Joshua Lee Solomon, Institute for the Promotion of Higher Education, Hirosaki University, Japan

Solomon, J. L. (2024). SALC as a community: Perspectives on heavy-recurrent users. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(4), 396–419. https://doi.org/10.37237/150403

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is first to develop a more complex understanding of students in the English Lounge, a self-access learning center (SALC) in northern Japan, by applying a sociological lens to their actions and experiences. The impetus for this project came from the desire, based on both personal experience and by analyzing sign-in data, to consider SALC users as a multiplicity rather than a monolith. While much energy has been expended at this institution toward addressing the needs of the broadest profile—that of the completely, or near-completely disengaged user—there is also potential for learning from the most extreme cases of heavy-recurrent users. Also, while the institution assumes that the primary beneficiaries of the SALC’s resources are Japanese undergraduates, the facility is a more complex organism with a variety of stakeholders. Thus, in addition to surveying heavy-recurrent users’ motivational histories, images of the SALC, and patterns of use, this paper also incorporates the results of a small-scale survey of international students hired to work as conversation partners. Keywords: student-led language learning community, autonomy-supportive leadership development, reflective practice

Keywords: student-led language learning community, autonomy-supportive leadership development, reflective practice

There is a peculiar alchemy formed within the walls of the self-access learning center (SALC) whereby some visitors gain, longitudinally, valuable and motivating—veritably golden—experiences on the one hand, whereas so many others seem to leave with leaden lumps of frustration for their efforts on the other. As there is an implicit or explicit mandate at any institution with a SALC to attract and retain as many users as possible (thereby boosting easily understandable quantitative metrics of engagement), faculty discussions about SALC management tend to revolve around rejiggering various push and pull incentives aimed at disengaged users. At Hirosaki University, Japan, this impulse has recently been boosted by a reinforced relationship between our SALC (the “English Lounge”) and the new liberal arts English curriculum implemented in the 2023 academic year (Tatsuta, 2023). Because our learning center does not offer grades, credit, certification, or other obvious metrics of “success,” our ability to draw in more users and convert them into recurrent users has been used as the default, most direct method of articulating the facility’s achievement—and justifying its continued existence—to the rest of the institution. As students who visit the SALC only once or twice a semester comprise between 60%–70% of the user base in a given year (Solomon, 2024, p. 64), the planning of events or activities to entice any number of them to return could have substantial outcomes for the facility’s overall profile, at least quantitatively. It is true that internal observations and data suggest that not all low-frequency users are disinterested in accessing the space; rather, they report a lack of awareness of how to utilize the facility or low levels of confidence in their English abilities and may be cowed by the presence of advanced-level English users and foreign students in the space, creating a significant hurdle for them visiting of their own volition or returning after their initial, sometimes harrowing, experience. These are serious concerns, that as facility managers, we cannot ignore. At the same time, a myopic focus on the lowest-frequency users ignores the reality of the SALC and the various users who comprise the core of its community. It is this diverse core of the Hirosaki University English Lounge, rather than its fringes, who are the primary subject of the following pages.

The present study combines a theoretical framework from the fields of sociology and literary studies with secondary research on identity and second-language learning and the results of two small-scale surveys, one conducted with heavy-recurrent users of the English Lounge and the other with international student “supporters” in the space. As the study developed, “community” arose as a through-line, tying each of these elements together. The following section lays out the groundwork for the rest of the paper by theorizing community and how it may apply to the case of SALCs.

Theory of SALC as Community

Drawing on first-hand experience working in the English Lounge, I began by hypothesizing that SALCs have the potential to provide the opportunity for community creation in a very real sense. There is significant precedent for viewing learning centers and schools in terms of community. Learning spaces in general, and SALCs in particular, have been theorized using the language of “learning communities,” “social learning spaces,” “community of language learners,” “international communities,” and especially “communities of practice,” where the concept of community is deeply intertwined with identity. A community of practice is defined by a shared domain (interest or competence), community (social interaction), and practice (sharing of knowledge and skills) (Wenger-Trayner, 2015). Community membership and status are deeply intertwined with issues of identity. Mynard (2020) examines the relationship between learner identity and SALC usage, finding that “reflexive identity” (self-image)—including a dissonance between one’s reflexive identity and the perceived identity of SALC users—to be a significant factor in learners’ decisions to use the space or not.

Shibata (2016) describes using low-stakes extensive reading assignments to cultivate learner identities within a community of practice, effectively acclimatizing students to the SALC space through gradual identity formation. Another study analyzes SALC communities of practice from the standpoint of engagement (creating an accessible environment), imagination (community-member role modeling), and alignment (conforming or adapting to community goals) (Hooper, 2020). Such studies tend to focus on the construction of community participant identity under the assumption that the SALC functions primarily as a community of learners.

