Atef AbuSa’aleek, Department of English, Majmaah University, Saudi Arabia. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4727-2455

Eyhab Yaghi, Department of English, Majmaah University, Saudi Arabia. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4462-6366

AbuSa’aleek, A., & Yaghi, E. (2024). An investigation into EFL learners’ electronic feedback practices during the Coronavirus pandemic: Support and challenges. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(1), 86–108. https://doi.org/10.37237/150107

Abstract

Previous research has suggested that e-feedback mechanisms are widely misunderstood, difficult to perform efficiently, and often need to fulfill expectations to affect student performance substantially (Carless & Boud, 2018). To better understand EFL learners’ e-feedback practices, this study aimed to provide a comprehensive picture of EFL learners’ e-feedback practices throughout the pandemic in the general preparatory year college at Majmaah University.

This paper employed a quantitative method. More specifically, this study reports student responses to the e-questionnaire, which investigated the impact of e-feedback on students’ academic performance and the challenges these EFL learners face typically caused by e-feedback practices. The findings suggest that the EFL students received considerable technical support from the university through Blackboard training sessions. Also, they had instructors’ support regarding immediate, timely, and detailed e-feedback on all tasks, quizzes, and tests via various electronic tools. The study revealed the most important factors affecting students’ performance, such as engaging in discussions, comprehending feedback, utilizing e-feedback, aligning e-feedback with learning goals, using the instructor’s expertise in delivering suitable feedback, and employing effective learning strategies. Furthermore, the data showed that the students have the following challenges: difficulties logging into the Blackboard platform regularly due to network issues, needing to be informed about the importance of e-feedback, and lack of motivation to use e-feedback.

Keywords: e-feedback, feedback challenges, instructors’ e-feedback

Distance learning has emerged as an unavoidable solution to specific challenges in education at the secondary and tertiary levels due to the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in early 2020 (Bao, 2020; Basilaia & Kvavadze, 2020). Bao reported that transitioning all university courses from physical to online delivery in just a few days significantly changed the educational system. Moreover, this change generally involved a wide-ranging redesign of the lesson plans, teaching tools such as online platforms, audio-visual content creators, and technical support teams. In the digital era of higher education, distance learning had been expected to become a common practice by 2025 (Arum & Stevens, 2020), but the pandemic speeded up the process.

Furthermore, scholars have highlighted the significant role of electronic feedback or e-feedback due to its effectiveness (Chang et al., 2017; Ene & Upton, 2018; Henderson et al., 2019; Saeed & Qunayeer, 2020). There has been a tendency for teachers to rely more and more on specific electronic tools in delivering e-feedback to English language learners, in particular, Blackboard LMS (Ai, 2017; Basabrin, 2019), Google Docs (Saeed & Qunayeer, 2020), Zoom (Bohinski & Mule, 2016; Lenkaitis, 2020); screencasts (Bakla, 2020; Tseng & Yeh, 2019), WhatsApp (Susanti & Tarmuji, 2016).

However, the impact of feedback on students’ performance is highly variable, widely misunderstood, and difficult to perform efficiently (Boud & Molloy, 2013; Carless & Boud, 2018; Evans, 2013; Hattie, 2009). While assessment feedback is one of the critical aspects of the learning process, dissatisfaction with the feedback of some instructors and learners remains a significant issue in higher education (Henderson et al., 2019). Previous studies (Boud & Molloy, 2013; Henderson et al., 2019; Huxham, 2007; Winstone et al., 2017) have reported different reasons behind students’ dissatisfaction with feedback, such as issues in content, timeliness, impact, and students’ unwillingness to use feedback. Huxham (2007) stresses the importance of feedback in enhancing learning outcomes. Feedback helps learners understand their performance, encourages self-assessment, directs improvement efforts, and boosts motivation and engagement. This study is conducted in response to the various challenging issues and concerns regarding EFL learners’ e-feedback practices . In addition, this research was conducted to fill the gaps identified in the latest studies regarding the need for further investigation on the supports and challenges of learners’ e-feedback practices in higher education and the impacts of feedback on students’ performance (Boud & Molloy, 2013; Carless & Boud, 2018; Henderson et al., 2019).

This suggests that students’’e-feedback practices need to be explored regarding their supportive and challenging role in learning. Therefore, the current study aimed to provide a comprehensive picture of EFL learners’ e-feedback practices in the preparatory year college at Majmaah University in Saudi Arabia by answering the following specific research questions:

RQ1: In what ways do the e-feedback practices support the EFL learners’ performance?

RQ2: What are the main challenging issues perceived by EFL learners emerging from e-feedback practices?

Literature Review

A Comprehensive Perspective of Feedback Literacy

Expanding upon previous definitions provided by Boud and Molloy (2013) and Carless (2015), feedback is a systematic procedure in which learners interpret information from many resources and employ it to improve their work or learning approaches. Feedback is a complex mechanism shaped by practice, individual variables, and contextual constraints (Henderson et al., 2019). E-feedback refers to feedback that is communicated with the help of a technological tool (Ene and Upton, 2014). Teacher e-feedback refers to written comments given by teachers on students’ written writings using asynchronous related to technology or software applications (AbuSa’aleek & Shariq, 2021; Ene & Upton, 2018; Saeed & Qunayeer, 2020).

Feedback can be categorized into two main types: global and local. Global feedback focuses on issues in students’ writing, such as content and ideas, organization, and coherence. In contrast, local feedback addresses specific issues, such as punctuation, vocabulary, and grammar, and assignment requirements, like APA citation and referencing (AbuSa’aleek & Alotaibi, 2022; Alharbi, 2020; Saeed & Qunayeer, 2020).

