Thi My Linh Tran, Department of Education and Human Potentials Development, National Dong Hwa University, Hualien, Taiwan, and Faculty of English, Thuongmai University, Vietnam.

Tran, T. M. L. (2025). Teachers’ beliefs about learner autonomy in collaborative online learning: Insights from a university in Vietnam. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(1), 100–122. https://doi.org/10.37237/202405

Published online first on 22 November 2024.

Abstract

This article aims to explore teachers’ perspectives about learner autonomy (LA) and specifically, it explores how collaborative online learning (COL) may aid English language teachers at a Vietnamese university in fostering students’ capacity for LA as part of their instructional approach. This mixed methods paper presents the findings obtained from an online questionnaire and individual interviews with 47 teachers from a Vietnamese university. The results show technical, psychological, and political interpretations of autonomy in language education, which reveal two distinct yet interrelated perspective of autonomy among teachers: independent and interdependent learning. Furthermore, the research demonstrates the role of language teachers in COL and identifies some limitations pertaining to the promotion of autonomy in virtual classrooms.

Keywords: learner autonomy, teacher autonomy, collaborative online learning, teachers’ beliefs

Beliefs play an important role in language teaching, as they shape teachers’ perceptions and evaluation of language pedagogy (Borg, 2001; Klapper, 2006). The beliefs of language teachers are influenced by their personal characteristics and previous experiences as both learners and teachers (Donaghue, 2003), which can influence their own thoughts and actions (Pennington, 1996). As a result, ELT educators should be aware of the importance of personal beliefs in their continuous professional development (Donaghue, 2003). This awareness is closely tied to the concept of autonomy, a recurring theme in ELT studies, as both teachers and learners benefit from developing greater autonomy in the learning and teaching process. The way teachers understand the concept of autonomy is likely to be linked to their own learning experiences, as it may be challenging for them to fully believe in something they have not personally experienced (Ramos, 2016). Therefore, Smith (2000) argues that the capacity for autonomy is a prerequisite for language teachers, just as it is for language students. Different studies have shown that the teaching context is influential in the construction of teachers’ beliefs as it shapes their experiences, challenges, and access to resources, which in turn affect their instructional practices and perceptions (Borg, 2003; Phipps & Borg, 2009), including in computer-assisted language learning (CALL).

CALL is an area of applied linguistics has increasingly focused on the advancement of independent learning. Reinders and Hubbard (2013) contend that CALL not only assists language learners in gaining more control over their own learning process but also provides teachers with additional opportunities (e.g., online platforms) to engage with their students, such as through online platforms. This means that CALL can be a great affordance through which learners can develop their autonomy. However, as Hamilton (2013) argues, the concept is challenging to define, operationalize and evaluate, especially in online learning environments. Many teachers and students still perceive autonomous learning as an individual endeavor carried out outside the classroom using mobile phones or computers. Elliott (2016) asserts that this misguided assumption has distorted the true nature of autonomous learning and the impact of technology on language learning.

It goes without saying that the numerous face-to-face language teaching practices have transitioned to virtual classrooms due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Nambiar, 2020; Zhang, 2020). There is a pressing need for linguistic researchers to conduct further investigations into autonomous learning and the integration of technology to foster collaboration in virtual learning, particularly from the perspective of ELT teachers, not only due to the shift caused by the COVID-19 pandemic but also because of the increasing reliance on online education and the ongoing digital transformation in language teaching. While the pandemic accelerated the adoption of virtual classrooms, the broader gap lies in understanding how ELT teachers can effectively develop learner autonomy and collaboration in these digital environments, which remains underexplored in current research.

