Graham Burton, Department of Education, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Italy. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8501-9207

Elena Borsetto, University of Verona / Free University of Bozen-Bolzano; Italy. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3760-054X

Alessandra Giglio, University of Dalarna / Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Italy

Leonhard Voltmer, Department of Education, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Italy

Burton, G., Borsetto, E., Giglio, A., & Voltmer, L. (2024). Creating a self-access academic writing centre at a trilingual university: What have we learned in the first three years?. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(2), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.37237/150202

Abstract

The Centre for Academic Writing at the trilingual (German–Italian–English) Free University of Bozen-Bolzano was created in 2021 as a means of supporting student writing at the institution and for carrying out research in academic writing and communication in plurilingual contexts. It offers a number of self-access services, specifically credit-bearing courses, writing groups, and a Helpdesk service. This paper provides an outline of these services, discussing challenges encountered, how they have been addressed and how the services have evolved as a result. It offers a particular focus on the Helpdesk service, with an analysis of the kinds of queries most commonly received from the students. The data suggests that students most frequently access the helpdesks having received negative feedback from a supervisor on their writing, and most generally have queries relating to structure and citations, with linguistic issues rarely addressed.

Keywords: writing centres, academic writing, self-access centres, higher education

This paper reports on the activities at the recently established Centre for Academic Writing (CAW) at the trilingual Free University of Bozen-Bolzano in northern Italy. The CAW was created in 2021 in response to a perceived need among academic staff for more writing support to be made available to students, as there was growing dissatisfaction with the work the latter produced, particularly in the form of the final thesis.

Although the CAW provides credit-bearing courses, these and the other services are offered on an entirely self-access basis, as none are obligatory. This paper will outline the services currently provided, explain the rationale for their implementation, and review how they have performed and been perceived since their introduction. There is a particular focus on the writing Helpdesks organised by the CAW, which offer students one-to-one support with a writing tutor. Since the activation of the Helpdesks, records of the queries received have been documented by the tutors and this paper presents an analysis of the kinds of queries received.

Literature Review

The concepts of learner autonomy, self-access, and self-directed learning highlight the importance of providing students with the tools and environment to be empowered to chart their own academic journey (see Knowles, 1975; Gardner & Miller, 1999), particularly at the tertiary level (Morrison, 2008). Learner autonomy is commonly defined as ‘the ability to take charge of one’s own learning’ (Holec, 1981, p. 3), and it is thus necessary to provide students with a certain degree of freedom to decide how to direct their learning. Learner autonomy is a capacity that can manifest in a variety of ways and behaviors, depending on the students’ age, progress, and perceptions of their learning needs (Little, 1991). As proposed by Nunan in his model, it “can be a normal, everyday addition to regular instruction” (1997, p. 201), which may mean that, for the students, this process could be integrated seamlessly into their day-to-day activities, either as part of their study plan, or with some dedicated sessions outside of class, in which students can choose freely their preferred learning activities and strategies.

Since the 1970s, the practical applications of these concepts have resulted in the implementation of self-access resources at universities and programmes aimed at fostering students’ autonomous learning processes (Little, 2015; Hobbs & Dofs, 2017; Reinders, 2013). Together with the proliferation of self-access centres (SACs) in the 1990s, these developments also led to a focus on self-directed learning (Benson, 2007). Self-directed learning (SDL) involves a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, to diagnose their learning needs, formulate goals, identify resources, choose and implement strategies, and evaluate learning outcomes (Knowles, 1975). SDL emphasizes the learner’s control over the entire learning process.

Self-access learning refers to the use of self-access centres (SACs) or resources designed to support independent learning. Gardner and Miller (1999) defined self-access language learning as a set of integrated elements that are combined to provide a learning environment where each learner interacts with these elements in a unique way. It differs from other types of self-directed learning in that it focuses on the learner’s interaction with situated facilities specifically designed for that purpose (Morrison, 2008). Although SACs aim to develop autonomy, self-access learning is not synonymous with autonomous learning (Reinders, 2013) because there is no direct link between the two, and there is no evidence that a self-access mode of learning will aid in the development of learner autonomy (Morrison, 2008). Nonetheless, it is evident that SACs exist to help self-access language learners grow their competencies and abilities as autonomous, independent, and self-directed learners (Morrison, 2008).

Recognizing students’ diverse needs and learning styles, SACs should provide a suitable location for them to find the resources they need and receive tailored support (McMurry et al., 2010; Mynard & Stevenson, 2017; Victori, 2007). Moreover, in addition to providing learning resources, they should represent a place where learners’ basic psychological needs are met, and their inner motivational resources are activated while promoting language learning (Mynard, 2022). The basic psychological needs, according to Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017), include:

- Autonomy: The need to feel in control of one’s own learning and actions

- Competence: The need to feel effective and capable of achieving desired outcomes

- Relatedness: The need to feel connected to others and experience a sense of belonging

A SAC should thus be envisioned as an environment that accommodates these needs (see Mynard, 2022), but also develops learners’ inner motivational resources such as curiosity, intrinsic goals, and interests (see Reeve, 2022), through the supply of engaging and relevant materials (e.g., online modules, writing guides, and language learning software), and by enabling students to set personal learning goals and pursue topics they find intriguing. Other ways may include the creation of an inviting and stimulating environment, collaborative spaces, peer tutoring programs, and study groups that build a sense of community and support among learners. Finally, provision can be made for feedback sessions, workshops, and exercises that help students develop their skills and track their progress.