Feedback is an influential aspect that significantly impacts academic success. Nevertheless, the extent of its influence varies significantly, emphasizing the inherent difficulties in maximizing its advantages. Feedback mechanisms in higher education are frequently misinterpreted, which hinders their efficient implementation and desired influence on student performance (Boud & Molloy, 2013; Evans, 2013; Hattie, 2009). In their study, Henderson et al. (2019) identified three primary aspects that lead to challenges in providing feedback: contextual constraints and individual capacity, as noted by both learners’ and instructors’ feedback practices.

Developing skills in providing and utilizing feedback is essential for students to optimize its advantages and enhance their learning and academic achievements. According to Carless and Boud (2018), the students’ feedback literacy reflects their understanding, abilities, and disposition needed to make sense of comments and use them to improve their work and learning processes. Carless and Boud (2018) developed a framework of students’ features of feedback literacy to maximize the students’ potential to respond to feedback. This framework includes students’ appreciation of their role in feedback processes, which encompasses learners acknowledging the significance of feedback and comprehending their proactive involvement in its processes. Students must cultivate evaluative judgment, which refers to their ability to make discerning conclusions regarding the quality of their work and that of others, and managing effect, which refers to feelings, emotions, and attitudes toward feedback. Finally, taking action requires that learners act and actively engage in the feedback they have received.

Furthermore, researchers such as Winstone et al. (2017) highlight the significance of learners’ understanding of how to actively obtain, engage with, and implement feedback, which is sound now and in their future endeavors. When students receive substantial training, they become more efficient in improving their feedback literacy. On the other hand, Patton (2012) said expected gains are only possible with training and peer feedback support.

Opportunities and Challenges of E-feedback

Students respond to the feedback provided in many ways depending on the program, curriculum, and context they interact with, as well as their prior experiences and personal traits (Carless & Boud, 2018). However, when working online, one of the most critical aspects of how learners respond to feedback is the tone in which feedback is communicated (Lipnevich et al., 2016). Students’ responses to instructor feedback show how well they will spot errors, incorporate the corrective feedback, or react to it after they receive it (Alsolami & Elyas, 2016). Enabling the timely and easy exchange of feedback through various collaborative tools seems to be well-accepted and welcomed by students. Particularly, students appreciate audio feedback due to its personalized, dynamic, and engaging quality (Carless & Boud, 2018; Parkes & Fletcher, 2017).

Several previous studies have identified and highlighted the opportunities and challenges of e-feedback provided via various electronic tools. For example, Mahoney et al. (2019) reported that video feedback could foster a social interactional approach due to its affordances compared to written or audio feedback. In addition, it seems to be a viable alternative to conventional feedback for its relational richness and feedback transmission rather than dialogue. Technological tools could only make distance learning successful if the teaching staff were familiar with the technology themselves because this would lead to the success of e-learning (Hoq, 2020). Octaberlina and Muslimin (2020) suggested that training on how to use the LMS should be offered before the actual class. Gillett-Swan (2017) reported that many instructors faced challenges with distance education as they were required to have higher levels of technical competency and skills in addition to their daily academic duties, which affected students’ involvement and performance. On the other hand, screencast correction gives feedback to students in the form of a moving image, though it lacks facial expressions and body language. Although some may view this element of screencast correction as a drawback, it is crucial to acknowledge that the visual nature of the moving film still enables teachers to highlight corrections and offer comprehensive explanations (Borup et al., 2014; Mahoney et al., 2019).

Previous studies have effectively addressed feedback provided on both micro and macro issues via screencast (Bakla, 2020). Furthermore, Prior research (see Henderson and Phillips, 2015; Orlando, 2016; Thomas et al., 2017; West & Turner, 2016) has reported various advantages of screencasts, such as providing more detailed feedback (Thomas et al., 2017; West & Turner, 2016), shifting the focus from surface-level to substantive feedback (Henderson & Phillips, 2015), and providing natural conversational feedback (Orlando, 2016). On the other hand, for any educational effort, it is essential to consider students’ perspectives, especially regarding the barriers and concerns that may prevent them from receiving, recognizing, and applying feedback (Carless & Boud, 2018). For example, as some researchers and students have reported, screencasts have certain disadvantages, such as technical issues related to video size and slow downloads (Lamey, 2015), student anxiety before viewing their feedback (Ali, 2016; Mayhew, 2017), an (in)ability to identify feedback within tasks (Henderson & Phillips, 2015), as well as student preference for written feedback (Borup et al., 2015; Orlando, 2016). The study by Tseng and Yeh (2019) showed that most students preferred receiving written feedback because it is constructive, informative, and more explicit than video feedback. Further, Elola and Oskoz (2016) revealed that students preferred to receive written feedback on grammatical issues and video feedback on content issues. Furthermore, it was found that both Microsoft Word and screencast feedback had improved students’ writing skills.

Research (Tai et al. 2017) has highlighted the importance of students improving their evaluative judgment about the feedback processes and the quality of their work and their peers’ work. The acknowledgment of the evaluative nature of feedback is consistent with the broader realization that students actively participate in the feedback process.

Considerable studies have investigated the usefulness and preferences associated with various types of feedback. Borup et al. (2015) found that text feedback was more effective and structured, whereas video feedback promoted more conversational and supportive communication. In their research, Kostka and Maliborska (2016) stated that audio feedback was more convenient for second-language writing with an expanded explanation. Li and Akahori (2008) found that audio feedback enhances the social presence of the instructors.

However, only intermediate students benefited from audio feedback, which was ineffective for more advanced students. Notably, Audio and direct feedback comprised the most significant part of the feedback provided to the learners, which was also their favorite type of feedback (Nemec & Dintzner, 2016).

