Lesley Adams, Language Centre, University of Padova, Padova, Italy

Erik Gasparini, Department of Biomedical Science, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy

Adams, L., & Gasparini, E. (2024). Learning from good learners: A case study. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(2), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.37237/150207

Abstract

This paper describes how motivation, goal-setting and autonomous study can lead to the achievement of objectives in language learning and certification. The learning journey reported was documented through interviews and written accounts received from the research participant. The results achieved and the description of the process might be useful for students and also for teachers and learning advisors wishing to encourage autonomy and reflection in their students.

Keywords : learner autonomy, successful learners, motivation

In recent years in Italy, it has become ever more necessary to achieve a high band in IELTS (International English Language Testing System), both for study and for work requirements. It is now a high-stakes test, for which students and graduates in all disciplines are applying their study skills to obtain the required result.

The desire to write this article stemmed from an encounter with a particularly industrious and motivated student, Erik (the second author), who attended an IELTS preparation course taught by me, Lesley (the first author), at the University of Padova, and who obtained a result over and above his expectations. My aim was to use Erik’s input in order to garner information on successful self-study when preparing for an exam, and to make use of this to help students on future exam preparation courses. In this article, I will report on the results of a questionnaire and an interview carried out with Erik in order to gather information on how he prepared for the exam and achieved his aims . I will also provide a brief summary of Erik’s written account of his journey, the full version of which is contained in Appendix 1.

Background

I have been an EFL teacher for 30 years now and am also involved in the assessment of international written and spoken exams. For many years, I taught students how to pass the various levels of Cambridge main suite exams, from A2 Key to C2 Proficiency,[1] but until this year, I had little familiarity with IELTS, apart from a short time in 2020 when I was an IELTS speaking examiner, and a few lessons coaching an individual student in 2022. I have tended to avoid taking on teaching IELTS preparation courses, mainly due to the fact that Writing Task 1 (where test-takers have to write a summary of data, such as one or more graphs) does not appeal to my rather non-scientific mind. However, there are now more than 70 centres around Italy, where IELTS can be taken,[2] and one of these is the University of Padova, where I have been working as a Language Collaborator for the last three years. In September 2023, I was given my first group to prepare for the IELTS exam.

Research Setting and Participant

The course was an intensive face-to-face course of a total of 24 hours, running from 11th-27th September, and divided into eight lessons of 2.5 hours. I chose to give the students a 15-minute break approximately halfway through the lesson, as, in my view, frequent breaks are important to maintain concentration. There were 16 students, all young adults apart from one university lecturer.

Although I had done my best to familiarize myself with the content of the exam in the few weeks available before the course began, during the first lesson, I became immediately aware that there was a student in the class who had worked harder than me in this respect. None of the students had taken IELTS before, and 15 of them knew practically nothing about it. Erik, however, was evidently extremely well-informed, and his exam date was already booked for two days after the end of the course.

Erik has a three-year degree and a two-year Master’s degree in Biomedical Engineering, so he was clearly not new to studying. He now needed a Band 7 in IELTS (equivalent to C1 on the CEFR) in order to begin his Ph.D. at the University of Pisa in October. As he told me, when he had begun to study for IELTS he was quite far from achieving this band, scoring a 5.5 in the first mock tests he tried. However, during the course, from what I could see, his general level was a Band 6/6.5, so he had clearly already made improvements.

At the end of the course, I asked Erik about the studies he had done beforehand, and he replied that he had studied approximately 12 hours a day every day for at least two weeks. It was at this point that the idea of using him as a model for self-study began to form.

I asked Erik to let me know his results when they came through, and in a short time, he emailed me to inform me that he had obtained a Band 8. This exceeded his expectations and the requirements of the University of Pisa, and he was delighted with the result. He agreed to have an interview online to discuss his progress, and a few days before I emailed him the questions I had planned to ask him (see Figure 1). In reply, I received a detailed account. (See Appendix My Exam Journey.)

