Larissa Borges, Language Department, Federal University of Pará, Brazil

Borges, L. (2023). The “Complex Dynamic Model of autonomy development” in action: A longitudinal multiple case study on language learners’ trajectories. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.37237/150104

Abstract

This paper explores the autonomy development in the language learning trajectories of two English major students within the complexity paradigm (Larsen-Freeman, 1997, 2017; Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008). Autonomy is viewed as a complex, evolving phenomenon shaped by life experiences, including setbacks, stability, and progress. The Complex Dynamic Model of Autonomy Development (Borges, 2022) guided this four-year longitudinal study conducted at a university in Northern Brazil. This multiple case study utilized learning narratives, diaries, and a final interview to generate data. Learning narratives depicted the participants’ profile and their learning initial conditions, while diaries captured their reflections on language learning and autonomy. An interview was conducted in the final semester to shed light on how autonomy influenced students’ empowerment and participation in the academic and professional community (Borges, 2019; Murray, 2017; Nicolaides, 2017; Oxford, 2003). The results show that the personalized and complex nature of autonomy development is manifested differently for each student in varying contexts over time. Subsystems like motivation, beliefs, identities, and emotions were found to either enhance or inhibit autonomy along their language learning journeys.

Keywords: autonomization, language learning, trajectory, complexity paradigm

Learner autonomy is a complex process closely intertwined with various subsystems, including motivation, beliefs, identities, emotions, teachers, peers, language advisors, and context, among others. To fully grasp the complexity of autonomy, it is essential to consider the intricate relationships between these multiple aspects, which can either foster or hinder autonomy, leading to moments of dynamism and dynamic stability in its development. In this perspective, this article aims to shed light on the intricate nature of autonomy by using the Complex Dynamic Model of Autonomy Development (Borges, 2022) to examine the learning experiences of two undergraduate students majoring in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL). Over the course of their four-year undergraduate journey, a longitudinal multiple-case was carried out to answer the following question: How does the autonomization unfold in the trajectory of additional language learning for students majoring in TEFL?

The Complex Dynamic Model of Autonomy Development (CDMA)

In this study, autonomy is examined through the lens of complexity, drawing on the work of Borges (2019, 2022), and Paiva (2006; 2011a). Complexity theory provides a suitable framework for understanding learner autonomy as it highlights dynamism and interconectedness (Larsen-Freeman, 2017). From this perspective, autonomy can be defined as a complex, dynamic, and fluctuating process in which a definitive endpoint cannot be delimited because it is experienced by the learner in a non-linear and continuous manner throughout life, with moments of advances, stability, and setbacks, involving the interaction among a large number of processes, elements, agents, and other nested subsystems (Borges, 2022).

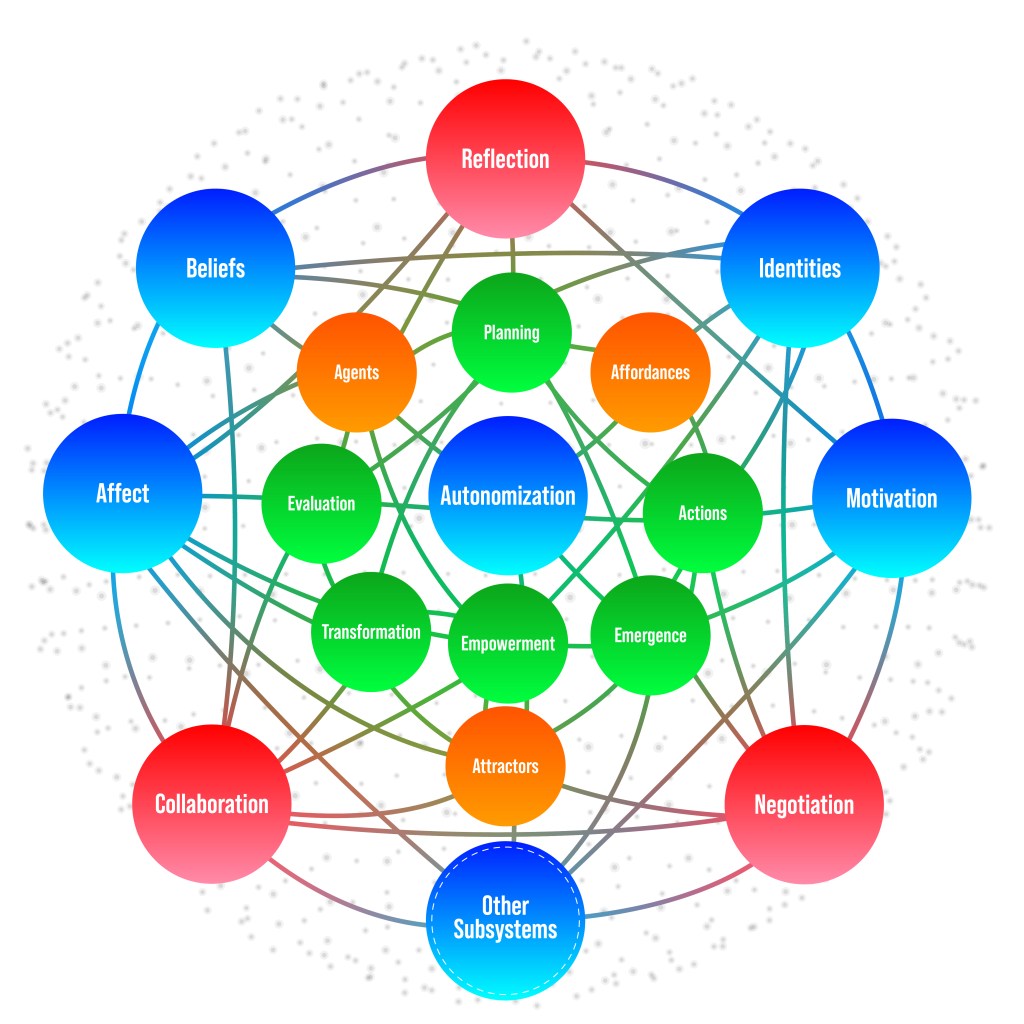

In my doctoral research, the Complex Dynamic Model of Autonomy Development (CDMA) was introduced as a comprehensive framework that encompasses manifold components influencing the development of autonomy over time, both as facilitators and inhibitors of this process (see Figure 1). These components encompass:

- Reflection, a supradimension in autonomy development, along with the fundamental processes supporting it, such as collaboration and negotiation (illustrated in red).