The subject of ELT teachers’ beliefs on autonomous learning has received limited attention in previous research (Borg & Al-Busaidi, 2012). The authors argue that understanding the perspectives of language instructors on autonomy is considered a vital factor in the advancement of learner autonomy. Nevertheless, the optimal strategy for enhancing teacher capacity remains a topic of ongoing inquiry (Benson & Huang, 2008). Benson & Huang (2008) describe that the development of autonomous capacity cannot be imparted by instruction, but rather is learned through the experiential process of self-direction in substantial domains of learning. Alternatively, it has been proposed that the notion of teacher autonomy (TA) encompasses the inclination to provide opportunities for professional autonomy within one’s own work setting (Benson & Huang, 2008).

Orsini-Jones et al. (2017) state that there appears to be a lack of awareness among ELT practitioners about the substantial influence that their beliefs exert on their instructional methods. Teacher views might serve as an impediment or a selective mechanism while striving to advance their own professional knowledge and teaching (Klapper, 2006). Additionally, it is worth noting that instructors’ own learning experiences can have a significant impact on their instructional practices (Richards & Lockhart, 1994).

Scholars such as Benson (2000), Dörnyei (2001), Littlemore (2001), and Illes (2012) have put forth the argument that the utilization of technology in teaching is deemed highly suitable for the advancement of LA. In addition, Orsini-Jones (2015) characterizes online learning as a dynamic interplay between collaborative efforts and individual autonomy. There has been restricted research examining the significance of LA in relation to instructors (Phi, 2019; Yuzulia, 2020). Therefore, the present study addresses this gap by identifying teachers’ beliefs in collaborative online environments. It aims to investigate the perceptions of lecturers, including both novice and experienced lecturers, regarding the concepts of LA and COL in the context of computer-mediated classrooms as a temporary alternative to regular classes during the COVID-19 outbreak at a Vietnamese university. Furthermore, it highlights lecturers’ perspectives regarding the role of them in COL as well as some constraints in fostering the autonomous capacity at tertiary education level in Vietnam.

Literature Review

Learner Autonomy and Teacher Autonomy in Language Education

Holec (1981) defines autonomy as the capacity to assume responsibility for one’s own learning. Little (1991) states that autonomy may be understood as including a broader range of abilities, including the ability for detachment, critical thinking, decision-making, and autonomous action. The concept of autonomy is employed to characterize educational contexts (Benson, 2007). Dickinson (1987) claimed that autonomy is defined as the state in which the learner assumes complete responsibility for all decisions related to their learning and the subsequent execution of those decisions. While there is ongoing scholarly debate on the necessary degrees of freedom in the development of LA, it is widely acknowledged that autonomy should not be equated with the concept of freedom in the context of language learning (Little, 1996).

The concepts of autonomy, independent learning, autonomous learning, and independent study are frequently employed interchangeably by professionals and in certain scholarly works to denote a fundamentally similar phenomenon (Holmes, 2021). However, the concept of LA cannot be clearly defined as a singular behavior or a specific combination of behaviors (Little, 1981, as cited in Holmes, 2021). The construct in question is characterized by its multidimensional nature, impacting several elements (Reinders & White, 2016), and exhibiting a multitude of distinct and frequently ambiguous interpretations. Benson (1997) classifies LA into three perspectives: (1) a technical perspective that focuses on the skills and strategies that learners should be able to carry out to succeed in unsupervised learning situations; (2) a psychological perspective that considers the attitudes and cognitive abilities that allow learners to take responsibility for their own learning process and (3) a political perspective that empowers students to take control over their own learning.

The concept of autonomy is commonly linked to the adoption of a personalized approach to language acquisition. Geng (2010) points out the term “individual autonomy” is proposed as an alternative name for the notion. This term refers to the ability of an individual to independently guide, oversee, assess, and adjust their own actions and decisions. The aforementioned definition seems to presuppose those learners are the sole actors accountable for making decisions pertaining to their learning, as elucidated by Dickinson (1987). In contrast, Little (2007; 2016) highlights that LA surpasses the potential for personal self-guided learning. The development of knowledge occurs via deliberate engagement with educators and fellow learners (Little, 2001). Collaboration is a significant component of autonomy, as students engage in cooperative efforts and assume shared accountability for their educational pursuits. Benson (2001, 2013) highlights that autonomy in language learning is not only about individual control but also involves the capacity to collaborate, reflect, and engage in shared responsibility. His definition aligns with the notion that autonomy involves not just personal management but also collaborative processes, where students actively work together and take joint responsibility for their educational progress. This collaborative dimension emphasizes that autonomy thrives in environments where learners can exchange ideas, support one another, and collectively navigate their learning journey.

