Reik Jagno, Institute for the Promotion of Higher Education, Hirosaki University, Japan

Jagno, R. (2024). Integrating Hirosaki University’s SALC into a Minor Program. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(4), 453–465. https://doi.org/10.37237/150406

Abstract

This summary article explores the development and implementation of minor programmes at Hirosaki University, with a particular focus on the Advanced Language Learning Minor and its integration with the Self-Access Learning Centre (SALC). Drawing from historical and contemporary perspectives on liberal arts education, the paper examines how the concept of minor programmes at Hirosaki University aligns with and diverges from traditional Western and Japanese educational practices. One minor offered at the university, the Advanced Language Learning Minor, specifically leverages the SALC to provide structured guidance for students seeking to enhance their language learning skills and autonomy. By integrating SALC resources into a formal minor programme, Hirosaki University supports independent learning while providing students with official recognition for their achievements. The paper concludes with recommendations for further development and expansion of the minor programme, considering the positive outcomes and demand observed.

Keywords: minor programme, SALC, autonomous learning

Higher education is a process that has developed over the centuries, yet certain foundational elements remain present in today’s education systems. One of the most influential models globally is the Humboldtian model of higher education. According to this model, certain kinds of knowledge should be of a general nature, and more importantly, there should be a cultivation of the mind and character as the basis of all education (van Bommel, 2015). The model advocates for individuals to be well-rounded and well-informed human beings. Vocational skills can be acquired later if this foundational education is established. This philosophy underlies why many countries, including Japan, adhere to the ideal of liberal arts education (from the Latin liberalis, meaning “free”, and ars, meaning “principled practice”). In this context, the term “art” refers to a learned skill rather than specifically to the fine arts. Liberal arts education is designed to provide a basic foundation and nurture a broad set of interests. Although the term “liberal arts” for an educational curriculum dates back to classical antiquity in the West, its meaning has evolved considerably, expanding over time.

Historically, the seven liberal arts subjects were divided into the trivium (rhetoric, grammar, and logic) and the quadrivium (astronomy, arithmetic, geometry, and music). In its modern sense, the term usually encompasses all the natural sciences, formal sciences, social sciences, arts, and humanities. While every university tends to have its own, slightly different interpretation and implementation of Liberal Arts, Hirosaki University decided to focus on the points of “foresight” and “ability to solve problems” (Hirosaki University, n.d.). Foresight is described as the goal to think from multiple angles and to reflect on multiple values via learning outside of your own field of research. This should cultivate the ability to see multiple directions and have more approaches to a topic. Specifically, Hirosaki University focuses on “glocal” issues, local and global issues facing international and local communities. The “ability to solve problems” part of the Liberal Arts program is therefore based on the concept of taking on the challenge of solving these issues as individuals and in teams.

Nowadays, university students can choose from, or are required to follow, a wide variety of topics. These choices can be overwhelming, and students might feel uncertain about which path to follow.

To address this, Hirosaki University implemented “Minor Courses” two years ago. This paper will explore the concept as used at Hirosaki University, which follows the American concept of minor courses in name only. It will specifically examine a particular minor course called “Advanced Language Learning” and its connection to the Self-Access Learning Centre (SALC) at Hirosaki University.

Understanding Minor Programs at Hirosaki University

The Concept of Minors

In the United States, a college minor is a secondary concentration of courses that students can choose to pursue alongside their major. While a major typically requires a substantial commitment of credit hours, a minor generally involves about 18 credits. (Claybourn, 2023) This allows students to gain additional credentials with a relatively smaller investment of time and effort. Minors are an excellent way for students to broaden their academic horizons, explore new interests, or enhance their qualifications in complementary fields by providing specialised knowledge in a related discipline. They are a great way to develop skills in an area related to the major or even outside of the primary field of study.

