Marcella Menegale, Department of Linguistics and Comparative Cultural Studies, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Italy. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6095-4648

Lucia Spricigo, Department of Linguistics and Comparative Cultural Studies, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Italy

(Although both authors have equally contributed to the conception and planning of this paper, the introduction paragraph, ‘Self-Confidence in Second Language Learning’, ‘The Role of Motivation and Positivity’, ‘Reason for the Replication Study’, and ‘Conclusions and Insights for Further Research’ should be attributed to Menegale, while ‘The Original Study and the Replication Study’, ‘The Adapted Version of the CBD’, and ‘Findings’ should be attributed to Spricigo.)

Menegale, M., & Spricigo, L. (2024). Enhancing L2 confidence through learning diaries: A replication study on Italian lower-secondary school students. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(2), 187–212. https://doi.org/10.37237/150205

Abstract

Drawing on the literature on self-confidence, motivational theories, and positive psychology in the field of language learning, the present paper aspires to contribute to the literature by discussing some key findings of a recent conceptual replication study. In the original study, Shelton-Strong and Mynard (2018, 2021) investigated the benefits of keeping a diary for university language students’ motivation and L2 confidence. The replication study by Spricigo (2023) aimed to confirm original findings within a different educational context. For this purpose, the research design underwent some necessary modifications justified by the need to investigate the efficacy of using diaries among Italian younger students (13-14 years old) and the applicability of the teaching intervention in a lower-school context. After briefly presenting the two studies, this article will discuss the main findings, with a special focus on the issue of integrating the diary into the lower-secondary school curriculum.

Keywords: self-confidence, motivation, positive psychology interventions, diary, reflection, language curriculum

One of the strongest beliefs about what triggers learning concerns the importance of the experience from which the entire process begins. This is why learners’ personal needs, practices, expectations, and beliefs are critical in educational student-centered educational approaches.

Helping language students reflect on their learning process is considered an effective way to promote meaningful learning as it enables them to gain awareness of what they do, thus increasing their sense of autonomy and control over learning. Yet, while engaging in reflective tasks may not necessarily improve performance, as metacognitive processes involve different factors with many variables, the simple fact of gaining a better understanding of one’s emotions and beliefs is significant (Swain, 2013). In this sense, reflection is a way to help students bring emotions to the surface. Specifically, the act of writing about one’s language learning episodes to uncover hidden beliefs and attitudes is considered as extremely supportive for developing learners’ identity in more general terms (see Mynard, 2023). However, engaging in reflective practice is not an easy task to accomplish, especially for young people. Therefore, this process should start as early as possible, to get students accustomed to thinking about their mental processes and finding their own efficient learning behaviours. This notwithstanding, studies addressing metacognition in younger learners are very scarce, especially if compared to the number of investigations conducted on adults.

Starting from these premises, the present paper aspires to contribute to the literature by discussing some key findings reported in a recent replication study. The original investigation conducted by Shelton-Strong and Mynard (2018, 2021) on the use of a confidence-building diary with university students was replicated with younger students aged 13–14 years old (Spricigo, 2023). The aim was twofold: first, to confirm or otherwise the results of the original study about the benefits of this reflective tool for students’ motivation to language learning; second, to understand to what extent the tool could have a sustainable application in the Italian school system at lower levels of education. After presenting the theoretical framework guiding the replication study, the methods and results of the two studies will be briefly compared. Subsequently, specific attention will be given to the replication study data concerning the feasibility and sustainability of integrating the diary into the lower-secondary-school language curriculum.

Self-Confidence in Second Language Learning

A large body of literature is concerned with the impact of students’ self-confidence in the learning process, both inside and outside the classroom. Self-confidence is considered a crucial factor in language acquisition, as it can significantly influence learners’ motivation, persistence, and overall performance in the learning process. According to MacIntyre et al. (1998), L2 self-confidence “corresponds to the overall belief in being able to communicate in the L2 in an adaptive and efficient manner” (p. 551). This belief is influenced by two components: a cognitive one, which regards self-evaluation of L2 skills, and an affective one, which relates to the anxiety or discomfort associated with the use of the L2. Although some research on the interplay between these two components of L2 self-confidence reports a negative correlation between language anxiety and both real and perceived L2 proficiency, other findings show that anxiety tends to diminish as proficiency and experience increase (for a review see Edwards and Roger, 2015). Furthermore, the perceived level of self-confidence seems to determine the extent to which a learner is willing to communicate, which means that the more confident a learner is in their linguistic skills, the more inclined to engage in conversation and interaction in the target language they will be. In fact, a high level of self-confidence serves as a driving force that enhances motivation and enables students to persevere through the difficulties they encounter during the learning process (Cook, 2008). Based on these assumptions, language education should aim at building more high-quality self-determined motivation so that students are willing to use the target language to interact and learn without relying almost exclusively on their teacher (McEown & Oga-Baldwin, 2019).

The Role of Motivation and Positivity

Among the many motivational theories that have appeared in literature, Self-Determination Theory (SDT) has consistently shown success and explanatory capability in understanding motivation for language learning in formal environments, thus proving to be “a well-established theory in language education” (McEown & Oga-Baldwin, 2019, p. 102). SDT provides a comprehensive framework for understanding various facets of motivation through a collection of six mini-theories, each addressing fundamental questions about the individuals, actions, contexts, timing, motivations, and mechanisms underlying human behaviour. These mini-theories function in concert, aiming to elucidate how individuals can enhance their motivation and lead more fulfilling lives. One is the basic psychological needs theory, where the term ‘psychological need’ is defined as “a psychological nutrient that is essential for individuals’ adjustment, integrity, and growth” (Ryan, 1995, p. 410). In this view, a particular desire or motive is considered to be a fundamental psychological need only if its fulfilment is not just beneficial but crucial for an individual’s well-being. This means that satisfying this desire is seen as essential for a person’s overall psychological health and functioning. Conversely, if this desire is not met, it can lead to negative outcomes such as feelings of passivity (lack of motivation or engagement), distress, or defensiveness (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). Ryan and Deci (2017) identified three psychological needs, the satisfaction of which is essential for flourishing and well-being: competence, autonomy and relatedness. ‘Competence’ refers to the need for learners to feel that the actions they take are effective and lead to desired outcomes. ‘Autonomy’ refers to their requirement for purpose, volition and personal fulfilment in their behaviour. ‘Relatedness’ refers to learners’ necessity to feel a sense of belongingness and connection with teachers and classmates.