The feedback contained a mix of global and local feedback via video and text modes. Notably, the students strongly preferred screencast video feedback over text mode feedback due to its efficiency, clarity, and ease of use, as highlighted in studies by Cunningham (2019, 2017).

Nevertheless, in traditional feedback, due to the lack of opportunities for students to evaluate and discuss the feedback before revising their work, only very few of them can effectively act on it (Robinson et al., 2013). Critical feedback may have positive and negative effects on students’ learning, depending on factors such as motivation, self-efficacy, and the ability to constructively manage their emotions (Pitt & Norton, 2017). Through evaluation of feedback, imitation, engagement, and conversation, implicit awareness of feedback processes emerges (Bloxham & Campbell, 2010). If students do not see themselves as active learners rather than passive recipients of feedback, they cannot use corrective feedback effectively in revising their tasks (Boud & Molloy, 2013).

Research Method

Research Context and Participants

The research was conducted at the Preparatory Year Program (PYP), which focuses on developing English language skills to prepare students who wish to specialize in medical and computer colleges at Majmaah University, Saudi Arabia, at the end of the first semester of 2020-2021. Majmaah University provides distance education and online courses through the university learning management systemLMS to maintain learning and teaching practices and several other activities, such as online workshops and training sessions.

The study population consisted of 1,000 students of the PYP. The researchers divided the population into homogeneous groups according to their primary specialization and gender: students were grouped in General English 1, General English 2, English for Health Science, and English for Engineering. The EFL students had the same cultural background, nationality, religion, and educational system, came from the same geographical area, and their native language was Arabic. Their age ranged from 18 to 20, and this sample consisted of male and female students. The study sample included (N = 328) (PYP) students in the English language program. The researchers designed an electronic questionnaire. The participants were asked to enter the link sent to them by email and fill in the proposed questionnaire. The data was collected over two weeks. Each group took two days to complete the questionnaire and get the required responses. The researchers obtained a maximum number of participants to ensure adequate population representatives.

The sample size was calculated to decide the number of participants needed to determine the EFL learners’ e-feedback practices. The sample size was calculated based on the Cochran Formula for Sample Size Calculation: n=(n0/(1+((n0-1)/N)) at a 95% confidence level and 0.05 confidence interval. Where n0 is Cochran’s sample size recommendation equals 1.96 at the 95 % confidence level, N refers to the population size, and the lowercase n is the new sample size. Based on this equation, 385 / (1 + (384 / 1000)) = 278, the target sample size representing the population was (278) samples. Therefore, according to Sekaran (2006), if the study population is 1000, the sample size ratio is 278 respondents.

Concerning the participants’ consent statement, first, the students were requested to participate in a web-based online survey on learners’ e-feedback practices . Second, they were informed about the purpose of the questionnaire and that their participation in this study was voluntary. Third, they were informed that their information could be used for research and kept confidential.

Instruments, Data Collection and Analysis

The researchers employed a quantitative method since it sought answers from participants to provide a comprehensive picture of EFL learners’ e-feedback practices. Furthermore, this study aimed to investigate the impact of e-feedback on students’ academic performance and the challenges faced by EFL learners typically emerging from e-feedback practices using an e-questionnaire. The rationale behind quantitative design is that quantitative data and subsequent analysis can provide a diversified understanding of the problem under study. In addition, the quantitative method paves the way for progressively increasing the validity, reliability, and objectivity of the interpreted data, which helps present the collected data in an easily assignable way (Byrne, 2002).

The e-questionnaire had a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. The e-questionnaire consists of 34 statements distributed in six dimensions to explore EFL learners’ e-feedback practices during the Covid-19 pandemic, namely: (1) institutional supports and challenges in distance education; this dimension focuses on exploring training sessions on Blackboard, training materials, and the necessary technical support provided by the university. (2) network challenges, this dimension explores the obstacles to network connectivity that learners may have had during their online learning journey; (3) supports and challenges in the instructors’ e-feedback practices, which explores the facilitation and obstacles related to teachers’ utilization of e-feedback methods, encompassing the efficacy and accessibility of instructor feedback, (4) multimodality of e-feedback, which explores the various modalities of e-feedback, such as text-based, Audio, or video feedback, and via Blackboard Collaborative tools, WhatsApp, and email. (5) supports and challenges of the content of e-feedback, which focuses on the content of e-feedback, precisely local issues (grammar, vocabulary, punctuation) and global issues (content and the organization of the task) and (6) factors affecting students’ performance such as engaging in comprehension, discussions regarding the e-feedback received and achieving the desired learning outcomes.

36 students took part in a pilot study to check the questionnaire’s reliability by calculating Cronbach’s alpha estimation. The questionnaire demonstrated excellent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .91). The e-questionnaire was sent to the students involved in the study (N = 328) through WhatsApp groups.

The data from the questionnaire was analyzed with SPSS to get the descriptive statistics such as means and standard deviation. The means were divided into three cut-off scores used in previous studies (Budin, 2014; Ishtaiwa & Aburezeq, 2015; Jamrus & Razali, 2021; Sahin, 2014): strong (3.67–5), moderate (2.34–3.66), and low (1–2.33). The researchers used these cut-off scores for scale to determine and differentiate each questionnaire item’s status.

Findings and Discussion

Supports and Challenges of EFL Learners’ E-Feedback Practices

This section presents the findings from the quantitative analysis of the e-questionnaire. The findings of the two research questions are presented under the following six dimensions.