Minors allow students to explore their interests and offer an easy way to complete the necessary credits in addition to major courses. Ideally, students can take one course each semester, ensuring they have more than enough time to fulfil the course requirements. Minors are also excellent for introducing students to other areas of study they might not have otherwise considered. A significant factor is the opportunity to present their specialities in a more meaningful way to potential employers.

Unlike in the United States, where minors have been a longstanding component of the higher education system, the concept of a minor is only slowly gaining traction in Japan as universities begin to recognise the value of offering students flexible learning paths. This shift reflects a trend in Japanese education towards fostering creativity and adaptability in students.

Hirosaki University began developing minors around four years ago, with the specific goal of allowing students to take a more focused approach to the wide range of liberal arts subjects available. Students have the opportunity to obtain a certificate upon completing a minor, but it is not mandatory to choose one. In this context, the minor is more akin to European/ German Schlüsselkompetenzen (key competence courses) or Zertifizierungsprogramme (certification programmes).

A “key competence” course is designed to equip students with essential skills and abilities valuable across various fields and professions. These courses often focus on developing transferable skills that complement academic knowledge and enhance employability. Common courses include interdisciplinary skills, which aim to provide skills not specific to a single discipline but applicable in a wide range of professional contexts. Courses cover common topics such as communication skills, teamwork, problem-solving, leadership, and time management. Language skills, which encompass various language courses, are often part of key competence offerings. More recent offerings include topics like digital competencies, focusing on skills such as data analysis, digital communication, and information technology, as well as Personal Development courses, which cover self-management, stress management, and intercultural competence.

At Hirosaki University, most minors are an extension of the faculty classes and allow students to dive deeper into their field of study. As a unique development of the minor program, the university decided not only to design courses within the faculties but also to attach four minor programmes directly to the Centre for Liberal Arts Development and Practices. Instructors who work in the centre manage these minor programmes and teach classes for them. This approach is distinctive, as these courses are designed to offer a broader perspective on liberal arts, focusing on students’ soft skills and language needs. In contrast, the minors offered by the faculties complement the diverse major programmes available at the university.

