Martina Šindelářová Skupeňová, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6643-6649

Radim Herout, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

Šindelářová Skupeňová, M., & Herout, R. (2024). Fostering students’ self-directed language learning: Approaches to advising. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(2), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.37237/150206

Abstract

This paper describes and discusses how two formats of advising in language learning offered at the Masaryk University Language Centre attempt to respond to students’ needs in self-regulating their learning. The focus is on comparing the advising sessions incorporated into an elective L2 course aiming at learner autonomy development and the sessions offered in obligatory L3 courses. A small study was conducted in both settings, identifying differences between students’ previous experiences, skills and expectations. Furthermore, two cases of individual advisees were analysed to gain a deeper insight into how similar students are supported by the different advising formats and available choices about their language learning. The case studies briefly portray how advising sessions navigate students in choosing their learning materials or methods. The aim of the paper is to illustrate that allowing students to make decisions about their language learning fosters their self-regulated learning.

Keywords: advising in language learning, self-directed learning, self-regulating learning, learner autonomy, language of advising, choosing learning methods

Learner autonomy support has gained more attention among language teachers in the Czech Republic quite recently. In the Masaryk university context, the growing numbers of students, the call to address their increasingly diverse needs and the experience of online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic all intensified the focus on how to support students in self-directed language learning and develop their learner autonomy. This article explains how advising in language learning is conceived at the Masaryk University Language Centre as a tool fostering students’ autonomy and helping them to self-regulate their learning. Two different formats of language advising sessions are introduced and compared, focusing on the languages targeted and used in the advising sessions and on choosing methods for learning English (L2) and German (L3) in a self-directed way. The aim of this paper is to discuss how both advising session formats respond to students’ needs in learning a second and third language and foster their learner autonomy.

Advising in Language Learning and the Target Language

Advising in language learning (ALL) is defined as a pedagogical tool focusing on the learning process and allowing students to reflect on their learning experience. This resource aims at helping students to self-regulate their learning (Mozzon-McPherson, 2001; Carson & Mynard, 2012). The language advising session should lead to a reflective dialogue, allowing students to evaluate the way they learn and to look for ways to learn more effectively (Mynard, 2020). Advising sessions are often offered to students who learn a foreign language in a self-directed mode. Thus, advisors attempt to help students with planning their learning, setting their goals, and choosing learning materials and methods. The aim of advising sessions is to foster students’ autonomy and support them when regulating their learning (Kato & Mynard, 2016).

For some scholars, the use of the target language (TL) is crucial for learner autonomy development, and they argue for using the target language not only in language learning activities but also in reflective and metacognitive activities, such as in advising reflective dialogues (Little et al., 2017). However, in some advising contexts, it seems to be more appropriate to rely on students’ native language (L1) or give students a choice. Gremmo (1995) opposes the idea of conducting advising sessions only in the target language, emphasizing the importance of learners being able to discuss their language learning experiences with ease. Thornton (2012) further discusses the reasons for preferring L1 as a possibility to distinguish advising from teaching and a chance to reassure learners as far as their language proficiency is concerned. Thus, the arguments for using L1 in an advising context are based on the wish to reduce the advisee’s cognitive or affective load. The two different formats of ALL compared in this article both aim at leading a reflective, learning-centred dialogue which helps students regulate their learning process. However, they differ regarding the voluntary or required role of advising in the course and regarding the language targeted and used during the advising sessions. This article is an opportunity for us to compare both formats and to investigate how they fulfil their functions.

Masaryk University Settings

Let us now describe in greater detail the two different settings in which language advising sessions are offered at the Masaryk University Language Centre. Advising in language learning was first introduced there in 2012 as a crucial element of the English Autonomously (EA) course. Since then, this elective course has been offered to students of various faculties and programmes, and it aims at developing their language skills as well as promoting their learner autonomy. As such, the course includes many metacognitive and reflective tasks, which the students are expected to perform in the target language. The recommended minimum entry level is B2, and for the vast majority of the students, English is their first foreign language (L2). The advising sessions are organised as a series of three individual meetings between an advisor and a student, and the students are required to participate in them. Furthermore, they also conduct self-assessment, do needs analysis and write reflective texts in English, including their language learning history and learning log. For many of the tasks, the students are given choices of what tools or methods they can use, but they are always expected to perform the tasks in the target language. This setting corresponds to the fact that the course is elective, and thus only taken by students who want to develop their language competences by using English also for regulating their learning, reflection and advising.

