Brian J Birdsell, Institute for the Promotion of Higher Education, Hirosaki University, Japan

Saki Niioka, School of Clinical Psychological Science, Hirosaki University, Japan

Birdsell, B. J., & Niioka, S. (2024). Integrating a SALC into a short-term study abroad program: Analyzing one former student’s experience. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(4), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.37237/150402

Abstract

Over the past 20 years, many universities in Japan have established self-access learning centers (SALCs) on their campuses. Proponents highlight the benefits SALCs offer to learners such as spaces for conversation practice, fostering friendships, supporting both guided and autonomous learning, and facilitating cross-cultural interactions. However, SALCs often remain isolated within their institutions, prompting growing interest in how to better integrate them into the broader university environment. In this paper, we first describe how the SALC at Hirosaki University has been integrated into Hayabusa College (a short-term study abroad program). Then, using an autobiographical narrative based on the second author’s experiences as a former Hayabusa student and English learner, we analyze key stages of her learning process. Framed within the context of Self-Determination Theory, we examine how her basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, relatedness, and a fourth candidate need, novelty—were met. The paper highlights the potential of autobiographical narratives to trace language learning progress and demonstrate the role of SALCs in this process, offering insights into the unique experiences of language learners.

Keywords: self-access learning, basic psychological needs, study-abroad, autobiographical narrative

The etymology of the word “educate” comes from Latin and means to nurture. Thus, education is about nurturing learners, both physically and mentally. This might include encouraging them to explore new ideas and unfamiliar territories. The goal is that through these experiences, one can grow and develop as an individual and reach one’s potential in life. One way to do this is by providing students opportunities to step outside of their everyday routines, familiar environments, and comfortable behaviors. This can be achieved through traveling overseas. Studying abroad offers numerous benefits, including the development of intercultural competence (Williams, 2005), increased world-mindedness (Cushner & Mahon, 2002), and the opportunity to build self-confidence and adaptability skills (Gmelch, 1997). Additionally, research has shown that studying abroad enhances problem-solving skills (Pearce & Foster, 2007) and fosters creativity (Maddux & Galinsky, 2009). It also positively impacts students’ motivation to learn a new language (Fryer & Roger, 2018). Therefore, studying abroad offers cognitive, motivational, and attitudinal benefits for the student.

This article is organized into three sections. In the first section, we describe a special short-term study abroad program designed by Hirosaki University called Hayabusa College. In the second section, we examine how Hirosaki University’s self-access learning center (SALC) is integrated into this program to optimize opportunities for the students to prepare for their studying abroad experience, and how the SALC provides a space for them to grow and improve their well-being within an English as a foreign language (EFL) context. Finally, the second author, a former Hayabusa College student, uses an autobiographical narrative to reflect on her experiences in this program, the challenges she had to overcome, and how the experiences in this program and at the SALC affected her motivation and emotional connection with English. Using these reflections, the satisfaction and frustration of her basic psychological needs in an EFL context, is considered in relation to Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017)

Hayabusa College

Hirosaki University’s Hayabusa College is a program developed by the former Center for International Education (currently named Department of International Education and Collaboration). In 2024, the program is now onto its 11th cohort and each group usually has around six to eight students participating in this program. To gain acceptance into Hayabusa College, students must first complete an application, participate in an entry period lasting one semester, and attend an interview. Final selection is based on their interview performance, participation in SALC activities during the entry period, and their score on a standardized English exam (TOEIC or TOEFL).

The program has undergone several design changes over the past decade. In the current design, it lasts for two semesters. Participants receive a scholarship to study abroad, where they conduct research on a topic that could improve some aspect of the local community in Japan. The study abroad component of this program lasts for three to four weeks during the summer break. The choice of destination for studying abroad varies and has included countries such as New Zealand, Thailand, and Canada in the past. To complete the program, students must participate in SALC-related activities, present on the topic that they researched while studying abroad, and score over 500 on the TOEFL standardized examination. Upon graduation, students participate in a small ceremony and receive a formal certificate of completion from the university president.