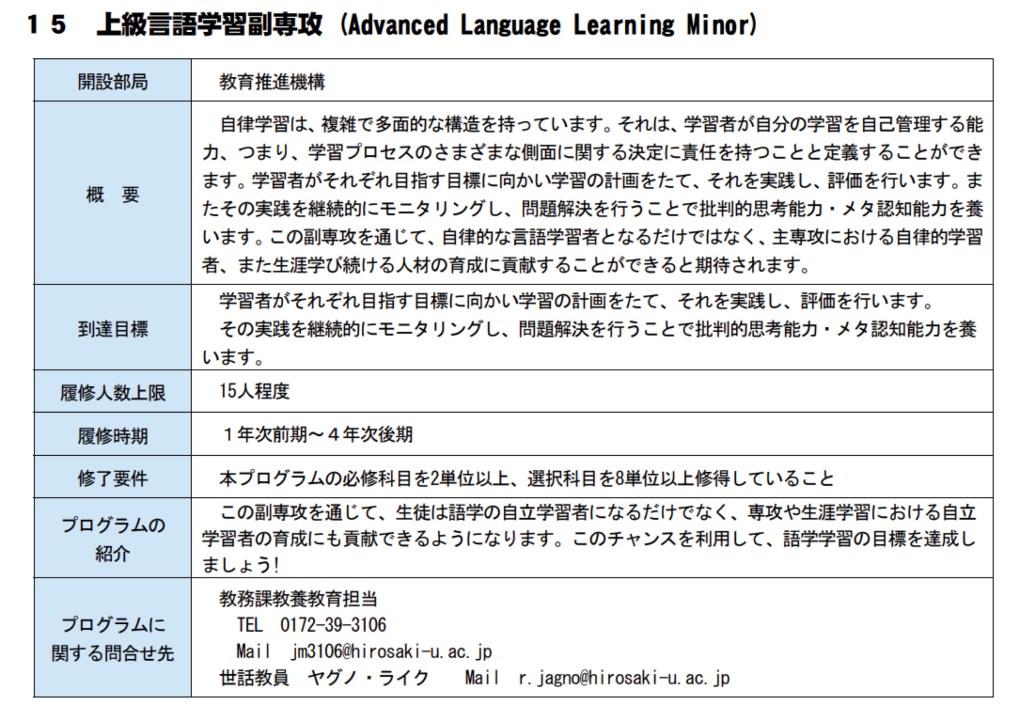

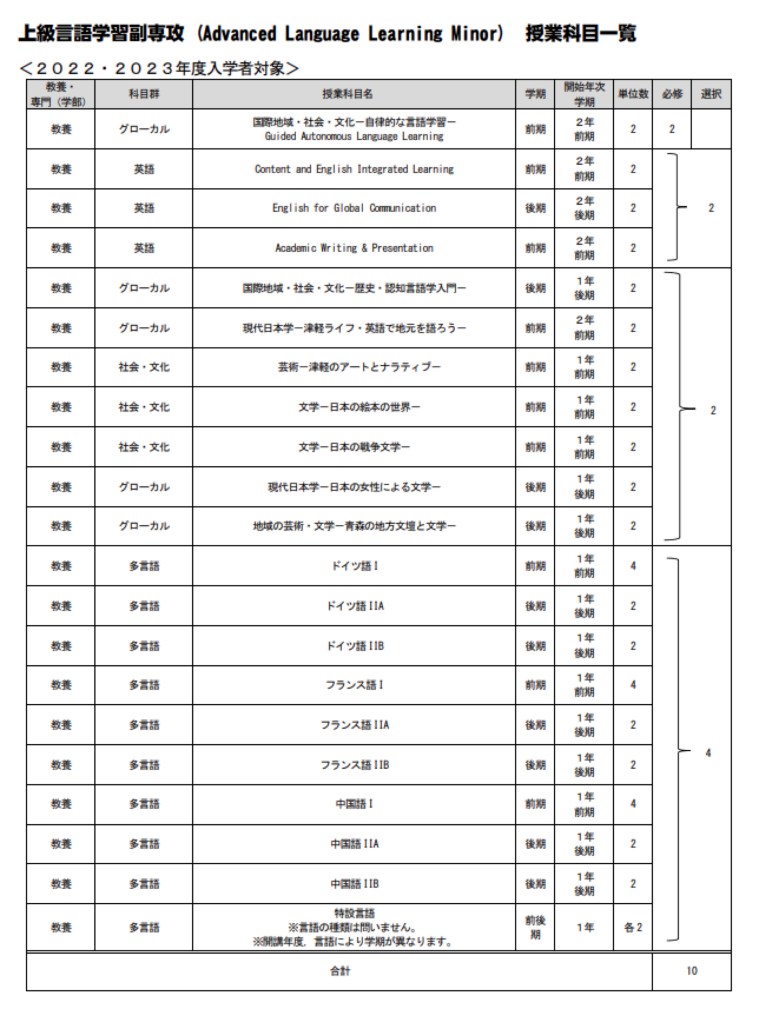

The four minors cover a range of topics. The Gender and Equality minor is akin to gender studies courses provided at various universities. The International Liberal Arts minor encourages students to study in English or other languages, strengthening Hirosaki University’s identity as a “glocal” institution and connecting local and global topics. Another minor focuses on language skills, while the final one, the “Advanced Language Learning” minor, not only covers language skills but also emphasises the importance of autonomous learning, self-improvement, and effective study techniques (see Figure 1 for the university description of the minor in Japanese, which describes the content and goals of it). Figure 2 shows the required and elective courses for completing the Advanced Language Learning minor programme. For example, as part of this minor, all students are required to take the “Guided Autonomous Language Learning” course and then select from a variety of Advanced English, Liberal Arts, and other non-English foreign language courses besides English.