My Aims

Erik had clearly shown evidence of being a successful learner. Two factors that are generally considered important in successful language learning are motivation and learner autonomy. We already know that Erik was highly motivated; to use the terms coined by Gardner and Lambert (1972), his motivation was instrumental (related to a goal) rather than integrative (for his own personal satisfaction). Dörnyei (1998) states that motivation is the driving force to sustain the long and often tedious learning process. Erik had also already demonstrated aspects of successful learner autonomy, which, for Mynard (2019), involves individualizing the learning process, including managing the content, pace, strategies, and resources. My research questions were therefore:

- Which methods had Erik employed to help him achieve his objective?

- Would he be able to provide tips or strategies which I could then pass on to students in future courses to help them to succeed?

My secondary aim, or interest, was to find out whether Erik considered his general level of English had improved as a result of his exam-focused studies.

Methodology

The methodology employed was that of a case study. Stake (2008, p. xi) defines this as “the study of the particularity and complexity of the particular case, coming to understand its activity within important circumstances.” Multiple data sources were employed.

– A narrative analysis in the form of Erik’s own written account based on the prompts and questions I sent him. This was written in English and sent to me some days before we had our Zoom meeting. I made some minor language corrections and then sent it back to him, asking him to read it and confirm my interpretation of a few highlighted points.

– A follow-up interview to clarify and expand on the details provided in Erik’s account. The interview was held in English and recorded. I then listened to it again in order to extract any important information not present in the written account.

Figure 1

Questions Sent to Erik

- Were you aware of your learning style before you started studying for this exam? Had you ever done a learning style test?

- Do you think you are a visual, auditory, kinaesthetic or analytical learner?

- Were you consciously aware of the strategies you were using during your studies?

- What is your educational background?

- Did you employ techniques and strategies for this exam that you had already used for previous studies (in other subjects)?

- How did you identify which resources to use?

- How did you assess your progress?

- In what ways did the 24-hour course help you further?

- How was your mood over the weeks while you were studying? Did you consciously try to feel positive, and did this help you to study better?

Apart from your excellent exam result, do you feel your level of English has improved in general?

Can you write an account of how you studied for this exam? Starting with your first level test, the plan you made, and what you did every day, how many hours, breaks, etc.?

Findings

Erik’s Story

The Appendix, My Exam Journey, gives a detailed account of the strategies and skills Erik applied in order to achieve his goal. One of these is discipline, which can be seen throughout the six-month period he describes, particularly in the rigid schedule he sets himself in the three weeks leading up to the exam on September 30th. Another strategy he employs is setting out to learn in the way he knows is most successful for him: taking written notes. It is also evident how he continues to reflect on his learning and to adapt his plan accordingly. For instance, in Stockholm, he notices how external constraints are hindering him (time available, lack of suitable opportunities to practise the specific type of speaking skills needed for IELTS, etc.). He is also able to assess his learning tools and make changes accordingly, such as when he decides that Duolingo is unsuitable for his purposes.

Taking a mock test brings Erik to some more useful reflections. He realises he needs to build up his physical stamina in order to be able to take the complete test without breaks and obtain a good score, to work on what the mock test has shown him are his weak areas, and to discover more about the way IELTS is assessed. At this point, he enlists the help of a proficient English speaker and enrols on Padova University’s IELTS preparation course. At the same time, he continues to employ self-study skills by learning the phonemic chart alone and beginning to record the pronunciation of new words and expressions.

Zoom Interview with Erik

Four main points of interest emerged from the interview. The first was Erik’s answer to question 1 of my questionnaire about learning styles (see Figure 1). He reported that, although the result of a learning style test done some years previously had been that Erik was a visual learner, he subsequently found through experience and reflection that images were not sufficient for him to learn well. Consequently, during high school, he tried new techniques and styles and discovered that he was more a kineasthetic learner and that he needed to write a lot in order to memorise things, especially, for example, expressions and equations. When asked, he also emphasised that he had a strong preference for writing things down by hand rather than on a computer. These details demonstrate that Erik had previously established how he learnt best in subjects other than languages by experimenting and reflecting, and through his account in the Appendix we learn that he transferred this knowledge to his IELTS-related studies.