Concerning academic writing, initiatives to increase autonomy often comprise modules, helpdesks, and comprehensive writing guides, provided either online or at the SAC, accessible to students at their convenience (see Andersson & Nakahashi, 2019; Victori, 2007). As a result, self-access resources can serve as valuable supplements to formal writing instruction, offering students additional support and personalized guidance as they deal with the challenges of academic writing. Universities can thus foster a culture of self-directed and autonomous learning through the use of self-access learning by providing students with opportunities to access resources based on their individual needs and schedules (Kongchan & Darasawang, 2015; Mynard, 2022; Reinders, 2013). This may enable students to develop skills beyond traditional classroom settings (cf. Benson, 2011) and may make them more inclined to continue their education outside of the classroom or to see a stronger link between their in-class and outside-of-class learning (Reinders, 2013).

The Centre of Academic Writing at the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano

The Free University of Bozen-Bolzano (unibz) is a multilingual institution situated in the bilingual (German – Italian) Autonomous Province of Bolzano – South Tyrol. Since its foundation in 1997, it has maintained a commitment to multilingualism and internationalization: unibz offers degree programs with lectures delivered in English, German, and Italian, in line with its plurilingual teaching model as stipulated in the university’s statute. The institution maintains stringent language entry and exit requirements for undergraduate degrees, mandating a B2 level in two languages upon entry, progressing to a B1 level in the third language by the second semester of the first year, and a C1 level in two languages and a B2 level in the third at graduation. Variations exist at the master’s level, with some faculties imposing slightly stricter requirements than at the undergraduate level, and others offering English-only degrees with admission requirements solely in that language. These language prerequisites are supported by the university Language Centre, which provides modular courses for all three languages. The composition of the academic staff also reflects this international outlook. As of 2022 – the most recently published figures – of the 826 tenured professors and researchers at unibz, 31% (256) have an international background. The university also boasts a notable presence of international students, accounting for 10.7% of the 4.374 students, exceeding the national average of 4.2%.

Although language proficiency at unibz is theoretically ensured through entrance and exit requirements, it became apparent that there was an increasing demand for specialized training for students in academic writing and communication. This need is distinct from the broader language support offered by the Language Centre. As a result, in 2021 a trilingual Centre for Academic Writing (CAW) was established at the Faculty of Education, which, with 1,445 students, is the largest faculty at the university. In addition to carrying out research on academic writing and communication in plurilingual contexts, the CAW offers a range of support options for students on a self-access basis to help them to improve their academic writing skills independently. One major area of activity is credit-bearing courses on academic writing in the three official languages and intensive programmes tailored for PhD students.

However, the mission of the CAW goes beyond merely teaching writing skills. The CAW aims to advance wellbeing and enable people to grow and thrive, and thus two additional services are offered: writing groups, and individual consultation services through Helpdesks. This paper will first outline these self-access services and will then provide a more detailed analysis of one particular service: the trilingual writing Helpdesks.

Courses

In the first two years, three 20-hour credit-bearing courses were offered for each language, aimed at BA- and MA-level students. The courses were held by a mix of faculty staff and adjunct professors, selected through the standard university recruitment procedure. No specific training was provided, but only tutors with significant experience in teaching academic writing were selected. Bi-yearly meetings are held with all tutors to discuss issues related to teaching and to coordinate the activities. As with all courses at the university, when enrolling for the exam, students must first complete an anonymous course evaluation form. The feedback received is used to inform the course offering in future years. Additionally, if feedback is generally negative, the course assignment for an individual tutor may not be renewed for the following academic year.

The courses offered in the first two years were named ‘Introduction to academic writing’, ‘Academic writing: intermediate level’ and ‘Academic writing: advanced level’, with equivalent names in the other languages. The courses were initially offered only to students in the Faculty of Education and were optional. The reason for the creation of three courses per language was to give students a clear learning path through the courses, enabling novice writers to progress from basic writing skills to thesis-writing skills in the advanced-level course. The precise contents of the courses depend on the language, but include types of academic text and text structure, academic style and register, paragraph structure and cohesion, summarising and paraphrasing, citations and references, formulating research questions, presenting data, and discussing results and implications.

Students were free to enrol on whichever course they preferred – no kind of entry test was carried out, although course tutors could be contacted for advice. However, considering the perceived need for support in academic writing, participation in the courses in the first year was disappointing. The faculty policy is for elective courses to be cancelled if attendance does not reach eight students in one of the first two classes, and for this reason some CAW courses had to be cancelled. As electives, the courses at CAW are essentially in competition with other (optional) courses and, naturally, students’ other commitments. When the same problem of low enrolments appeared to be occurring in the first semester of the second year, a focus group was held with student representatives to better understand students’ needs and their perceptions of the courses and of the Centre.

The focus groups raised a number of issues. One problem identified was the fact that students were confused by the course names and found it difficult to estimate what their ‘writing level’ was and thus which course they should enrol on. They also suggested that students might feel discouraged by the label ‘academic writing’, and particularly by the idea of ‘advanced academic writing’, feeling that such courses would be relevant only for those who were already competent writers when in reality the CAW was created primarily with students encountering difficulty with their writing in mind. The representatives suggested that functional names might make the aims of the courses clearer and would make them more attractive. Separately, course instructors had also expressed doubts about the length of the courses, suggesting that 20 hours of instruction (spread over approximately ten weeks) were not enough to allow the kind of independent writing work needed to adequately develop writing skills.