The program is designed for students to develop a global mindset so they can succeed and navigate in the highly interconnected and diverse global environment in the future. This includes being sensitive to other cultures, developing strong interpersonal communication skills, having the ability to adapt to new situations, and becoming competent speakers of English. According to the Department of International Education & Collaboration at Hirosaki University, Hayabusa College is, “…an educational program for first-year undergraduate students and above to develop the ability to play an active role in an increasingly globalized society” (Hirosaki University, n.d.). One key requirement for students enrolled in this program is participating in SALC activities such as attending seminars and the conversation space before and after studying abroad. In the next section, we describe how Hirosaki University’s SALC is integrated into Hayabusa College.

SALC and Hayabusa College: Two Key Factors

Hirosaki University’s SALC is an essential component of Hayabusa College as it prepares students for studying abroad before they leave Japan and provides them with opportunities to further develop their English skills after returning, as well as a place for them to share their experiences with other students. In this section, we will outline two key contributing factors of the SALC for Hayabusa College. First, the SALC provides a unique opportunity for students to gain a sense of studying abroad without leaving their home campus. Participating in SALC activities can enhance their study abroad experience by preparing them linguistically and culturally before traveling overseas. Additionally, the SALC aims to fulfill the basic psychological needs, as outlined in Self-Determination Theory (SDT, Ryan & Deci, 2017) and applied to a foreign language learning context (Birdsell, 2018). Fulfilling these needs has the potential to increase students’ intrinsic motivation to learn English.

The Importance of Being Prepared

One challenge faced by a curriculum that has a study abroad component is how to effectively prepare students to become proficient in English as an International Language (EIL) and navigate the subtle cultural, pragmatic, and other communication differences between countries in a limited amount of time. In the context of Hayabusa College, the goal is to prepare Japanese EFL students to study, interact with locals, and do research in either an Anglophone country (e.g., New Zealand or Canada) or an Asian country (e.g., Thailand) where EIL is used as the means of communication. Thus, preparing students to overcome the challenges of studying abroad is highly dependent on improving their English language proficiency and face-to-face communication strategies, such as gesturing, facial expressions, and using technology. In this regard, SALCs play a crucial role by offering students opportunities to practice these skills in a quasi-natural environment, simulating the experience of studying abroad. As a result, the SALC is tightly integrated into the Hayabusa College curriculum, and students are required to attend SALC activities both before and after studying abroad. In the current curriculum, there are three different types of activities they need to complete to fulfill the requirements of the program as outlined below:

(1) attend SALC seminars (ten 90-minute seminars prior to studying abroad and six 90-minute seminars after they return),

(2) visit the conversation space (participate in conversation activities five times before studying abroad), and

(3) select free activities (complete 10 free selection activities before and after studying abroad – e.g., attend a special lecture or seminar, visit the conversation space, participate in an advising session).

SALC seminars are held in a designated room within the facility. These seminars are conducted in English. Each week during the semester, there are two or three seminars offered each day. The topics of these seminars vary widely, ranging from content-specific subjects like psychology and European history to test-focused seminars (e.g., TOEIC, TOEFL). While the seminars follow the university schedule, they differ from traditional English classes in several ways: they are more flexible, have fewer students (usually one to 10 students), and are not driven by grades (e.g., there is no homework or tests). The primary aim of these seminars is to foster an atmosphere that encourages open dialogue and interaction between students and the teacher. These seminars are open to all students at the university, although Hayabusa students are required to attend them to complete the program.

In addition to these seminars, which focus mainly on academic English, Hayabusa students are also required to attend the conversation circle within the SALC. Each year a SALC teacher recruits and hires international exchange students to work in this space during their exchange program as an “EL Supporter”. This helps the exchange students feel included at the university while providing Japanese EFL learners with opportunities to enhance their English communication skills and engage with diverse cultures and World Englishes. Furthermore, since many of these exchange students come from non-Anglophone countries but possess high English proficiency, they can serve as motivation for the Japanese learners.

SALCs, as they mature at many universities, need to evolve and find ways to integrate more deeply within the university. The partnership between Hayabusa College and the SALC illustrates this need to adapt to the local demands. In the SALC, Hayabusa students have ample choices to choose and direct their own learning and gain confidence in themselves and how to navigate the challenges of using a foreign language in face-to-face communication with a wide range of interlocutors. Additionally, having Hayabusa students actively use the SALC can encourage other non-Hayabusa students to engage with the facility, as people are more likely to visit a place that seems lively and active rather than empty and unused. In summary, the SALC provides Hayabusa students with a variety of activities to develop their academic knowledge (e.g., seminars, special lectures, reading materials) and communication skills (e.g., conversation circle interactions). These activities prepare them for studying abroad and provide ongoing learning opportunities after they return to Japan.

