Jo Mynard, Kanda University of International Studies, Chiba, Japan. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0363-6461

Mynard, J. (2024). Self-access language learning support in Europe: Observations and current practices. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(2), 258–278. https://doi.org/10.37237/150209

Abstract

This research examined the practices and spaces for self-access language learning (SALL) support, such as self-access learning centers (SALCs), learning resources, other learning spaces, advising, learner development, and social learning opportunities in leading institutions in Europe. The researcher analyzed how language learner support is conceptualized, operationalized, and evaluated at three institutions in Italy and one in Germany. The research was conducted through systematic observations during site visits, document analyses, and semi-structured interviews with staff and students in the four institutions. The researcher also drew on findings from the recent literature, insights from recent conference presentations, and discussions with colleagues based elsewhere in Europe to make observations about current trends in SALL in Europe. Six themes emerged from a thematic analysis of this data. The research offers perspectives for students and teachers interested in supporting learning outside the classroom in Europe and elsewhere.

Keywords: self-access language learning, Europe, learner support, case study

Background

This paper explores how institutions can support language learners outside the classroom in developing both language skills and learner autonomy. The field of language learner autonomy originated in Europe in the late 1960s (Holec, 1981; Little, 1991). Learner autonomy is the ability of someone to take control of their language learning (Benson, 2011). In order to develop autonomy and take control, learners need to be supported, particularly if they have been accustomed to traditional classroom methods that are not conducive to promoting autonomy. Learner autonomy can be encouraged by gradually giving learners more control over the content and methods of learning, helping them to plan, set goals, choose resources and strategies, experiment with different ways of learning, and evaluate their process and progress. Promoting learner autonomy can be initiated in regular language classrooms, but learners must have access to support outside the classroom (Curry et al., 2017; Mynard, 2019).

The present research aims to see how language learner support outside the classroom is conceptualized, operationalized, and evaluated at leading language learning centers in Europe. Through a detailed study of four institutions as case studies and a broader exploration of other data, I analyze trends and make observations about self-access language learning (SALL) in Europe. This region has been relatively underrepresented in the self-access literature recently. By conducting this research, I aim to raise awareness of the importance of supporting language learners outside the classroom, highlighting directions that might be useful to self-access practitioners based elsewhere. Before describing the research, I will briefly review the relevant literature in the next section.

Self-Access Language Learning (SALL) and the Promotion of Learner Autonomy

SALL is broadly defined as supported language learning outside the classroom, requiring a degree of autonomous learning. Learner autonomy draws on several theoretical stances (Chong & Reinders, 2022) and is primarily understood as a learner’s active engagement with their language learning process. To paraphrase the so-called Bergen definition of learner autonomy, we can say that it is a learner’s readiness, willingness, and ability to take charge of their learning in pursuit of their own goals and needs, in collaboration with others as a social process (Dam et al., 1990).

Providing SALL opportunities in conjunction with the promotion of learner autonomy at an institutional level often includes the presence of a self-access learning center (SALC). Interest in SALL has evolved and expanded over five decades (Gardner & Miller, 2017; Mynard, 2022, 2023), and the field continues to develop based on emerging pedagogical trends, as well as technological development/ accessibility. SALL began in Europe in the 1960s with the relatively simple aim of providing worksheets for self-study outside the classroom. Since then, it has gone through several phases and has evolved into a multifaceted and complex field. The current understanding of SALL has incorporated knowledge and findings from fields including education, applied linguistics, psychology, leadership, adult education, counseling, psychotherapy, architectural design, and library sciences. Current conceptualizations of SALL are those of complex and dynamic social ecosystems (Murray, 2017; Mynard, 2022; Thornton, 2020). Mynard et al. (2022) reviewed the wider literature and examined how it contributes to a reframing of SALL. A recent definition of a SALC is “a supportive, meaningful, inclusive and person-centered social learning environment that intentionally and actively promotes language learner autonomy” (Mynard, 2023, p. 21).

Self-directed learning is a concept associated with SALL. It draws on work in adult education (e.g., Knowles, 1975) and includes systematic training in practical approaches for taking charge of one’s learning. In language learning, this often includes helping learners analyze their language-related needs, set goals, create a learning plan, choose resources and strategies, implement their plan, monitor their learning progress, and evaluate linguistic outcomes (Takahashi et al., 2013). Reflection greatly facilitates this process and should be embedded in the teaching and advising processes (Lyon, 2023). Some institutions offer specific self-directed learning courses where learners are helped with developing the self-directed skills they need in following their self-designed learning plan. In other institutions, self-directed learning might be embedded into a regular language course or offered as workshops or optional modules, often in a SALC (Kato & Mynard, 2016).