- The non-linear aspects typical of autonomy, including planning, actions, emergence, empowerment, transformation, and evaluation (illustrated in green).

- Subsystems that exert influence on autonomy, and vice versa, such as motivation, beliefs, identities, emotions, among others (illustrated in blue).

- The context, a dynamic and active component where all interactions take place, represented by the dotted outline in gray that permeate the interactions in the model.

- Contextual factors, encompassing various agents with whom learners interact, the affordances that students interpret and utilize within their learning environments, and attractors or attractor states, which represent preferred behavior patterns within the autonomy trajectory (illustrated in orange).

The CDMA offers a holistic perspective on the multifaceted nature of autonomy in the learning process. It illustrates autonomy as an emergent phenomenon that arises from the complex and dynamic network of interactions among its various components. Throughout the trajectory of this system, certain interacions become more evident and significant than others, underscoring the central role of interactions in the CDMA[1]. For a comprehensive understanding of the theoretical underpinnings of the model in English, refer to Borges (2022). Figure 1, below, represents the model, whose version in motion can be accessed at the link: https://youtu.be/ZeSMJu95fi8

Figure 1

The Complex Dynamic Model of Autonomy Development (Borges, 2022)

The CDMA is proposed as a tool for reflecting upon, self-regulating, and managing autonomy in language learning. It directs attention to the numerous aspects that impact this process. Building upon the model, the aim of this study is to comprehend the participants’ autonomy trajectories, with a specific focus on identifying relationships that either facilitated or hindered the emergence of autonomous behaviors in language learning, as discussed in greater detail in the following sections.

Methodology

This longitudinal multiple-case study aimed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the process of autonomization in language learning among two undergraduates majoring in TEFL. More specifically, its objective was to unveil the key elements and agents that have contributed to both dynamism and dynamic stability within the participants’ language learning systems. Furthermore, it sought to interpret the autonomization of each participant through the lens of the CDMA.

The research was conducted at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA) in Northern Brazil, where I am a professor in the Teaching English as a Foreign Language program. The participants in this study were four students who initially entered the program with a basic level of proficiency (A1 level). They were selected based on their learning narratives, which they developed during the “Learning to Learn Foreign Languages” course that I taught to incoming freshmen. For the purposes of this article, I will focus on discussing the trajectories of only two participants, Ester and Marília. A concise profile based on their learning narratives can be found in the Appendix.

Data were generated through learning diaries and a final interview, with the aim of encompassing the participants’ perceptions of their autonomization. These diaries were maintained throughout the first five semesters of the TEFL program, covering courses from English I to V. To observe the fluctuations in autonomy in their English learning journey, participants were asked to make three diary entries for each course. Additionally, due to a strike, an extra diary entry was requested to examine the impacts on their autonomy during that particular period. In this segment of the research, the dataset comprises a total of 32 diaries, supplemented by a semi-structured interview conducted with each participant immediately after the period of completion of TEFL program. These interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed. For this article, the instruments – narratives, diaries and the final interview – were translated from Brazilian Portuguese to English by the researcher.

For data analysis, I adopted a holistic approach, in which the texts were at first explored as a whole, and then analyzed based on emergent categories (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, & Zilber, 1998).

In addition, content analysis was employed to gain a deeper understanding of the narrated events, including the motivations, intentions, difficulties, and episodes of success in the participants’ journeys towards autonomization in the learning of additional languages, as will be discussed in the following section.

Findings

In this section, I explore each participant’s language learning journey within the first five semesters of the undergraduate TEFL course, using the complexity paradigm as a guiding framework. To gain insight into their experiences, I will use diary excerpts, emphasizing recurring themes, consistencies, and phase changes while considering influencing factors.

As mentioned in the methodology section, the three diary entries were written at the beginnig, middle and end of each semester of the five levels of the English language courses in the TEFL program. To better describe the main factors that affected the language learning trajectory of the participants, some excerpts were selected and discussed below.

Esther’s Learning Trajectory

At various points in her trajectory, Esther reported that her motivation influenced the level of investment she dedicated to autonomous English learning. This fact underscores that the motivational subsystem can contribute both to dynamize and stabilize the autonomization process. From the first semester of the course, the participant sought to interact with different elements and agents, generating dynamism in her learning, despite being influenced by factors inhibiting her autonomy, as illustrated below:

[1] Comparing with my first diary, I observe that I am more autonomous in my learning, but fluctuations in my motivation regarding the study of the foreign language have become my greatest difficulty. After receiving a “regular” grade on the English test, my enthusiasm for learning a new language declined to “zero”. To change this situation, I am intensifying my study hours and looking for new learning methods. Thus, I have reformulated my study schedule, trying to adapt my rest and learning hours. I use English books focused on basic grammar and use the CD player from the book. I am also participating in a project: language advising. This way, I can have an advisor to guide me on my progress in the four skills. I also participated in the “Ícone” project. In this project, the conversation was via Skype. A Portuguese Language student (in the USA) talked with an English Language student (in Brazil). This interaction with someone who was also learning a new language greatly encouraged me because I realized that anyone learning a new language faces difficulties. […] I believe that with these new attitudes, my motivation will definitely rise… (Esther, 1st semester, Diary 2)