Sustaining learners’ basic psychological needs by encouraging active participation, personal engagement, curiosity, and intrinsic goals, will likely make them feel a sense of achievement over time (Jang et al., 2012; Oga-Baldwin et al., 2017). Associated with feelings such as “engagement, meaning, positive relationships, and accomplishment” are also the sense of well-being and positivity, or “positive emotion” (Seligman, 2011, p.16). Positive emotions are said to aid “the building of resources,” as they have a tendency “to broaden a person’s perspective, opening the individual to absorb the language” (Gregersen et al., 2014, p. 193). Despite prevailing beliefs, it is inappropriate to assume that positive emotions will consistently result in positive behavioural outcomes, nor should negative emotions be automatically associated with negative behaviours (Oxford & Gkonou, 2021). While acknowledging the existence of negative emotions, MacIntyre and Gregersen (2012) maintained that these could be minimised by creating safe classroom environments and encouraging positive emotions, for instance, by helping students to look positively at themselves (Arnold, 2011). It is in fact through their conscious interpretation that emotions are transformed into feelings (Damasio, 2000). Although positive emotions have been widely discussed in the literature on Positive Psychology (PP) (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), the ways in which they influence foreign language learning have been vastly underestimated (Dewaele et al., 2023). If emotions in language education have the potential to strongly impact students’ learning, research on emotion regulation is imperative, and integration of affective strategy instruction into language teaching and learning should be intensified to effectively address this critical aspect (Gkonou & Oxford, 2019).

While research that incorporates emotional states into the design seems to be arduous to accomplish – especially with younger students, due to both methodological challenges of investigating cognitive and emotional abilities, and practical constraints of the school system – practices that encompass interventions to increase individual well-being, also identified as positive psychology interventions (PPIs), are more frequently implemented (Gregersen et al., 2014). PPIs are “treatment methods or intentional activities aimed at cultivating positive feelings, positive behaviours, or positive cognitions” (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009, p. 467) and can be introduced in the classroom with minimal requirements for time, materials, or expertise (Shankland & Rosset, 2017). According to MacIntyre et al. (2019), these kinds of interventions must be developed across multiple levels, including individual lessons, classrooms, schools, curricula, and educational departments or ministries. However, it is imperative to assess the efficacy of these practices using robust and suitable research methodologies, especially among various groups of language learners, as it cannot be assumed that these activities will produce identical outcomes. Therefore, “empirical testing of PP activities is necessary both to understand their effects and to refine the activities” (MacIntyre et al., 2019, p. 265).

Reason for the Replication Study

Acknowledging the need to expand empirical research in this field, in particular as regards young learners, Spricigo (2023) replicated a study that was originally aimed at investigating the influence of a reflective tool, the confidence-building diary, on L2 confidence and motivation among university students (Shelton-Strong & Mynard, 2018, 2021). The conceptual replication study (for a definition, see McManus, 2022) was conducted with younger and less experienced language learners, with a view to testing the use of the diary in a different educational context, namely, in lower-secondary school. In fact, while the majority of PPIs have focused on adults (Carr et al., 2021), there is also a field of research addressing interventions with young people. In their review of the literature, Owens and Waters (2020) identify three aspects that make PPIs for youths different from those for adults. Interventions need to consider: i) youth-specific developmental needs, encompassing factors such as language abilities, abstract thinking, and social skills (i.e., the kind of reflection we can expect from young students is different from what we can require from adults); ii) the heightened level of neuroplasticity during childhood and adolescence, which makes the brain particularly receptive to change (i.e., the amount of PPIs may differ from what is effective for adults); iii) the mode of delivery of PPIs, which for youths are generally facilitated and supervised by adults within specific settings (e.g., schools), whereas for adults are often more self-directed.

The aim of the replication study was, therefore, to experiment with the integration of the CBD into the Italian lower-secondary school curriculum to understand its efficacy and its sustainability within the language curriculum. In Italy, although interest in learning-to-learn-oriented approaches began around the 1980s, it is only in recent times that specific mentions have been included in ministerial policy school procedural guidelines across all levels of education. In fact, learner autonomy became a major objective in the 2012 ‘Indicazioni Nazionali per il curricolo della scuola dell’infanzia e del primo ciclo di istruzione’ (National guidelines for the curriculum of kindergarten and first cycle education), which addresses students up to lower-secondary school. Autonomy is here defined as:

having confidence in oneself and trusting others; appreciating one’s ability in doing things for oneself; knowing how to ask for help; being able to express dissatisfaction and frustration by working out answers and strategies; expressing feelings and emotions; taking part in decisions by expressing opinions, making choices and growing more and more aware of one’s own behaviour and attitudes. (Menegale & Pozzo, 2020, p. 330)

This need to foster students’ learning awareness of their attitudes and perceptions that can have either a positive or negative influence on learning has been further nurtured by the current focus, in Italy as in many other countries, on positive emotions and well-being by researchers and policy makers in the educational field. Indeed, at the end of 2018 an agreement was signed by the Italian Ministry of Education and the National Association of Psychologistsfor the promotion of a series of pedagogical actions aimed at fostering well-being in school and better conditions for more effective learning (MIUR, 2018). Among the actions considered, one involves working with students on their belief system, emotions and attitudes. At the beginning of 2023, a legislative proposal was approved for including skills linked to emotional intelligence and related abilities (such as conscientiousness, emotional stability, open-mindedness) in education (Camera dei deputati, 2023). The proposal also involved enhancement of “life skills,” namely, those skills that lead to positive and adaptive behaviours, which make the individual capable of effectively coping with the demands and challenges of everyday life (such as the ability to manage emotions, stress management, effective communication, empathy, creative and critical thinking, decisions and problem solving). It is in this context that the interest of Spricigo (2023)’s study and, subsequently, of this paper arose.