As a result of this, for the third year of the Centre’s activities, it was decided to both restructure and rename the courses. The concept of level was abandoned completely, and functional names were used instead. Instead of three 20-hour courses, two 30-hour courses for each language were created, called ‘Writing skills for university’ and ‘How to write a thesis’. The latter was implemented in the first semester, so that it could be completed before the main thesis writing period (which normally takes place in the second semester). The ‘writing skills for university’ course was programmed in the second semester. Since these changes were made, enrolments have improved, and all six courses (two per language) have been able to run consistently.

In addition to these six courses, an intensive course in academic writing English for PhD students, held by a visiting professor from the UK, is also offered just before the beginning of the academic year. There is no formal assessment for this course, but different PhD programmes choose to offer credit points for attendance on the course. End-of-course feedback is also collected for this course and has been positive. There have been requests from students to run a non-intensive version of the course at some point during the academic year.

Writing Groups

In addition to courses, the CAW organises a series of seminars, mainly aimed at staff and PhD students, with the aim of generating interest in the CAW, sharing perspectives, and generating ideas for the activities at the Centre. One such seminar explored the concept of writing groups and as there was interest in these among attendees of the seminar it was decided to pilot some writing groups at the Centre.

There is arguably not a strong tradition of writing support through language advising in Italian universities (see Bisset & Gödeke, 2015) nor at unibz. Yet in Italy, including at unibz, producing written work is, needless to say, a key competence for both students during their studies and academics during their careers. For students the problem is particularly acute as assessment across higher education in Italy is often conducted via means of oral examinations and in many courses, students may not need to write at all, or, when they do, may not be given specific or detailed instructions on how a text should be written. This means that when it comes to writing the most important text in their academic careers – the thesis – students tend not only to lack experience of writing to specific task instructions or assessment criteria, but they also may have only limited experience of the process of writing to draw on.

Writing groups and writing retreats have various theoretical and empirical underpinnings. For example, they have been linked to ‘Containment Theory’ (MacLeod et al., 2012; Murray et al., 2012), with writing groups seen as providing a framework for prioritising writing as the primary task while also ‘containing’ writing-related anxiety and anti-task behaviour. Research (e.g. McGrail et al., 2006; Morss & Murray, 2001) has also found that structured interventions such as writing groups are particularly effective in the context of academic writing. The activities associated with writing groups have been linked to the concept of ‘legitimate peripheral participation’ (LPP) within Communities of Practice theory (Lave & Wenger, 2011). LLP refers to the way newcomers become members of a community of practice by participating, initially on the periphery, in activities of that community. By participating, and observing more expert members of the community, newcomers (in the case of writing groups, students or early-career researchers) are gradually able to move from a position of peripherality to the Centre of a community of writers.

Two writing groups were created. One was open to academic staff and PhD students, and involved bi-monthly meetings online. For students, an in-person writing group was created to run in May–June, when students would be most busy writing their theses. It was publicised not as a ‘writing group’ but as a ‘writing social’, after Davenport (2022). This term reflects the ideal of transforming writing from an individual, hidden activity to one that can be carried out socially, and also the need to encourage social interaction during the restrictions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, which was in full swing when Davenport’s pilot programme first ran.

Both writing groups followed roughly the same pattern, a truncated version of the full writing retreat programme set out in Murray and Newton (2009). Each session contains three main steps, as follows:

- Setting/sharing writing goals: participants write a short, private text as a warm-up, in which they outline what they have already achieved in relation to their writing project and set specific aims for the current session. Following this, participants form small groups and orally share their goals for the session.

- Independent writing (typically 90 minutes)

- Reviewing writing goals: participants write a short, private text in which they reflect on whether they reached their goals for the session, and write their objectives for next time. They again review this orally in small groups.

The independent writing in this framework uses what Murray and Newton (2009) term a ‘typing pool model’, which means participants all writing together in the same room. In the case of the writing group for students, this means in the same physical room; for the online writing group, it means being present together in a virtual room on Microsoft Teams, with webcams switched on but microphones deactivated. This form of group writing has been shown – perhaps surprisingly to those who have not experienced it – not to create distractions but rather to develop a sense of a common purpose (Murray & Newton, 2009).

The writing groups were publicised by email, through student representatives and via posters. Attendees have given positive feedback but overall the level of interest, and hence participation, has been mixed, with only a handful of students attending. Writing groups are a virtually unknown concept in Italy and there are often misunderstandings among those who participate for the first time; for example, despite publicity materials clearly stating the nature of the groups, some participants arrive expecting to take part in some kind of class or workshop, to receive feedback on their work from a tutor, or to read one another’s work and give feedback. Given the strong theoretical and empirical foundation of writing groups as a form of self-access support, and the positive experience that members of CAW have had both as members and leaders of writing groups external to the university, the Centre is committed to persevering with and developing this service further. It is therefore planned to carry out consultations with both staff and student representatives to better understand how writing groups might be made as relevant and attractive as possible, to increase participation.

Helpdesks

The third service offered is the Helpdesk. It was decided to create a Helpdesk for each language that would enable students to receive prompt, personalised feedback for any problems or queries they had while writing during their studies. These were not intended to offer an alternative to the credit-bearing courses but were created in the knowledge that for many students, the availability of courses in academic writing would not be relevant when they had a specific, immediate problem while writing an assignment or their thesis. It was made clear from the beginning that the Helpdesk service could and would not offer a general proof-reading service, but that it would aim rather to provide responses to specific queries or problems. The service was publicised via emails sent to all students, communication with student representatives, and posters placed around the university building.