Developing Learners’ Growth and Well-Being in an EFL Context

SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2000; 2017) is a broad theory of human motivation, behavior, and personality development. SDT includes a mini theory known as Basic Psychological Needs Theory (BPNT), which proposes that humans have three fundamental psychological needs for optimal growth and well-being: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Satisfaction of these needs, as opposed to frustrating or thwarting them, enables individuals to thrive and achieve their potential. Autonomy refers to having a sense of volition and choice, where one’s behaviors align with one’s interests. Competence is the feeling of efficacy and the overall capability to perform one’s actions. Relatedness is the feeling of being socially connected to others (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Some researchers have suggested a fourth need, a need for novelty, to be included in this set of basic psychological needs (e.g., González-Cutre et al., 2016). The need for novelty is the desire to experience something new or break from routine. In fact, Ryan and Deci (2000) consider intrinsic motivation to be the “inherent tendency to seek out novelty and challenges, to extend and exercise one’s capacities, to explore, and to learn” (p. 70).

SDT has been proposed as an overarching framework for future development of self-access language learning (SALL), as satisfying basic needs fosters language learning, growth, and well-being (Mynard & Shelton-Strong, 2022). In a SALC, students are encouraged to become autonomous learners by being given choices in how they develop their English skills. SALCs also provide learners with a sense of competency by allowing them to engage with the language in authentic situations. Frustration about meeting this need has been problematic among Japanese university students (see Birdsell, 2018), highlighting the importance of fostering learners’ confidence in their ability to use the language for communication. SALCs also support learners’ relatedness by offering a space to connect with a global community, including English teachers, international exchange students, and other Japanese students interested in global topics and foreign languages. If the need for relatedness is hindered, learners may feel excluded from the global English-speaking community or perceive their relation to English as superficial. For example, Garrett and Young (2009) examined the affective responses of a student in an 8-week Portuguese course and found that her sense of well-being improved after forming a group in class during the first week. This underscores how language serves as a social tool for communication, group identity, and a connection with others. As for the need for novelty, SALCs provide learners with numerous situations to experience something new, as they are designed to offer students a break from the routine of traditional classes. These flexible learning spaces provide individuals with opportunities to interact with exchange students from various countries, sparking their curiosity and encouraging exploration of new cultures and languages. Additionally, SALCs offer a wide range of diverse materials that align with students’ interests, such as graded readers, manga, board games, and academic periodicals.

In summary, the goal of SALCs is to create a learning environment where students can explore topics of personal interest, develop a stronger sense of competency to use the language in a natural environment, form friendships with others through the language, and broaden their curiosity to explore the unknown. Achieving these goals is expected to boost students’ motivation to learn English, improve their language skills, and strengthen their connection to both the language and the broader community of speakers. If Hayabusa students perceive the SALC as valuable, they are likely to continue using the space even after fulfilling the Hayabusa College requirements. However, this is not always the case, as many Hayabusa students stop utilizing the facility after completing the program. To better understand why one student has consistently continued to use the SALC, we analyzed the trajectory of a former Hayabusa student through an autobiographical narrative, focusing on how she navigated the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional aspects of learning English.

Method

Autobiographical Narratives

Autobiographical narratives are a common method for collecting data on the lived experiences of language learners (Pavlenko, 2007). This approach provides insight into the social, contextual, and idiosyncratic factors that influence language acquisition. Narrative inquiry provides researchers insight into the dynamic processes of learners’ struggles, motivations, and affective responses to learning a foreign language. As opposed to collecting data from scales (e.g., motivation questionnaire), classroom observations, or language performance assessment tools (e.g., TOEFL), narratives aim to “capture the nature and meaning of experiences that are difficult to observe directly and are best understood from the perspective of those who experience it” (Barkhuizen et al., 2014, p. 8).