The Original Study and the Replication Study

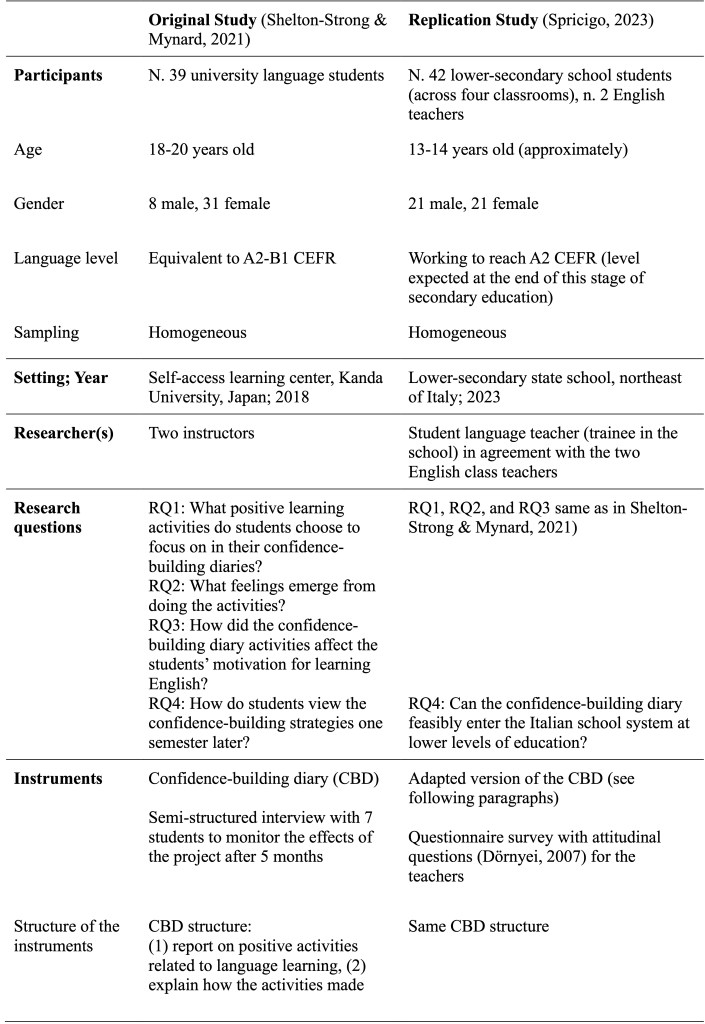

Shelton-Strong and Mynard (2018, 2021) employed the confidence-building diary (CBD) within a PPI-oriented programme with the aim of boosting university students’ confidence and positive attitude towards language learning and use. While maintaining a similar design and procedures, the replication study underwent some necessary modifications justified by the intention to address a different target and context. Commonalities and differences are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1

Original Study and Replication Study: A Comparison

The Adapted Version of the CBD

A number of modifications were required to adapt the reflection tool used to implement the PPI. In addition to considering the young age of the target participants, challenges related to conducting research in a school context were also taken into account, such as the limited time available for unplanned, optional projects. Specifically, the proposal for this intervention was presented to two English classroom teachers by a trainee teacher midway through the school year. The trainee teacher requested permission to develop this project with the teachers’ support during their regular curriculum. Given these considerations, three main aspects of the original CBD were identified as requiring adaptations: timings and introductory phase, language, and layout (for the adapted version of the CBD, see the Appendix).

Timings and Introductory Phase

While in the original study the CBD was employed as a weekly activity, in the replication study participants were required to complete the diary twice a week over a period of three weeks, though an additional week was agreed to allow them to complete the diary in all its parts. Likewise, also delayed submissions were accepted to acknowledge their efforts. Besides reducing workload, this aligns with the idea that a longer perseverance and exposure to PPIs can increasingly lead students to integrate them in their routine, thereby resulting in enhanced benefits (Seligman et al., 2005; Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2006). Learners could autonomously decide on which days they would like to engage in the English activities and hence they were free “to take charge of [their own] learning” (Holec, 1981, as quoted in Benson, 2007, p. 22).

For a gradual acquaintance with the new tool, learners were shown the instrument, explained its duration and compilation procedure, and reassured that their proficiency level would not be assessed by teachers. This is consistent with the idea that self-assessment is essential for comprehending one’s learning process and strategies, thereby enhancing learners’ awareness of their efforts. Moreover, students were made aware that, when learning a foreign language, there is often a tendency to concentrate on the negative, such as on one’s inadequate or lacking competence, rather than on the positive feelings associated with the learning practice. During these initial moments, in line with the concept of social capital (Nawyn et al., 2012), students had the opportunity to share their experiences of extracurricular language learning activities. Furthermore, the teachers and the researcher provided additional advice to expand their range of activities and raised their awareness of daily unconscious exposure to the target language.

Language Support

Unlike the original CBD, the adapted version employed the school language (namely, Italian) in some parts of the project, such as when introducing the tool, and in the diary, so as to support students from a linguistic and cognitive point of view. On the introduction page of the modified CBD, a suitable translation of the instructions was provided, and learners could use Italian to answer the last section regarding reflection. Moreover, to facilitate student’s use of the target language (English) some scaffolding techniques were implemented. For instance, before the diary entries, an example was provided to students – adapted from the one found in Shelton-Strong and Mynard (2021) – suitable for their specific educational context, their language level, and their daily life. Additionally, a series of useful sentence starters with a vast array of positive adjectives was introduced with the aim of helping learners express their feelings. Although not present in the original CBD-based intervention, likely due to the higher proficiency and age of their participants, this kind of language support was deemed necessary for the younger learners involved in the replication study. This choice took inspiration from a L2 class task proposed by Helgesen (2016), who, drawing on the ten forms of positivity by Fredrickson (namely, love, joy, gratitude, serenity, interest, hope, pride, amusement, inspiration, and awe; 2009), developed some “sentence starter cues” aimed at eliciting “positive emotions sentences” (p. 311).

Similarly, students were here provided with a list of cues that combined: i) the Positivity Self Test (Fredrickson, 2009), ii) the vocabulary found in the learners’ coursebook units about the topic of feelings and emotions, and iii) a selection of adjectives associated with the above mentioned ten forms of positivity. Each adjective was translated into Italian using reliable online dictionaries[3], which were also consulted to find additional and more suitable synonyms to the adjectives proposed by Fredrickson. With the purpose of ensuring variety and boosting learners’ lexis of feelings, some attributes that may appear to have overlapping meanings, were selected, e.g., ‘happy’, ‘joyful’, ‘glad’, and ‘thankful’ and ‘grateful’ for the forms of positivity of ‘joy’ and ‘gratitude’ respectively. Despite the helpfulness of this list, participants were left free to employ other phrases to express their feelings. In order to help learners construct their sentences, starters such as “I felt … / I was …” were added. Indeed, the guidance and opportunity to make choices are core elements of a teaching intervention aiming at fostering both autonomy and positivity at the same time.