Support for learners engaging in SALL should ideally include access to advising in language learning (ALL), which takes the form of one-to-one reflective dialogues between a learner and a trained learning advisor. These dialogues aim to promote deep reflection in pursuit of language learner autonomy (Carson & Mynard, 2012; Kato & Mynard, 2016). Advising is an important support mechanism for language learners working without a teacher outside the classroom. ALL puts the needs of the student first and is not constrained by curriculum or other institutional or other external goals. Ideally, learners focus on issues that are important to their personal goals, and ALL respects their autonomy in choosing what to focus on in the advising sessions and their SALL in general without judgment.

In some cases, examinations are particularly important and might be a priority for the learner. According to Gödeke and Tonellotto (2023), around 70% of the advising at their large public university in Italy relates to supporting learners in passing required examinations. Although there are many ways to evaluate learning, depending on a learner’s goal, exam-based assessments are generally required for demonstrating language proficiency, particularly as part of course acceptance or graduation criteria. Exam-based evaluation might be the only kind of evaluation that students are familiar with, yet it is worthwhile helping them discover other ways to self-assess in order to measure their progress toward their goals.

Supporting learners outside the classroom is skilled work, requiring knowledge of not only language and pedagogy but also knowledge of other fields, for example, psychology, leadership, and technology. Teachers often need some training to promote SALL effectively. Leni Dam (2023) notes that it is important that teachers maintain current knowledge of the field and adapt to change. A teacher’s attitude to change has a great influence on their teaching. In-service training and teacher networks play an important role in the quality of education that students receive.

Another new development in recent years is that AI has been incorporated into SALL, which will affect our practice. For example, AI can be used as a personal assistant and help learners plan appropriate activities through discussion with an AI interface. Underwood (2024) shows how learners in a self-directed learning course can be trained in AI so that they can design tasks that match their language goals. Garro (2023) discusses how AI can contribute to the autonomous development of advanced English oral skills at the university level by using a purpose-built application drawing on AI. When used appropriately, such technology could fill a gap, particularly in providing learners with access to speaking practice opportunities (Zanca, 2023). Integrated appropriately into the learning process, it can promote learner autonomy and language proficiency.

A final point to make in this section is related to diversity and inclusion. Universities and education ministries recognize the importance of supporting learners’ diverse needs in times of rapid change and often draw on the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework, which has its roots in neuroscience. Through instructional design, UDL aims to remove barriers to learning by offering options for diverse learners (Burke et al., 2024). SALL is an approach compatible with inclusive practices (Pemberton et al., 2023; Watkins et al., 2023) and should provide access opportunities for all learners regardless of gender, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, first language, ability-based diversity, and other factors.

The Research

In this project, I investigate how SALL is conceptualized, operationalized, and evaluated in leading language learning centers in Italy and Germany. In order to do this, I formulated three specific research questions:

RQ 1. How is learner support conceptualized? (i.e., vision, mission, philosophy, aims)

RQ 2. How is learner support operationalized? (i.e., systems and support services)

RQ 3. How is learner support evaluated? (i.e., how can we say if the mission is being achieved?)

In addition, I planned to make observations about SALL in Europe in general and formulated one additional research question. Several sources informed my analysis for RQ4: the findings of the first three research questions, insights from the recent relevant literature, recent relevant conference presentations, and informal opportunistic discussions with leading scholars based elsewhere in Europe (namely, Austria, Denmark, Norway, Switzerland, Ireland, and Iceland).

RQ 4. What are the current trends in SALL in Europe?

Methodology

I adopted a case study methodology for this research. A case study approach is appropriate for this project as it is ideal for exploring in-depth phenomena in real-life contexts where the phenomena and contexts are interconnected (Yin, 2009). In addition, a case study methodology provides a suitable framework when dealing with various contributing factors evidenced by diverse data from multiple sources in unique settings. I have applied the transdisciplinary framework of complex dynamic systems theory (Douglas Fir Group, 2016; Larsen-Freeman, 2017) to guide the research direction due to the interconnectedness of the data. The project is framed as an interpretative study, drawing mainly on qualitative data.

Researcher Positionality

Although I am an experienced language educator with more than 20 years of experience working in SALL contexts, my role in this study is as an outsider-researcher. I had no previous connections to any of the institutions prior to this study. There are benefits and drawbacks to this stance when investigating my research questions. For example, in terms of benefits, the research sites were subject to my unbiased observations due to my unfamiliarity with the contexts (countries and institutions) and their usual procedures. My interview questions and site-visit checklists were formulated with the genuine intention of having a better understanding of practices. In terms of drawbacks, I did not have a deep understanding of the contexts myself, and I had to rely on my interpretations of the data I collected. I attempted to mitigate this disadvantage by asking my participants to read my interpretations and offer additional comments on my summaries. It is also worth noting that this process was beneficial for the participants themselves. Some of them mentioned that they appreciated the reflective questions I used during the interviews, and this helped them articulate their philosophy of learning and even make plans to improve their services.