In foreign language learning, autobiographical narratives are personal stories, reflections, and memories about various learning experiences both inside and outside the classroom. They allow individuals to construct their own identities. Using the individual learner as a storyteller provides a nuanced approach to understanding the language learning experience, the development of an L2 identity, and language socialization. Dewaele (2005) argues that the language learner is “a crucial witness of his or her own learning process” (p. 369), making this approach particularly valuable. This study follows the work of Garrett and Young (2009) in highlighting the under-researched area of affective responses to foreign language learning using an autobiographical narrative.

An Autobiographical Narrative From a Former Hayabusa Student

Saki, the second author, is currently a 4th-year student in the School of Clinical Psychological Science. A profile of her English education background began when she was 13 years old, like most Japanese students of her generation, in secondary school, where she took required English courses for six years. In 2021, she enrolled at Hirosaki University and, during her first year, took mandatory Liberal Arts English courses. Then, at the end of her first year, she applied and was accepted into Hayabusa College. In this program, during her 2nd year of university, she participated in a short-term study abroad program in Canada, conducted a research project on student counseling services offered at a university there and how to apply such a model to a Japanese university, achieved a TOEFL score of over 500, and completed the required SALC seminars and other SALC activities. In March 2023, she graduated from this program. In 2024, she received a 1-year government study abroad scholarship called Tobitate (see https://tobitate-mext.jasso.go.jp/about/english.html).

Brian, the first author, taught her seminars in the SALC and was also her advisor for the Hayabusa research project. He has been involved with Hayabusa College since its inception and has, over the years, observed many students lose interest in studying English and stop using the SALC after returning from their study abroad program. He has noted that these students typically move on to upper-level specialized courses in their faculties and become busy as they focus on completing their graduation theses. However, despite having most of her coursework at a separate medical campus, Saki continued to actively use the SALC and sought opportunities to improve her English communication skills, even after finishing the program. Brian became intrigued by her motivational trajectory and what drove her to persist with her English studies. Consequently, we decided to explore her English learning experiences and how they evolved over time by having her record an autobiographical narrative.

Over two separate time periods, she reflected on her English learning journey and created a chronological timeline of significant events. She began with her earliest memories, classroom experiences, interactions with others, and the emotional aspects of learning English. She also reflected on her experiences at Hirosaki University, her participation in the Hayabusa program, her experiences in the SALC, and her study abroad experience in Canada. To record her narrative, she used a mixed-language approach, incorporating both her L1 (Japanese) and L2 (English). This method allowed her to express herself more fluently while capturing the nuances of her experiences. Additionally, it reflects the multilingual nature of many language learners’ thoughts and emotions during cross-cultural and cross-linguistic experiences.

Brian reviewed her narrative, identifying key themes in the text. Then, these themes were collaboratively refined and adjusted as necessary. Additionally, some of the emerging themes were developed in greater depth. This was accomplished through unstructured interviews conducted during the review process.

Findings and Discussion

Beginnings

Saki’s first memories of English are watching foreign movies with her father. One thing she recalls is noticing a difference between Japanese and English in how feelings are expressed; she stated, “It was interesting for me that expressions of feeling are different between Japanese and English.” However, she had no real opportunity to use English in her daily life, she stated, “I didn’t have opportunities to speak English in classes,” and therefore, her speaking skills, at this time, were at a basic level for a high school student in northern Japan. She mentioned, in Japanese, that despite having a yearning to speak English, she did not study outside of class time 「英語を話すことに憧れはあったが,学校の授業以外の勉強はしなかった 」. The early exposure to watching movies in English with her father led to developing an interest in the language when she was in primary school. Later, in secondary school, she developed a desire to learn English but did not actively do anything special towards achieving her goal.

Transition to University and Hayabusa College

As Saki entered university, like so many students learning a foreign language, she worried about making mistakes and had self-doubt from comparing herself to others, as she states:

After entering Hirosaki University, I was placed in the higher English class. I couldn’t participate in classes actively, because I worried making mistakes. I felt strongly other classmates are much better than me.

Despite worrying about making mistakes, she found “enjoyment” in studying English and this propelled her to try difficult writing activities, and she gained a sense of pride and satisfaction when she completed a well-written essay and received praise from her teachers and peers. However, she considered herself “one of the 普通の[1] students for this moment. I couldn’t expect I applied Hayabusa and Tobitate and tried to study abroad.” Moreover, she struggled to communicate in the language and felt using it was a burden and tiresome.