Figure 1

Description of the Advanced Language Learning Minor

Figure 2

Required and Elective Courses to Fulfill the Advanced Language Learning Minor

The Advanced Language Learning Minor

Introduction to Advanced Language Learning

The term “learner autonomy” was originally coined by Henri Holec (1981) with adult education in mind. Since then, many definitions of learner autonomy have emerged, varying by author, context, and the level of debate among educators. Learner autonomy represents a consistent form of learner orientation, with the fundamental idea that learners should be empowered to determine their own goals, content, methods, working techniques, forms of evaluation, and temporal and spatial learning environments. Learner autonomy and self-directed learning correspond to constructivist learning theory.

In Japan, learner autonomy has given rise to the opening of Self-Access Learning Centres across the country, with many basing their core principles on this autonomy (Mynard, 2019). Autonomy means independence and the right to self-govern. In education, it is related to the notions of negotiation, participation in classroom decision-making, reflection and choice, independence, self-evaluation, and cooperation, among others.

Autonomous learning is a complex and multifaceted construct. According to Holec’s definition, it can be seen as learners’ capacity to self-direct their learning, which involves taking responsibility for decisions concerning various aspects of the learning process. In self-directed learning, learners’ choices primarily relate to learning management, such as selecting materials, methods, the place and time of learning, and partners (Holec, 1981).

However, autonomous learning encompasses more than just its management aspect. Autonomous learning involves on the cognitive side critical thinking, planning, evaluating learning, and reflection. It requires a conscious effort by the learner to continuously monitor the learning process from beginning to end (Benson, 2001). An autonomous learner is, therefore, a reflective learner, actively engaged in reflective learning. Autonomous learners take responsibility for their learning not only at the management level but also cognitively. They are willing to make a conscious effort to understand what, why, and how they are learning (Little, n.d.).

Finally, autonomous learners are less dependent on their teachers. However, even though the idea is often wrongfully repeated, there is no autonomous learning without teachers (Benson, 2001). Their primary role in the classroom is not the transmission of knowledge but rather to act as organisers, advisers, and sources of information.

As previously mentioned, learner autonomy is one of the cornerstones of SALCs. However, Hirosaki University only had a limited way of providing guidance for students on their way to becoming autonomous learners in its SALC (called the English Lounge). Like many universities, time and financial constraints, as well as workforce considerations, limit the possibilities for the SALC. This doesn’t imply that there was no guidance provided at Hirosaki University’s SALC in the past, but guidance was often offered in an unstructured way and heavily reliant on the willingness of faculty members to spend their time in the SALC, meaning they couldn’t do other job-related tasks. By embedding the SALC within the minor, students have structured access to advice and materials that support their language learning, thereby enhancing their experience and engagement inside and outside the traditional classroom. Receiving a certification of finishing the minor not only serves as formal recognition of their skills and efforts but also provides a tangible asset for job hunting.

Objectives and Learning Outcomes

The primary objective of the Advanced Language Learning Minor is to equip students with the tools necessary to learn languages independently. The language learned is of a secondary nature, and students have chosen other languages besides English for their studies in the past (see Figure 2 for the language options available for this minor). Upon completion of the program, students are expected to have achieved a high level of proficiency in their chosen language, as well as a deep understanding of effective language learning strategies. The program also aims to foster critical thinking, problem-solving, and cultural awareness—skills that are invaluable in today’s globalised society.