Institutional Support and Challenges in Distance Education

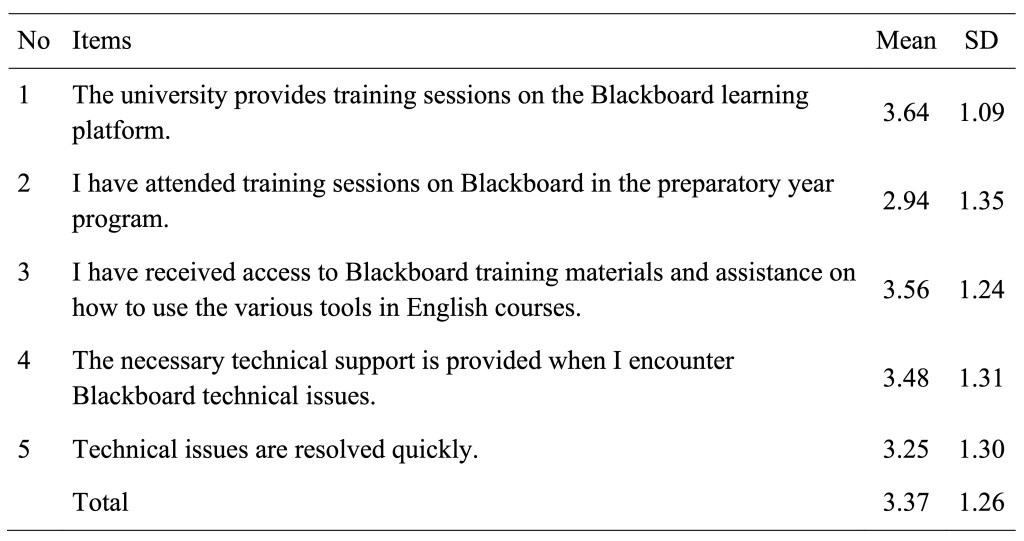

The students were asked to respond to five items to identify the institutional support and the resultant challenges regarding distance education. The mean and standard deviation in Table 1 illustrates that the overall mean of the student’s responses to the five items ranged from 2.94 to 3.64. This showed institutions’ support and challenges in distance education when distance learning was adopted fell in the moderate category (M=3.37, SD =1.26). In addition, these findings reflect the university’s provision of training sessions on the Blackboard learning platform (M = 3.64, SD = 1.09). The students received access to Blackboard training materials and were assisted in using the various tools to support their learning in English courses (M = 3.56, SD = 1.24). Other findings showed that the students received the necessary technical support from the technical support team (M = 3.48, SD = 1.31), and their technical issues were resolved quickly (M = 3.25, SD = 1.30). Finally, the students reported that they had attended training sessions on Blackboard in the preparatory year program during the COVID-19 pandemic (M = 2.94, SD = 1.35), and this item had the lowest mean.

Table 1

Descriptive Analysis of Institutional Support and Challenges

Network Challenges

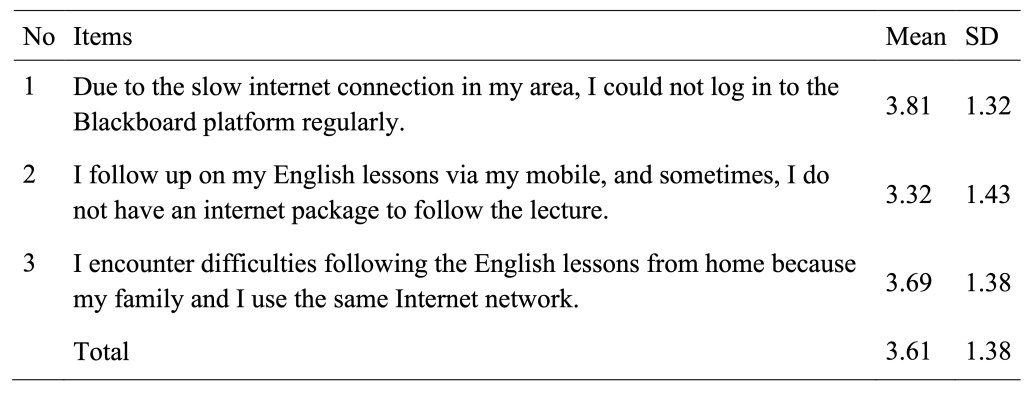

The students were asked to respond to three items to identify their challenges when attending their English classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. The students’ responses to each questionnaire item regarding issues with the network ranged from 3.32 to 3.81. This showed that the student’s problems with the network fell into the moderate to high categories. Table 2 shows that most students encountered difficulties logging into the Blackboard platform regularly due to internet connection issues in their local areas (M = 3.81, SD = 1.32). Furthermore, as the results reveal, the students encountered some difficulties with the internet connection since all the family members were using the same Internet network, making the connection much slower (M= 3.69, SD = 1.38). Finally, the findings indicated that a few students needed the Blackboard Application to connect and attend English lessons on their mobile phones (M = 3.32, SD = 1.43).