The ALL practice at the Masaryk University was first started by a small team of EA advisors who have been continuously developing their advising skills, e.g. through observations, peer reflections and training sessions. Their positive experience with and enthusiasm for ALL was further shared with other language centre teachers who were interested in finding ways to support students in self-directed learning or in developing their learner autonomy. In 2019, a special interest group focusing on learner autonomy support was established and it has organised several events promoting language advising competences as a part of professional teacher development. Based on these activities, ALL became a component in intensive courses of Czech for Foreigners as well as courses of English and German at the Faculty of Education. It is the language advising sessions offered to students of German for Future Teachers courses (GFT) that are analysed and compared to the EA advising context in this paper.

Contrary to the setting in EA, attendance at advising sessions is not required in GFT courses; they only represent an additional option and students decide themselves whether they want to participate in them or not. This is to allow even students in obligatory courses to make the most choices possible about their learning journey. As an incentive to attend the advising sessions, the students get bonus points for participation, which count towards their final mark (5 out of 100 points). To increase the number of choices made by the students and to lower the anxiety factor mentioned by Gremmo (1995), the students can also choose the language of advising, so the sessions can either be conducted in Czech or in German. The importance of this factor in the GFT course is related to the fact that German is typically the third language the students learn (L3) and their language level is about B1. The possibility to use their first language during the advising sessions should allow them to feel more relaxed and confident in expressing their thoughts and needs. Although approximately a third of the students choose German as the communication language used in their advising sessions, the majority accept the possibility to use Czech.

When contrasted to EA, students enter the GFT course with a very different motivation. While EA students typically choose this elective course to try out a different approach to developing their language skills, the students attending GFT are, in fact, forced to do so by the university language policy, which requires them to learn a second foreign language. The vast majority of them would probably not enrol in a L3 course if they did not have to. This is often related to previous negative experiences with learning German at primary or secondary school. Therefore, one of the functions and common topics of the GFT advising sessions is addressing critical issues related to the German language itself or to the process of learning the language in the past.

However, just like in EA, the advising sessions aim at helping students to self-regulate their language learning and their focus lies on students’ out-of-class learning activities. Since the aim of this paper is to investigate how both language advising formats respond to students’ needs and expectations, we conducted a survey and two case studies in our courses.

Survey

The survey was carried out in both courses after the concept of advising in language learning was introduced and explained. All students were asked to fill in a short questionnaire. The survey focused on students’ previous experience with self-directed learning, abilities to self-regulate their learning and expectations of what an advisor should help them with. Students’ responses were analysed before the first advising sessions took place, and data about the respective groups were compared and interpreted to find out whether the groups approach ALL with a different starting position. We expected that L3 learners would have more previous experience with self-directed learning as they have already reached a C level in L2. We also wanted to check whether there is a difference in what L3 and L2 learners need and expect from their advisors.

The aim of the case studies was to provide a detailed comparison of how advising functions in our L2 and L3 settings. For the studies, we selected one student from each course based on criteria that included overlapping characteristics of both groups. These selection criteria enabled us to focus on the distinguishing features and perspectives of each setting. The criteria were derived from course data, students’ language learning histories, and survey results. After selecting students with appropriate profiles, their data were individually analysed focusing on what support they sought and received during advising sessions. Finally, we compared both cases to explore differences and similarities in learning German as L3 and English as L2.

Survey Results

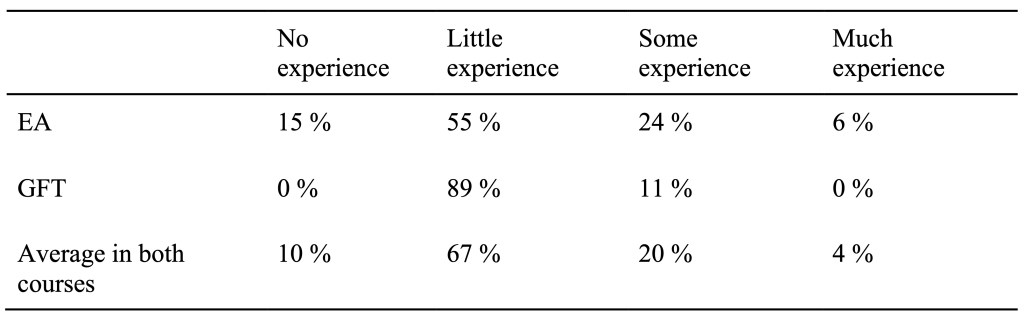

Although the survey was very basic, it provided us with interesting data and helped us to understand the students’ expectations and starting points better. The sample consisted of 33 responses from EA and 18 responses from GFT students. As for the inquiry about their previous experience, the majority of students in both courses (67 %) claimed that they had little experience with self-directed learning. Table 1 presents an overview of all responses.