New Layout

Participants were provided with a tool format different from the original one in accordance with the experiment duration and purpose. The diary was made up of six pages, namely two pages a week, progressively numbered. An additional unnumbered page was inserted at the end as a model to employ in the future by learners or educators. Students were provided with a considerably vast space for daily notes (A4 vertical sheet and half A4 horizontal sheet in the digital and printed version respectively) and could complete the diary either digitally or in printed form. The aim of such design was that of providing students with enough room for writing events, drawing, inserting images, and, for the digital version, to possibly include internet hyperlinks and other multimedia material. All this would likely promote personalisation of the tool and unleash students’ creativity, which is fully consistent with the scope of positive psychology interventions (Fredrickson, 2009). Moreover, the opportunity to add non-written elements to the CBD follows the conception of multimodality (Jewitt, 2009, as cited in Dubreil, 2021) and gives participants the opportunity to express themselves by using different modalities, thus making the diary more inclusive for low-proficiency learners.

Findings

In the following paragraphs, findings relevant to proving or otherwise the successful application of the CBD to another educational context will be discussed. In the original study, the tool was demonstrated to be “effective […] for promoting positive feelings and supporting students’ basic psychological needs” (Shelton-Strong & Mynard, 2021, p. 1). In the replication study, three factors were considered to validate the efficacy of the CBD, namely: i) students’ active and autonomous engagement in language learning activities; ii) the prevalent emergence of positive feelings; iii) students’ motivation, investigated also through the identification of basic personal needs.

Types of Preferred Language Activities

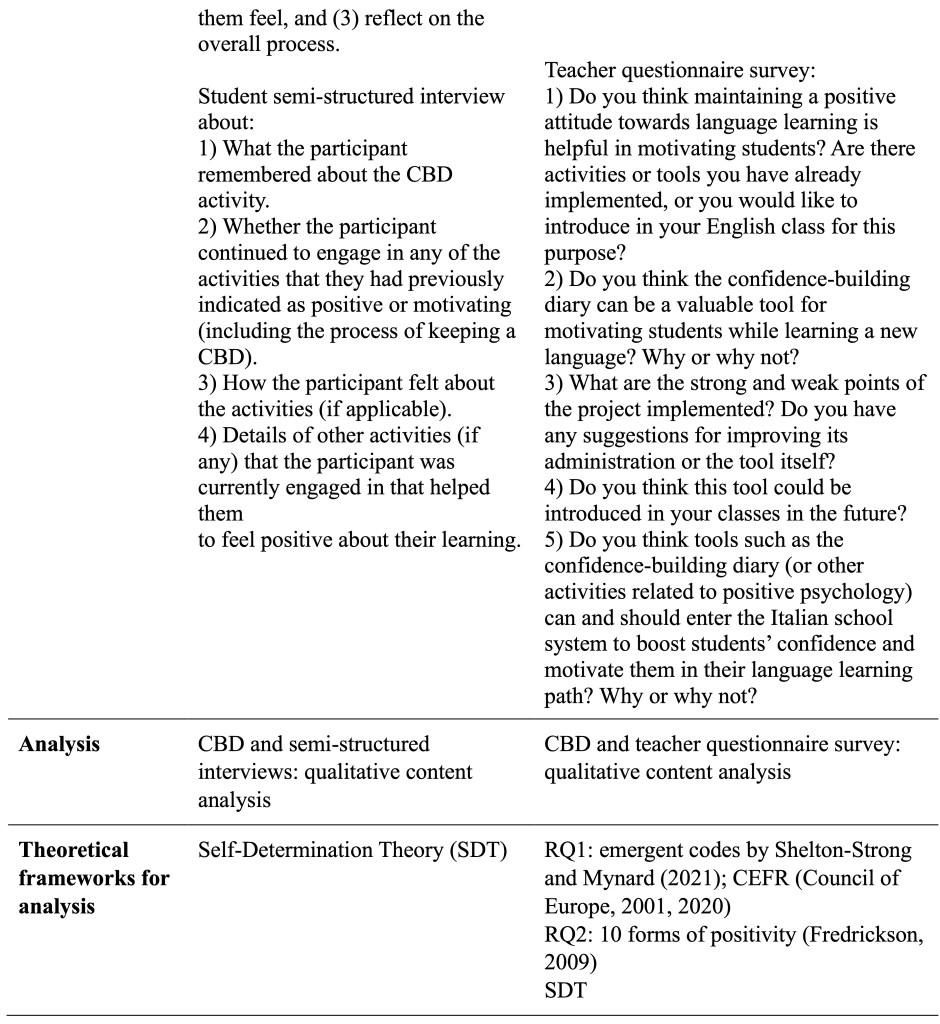

In Spricigo (2023), learning activities were first categorised into ‘in-class’ and ‘out-of-class’ activities, as in Shelton-Strong and Mynard (2021). In both studies it was found that the majority of learning activities that the students chose to focus on took place outside of the classroom environment. Furthermore, with the aim of investigating the nature of activities and student engagement further, Spricigo (2023) divided data into ‘school-related’ and ‘pleasure-related’ activities, which align with formal/curricular and informal/extracurricular learning, respectively (see Table 2 for details). Pleasure-related activities such as watching films or videos and listening to music were reported as the most frequent among young students.

Unlike the university students in the original study who preferred speaking activities, the younger students in the replication study were found to prefer receptive activities, through oral, written and multimodal input. This is likely due to the specific characteristics of these target students. Furthermore, given their low-level of L2 proficiency, it can be assumed that they feel more comfortable with receptive activities because they can process the language at their own pace. There is less pressure compared to speaking or writing, which can cause anxiety due to fear of making mistakes. On the other hand, at their age, they have limited opportunities to use the foreign language to communicate with other people, especially outside the classroom. Hence, it can be concluded that learners demonstrated the capacity to take control of their English practice, following their preferences for certain types of activities. This supports the idea that the PPI implemented might be successfully applied with lower-secondary school students.