In excerpt 1, Esther evaluated her attitude towards learning compared to the beginning of the semester, when she wrote her fisrt diary. She recognized that the fluctuation of her motivation affected her language learning. Although Esther’s motivation was negatively impacted by the low grade she received on the English test, the participant changed her attitude and decided to continue her efforts in the learning process. She invested in her own autonomization by reflecting, planning, and taking new actions that led to a change in phase state. Among the new patterns of behavior adopted, she began to interact with new agents such as the language advisor and native English speakers, as well as she began to reorganize her study schedule. Her interaction with foreign students of Portuguese in the “Ícone” project also led her to a new understanding of the difficulties inherent in language learning, demonstrating her ability to reflect on her own learning. The fact that Esther sought to expose herself to language use situations in direct interaction with native speakers from the very first semester, despite recognizing her limitations in speaking, demonstrates her efforts to achieve her goals and integrate into the academic context, exercising her autonomy.

In her trajectory, the influence of the belief that she should achieve perfect English pronunciation, like that of a native speaker, was noticeable. This belief affected Esther’s learning system, influencing the choice of strategies to be used:

[2] As a beginner in learning the English language, I have numerous difficulties, but the main one would be pronunciation. When I speak a sentence or some words, the impression I have is that there is something wrong with my pronunciation, and this situation makes me demotivated. […] Although my performance in speaking has improved, I still have the opinion that I should and can improve my pronunciation. Especially since this semester, in which the English Phonetics and Phonology class requires perfect intonation. (Esther, 2nd semester, Diary 5)

Excerpt 2 highlights the priority set by the participant, namely, the focus on “perfect” pronunciation of the language. Esther mentioned in several diaries the various actions she undertook to achieve this goal. The strong influence of the belief that she needed to learn pronunciation like a native speaker led Esther to adopt strategies that proved to be less effective for the development of her oral production, affecting her motivation (excerpt 2).

The next excerpt demonstrates that Esther’s autonomy was driven by the vision of her “future self” (Dörnyei, 2005, 2009) as a fluent English speaker. Motivated by this goal, she began to take advantage of new affordances available in her context (Van Lier, 2004, 2008). However, as the system is open and subject to the continuous self-organization of its components (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008), by the end of the second semester, the participant pointed out a series of factors that negatively influenced her learning:

[3] At the beginning of the semester, my autonomy was higher due to my determination to learn English as quickly as possible. So, I started attending the sit-in with the native speakers and searching for new learning strategies. However, with the arrival of a new teacher and personal problems, that determination got lost. […] As I was used to a more dynamic methodology from another teacher, this drastic change affected my learning. As the classes progressed, I realized that my performance in that subject was below what I would like. Many topics he taught, I simply couldn’t assimilate or practice. I tried to solve the problem by intensifying my studies, but with two consecutive losses in the family, my autonomy and motivation dropped to zero. (Esther, 2nd semester, Diary 6)

The new difficulties reported show that the influence of personal problems related to the classroom environment, such as incompatibility with the new teacher’s method, as well as emotional factors external to the classroom environment, such as the loss of loved ones, led Esther’s learning system to a state of entropy (Bushev, 1994), where the constant loss of energy affected her autonomy and motivation, leading to a pattern of dynamic stability.

Next, despite the university strike, collaboration and negotiation with the language advisor contributed to compensating for the loss of energy in Esther’s system, restoring her motivation to learn English:

[4] I talked to my advisor about these difficulties, and together we created a study plan. First of all, I made a list of my biggest difficulties in the English language, such as pronunciation and writing some words. Then we made a plan. […] With the Duolingo app, I practice English daily, as well as watch subtitled series and movies, and the study plan helps me improve my four English language skills. I hope that with these actions, I can really find the best mechanisms for my learning. (Esther, Strike, Diary 7)

At this point, the interaction with the language advisor created synergy in her learning system. Negotiating with this agent helped her move from the attractor state of dynamic stability in which she found herself, where she emphasized pronunciation practice due to the influence of her belief subsystem. Her new choices and actions fostered her English language learning, expanding her range of strategies for practicing the four skills.

However, upon returning to classes in the third semester, with the excuse of a lack of time due to academic demands, Esther stopped following the daily plan negotiated with her advisor, and stated to study English only on weekends. Furthermore, she again felt incompatible with the methodology adopted by the English III teacher. However, as the system is unpredictable, frustration with the monotony of English classes ultimately led to the emergence of new behaviors in her autonomy trajectory.

[5] Faced with a complicated situation at college, the only alternative I found was to seek more autonomy. I tried to be as self-taught as possible. I started reading more texts in English, like blogs, news, or even celebrity gossip news, all in English, even going through some words I didn’t know, I learned new terms and some slang I didn’t know in English. With a classmate’s recommendation, I created a profile on a site for conversation between people from various countries […] The frustration and discouragement I felt from the English class ended up boosting my learning. Despite being disheartening, it was a lesson that you always need to seek autonomy to achieve your goals, which is learning a new language. (Esther, 3rd semester, Diary 10)

In excerpt 5, Esther emphasized the need to assume autonomous behaviors, both in favorable learning contexts and in contexts considered unfavorable. This thought demonstrates her ability to self-organize and adapt to the difficulties faced, so that the learning system maintains its dynamism.