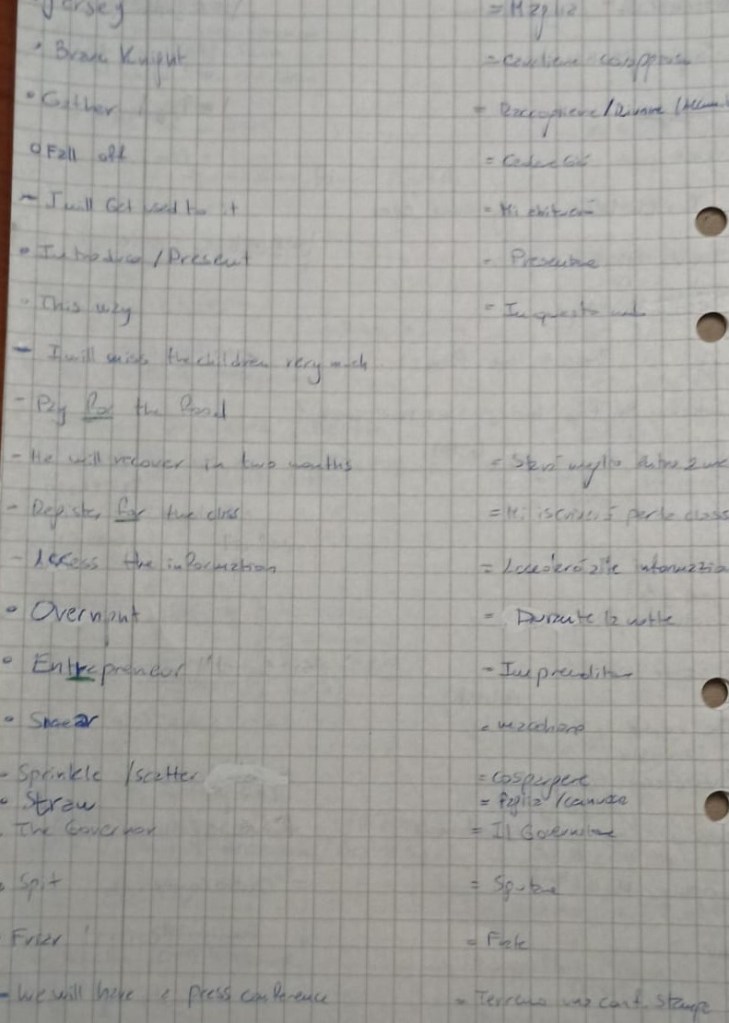

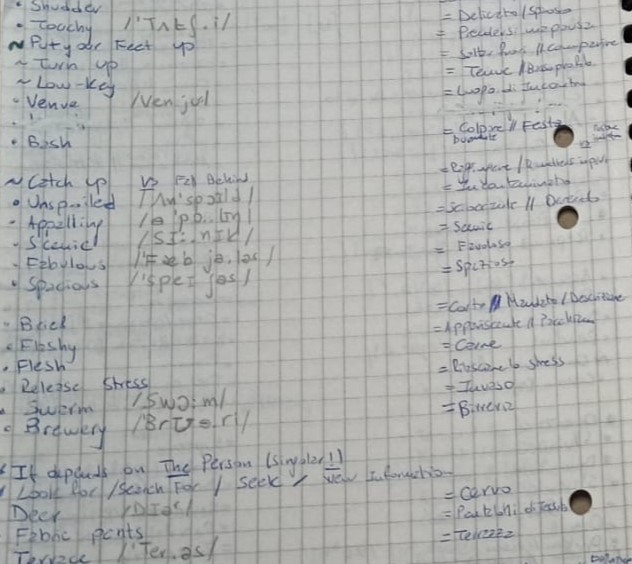

The second point that struck me as significant was that Erik, on several occasions, mentions his “booklet,” which was basically a notebook where he physically wrote down words he did not know while reading (first in his own field of study, then from newspapers and later from specific IELTS exam material) and where he later began to add synonyms, collocations and the pronunciation in phonemic script. He clearly considers this notebook as being important for his progress. What was also remarkable from my point of view was that at first, he was only recording the new words and their translation in Italian (see Figure 2 ), but during his journey, he came across phonemic script and realized that it could be useful to him. This discovery led him to the realization that he had been mispronouncing some common words for many years (he gives the example of the word “money”). At this point, he began adding the phonemic script to the new items of lexis he was recording in his notebook (see Figure 3).

The third point of interest was represented by Erik’s thoughts on assessment, both self and external. He explained that, in his view, general improvement can be self-assessed simply by realising that one is understanding more when reading and speaking. However, assessing improvement in specific exam skills is much harder, in particular for writing and speaking. He pointed out that his level in Listening and Reading for IELTS could be self-assessed by doing mock tests on the Internet but that neither AI nor friends with a good level of English were useful to assess his writing and speaking skills for the exam, as in this case he really needed someone who was an expert on IELTS and its assessment criteria. His first mock test under exam conditions was a turning point for him, as the result was low, and he realized he needed to change something in his study plan. His opinion was that his efforts until then had led to an improvement in his general level of English, but his specific IELTS exam skills had not improved significantly. He, therefore, believes that mock tests are fundamental for students preparing for IELTS, as they allow them to understand their current level and weak areas. He thinks students should do a complete mock test at least 4-6 weeks before they intend to sit the exam. If students are going to do an IELTS course, they should either have already tried the mock test before they begin the course, or they should do one halfway through the course. The course itself provided the expert assessment Erik had been lacking for his IELTS writing and speaking skills.