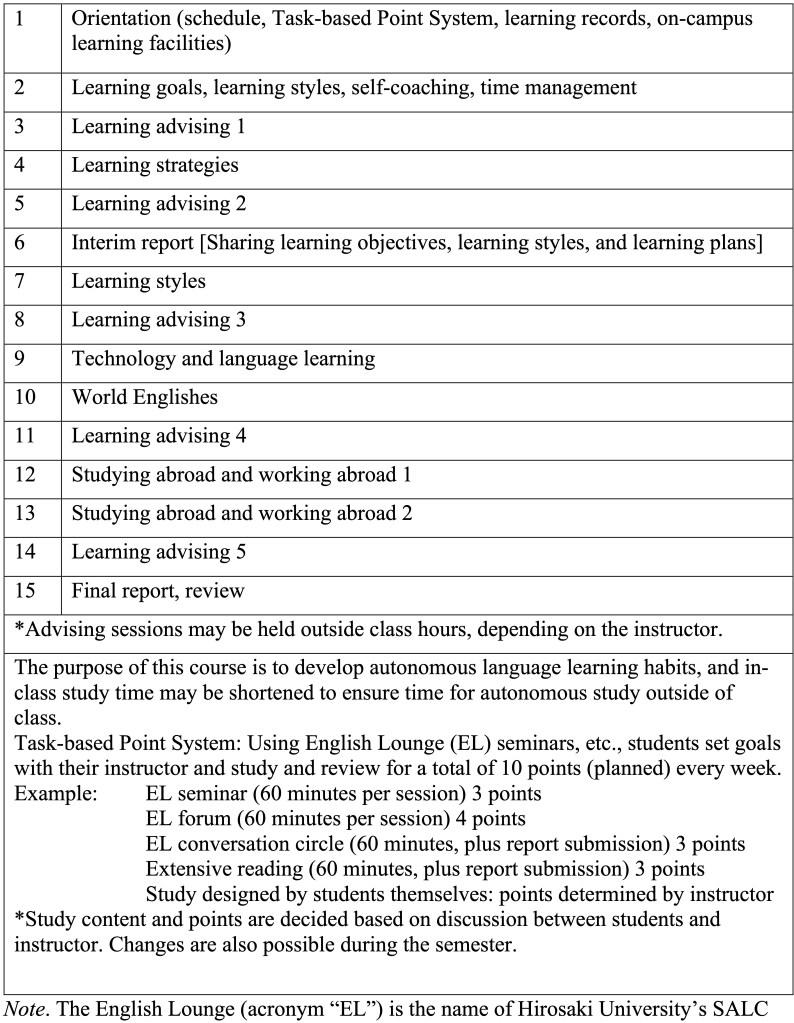

The one required course that all students need to take to complete this minor is called Guided Autonomous Language Learning, which is divided into three main sections (see Figure 3 for the syllabus). Firstly, learners are expected to acquire techniques from faculty members to enhance their learning strategies, improve their self-awareness as learners, and better understand their individual needs. In the second section, students are required to study the language autonomously each week, following a previously agreed point system. This system ensures that sufficient activities are undertaken and that these activities align with the students’ personal learning objectives. For this purpose, students select one of three advisors and are encouraged to choose the one most closely aligned with their learning interests. Finally, students must report their successes and challenges to the class, fostering mutual encouragement and supporting the journey towards becoming independent learners.

Figure 3

Syllabus for the Guided Autonomous Language Learning Class

Currently, three instructors jointly teach this course, each bringing a unique perspective. The instructors represent a diverse range of expertise. The first is a native English speaker from the United States who has a strong command of Japanese, enabling him to offer students insights from a native speaker’s perspective while drawing upon his extensive experience learning Japanese. The second instructor is Japanese and possesses advanced English skills. She can effectively leverage her own experiences and is well-positioned to understand and categorise the challenges faced by Japanese students. The third member of the team is German, having learned English at a young age. His role involves providing guidance on exchange programmes and the practical application of language skills, drawing from his own experiences as a language learner. These complementary roles collectively address the diverse needs of the students.

Students have the opportunity to select one of the three instructors as their primary mentor. They are required to report to their mentor regularly and develop their weekly plan in collaboration with them. This weekly plan operates on a points system, in which students negotiate with their mentor each week based on their learning objectives. The class is structured into a practical segment and a consultation segment. This arrangement ensures that students have both the opportunity and the obligation to engage with their mentor during class, thereby minimising the risk of a learner dropping out without making progress. Consultations are conducted either in group sessions or individual meetings, depending on the mentor’s approach. Both methods have proven effective: group sessions facilitate a greater exchange of ideas and inspiration, while individual sessions provide a more focused analysis of each student’s progress.