Research Sites

I identified the four main research sites as they met the following criteria:

- They have well-established foreign language programs.

- The sites offer SALL support for learners.

- The academic staff in charge of the SALL services were in my professional network and agreed to help me with my study.

- The sites were within reasonable traveling distance from where I was based for one year during the study period.

For practical reasons, I focused on only four institutions; I only had one year to complete my data collection and analysis. I do not name the institutions for ethical reasons, but each institution has been given a code. I will describe each site briefly here.

Main Research Sites

- ITA1 (Italy). ITA1is a public research university and one of the oldest and most traditional universities in Italy. It has over 70,000 students, including undergraduates, postgraduates, and doctoral students. The university has 32 departments and eight schools. It has had a number of prominent graduates or professors over its long history. It is located in the center of one of the oldest cities in Italy, with a population of around 220,000. The city has a historical center and is the location of two UNESCO World Heritage sites. Despite this, it is not known as a tourist location; it is an industrial city where many Italian companies have their headquarters.

- ITA2 (Italy). ITA2 is a public research university and is over 150 years old. It is located in various buildings in a historical city, founded in the 8th century. It has eight departments and over 20,000 students, including undergraduates, postgraduates, and doctoral students. The historical city is a major tourist destination with a local population of around 50,000 inhabitants in the center of the university (around 250,000 in total, including the greater city area).

- ITA3 (Italy). ITA3 is a public university dating back to the 1600s in a city founded by the Etruscans around the fifth century BC. The university has nine departments and about 26,000 students. The city has a population of around 200,000 and is a center for gastronomy, but it is also known for its architecture and art.

- GER1 (Germany). GER1 was founded over 70 years ago and is a public research university consisting of 15 departments and institutes located in one of the largest cities in Germany. Most of the university facilities are located in the residential garden district of the city. There are around 38,000 students, including undergraduates, postgraduates, and doctoral students.

Other Sites Visited

- GER2 (Germany). University GER2 is one of the oldest public institutes of technology in Germany, founded in the mid-1700s. It has six faculties, and its programs are interdisciplinary, but they focus on aeronautics, engineering, manufacturing, and life sciences. The university has won architecture design awards for innovation and adaptability. It is located in a city of 250,000 people, dating from the 11th century AD. The city is a city of industry.

- ICE1 (Iceland). ICE1 is Iceland’s largest public research university. It was founded in the 1900s and has 14,000 students in 25 faculties. The main buildings are located near the center of a city of around 140,000 inhabitants. The main industries are tourism, fishing, and manufacturing.