The final aspect that emerged from the interview regards point 3 in the section My Aims: Did Erik believe his general level of English had improved as a result of his intensive exam study? As specified above, after taking his first mock test, he felt that his first period of study was not focused enough and that his general level of English had improved, but not his specific IELTS exam skills. But how did he feel now that the exam was over? Erik told me that he believed some general skills such as fluency had improved, and also some soft skills such as confidence when speaking English. However, due to the specific nature of the exam, his belief is that many of the skills learnt are specific to IELTS and did not lead to an improvement in his general level of English.

Figure 2

Erik’s Notebook at the Beginning of Study Plan

Figure 3

Erik’s Notebook After he Started Recording Pronunciation of Words in Phonemic Script

Conclusions and Future Plans

At the beginning of this article, I pointed out that we already knew that Erik was a motivated and autonomous learner. I believe his account of his exam journey and his recorded interview show that he fits the description of a reflective learner as someone who employs “the process of thinking deeply about one’s language learning in order to understand the processes to take informed and self-regulated action towards language outcomes” (Mynard et al., 2023, p. 4). It could be useful for other students to read his account and see how being a methodical and reflective learner helped him to achieve his aims. I believe that my encounter with Erik will help me to provide several new tips and ideas for autonomous study to my future students. It is extremely useful for teachers to have information from students about the exam day itself, as this is something teachers will not experience for themselves. In this regard, I have begun sharing Erik’s strategy of preparing by doing full mock tests within the time limits given on the actual test day in order to build up stamina for the test itself since the IELTS test is quite long and tiring, as there are no breaks between the components. I will also take into account his views on the importance of mock tests, which I already shared, but my courses until now have been quite short, so I decided there was no time to include one. He also found the British Council site[3] very useful; this was already included in the Useful Resources section of my Moodle course, but I will stress its importance with future students.