I do not dispute that the English Lounge is a community of learners (or a community of practice) but hypothesize that it serves additionally as a generative social community which serves its participants in ways that exceed its stated goal as an institution of language learning. As Hirosaki University is located in a smaller provincial city with a much less diverse local population and fewer opportunities to encounter and use non-Japanese languages than in its counterparts in larger metropolitan areas, the potential for intercultural exchange between Japanese and international students, as well as intracultural exchange between these same groups, is a critical aspect of its existence. With conversation, active-learning classes, and intercultural exchange at the heart of our SALC’s ethos, it is uniquely suited on our campus to the cultivation of a cross-departmental community and the development of intimate relationships both between faculty and students and among the students themselves. This differs significantly from, say, the university library, as that facility enforces silence throughout most of its public spaces and requires advance registration for most of its active learning spaces. While such rules may be amenable to silent reading and writing activities, they do not afford the dialogic processes foundational to community development that lay near the foundations of the English Lounge ethos. On the other hand, individual department facilities potentially do better at fostering community among their specific members, but they are exclusionary by their very nature. Furthermore, as international students primarily enroll in classes in the Department of International Education & Collaboration, they may find it difficult to interact with the general Japanese student population. Working as an English Lounge “supporter” or participating in events in the SALC provides a natural context for them to meet with Japanese students, and vice versa. Furthermore, beginning in 2023, the English Lounge has begun partnering with the Office for Promotion of Gender Equality, offering one of its rooms for a monthly “Sankaku Lounge” (an LGBTQ safe space), articulating the SALC’s commitment to providing a safe environment for all students on campus. This makes the English Lounge a unique and valuable intercultural community place on campus.

Bakhtin’s literary concept of dialogism offers potential for exploring SALC communities from a new perspective, as the concept has been fruitfully applied within the field of sociology, such as in Good’s (2001) study of clinical psychiatric hospitals. Dialogism assumes the responsibility of multiple subjects, or “human consciousnesses,” in polyphonically realizing new possible relations in a shared context, and may be conceived of as a critical element of collaborative learning and constructivism. Dialogue is posited in opposition to the monologic, which lacks any kind of interlocution—witness the traditional academic lecture, the sermon, government propaganda, or the corporate training video. Interlocutions in the SALC necessarily involve the collision of multiple chronotopes (Bakhtin, 1981); or, in Good’s words, “Community becomes an interdependent collection of differing timespaces [sic]” (p. 4). The student receptionist, faculty member, exchange-student supporter, single-time user, and regular user each occupies a differing chronotope, a different relation to the time-space of the SALC. Good applies this analytical instrument to the world of clinical psychiatry, in which doctors occupy a cyclical chronotope of (effectively) no-end, whereas the patients enter the space with an eye set on the horizon of discharge back into society—and thereby occupy a hopefully short-term teleological time-space. The parallels with campus life are stark: Students not only experience the four or so years of university education as a transitory phase; each new year is accompanied by an increase in educational demands and complexity, sophistication, expected competence, as well as shifting goals and modes of engagement with the campus and class communities. They experience a phenomenologically teleological relation to the campus time-space. Educators, by contrast, are not only typically entrenched in the academy for the span of their careers, but those affiliated with the English Lounge spend the vast majority of that time primarily in contact with freshmen students taking liberal arts English classes. Of course, one would be remiss not to acknowledge the unique chronotopic conditions of the precariat—of contingent academic laborers such as adjunct professors and graduate-student TAs—as well (although they are not employed in the specific case of the English Lounge). Like the clinicians, most teachers, including those affiliated with SALCs, relate to their classrooms and students in a cyclical, annualized timeframe.

The SALC community is constructed through dialogue between subjects occupying different chronotopes. As the students move through and interact with the space and—more importantly—experience phatic intersubjective encounters, they engage in a form of tactics that are constitutive of the English Lounge as a social space (de Certeau, 1984, pp. 91–100). As will be shown, survey respondents characterized the SALC as a social space in a variety of ways.

Positive responses pertaining to social relations, a non-judgmental atmosphere or the otherwise safe environment, personal relationships with teachers, and interest in the seminars as unconventional learning environments each stand in direct contrast to common demotivators for English learners. In a review of research about Japanese ESL students, for example, some of the common demotivators identified were: teachers (including attitude, personality, teaching style, etc.), characteristics of classes (including focus on grammar or vocabulary, exams, memorization, etc.), experiences of failure (including test scores, memorization, etc.), and class environment (attitude of classmates, compulsory nature, inactive classes, etc.) (Sakai & Kikuchi, 2009). Minimizing such demotivators in the SALC directly supports the development of the community and hopefully lays the groundwork for an “integrated orientation” toward language learning. Ushioda and Dӧrnyei (2009) theorize this orientation as motivation derived from social identification with a community and authentic, “sincere and personal interest” (p. 2). They contrast this to identification, “an internal process of identification within a person’s self-concept, rather than identification with an external reference group,” arguing that the reduction of dissonance between the socially constructed identity and the internal identity results in motivation (pp. 3–4). The data from the surveys below will suggest that members of the SALC community utilize de Certeau’s tactics in the context of phatic interactions to progress toward an integrated orientation vis-à-vis the English language.