Table 1

Experience with Self-directed Learning

When both groups were compared, the trend was even stronger in GFT where 89 % of students claimed little previous experience (55 % in EA), only 11 % of students reported some previous experience (24 % in EA) and no student reported much previous experience (6 % in EA) with self-directed learning.

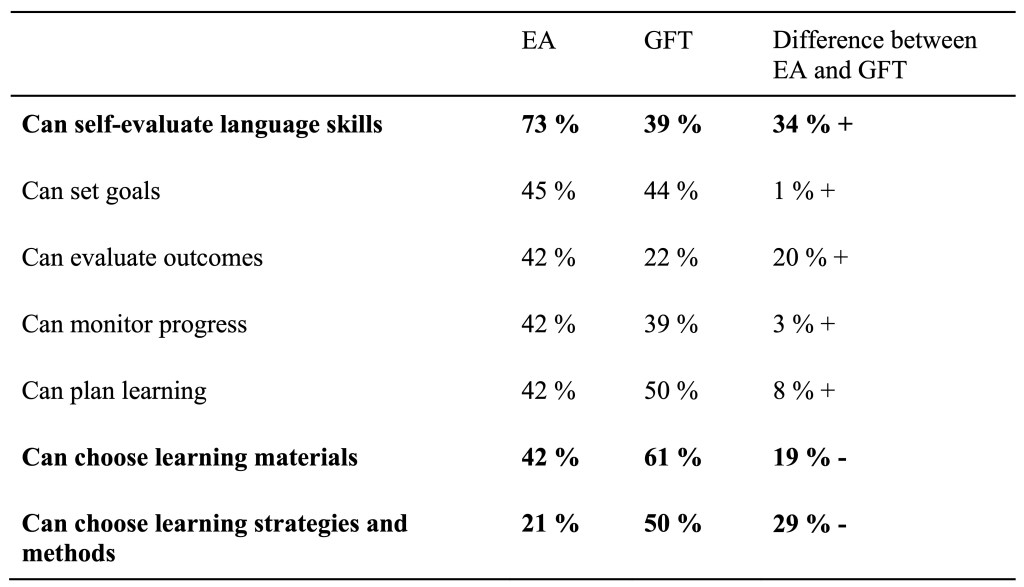

The survey included a self-assessment section in which students were asked to evaluate their abilities to regulate learning by choosing the applicable descriptors. These “can do” statements, e.g. “I can set my learning goals” were derived from Tassinari’s model of learner autonomy (2012) and the survey included seven meta-descriptors. The following table shows the results in both groups.

Table 2

Students’ Self-assessment of Abilities to Regulate Learning

When comparing the group results, three descriptors suggested interesting differences between the groups as highlighted in bold. In general, EA students are more confident about their abilities to regulate learning. The highest percentage of EA students (73 %) reported that they can self-evaluate their language skills, while only 39 % of GFT students claimed to have this ability. On the other hand, just 21 % of EA students claimed that they can choose learning strategies and this skill was the least claimed one in the EA group. This contrasts with 50 % of GFT students who reported that they have this skill. Even a higher percentage of GFT students (61 %) claimed that they can choose learning materials; this skill was also less frequently chosen by EA students (42 %). Overall, the self-assessment produced rather diverse results between both groups.