In addition to individual support, a structured programme is also in place. The tasks within this programme are divided among the instructors. The Japanese instructor explains the core concepts, while the foreign instructors share their personal experiences and describe their strategies. The distinct approaches to language learning presented by each instructor offer a variety of perspectives, allowing students to reflect on their own journeys as lifelong language learners and allow them to gain inspiration from various methodologies.

However, this comprehensive support system places significant demands on the teaching staff. Unlike courses with multiple instructors, all three instructors are present in every class and must also maintain contact with students outside the classroom. Given that traditional mentoring would not be feasible outside the context of such a course, the participating instructors have made a conscious decision to commit to this additional effort.

How Autonomous Language Learning is Facilitated

Hirosaki University offers a variety of resources to support students in their autonomous language learning journey, and this class is an opportunity to present these resources and the ones outside of the university to the students. We encourage the students to share newly discovered resources with their peers. Students are motivated to explore different learning methods, which include access to the SALC, the library, online platforms, and an abundance of language learning materials. Technology plays a role in the programme, with digital tools and applications providing students the opportunity to pursue their interests and discover technologies that may be of use. At the same time, the goal of the class is learner autonomy, so we provide the students the chances to find material on their own and to present it to the audience. Actual examples from the Guided Autonomous Language Learning class include chatbots, blogs, and student-developed software designed to extract word lists from books. Participation in the SALC seminars is also highly encouraged, offering students the opportunity to engage with a wide range of topics and improve various skills.

Why do we need a class for a class for guided autonomus language learning, and why should students not pursue these activities independently outside the classroom? The class setting offers a system of checks and balances that helps students remain motivated. Additionally, students are more likely to exchange ideas and communicate openly in this environment, often more so than in their typical individual study habits. Ideally, students will be able to find their own learning community and continue in it on their way as lifelong learners. However, the most significant benefit is that students are prompted to reflect on the opportunities and reasons behind their participation in specific activities. While all SALC seminars serve a valuable purpose, the class structure encourages students to consider the skills they are developing through these sessions. Typically, students participate in topics of interest without clearly identifying which skills they are improving each seminar. Mentoring and in-depth discussions can help address this gap, ensuring students gain a clearer understanding of the competencies they are acquiring.

Experiences of Students and Faculty

The success of the Advanced Language Learning minor is evident through the experiences of both students and faculty. In their final reflections, students reported that the programme improved their language skills, broadened their perspective on learning, and boosted their confidence in using the language in real-world contexts. Faculty members emphasise the programme’s focus on self-directed learning as a key contributor to its success. By enabling students to tailor their learning experience to align with their personal goals and interests, the programme fosters high levels of engagement and motivation.

It is also essential to highlight the shift in the teacher’s role within this framework. Rather than engaging in traditional, didactic instruction, the teacher acts as a facilitator, offering guidance, supporting students’ ideas, and encouraging exploration. Teachers must allow students to try things on their own, even if it doesn’t lead to the intended results and, more importantly, assist them in learning from those trials. Their role is to support students in the aftermath of challenges, helping them rebuild confidence, and offering ideas and solutions without stifling the delicate process of students’ autonomous development.

The SALC plays a crucial role in the students’ activities. As a repository of various curated resources for students to utilise in their learning journey, many of the students’ weekly points are earned through assignments that involve visiting the SALC. This approach has several implications. Firstly, it enables students to better understand how to effectively utilise the diverse resources available at the SALC. One of the challenges at Hirosaki University is that the daily activities in the main room of the SALC is supervised only by student assistants. Although the space is accessible to all university students, without guidance from faculty or staff, they are required to discover effective learning methods independently. By integrating this knowledge into the classroom, participants have the opportunity to apply it within the SALC and share it with other users.