The process of autonomy necessitates both the ability for introspection (Little, 2016; Sinclair, 2000) and a reconfiguration of the responsibilities held by educators and learners (Geng, 2010). TA was formally established by Little (1995) during the mid-1990s, and Ramos (2016) claims that there is a belief that TA and LA are contemporaneous. The concept TA involves the teacher’s independent ability to study and guide their own educational process in teaching language. If teachers are not provided with the chance to engage in autonomous learning, they may have challenges in cultivating autonomy (Benson & Huang, 2008). While some argue that eliminating constraining teaching styles, such as authoritarian management, is necessary for fostering autonomy in English teaching and learning (Geng, 2010), it is important for teachers to retain a certain level of authority to effectively guide the students’ process of becoming autonomous (Ramos, 2016).

Teachers’ Role and Beliefs about Learner Autonomy in Collaborative Online Learning

Teachers play a crucial role in facilitating the development of learner self-regulation (Ellis & Shintani, 2014), and their beliefs about LA can influence the extent and methods by which they facilitate its advancement. The ability to self-regulate enables independent learners to effectively control, oversee, and assess their own learning process (Little, 2001). Therefore, the transfer of autonomy to educational settings has garnered more focus on educators (Benson, 2007). Nevertheless, Benson concludes that the necessity for teacher assistance may potentially become a pressing issue that facilitates the growth of this capability.

Ramos (2016) argues that the concept of autonomy in education does not entail a complete relinquishment of control and decision-making by instructors to learners. L2 learners continue to require teacher cooperation to develop autonomy, as evidenced by the growing notion of COL, which encompasses many approaches to teaching and learning (Benson, 2007). Furthermore, Littlemore (2001) states that while the presence of technological advancements may facilitate different forms of self-directed learning, it is not a guaranteed outcome. The potential danger of substituting reliance on teachers with reliance on machines should be duly considered (Littlemore, 2001).

Teachers’ beliefs about online environments are multifaceted and significantly influence their adoption and integration of digital technologies in educational settings. These beliefs are shaped by various factors, including personal attitudes, self-efficacy, and professional development experiences. Understanding these beliefs is crucial for fostering effective online teaching practices. Positive attitudes are associated with increased use of technology, while negative attitudes can hinder its adoption. For instance, foreign language teachers in Serbia with positive attitudes towards ICT are more likely to incorporate digital tools into their teaching, enhancing the learning experience (Vidosavljević, 2023). Conversely, university teachers often exhibit more negative attitudes towards digital environments compared to their counterparts in primary and secondary education, highlighting the need for targeted training to improve their perceptions (Vidosavljević, 2023). Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted teachers’ beliefs about online learning, emphasizing the importance of motivation, engagement, and social relationships in virtual settings (Ishak et al., 2023).

The subject of ELT teachers’ beliefs on autonomous learning has received limited attention in previous research (Borg & Al-Busaidi, 2012). The authors argue that understanding the perspectives of language instructors on autonomy is considered a vital factor in the advancement of learning autonomy. Nevertheless, the optimal strategy for enhancing teacher capacity remains a topic of ongoing inquiry (Benson & Huang, 2008). Benson & Huang (2008) describe that the development of autonomous capacity cannot be imparted by instruction, but rather is learned through the experiential process of self-direction in substantial domains of learning. Alternatively, it has been proposed that the notion of TA encompasses the inclination to provide opportunities for professional autonomy within one’s own work setting (ibid.).

