Brandt, W. C. (2020). Measuring student success skills: A review of the literature on self-directed learning. National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment.

Budiharso, T., & Tarman, B. (2020). Improving quality education through better working conditions of academic institutes. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, 7(1), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejecs/306

Burston, J. (2014). The reality of MALL: Still on the fringes. Calico Journal, 31(1), 103–125. https://doi.org/10.11139/cj.31.1.103-125

Cadorin, L., Suter, N., Saiani, L., Naskar Williamson, S., & Palese, A. (2011). Self-rating scale of self-directed learning (SRSSDL): Preliminary results from the Italian validation process. Journal of Research in Nursing, 16(4), 363–373. https://doi.org/d5gxkt

Candy, P. C. (1991). Self-direction for lifelong learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Chang, C. Y., Kuo, S. Y., & Hwang, G. H. (2022). Chatbot-facilitated nursing education: incorporating a knowledge-based chatbot system into a nursing training program. Educational Technology & Society, 25(1), 15–27.

Chee, T. S., Divaharan, S., Tan, L., & Mun, C. H. (2011). Self-directed learning with ICT: Theory, practice and assessment. Ministry of Education.

Chen, X.-B. (2013). Tablets for informal language learning: Student usage and attitudes. Language Learning & Technology, 17(1), 20–36. http://dx.doi.org/10125/24503

Chen, H. L., Vicki Widarso, G., & Sutrisno, H. (2020). A chatbot for learning Chinese: Learning achievement and technology acceptance. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 58(6), 1161–1189. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633120929

Chen, X., Zou, D., Xie, H., & Cheng, G. (2021). Twenty years of personalized language learning. Educational Technology & Society, 24(1), 205–222.

Cosnefroy, L. (2011). L’apprentissage autorégulé: Entre motivation et cognition [Self-regulated learning: Between motivation and cognition]. Presses Universitaires de Grenoble.

Dashtestani, R. (2016). Moving bravely towards mobile learning: Iranian students’ use of mobile devices for learning English as a foreign language. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(4), 815–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2015.1069360

Diwanji, P., Hinkelmann, K., & Witschel, H. (2018). Enhance classroom preparation for flipped classroom using AI and analytics. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems – Volume 1: ICEIS, 477–483. SciTePress. https://doi.org/10.5220/0006807604770483

Frangoudes, F., Hadjiaros, M., Schiza, E. C., Matsangidou, M., Tsivitanidou, O., & Neokleous, K. (2021). An overview of the use of chatbots in medical and healthcare education. Learning and Collaboration Technologies: Games and Virtual Environments for Learning: 8th International Conference, LCT 2021 (pp. 170–184). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77943-6_11

Fryer, L. K., Nakao, K., & Thompson, A. (2019). Chatbot learning partners: Connecting learning experiences, interest and competence. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 279–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.023

Gapsalamov, A.R., Bochkareva,T.N., Vasilev, V.L., Akhmetshin, E.M. & Tatyana Ivanovna Anisimova, T.I. (2020). Comparative analysis of education quality and the level of competitiveness of leader countries under digitalization conditions. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 11(2), 133–150. https://jsser.org/index.php/jsser/article/view/1737/450

Gibbons, P. (2003). Mediating language learning: Teacher interactions with ESL students in a content-based classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 37(2), 247–273.

Gonda, D. E., & Chu, B. (2019). Chatbot as a learning resource? Creating conversational bots as a supplement for teaching assistant training course. 2019 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Education (TALE), (pp. 1–5). https://doi.org/10.1109/TALE48000.2019.9225974

Govindasamy, K., & Moi Kwe, N. (2020). Scaffolding problem solving in teaching and learning: The DPACE model – A design thinking approach. Research in Social Sciences and Technology, 5(2), 93–112. https://doi.org/10.46303/ressat.05.02.6

Guglielmino, L. M. (2008). Why self-directed learning? International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 5(1), 1–14.

Jones, A. (2015). Mobile informal language learning: Exploring Welsh learners’ practices. eLearning Papers, 45, 4–14.

Han, J. W., Park, J., & Lee, H. (2022). Analysis of the effect of an artificial intelligence chatbots educational program on non-face-to-face classes: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03898-3

Kalimullina, O., Tarman, B. & Stepanova, I. (2021). Education in the context of digitalization and culture: Evolution of the teacher’s role, pre-pandemic overview. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, 8(1), 226–238. http://dx.doi.org/10.29333/ejecs/629

Kearney, M., Schuck, S., Burden, K., & Aubusson, P. (2012). Viewing mobile learning from a pedagogical perspective. Research in Learning Technology, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v20i0.14406

Keefer, N., & Haj-Broussard, M. (2020). Language in educational contexts. Journal of Culture and Values in Education, 3(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.46303/jcve.2020.9

Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Cambridge Adult Education.