Another strategy which I will share is how Erik found it useful to learn something about phonemics. I have always been very interested in pronunciation, regularly showing my students a phonemic chart to illustrate a pronunciation point. In my IELTS course, I had already focused on intonation, contrastive stress, and other features of pronunciation to improve speaking scores. Until I had the interview with Erik, however, I had considered it excessive to expect students to learn phonemic script. Now, I plan to add a phonemic chart to the Useful Resources section of my next IELTS course and to explain to my students how Erik used it to record and remember the pronunciation of new items of vocabulary. Lastly, in addition to my own Resources section on my IELTS Moodle, I intend to add a section called Tips from previous students, and ask students to upload accounts of how they prepared for IELTS. Hopefully, this will encourage more learner autonomy in all my future students and provide them with relatable experiences to do as well as possible in the exam.

This study gave me a detailed insight into the way Erik had prepared for his exam. It showed that being methodical, reflective and discovering and focusing on his preferred learning style and weak points helped him to be successful. It also clarified what he felt were the elements that could only be provided by a teacher: assessment and correction of his written and oral abilities specific to the IELTS test. This confirmed my own beliefs about what it is most useful to focus on in IELTS courses. It is hoped these points will be useful to other teachers working in my field.

Erik was not convinced that the progress he made in specific exam-based skills improved his general level of English. This belief was based on self-assessment and is the opinion of one student. Further research in this area carried out on a larger group of participants, or on participants preparing for other international language certifications, might be interesting.

Notes on the Contributors

Lesley Adams is a DELTA-qualified EFL teacher, teacher trainer and English Language Assessment Specialist. She holds a B.A. (Hons.) from the University of Bristol, UK and works as an English Language Expert and Collaborator at the University of Padova.

Erik Gasparini has a B.Sc. in Biomedical Engineering and an M.Sc. in Bioengineering from the University of Padova and is currently undertaking a Ph.D. in Biorobotics at the University of Pisa.

References

Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Language Teaching, 31, 117–135. http://doi.org/10.1017/S026144480001315X

Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second-language learning. Newbury House Publishers.

Mynard, J. (2019). Advising and self-access learning: Promoting language learner autonomy beyond the classroom. In H. Reinders, S. Ryan, & S. Nakamura (Eds.) Innovations in language learning and teaching: The case of Japan (pp. 185–220). Palgrave Macmillan https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12567-7_10

Mynard, J., Curry, N., & Lyon, P. (2023). Promoting reflection on language learning: Introduction. In N. Curry, P. Lyon, & J. Mynard (Eds.), Promoting reflection on language learning: Lessons from a university setting (pp. 3–12). Multilingual Matters.

Stake, R. E. (2008). The art of case study research. Sage Publications.

[1] https://www.cambridgeenglish.org/it/

[2] https://www.ielts-writing.info/EXAM/test-center-search/italy

[3] https://www.britishcouncil.it/

Appendix

My Exam Journey by Erik G.

My exam journey can be divided into three temporal periods: the first in March, the second in August and the last in September (I eventually took the exam on September 30th).

March – Erasmus+ Period in Stockholm

I first had the idea of taking the IELTS exam in March because I was doing my Master’s thesis in Stockholm, and I used English every day to communicate with Swedish and international students. Therefore, I started collecting information related to this exam (the format, the available dates, etc) and reliable sources for preparation. Following one of the tips I found on the British Council site, I started taking notes in a booklet of all the unknown words I encountered and their meaning. At the same time, I began working on each specific area as follows:

– Listening: BBC and TED podcasts while commuting to the University – 45 minutes in the morning and 45 minutes in the evening).

– Reading: Some papers related to my thesis and general articles (The Times, The Conversation) – approximately 1 hour in the morning.

– Writing: Some summaries of articles/audio broadcasts – approximately half an hour a day.

– Speaking: Everyday conversation with people – undefined time.