Orsini-Jones et al. (2017) state that there appears to be a lack of awareness among ELT practitioners about the substantial influence that their beliefs exert on their instructional methods. Teacher views might serve as an impediment or a selective mechanism while striving to advance their own professional knowledge and teaching (Klapper, 2006). Additionally, it is worth noting that instructors’ own learning experiences can have a substantial impact on their instructional practices (Richards & Lockhart, 1994).

Therefore, this study aims to explore learner autonomy as perceived by English language teachers at a Vietnamese university and explore how virtual learning can influence teachers’ perspectives regarding COL to promote a student-centered pedagogical approach.

Research Questions

The study reflects on the nature of LA in COL practice in the field of ELT teacher cognition. It addresses the following research questions:

- How do English teachers perceive LA and collaborative language learning in the virtual exchange era?

- What are teachers’ self-perceived roles in developing learner autonomy?

- What are some factors which may prevent the implementation of LA in COL?

Methods

Participants

This mixed-method research was carried out with was carried out with 47 participants (Table 1), working at a university in Vietnam. They were aged between 25 and 50, had from less than 1 year to more than 10 years of teaching experience at the tertiary level, and from half of year to more than 2 years of teaching experience in online environments. All the participants gave informed consent to participate in the study voluntarily. The diverse nature of this sample allowed for the exploration of various individual differences in participants’ beliefs on autonomy and COL. These differences included factors such as prior learning context, age, gender, and teaching experience. Conversely, qualitative instruments were designed to describe the specific elements that make up a unique experience (Polkinghorne, 2005). Table 1 below provides details on the demographics of the participants who all gave informed consent.

Table 1

Demographics of the Survey Sample

Instruments and Procedures for Data Collection

This study made use of two research instruments: a questionnaire and an individual interview. Firstly, an online questionnaire was used to engage participants individually in a meta-reflection in terms of the three research questions. This instrument is likely to be one of the most popular methods of collecting data within a short period of time (Mackey & Gass, 2005). Participants were asked to respond to an online questionnaire containing items related to teachers’ beliefs about learner autonomy in collaborative online learning based on a 5-point Likert scale, such as whether autonomy is essential in ELT, whether teachers’ beliefs may impact the promotion of autonomy, and learners need teacher support to gain some level of autonomy. The data-gathering process was divided into four phases: questionnaire design, pilot, delivery, and data encoding. The second method used was individual interviews, which is often seen as the most common technique in qualitative inquiries (Dörnyei, 2007). The participants were asked questions related to learner autonomy, like the definition of learner autonomy, whether they think autonomy is a concept that is only suitable for Western culture, and teaching context may restrict their teaching practice or not.

Procedures for Data Analysis

The researcher created the questionnaires and strategies for data collection in the first phase. The questionnaire was distributed to roughly 5 participants to get comments and determine the usability. After the corrections and changes, it was delivered to each respondent with a consent form that explained the study aim and purpose. Finally, it was crucial to encode the data to explore the pertinent content to the subject which was determined by synthesizing and analyzing. The collected data was imported into appropriate tools (Microsoft Word and Microsoft Excel) to identify salient patterns, then analyzed by the mean of descriptive analysis. The heterogeneous nature of the quantitative sample allowed this study to gain several idiosyncratic individual differences (Dörnyei, 2007) regarding participants’ beliefs on autonomy and COL, providing different attributes related to prior learning context, age, gender, and teaching experience (Silverman, 2014). Qualitative instruments, on the other hand, were directed at describing the aspects constituting an idiosyncratic experience (Polkinghorne, 2005).