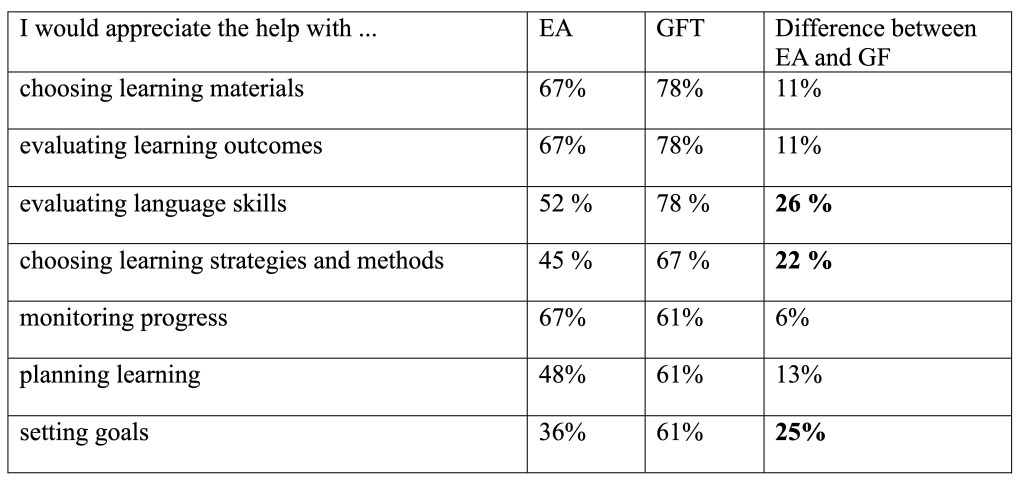

The students’ expectations regarding the advisor’s help were also investigated in the survey. For this inquiry, the seven above-mentioned learner autonomy descriptors were adapted into items such as “I would appreciate the teacher’s help with setting the learning goals”. On the whole, the results showed that the majority of students expect the advisors’ help in multiple areas. Table 3 introduces the results in this section of the questionnaire in more detail.

The English word “teacher” as well as the Czech “vyučující” and the German “Lehrende” were used in the question because the survey was introduced in a classroom setting and because Czech students might not be familiar with the terms “advisor in language learning” / “jazykový poradce” / “SprachlernberaterInnen”. However, it was explained to the students that they were being asked about the help they expect from meeting with the teacher in an individual advising session.

Table 3

Students’ Expectations Regarding the Advisor’s Help

The GFT students expect the advisors’ help even to a higher degree, as each item was chosen by more than 60 % of GFT students. The most frequently selected item by both groups was “help with choosing learning materials” and “evaluating learning outcomes”, opted for by 67 % of EA students and 78 % of GFT students. The biggest difference in what each group expects arose in “help with evaluating language skills”, which was an item chosen by 78 % of GFT students and 52 % of EA students. A significant difference also appeared between more GFT students expecting “help with setting goals” and “help with choosing learning strategies and methods”. The notable differences are highlighted in the table above.

Survey Findings

Our survey suggested that there are some differences between how both observed groups approach the advising sessions. In contrast to our expectations, the GFT group learning their third language claimed to have less previous experience with self-directed learning. Even if the GFT students were more confident about their abilities to choose learning materials and methods than EA students, they still expected the advisor to help with these choices and in other areas of self-regulating learning. The EA students claimed to have fewer self-regulating skills, but they reported less expectancy about the advisor’s help.

Case Studies

Based on the survey findings, we finalised the selection criteria for two small case studies which would enable us to get a better understanding of the differences between the two settings of our language advising sessions. As GFT students participating in the survey were enrolled on an M.A. programme and were learning German after English, we decided that also the selected EA students needed to have the same characteristics. Among the M.A. students who have been learning English as L2 and German as L3, we were looking for those who actually mentioned their experience with learning both languages in their advising session. Furthermore, we selected students who discussed their choices of learning materials or methods with their advisors. We focused on these topics because they were related to the differences between both groups discovered in the survey. By looking into the cases with similar profiles, we wanted to find out more about the support our advisees in an elective L2 course and obligatory L3 course get and about the choices they make.

Case 1: German for Future Teachers

GFT students are offered advising sessions both during their Bachelor’s and Master’s programmes. When selected for this study, the GFT student was attending an advising session for the second time; the first one had taken place approximately a year earlier as an addition to his Bachelor course. Hence, the advisee could comment on his language learning progress and reflect on his motivation development since the first advising session.

During the first GFT course, the advisee struggled with A2-level tasks and German language in general, mentioning inefficient and tedious classes at primary and secondary school, a common recollection of many students at the faculty. Particularly students majoring in English experience difficulties in perceiving any sense for them in learning another language as they presume that they will not have many opportunities to use it in the future. Still, completing the course is crucial for them since it is an obligatory part of the curricula in all educational programs. Since these limitations applied to our case, the advisee’s motivation to develop his German language skills was minimal when he enrolled on the first course.