Table 2

Language Learning Activities Context (adapted from Spricigo, 2023)

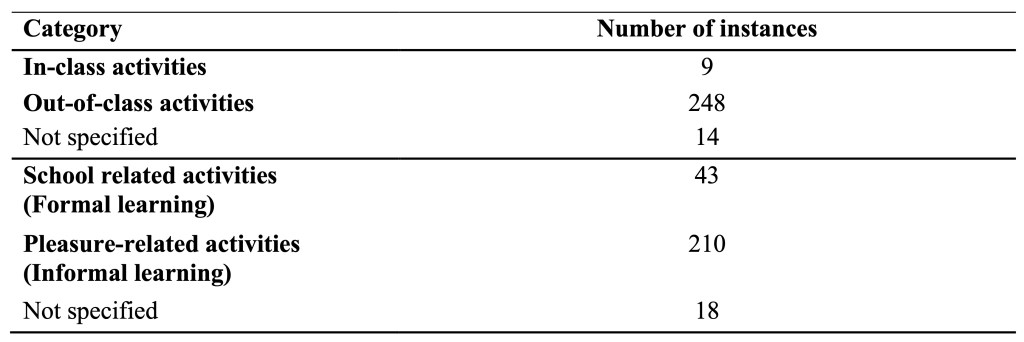

Feelings Emerged

In both studies, students were able to maintain a positive mindset when engaging in the learning practice and completing the diary. However, while Shelton-Strong and Mynard (2021) did not refer to a specific theoretical framework to categorise positive feelings, Spricigo (2023)’s analysis considered Fredrickson (2009)’s ten forms of positivity, which helped define students’ thoughts. Table 3 shows younger students’ perceived feelings across the three-weeks intervention (week 4 reports the feelings of those who completed the model inserted at the end of the diary). The considerable presence of ‘joy’ and ‘pride’ in learners’ entries suggests that keeping a CBD had a positive impact on their language learning experience. Interestingly, it was found that students experienced a feeling of ‘pride’ whenever they perceived a sense of competence, which is one of the basic psychological needs. Conversely, among the few negative feelings reported, ‘perceived complexity’ was experienced the most. This may be due to the fact that the possibility to choose, while beneficial for their autonomy, did not always lead learners to focus on carrying out activities that were adequate for their language level. Nonetheless, facing difficulty was in some cases combined with perseverance and satisfaction with one’s accomplishments, as the following extracts show:

“It was difficult, but I understand the words.”

“I’m very proud and pleased because it was difficult to read it, but I did it!”

Table 3

Positive and Negative Feelings (adapted from Spricigo, 2023)

Motivation

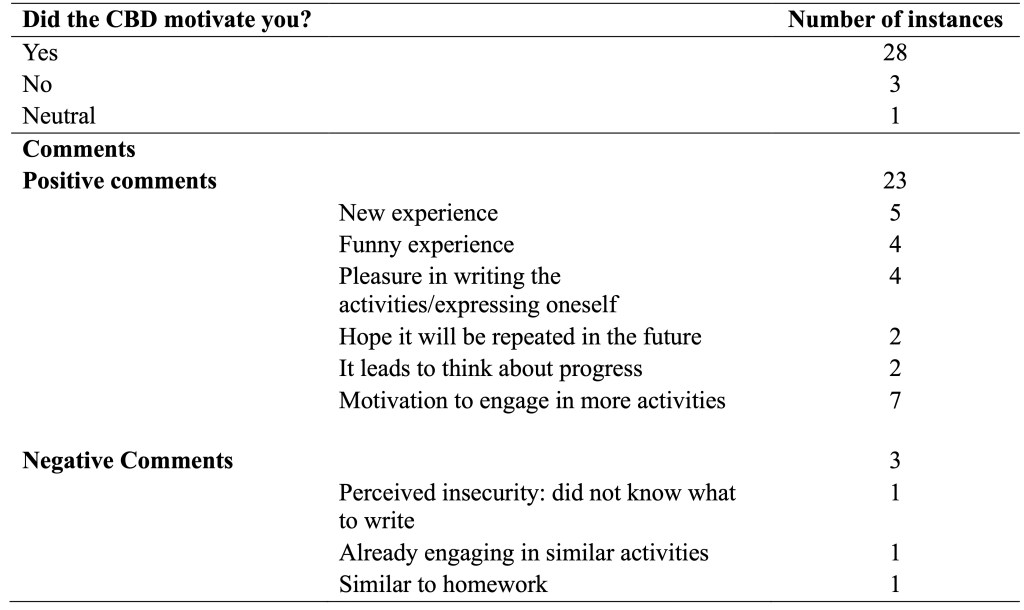

In the original study, all the participants felt that the CBD-based intervention was beneficial. In the replication study, although the CBD was generally well-received, a minority of participants did not find it motivating. Table 4 shows this data, also reporting the reasons given by younger students.

Table 4

Answer to the Question on Motivation (Spricigo, 2023)

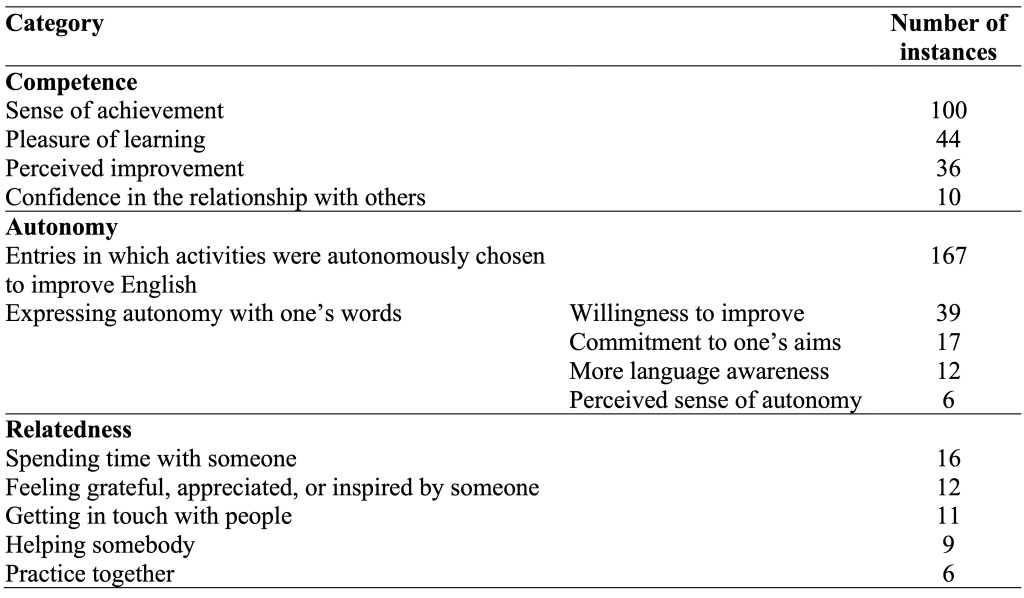

In relation to SDT, positive results emerged from the satisfaction analysis associated with basic psychological needs: a perceived sense of competence, autonomy and relatedness was found among both university students and younger ones. As for lower-secondary school learners, expressions related to students’ needs were investigated in each part of their diary (‘activities’, ‘feelings’ and ‘reflection’ sections) and categorised in major codes (see Table 5).