And I felt like my brain didn’t work well in English compared to in Japanese. I thought it is the reason that I couldn’t come up with any questions to others and I couldn’t talk with fun. Sometimes talking with others in English is burden for me, particularly when I was tired.

Despite these struggles, she decided to enroll in Hayabusa College and was accepted into the program. As Hayabusa College requires attending activities in the SALC, Saki frequently visited the center before studying abroad. She liked attending seminars, as they were less stressful than the conversation space. She remarked, “I really like the seminars because they have a different atmosphere than my regular classes” 「普通の授業と違う雰囲気があってすごく好き」. She was soon able to make friends through visiting the SALC.

For now, I’m not afraid of going to the EL [SALC name] because there are many friends. I enjoy going there and talking with friends. I’m not good at talking even now. I’ve continued to go to the EL and eventually I became friends with many people including exchange students. I’m so happy.

Saki stated that she enrolled in Hayabusa College because she was informed that she would receive support from the professors and a financial scholarship to study abroad. She also indicated that she did not want to have any regrets at the end of her university life. The chance to study abroad was a transformative experience for her, as she began with a lack of confidence and, in the end ,felt like “I could do anything.” In addition, she had a positive experience during the study abroad program, as indicated below in the following passage from her narrative.

I studied abroad in Canada for a short time. It was my first time to go abroad, and I was very anxious because I was not confident in my English ability, but when I went there, I found that it was a lot of fun and I learned that I could survive in a foreign country. After studying abroad, I felt that I could do anything. It was like when I got a star in Mario Kart. (English translation)

「カナダに短期留学した。初めての海外で,英語力にも自信がなかったのでとても不安だったが,行ってみると楽しいことばかりで,案外海外でも生きていけることを知った。留学したあとは,自分なら何でもできるように感じた。マリオカートでスター取った時みたいに。」

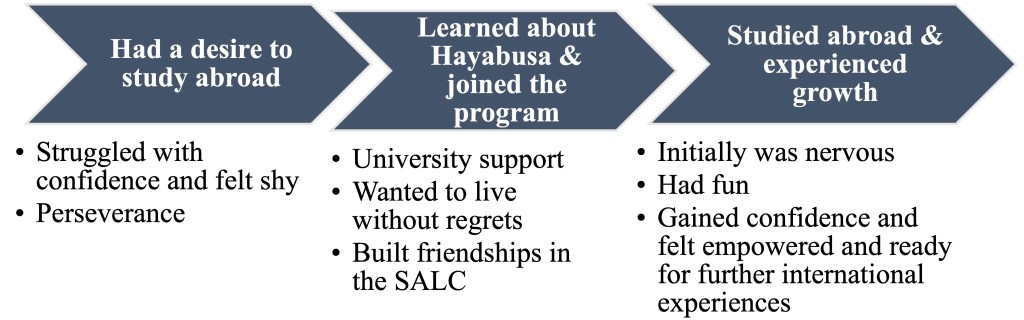

Figure 1 shows the transition she went through from her desire to study abroad, the negative emotions she struggled with, and then the confidence she gained from participating in the program.

Figure 1

Transition to University and Hayabusa College

Upon returning from her short-term study abroad experience in the Hayabusa program, she still had to overcome the emotional challenge of using a foreign language, which included self-doubt and anxiety. To maintain her interest, she engaged herself in numerous cultural experiences on campus, such as visiting the SALC and joining other international programs. One key factor in her determination to continue using and learning English was its relevance to her academic interest in researching animal-assisted therapy.