Methods

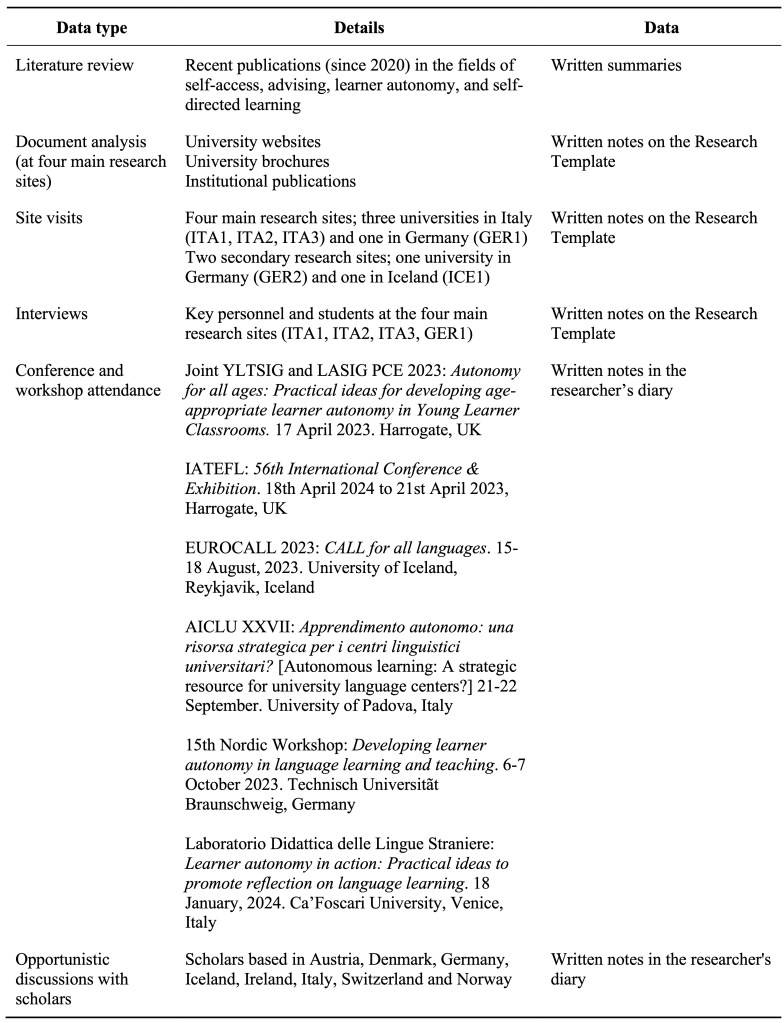

In order to answer my research questions, I reviewed the recent literature and also collected data from several sources. I divided my primary data into two types: (1) data collected at the four main research sites, which were three universities in Italy (ITA1, ITA2, ITA3) and one in Germany (GER1), and (2) opportunistic data collected elsewhere (see Table 1 for the details).

Data Collection

At the four main research sites, I conducted interviews, site visits, and document analyses, and I also made notes based on relevant discussions that occurred opportunistically. Mainly to substantiate my findings for RQ4, ‘What are the current trends in SALL in Europe?,’ my data collection consisted of two visits to secondary research sites, one in Germany (GER2) and one in Iceland (ICE1), fieldnotes based on opportunistic discussions with scholars based in Austria, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Norway, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, and my notes made during conference presentations or workshops at six relevant international events (held in Germany, Iceland, Italy, and the United Kingdom).

While reviewing the literature during the early stages of this project, I developed a Research Template that would allow me to collect and organize the data from each of the four main research sites systematically (see Appendix 1). The Research Template contained spaces for me to add details that would help me to answer the research questions, and I completed one version for each of the four main research sites. Before conducting the interviews at the main research sites, I completed as much of the information as possible based on my analysis of publicly available documents, such as websites, brochures, and publications. During the interviews, which were semi-structured in nature, I was able to confirm whether the information I had already collected was current, and I added more background and depth where necessary. Some information was not available at all in the public domain, so the interviews were essential for helping me to fill in the gaps. Each interview lasted between one and two hours and was with staff and students willing and available to be interviewed, typically SALC directors, program directors, learning advisors, instructors, students working in the SALC, graduate students, or recent graduates. I did not record the interviews, but I wrote notes in real-time, pausing to check my understanding or read back what I had written on the Research Template. Staff or students were also willing to give me a tour of the relevant facilities and introduce me to other colleagues working at the institution. During these tours, I took photographs and added further notes to the Research Template.

Table 1

Summary of Data Collected and Analysed

Data Analysis

In order to answer RQs 1 to 3, I referred to the completed Research Templates and summarized the findings from each of the four main research sites. I wrote a detailed case study for each of the sites, which included the following elements:

- overview of the institution and relevant department

- details about the learners and language proficiency

- details of the language programs and support offered

- facilities and resources

- support for teachers

- inclusive practices

- strengths

- challenges

- evaluation of SALL

These lengthy case studies will not be shared here, but I present the key themes in the findings section. In order to answer RQ4, I conducted a thematic analysis of all of my researcher diaries and relevant emergent elements of each of the Research Templates.

Findings

RQ 1. How is Language Learner Support Conceptualized? (i.e., vision, mission, philosophy, aims.)

Although two out of the four main research sites no longer have a physical SALC (ITA1 and ITA2), all four institutions have an understanding of the importance of promoting learner autonomy and supporting students outside the classroom in multiple ways. Self-access is generally conceptualized as the practical way in which learners are supported in their language-learning endeavors. Two of the centers (ITA3 and GER1) prominently display their mission statement and definitions of learner autonomy, demonstrating the importance of learners taking control of their own learning. The other two institutions (ITA1 and ITA2) have an assumed understanding and ensure that teachers are given the support they need to develop their learners’ independence.

RQ 2. How is Language Learner Support Operationalized? (i.e., support systems and services.)

Support for learning at all four sites is responsive to students’ needs. These include exam preparation, the development of awareness of language learning, and support for students with learning differences. Resources and facilities are designed to support learners in learning languages outside the classroom.

Exam Preparation

This takes the form of mock (practice) tests and courses specifically designed for exam preparation. In addition, students can take the tests regularly on campus. For example, at ITA1, instead of having to pay for international external tests such as TOEFL and IELTS, students can take an in-house equivalent test that is either free of charge or very economical. The tests are computer-based and take place in large labs. They are carefully designed to be the equivalent of CEFR bands. In ITA2, students can earn an Open Badge* for completing a self-directed language course (and the relevant assessment), indicating their CEFR level for the purposes of being admitted to a course or as a graduation requirement.