In gaining more insight into the quantitative findings, 10 teachers who could potentially provide more information were then selected to be involved in semi-structured individual interviews. Interview investigation consists of thematizing, planning, conducting the interview, transcribing, analyzing, confirming, and reporting. Prior to the interviews, the researcher created the study’s objectives and outlined the topic. The study design was then established with a focus on gaining the desired information. The interviews were semi-structured and lasted between 15 to 20 minutes each. It was conducted in Vietnamese and all interviews were recorded with the participants’ consent and later transcribed. The transcripts were carefully converted from oral speech to written text, ensuring accuracy and clarity. The data was then analyzed through content analysis, specifically focusing on themes related to learner autonomy. The interview data underwent multiple stages of validation to ensure reliability and generalizability. First, small sections of the transcribed text were highlighted and systematically categorized into themes that aligned with the study’s focus on learner autonomy. The categorized data was then interpreted to uncover patterns and beliefs about how teachers perceive and foster learner autonomy in their teaching practices.

Findings

Teachers’ Beliefs of Learner Autonomy and Collaborative Learning

The survey results revealed a strong consensus on the importance of autonomy in ELT. A significant majority of respondents, over 80%, strongly agreed that autonomy plays a crucial role in ELT. Additionally, a smaller portion, around 10%, mostly agreed with this statement. Only a minimal percentage of respondents neither agreed nor disagreed, while there were no participants who expressed disagreement with the idea.

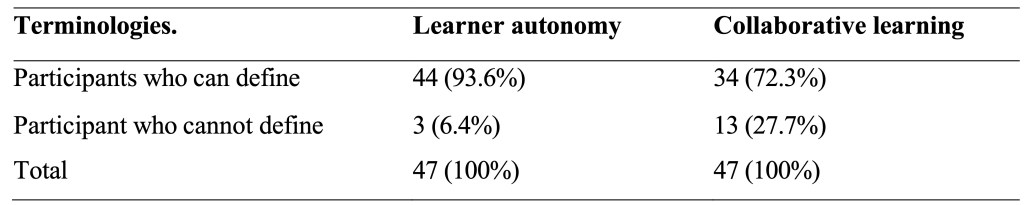

However, the level of comprehension of the concepts of LA and collaborative learning differed among the ELT teachers who took part in the study. As Table 2 shows, 93.6% of the participants were able to give a clear explanation of the concept of LA, while 6.4% of the survey sample did not fully comprehend what LA is, which is similar to what Elliot (2016) found in his/her investigation. Therefore, this prompts an additional inquiry regarding the ability of TA. If lecturers are unable to define genuine autonomy themselves, should they assert that it is being cultivated in their own teaching practice, as stated in statement 26 of “Am I an autonomous teacher?” All three English lecturers (Participants 28, 29, and 30) identified themselves as independent educators. It is probable that some lecturers who endorsed the perspective of “individual” autonomy still find the concepts of autonomy to be problematic knowledge (Geng, 2010). This could be due to the complex and multifaceted nature of learner autonomy, which requires a shift in traditional teaching practices and roles. LA was described by participants in various ways in the online survey. Participant #29 defined LA as “the learner’s attention and participation outside their classes,” while Participant #30 viewed LA as “the motivation of self-study at home.”

72.3% of the lecturers participating in the online survey demonstrated comprehension of the concept of collaborative learning, while 27.7% of those who failed to provide a clear explanation understood it. For example, while for Participant #6, “collaborative learning is the interaction in learning with teachers and among learners”, Participant #39 described it as “study at home”. Participant #29 highlighted that it “includes both face-to-face classroom and online learning,” whereas Participant 45 referred to it as “an e-learning technique in which more people can join in an educational course,” and Participant 46 associated it with “learning with instructions.”

There were some teachers who could not distinguish between cooperation and collaboration. Participant #5 stated, “Collaborative learning means cooperation in learning,” and similarly, Participant #21 explained it as “cooperate, group work.” Moreover, Participant #23 elaborated on this by describing collaborative learning in group assignments, where “students negotiate to divide up the task that each person needs to prepare their part before the whole group puts the pieces together into a complete work.”

Table 2

Results From Questions 11-12 of the Online Survey

In addition, there were some participants who could not explain briefly their understanding of both LA and collaborative learning terminologies. For instance, participant #29 described LA as “the learner’s attention and participation outside their classes” and defined collaborative learning as something that “includes both face-to-face classroom and online learning.”