Survey Data

While the English Lounge has recently begun to conduct broad, comprehensive user surveys (Solomon, 2024), two additional small-scale targeted surveys were undertaken on this occasion to help elaborate a more detailed picture. Rather than casting a wide net, the first survey narrowly targeted heavy-recurrent users, including both current students and graduates, and interrogated their motivational histories related to language learning and cultural exchange, as well as their image of the English Lounge. The second survey was directed at non-Japanese student “supporters,” aiming to explicate their conception and personal use of the SALC as a community space. In both cases, the limited number of survey respondents restricts the generalizability of the data; however, the broad congruity of the responses in many cases still offers insight into this particular community.

Survey #1: Heavy-Recurrent Users

Background

When setting the parameters of the survey, I began by referring to the basic data taken when students signed into the facility. Approximately 15 to 20 percent of English Lounge users in the 2022 academic year visited the SALC six or more times in a given 15-week semester (Solomon, 2024, p. 64). For the current survey, I decided to narrow the scope even further. With the goal of collecting responses from students who had a stable presence in the English Lounge community, I defined heavy-recurrent users as those who, at some point in time, visited the facility three or more times per week. While the extremity of this parameter certainly dramatically reduced the number of potential responses, it will allow us to gain a better understanding of this subset of students who see and utilize the English Lounge as part of their identity, as outlined in the theoretical introduction above.

Participants

The survey was advertised through flyers in the English Lounge and directed e-mails to alumni who had previously agreed to participate in research activities. Of the 15 responses collected, 12 passed the screening question and provided usable data. The years the respondents matriculated into the university included 2018 (2), 2019 (2), 2020 (3), 2021 (3), and 2023 (2). With the exception of two students who matriculated at the ages of 20 and 22, all of the other respondents first came to Hirosaki University at age 18 or 19.

There was some imbalance in the respondents’ profiles. Eight of the respondents were from the humanities and social science department, with the others spread across education (2), science and engineering (1), and agriculture and life sciences (1). The bias toward humanities and social science students may be explained by the physical proximity of the SALC to their faculty building. Conversely, the lack of medical students is likely explained by the fact that they spend the majority of their time on a physically separate campus.

Another imbalance was present in the gender of respondents: nine were female and only three were male. Research suggests that female English learners tend to be more autonomous than males in Japan and elsewhere (e.g., Yazawa, 2020; You et al., 2016) and score significantly higher in “integrativeness,” the socially-driven motivation toward language learning (Mitsuko, 2022; Mori & Gobel, 2006; Tanaka, 2023) mentioned above.

Materials

The survey was conducted using Microsoft Forms and was made available in both English and Japanese, the latter of which was the students’ first language. The data used in this paper was collected regarding the following topics:

- English use rate (Including study and recreation; 5-point Likert scale from “never” to “daily”)

- Motivations (Motivation to study English, motivation to use English, and motivation for intercultural exchange; 5-point Likert scale from “extremely low or no motivation” to “strongly motivated,” plus “not applicable” = “0”)

- Image of the SALC (6-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” -3 to “strongly agree” +3)

- Use/Evaluation of SALC Resources (4-point Likert scale from “rarely/did not use” to “daily or near-daily” for SALC resources use and from “not helpful at all” to “extremely helpful”, plus “did not use” = “0” for SALC resources evaluation)

The questions regarding motivation were chosen to prompt a longitudinal self reflection rather than to establish a present-day snapshot. Thus, it asked respondents to recall their motivations at different points in their education (e.g., elementary school, middle school, high school, etc.). Additionally, the Likert-scale questions were followed by a variety of free-response questions to continue prompting reflection and provide supplementary qualitative data.