Table 5

Basic Psychological Needs (adapted from Spricigo, 2023)

Regarding competence, lower-secondary school learners mostly reported a sense of achievement for succeeding in carrying out an activity, such as translating, understanding, recognising, using or knowing English words, or having good results. Furthermore, students expressed their pleasure in learning the language, perceived improvement in their language skills, and confidence in the relationship with others when managing to communicate with other people. Autonomy was especially conveyed by participants’ engagement in tasks to improve their language level, also through self-initiated activities, and expressed by their willingness to improve and their commitment to their aims. This was particularly evident when they attempted to understand and use English for carrying out daily activities. It is worth noting here that the majority of students decided to use the foreign language to answer the CBD final reflective questions, hence indicating their readiness to challenge themselves despite their language level and age. Finally, relatedness was recorded when students spent time, practised, or got in touch with other people, felt grateful, appreciated, or inspired by somebody, and helped someone. All three basic psychological needs are present in the following excerpt:

“Activity: I was playing an online video game with people I didn’t know and to understand we spoke English.

Feelings: I was amused because many of the things they said I understood but some words I could not understand them and then I pretended to have understood and in the end we also won the game.”

A closer examination of the results related to the CBD modifications in the replication study revealed that the hypothesis that longer perseverance and exposure to PPIs would lead students to integrate them into their routine, thereby resulting in enhanced benefits, was not supported. In fact, after an initial enthusiasm for the activity, indicated by considerable participation in completing the diary during the first two weeks, a decrease in student involvement was recorded during the third week, with fewer learners addressing questions on motivation and positive language learning strategies. Possible reasons for this include an insufficient variety in their learning activities repertoire and partially developed metacognitive skills. Nonetheless, the decision of a few learners to continue engaging in the CBD by completing the final unnumbered page should be regarded as an encouraging and positive sign.

Another CBD modification applied to the replication study regarded the layout, which was changed to provide students with more space for writing events, drawing, inserting images, and, for the digital version, to possibly include internet hyperlinks and other multimedia material. It was hypothesised that this would likely promote personalisation of the diary and unleash students’ creativity, therefore boosting their motivation in completing the activity. However, findings revealed that the vast majority adhered to the provided CBD without personalising the tool in any way. Only three students did it when completing the diaries digitally, with two of them including images representing the activities they engaged in, such as a picture of popcorn when watching TV series, and one utilising graphics and emoticons to express feelings and decorate the diary. In addition to indicating a lack of interest in making the diary a personal tool, these results may also suggest that students are not used to expressing themselves through different modalities, preferring writing over multimedia materials.

Integration of the CBD Into the Lower-Secondary School Curriculum

All the findings and considerations mentioned above were taken into account to address the central question underlying the conceptual replication study: Can the CBD feasibly enter the Italian school system at lower levels of education? To widen the perspective, Spricigo (2023) included teachers’ voices in her study, through a questionnaire survey. The classroom teachers’ answers, in fact, proved to be crucial for the evaluation of the PPI intervention and its possible integration into the lower-secondary school curriculum. Generally speaking, the application of PPIs in the school system is regarded positively by both educators, who acknowledge that these actions can promote the development of soft skills and foster a positive teaching and learning outlook. They recognised the potential of reflection tools such as a learner diary to increase students’ awareness of language learning, with one teacher arguing that it leads to thinking about the important role of English as a means to comprehend the world surrounding them. Regarding self-awareness, the other teacher maintained that it is essential to develop it from a young age, hence validating the experimentation of the tool with younger students.