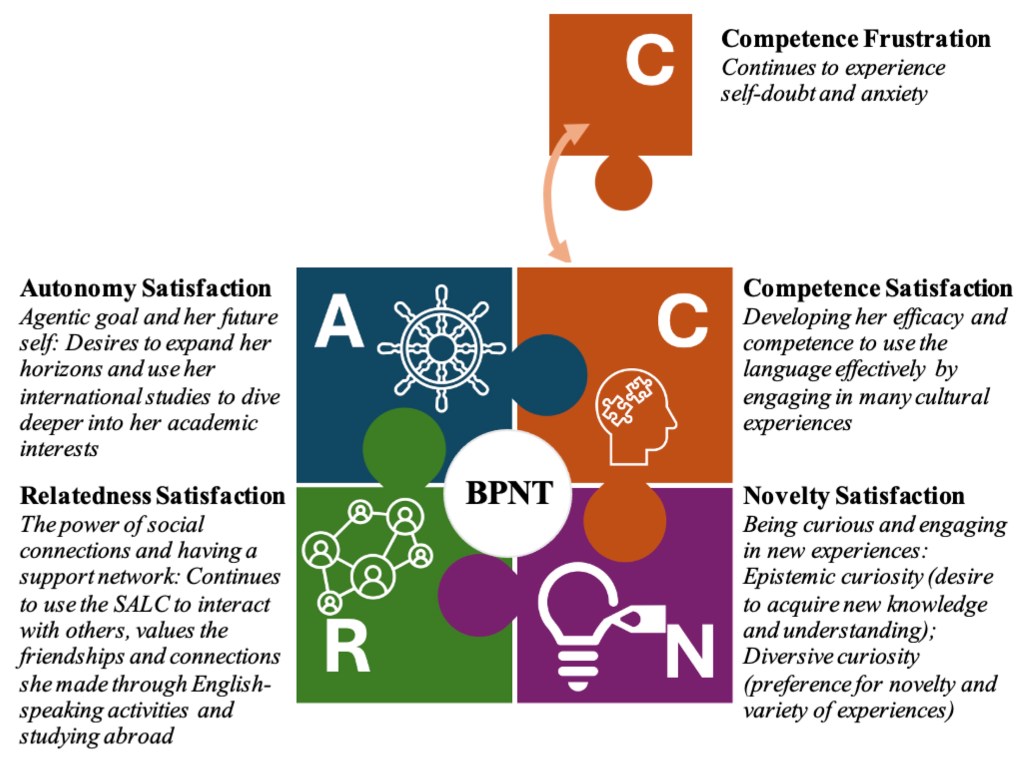

Satisfaction and Frustration of Basic Psychological Needs in an EFL Context

SALCs are complex, social learning spaces (Murray, 2013; Thornton, 2020), and there are many psychological barriers that students face when entering a SALC. In this section, we use BPNT as a framework to analyze Saki’s autobiographical narrative. We will organize this section using the basic psychological needs.

Firstly, regarding satisfying the need for autonomy, this was evident in Saki’s narrative when she discussed her future and academic pursuits. Her responses were self-directed, as she made her own decisions and took the initiative in setting her academic goals. She envisions her “future self” pursuing Animal Assisted Therapy (AAT), which requires English proficiency and cultural knowledge from overseas, mainly because AAT is not yet widely practiced in Japan.

I’m studying Animal Assisted Therapy (AAT) but it’s not common in Japan. There is less research about it in Japan. So I decided to study abroad to learn AAT more deeply.

She has a strong desire to help society by improving the mental health and well-being of Japanese and non-Japanese people. She is also aware of the changing demographics in Japan and the need for therapists to be able to communicate with foreign populations living in Japan. This includes permanent residents but also those who come for short-term work or study abroad experiences. At the same time, she is not isolated nor working individualistically towards this goal but has a sense of gratitude for support and guidance. Finally, she actively envisions using English in her future, as she states, “Anyway I want to use English actively in my future job,” and this future L2-self (see Dörnyei, 2009) drives her motivation to continue engaging with English in various situations.

Secondly, competence frustration is when the individual perceives that one is incapable of achieving the desired outcome of some task (Ryan & Deci, 2017). In the context of this study, this likely includes using English for communication in an unstructured environment like a SALC. This frustration may stem from various factors such as a lack of skill, unrealistic expectations (e.g., must be fluent to use the language), or having received constant negative feedback in the past (e.g., low test scores). Repeated experiences of competence frustration likely result in lower motivation to engage in a specific task. In a previous study (Birdsell, 2018) with Japanese participants using a 6-point Likert scale, the results show that competence frustration (4.48) is considerably higher than frustration for other basic psychological needs such as autonomy (3.61), relatedness (3.31), and novelty (3.65). Additionally, this is the only need where frustration scored higher than satisfaction. As for Saki, this also was one of the major challenges she faced. She struggled with the belief that she did not have the competence to use English in a setting like a SALC and this led to negative affective states such as heightened anxiety and self-doubt. However, she did attempt to overcome this by engaging in many different international and cultural activities both in and outside the SALC and this gradually improved her sense of competency.