In the fourth semester, however, Esther still felt that her English level fell short of her expectations. At this point, the influence of emotional factors limiting or even paralyzing her actions came back to the surface. In a deep attractor basin, she reflected on her limitations, but she couldn’t act to overcome them. Attractor basins may be described as preferred states of the system in which a huge amount of energy is needed to move it from deep stability.

[6] Since the challenge is enormous, I have to look for alternatives that can relieve this pressure and strengthen my confidence, and consequently, my motivation. Thinking about this future is causing me great distress, and it directly affects my learning. I am participating in the advising project, even though I haven’t spoken to my advisor for a few weeks; I told her about these anxieties in our last meeting […]. Her advice was on point at the time, and I am trying to focus more on the present. (Esther, 4th semester, Diary 11)

[7] This disorganization of my time is directly affecting my academic performance because with a lack of time to study, I feel that I am regressing in my learning. In college, the consequences are the worst possible[…] I feel that my English is falling short once again, and I am afraid I won’t be able to reverse this situation. (Esther, 4th semester, Diary 12)

[8] I realized that I also had emotional problems related to college because I felt sadness about my performance in other subjects, not only in English IV. That’s why I decided to go to a psychologist to report these emotional problems, and I am calmer now because I can see that I will overcome these problems and that it all depends on me. So, I can’t be weak and give up everything during a moment of stress, anxiety. (Esther, 4th semester, Diary 13)

Excerpts 6, 7, and 8 highlighted the impact of emotions such as distress, fear, insecurity, anxiety, and sadness on Esther’s autonomization. At this point, the participant even reports feeling stagnant and regressive in her learning, as mentioned by Borges (2019). Esther sought the collaboration of her language advisor and even professional help to share her anxiety about her “feared self” (Dörnyei, 2005), i.e., the fear of not becoming fluent in English and not achieving her goal of becoming a teacher. The collaboration of these agents contributed in some way to regulate Esther’s emotions, but it did not generate sufficient changes in her attitudes for a phase state change.

When looking at learning in its complexity, there is evidence on how emotions have the power to shape what students do and how they learn (Barcelos, 2015). In Esther’s case, the emotional issues affecting her mental well-being may have contributed to her maintenance in an attractor basin, inhibiting or even blocking her ability to react to the difficulties she faced. At this moment of stagnation, Esther even abandoned frequent contact with her language advisor (excerpt 6), an agent that had previously contributed to her learning and autonomization.

In the fifth semester, in English V, Esther still felt very insecure about her ability to produce oral and written output in the target language. Demotivated by not achieving the level of fluency she aspired to and suffering from the impact of previously mentioned emotional issues, she chose to take a leave of absence from the TEFL program.

Marília’s Learning Journey

Marília’s learning journey is marked by insecurity due to her lack of proficiency in English. However, her resilience is also evident because despite the difficulties and personal problems she experienced throughout the course, she sought to maintain dynamism in her learning system, confirming her ability to adapt and overcome. Throughout her journals, it was noticed that reflection, as emphasized in CDMA, was a constant part of Marília’s journey:

[9] With the theories in the classroom, I realized that I need to take responsibility for my language learning, that I shouldn’t rely solely on the teacher, and that my difficulties can be overcome, including my insecurity. […] The fact that my classmates already speak in English has motivated me to study more because I need to dedicate myself more to language learning to be as proficient as them (Marília, 1st semester, Diary 1).

In the first semester of the TEFL program, students take a course called “Learning to Learn Foreign Languages” in which they study about autonomy, learning styles and strategies, motivation, affect, among other theoretical issues. Reflection should drive action, leading the learner to “choose future investments and decide efforts directed towards their own learning” (Bambirra, 2014, p. 106). Grounded in the theories studied in her undergraduate program, the participant demonstrated an understanding of her central role in guiding her own learning and overcoming difficulties, such as regulating her emotions.

The unpredictability and complexity of the language learning system were also evident at various points in this investigation. The fact that her classmates were already proficient, which could have discouraged the participant, had the opposite effect, motivating her to invest in new actions for her learning. The motivation subsystem, therefore, proved to be closely linked to autonomy, as she mentioned that her vision of a “future self” as a proficient English speaker favored greater dedication to language study (Dörnyei, 2005, 2009). The participant’s initiative to enroll in the language advising project in the first semester also represented an autonomous behavior:

[10] Speaking was my main difficulty in English because I used to be terrified and ashamed to speak in public, but gradually, this barrier has been overcome. My participation in the advising project has been of utmost importance in helping me overcome my English difficulties because through advising sessions, I understood that to learn a foreign language, I need to communicate in the target language. (Marília, 1st semester, Diary 3)

Just as with Esther, the interaction with the language advisor generated synergy in Marília’s autonomy at various moments, leading her to new affordances (Van Lier, 2004, 2008):

[11] This semester, I have been participating in American labs that help me work on my listening and speaking skills […]. I participated in the “Ícone” project, where I could speak in English with native Americans via Skype. This project encouraged me in learning English because it was essential for me to know that I was being understood when speaking with them and that I could understand them as well. (Marília, 2nd semester, Diary 4)

[12] Currently, I am participating in the PROPAZ project, where I work with underprivileged children so that they can develop an interest in learning English. This project has been very important for my English learning because I plan lessons and have the opportunity to practice in a classroom setting even before I graduate. (Marília, 2nd semester, Diary 5)

Excerpts 11 and 12 illustrated Marília’s level of awareness in adopting favorable strategies to overcome difficulties in her oral production. Since the system is sensitive to feedback (Larsen-Freeman, 1997), the experience of success in interacting with native speakers fueled Marília’s motivation. Excerpt 12 also described Marília’s participation as a volunteer in an extension project, highlighting her autonomy and the emergence of her identity as a teacher to be. This attitude reinforces the idea that language learning is an investment in continuous identity construction (Aragão, 2014).