Results: Motivation

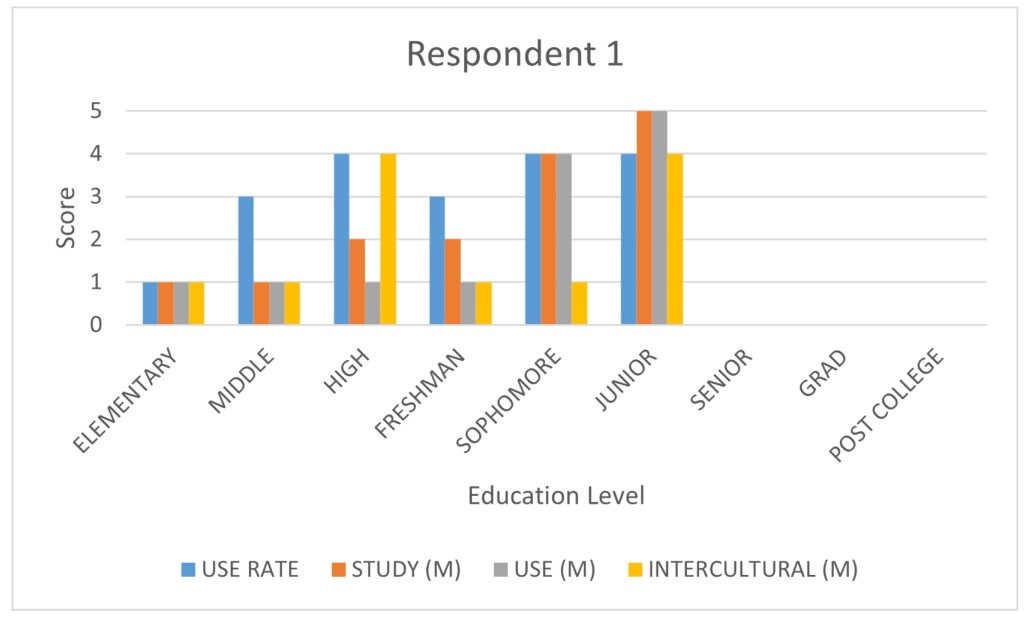

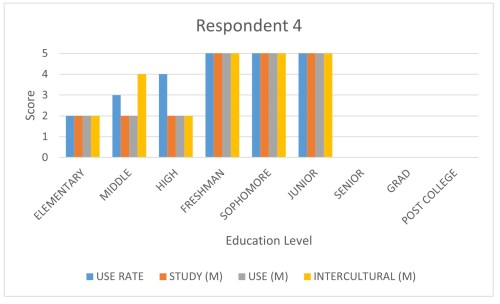

A large part of the survey focused on the English use and motivational histories of the students. In this section, I refer to three representative respondents’ data while analyzing some trends observed in the responses. The three representatives appear in Figures 1, 2, and 3, below. For clarity, items measuring motivation for language study, language use, and intercultural exchange are labeled with an (M):

Figure 1

Sample Comparisons of Actual Use of English and Motivational History, Respondent 1

Figure 2

Sample Comparisons of Actual Use of English and Motivational History, Respondent 3

Figure 3

Sample Comparisons of Actual Use of English and Motivational History, Respondent 4

Respondent 1 (Figure 1) somewhat anomalously discovered motivation for English only as a college sophomore. Respondent 3 (Figure 2) reports maximal motivation in all aspects beginning in middle school, a pattern similar to those of Respondents 2 and 6. Respondent 4 (Figure 3) saw a large increase in motivation in the transition between high school and college. This is the same as Respondent 5, and similar to Respondents 8, 10, 12, who also show an increase in motivation post-high school, but not as extreme. Finally, Respondents 7, 9, and 11 reported a steady, gradual increase in motivation and use of English throughout their educational careers, maxing out during their freshmen or sophomore years. The full data can be viewed in Appendix A. Note that the disjunction in many cases between the “actual use” of English and the motivational data likely derives from the role of compulsory English education in grammar school.

Still, motivation cannot simply be measured by a learner’s impressions and self-reportage. To supplement these personal narratives, the survey added additional open-ended questions regarding the circumstances of the respondents’ first visit to the SALC, as well as the conditions surrounding their choice to return. This contextual data provides additional perspective on the “self-access” aspect of the SALC. It is important to explain at this point that, due in part to the nebulous incorporation of the English Lounge into the liberal arts English curriculum, several teachers in the curriculum assign mandatory or otherwise incentivized usage of the English Lounge in a variety of capacities. This includes requiring students to visit the facility a certain number of times per semester, allowing students to use the English Lounge as one of several “self-study” assignment options, requiring students to conduct interviews or conversations with international student supporters employed by the SALC, assigning students to do Extensive Reading activities with books from either the library or English Lounge, etc. While the assigning of SALC use either as an option for bonus points or for mandatory assignments creates a situation of “guided learning” and may be dissonant with many educators’ ideal of an autonomous learning paradigm and true “self-access learning,” this is a simple reality of our university, as well as a number of other institutions in Japan (Solomon, 2019, p. 5).

All 12 respondents first visited the English Lounge in their freshmen year: eight during their first semester and four during their second. Seven respondents (2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, 11) reported beginning “regular use” of the SALC during the same semester as their initial visit, three reported regular use the following semester (Respondents 6, 8, 12), one two semesters later (Respondent 9), and one three semesters later (Respondent 1). The delay of a single semester between first visit and regular use does not correlate strongly with self-reported motivation; however, it is reflected in the data of respondents 1 and 9, both of whom experienced a significant delay between their first and continued visits.

Respondents were also asked to qualitatively report the circumstances surrounding both their first visit to the English Lounge and why they decided to return as a recurrent user. Five respondents clearly stated external motivations for first visiting the facility. These mostly included liberal arts English class assignments, but one respondent mentioned that they first visited because the English Lounge seminars (weekly active-learning classes with no registration, grades, or homework) are part of the International Department’s global leadership program (“Hayabusa College”) curriculum. In these cases, the students had little to no autonomy in their decision to visit the SALC. The remaining seven respondents, however, appear to have come out of intrinsic, instrumental, or otherwise some kind of internal motivation: a curiosity about an English Lounge seminar, a desire to overcome their lack of confidence in English, to prepare for study abroad, or to generally improve or use their English abilities. Of the five students who reported a delay between first visiting the SALC and beginning regular use, only two reported being strongly initially externally motivated (earning class credit), suggesting that in this case, the impetus for the initial visit was not a significant determining factor in their decision to return.