Thirdly, the need for relatedness, Saki expressed finding a community of speakers such as exchange students, Japanese students, and teachers who all share her interest in languages and learning about other cultures. She described how the SALC provided her with opportunities to develop friendships, which she values. When discussing motivation, the self is often the central focus, which overlooks the role of social motivation. Results from this study show that the group or social environment and relationships developed in this social space play a major role in motivating behavior to perform some action (e.g., visit the SALC, go abroad). Saki used this expression when discussing why she decided to join a long-term study abroad program, 「類は友を呼ぶ 」. This idiom loosely means “influenced or encouraged to do something by your peers.” It can have both negative and positive meaning. In her case, it has a positive meaning. Through participating in Hayabusa College and becoming a regular user of the SALC, she developed friendships with a group of other students with similar interests (e.g., foreign cultures, English language, studying abroad, etc.). Then, being around these friends, as she stated, “it is just natural to want to study abroad.”

Finally, the need for novelty. Novelty fosters curiosity through the unfamiliar and new, prompting exploration and engagement with this new information. This occurs both with exploring to learn and exploring to experience new situations. This first appeared in her writings when she described her childhood. She developed a sense of curiosity for the unfamiliar and novel, and this continued as she entered university. She became more curious about foreign cultures and linguistic expressions, especially in learning English idioms and metaphors such as “it’s not my cup of tea” and “get the ball rolling.” Moreover, she wanted to have access to information and cultural knowledge that was not readily available in Japanese. She also discussed how she viewed English as a gateway to discovering new ideas for her research topic. This type of curiosity is referred to as “epistemic curiosity,” which is the desire for new knowledge and to explore academic environments (Grossnickle, 2016). This type of curiosity sustains interest over time (Silvia, 2006) and motivates the individual to be inquisitive (Berlyne, 1954). Another type of curiosity is “diversive curiosity,” which is seeking uncertainty and a variety of unfamiliar and novel experiences to alleviate boredom (Spielberger & Starr, 1994). Saki showed this when she sought out new and unfamiliar opportunities to meet people from foreign countries and to further pursue uncertainty by applying to Tobitate.

Figure 2 outlines the four basic psychological needs with a summary for each one. Satisfaction of these needs appeared in the narrative data. Regarding frustration, only competence frustration appeared.

Figure 2

Satisfaction and Frustration of the Basic Psychological Needs from the Autobiographical Narrative

Limitations

As with any study that uses a single autobiographic narrative, there are a couple of limitations that need to be stated. Firstly, the results presented here are not generalizable but rather reflect a single individual’s unique experiences learning English, studying abroad, and using a SALC. Secondly, the narrative has the potential to include personal biases based on selective memory of past events. Moreover, the possibility of omitting details or experiences might have resulted in gaps in the narrative and reliability of the data. Nevertheless, the findings of this study suggest the importance of conducting research that examines the lived experiences of students as they progress through their journey toward learning English. This includes their prior experiences, their current situation, and their motivations (or lack thereof) to continue this journey. Studying abroad plays a crucial role, but finding opportunities to interact with people in a quasi-natural English environment, like a SALC on their home campus, also plays a significant role. This study focused on a student who continued to use the SALC after completing the requirements for Hayabusa College. To understand the reasons more deeply why some students lose motivation and interest, future research could examine a student who does not use the SALC after completing the program.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this article first introduced a special study-abroad scholarship program at Hirosaki University called Hayabusa College and how the SALC at the university has been integrated into this program. Then, using autobiographical data from the second author, a student on the program, we explored her experiences as a frequent SALC user to understand her motivation to continue to use the facility for language learning. By applying BPNT as a framework to her narrative, we identified the satisfaction of meeting her needs for autonomy, competence, relatedness, and novelty. The only frustration she expressed was related to her need for competence, which involved personal struggles with anxiety and low self-efficacy. Thus, SALCs must consider how to satisfy the need for competence among students by providing them with opportunities and activities in a supportive environment that focuses on communication and growth rather than perfection and striving toward becoming an idealized “native” speaker. The main point here is that entering the SALC can be intimidating and difficult for many students, and this is not due to a lack of interest in the facility nor a lack of desire to improve one’s English skills but rather due to past experiences that have resulted in the frustration of the individual’s perceived competency with the language.