When the strike began, Marília was kept away from her university activities and daily contact with the target language. In addition, she discovered an unexpected pregnancy with twins. These two events had unpredictable consequences, illustrating the butterfly effect (Larsen-Freeman, 1997; Paiva, 2011b). According to the participant, “these events, despite initially weighing against my learning, ended up positively propelling me” (Marília, Strike).

Upon returning to classes, the interaction of a series of factors negatively influenced her autonomization, including incompatibility with the English teacher’s methodology, the fact that her advisor left the city, and a lack of time to study due to the birth of her twins, leading her into an attractor basin (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008):

[13] The difficulties I reported remain the same, in which there was no progress. I even believe there was a certain regression in my language learning because I feel that I no longer speak English as I did before. This semester was full of doubts that made me question even what I had learned in previous semesters, leading me to think that I know nothing about English. (Marília, 4th semester, Diary 13)

[14] Lack of time has also been a difficult factor to overcome because I can’t organize my time to study, especially now that the babies require much more of my attention. […] My main difficulty continues to be speaking, and I also think I have emotional issues related to the language because I feel very insecure, now more than ever, about speaking in the target language and even somewhat pressured to do so. (Marília, 5th semester, Diary 14)

The significant impact of emotional factors such as insecurity, pressure, and fear of not achieving her goals, as envisioned in her “future self” (Dörnyei, 2005), contributed to a state of entropy. In a deep attractor basin, Marília not only felt a sense of stagnation in her English learning but also a loss of everything she had previously achieved (excerpt 13). This feeling of regression was also reported by Esther in her diaries (excerpt 7).

However, in the fifth semester, with the collaboration of new agents, the participant finally managed to move from the attractor basin she was in:

[15] Advising has been very important in my learning because it supports me in gaining autonomy and has also helped me see my own progress in the language that I cannot perceive on my own. With the help of my advisor, I have used strategies to overcome my English difficulties […]. I have felt more confident in responding to questions when asked in English. (Marília, 5th semester, Diary 15)

[16] The teacher has also significantly contributed to my learning process because she has helped me a lot with tips to improve my skills and has fostered my motivation to study. She always pointed out our progress in the language and maintained a pleasant classroom environment conducive to learning, along with her wonderful teaching style. (Marília, 5th semester, Diary 16)

The collaboration and negotiation with the Engligh V teacher and the new language advisor led to the emergence of new autonomous behaviors in Marília, akin to an “aha moment” in her journey (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008). She could self-regulate her emotions, regain her motivation, self-confidence, and perceive advancements in her English learning.

Engaging in self-evaluation, invoking another movement in autonomization described in CDMA, the learner narrated her achievements:

[17] Considering my difficulties reported in the recent diaries, I believe there has been significant progress in my English learning, especially in speaking, as it was heavily worked on in the last semester during advising sessions. […] At the moment, I do not have a defined difficulty because with the help of my advisor, we have created strategies to improve my other reported difficulties as well, such as writing, which I have been practicing by writing weekly diaries about events in my academic life. (Marília, 5th semester, Diary 16)

In the following excerpt, Marília narrates an experience of empowerment in her process of autonomy as a teacher to be:

[18] The challenge of creating lesson plans and delivering two lessons in English was initially daunting for me […]. It was a tough task, but it was also a triumph. I feel very happy to have been able to teach the entire class in English, to overcome my shyness in public speaking, and to do my best. This was certainly my greatest challenge this semester, which I managed to overcome with study, practice, and, most importantly, with the support of everyone rooting for my success. (Marília, 5th semester, Diary 16)

With the exercise of her autonomy and the collaboration of significant agents in her system, Marília managed to overcome the challenge of teaching classes in English. It is worth highlighting the participant’s emotional regulation and the emergence of positive emotions such as happiness and fulfillment. Thus, we observe the emergence of new autonomous behaviors and empowerment in using English as both a student and a teacher to be.

Emerging Aspects in the Autonomy Journey

In this section, I seek to interpret the autonomization of each participant based on the CDMA, considering the dynamism and fluctuations that characterized their trajectories.

Esther’s Autonomization

Esther was the first in her family to attend university. She had high self-expectations to become a proficient English speaker and a successful teacher. Her autonomy trajectory was significantly influenced by the affective, belief, and motivation subsystems, leading to fluctuating autonomy levels.

Initially, she actively engaged with various agents and opportunities, seeking collaboration with teachers, classmates, and her language advisor. She managed to transition from planning to action at times, but in other instances, she remained in attractor states, employing less effective learning strategies. Her autonomization showed a downward oscillation with moments of dynamic stability, marked by deep attractor basins causing learning system entropy.

Affect played a crucial role in her trajectory, ultimately leading to her college dropout after the fifth semester. A year later, her unsuccessful attempt to resume her studies in the 6th semester was revealed during her final interview.

[19] There were problems that affected me a lot, first because of my low self-esteem. […] Since I was a child, I have had a problem proving to people that I am the best and that I can do it. I entered the English course at university knowing almost nothing, and I made it. I think all of this weighed heavily, you know, because I was the first person in my family to go to college, so I wasn’t strong enough to continue. I even tried to continue in the 6th semester this year, but I already arrived feeling nauseous, very anxious, and especially with Marília not by my side anymore. […] When I saw those people with perfect English, and I saw almost no one at my level, you know, and I got very sad, so I couldn’t go anymore, I’m not going to college anymore. So, my personal reasons really weighed heavily, they were crucial for giving up, but I love English, I like it a lot, I practice every day, I try to say something, at least talking to myself. (Interview, Esther)

In excerpt 19, we witnessed the tumultuous emotions Esther faced upon her return to university: low self-esteem, immense self-imposed pressure, fear of giving up, loneliness, and a lack of support from her friend Marília in the new class. Aragão and Cajazeira (2017) note that reflection helps us become aware of our beliefs and emotions, allowing us to consciously accept or reject them. Unfortunately, suffering from emotional issues, Esther tried to reflect on her emotions, however, this was not enough to transform them positively, leading to her ultimate abandonment of the program.