The reasons the respondents reported for returning to the facility regularly varied. The most common responses mentioned fun, enjoyment, or friends (Respondents 5, 6, 9, 10, 11). Some comments touched on classes—including using the SALC to supplement a lack of English classes in their faculty (Respondent 1) and using the SALC resources to help prepare assignments for another class (Respondent 2). Several respondents mentioned the role of the SALC teachers specifically (Respondents 5, 7, 12). Respondent 8 began using the English Lounge after returning from study abroad, Respondent 4 developed a habit of visiting through Extensive Reading, and Respondents 3 and 12 mentioned a general atmosphere of freedom and safety, which differed from that of regular classes. None of the respondents explicitly mentioned external motivators (mandatory class assignments) or specific instrumental motivators (language aptitude exam preparation, certification preparation, preparation for study abroad, preparation for work/job hunting, etc.) for bringing them back into the facility.

While not limited to motivations for returning to the English Lounge, respondents were also asked in a general way to “Please explain which external factors influenced your use of the EL the most. Was it the teachers, the classes, the other students, or something else, and why?” While the brevity of some of the responses introduces some ambiguity into their interpretation, only three of the 12 responses mentioned (non-SALC) “classes” (Respondents 2, 6, 7). Other answers included Japanese or foreign students (Respondents 1, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12) or the English Lounge faculty (Respondents 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12). None of the respondents mentioned the selection of books or DVDs; rather, they focused on more human factors.

By limiting Survey #1 to heavy-recurrent users of the English Lounge, I targeted students likely to be expressing an integrated orientation toward language learning, and their responses tended to demonstrate an attendant rise in motivation over time. This was also reflected in a high rate of response toward involvement in other intercultural and English-connected activities on campus, with an average of 4.75 activities per respondent. Motivation toward intercultural understanding and language learning in general was also demonstrated by self-reported overseas experience and a high rate of non-English foreign-language learning, with eight respondents listing between two to four additional languages (see Appendix B).

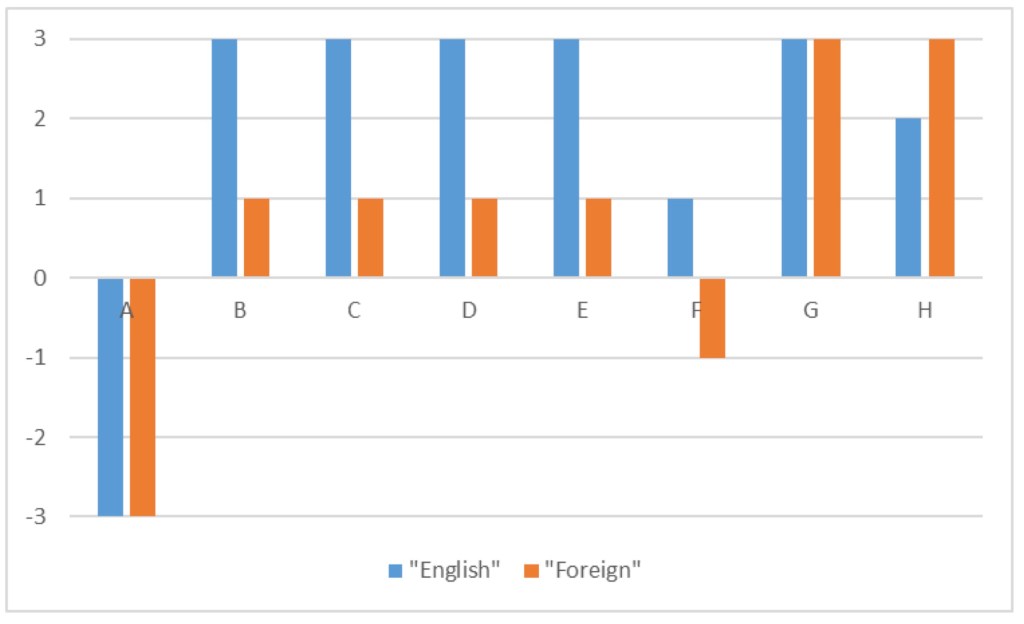

Results: Image of the SALC Versus Use of its Resources

The latter part of the survey focused on students’ image of the SALC and their use and evaluation of the resources available in the facility. The emphasis on sociality and enjoyment discussed above aligns with most of the respondents’ images of the English Lounge. For example, when asked to report the degree, they agreed with the statements “I see the EL primarily as a place for studying” and “I see the EL primarily as a place for socializing/having fun,” only one respondent slightly disagreed with the social image. Conversely, with regard to the image of the SALC as a study space, two respondents slightly disagreed, three disagreed, and two strongly disagreed. Only two respondents agreed more strongly that the SALC was a study space than a social space, as can be observed in the following graph (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Image of the English Lounge: Study Versus Social

There was less regularity in the answers when asked to what extent they agreed with the statements “When I think of the EL, I think of ‘English’ first” and “When I think of the EL, I think of ‘foreign culture’ first.” However, only two respondents disagreed with the image of foreign culture, indicating that the majority equated the English Lounge with not only English but also foreign culture, as apparent in the following figure:

Figure 5

Image of the English Lounge: English Versus Foreign Culture

The strength of the connection between the English Lounge and foreign image likely derives from the central role the conversation corner and international student supporters play. Indeed, regarding the use of SALC resources, the conversation corner proved the most well-utilized of all, with eight respondents reporting “daily or near-daily,” three reporting “weekly,” and only one reporting “monthly” use. The second most-used resource was the seminars. Three of the five faculty who teach them are not Japanese, and seminar lessons are often designed around foreign cultures, such as “German Culture” or “US History.” Five respondents attended seminars “daily or near-daily,” six attended “weekly,” and one attended “monthly.” Figure 6 illustrates the frequency with which each respondent used the various SALC resources.

Figure 6

Rate of SALC Resource Use

It appears that the rate at which the students engaged with different SALC resources correlated with the degree they found them to help their learning. Figure 7 shows the ratings for how helpful the respondents perceived the five main SALC resources.

Figure 7

Perception of SALC Resource Helpfulness

The seminars and conversation corner received high ratings overall, with only one weak rating given to seminars and two to the conversation corner.

Survey #2: International Student Supporters

Background

One of the core features of the English Lounge is the “English Lounge Supporters.” Supporters are mostly international students or exchange students who are employed to help Hirosaki University students practice English conversation, conduct cultural exchange, and provide feedback on their class assignments. With the exception of about two years when international travel was limited due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the SALC typically hires approximately 20 supporters per semester. In 2023, supporters staffed the conversation circle in three 90-minute shifts per day, with two supporters working simultaneously during crowded parts of the semester. Sometimes supporters are also asked to participate in seminars as TAs, usually to discuss their country’s culture. Supporters are compensated for their time from the SALC’s operational budget. They attend one orientation session per semester; however, unlike “tutors” in some other SALCs, supporters do not undergo specialized training and are not treated as teachers or educators. Indeed, while the primary language of the English Lounge is English, following the university’s liberal arts English policy, it emphasizes world Englishes and does not require more than conversational-level proficiency from the supporters. Rather than “teaching” in a top-down relationship, supporters are expected to act as peers to their fellow students and learn reciprocally from one another.

Participants

Survey #2 garnered only eight responses. Five of the respondents were female, three were male, and they were a mix of undergraduate and graduate students, ages ranging from 20 to 32. Six were registered to the faculty of education, and one each was in the humanities and science and engineering. Respondents’ ethnic backgrounds included Filipino, Chinese, German, Brazilian-Japanese, Japanese-Okinawan, Indonesian, and French-Canadian.

Materials

This survey was conducted using Microsoft Forms in English only. The entire survey consisted of 16 questions, including background information. The respondents were presented with the same Likert-scale questions regarding their image of the English Lounge as in Survey #1. They were also presented with open-ended questions regarding their use of Japanese and other languages in the facility, their reasons for applying for the position, what actions they took while on duty, their use of the SALC when not on duty, and what they gained from their experiences there.

Results

The small number of responses limits the generalizability of the data; however, the qualitative open-ended answers still provide some insight into the supporters’ role in the space. First, the image of the English Lounge for supporters both aligned and differed in some aspects from the heavy-recurrent users. Only two of the seven valid responses in Survey #2 disagreed with the English Lounge primarily being a place of study:

Figure 8

Image of the English Lounge: Study Versus Social

In addition, they had a much stronger impression of the SALC being English-focused, as opposed to foreign-culture-focused:

Figure 9

Image of the English Lounge: English Versus Foreign Culture

I hypothesize that, as these supporters likely spent a significant amount of time answering interview questions or giving feedback on homework assignments from low-frequency users that their perception of the English Lounge as a forum for “study” and “English” was naturally stronger than that of the heavy-recurrent users, who developed longer-lasting social relationships through habitual use of the space. Yet, the social element was still suggested by responses to a question about how and when the supporters used Japanese or other non-English languages. Half of the respondents (B, C, D, G) mentioned using their native language (Chinese, German, Indonesian) when other native speakers were present, suggesting that in those cases social interaction took precedence over English use. The other qualitative answers provided by the supporters illuminate this social perspective in more detail.

One item on the survey asked about the supporters’ motivations for applying for the job. Five of the eight respondents (A, C, D, F, G) mentioned a desire to socialize, make friends, or simply “meet” Japanese students. Five (A, B, F, G, H) also mentioned a desire for self-improvement, either to learn more about Japan, to “broaden [their] horizons,” or to improve their own English abilities. Only three (C, G, H) wrote about their potential to contribute to the education of the Japanese students, and only one (E) mentioned being motivated by the monetary remuneration.

The topic of social interaction arose again several times throughout the open-ended answers. Respondent F categorized their interlocutors as “newcomers and friends” when describing their actions on the job. Respondent A learned through their experience as a supporter how to coax the Japanese students into “sharing their life or knowledge with [me],” and also emphasized the need to learn to listen to others in dialogue rather than continue speaking themselves. Respondent B wrote about learning skills for “gaining friends,” and Respondent G also “gained some new friends.”