Helpdesk tutors are all adjunct professors, selected, as per the course tutors, via the university recruitment process. One of the helpdesk tutors currently also teaches one of CAW courses. As with the course tutors, no particular training is provided by the centre, but only tutors with significant experience teaching writing were recruited. The tutors also attend the bi-yearly meetings held with the course tutors in order to co-ordinate the activities of the centre. The first Helpdesk launched was for the German language. German-speaking students form the largest block in the Faculty of Education: at the time of writing, there are 865 L1 German speakers enrolled in the faculty, against 570 L1 Italian speakers. Given that students can choose in which language to write their thesis – which, for reasons outlined above, we expected to be the text that students would most likely need assistance with – the German language was prioritised. The German Helpdesk service began in Spring 2022 as a pilot, and was followed by the Helpdesks for Italian and English in late Winter 2022.

The Helpdesks are run completely online. Students make a booking autonomously using an online booking page and receive a link to the meeting (held via Microsoft Teams). Appointments are 30 minutes by default, but students may book two consecutive appointments if they feel this is necessary. After the meeting, students receive an automated email with a link to an online feedback page where they can express their level of satisfaction with the appointment. The three Helpdesk tutors (one for each language) keep a record of each appointment, choosing between five pre-determined query types and writing brief notes on it. The pre-determined query types are as follows:

- grammar (e.g. tense choice, morphology)

- vocabulary

- structure (e.g. overall text organisation, paragraph/section structure)

- citation / referencing (e.g. choice of reporting verb, paraphrase vs. direct quote, in-text citation style and reference lists)

- register (any language features dependent on context of academic writing)

One phenomenon observed was that, from time to time students wrote to the generic email address for the CAW with queries, or to ask if it was possible to request help from the CAW with some aspect of their writing. The initial practice was to reply, providing the link to the booking service and encouraging the student to make an appointment. Subsequent analysis, however, revealed that students who initially enquired in this way often did not make an appointment. This was puzzling as we had assumed that students would find it very convenient to be able to book an appointment online for an online video consultation using a platform – Microsoft Teams – with which they were very familiar. However, given that students were apparently choosing to initiate their consultation via email rather than by booking an appointment, it was decided to forward these inquiries to the tutors so that the consultation could take place by email, at least initially, rather than by the means of a video call.

Analysis of the Helpdesk Queries

As mentioned above, the nature of every enquiry received at the Helpdesks is recorded. This section presents an overview of the queries received so far, providing a snapshot of the difficulties students at unibz typically face.

Helpdesk in German

Students accessing the German writing Helpdesk were almost all L1 German speakers, with the exceptions of L1 Ladin speakers and some bilingual German-Italian speakers. The fact that most users of the service were native speakers is probably a reflection of the fact that nearly all students requiring help were doing so for their BA or MA thesis, which students can choose – and generally prefer – to write in their strongest language. Almost all students were from the Faculty of Education, where the Helpdesks are based and where communication with students about their existence is easiest to achieve. 120 queries were received, from a total of 83 different students.

Most students who use the German helpdesk consult the service once or twice, with very few exceptions. They usually ask for help when the thesis is already written but has been rejected by the supervisor. At this point, the text is generally of a good standard, with few errors in grammar, orthography or punctuation. Students are generally very motivated to produce a final, improved version of their text, and supervisors have often specified what exactly has to be improved to pass. When looking at the text with the Helpdesk tutor, it is not infrequent that a student proposes a solution spontaneously and without further help, simply by explaining in her/his own words the desired content. In such cases, the tutor’s task is limited to choosing the best wording, suggesting a slightly different order of ideas, and giving positive feedback. Although it is not the role of the Helpdesk to provide psychological counselling, students’ confidence in their ability to find a solution on their own often appears to suffer from negative feedback received from supervisors and from their previous attempts to remedy the situation without satisfactory results. Receiving positive feedback during a Helpdesk consultation (for example, on unproblematic parts of the text, the general structure, or the intellectual and scientific worth of the work done), and hearing that a member of academic staff (i.e. the Helpdesk tutor) recognises the effort of many months’ work often ‘unlocks’ the resources the student needs to overcome the final obstacles.