Development of Awareness of Language Learning

At three of the sites (ITA1, ITA3, and GER1), advising sessions are available from language experts with professional training as learning advisors. In ITA2, advising is available by counsellors. ITA2, ITA3, and GER1 provide courses and/or materials on learning strategies, making learning plans, or similar to support the development of autonomous language learning.

Support for Diverse Learners

Two institutions (ITA1 and ITA3) offer exceptional support for diverse learners, but all four institutions offer an advising service that can cater to diverse learners. All of the institutions follow legal requirements on inclusive education published in Europe. Educators take care to ensure accessible education to all learners.

Resources and Facilities

The physical SALCs at ITA3 and GER1 contained ample resources and facilities for language learners to use, such as hardware, resources (print and multimedia) for studying multiple languages, and study spaces. There are no longer physical SALCs at ITA1 and ITA2, and the former facilities are now mainly used to administer examinations. However, other facilities include libraries, multimedia laboratories, a media library, audiovisual and computerized resources, study rooms, workspaces, wifi, and printing/copying facilities.

Courses, Events, Workshops, and Support.

The institutions provided language instruction in a variety of languages (real-time / in-person classes and self-directed courses). At ITA2, library staff offer workshops on information literacy using an Open Badge* accreditation system. In addition, the libraries at ITA2 organize events such as guest lectures and workshops and hold regular exhibitions in the exhibition spaces.

RQ 3. How is Language Learner Support Evaluated? (i.e., how can we say if the mission is being achieved?)

SALL is evaluated at ITA1, ITA3, and GER1 through student surveys. GER1 is also planning more systematic research. Typically, staff working in the education sector are busy professionals focused on student support, which tends to be quite demanding work. Due to the nature of this service-oriented educational approach, finding time for research can be a challenge. In addition, all four centers reported feeling short-staffed, meaning that activities such as evaluation and research may not be feasible when they want to provide support services to students as a priority. A final challenge is the way that the roles of educators (i.e., language specialists, language instructors, and learning advisors) are conceptualized in Italy and Germany. Despite holding post-graduate diplomas and graduate degrees, the contracts for these educators state that the role does not include research. Many of the participants in my study recognized the importance of research that would inform and improve practice and, ultimately, the support that students receive, but stated that research needed to be done in their free time.

RQ 4. What Are the Trends in SALL in Europe?

Based on a thematic analysis of all of the data, six themes emerged that can help me to discuss the current trends in SALL in Europe and, to some extent, future considerations. These are presented in alphabetical order.

Theme 1: Assessment and Self-Evaluation

SALCs have a long history of providing exam-related resources, and this feature seems particularly prominent in some institutions nowadays. However, sometimes, the focus on success in formal assessments such as TOEFL and IELTS is at the expense of other kinds of activities, such as developing awareness of learning, developing communicative competence, or engaging in enjoyable or motivating activities through the target language. Unless there is action against this trend, the nature of SALL will shift to assessment rather than learning and language development.

Self-evaluation has always been an important part of SALL, and many centers have developed tools for learners to ‘diagnose’ their own strengths and weaknesses; this may need revisiting. SALCs need to consider whether the self-evaluation support and resources are prominent enough. Many centers in Europe routinely use the Council of Europe Framework of Reference (CEFR) resources, which are multilingual and effective tools for learners, advisors, and teachers (not only those based in Europe). A CEFR-informed approach to self-evaluation is more compatible with the promotion of learner autonomy (but may need to be updated in light of recent generative AI capabilities).

Theme 2. Generative AI

Generative AI is shaping applied linguistics in unprecedented ways. There is speculation about whether language teaching and learning will be necessary in the near future (Aikawa, 2024). Generative AI is likely to have an impact on SALL from now on, but during my observation period (April 2023 to March 2024), there were no significant modifications in practices from previous years. My data revealed that people working in these institutions possess a genuine passion for learning languages and the wish to support learners in enhancing their knowledge of the world and the cultures within it. Certainly, those with this view will always be interested in learning languages and sharing their passion. However, many people do not have an intrinsic interest in learning languages and may have, until now, needed to learn languages for functional purposes, for example, to access resources, take classes, or be able to travel easily abroad for work. From now on, for those guided by these extrinsic motivations, AI is likely to be used as a time-saving measure, such as translation/interpretation, basic communication, or information synthesis, which they may consider ‘good enough’ for their purposes. Indeed, AI can help people translate their ideas into other languages, but human connections and significant contributions to one’s chosen field may be limited. In order to really engage with an academic or professional community, people will still need to develop a certain level of proficiency in other languages. For people with a language base, AI can help them enhance their communication skills.