The topic of the atmosphere of the English Lounge also came up several times. Respondent C was sensitive to the fact that, for Japanese students, the SALC can potentially be “scary.” Respondent D tried to respond actively as students entered and left the space and “make them feel welcome.” Respondent B mentioned the importance of a “non-judgmental environment,” and Respondent H wrote about providing a “warm atmosphere that welcomes all.”

Finally, the supporters were asked to describe their use of the English Lounge while not on duty. Regarding how often they visited the SALC when off-duty, of the eight respondents, six (A, B, C, F, G, H) responded that they do or did use the space regularly. Three (A, B, H) described using the space for studying or reading. Three (C, G, H) also reported acting as a “semi-supporter” or otherwise helping students with homework or interviews to some extent when not on the job.

Discussion

The breadth of the two surveys was significantly limited, gathering data from a combined 20 respondents. However, an overview of the responses points to some emergent themes. The balance of the image of the English Lounge as a space for “English” versus “foreign culture” and “study” versus “socializing” were somewhat different in the two surveys: results of the Likert-scale questions show that the heavy-recurrent users see the English Lounge much more strongly as a place of “foreign culture,” and the international student supporters identify the space with “study” more than the Japanese students. At the same time, both populations strongly agree that the SALC is a place for “socializing” and “English.” Their qualitative answers additionally affirmed the SALC as a social space for culture exchange. The supporters’ qualitative answers, in particular, alluded to both an intention to use their role as an opportunity to develop social relationships, as well as a willingness to use Japanese and their native languages in addition to English in order to participate more effectively in their social community. Indeed, it is the qualitative answers from Survey #2 that most directly reflect de Certeau’s concept of tactics and phatic exchanges: here, through moment-by-moment choices of language, managing Japanese students’ stress levels, and decisions to variously utilize the SALC as a language learner themselves and to continue to support student learning even when off-duty.

In addition to the small number of respondents in the surveys, another limitation of this study relates to the interpretation of the self-reported survey data. While the above analysis describes the strongly social orientations of a subset of English Lounge users, it is important to remember that SALC use and motivation toward language learning do not necessarily translate into tangible (or testable) learning outcomes. As Respondent 10 remarked when asked to reflect after relaying their motivation history, “I am motivated, but I feel like I have not been able to translate that into actual study” (translated by author). According to a metanalysis by Okunuki and Kashimura (2024), motivational studies tend to focus on “behavioral engagement” (task-oriented persistence), “cognitive engagement” (attention and self-regulation), and “emotional engagement” (interest, enjoyment, and enthusiasm) (p. 72). They conclude that “engagement is [sic] a small, positive relationship with achievement in the order of cognitive, behavioral, and emotional” (p. 85). In other words, the type of engagement the respondents in the present study most clearly displayed—emotional engagement—correlates least strongly with testable language-learning achievement.

As described above, community may be conceptualized as a space for dialogic encounters, and indeed, socialization is an important aspect of language learning and has been connected to increased learner resilience (Kiyota, 2021). Furthermore, socialization in a multicultural context can contribute to long-term participation in a language-learning community (Schiller, 2021). The data collected in the surveys above aligns with these earlier findings. The heavy-recurrent users recognize the English Lounge as a social space, and they primarily utilize it for conversation, cultural exchange, and active-learning seminars. While they had a variety of reasons for visiting the facility the first time, many established a pattern of use as the result of human interactions with foreign student supporters, fellow Japanese students, and teachers. While the English Lounge supporters were paid for their service in the SALC, the majority reported utilizing the space during their free time, and many referred to socialization, “friends,” and self-improvement in their responses. This emphasis of the social function of the SALC is not unique to the English Lounge: SALCs in Japan tend to be used as social spaces—not only by Japanese students, but also exchange students and, in some cases, even faculty members (Solomon, 2019, p. 8).

As we approach the SALC as a polyphonic community, we can offer it to the notion of the chronotope, and thereby attend to our students from a fresh perspective. Thus, rather than assuming there is a “problem” requiring a solution with one-time or infrequent users of the facility, it may be productive to reconceptualize them as maintaining a different consciousness with respect to how and when they may occupy the space. One-time users often utilize the space due to class requirements, not relating to the place habitually or cyclically, but rather with a short-term goal frame of mind. A chronotopic approach would suggest that instead of focusing exclusively on causative-verb-based measures (“make them comfortable in the space,” “make them enjoy English,” “make them study harder”) we may try introducing messaging relating to the conception of habitualized SALC use (“The English Lounge is a place to build community,” “The English Lounge is a place to support daily study habits,” “The English Lounge is part of campus life”). I hypothesize that the change in temporal relation should coincide with an evolution toward an integrated orientation toward the language-learning community, similar to the results of the extensive reading exercises in Shibata (2016). The respondent who initially built a habit of reading in the SALC is exemplary of how developing a habitual use of the space can prepare the subject for an inter-subjective communal relationship as well.