Kumar, J. A., & Silva, P. A. (2020). Work-in-progress: A preliminary study on students’ acceptance of chatbots for studio-based learning. 2020 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), 1627–1631. https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON45650.2020.9125183

Kustati, M., & Al-Azmi, H. (2018). Pre-Service teachers’ attitude on ELT research. Research in Social Sciences and Technology, 3(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.46303/ressat.03.02.1

Lai, C., Wang, Q., Li, X., & Hu, X. (2016). The influence of individual espoused cultural values on self-directed use of technology for language learning beyond the classroom. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.04.039

Lai, C., & Zheng, D. (2018). Self-directed use of mobile devices for language learning beyond the classroom. ReCALL, 30(3), 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344017000258

Lee, C., Yeung, A. S., & Ip, T. (2017). University English language learners’ readiness to use computer technology for self-directed learning. System, 67, 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.05.001

Lee, J. S. (2019). Quantity and diversity of informal digital learning of English. Language Learning & Technology, 23(1), 114–126. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/44675

Lee, J. S., & Drajati, N. A. (2019). English as an international language beyond the ELT classroom. ELT Journal, 73(4), 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccz018

Lee, J. W. (2020). Analysis of EFL learners’ argumentative writing using the adapted Toulmin model. English Language & Literature Teaching, 26(3), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.35828/etak.2020.26.3.63

Lin, M. P. C. (2020). A proposed methodology for investigating chatbot effects in peer review [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Simon Fraser University.

Lin, C. J., & Mubarok, H. (2021). Learning analytics for investigating the mind map-guided AI chatbot approach in an EFL flipped speaking classroom. Educational Technology & Society, 24(4), 16–35.

Liu, G. Z., Kuo, F. R., Shi, Y. R., & Chen, Y. W. (2015). Dedicated design and usability of a context-aware ubiquitous learning environment for developing receptive language skills: a case study. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation, 9(1), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijmlo.2015.069717

Milligan, C., Fontana, R. P., Littlejohn, A., & Margaryan, A. (2015). Self-regulated learning behaviour in the finance industry. Journal of Workplace Learning, 27(5), 387–402. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-02-2014-0011

Morris, T. H. (2019). Adaptivity through self-directed learning to meet the challenges of our ever-changing world. Adult Learning, 30(2), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045159518814486

Morris, T. H. (2020). Creativity through self-directed learning: Three distinct dimensions of teacher support. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 39(2), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2020.1727577

Nazmunissa, N., & Rachman, G.A. (2021). Learning English independently through social media during the covid-19 pandemic. Prosiding Seminar Nasional Ilmu Pendidikan dan Multidisiplin, 4, 94–97.

Nugroho, A., & Atmojo, A. E. P. (2020). Digital learning of English beyond classroom: EFL learners’ perception and teaching activities. JEELS (Journal of English Education and Linguistics Studies), 7(2), 219–243. https://doi.org/10.30762/jeels.v7i2.1993

Parker, J. (2019). Second language learning and cultural identity. Journal of Curriculum Studies Research, 1(1), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.46303/jcsr.01.01.3

Petersen, S. A., Procter-Legg, E., & Cacchione, A. (2014). LingoBee: Engaging mobile language learners through crowd-sourcing. International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning (IJMBL), 6(2), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijmbl.2014040105

Pollara, P., & Broussard, K. K. (2011). Student perceptions of mobile learning: A review of current research. Proceeding of the Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference 2011. Chesapeake, VA: AACE, 1643–1650.

Pereira, J. (2016). Leveraging chatbots to improve self-guided learning through conversational quizzes. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality (pp. 911–918). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3012430.3012625

Ponhan, S., Inthapthim, D., & Teeranon, P. (2020). An investigation of EFL students’ perspectives on using digital storytelling to enhance self-directed learning: A case study of EFL Thai learners. Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences, 18(1).

Prondoza, G. R., & Panoy, J. F. (2022). Development of chatbot supplementary tool in science and the self-regulated learning skills among the grade 10 students. Asia Pacific Journal of Advanced Education and Technology, 107–116. https://doi.org/10.54476/apjaet/95445

Raemdonck, I., Meurant, C., Balasse, J., Jacot, A., & Frenay, M. (2013). Exploring the concept of ‘self-directedness in learning’: Theoretical approaches and measurement in adult education literature. In D. Gijbels, V., Donche, J.T.E. Richardson, J.D. Vermunt (Eds.), Learning Patterns in Higher Education: Dimensions and Research Perspectives (pp. 78-101). Routledge.

Sabiq, A. H. A., & Fahmi, M. I. (2020). Mediating quizzes as assessment tool through WhatsApp auto-response in ELT online class. Langkawi: Journal of The Association for Arabic and English, 6(2), 186–201. https://doi.org/10.31332/lkw.v6i2.2216

Saks, K., & Leijen, Ä. (2014). Distinguishing Self-directed and self-regulated learning and measuring them in the e-learning context. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 112, 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.1155

Salem, A. A. M. S. (2022). Multimedia presentations through digital storytelling for sustainable development of EFL learners’ argumentative writing skills, self-directed learning skills and learner autonomy. Frontiers in Education, 7, 884709. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.884709

Sharma, A., Undheim, P. E., & Nazir, S. (2022). Design and implementation of AI chatbot for COLREGs training. WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13437-022-00284-0

Shatunova, O., Bozhkova, G., Tarman, B., & Shastina E. (2021). Transforming the reading preferences of today’s youth in the digital age: Intercultural dialog. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, 8(3), 62–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.29333/ejecs/347

Smith, S., & Wang, S. (2013). Reading and grammar learning through mobile phones. Language Learning & Technology, 17(3), 117–134.