To return to the introduction, at the heart of a SALC is the root of the word “educate;” it is a place to nurture students so they can grow. It is not about filling them with knowledge but instead providing them opportunities to interact with others and challenge themselves with the goal of developing and reaching their potential.

Notes on the Contributors

Brian Birdsell received a Ph.D. in Applied Linguistics from the University of Birmingham, UK and currently is an Associate Professor in the Institute for the Promotion of Higher Education at Hirosaki University. He teaches in the university SALC and liberal arts classes. His research interests include metaphor, embodied cognition, creativity, and CLIL.

Saki Niioka is a 4th-year undergraduate student in the School of Clinical Psychological Science at Hirosaki University. She is currently researching animal-assisted therapy. She also received a “Tobitate! Study Abroad Initiative” scholarship from The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) to study in Canada and the USA for 9 months in 2025.

References

Barkhuizen, G., Benson, P., & Chik, A. (2014). Narrative inquiry in language teaching and learning research. Routledge.

Berlyne, D. E. (1954). A theory of human curiosity. British Journal of Psychology, 45, 180–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1954.tb01243.x

Birdsell, B. J. (2018). Understanding students’ psychological needs in an English learning context. Journal of Liberal Arts Development and Practices, 2, 1–14.

Cushner, K., & Mahon, J. (2002). Overseas student teaching: Affecting personal, professional, and global competencies in an age of globalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 6, 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315302006001004

Dewaele, J. M. (2005). Investigating the psychological and emotional dimensions in instructed language learning: Obstacles and possibilities. The Modern Language Journal, 89(3), 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2005.00311.x

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. In Z. Dörnyei, & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9–42). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847691293-003

Fryer, M., & Roger, P. (2018). Transformations in the L2 self: Changing motivation in a study abroad context. System, 78, 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.08.005

Garrett, P., & Young, R. F. (2009). Theorizing affect in foreign language learning: An analysis of one learner’s responses to a communicative Portuguese course. The Modern Language Journal, 93(2), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00857.x

Gmelch, G. (1997). Crossing cultures: Student travel and personal development. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 21(4), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(97)00021-7

González-Cutre, D., Sicilia, Á., Sierra, A. C., Ferriz, R., & Hagger, M. S. (2016). Understanding the need for novelty from the perspective of self-determination theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.036

Grossnickle, E. M. (2016). Disentangling curiosity: Dimensionality, definitions, and distinctions from interest in educational contexts. Educational Psychology Review, 28(1), 23–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-014-9294-y

Hirosaki University (n.d.). HIROSAKI Hayabusa College. Department of International Education & Collaboration, Hirosaki University. Retrieved from https://www.kokusai.hirosaki-u.ac.jp/en/studyabroad01/sa01_page9/

Maddux, W. W., & Galinsky, A. D. (2009). Cultural borders and mental barriers: the relationship between living abroad and creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1047. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014861

Murray, G. (2013). Pedagogy of the possible: Imagination, autonomy, and space. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 3(3), 377–396. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2013.3.3.4

Mynard, J., & Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2022). Self-determination theory: A proposed framework for self-access language learning. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning, 4(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.52598/jpll/4/1/5

Pavlenko, A. (2007). Autobiographic narratives as data in applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics, 28(2), 163–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amm008

Pearce, P. L., & Foster, F. (2007). A “university of travel”: Backpacker learning. Tourism Management, 28(5), 1285–1298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.11.009

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

Silvia, P. J. (2006). Exploring the psychology of interest. Oxford University Press.

Spielberger, C. D., & Starr, L. M. (1994). Curiosity and exploratory behavior. In H. F. O’Neil Jr., & M. Drillings (Eds.), Motivation theory and research (pp. 221–243). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Thornton, K. (2020). The changing role of self-access in fostering learner autonomy. In M. Jiménez Raya & F. Vieira (Eds.) Autonomy in language education: Present and future avenues (pp. 157–174). Routledge

Williams, T. R. (2005). Exploring the impact of study abroad on students’ intercultural communication skills: Adaptability and sensitivity. Journal of Studies in International Education, 9(4), 356–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315305277681

[1] This is a direct quotation where she mixed the languages. 普通の[futsu no] translates as “normal,” “typical,” “ordinary”