If the primary goal of a SALC is to concretely improve student English ability or raise their test scores, fostering community through emphasizing the social aspect of the space may lead to limited outcomes. On the other hand, if the purpose of a SALC is to inculcate human subjects with an enjoyment and desire to engage in English communication or intercultural communication, then the data presented here may describe success stories. This would be doubly true if the participants in the survey had, through their time in the English Lounge, gained the tools (linguistic, social, strategic, etc.) necessary to continue that learning process autonomously. As this point and the issue of achievement were beyond the bounds of this current study, they should be returned to for further consideration in conversation with the community aspect of the SALC. However, I stress that the non-Japanese participants in Survey #2 should not be discounted either. While, institutionally, they may be viewed as merely incidental members of the SALC in comparison to the assumed-Japanese full-time university undergraduate students, their answers reflect the affective and social qualities of their labor as well as the potential function of the SALC as a communal space. Through daily observation and interactions, I have come to recognize the value of its community for all classes of participants in that space—a topic worthy of continued analysis and reflection.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to all the students who responded to the surveys and contribute to the English Lounge community.

Notes on the Contributor

Joshua Lee Solomon is a lecturer in the Hirosaki University Institute for the Promotion of Higher Education. He teaches in the university SALC and liberal arts English program. His EFL research interests include intralingual translation, literature in language teaching, materials production, and culturally-familiar materials. In addition, he conducts research on Japanese-language literature on the themes of place, minority, and colonialism in northeastern China.

References

Bakhtin, M. (1981). Forms of time and chronotope in the novel. In M. Holquist (Ed.), The dialogic imagination: Four essays (84–258) (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, trans.). University of Texas Press.

de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life (Rendall, S. trans.). University of California Press.

Good, P. (2001). Language for those who have nothing: Mikhail Bakhtin and the landscape of psychiatry. Kluwer Academic.

Hooper, D. (2020). Modes of identification within a language learner-led community of practice. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 11(4), 301–327. https://doi.org/10.37237/110402

Kiyota, A. (2021). Group dynamics and resilience in the process of L2 socialization: A longitudinal case study of Japanese university students visiting an English lounge. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 12(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.37237/120103

Mitsuko T. (2023) Motivation, self-construal, and gender in project-based learning. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 17(2), 306–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2022.2043870

Mori, S., & Gobel, P. (2006). Motivation and gender in the Japanese EFL classroom. System 34(2), 194–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2005.11.002

Mynard, J. (2020). Exploring identity in a social learning space. Mynard, J., Burke, M., Hooper, D., Kushida, B., Lyon, P., Sampson, R., & Taw, P. (Eds.), Dynamics of a social language learning community: Beliefs, membership and identity (pp. 93–107). Multilingual Matters.

Okunuki, A., & Kashimura, Y. (2024). Student engagement and academic achievement in second language learning: A meta-analysis. JACET Journal, 68, 71–90.

Sakai, H., & Kikuchi, K. (2009). An analysis of demotivators in the EFL classroom. System, 37(1), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2008.09.005

Schiller, A. (2021). Building language skills and social networks in an advanced conversation club: English practice in Lecce. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 12(1), 70–78. https://doi.org/10.37237/120105

Shibata, S. (2016). Extensive reading as the first step to using the SALC: The acclimation period for developing a community of language learners. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(3), 312-321. https://doi.org/10.37237/070307

Solomon, J. L. (2019). Autonomous learning versus guided learning in Japanese SALCS: A preliminary survey. Journal of Liberal Arts Development and Practices, 3, 1–9.

Solomon, J. L. (2024). English Lounge self-access learning center comprehensive user survey: Results and subsequent facility improvements. Journal of Liberal Arts Development and Practices, 8, 63–73.

Tanaka, M. (2023). Motivation, self-construal, and gender in project-based learning. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 17(2), 306-320. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2022.2043870

Tatsuta, N. (2023). Hirosaki Daigaku ni aru kyōzai/fukukyōzai [Teaching materials and supplementary materials at Hirosaki University]. In Y. Yokouchi (Ed.), Hirosaki Daigaku kyōyō kyōiku eigo kamoku gakushū gaido bukku [Hirosaki University liberal arts English curriculum study guidebook]. Kinseido.

Ushioda, E., & Dӧrnyei, Z. (2009). Motivation, language identities and the L2 self: A theoretical overview. In Dӧrnyei, Z. & Ushioda, E. (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 1–8). Multilingual Matters.

Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (June 2015). Introduction to communities of practice: A brief overview of the concept and its uses. Wenger-Trayner: Global theorists and consultants. https://www.wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/

Yazawa, O. (2020). Gender differences in self-determined English learning motivation in a Japanese high school. Journal and Proceedings of the Gender Awareness in Language Education Special Interest Group, 12, 28–44.

You, C., Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (2016). Motivation, vision, and gender: A survey of learners of English in China. Language Learning, 66, 94–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12140

Appendix A

Survey #1 Motivational Histories (see PDF version)

Appendix B

Survey #1 Additional Data (see PDF version)

Non-SALC English and Cultural-Exchange Related Activity Participation

Overseas experience and additional languages studied