The inability to properly reflect or address one’s emotions can immobilize the learner, sometimes causing the system to stagnate or even collapse (Borges, 2019). Esther’s learning system underwent a critical phase shift or bifurcation (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008). However, English remained a significant part of her life (excerpt 19). Fortunatelly, a year later, Esther enrolled in a bachelor’s program in Trilingual Executive Secretariat at a state public university, where she resumed learning languages, including English, Spanish, and Mandarin, which she chose as an optional language. She graduated this new course successfully.

Marília’s Autonomization

Marília’s journey towards autonomy proved to be oscillating but ascending. She went through various situations that threatened her continuation in the course, such as emotional issues, an unexpected twin pregnancy, and the consequent reduction in time dedicated to studying English. Despite the influence of these factors, that sometimes inhibited her autonomy, Marília managed to self-organize and change phase, assuming autonomous behaviors. This fact highlighted her adaptability and resilience (Masten et al., 2011).

Reflection, a supradimension in the CDMA, was a constant in Marília’s journey, contributing to her planning and acting upon a wide range of affordances for learning English. However, at times, under the influence of attractors, her reflections did not translate into actions.

In excerpt 20, the participant reports the contribution of the “Learning to Learn Foreign Languages” course at the beginning of the program:

[20] I could identify the difficulties I might face in the program, especially related to my motivation, which I think was quite challenging to deal with throughout the entire process until the end of the course. So, I learned that it was a phenomenon that changed over time, that alternated all the time, and also about autonomy, which was something I really wanted. Some people told me that I was very autonomous, but I couldn’t see that, and the course helped me try to achieve my motivation and autonomy […]. Yes, one of the things I learned is that we have to protect motivation, and I tried to do that, but as it is something very complex, I could only do it for a while, and then I couldn’t do it anymore […], autonomy and motivation were something that complemented each other, so it was something I tried to do all the time. (Interview, Marília)

Complex systems such as autonomy are sensitive to initial conditions, which means that small alterations at the beginning or at later stages along its trajectory can cause major future outcomes (Larsen-Freeman; Cameron, 2008). The excerpt 20 reveals the course mentioned positively contributed to the establishment of the initial conditions of Marília’s journey in the academic context.The appropriation of the autonomy theories contributed to a more mature reflection about her active role in learning English and to raising her awareness about the mutual influence of motivation and autonomy over time, as illustrated by the CDMA. Marília explicitly described how she made efforts to “protect” her motivation (Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2011, p. 66) and exercise her autonomy, recognizing the interdependence between these subsystems.

Affective factors and the multiple identities of being a mother, wife, student, and pre-service teacher also impacted Marília’s autonomy and motivation. Negotiating with her advisor and collaborating with teachers and peers generated synergy and contributed to the regulation of her emotions, leading to changes in phase states, where new behaviors emerged, such as the recovery of her self-confidence.

The participant’s vision of her “ideal self” as a legitimate English speaker and a successful future teacher motivated her and stimulated her participation in teaching, research, and extension projects, demonstrating her empowerment (Shrader, 2003) and the exercise of her autonomy, as emphasized in the following excerpt:

[21] I really want to be a teacher, which is a dream that has been with me for a long time. I know that I have a lot to learn, a long way to go to truly succeed in this career. […] Because for me, I don’t want to be just any teacher; I want to be something different, something that stands out for my students. I want them to have a broader perspective or achieve something, travel to another place, or even achieve proficiency in the language. Sometimes I even think that I want to be a teacher with a complex view because, as I went through all of this, I have experience in language learning, the difficulties, the achievements, I believe my perspective on the students has to be different. I believe I will be able to tread this path to become a good professional (Interview, Marília).

According to the CDMA, the identity system and autonomy influence each other. Excerpt 21 revealed Marília’s “possible selves” (Dörnyei, 2005, 2009; Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2011), expressed by her expectation of becoming a successful teacher in her “ideal self”, and by her fear of not being able to achieve this goal. She also expressed her desire to become a teacher with a “complex view”, indicating her intention to transform the theories that guided her experiences into future actions in the English teaching context.

While writing her undergraduate thesis, the participant chose to portray the fluctuation of her own motivation throughout the TEFL program, analyzing her own learning diaries. In the public defense conducted in English, she received an excellent grade, a significant achievement for her empowerment as a fluent English speaker, as described in her interview. After graduating, Marília was selected for a continuing education program for English teachers sponsored by the American Embassy in Brazil and began teaching English for kids. Her autonomy journey continued in new contexts.

Final Considerations

The CDMA has proven to be productive for interpreting the participants’ trajectories of autonomization, which unfolded in diverse ways across different scales of time and space. This highlights the complex, multidimensional, and emergent nature of autonomy developed throughout life (Freire, 2006; Paiva, 2006; Benson, 2013; Tatzl, 2016). The unpredictable way in which the various system components combined in interactions over time, as well as the personal choices and actions undertaken by the participants, underscored the personalized nature of autonomy development.