Table 2

Descriptive Analysis of Network Challenges

Supports and Challenges to in the Instructors’ E-Feedback Practices

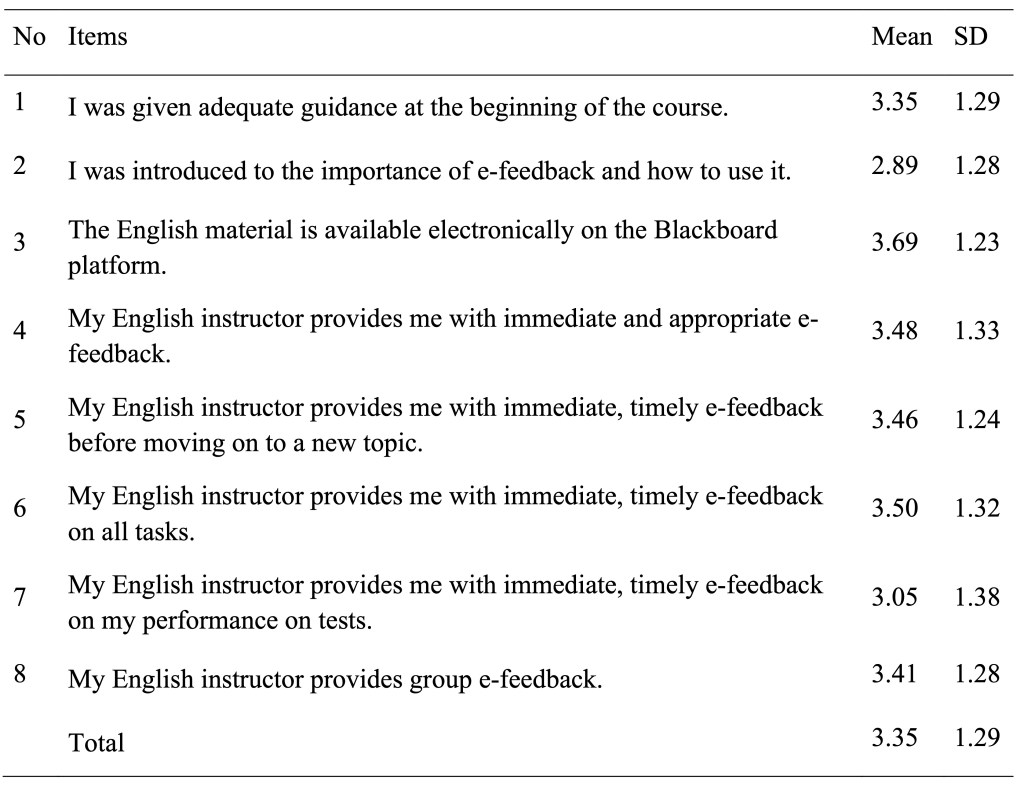

Based on the descriptive analysis of the eight items related to supports and challenges with e-feedback practices, as shown in Table 3, the overall mean of the students’ responses ranged from 2.89 to 3.69, falling into moderate to high categories. For example, one item in this section, “the English material is available electronically on the Blackboard platform,” was rated 3.69 (high category). In contrast, the rest of the items fell into a moderate category.

As the results show, most students reported that feedback was immediate and timely on all tasks (M = 3.50, SD = 1.32) and immediate and appropriate e-feedback in general (M = 3.48, SD = 1.33). The feedback was immediately and timely provided before moving on to a new topic (M = 3.46, SD = 1.24). Furthermore, the students reported that they received group e-feedback (M = 3.41, SD = 1.28), adequate guidance at the beginning of the course (M = 3.35, SD = 1.29), and immediate e-feedback on their performance in tests (M = 3.05, SD = 1.38). Finally, the findings indicated that fewer than half of the students needed to be introduced to the importance of e-feedback and how to use it (M= 2.89, SD = 1.28).

Table 3

Descriptive Analysis of Supports and Challenges in Instructors’ E-Feedback Practices

Multimodality of e-Feedback

E-feedback multimodality was investigated by asking the students to answer seven questionnaire items. The questionnaire aimed to identify the support and challenges of e-feedback the students encountered when taking their English classes. As shown in Table 4, the students’ responses ranged from 2.77 to 3.54 and fell in the moderate category. As the results revealed, the students reported that they received e-feedback the way they preferred (M = 3.21, SD = 1.26) via screencasts (video) e-feedback (M= 3.54, SD = 1.28), audio e-feedback (M = 3.08, SD = 1.29), and written e-feedback (M = 3.03, SD = 1.24). Furthermore, the students reported receiving written, audio, and screencast e-feedback mostly via Blackboard collaborative tools (M = 3.50, SD = 1.18) and WhatsApp (M = 3.33, SD = 1.27). Finally, the findings indicated that the students received less e-feedback via email (M = 2.77, SD = 1.29).

Table 4

Descriptive Analysis of Supports and Challenges of Multimodality of E-Feedback

In Table 5, it could be seen that the descriptive analysis of the four items related to supports and challenges of the content of e-feedback ranged from 3.00 to 3.37 and fell in the moderate category. As the results revealed, the students reported receiving e-feedback on global issues (M = 3.09, SD = 1.24) more than e-feedback on local issues (M = 3.00, SD = 1.21). Furthermore, ELLs reported receiving both local and global e-feedback for all tasks (M = 3.37, SD = 1.29) and detailed e-feedback for all the submitted quizzes and tests (M = 3.15, SD = 1.36).

Table 5

Descriptive Analysis of Supports and Challenges of the Content of E-Feedback

Factors Affecting Students’ Performance

The students responded to seven questionnaire items to identify the factors affecting their performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. The mean and standard deviation in Table 6 indicate that the overall mean for the seven questionnaire items ranged from 3.12 to 3.45, and all the items fell in the moderate category.

The findings indicated that the students reported that their instructors have sufficient experience providing appropriate feedback (M = 3.45, SD = 1.26). They also reported that the e-feedback helped them achieve course learning outcomes (M = 3.41, SD = 1.22), improved their performance (M = 3.36, SD = 1.30), and helped them employ the most effective learning strategies to learn English (M = 3.34, SD = 1.29). Furthermore, the students reported that they had the opportunity to discuss the e-feedback with their English instructors (M = 3.33, SD = 1.27). As a result, they understood the e-feedback and modified their tasks based on the feedback (M = 3.33, SD = 1.25). Finally, the findings indicated that some students found e-feedback annoying and did not take advantage of it (M = 3.12, SD = 1.21).