Solikhah, I., & Budiharso, T. (2020). Exploring cultural inclusion in the curriculum and practices for teaching bahasa Indonesia to speakers of other languages. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 11(3), 177–197. https://jsser.org/index.php/jsser/article/view/2658

Stockwell, G., & Hubbard, P. (2013). Some emerging principles for mobile-assisted language learning. The International Research Foundation for English Language Education, 1–15.

Suhel, S. F., Shukla, V. K., Vyas, S., & Mishra, V. P. (2020). Conversation to automation in banking through chatbot using artificial machine intelligence language. 2020 8th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimisation (Trends and Future Directions)(ICRITO), 611–618. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRITO48877.2020.9197825

Sundqvist, P., & Sylvén, L. K. (2016). Extramural English in teaching and learning: From theory and research to practice. Palgrave Macmillan.

Sung, Y.-T., Chang, K.-E., & Yang, J.-M. (2015). How effective are mobile devices for language learning? A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 16, 68–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.09.001

Sylaj, V., & Sylaj, A.K. (2020). Parents and teachers’ attitudes toward written communication and its impact in the collaboration between them: Problem of social study education. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 11(1), 1–20. Retrieved from https://jsser.org/index.php/jsser/article/view/1649/435

Tangkittipon, P., Sawatdirat, A., Lakkhanawannakun, P., & Noyunsan, C. (2020). Facilitating a flipped classroom using chatbot: A conceptual model. Engineering Access, 6(2), 103–107. http://doi.org/10.14456/mijet.2020.20

Timothy, T., Seng Chee, T., Chwee Beng, L., Ching Sing, C., Joyce Hwee Ling, K., Wen Li, C., & Horn Mun, C. (2010). The self-directed learning with technology scale (SDLTS) for young students: An initial development and validation. Computers & Education, 55(4), 1764–1771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.08.001

Tough, A. (1979). The adult’s learning projects: A fresh approach to theory and practice in adult learning (2nd ed.). Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Van Deur, P. (2018). Managing self-directed learning in primary school education: Emerging research and opportunities. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-2613-1

Vanichvasin, P. (2022). Impact of chatbots on student learning and satisfaction in the entrepreneurship education programme in higher education context. International Education Studies Archives, 15(6). https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v15n6p15

Viberg, O., & Grönlund, Å. (2013). Cross-cultural analysis of users’ attitudes toward the use of mobile devices in second and foreign language learning in higher education: A case from Sweden and China. Computers & Education, 69, 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.07.014

Virtanen, H., Björk, P., & Sjöström, E. (2017). Follow for follow: marketing of a start-up company on Instagram. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(3), 468–484. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-12-2016-0202

Vural, H. (2019). The relationship of personality traits with English speaking anxiety. Research in Educational Policy and Management, 1(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.46303/repam.01.01.5

White, J., & Mills, D. J. (2014). Examining attitudes towards and usage of smartphone technology among Japanese university students studying EFL. CALL-EJ, 15(2), 1–15.

Wijaya, M. H., Sarosa, M., & Tolle, H. (2018). Rancang bangun chatbot pembelajaran Java pada Google Classroom dan Facebook Messenger [Design and build a Java learning chatbot on Google Classroom and Facebook Messenger]. Jurnal Teknologi Informasi Dan Ilmu Komputer, 5(3), 287. https://doi.org/10.25126/jtiik.201853837

Williamson, S. N. (2007). Development of a self-rating scale of self-directed learning. Nurse Researcher, 14, 66–83. http://dx.doi.org/10.7748/nr2007.01.14.2.66.c6022

Winkler, R., & Soellner, M. (2018). Unleashing the potential of chatbots in education: A state-of-the-art analysis. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2018(1), Article 15903. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2018.15903abstract

Winne, P. H., & Hadwin, A. F. (1998). Studying as self-regulated learning. In Metacognition in educational theory and practice, (pp. 277-304). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Yin, J., Goh, T., Yang, B., & Xiaobin, Y. (2020). Conversation technology with micro-learning: The impact of chatbot-based learning on students’ learning motivation and performance. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 59(1), 154-177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633120952067

Zulkarnain, M. A., Raharjo, M. F., & Olivya, M. (2020). Perancangan aplikasi chatbot sebagai media e-learning bagi siswa [Design of chatbot applications as e-learning media for students]. Elektron : Jurnal Ilmiah, 12(2), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.30630/eji.12.2.188