In terms of the emergent role of generative AI in SALL, learning advisors will certainly still be needed to help learners plan their language learning and use AI appropriately as part of this process. AI assistants could certainly support this role to a certain degree, but when dealing with complicated human emotions associated with language learning, i.e., anxieties, dreams, fears, motivations, and so on, the human-human interaction is likely to persist for the foreseeable future.

Theme 3: Inclusion

Learner autonomy approaches have always been learner-centered and focused on individualization and awareness of the language learning process. This is becoming a mainstream endeavor thanks to recent work and legislation in inclusive education. This means that all teachers need to cater to the needs of individual learners in every class, not just in the SALC or in self-directed learning courses. In many cases, teachers are already doing this., since they are becoming more aware of learners with learning differences, whether disclosed or not. Teachers are keen to ensure that their classrooms are ‘barrier-free’ and usually need some support with developing inclusive practices (Burke et al., 2024). More training and awareness raising is needed now and in the coming years to support teachers in helping their learners, particularly in developing awareness of the learning process and personal strategies for success in language learning, no matter what the disability or difference. SALL practitioners have a role to play in leading this process by providing accessible learning resources and, depending on their position in the university, becoming centers for teacher education (see Daloiso, 2024 and Daloiso et al., 2023).

Theme 4: Institutional Structure and Collaboration

All of the institutions I examined had a very different structure. Not all institutions have SALCs, but those who do seem to be connected with the Language Center. In some cases, they operate as independent units, but all of them serve the language needs of the students at their institutions. In some cases, the SALC or the Language Center takes the lead in the development of learning awareness by offering workshops, courses, or materials. In other cases, an independent unit at the institution offered this kind of personal development. In terms of future trends, it seems unlikely that there will not be one universal approach, but it might be more effective if SALCs are able to enhance their mission beyond just language to also focus on learner personal growth. This means that SALC directors need to be willing to develop expertise in several areas and draw on the training and knowledge from colleagues in the institution. For example, in ITA1, learning advisors benefitted from the knowledge supplied by their colleagues in the psychology department when supporting students with diverse needs. In GER1, collaboration with other departments ensured that appropriate resources were provided for learners outside the classroom.

Theme 5: Multilingualism

In Europe, people speak or understand a wide range of languages. It is usual for people to use multiple languages in daily life; there is more interaction between the ways in which languages impact each other during the language-learning process. In ITA2 and GER1, for example, there are courses and resident expert academics that focus on plurilingualism and multilingual education. In ITA2 and GER1, there are also specialist courses on the features of Romance languages. SALCs that focus only on one language or treat each language in isolation will be redundant in modern society. Instead, we should be encouraging translanguaging, i.e., a model where multilingual speakers draw on all of their available linguistic resources in communication (García et al., 2021). SALCs have a role in making connections between languages and providing opportunities for people to draw on several languages when developing their knowledge and communicative competence.

Theme 6: Teacher Education

In all of the centers I visited, language and pedagogy experts from language centers trained colleagues from different departments of their institutions in language and language pedagogy. They were also in demand to provide training for other institutions. Such training included foreign language instruction. For example, at ITA2, teachers who taught courses in English had to demonstrate a C1 level of English before they could offer such courses. With more institutions internationalizing and attracting more international students, more courses are being offered using English as a medium of instruction. Experts in diverse areas need to maintain their English language skills to continue teaching these content courses. They can do this through online SALL in collaboration with advising and also by attending traditional language classes from Language Center colleagues.

Another area where teacher education is needed is in providing language support within content classes. This is termed CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) or similar. ITA2 has an active program where content teachers can reserve consultation sessions with CLIL specialists, which might include observations and feedback sessions. Some institutions have team teaching where one content expert and one language specialist team up. However, this requires more teachers and precise organization, which can be unrealistic in some contexts. It seems more efficient to ensure that content teachers have access to the training they need in order to do both.

Conclusions and Recommendations

I began this project to explore SALL to enhance my knowledge and understanding of the field and improve how we support our students at my home institution. After a fascinating and enriching exploration, I have identified several areas that could be applied to work in SALL. Some priorities for SALC directors are to examine their current practices regarding the themes outlined in the discussion section and make a systematic plan for each area. I will finish by posing some questions for SALC directors and program leaders to consider in order to evaluate their current practices, identify areas to develop, and make a plan.

Theme 1: Assessment and Self-Evaluation

Assessment

- What proportion of SALC / SALL resources focus on the preparation of formal assessments such as TOEFL and IELTS examinations?

- How would you like this proportion to change in the next one, five, and 10 years?

- What steps need to be taken?

Self-Evaluation

- What proportion of SALC / SALL resources focus on self-evaluation?