Table 6

Factors Affecting Students’ Performance

Concerning Blackboard training sessions, the students reported that they had been provided an opportunity to be trained, which helped them better understand how to use the various tools to support their learning. In addition, they received the necessary technical support, and their technical issues were quickly resolved. In the same vein, there was much debate as universities rapidly shifted toward online and hybrid teaching modes (Kirkwood & Price, 2014; Salmon, 2014). The current study’s results are consistent with previous studies (Gillett-Swan, 2017; Hoq, 2020; Octaberlina & Muslimin, 2020) that emphasize the significance of teaching staff’s expertise in technology for effective distance learning.

Regarding the impact of internet connection issues on e-feedback practices, the findings showed that most students encountered difficulties logging into Blackboard regularly. This finding aligns with previous studies (Fey et al., 2008; Octaberlina & Muslimin, 2020). The latter authors reported that students faced three challenges during their online learning: lack of e-learning experience, internet coverage problems, and physical conditions such as eyestrain. Fey et al. (2008) reported that access to online classes was considered a significant concern for all students, especially those who lived in rural areas.

Several noteworthy observations were made regarding the support and challenges regarding the instructors’ e-feedback practices. Firstly, the students reported that electronic material was available on Blackboard. Moreover, the students appreciated timely feedback on all tasks before moving on to a new topic. The students also appreciated receiving group e-feedback and adequate guidance at the beginning of the course. This finding is aligned with previous studies (Alsolami & Elyas, 2016; Carless & Boud, 2018; Parkes & Fletcher, 2017 ) that emphasize the feedback’s prompt and convenient communication and the personalized, interactive, and stimulating nature.

Concerning the multimodality delivered to the students, the students received feedback in various forms, such as screencasts (video), audio e-feedback, and written e-feedback, via various electronic tools. This finding is in line with previous research (Bakla, 2020; Borup et al., 2015; Elola & Oskoz, 2016; Harper et al., 2012; Orlando, 2016; Saeed & Qunayeer, 2020; Tseng & Yeh, 2019).

In terms of the support and challenges regarding the content of e-feedback, generally, the students reported that they received detailed e-feedback on global issues more than e-feedback on local issues in all tasks, quizzes, and tests. This finding aligns with previous research (Cavanaugh & Song, 2014; Saeed & Qunayeer, 2020), which indicated that tutors provided and focused their e-feedback more on global rather than local issues, as global issues appeared to generate more engagement.

Regarding factors affecting students’ performance, The findings revealed that English language instructors had sufficient experience in providing appropriate feedback regarding factors affecting students’ performance, which is consistent with previous studies (Boud & Molloy, 2013; Pitt & Norton, 2017; Octaberlina & Muslimin, 2020; Oraif & Elyas, 2021) that stressed the significance of learners actively engaging in the feedback process and critical feedback can yield both beneficial and detrimental outcomes, as well as the need for learners to recognize the most effective learning strategies and types in order to improve their performance.

Conclusion

This study contributes to previous research by identifying the different trends of e-feedback practices support and challenges encountered by English language learners when distance learning was adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic. These trends concern the support and challenges in distance education, network challenges, and support and challenges in the instructors’ e-feedback practices. Furthermore, this study provides insight into the impact of multimodal e-feedback, such as screencast (video) e-feedback, audio e-feedback, and written e-feedback via various electronic tools. Finally, this study presents significant findings, particularly the patterns of e-feedback content that the students received, as well as support and challenges affecting students’ performance during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study has shown that the EFL students instantly received considerable technical support and Blackboard training sessions. Also, they got instructors’ support regarding immediate and timely e-feedback practices. In addition, detailed e-feedback was provided more on global issues than local issues in all tasks, quizzes, and tests via various electronic tools. This study has identified the contributing factors affecting students’ performance during the Covid-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the findings sufficiently revealed the following challenges for the students: difficulties logging into Blackboard regularly due to network issues, not being explained the importance of e-feedback and how to employ it, and finding e-feedback annoying at times which prevented some students from making the most of it.

The findings have several practical implications for EFL teachers. Accordingly, the feedback practice is a collaborative process that requires the participation of all parties, whether students or instructors. Feedback is a dynamic mechanism shaped by students’ e-feedback literacy, instructors’ e-feedback practices, and the multimodality of delivering e-feedback and the patterns of e-feedback content. Therefore, EFL instructors should consider the significant factors affecting students’ performance when delivering e-feedback. For example, they should promote learner engagement in the feedback process by offering chances for self-reflection, peer feedback, and group correction. They should also acknowledge the possible influence of constructive criticism on learners’ drive and confidence, and aim for a balanced strategy that incorporates both constructive feedback and sound reinforcement.

Moreover, e.feedback fosters student empowerment by promoting their responsibility in learning by identifying efficient learning methods and adapting their individual learning preferences. Instructors should also endeavor to provide feedback swiftly, address students’ work, and offer direction for improvement promptly. There was a need to enhance students’ feedback literacy to improve the process of feedback provision for more successful academic achievements (Carless & Boud, 2018).

This study has several limitations that need to be considered. First, this research is based on a sample of 328 English language learners in the preparatory year program. Therefore, future research should include samples from graduate and postgraduate levels to verify or confirm the findings of this study. Second, this study is limited to quantitative analysis of the e-questionnaire regarding support and challenges concerning learners’ e-feedback practices. Thus, future studies should concentrate on quantitative and qualitative analysis of students’ actual performance and their uptake of e-feedback. Finally, feedback is a dynamic mechanism; thus, future studies should concentrate on students’ and instructors’ e-feedback literacy.

Notes on the Contributors

References

AbuSa’aleek, A., & Alotaibi, A. (2022). Distance Education: An investigation of tutors’ electronic feedback practices during coronavirus pandemic. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (IJET), 17(4), 251–267.