Most participants concurred that teachers’ beliefs could have an impact on the development of autonomy in ELT. The survey data indicates that nearly half of the respondents, around 45%, strongly agree that teachers’ beliefs may impact the promotion of autonomy. An additional 45% mostly agree with this statement, demonstrating a broad consensus. A smaller proportion, about 10%, neither agreed nor disagreed, while only a negligible percentage expressed any form of disagreement.

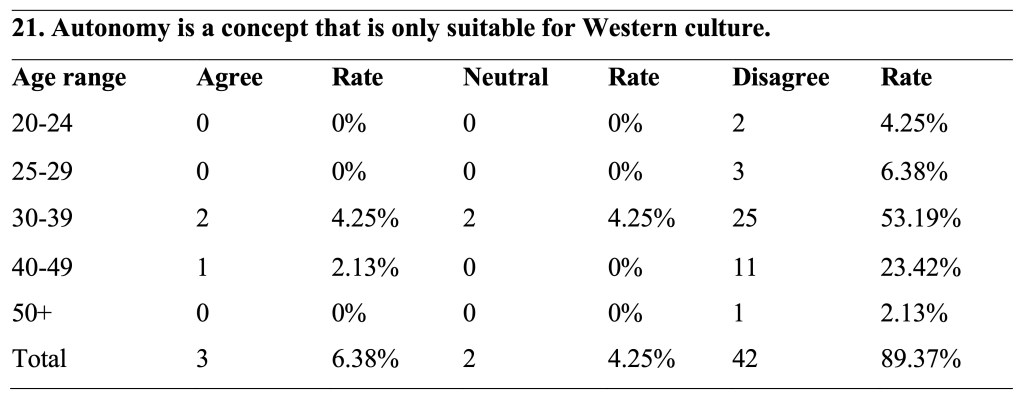

Moreover, the agreement regarding the psychological perspective (Benson, 1997) likely provided a clear explanation for the lecturers’ endorsement of both statements 21 and 27 (see Table 3).

Table 3

Results From Question 21 of the Survey

As Table 3 shows, a total of 3 out of 47 participants indicated their agreement with question 21. Richards and Lockhart (1994) state that teachers’ beliefs are focused on the specific language learning and teaching experience in a particular context. The beliefs of these participants appeared to be associated with the collectivist culture in the Asian context, where teachers are perceived as knowledge providers or authoritative figures.

According to Donoghue (2003), teachers’ beliefs are influenced by their personal traits and previous experiences as both students and educators. The findings from one-on-one interviews with the lecturers align with the perspective proposed by Benson & Huang (2008) that if teachers do not have the chance to learn independently, they are less inclined to promote independent learning in their teaching. For example, Participant #22 reflected on her university experience, explaining that “the most popular teaching method was teacher-centered approach,” where “the educator does almost all the talking while students continue to listen and remain silent.” Similarly, participant #39 emphasized the challenge of promoting autonomy in Vietnamese universities, noting that “students at universities in Vietnam are more familiar with that style of teaching because they have been with it since primary school when students usually put all of their focus on the teachers.” This makes “developing autonomous capacity in ELT classes at Vietnamese colleges very difficult.”

The interdependency between the LA and TA was also understood by almost all teachers. The results from question 25 of the online survey indicate that most respondents believe it is crucial for ELT teachers to develop their own capacity for autonomy before promoting it to their students. Specifically, over 50% of participants strongly agreed with this statement, while around 30% mostly agreed. A smaller percentage, about 10%, neither agreed nor disagreed, and only 3% expressed disagreement. This result is in a similar vein to what Smith (2000) advocates, that autonomous capacity is a prerequisite for language teachers as we consider it to be for language students.