Reflection, a supradimension in the CDMA, was more constant in Marília’s trajectory and led her to make conscious choices regarding her own learning and to maintain dynamism in her autonomy. By exercising their autonomy, the participants benefited from collaboration and negotiation with agents such as teachers, advisors, and peers, as supports for autonomy development. However, it was observed that seeking collaboration alone, without the support of critical reflection and new actions in favor of autonomy, did not generate significant changes at certain moments in Esther and Marília’s trajectories.

The reciprocal influence between motivation and autonomy was evident in the participants’ trajectories, corroborating what other authors assert (Benson, 2006; Borges & Magno e Silva, 2008; Dörnyei & Ottó, 1998; Ushioda, 2009). In some situations, visions of the “ideal self” stimulated the protection of their motivation and investment in autonomy, while in others, demotivation contributed to the loss of energy in the system and dynamic stability of autonomy. Furthermore, the experiences in their language learning trajectories potentiated the emergence of identities (Aragão, 2014; Borges & Castro, 2022; Paiva, 2011a).

The dynamic, adaptive, and emergent nature of beliefs (Bambirra, 2014; Barcelos, 2015; Kalaja & Barcelos, 2015) in the participants’ experiences was also observed, along with their impact on the autonomization. In Esther’s case, the belief in the need of perfect English pronunciation contributed to the dynamic stability of her system at certain points. In other cases, as their beliefs were redefined, the participants transitioned to different phase states in which autonomous behaviors emerged. For instance, at first, Marília had believed she was not ready to speak English in public since she was afraid and ashemed of making mistakes. This belief problably prevented her to take advantage of some affordances to practice her oral skills. Then, with the help of advising sessions, she changed this beleif and understood that she needed to communicate in order to learn a target language (excerpt 10).

The strong influence of emotional factors in the autonomization of both participants was also highlighted (Aragão, 2008, 2011; Aragão & Cajazeira, 2017). Personal problems, family losses, as well as feelings of insecurity, anxiety, and fear demonstrated the potential to generate entropy and maintain the autonomization system in dynamic stability.

Therefore, the autonomy development trajectory unfolded in an unpredictable and personalized way, based on experiences in different contexts and continues to evolve throughout one’s life (Borges, 2019). In this process, the central role of interactions in autonomization is emphasized, as illustrated by the CDMA. The model corroborates that it is not the quantity but the quality of interactions that can bring about significant changes in favor of autonomy in language learning.

Among the limitations of this research, I emphasize the small number of participants and the fact the data was translated from Brazilian Portuguese to English. However, the data generated longitudinally provided evidence of how autonomization occurred in a TEFL context, bringing implications for the field of language teacher education. In current research, I have prioritized the experiences of pre-service teachers, seeking to observe how autonomy development experiences are transformed by undergraduates as they transition from the learning process to the language teaching process.

Notes on the Contributor

Larissa Borges is an Associate Professor at the School of Modern Foreign Languages and the Graduate Program in Creativity and Innovation in Methodologies in Higher Education (PPGCIMES), at the Federal University of Pará, Brazil. She leads the research group CARE (Collaboration, Autonomy, Reflection and Empathy in Language Teaching) and the Language Teaching Laboratory (LAEL), both focused on language teacher education. Her research interests include autonomy, affect and wellbeing in language teacher education seen under the complexity paradigm.

Acknowledgments

My gratitude goes to the generosity of the participants in this research who shared their trajectories with me over four years. I hope that the reflections and choices in their trajectories lead to personal and professional fulfilment.

References

Aragão, R. (2008). Emoções e pesquisa narrativa: Transformando experiências de aprendizagem [Emotions and narrative research: Transforming learning experiences]. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, 8(2), 295–320. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-63982008000200003

Aragão, R. (2011). Beliefs and emotions in foreign language learning. System, 39, 302–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2011.07.003

Aragão, R. (2014). Reflexão, identidade e emoção na aprendizagem de inglês [Reflection, identity and emotions in English learning]. Contexturas, 2, 28–48.

Aragão, R., & Cajazeira, R. V. (2017). Emoções, crenças e identidades na formação de professores de inglês [Emotions, beliefs and identities in English teacher education]. Caminhos em Linguística Aplicada, 16(2), 109–133.

Bambirra, M. R. A. (2014). Desenvolvimento da autonomia por meio do gerenciamento da motivação [Autonomy development through motivation regulation]. In L. Miccoli (Ed.), Pesquisa experiencial em contextos de aprendizagem: Uma abordagem em evolução (pp. 101–140). Pontes Editores.

Barcelos, A. M. F. (2015). Unveiling the relationship between language learning beliefs, emotions, and identities. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 5(2), 301–325. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2015.5.2.6

Benson, P. (2006). Autonomy in language teaching and learning. Language Teaching, 40(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444806003958

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning (2nd ed.). Longman.

Benson, P. (2013). Learner autonomy. TESOL Quarterly, 134, 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.134

Borges, L. (2022). A dynamic model of autonomy development as a complex phenomenon. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 13(2), 200–223. https://doi.org/10.37237/130203

Borges, L. (2019). The autonomization process in the light of complexity paradigm: a study of the learning trajectories of TEFL undergraduate students. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Federal University of Pará, Brazil. http://repositorio.ufpa.br:8080/jspui/handle/2011/11219

Borges, L., & Castro, E. (2022). Autonomy, empathy and transformation in language teacher education: A qualitative study. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 13(2), 286–304. http://doi.org/10.37237/130207

Borges, L., & Magno e Silva, W. (2008). Motivação e autonomia para a formação de um novo aprendente e de um novo professor [Motivation and autonomy for the education of a new Learner and a new teacher]. In R. Assis (Ed.), Estudos da língua portuguesa e de todas as línguas que fazem a nossa (pp. 139–151). UNAMA.

Bushev, M. (1994). Synergetics: Chaos, order, self-organization. World Scientific.