However, it may have been the case that the advisee became interested in the possibility of recasting the trajectory of a failing learning process and demotivation, given that he voluntarily chose to attend the optional advising sessions in the GFT course. As he is majoring in English with a minor in History, the focus of the first session was to identify methods of learning English that proved effective for him and enabled him to achieve C1 level. The interview revealed that the student was not fully aware of the fact that he can apply the very same practices to learning other languages too. The follow-up aim of the session became to encourage transfer of these practices to the process of learning German. At the same time, the advisee and advisor were looking for learning materials that would appeal to his interest in history. Both of these shifts in the advisee’s approach to learning German should have increased the student’s motivation and fostered his self-regulated learning out of class.

Allegedly, this endeavour succeeded: After a year, the student reported that he is much more dedicated to learning German, using methods similar to those previously used in learning English (watching videos, speaking with peers, making notes) and concentrating on materials dealing with history for his out-of-class learning activities. As a consequence, the advisee started to perceive learning German to be more meaningful than before. During the second advising session, he commented on his recent learning experience: “I clearly see my progress. Things now come spontaneously into my mind in German, which I consider a good sign. Now, I feel better with my German than ever before.” Thus, it can be stated that participation in elective advising sessions in L1 helped the advisee to gain more confidence and get better at self-regulating his learning process. The advisor’s contribution in this case was to sensibilize the student about his preferences in language learning while helping him to choose methods and materials that correspond to his needs. In that respect, the advising sessions fulfilled their function as a supportive, choice-based element of the GFT course by helping the student navigate his way towards more autonomous learning, increasing his motivation and fostering his language competences.

Case 2: English Autonomously

The student selected for the EA case study chose to enrol in the course because he felt that his English language skills were deteriorating as there were few opportunities for him to practise them in more challenging situations. During the first advising session, he described that after he had completed a compulsory B2 English course in his Bachelor’s programme, he only had very few occasions to use English speaking skills in his studies. He also explained that his language learning history had involved about 15 years of English learning both in and outside of class, 4 years of German learning primarily in class, and that he had never attended a language advising session. Nevertheless, he declared that he understands the benefits of this tool and is interested in trying it out. The use of the TL in reflective and metacognitive activities did not represent a problem for him; actually, using English in a new context with a high cognitive load corresponded with the aims he chose to follow in the course.

When explaining his current motivation and needs to develop English skills, the advisee reported that he felt confident about communicating in everyday situations and about understanding both written texts and various types of audio input. In addition, he stated that his aim for the course was to transform his natural routines related to English into new learning opportunities and to find ways to practise more advanced speaking skills. As a result, the focus of the first advising session was on finding methods of using authentic materials and developing speaking skills outside of class.

During the session, the advisor helped the student recall ways of learning languages that he had found efficient in the past. The advisee highlighted the impact of playing video games on his English-speaking skills development. Furthermore, he realised that what used to make this learning experience both enjoyable and successful was the fact that he could immediately apply and practise the newly acquired language. On the other hand, he mentioned that this learning method had not worked for learning German. When asked to analyse this failed attempt at out-of-class learning, he reported: “I was trying to force myself into playing video games in German, but it was terrible, boring and not helpful.” Reflecting on this negative experience further, he commented on the lack of opportunities to use the newly learnt content in his German classes as those were “only preparing for the test and I started to hate them.” The advisee observed that his frustration about learning German language resulted from not being able to establish a connection between the in-class use of the language and his informal out-of-class learning.

After these contrastive experiences were analysed during the advising interview, the session aimed at choosing functional learning methods for the advisee’s current aim. Building on the positive practises of learning English, the student decided to plan opportunities for speaking which are directly linked to his usual English language input, which are related to his interests and, thus, meaningful for him. Having learnt from the boring and disconnected German learning experiences, he was looking for ways to involve some partners that he might address in speaking at least asynchronously. Recalling the unsuccessful transfer between gaming in German and more formal in-class use of the language, he also chose to frame the speaking activities so that they are both challenging and relevant for his studies. As a result of these considerations during the advising session, the student decided to practise his speaking by producing short audio reports on the materials he would watch and to conceive them as semi-formal, structured reviews that he would share with his friends.

Therefore, it can be concluded that the student’s participation in the advising session supported him in critically evaluating the previous learning experiences, transferring the positive practices into his new learning plan and also reflecting on the obstacles encountered when learning German. The reflective dialogue with the advisor allowed positive reframing of the language learning choices, so the student got to overcome the experience of forcing himself or being forced to use inefficient learning methods. The advising session fostered the student’s existing skills to self-regulate his learning and helped him to develop them.