The second most supported perspective was autonomy as a political orientation (Benson, 1997) underlined in statement 22. The learners are not thwarted by institutional choices (Ciekanski, 2007) in having the freedom to make decisions (Borg & Al-Busaidi, 2011). The majority of participants agree that autonomy in ELT does not mean teachers should completely transfer all control and decision-making to learners. Over 50% of respondents strongly agreed with this statement, while about 35% mostly agreed. A small percentage, around 5%, neither agreed nor disagreed, and almost no participants expressed any disagreement.

Roles of Teachers in COL to Develop the Autonomous Capacity for Learners

The lack of endorsement for the political viewpoint of LA (Benson, 1997) was also emphasized by the agreement regarding the technical aspect of autonomy in statement 23. It indicates that a significant portion of respondents believe that learners still require support from ELT teachers to develop some level of autonomy. Approximately 60% of participants strongly agreed with this sentiment, while around 30% mostly agreed. A very small percentage neither agreed nor disagreed and strongly disagreed. These perspectives not only encompass two main categories of teachers’ understanding of autonomy (independent learning and interdependent learning) but also highlight the teachers’ role in facilitating learners’ autonomy.

Little (1991) identifies two common misunderstandings about autonomy: (1) the belief that autonomy is the same as self-instruction, and (2) the misconception that in the classroom, learner autonomy requires the teacher to give up all initiative and control. Little (1994) contends in a separate investigation that our independence as social beings is consistently counterbalanced by our dependence, and our fundamental state is one of interdependence. According to Littlemore (2001), Borg & Al-Busaidi (2012), and Ramos (2016), it is crucial for learners to receive ongoing support from teachers. This support includes providing students with the necessary skills and techniques to develop their ability to learn independently. The focus should be on teaching students how to learn, rather than what to learn, as emphasized by Hamilton (2013). Some interviewees’ ideas might correspond to this notion of interdependent learning. Participant #35 described LA as a process where “students take control and responsibility for their own learning, both in terms of what they learn and how they learn it.” He emphasized the importance of self-direction, while also acknowledging that teachers play a vital role by providing support through scaffolding tasks in online classes. Similarly, Participant #17 explained that LA involves learners assuming full responsibility for their own learning; however, she stressed the collaborative aspect, as learners are aided by peers in group tasks. In contrast to Participant #35, who focused on teacher support through scaffolding, she highlighted the role of tools like Padlet or Mentimeter, which allow teachers to reflect on student outcomes in virtual classrooms. Furthermore, Participant #27 underscored the importance of real-life examples in lesson plans, suggesting that practical application increases student engagement. Unlike the other participants, she also proposed that students maintain personal blogs or journals to reflect on their learning, thereby helping teachers identify both strengths and areas for improvement.

The recognition of interdependent learning in COL reflects the emphasis on social autonomy (Holliday, 2003), where students’ interactions can foster a sense of collective agency as they support and assist each other to ensure the quality and accuracy of their work (Pellerin, 2017). The results from question 17 of the online survey indicate varied practices among teachers regarding the design of teamwork or groupwork tasks in online lessons. Almost half of the respondents, around 49%, reported that they sometimes incorporate teamwork or groupwork in their lessons. Meanwhile, about 40% of participants stated that they always include such tasks in every online session. On the other hand, a smaller percentage, approximately 11%, indicated that they rarely design groupwork tasks, and no respondents reported never using them. Evidently, the transition from theory to practice poses a challenge for teachers in fostering the self-directed and cooperative abilities of students in online classrooms. The reasons for this can be elucidated by the various impediments as exemplified in the subsequent section.

Factors Prevent the Implementation of LA in COL

In relation to question 27, most participants (68.09%) agreed with the assertion made by Cappellini et al. (2017) that autonomy is contingent upon the specific circumstances. Borg & Al-Busaidi (2011) classify the challenges in promoting LA within the teaching context into three primary categories: (1) teacher factors, (2) institutional factors, and (3) learner factors.