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ottò, I. (1998). Motivation in action: A process model of L2 motivation. Working Papers in Applied Linguistics, 4, 43–69.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (Eds.). (2009). Motivation, language identity and the L2 self. Multilingual Matters.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (Eds.) (2011). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd Ed.). Longman.

Freire, P. (2006). Pedagogia da autonomia: Saberes necessários à prática educativa [Pedagogy

of autonomy: Necessary knowledge to education practices]. (34th Ed.). Paz e Terra.

Kalaja, P., Barcelos, A., Aro, M., & Ruohotie-Lyhty, M. (Eds.). (2015). Beliefs, agency and identity in foreign language learning and teaching. Palgrave Macmillan.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (1997). Chaos/complexity science and second language acquisition. Applied Linguistics, 18(2), 141–165. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/18.2.141

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2017). Complexity theory: The lessons continue. In L. Ortega & Z. H. Han (Eds.), Complexity theory and language development: In celebration of Diane Larsen-Freeman (pp. 11–50). John Benjamins Publishing.

Larsen-Freeman, D., & Cameron, L. (2008). Complex systems and applied linguistics. Oxford University Press.

Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., & Zilber, T. (1998). Narrative research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation. Sage Publications.

Masten, A. S., Cutuli, J. J., Herbers, J. E., & Reed, M. G. J. (2011). Resilience in development. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 117–131). Oxford University Press.

Murray, G. (2017). Autonomy in the time of complexity: Lessons from beyond the classroom. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 116–134. https://doi.org/10.37237/080205

Nicolaides, C. (2017). Agency and empowerment towards the pursuit of sociocultural autonomy in language learning. In C. Nicolaides & W. Magno e Silva (Eds.), Innovations and challenges in applied linguistics and learner autonomy (pp. 19–41). Pontes.

Oxford, R. (2003). Toward a more systematic model of L2 learner autonomy. In D. Palfreyman & R. C. Smith (Eds.), Learner autonomy across cultures: Language education perspectives (pp. 73–91). Palgrave Macmillan.

Paiva, V. (2006). Autonomia e complexidade [Autonomy and complexity]. Linguagem & Ensino, 9(1), 77–127. https://doi.org/10.15210/rle.v9i1.15628

Paiva, V. (2011a). Identity, motivation, and autonomy from the perspective of complex dynamical systems. In G. Murray, X. Gao, & T. Lamb (Eds.), Identity, motivation and autonomy in language learning (pp. 57–72). Multilingual Matters.

Paiva, V. (2011b). Caos, complexidade e aquisição de segunda língua [Chaos, complexity and second language acquisition]. In V. Paiva & M. Nascimento (Eds.), Sistemas Adaptativos Complexos: Lingua(gem) e Aprendizagem (pp. 187–203). Pontes.

Shrader, S. (2003). Learner empowerment: A perspective. The internet TESL journal, 9(11). http://iteslj.org/Articles/Shrader-Empowerment.html

Tatzl, D. (2016). A systemic view of learner autonomy. In C. Gkonou, D. Tatzl, & S. Mercer (Eds.), New directions in language learning psychology (pp. 39–54). Springer.

Ushioda, E. (2009). A person-in-context relational view of emergent motivation, self and identity. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 215–228). Multilingual Matters.

Ushioda, E. (2011). Motivating learners to speak as themselves. In G. Murray, X. Gao, & T. Lamb (Eds.), Identity, motivation and autonomy in language learning (pp. 11–24). Multilingual Matters.

Van Lier, L. (2004). The ecology and semiotics of language learning: A sociocultural perspective. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Van Lier, L. (2008). Agency in the classroom. In J. P. Lantolf & M. E. Poehner (Eds.), Sociocultural theory and the teaching of second languages (pp. 163–186). Equinox.

Appendix

Esther’s Profile

Since childhood, Esther had a curiosity to learn a language, especially because her home was located near a tourist spot where international cruise ships docked at a local market for fruits and delicacies, and she often saw tourists speaking other languages. Her first contact with English in public school was in the 5th grade, but her fascination with the language quickly waned due to the teacher’s attendance in school. In middle school, English became her least favorite subject due to the teaching style and the focus on text comprehension and the use of the verb ‘to be’. However, high school marked the beginning of a new phase. In the 1st year, the new English teacher was unlike any previous ones, enchanting her with his methodology that involved the use of music, igniting her passion for the language. However, in the 2nd and 3rd years, this teacher’s innovative classes changed due to not conforming to the school’s evaluative method, which demotivated her. While visiting a vocational fair, the TEFL program intrigued her the most. Since she had never enrolled in private English courses due to her family’s financial constraints, she felt insecure when she entered the program among peers who were already proficient, so she befriended those who were beginners like her. She considers herself dedicated and hopes to become a teacher who makes a difference in Brazilian education system.

Marília’s Profile

She fell in love with English from the first encounter in middle school. She aspired to become a teacher, but her initial expectations were thwarted because she couldn’t learn the language at school, where the emphasis was limited to teaching the verb ‘to be’ and vocabulary. She decided to seek more knowledge about the language, studying on her own and using English books from the school library. The language taught in the high school she attended was French, which didn’t pique her interest. Considering herself shy and insecure, she contemplated other majors when applying for college, but her love for English led her to choose TEFL. Upon entering the program, she was relieved to discover that she didn’t need to be proficient in English. She became interested in exploring different ways of learning English and testing what she was concurrently learning in the language courses where she had just been awarded a full scholarship. She aims to overcome barriers in her learning to become a competent professional in the field, making a difference in public education where she received her schooling.

[1] The CDMA is the culmination of my doctoral research, written in Brazilian Portuguese (Borges, 2019).