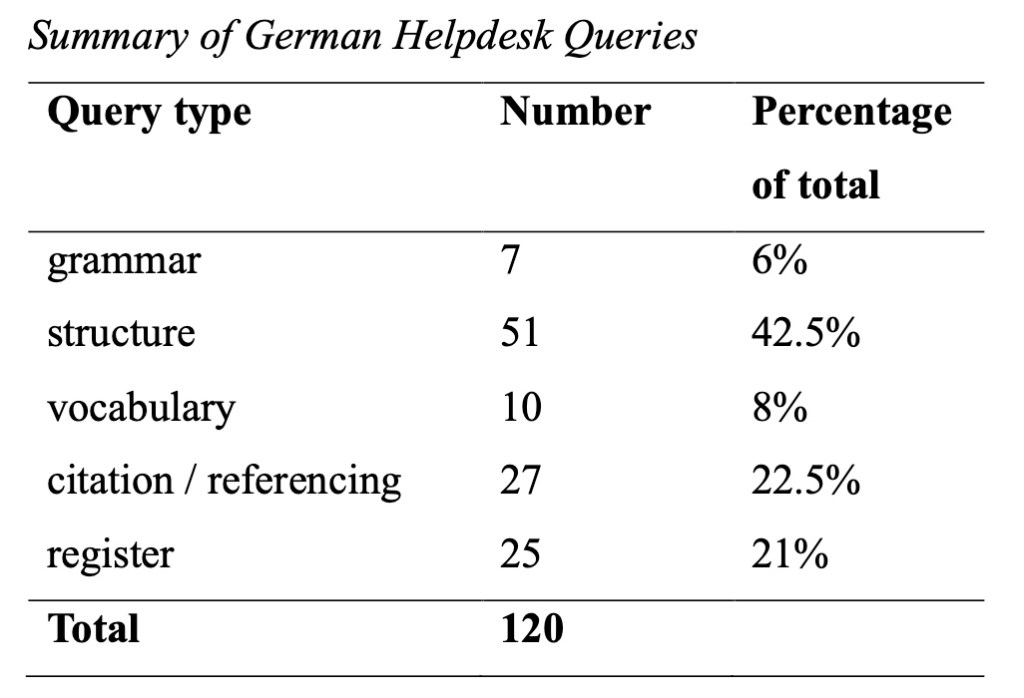

A summary of the queries received by the Helpdesk in German can be found in Table 1. As can be seen, queries received relate to a) grammar and vocabulary, b) register and citation/referencing, and, more frequently, c) the general structure of a scientific text. The order a) to c) roughly represents the complexity of the queries or the ‘advancedness’ of the students. Students with grammar or vocabulary issues tend to request help because of general negative feedback by professors (in this case, the students typically do not know exactly what is wrong), or because they have not managed to find a solution for particular sections of their text which have been criticised (because they either do not know what works or are double-checking with the tutor). As an example, one student accessed the Helpdesk with her thesis, the first three pages of which had been corrected by a supervisor with the instruction to continue correcting the rest of the text analogously. The analysis of the Helpdesk tutor was that the text was not incorrect, but that it contained repetitions, weak verbs and a lack of technical terminology, poor textual cohesion and did not appear to be particularly well planned out. Through her appointment with the Helpdesk, the student was empowered, both from a psychological and formative point of view, to work on and improve her thesis.

Table 1

Summary of German Helpdesk Queries

Students with register or citation/referencing issues usually have a list of relatively specific questions. These have included queries about secondary citations, how to find (better) sources, how to quote and how to formulate research questions. Some queries are sometimes quite unusual, for example how to cite a text from 400 BCE, or how to quote unorthodox sources. Students with these kinds of queries are generally satisfied with the answers to their questions and do not tend to need to access the Helpdesk on further occasions.

Finally, enquiries from students on general structuring often require a broader discussion on the scientific process and its translation into a text. The tutor may need to discuss themes such as: what is ‘result’ and what is ‘interpretation’? Is the method part of theory or part of practice? What to do when the findings during the course of a research completely change the view, in a way that the original research question becomes irrelevant and naive, while some other relevant answers appear? How to use non-text representations? Some students, however, are confronted with deeper problems, relating to meaning and logical structure. At this point, academic writing is not about grammar, register, vocabulary or structure anymore. In theory, what to write is the responsibility of students and, to a lesser extent, their instructors, and the Helpdesk plays a role when there are difficulties in how to write it. In this sense, ideas and their expression, and content and form, are neatly separated.. However, some of the texts the students bring to the Helpdesk tutor undeniably have problems of another type, relating to the layer between form and substance: specifically, the scientific method. A qualitative study with graphics presenting statistics on small numbers is such a problem: presenting the numbers prominently implies that the numbers prove something and that they are an important part of the argumentation, when they are not. Another example is inference problems: From an untrue hypothesis you cannot always infer that the contrary must be true. Logical fallacies, methodological errors or two hypotheses packed into a single one – these are examples of problems that are neither linguistic form nor subject content. Logic and the empirical method are an issue for some students, and discussions on this are often inspiring for the Helpdesk tutor and the student. In such cases, a ‘simple’ writing Helpdesk becomes involved in the philosophy of science, an essential component of university education.

Helpdesk in Italian

The students who used the Helpdesk service in Italian during the reference period are, like those who accessed the German Helpdesk, mainly enrolled in the Faculty of Education. They are in almost all cases, native Italian speakers (only one student was a native Chinese speaker). Forty-six percent of the sessions organized to support students were requested by students from the Bachelor’s Degree in Social Education, while 34% of the sessions were organized to assist students enrolled in the Master’s Degree in Primary Education. The remaining sessions were requested by students enrolled in the Bachelor’s Degree in Communication and Culture Sciences (9%) and in the Master’s Degree in Innovation and Research for Social, Assistance, and Educational Interventions (6%). In two cases, assistance was requested within different educational paths: within a doctoral program and within the Master’s Degree in Musicology.