I also tried some popular apps such as Duolingo, but their content was extremely repetitive and unsuitable for reaching the higher bands.

Although it was generally a promising plan, I found some issues:

- Due to the time I was having to spend on my thesis, the effort I would have liked to dedicate to this study was not constant.

- It was impossible to have objective assessments of my writing and speaking skills (the latter because in everyday conversations people do not usually correct your mistakes).

- he type of conversations I encountered in daily life were very different from the speaking part of the test.

Therefore, I decided not to take the exam in Stockholm as I did not feel I was ready.

August- General Advanced English University Course

In August, I applied for a PhD course that required me to have by October an average IELTS band of 7 and at least 6.5 in each component. Therefore, I started to study for the exam again. It was summer holiday time, so I used to dedicate just a few hours per day to it (listening to some podcasts, watching some movies and reading some English books). I also enrolled on a 3-week non-IELTS-related advanced English university course (3 hours per day in the morning). Although this was useful for revising some grammatical structures, I felt it was not appropriate for the exam (we did not do any writing and the other students were not motivated to practice the language).

To test my level, I booked a free mock test (in the exam centre where I would later do the exam, under exam conditions). I found myself completely unprepared for the physical effort that this required (I had never practised all the components without a break) and the final mark I received was 5/5.5 (so much lower than my expectations).

As a result of this, I realised that I was lacking in the following areas:

- I had no clear understanding of the assessment criteria (for example the importance of pronunciation in the speaking part or the relevance of synonyms).

- I had never practised speaking to a physical person (I used to record myself, without considering the mental effort of speaking to a real person).

- I had never tried a complete mock exam without breaks.

- Until now I had been distributing my effort equally between the different parts of the exam, without considering which areas I was most lacking in.

- I had never received feedback from an expert on the writing and speaking part (AI sources were not knowledgeable enough about assessment criteria for the exam, and my fellow students had a similar level of English to my own).

September- Specific IELTS University Course

As a consequence of the above considerations, I modified my study plan to include the following objectives:

- Understanding the assessment criteria by watching IELTS and British Council videos, and beginning to record the pronunciation and synonyms along with the new words in my booklet as previously mentioned.

- Practising speaking every day with a friend. On YouTube there are many examples of IELTS speaking questions; the other person (whose English was a better level than mine) asked me these questions and listened to my answers and also corrected me.

- Practicing writing and speaking even when I was exhausted.

- Focusing more on speaking and writing (which were the areas where I was weaker).

- Enrolling on the University 24-hour IELTS preparation course.

This course was useful because:

– I received proper assessments of the writing and speaking part from an English native speaker teacher.

– The book used for the course contained 6 complete exams (useful for understanding the similarities and differences among them).

– I was in a motivated environment in which people gave clear and constructive feedback.

In particular, as I needed to progress from the Band 5.5 I had received in my mock test to the required Band 7, I devised the following daily routine for the three weeks during which I was attending the course at University (7/7 days):

– 7:00-8:00: Breakfast + Podcast.

– 8:00-10:30: Repetition of the new vocabulary in my booklet (+pronunciation and synonyms).

– 10:30-12:30: Lesson.

– 12:30-13:30: Lunch

– 13:30-15:30: Listening/Writing exercises from the British Council site.

– 15:30-16:00: Break.

– 16:00-18:00: Speaking with a person.

– 18:30-20:00: Dinner + Podcast.

The program changed in the final week because I started doing one complete test per day, so it became:

– 7:00-8:00: Breakfast + Podcast.

– 8:00-10:30: Repetition of the new vocabulary in my booklet (+pronunciation and synonyms).

– 10:30-12:30: Lesson.

– 12:30-13:30: Lunch

– 13:30-16:30: Mock test

– 16:30-17:00: Break.

– 17:00-18:00: Speaking with a person.

– 18:30-20:00: Dinner + Podcast.

– 21:00-22:00: Speaking with a person.