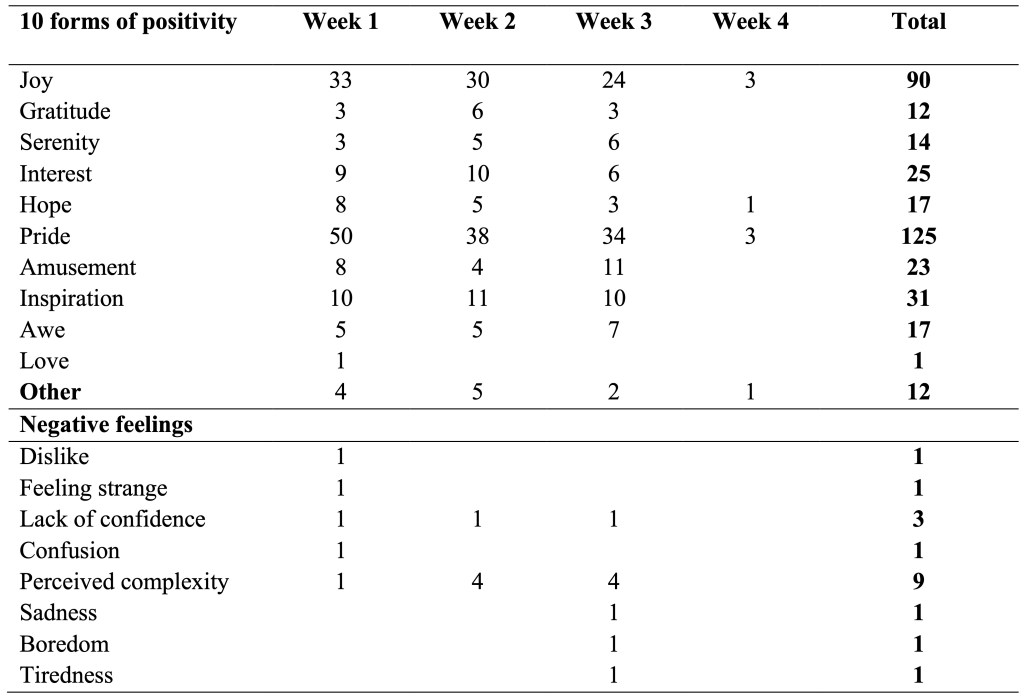

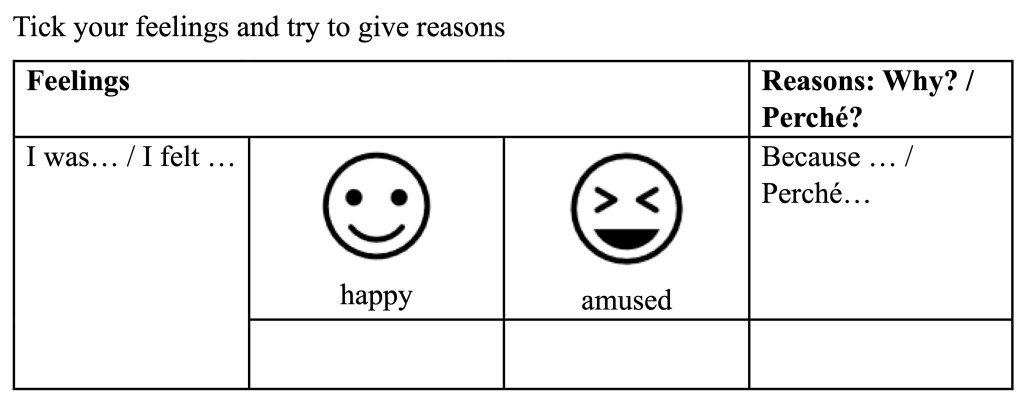

Nevertheless, when indicating the tool’s weaknesses, this same teacher suggested that the instrument should provide students with more guidance to cope with the possible difficulties they could encounter when reflecting on their learning. According to the educator, the task should be further simplified also from a linguistic point of view, indicating that the language scaffolding interventions made on the CBD were not sufficient. In this regard, a possible solution for young and less proficient learners may be a simplified table which would allow them to convey their feelings by ticking a box corresponding to an emoticon representing a certain positive adjective. An additional part could be included, for a detailed description of feelings for more competent and self-aware students. A possible example is showed in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Possible Simplified Diary (Spricigo, 2023)

Furthermore, one of the teachers proposed a more interactive solution, such as an online questionnaire or a mobile app, considering young learners’ high engagement in language learning activities through technological devices. It was also suggested that an online document where students can share their extracurricular learning could help them expand their individual language activities repertoire, thus aligning with the concept of social capital. On the whole, the two teachers reported different perceptions about the CBD at the end of the experiment. For one of them, the CBD is not a suitable tool for lower-secondary school learners, because, in her opinion, they are too young to effectively employ it. Conversely, the other teacher was more positive on the use of the tool with young students. She even went so far as to advocate for the future introduction of the diary in the curriculum, contingent upon a few modifications: i) its regular use from the first year of lower-secondary school, ii) the utilisation of a different format (paper or digital-based, but more user-friendly and easier to navigate), iii) having a specific time and space to complete it at school. All these suggestions are consistent with the need to adopt this type of PPI as a routine (Seligman et al., 2005; Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2006).

Conclusions and Insights for Further Research

It is widely acknowledged that for students to be successfully engaged in their language learning, they should encounter a positive learning environment where awareness (including that of emotions) is regularly part of the curriculum from early stages of learning. This notwithstanding, the literature in the field reports that activities aimed at fostering students’ reflection of their learning processes are generally introduced at the university level, or later.

This paper presents the main findings of a conceptual replication study (Spricigo, 2023) designed to validate on younger learners (13-14 years old) the results of an original investigation conducted on university students (Shelton-Strong & Mynard, 2018, 2021). The main challenges found in adopting a confidence-building diary with younger students regard the need for making the tool accessible from both a cognitive and a linguistic point of view. In fact, young students are not generally used to reflecting on their learning and on the emotions associated with their language experience. Furthermore, they often lack the language to express their feelings, either in their target language or, quite often, on their own. This means that they first need support in addressing these two aspects. It is widely accepted that ‘learning to learn’ is the result of a complex interplay of awareness and competence that are built up over time, which develop gradually when nurtured by conducive conditions. As observed in Menegale and Pozzo (2020), if teachers introduce tools that necessitate written reflection to foster metacognitive growth (such as diaries, guidelines for task review, self-assessment queries, etc.), they should not be discouraged if students initially refrain from writing. Rather, they should recognize that even silence can be revealing and requires strategies for expression. Thus, initiating a reflective dialogue about students’ actions and learning processes not only prepares them mentally but also equips them with the vocabulary to articulate their learning experiences. Engaging in stimulating discussions in pairs or small groups enables learners to identify shared feelings that they might have struggled to verbalise individually. Consistent with recent developments in literacy, it is also worth mentioning the importance of encouraging students to express themselves through various modalities and languages (words, images, drawings, etc.), so as to exploit all the communicative resources at their disposal in an efficient and critical way. This is in line with current educational policies recently put forward across countries (see, for example, Council of Europe, 2019; UNESCO, 2019). Nonetheless, students must understand the purpose of reflection explicitly: they embrace reflective practices only when they perceive their value, receive feedback, and witness tangible outcomes.

Despite acknowledging the challenges primarily associated with the practical implementation of the CBD-based activity in a lower-secondary school context, this paper manages to show that such reflective tools can effectively enhance younger students’ awareness of their language learning process and cultivate positive feelings towards their language learning journey. We saw in fact that younger students liked keeping a diary and felt their basic psychological needs satisfied while carrying out language activities.

While the limitations of the study, such as the narrow sample size and the restricted time devoted to the intervention, prevent a more in-depth analysis, the data from the diary experimentation with younger students, as discussed here, is certainly promising and deserves further investigation. This aligns with the need to expand empirical studies on the influence of positive feelings on maintaining motivation for sustained learning and to find effective ways to integrate affective strategy instruction into language teaching (Gkonou & Oxford, 2019). More specifically, further focus in the literature is needed to better understand the role that positive psychology interventions, such as the one here reported, may play in the language curriculum, especially at lower school levels. Although research in this setting is becoming increasingly challenging due to the intricate interaction among developmental, curricular, pedagogical, and assessment-related factors inherent in the educational context, this should not discourage or limit researchers’ pursuits.

Notes on the Contributors

Marcella Menegale, Ph.D. in Language Sciences, is a researcher in Educational Linguistics at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Italy, where she also directs the Laboratory of Foreign Language Didactics (LADILS). Her research interests include plurilingual approaches (especially CLIL and intercomprehension) and learner autonomy, with a strong orientation to psychological factors connected to language education.

Lucia Spricigo, Master’s Degree in Language Sciences at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, is currently working as a temporary primary school teacher, trying to promote learners’ wellbeing and positivity in her classroom.

References

Arnold, J. (2011). Attention to affect in language learning. Anglistik. International Journal of English Studies, 22(1), 11–22.