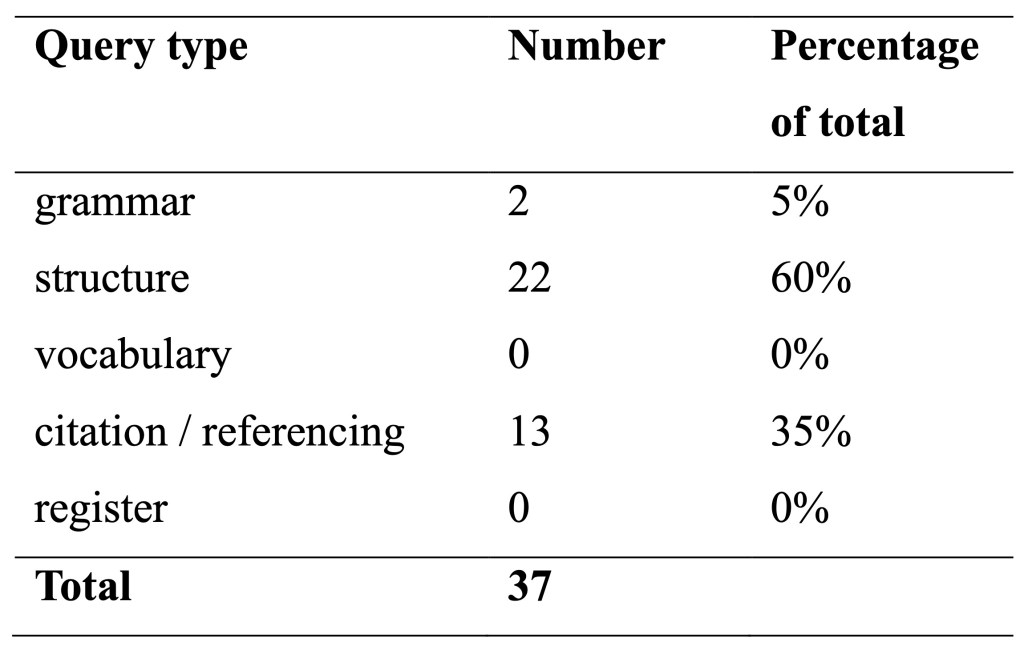

A total of 37 appointments at the Italian Helpdesk were carried out, by a total of 14 students. The majority of appointments were scheduled by students requesting follow-up sessions. 26 of the appointments were scheduled by six students. Furthermore, five students scheduled more than two appointments in order to be supported during the academic writing process. In this regard, it is interesting to note that there were two students who consistently (31% and 14% of the total amount of scheduled appointments) used the support service while drafting their thesis work. Unlike the German Helpdesk, students generally access the Italian Helpdesk because they have been advised to by their supervisor, but not because they have received overtly negative feedback.

Table 2 shows the queries received so far by the Helpdesk in Italian. As can be seen, fewer requests were received by the Italian Helpdesk compared to the German Helpdesk. This reflects in part the fact that, as explained above, the Italian Helpdesk was launched later than the German Helpdesk, but also the German-speaking students make up the majority in the Faculty of Education. A clear majority of requests (60%) concerned the structuring of academic writing, just as for the German Helpdesk. Enquiries of this type included issues such as how to plan a paper and how to develop its phases in an organic, structured way; how to structure the analysis of empirical data, including ways to show information using graphs and charts; and how to describe and analyse data deriving from interviews and questionnaires. A number of questions (35%) related to the methods to use for citing texts and/or for properly structuring the bibliography section. Only a minimal portion of students’ concerns pertained to the Italian language itself. This also represents another difference from the German Helpdesk, where, as mentioned, a far larger number of queries relating to vocabulary and grammar were reported, even though these were not among the most frequent.

Table 2

Summary of Italian Helpdesk Queries

Analysing the data collected, it becomes evident that the Italian Helpdesk service was almost exclusively utilized by native Italian-speaking students from the Faculty of Education, mostly towards the end of their academic journey and during the writing phase of their thesis. In this regard, it is not surprising that the type of requests was primarily oriented towards support on the specific textual type to be drafted, rather than on Italian writing proficiency. It is worth noting that students feel the need for constant support during the thesis writing process, support that complements the content-related guidance provided by the thesis advisor.

Helpdesk in English

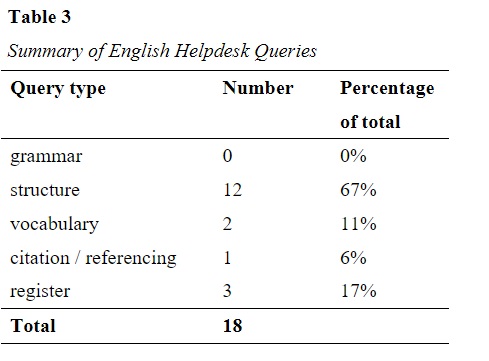

Since its implementation at the end of 2022, the English-language Helpdesk has primarily served Bachelor and Doctoral students in fields such as General Pedagogy and Computer Science. It is the least frequently used of the three Helpdesks. For the Faculty of Education – where the main ‘catchment area’ for the Helpdesks was always expected to be – this was not a surprise, since most students write their theses in Italian or German. Despite publicising the Helpdesks in other faculties, where writing a thesis in English is far more common, take-up has been relatively limited. The 18 appointments were made by four different students.

The query types for English can be found in Table 3. Common issues include paragraph structure, citation styles, and refining content to align with the genre-specific requirements. Queries often revolve around crafting academic writing thanks to the selection of the words pertaining to a formal register and appropriate and authoritative references. This is in contrast to the Helpdesks for German and Italian, and perhaps reflects a lower level of confidence towards register issues among students who write in English (which is only rarely the L1 for students at unibz). One of the participants has mostly requested advice on the structural elements of their thesis, including paragraph organisation. For instance, during one of the meetings, they sought advice on structuring the methodology chapter and where to place its sections. However, on other occasions, they inquired about language issues, such as which collocations are suitable for specific nouns and how to find synonyms for the verbs most commonly used to describe processes.