- How would you like this proportion to change in one, five, and 10 years?

- What steps need to be taken?

- What self-evaluation tools and frameworks are used in SALL?

- Are they appropriate, or can other approaches be explored?

Theme 2: Generative AI

- How will generative AI affect the role of SALL in one, five, and 10 years?

- What are some of the opportunities and threats related to generative AI in SALL?

- How prepared are staff and students to utilize generative AI effectively for SALL?

- What steps need to be taken in the next few years?

Theme 3. Inclusion

- How dedicated are your institution and your department to promoting inclusion, diversity, and accessibility?

- Does your institution or center have a statement or goal in your mission statement related to inclusion (e.g., see Mynard et al., 2022)?

- What tools can help to remove barriers and make SALL support systems more inclusive (e.g., refer to UDL guidelines)?

- How prepared are staff to support diverse learners in SALL?

- How can they receive adequate training to support diverse learners?

Theme 4: Institutional Structure and Collaboration

- How integrated is your department into the structure of your institution?

- Which departments would you like to collaborate with most?

- What steps will you take to improve inter-departmental collaboration?

Theme 5: Multilingualism

- Which languages are supported in your SALC / center?

- Does your department have an explicit policy or statement about multilingualism?

- Are the languages represented appropriately to meet the needs of students?

- How can multilingualism be promoted in your SALC/center?

Theme 6: Teacher Education

- What are your team’s training needs? (See the other themes – AI, inclusion, assessment, multilingualism.)

- What expertise exists at your institution that you could draw on to enhance your team’s knowledge?

- What expertise does your team have that you could offer to colleagues?

Note*

What is an Open Badge?

Open Badge (OBI – Open Badges Infrastructure) is a technical standard developed by the Mozilla Foundation (https://openbadges.org/). More than fourteen thousand worldwide organizations have adopted this system to identify, recognize, gather, and narrate people’s competencies. Each badge demonstrates a set of standards assessed by a participating institution and can be displayed on an online profile or CV. In Italy, Open Badges that comply with the standard defined by Mozilla are issued by BESTR. (https://bestr.it/?ln=en)

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted between April 2023 and March 2024 and was made possible by a Kanda University of International Studies Research Grant. Special thanks go to numerous students and educators who graciously provided me with insights, in particular (in alphabetical order) Annika Albrecht, Carmen Becker, Micòl Beseghi, Mariana Bisset, Elena Borsetto, Anja Burkert, Michela Canepari, Ilaria Compagnoni, Caroline Clark, Michele Daloiso, Leni Dam, Sophie Gisler, Barbara Gödeke, Marco Lera, David Little, Anne Linda Løhre, Elina Maslo, Christopher McDonnell, David McLoughlin, Marcella Menegale, Lawrie Moore, Joy Ramos Gonzalez, Klaus Schwienhorst, Camilla Spaliviero, Maria Giovanna Tassinari, and Federica Tonellotto.

References

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. Routledge.

Burke, A., Young, D., & Cook, M. (2024). Barrier-free instruction in Japan: Recommendations for teachers at all levels of schooling. Candlin & Mynard ePublishing. https://doi.org/10.47908/30

Carson, L., &. Mynard, J. (2012). Introduction. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 3–25). Pearson Education.

Chong, S. W., & Reinders, H. (2022). Autonomy of English language learners: A scoping review of research and practice. Language Teaching Research, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221075812

Curry, N., Mynard, J., Noguchi, J., & Watkins, S. (2017). Evaluating a self-directed language learning course in a Japanese university. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 14(1), 37–57.

Daloiso, M., & Gruppo di Ricerca ELICom (2023). Le difficoltà di apprendimento delle lingue a scuola. Strumenti per un’educazione linguistica efficace e inclusiva [Language learning difficulties at school. Tools for effective and inclusive language education]. Erickson.

Daloiso, M. (2024, March 17). Inclusive language education and advising. Paper presented at the 4th RILAE Graduation Symposium [online]. Kanda University of International Studies, Chiba, Japan.

Dam. L. (2023). Making space for autonomy in an institutional environment: The past, the present, and the future. In K. Schwienhorst & J. Ramos Gonzalez (Eds.), Making space for autonomy in language learning (pp. 9–19). Candlin & Mynard. https://www.candlinandmynard.com/nordic14.html

Dam, L., Eriksson, R., Little, D., Miliander, J., & Trebbi, T. (1990). Towards a definition of autonomy. In T. Trebbi (Ed.), Third Nordic Workshop on Developing Autonomous Learning in the FL Classroom report. 11-14 August 1989 (pp. 102–103). University of Bergen. http://www.warwick.ac.uk/go/dahla/archive/trebbi_1990

Douglas Fir Group. (2016). A transdisciplinary framework for SLA in a multilingual world. Modern Language Journal, 100 (Supplement 2016), 19–47.