Benson, P. (2007). Autonomy in language teaching and learning. Language Teaching, 40(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444806003958

Camera dei deputati (2023). Competenze non cognitive e trasversali nei percorsi delle istituzioni scolastiche e dei centri provinciali per l’istruzione degli adulti, nonché nei percorsi di istruzione e formazione professionale. https://documenti.camera.it/leg19/dossier/pdf/Cost033.pdf

Carr, A., Cullen, K., Keeney, C., Canning, C., Mooney, O., Chinseallaigh, E., & O’Dowd, A. (2021). Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(6), 749–769. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1818807

Cook, V. (2008). Second language learning and language teaching. Hodder Education. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203770511

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Council of Europe/Cambridge University Press. https://rm.coe.int/1680459f97

Council of Europe. (2019). Global education guidelines: Concepts and methodologies on global education for educators and policy makers. https://rm.coe.int/prems-089719-global-education-guide-a4/1680973101

Council of Europe. (2020). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment –Companion volume. Council of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/common-european-framework-of-reference-for-languages-learning-teaching/16809ea0d4

Damasio, A. (2000). The feeling of what happens: Body and emotion in the making of consciousness. Mariner Books.

Dewaele, J.-M., Botes, E., & Meftah, R. A. (2023). Three-body problem: The effects of foreign language anxiety, enjoyment, and boredom on academic achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 43, 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190523000016

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford University Press.

Dubreil, S. (2021). Exploring multimodal literacies through the linguistic landscape in the L2 classroom: De-familiarize the familiar [PowerPoint slides from a CERCLL Webinar, Carnegie Mellon University]. CERCLL. https://cercll.arizona.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2021/01/CERCLL-Webinar-Dubreil-2021-compressed_1.pdf

Edwards, E., & Roger, P. S. (2015). Seeking out challenges to develop L2 self-confidence: A language learner’s journey to proficiency. TESL-EJ, 18(4).

Fredrickson, B. L. (2009). Positivity: Discover the upward spiral that will change your life. Harmony Books.

Gkonou, C., & Oxford, R. L. (2019). Teacher education: Formative assessment, reflection and affective strategy instruction. In A. U. Chamot & V. Harris (Eds.), Learning strategy instruction in the language classroom: Issues and implementation (pp. 213–226). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788923415-023

Gregersen, T., MacIntyre, P. D., Finegan, K. H., Talbot, K., & Claman, S. (2014). Examining emotional intelligence within the context of positive psychology interventions. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 4(2), 327–353. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.8

Helgesen, M. (2016). Happiness in ESL/EFL: Bringing positive psychology to the classroom. In P. D. MacIntyre, T. Gregersen, & S. Mercer (Eds.), Positive psychology in second language acquisition (pp. 305–323). Multilingual Matters.

Jang, H., Kim, E. J., & Reeve, J. (2012). Longitudinal test of self-determination theory’s motivation mediation model in a naturally occurring classroom context. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 1175–1188. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028089

MacIntyre, P., Clément, R., Dörnyei, Z., & Noels, K. (1998). Conceptualising willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. Modern Language Journal, 82(4), 545–562.

MacIntyre, P., & Gregersen, T. (2012). Emotions that facilitate language learning: The positive-broadening power of the imagination. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 2(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2012.2.2.4

MacIntyre, P., Gregersen, T., & Mercer, S. (2019). Setting an agenda for positive psychology in SLA: Theory, practice and research. The Modern Language Journal, 103(1), 262–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12544

McEown, M. S., & Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q. (2019). Self-determination for all language learners: New applications for formal language education. System, 86, 102–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.102124

McManus, K. (2022). Replication research in instructed second language acquisition. In L. Gurzynski-Weiss & Y.-J. Kim (Eds.), Instructed Second Language Acquisition Research Methods (pp. 103–122). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/dvmuq

Menegale, M., & Pozzo, G. (2020). The role of ‘learning to learn’ in second and foreign language education in Italy. In C. Ludwig, M. G. Tassinari, & J. Mynard (Eds.), Navigating foreign language learner autonomy (pp. 299–319). Candlin & Mynard.

MIUR (2018). Promuovere benessere a scuola. https://www.psy.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/PI-MIUR-e-CNOP-181218.pdf

Mynard, J. (2023). Promoting reflection on language learning: A brief summary of the literature. In N. Curry, P. Lyon, & J. Mynard (Eds.), Promoting reflection on language learning: Lessons from a university setting (pp. 189–205). Multilingual Matters.

Nawyn, S. J., Gjokaj, L., Agbenyiga, D. L., & Grace, B. (2012). Linguistic isolation, social capital, and immigrant belonging. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 41(3), 255–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241611433623

Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q., Nakata, Y., Parker, P., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Motivating young language learners: A longitudinal model of self-determined motivation in elementary school foreign language classes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 49, 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.01.010

Owens, R. L., & Waters, L. (2020). What does positive psychology tell us about early intervention and prevention with children and adolescents? A review of positive psychological interventions with young people. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(5), 588–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1789706

Oxford, R. L., & Gkonou, C. (2021). Working with the complexity of language learners’ emotions and emotion regulation strategies. In R. J. Sampson & R. S. Pinner (Eds.), Complexity perspectives on researching language learner and teacher psychology (pp. 52–67). Multilingual Matters.

Ryan, R. M. (1995). Psychological needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. Journal of Personality, 63, 397–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00501.x

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development and wellness. Guilford Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/978.14625/28806

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish. A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An

introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410

Shankland, R., & Rosset, E. (2017). Review of brief school-based positive psychological interventions: A taster for teachers and educators. Educational Psychology Review, 29, 363–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9357-3

Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(2), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760500510676

Shelton-Strong, S., & Mynard, J. (2018). Affective factors in self-access learning. Relay Journal, 1(2), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010204

Shelton-Strong, S., & Mynard, J. (2021). Promoting positive feelings and motivation for language learning: The role of a confidence-building diary. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 15(5), 458–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2020.1825445

Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating

depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20593

Spricigo, L. (2023). A study on the application of the confidence-building diary in the Italian lower secondary school. Unpublished master’s thesis. Ca’ Foscari University of Venice.

Swain, M. (2013). The inseparability of cognition and emotion in second language learning. Language Teaching, 46(2), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000486

UNESCO. (2019). UNESCO strategy for youth and adult literacy (2020-2025). https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000371411

Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion, 44, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09818-1

[1] Project carried out with headmaster’s, teachers’, and students’ consent.

[2] For details on the language proficiency levels identified by the Council of Europe in its Common European Framework of Reference for Languages see https://rm.coe.int/common-european-framework-of-reference-for-languages-learning-teaching/16809ea0d4

[3] Wordreference.com (https://www.wordreference.com/it/), Cambridge Dictionary (https://dictionary.cambridge.org/), and Thesaurus.com (https://www.thesaurus.com/)

Appendix