Table 3

Summary of English Helpdesk Queries

In contrast, bachelor students in Computer Science typically seek assistance with technical aspects of thesis writing, such as citation norms and structuring the content of their projects. Overall, the service provides tailored support for various academic needs, and its strengths lie in the personalised assistance it offers. However, challenges arise from the diverse writing styles across disciplines and the limited interest in English-language support due to the students’ preference for their native languages when writing their theses.

Discussion

Looking across the three Helpdesks, what is perhaps most apparent is that the most common types of query for each language were those related to structure. This of course does not necessarily mean structure of a whole text but can also relate to paragraph and section structure. As was noted in particular for the German Helpdesk, in some cases such queries even ‘bleed’ into somewhat wider areas relating to the scientific method in general. Following this, the most common query type related to citations. As explained, students often access the Helpdesk having received negative feedback from a thesis supervisor and, judging by the frequency of these queries, it is a combination of these macro-level (i.e. structure) and technical (i.e. citations) issues that cause students the most problems and/or create the greatest amount of dissatisfaction among supervisors.

As mentioned previously, the courses and Helpdesks at the Centre for Academic Writing are considered complementary services, but it is natural that they should also be mutually informative. One conclusion from the data collected at the Helpdesks might be to recommend that an even greater emphasis should be placed on structure within the syllabuses of the courses. However, all courses already include instruction on structure and given that they are optional (and thus only attended by a small majority of the total student body), it would not necessarily be the case that doing so would reduce the number of queries relating to this issue.

For this reason, in addition to continuing the one-to-one support for students currently offered by the Helpdesks, it also appears necessary to develop another form of self-access services: specifically, guides and handbooks. There is currently only very limited provision of such resources, and the CAW intends to expand this. The hope is that this would enable students to independently research their writing needs and, if necessary, address the Helpdesk tutor with well-focused and targeted questions related to their academic situation. However, the form of the information given is likely to be crucial and it may be the case that contemporary students at unibz are not particularly well disposed to (or used to) working through, for example, long PDF documents to find the information they need. Indeed, during the focus group discussed earlier, when the issue of self-access guides was being discussed one student representative mentioned that when she wanted to learn something new, her first search strategy was generally to search for a video on the topic on YouTube. For this reason, the Centre is currently exploring different forms which such guides could take, and a series of short videos covering issues related to structure and citations is being planned.

A further consideration at unibz relates to the rather unique sociolinguistic situation in which it operates. Lying at a cultural crossroads between German- and Italian-speaking areas, with the international language English also ‘thrown into the mix’, issues related to the appropriate advice to be given on academic writing are inherently complex. Unibz is an Italian university and must thus follow the national requirements of any other university in Italy. However, it operates in a predominantly German-speaking region and also possesses a highly international outlook, with English playing the role of an equal partner to the two local languages. This leads to a series of conundrums for the setting of writing standards. For example, should unibz look to German-speaking countries for norms on academic writing in German, or should standards relating to writing Italian be prioritised? A further option would be to look to standards in the English-speaking world for all three languages at unibz, but this would potentially risk creating a form of linguistic colonialism and the importation of Anglophone norms which are simply not particularly relevant to students in a very different context. These issues are discussed in some detail in Burton et al. (in press), particularly in relation to norms and standards for writing in English. They are likely to be particularly pertinent for self-access materials, which are accessed directly by students without the intervention of an instructor to discuss the nuances related to cross-cultural aspects of writing.

As for citations and references, we might speculate that such queries might become less frequent if students increasingly access what is perhaps the ‘ultimate’ self-access resource: artificial intelligence. It may be that Large-Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, or even relatively simple citation generators such as Scribbr, will be able to resolve most queries related to citations and references, just as the spell checker has resolved most orthographic errors. LLMs can already proof-read a text and provide feedback (both positive and negative) on it on request, although of course they can be notoriously unreliable in some aspects of academic writing (see, for example, Alkaissi & McFarlane, 2023; Lingard, 2023; McGowan et al., 2023). As LLMs become more widely known and more widely used, and perhaps also better trusted, it will be interesting to see if there is still demand for the Helpdesk service and the human contact which characterises it.

Conclusion

This paper has outlined the support currently offered on a self-access basis at the newly created Centre for Academic Writing at the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano. As a new unit, the CAW has had the advantage of not needing to follow an existing framework and has therefore been free to develop those resources that appear to be most needed by students. An analysis of the kinds of queries received by the Helpdesks reveals that students are most likely to choose to access this service when they have received some kind of negative feedback from their thesis supervisor and that their queries primarily relate to how to structure the thesis and, to a lesser extent, how to use citations and references appropriately.

At unibz, like many institutions, student attendance – if not enrolments as a whole – in classes has fallen since the Covid-19 pandemic. The CAW is no different and has often found itself in need of attracting students and encouraging students to use its services. A constant issue is how best to reach students, particularly those who are most likely to need support. As all services are offered on a self-access basis, there is no way to compel students to make use of the Centre. It is interesting that ‘traditional’ modes of communication with students (emails, posters) often do not seem to be the most effective – the Centre has sometimes had the greatest amount of success by contacting student representatives and asking them to share information on initiatives over social media, for example in WhatsApp groups. Additionally, the CAW now always has a presence at various introductory faculty and university-wide events for first-year students and prospective students, in order to inform students proactively about the services offered. In the short to medium term, the Centre will continue to consult with the university community in order to understand both which services and most needed, and the best ways to make them attractive and accessible to students.