Moreover, course participants influence the SALC’s seminars. While these seminars are voluntary and attendance cannot be accurately predicted without a registration system, the involvement of course participants who choose to attend provides greater planning reliability. It ensures that a core group of motivated and familiar participants will be present, which increases the stability of participating students in these seminars and, in turn, likely enhances the instructors’ preparation for them. This consistent participation also contributes to the overall quality of the seminars, as the students are naturally more engaged and accustomed to the course structure, and thus, they can motivate other participants.

The programme is currently undergoing continuous development. Initially, it attracted students seeking better language skills, but recently students participate to enhance their effectiveness as learners in a university setting, with a focus extending beyond English language acquisition. Furthermore, a growing number of international students have enrolled to improve their Japanese language skills. This latter development is particularly noteworthy, as international students often face unique challenges and can easily feel overwhelmed in a foreign academic environment. Participation in this programme serves to bridge the gap between the minor, exchange programmes, and broader liberal arts courses, offering the potential for advancing the university’s internationalisation efforts. In the immediate future, we plan to increase the frequency of the programme’s offerings, given the clear demand from students, as evidenced by the solid participation numbers and positive feedback regarding their experiences.

Nevertheless, the success of the programme heavily relies on the additional efforts of the participating instructors. This commitment not only limits their ability to complete other responsibilities but also proves mentally demanding, as mentoring young adults often involves navigating emotional highs and lows, requiring instructors to be prepared to support their mentees through these challenges. Moreover, while the principle of learner autonomy is highly valuable, it takes time for students in Japan, perhaps more so than in other countries, to adapt to the course’s role and its unconventional structure.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the integration of minor programmes, such as the Advanced Language Learning Minor at Hirosaki University, presents a strategic opportunity for universities to enhance their Self-Access Learning Centres and liberal arts education. By providing structured learning paths that incorporate SALC credits, universities can attract motivated students, whose engagement in such programmes positively impacts the broader student body. This leads to a more dynamic learning environment within the SALC, encouraging greater participation from students outside of the minor as well. Additionally, the minor programme offers valuable mentoring opportunities for faculty members, enabling them to provide focused, in-depth guidance to students, a task that would otherwise be difficult to justify in terms of time allocation. This approach not only strengthens the opportunities for students in the university but also supports the university’s overarching goal of fostering independent, self-directed learners who are well-prepared for the demands of a global society.

Notes on the Contributor

Reik Jagno is an assistant professor in the Hirosaki University Institute for the Promotion of Higher Education. He teaches in the university SALC and liberal arts classes. Next to the day-to-day operation of the SALC, he is especially involved in the hyflex outreach programs of the SALC. His research interests include teacher and learner autonomy, English as Global Language and the history of education in Japan.

References

Benson, P. (2001). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. Longman.

Claybourn, C. (2023, September 11). What a minor is and why it may (or may not) matter. U.S. News & World Report. https://www.usnews.com/education/best-colleges/what-is-a-college-minor

Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy in foreign language learning. Pergamon.

Hirosaki University (n.d.). 教育課程編成・実施の方針及び卒業認定・学位授与の方針 [Policy on curriculum organisation, implementation, and degree conferral]. https://liberal-arts.hirosaki-u.ac.jp/curriculum/

Little, D. (n.d.). Language learner autonomy: What, why and how? Post Primary Languages in Ireland. https://www.ppli.ie/images/Language_Learner_Autonomy_WhatWhyHow.pdf.

Mynard, J. (2019). Self-access learning and advising: Promoting language learner autonomy beyond the classroom. In H. Reinders, S. Ryan, & S. Nakamura (Eds.), Innovation in language teaching and learning (pp. 185–209). Springer.

van Bommel, B. (2015). Between “Bildung” and “Wissenschaft”: The 19th-century German ideal of scientific education. EGO – European history online. Institute of European History. https://d-nb.info/1125541547/34