AbuSa’aleek, A. O., & Mohammad Shariq, M. (2021). Innovative Practices in Instructor E-feedback: A Case Study of E-feedback given in Three Linguistic Courses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Special Issue on Covid 19 Challenges (1) 18319–8. https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/covid.14

Ai, H. (2017). Providing graduated corrective feedback in an intelligent computer-assisted language learning environment. ReCALL, 29(3), 313–334. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095834401700012X

Ali, A. (2016). Effectiveness of using screencast feedback on EFL students’ writing and perception. English Language Teaching, 9(8), 106–121. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v9n8p106

Alsolami, E. H., & Elyas, T. (2016). Investigating teachers’ corrective feedback and learners’ uptake in the EFL classrooms. International Journal of Educational Investigations, 3(1), 115–132. http://www.ijeionline.com/attachments/article/50/IJEI.Vol.3.No.1.09.pdf

Arum, R., & Stevens, M. (2020). What is a college education in the time of Coronavirus? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/opinion/college-educationcoronavirus

Bakla, A. (2020). A mixed-methods study of feedback modes in EFL writing. Language Learning & Technology, 24(1), 107–128. https://doi.org/10125/44712

Bao, W. (2020). COVID-19 and online teaching in higher education: A case study of Peking University. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(2), 113–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.191

Bardine, B. A., Bardine, M. S., & Deegan, E. F. (2000). Beyond the red pen: Clarifying our role in the response process. The English Journal, 90(1), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.2307/821738

Basabrin, A. (2019). Exploring EFL instructors and students’ perceptions of written corrective feedback on blackboard platform: A case study. Arab World English Journal: Special Issue: Application of Global ELT Practices in Saudi Arabia September. 179–192. https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/elt1.13

Basilaia, G., & Kvavadze, D. (2020). Transition to online education in schools during a SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Georgia. Pedagogical Research, 5(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/7937

Bloxham, S., & Campbell, L. (2010). Generating dialogue in assessment feedback: Exploring the use of interactive cover sheets. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(3), 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602931003650045

Bohinski, C. A., & Mulé, N. (2016). Telecollaboration: Participation and negotiation of meaning in synchronous and asynchronous activities. MEXTESOL Journal, 40(3). https://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=1489

Borup, J., West, R. E., Thomas, R. A., & Graham, C. R. (2014). Examining the impact of video feedback on instructor social presence in blended courses. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(3), 232–256. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v15i3.1821

Borup, J., West, R.E., & Thomas, R. 2015. “The impact of text versus video communication on instructor feedback in blended courses.” Educational Technology Research and Development, 63(2), 161–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-015-9367-8

Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2013). Rethinking models of feedback for learning: The challenge of design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(6), 698–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2012.691462

Budin, M. (2014). Investigating the relationship between English language anxiety and the achievement of school based oral English test among Malaysian Form Four students. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 2(1), 67–79. https://www.ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter/article/view/32/9

Byrne, D. (2002). Interpreting quantitative data. Sage.

Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Cavaleri, M., Kawaguchi, S., Di Biase, B., & Power, C. (2019). How recorded audio-visual feedback can improve academic language support. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 16(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.16.4.6

Cavanaugh, A. J., & Song, L. (2014). Audio feedback versus written feedback: Instructors’ and students’ perspectives. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 10(1), 122–138. https://jolt.merlot.org/vol10no1/cavanaugh_0314.pdf

Chang, C., Cunningham, K. J., Satar, H. M., & Strobl, C. (2017). Electronic feedback on second language writing: A retrospective and prospective essay on multimodality. Writing & Pedagogy, 9(3), 05–428. https://doi.org/10.1558/wap.32515

Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques. Wiley.

Cunningham, K. J. (2019). How language choices in feedback change with technology: Engagement in text and screencast feedback on ESL writing. Computers & Education, 135, 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.03.002

Elola, I., & Oskoz, A. (2016). Supporting second language writing using multimodal feedback. Foreign Language Annals, 49(1), 58-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/flan.12183

Ene, E., & Upton, T. A. (2018). Synchronous and asynchronous teacher electronic feedback and learner uptake in ESL composition. Journal of Second Language Writing, 41, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2018.05.005

Evans, C. (2013). Making sense of assessment feedback in higher education. Review of educational research, 83(1), 70-120. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654312474350

Fey, S., Emery, M., & Flora, C. (2008). Student issues in distance education programs: Do inter-institutional programs offer students more confusion or more opportunities?. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(3), 71–83. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/104053/

Gillett-Swan, J. (2017). The challenges of online learning: Supporting and engaging the isolated learner. Journal of Learning Design, 10(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.5204/jld.v9i3.293

Harper, F., Green, H., & Fernandez-Toro, M. (2012). Evaluating the integration of Jing® screencasts in feedback on written assignments. In 2012 15th International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning (ICL), 26-28 September. (pp. 1–7). IEEE. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=6402092

Harper, F., Green, H., & Fernandez-Toro, M. (2018). Using screencasts in the teaching of modern languages: Investigating the use of Jing® in feedback on written assignments. The Language Learning Journal, 46(3), 277–292. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2015.1061586

Hattie, J. (2009). The black box of tertiary assessment: An impending revolution. In S. Davidson, (Ed.), Tertiary assessment & higher education student outcomes: Policy, practice & research, 259–276.