Notes on the Contributors

Graham Burton is Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Education, Free-University of Bozen-Bolzano and a member of the scientific committee at the Centre for Academic Writing. His main research interests are corpus linguistics and its pedagogical applications, pedagogical grammar, writing for academic purposes and multilingualism / multilingual education.

Elena Borsetto received her Ph.D. in Educational Linguistics from Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Italy, with a study focusing on the vehicular use of English in higher education. She is currently conducting post-doctoral research at the University of Verona on a project related to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). She works as a teacher trainer in professional development courses for academic staff, as a language tutor for the Center for Academic Writing (CAW) at the Free University of Bozen/Bolzano, and as an English lecturer.

Leonhard Voltmer (LL.M., Ph.D. in Linguistics and Law) is the tutor for the German Helpdesk at the Centre for Academic Writing, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano.

Alessandra Giglio (PhD in Languages, Cultures and Technologies) is a lecturer at the University of Dalarna, and Adjunct Professor and Academic Tutor for the Italian Writing Support Desk at the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano.

References

Alkaissi, H., & McFarlane, S. I. (2023). Artificial hallucinations in ChatGPT: Implications in scientific writing. Cureus, 15(2), e35179. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.35179

Andersson, S., & Nakahashi, M. (2019). Establishing online synchronous support for self-access language learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 10(4), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.37237/100402

Benson, P. (2007). Autonomy in language teaching and learning. Language Teaching, 40(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444806003958

Benson, P. (2011). Language learning and teaching beyond the classroom: An introduction to the field. In P. Benson & H. Reinders (Eds.), Beyond the language classroom (pp. 7–16). Palgrave Macmillan.

Bisset, M., & Gödeke, B. (2015). Integrated learner support through language advising: Initial experiences and considerations at Padova University Language Centre. Language Learning in Higher Education, 5(2), 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1515/cercles-2015-0020

Burton, G., Lazzeretti, C., & Gatti, M. C. (in press). EAP teaching and learning in a multilingual context: Challenges and implications. Textus.

Davenport, E. (2022). The writing social: Identifying with academic writing practices amongst undergraduate students. Investigations in University Teaching and Learning, 13, 1–7.

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

Hobbs, M., & Dofs, K. (2017). Self-access centre and autonomous learning management: Where are we now and where are we going? Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 88–101. https://doi.org/10.37237/080203

Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy and foreign language learning. Pergamon.

Kongchan, C., & Darasawang, P. (2015). Roles of self-access centres in the success of language learning. In P. Darasawang & H. Reinders (Eds.), Innovation in language learning and teaching: The case of Thailand (pp. 76–88). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137449757_6

Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Follett.

Lave, J., & Wenger, É. (2011). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Lingard, L. (2023). Writing with ChatGPT: An illustration of its capacity, limitations & implications for academic writers. Perspectives on Medical Education, 12(1), 26–270. https://doi.org/10.5334/pme.1072

Little, D. (1991). Learner autonomy 1: Definitions, issues and problems. Authentik.

Little, D. (2015) University language centres, self-access learning and learner autonomy. Recherche et pratiques pédagogiques en langues, 34(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.4000/apliut.5008

MacLeod, I., Steckley, L., & Murray, R. (2012). Time is not enough: Promoting strategic engagement with writing for publication. Studies in Higher Education, 37(6), 641-654. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.527934

McGowan, A., Gui, Y., Dobbs, M., Shuster, S., Cotter, M., Selloni, A., Goodman, M., Srivastava, A., Cecchi, G. A., & Corcoran, C. M. (2023). ChatGPT and Bard exhibit spontaneous citation fabrication during psychiatry literature search. Psychiatry Research, 326, 115334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115334

McGrail, M. R., Rickard, C. M., & Jones, R. (2006). Publish or perish: A systematic review of interventions to increase academic publication rates. Higher Education Research & Development, 25(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360500453053

McMurry, B, L., Tanner, M. W., & Anderson, N. J. (2010). Self-access centers: Maximizing learners’ access to center resources. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(2), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.37237/010204

Morrison, B. (2008). The role of the self-access centre in the tertiary language learning process. System, 36(2), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2007.10.004

Morss, K., & Murray, R. (2001). Researching academic writing within a structured programme: Insights and outcomes. Studies in Higher Education, 26(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070020030706

Murray, R., & Newton, M. (2009). Writing retreat as structured intervention: Margin or mainstream? Higher Education Research & Development, 28(5), 541–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360903154126

Murray, R., Steckley, L., & MacLeod, I. (2012). Research leadership in writing for publication: A theoretical framework. British Educational Research Journal, 38(5), 765–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2011.580049

Mynard, J. (2022). Reimagining the self-access centre as a place to thrive. In J. Mynard & S. Shelton-Strong (Eds.), Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom: A self-determination theory perspective (pp. 224–241). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788929059-015

Mynard, J., & Stevenson, R. (2017). Promoting learner autonomy and self-directed learning: The evolution of a SALC curriculum. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.37237/080209

Nunan, D. (1997). Designing and adapting materials to encourage learner autonomy. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 192–203). Longman.

Reeve, J. (2022). A brief but comprehensive overview of self-determination theory. In J. Mynard & S. Shelton-Strong (Eds.), Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom: A self-determination theory perspective (pp. 13–30). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788929059-015

Reinders, H. (2013). Self-access and independent learning centres. In C. Chapelle (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal1059

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017) Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press.

Victori, M. (2007). The development of learners’ support mechanisms in a self-access center and their implementation in a credit-based self-directed learning program. System, 35(1), 10–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2006.10.005