García, O., Flores, N., Seltzer, K., Li Wei, Otheguy, R., & Rosa, J. (2021). Rejecting abyssal thinking in the language and education of racialized bilinguals: A manifesto. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 18(3), 203–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2021.1935957

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (2011). Managing self-access language learning: Principles and practice. System, 38, 78–89.

Garro, D. (2023, September 21–22). Guiding university students through a (dystopic?) future: From AI to the café bar. Paper presented at AICLU XXVII, University of Padova, Italy.

Gödeke, B., & Tonellotto, F. (2023, September 21–22). Language advising and inclusion: A collaborative approach to empower students in the evaluation process. Paper presented at AICLU XXVII, University of Padova, Italy.

Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy in foreign language learning. Pergamon.

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge.

Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Cambridge Adult Education.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2017). Complexity theory: The lessons continue. In L. Ortega & Z-H. Han (Eds.), Complexity theory and language development: In celebration of Diane Larsen– Freeman (pp. 11–50). John Benjamins.

Little, D. (1991). Learner autonomy 1: Definitions, issues and problems. Authentik.

Lyon, P. (2023). Conclusions: How can we promote reflection on language learning? In N. Curry, P. Lyon & J. Mynard (Eds.), Promoting reflection on language learning (pp. 349–358). Multilingual Matters.

Murray, G. (2017). Autonomy and complexity in social learning space management. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.37237/080210

Mynard, J. (2019). Advising and self-access learning: Promoting language learner autonomy beyond the classroom. In H. Reinders, S. Ryan, & S. Nakamura (Eds.) Innovations in language learning and teaching: The case of Japan (pp. 185-220). Palgrave Macmillan.

Mynard, J. (2022). Reimagining the self-access learning centre as a place to thrive. In J. Mynard & S. J. Shelton-Strong (Eds.), Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom: A self-determination theory perspective. Multilingual Matters.

Mynard, J. (2023). Autonomy-supportive self-access learning: Meeting the needs of our students. In K. Schwienhorst & J. Ramos-Gonzalez (Eds.), Making space for autonomy in language learning (pp. 20–36). Candlin & Mynard. https://www.candlinandmynard.com/nordic14.html

Mynard, J. Ambinintsoa, D. V., Bennett, P. A., Castro, E., Curry, N., Davies, H., Imamura, Y., Kato, S., Shelton-Strong, S. J., Stevenson, R., Ubukata, H., Watkins, S., Wongsarnpigoon, I., & Yarwood, A. (2022). Reframing self-access: Reviewing the literature and updating a mission statement for a new era. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 13(1), 31–59. https://doi.org/10.37237/130103

Pemberton, C., Marzin, E., Mynard, J. & Wongsarnpigoon, I. (2023). Evaluation of SALC inclusiveness: What do our users think? JASAL Journal, 4(1), 5–31. https://jasalorg.com/evaluation-of-salc-inclusiveness-what-do-our-users-think/

Takahashi, K., Mynard, J., Noguchi, J., Sakai, A., Thornton, K., & Yamaguchi, A. (2013). Needs analysis: Investigating students’ self-directed learning needs using multiple data sources. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(3), 208–218. https://doi.org/10.37237/040305

Thornton. K. (2020). The changing role of self-access in fostering autonomy. In Jiménez Raya & F. Vieira (Eds.), Autonomy in language education: Theory, research and practice (pp. 157–174). Routledge.

Underwood, J. (2024, May 17–19). Reflecting on introducing generative AI into a self-directed language learning course [Conference presentation]. JALT CALL 2024. Meijo University, Nagoya, Japan.

Watkins, S., Marzin, E., & Hooper, D. (2023). Opening doors for all in self-access. JASAL Journal, 4(1), 1–4. https://jasalorg.com/opening-doors-for-all-in-self-access/

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th Ed.). Sage.

Zanca, C. (2023, September 21–22). ChatGPT and AI text generation tools as the new ‘language calculators’: Do we still need to learn and teach foreign languages? Paper presented at AICLU XXVII, University of Padova, Italy.

Appendix

Research Template

Institution name

Established

Address

Website

Subject specializations

Languages taught

Name of learning space

Website

Social media

Date Opened

Position in the institution

Key staff

Purpose / mission

Definition of learner autonomy?

Target users

Language supported

Opening hours

Details of the physical layout

Details of facilities

Details of physical resources

Details of online resources

Support mechanisms for learners outside the classroom

Support for teachers

Number of users

Why do students use the space/service?

Strengths

Weaknesses

How is the space evaluated? Plans for the future