Conclusion

In this paper, we depicted two formats of advising in language learning offered in various courses at the Masaryk University Language Centre and explained how they reflect different course settings and students’ starting points. We first carried out a survey to better understand our students’ previous experience with self-directed learning, their self-regulating skills and their expectations about advising in language learning.

The data indicated that the vast majority of the students have little experience with self-directed learning. As for advising, most students in both settings expect advisors’ help in numerous areas, the help with choosing learning materials being the uppermost preference for GFT students and a rather strong preference among EA students. An interesting difference between the two groups appeared regarding self-assessment and expectations about choosing learning strategies and methods. The advisor’s help in this area was highly expected in the GFT group, but only weakly anticipated in the EA, which contrasts with high self-assessment of the related skill by GFT students and low self-assessment by the EA group.

Subsequently, two case studies were conducted to provide more insight into the needs of our advisees and their gains from the advising process. These studies focused on comparing how the students work on choosing materials and methods during the advising sessions. Both advisees, who were learning English as L2 and German as L3, reflected on their previous learning experiences before considering their current goals: Using Czech as the language of advising, the GFT student first needed to identify successful language learning methods he used when learning English. Then, he was able to start transferring them from English to German language learning. Furthermore, with the help of the advisor, he managed to find learning materials which are engaging enough to increase his interest and motivation for learning German as an obligatory L3. The EA student first critically evaluated his previous experience with learning both English and German. On this basis, he was capable of transferring the positive factors into his new plan for English learning. Besides including previously efficient methods and deciding on using authentic engaging materials, the advising sessions also helped him to learn from analysing learning methods which had not worked for him in the past. The participation in the advising interview in the target language allowed the student to both plan and start advanced speaking practices that correspond to his needs and aims.

Despite various distinctions between the courses and advising settings, both students could benefit from advisors’ support when choosing or specifying their methods and materials so that they align with their needs, interests and goals. Therefore, we believe that both formats allow for individualised support and respond to students’ expectations and needs. Informed by this study, the advisors’ practice in both courses can aim at helping students develop their learner autonomy step by step by allowing them to make appropriate choices about their learning. When giving students the possibility to choose the language of advising in optional sessions and to select advising topics in both settings, the advisors focus on self-regulating skills that are relevant for each individual student at a particular stage of their language learning journey and both advising formats attempt to foster rather than force the learner autonomy development.

Notes on the Contributors

Martina Šindelářová Skupeňová is an English lecturer at the Masaryk University Language Centre. She is interested in promoting autonomy in various teaching and learning scenarios. Martina has contributed to the English Autonomously project from its beginning. Her Ph.D. research project investigates the influence of language advising on learner autonomy development.

Radim Herout is a German lecturer at the Masaryk University Language Centre, specializing in flipped classroom techniques and fostering student autonomy in language learning. With a focus on innovative teaching methods and advising, Radim aims to motivate students to take control of their language acquisition journey.

References

Carson, L., & Mynard, J. (2012). Introduction. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 3–25). Pearson.

Gremmo, M-J. (1995). Conseiller n’est pas enseigner: Le rôle du conseiller dans l’entretien de conseil [Counselling is not teaching: The role of the counsellor in the counselling session]. Mélanges CRAPEL, 22,33–62. https://www.atilf.fr/wp-content/uploads/publications/MelangesCrapel/file-22-12-2.pdf

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016) Reflective dialogue advising in language learning. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Little, D., Dam, L. & Legenhausen, L. (2017). Language learner autonomy: Theory, practice and research. Multilingual Matters.

Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2001). Language advising: Towards a new discursive world? In M. Mozzon-McPherson & R. Vismans (Eds.). Beyond language teaching towards language advising (pp. 7–22). The Centre for Information on Language Teaching and Research (CILT).

Mynard, J. (2020). Advising for language learner autonomy: Theory, practice, and future directions. In M. J. Raya & F. Vieira (Eds.), Autonomy in language education: Theory, research and practice. Routledge.

Tassinari, M. G. (2010): Autonomes Fremdsprachenlernen: Komponenten, Kompetenzen, Strategien [Autonomous foreign language learning: Components, skills, strategies]. Peter Lang.

Tassinari, M. G. (2012). Evaluating learner autonomy: A dynamic model with descriptors. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(1), 24–40. https://doi.org/10.37237/030103

Thornton, K. (2012). Target language or L1: Advisors’ perceptions on the role of language in a learning advisory session. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 65–86). Pearson.

Appendix

Questionnaire