Henderson, M., & Phillips, M. (2015). Video-based feedback on student assessment: Scarily personal. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 31(1). 51–66. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1878

Henderson, M., Ryan, T., & Phillips, M. (2019). The challenges of feedback in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(8), 1237–1252. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1599815

Hoq, M. Z. (2020). E-Learning during the period of pandemic (COVID-19) in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: An empirical study. American Journal of Educational Research, 8(7), 457–464. http://pubs.sciepub.com/education/8/7/2/index.html

Huxham, M. (2007). Fast and effective feedback: Are model answers the answer?. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 32(6), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930601116946

Ishtaiwa, F. F., & Aburezeq, I. M. (2015). The impact of Google Docs on student collaboration: A UAE case study. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 7, 85–96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2015.07.004

Jamrus, M. H. M., & Razali, A. B. (2021). Acceptance, readiness and intention to use Augmented Reality (AR) in teaching English reading among secondary school teachers in Malaysia. Asian Journal of University Education, 17(4), 312–326. https://doi.org/10.24191/ajue.v17i4.16200

Kirkwood, A., & Price, L. (2014). Technology-enhanced learning and teaching in higher education: What is ‘enhanced’ and how do we know? A critical literature review. Learning, Media and Technology, 39(1), 6–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2013.770404

Kostka, I., & Maliborska, V. (2016). Using Turnitin to provide feedback on L2 writers’ texts. The Electronic Journal for English as a Second Language, 20(2), 1–22. http://tesl-ej.org/pdf/ej78/int.pdf

Lamey, A. (2015). Video feedback in philosophy. Metaphilosophy, 46(4–5), 691–702. https://doi.org/doi:10.1111/meta.12155

Lenkaitis, C. A. (2020). Technology as a mediating tool: Videoconferencing, L2 learning, and learner autonomy. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(5–6), 483–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1572018

Li, K., & Akahori, K. (2008). Development and evaluation of a feedback support system with audio and playback strokes. CALICO Journal 26(1), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.v26i1.91-107

Lipnevich, A. A., Berg, D. A. G., & Smith, J. K. (2016). Toward a model of student response to feedback. In G. T. L. Brown & L. R, Harris (Eds.). Human and social conditions in assessment, (pp. 169–185). Routledge.

Lunt, T., & Curran, J. (2010). ‘Are you listening please?’ The advantages of electronic audio feedback compared to written feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(7), 759–769. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930902977772

Mahoney, P., Macfarlane, S., & Ajjawi, R. (2019). A qualitative synthesis of video feedback in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(2), 157–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1471457

Mayhew, E. (2017). Playback feedback: The impact of screen-captured video feedback on student satisfaction, learning and attainment. European Political Science, 16, 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2015.102

McCarthy, J. (2015). Evaluating written, audio and video feedback in higher education summative assessment tasks. Issues in Educational Research, 25(2), 153–169. http://www.iier.org.au/iier25/mccarthy.html

Nemec, E. C., & Dintzner, M. (2016). Comparison of audio versus written feedback on writing assignments. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 8(2), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2015.12.009

Octaberlina, L. R., & Muslimin, A. I. (2020). EFL students’ perspective towards online learning barriers and alternatives using Moodle/Google classroom during covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Higher Education, 9(6), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v9n6p1

Oraif, I., & Elyas, T. (2021). The Impact of COVID-19 on Learning: Investigating EFL learners’ engagement in online courses in Saudi Arabia. Education Sciences, 11(3), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11030099

Orlando, J. (2016). A comparison of text, voice, and screencasting feedback to online students. American Journal of Distance Education, 30(3), 156–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2016.1187472

Parkes, M., & Fletcher, P. (2017). A longitudinal, quantitative study of student attitudes towards audio feedback for assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(7), 1046–1053. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2016.1224810

Patton, C. (2012). ‘Some kind of weird, evil experiment’: Student perceptions of peer assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 37(6), 719–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.563281

Pitt, E., & Norton, L. (2017). ‘Now that’s the feedback I want!’ Students’ reactions to feedback on graded work and what they do with it. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(4), 499–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2016.1142500.

Robinson, S., Pope, D., & Holyoak, L. (2013). Can we meet their expectations? Experiences and perceptions of feedback in first year undergraduate students. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(3), 260–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.629291.

Saeed, M. A., & Al Qunayeer, H. S. (2020). Exploring teacher interactive e-feedback on students’ writing through Google Docs: Factors promoting interactivity and potential for learning. The Language Learning Journal, 50(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2020.1786711

Salmon, G. (2014). Learning innovation: A framework for transformation. European Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 17(1), 219–235. https://old.eurodl.org/?p=archives&year=2014&halfyear=2&article=665

Susanti, A., & Tarmuji, A. (2016). Techniques of optimizing WhatsApp as an instructional tool for teaching EFL writing in Indonesian senior high schools. International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature, 4(10), 26–31. https://doi.org/10.20431/2347-3134.0410005

Sekaran, U. (2006). Research methods for business: A skill-building approach. Wiley.

Tai, J., R., Ajjawi, D., Boud, P., Dawson, & Panadero, E. (2017). Developing evaluative judgement: Enabling students to make decisions about the quality of work. Higher Education. 76, 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0220-3

Thomas, R. A., West, R. E., & Borup, J. (2017). An analysis of instructor social presence in online text and asynchronous video feedback comments. The Internet and Higher Education, 33, 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2017.01.003

Tseng, S.-S., & Yeh, H.-C. (2019). The impact of video and written feedback on student preferences of English speaking practice. Language Learning & Technology, 23(2), 145–158. https://doi.org/10125/44687

Voelkel, S., & Mello, L. V. (2014). Audio feedback–better feedback?. Bioscience Education, 22(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.11120/beej.2014.00022

West, J., & Turner, W. (2016). Enhancing the assessment experience: Improving student perceptions, engagement and understanding using online video feedback. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 53(4), 400–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2014.1003954

Winstone, N. E., Nash, R. A., Parker, M., & Rowntree, J. (2017). Supporting learners’ agentic engagement with feedback: A systematic review and a taxonomy of recipience processes. Educational Psychologist, 52(1), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2016.1207538