Table 4

Results from Question 27 of the Survey

In comparison with the interviews, it could be said that the participants were fully aware of the fact that the teaching context may restrict their teaching practice. For instance, participant #25 pointed out that the “teacher’s ability to use technology in online learning” is a significant issue in promoting LA within COL. She noted that not all teachers are proficient in “operating computers or gadgets” for online learning activities. Additionally, teachers face limitations in maintaining control during online sessions, particularly due to the “absence of a discussion forum” feature in the applications they use. Conversely, participant #35 emphasized the challenges faced by students, particularly their lack of access to “digital devices such as computers, laptops, tablets, or smartphones,” which leads to insufficient digital literacy. He also highlighted that “Internet connection is not good enough” for some students, and in certain areas, students “don’t have Internet access” at all. Moreover, he stressed that the learning experience in online environments is entirely different, with many students preferring the “real classroom atmosphere” instead of merely sitting in front of computers and performing tasks digitally. This comparison between teacher and student challenges reflects the broader difficulties in adapting to online learning.

It becomes apparent that approximately half of the participants infrequently incorporated teamwork or groupwork into their virtual classes. The majority of participants, 95%, acknowledged that the primary obstacles to fostering autonomous capacity in COL are the allocation of time to develop lesson plans and the execution of collaborative tasks in virtual classes. The results from question 29 of the online survey reveal that most respondents believe online learning places additional demands on ELT teachers in terms of lesson preparation. More than 60% of participants strongly agreed, while around 30% mostly agreed with this statement. A small percentage remained neutral, indicating that they neither agreed nor disagreed. Similarly, question 32 highlights the challenges associated with implementing collaborative learning in online environments. Approximately 40% of respondents strongly agreed that it is difficult to effectively carry out collaborative learning in online classes, and nearly 35% mostly agreed. Around 15% of participants neither agreed nor disagreed, while a smaller proportion expressed disagreement, indicating varying perspectives on the feasibility of collaborative learning in virtual classrooms.

This outcome brought focus to a troublesome aspect of the COL, highlighting the challenges teachers face in effectively implementing this approach. The difficulty lies in coordinating group activities, ensuring active participation from all students, and managing diverse learning paces. The triangulation with the interviews reflected the same pattern. Participant #2 explained that the “curriculum is always set by the university” and teachers must “follow the syllabus strictly.” This constraint, even in traditional classrooms, makes it challenging to design collaborative tasks, particularly when the “volume of knowledge is very large” in a single lecture. Furthermore, when transitioning to online classes, these challenges intensify as teachers require “more time to deliver the lesson,” making the organization of such activities nearly impossible. Moreover, participant #23 emphasized the practical challenges of virtual environments, stating that it is “very difficult to give feedback or observe different teams at the same time” when they are working in breakout rooms on virtual learning platforms. Similarly, participant #9 highlighted another layer of difficulty in maintaining control, especially when “students do not like taking part in group work or pair work,” which further complicates the effective implementation of collaborative learning in both traditional and online settings. This observation aligns with previous research (Benson, 2007; Benson & Huang, 2008) where scholars proposed that the transfer of autonomy to classroom settings should prioritize the independence of teachers. The concept of autonomy implies a willingness to foster opportunities for teachers’ professional freedom within the workplace.

Discussion

The findings of this investigation provide a glimpse into the perspectives and perceptions of ELT lecturers with respect to LA and COL. Although a substantial majority of the participants acknowledged the importance of autonomy in ELT, the varying levels of comprehension among them suggest a multidimensional perspective on the concept. It is aligned with prior research that perceptions of autonomy are frequently influenced by individual experiences and educational backgrounds (Elliott, 2016). While most teachers comprehended LA, some exhibited a limited understanding. This highlights the need for improved professional development in this field and reveals a discrepancy between the theoretical understanding of autonomy and its practical application in the classroom.

The participants displayed varying degrees of understanding regarding collaborative learning, as certain individuals struggled to articulate a thorough explanation. This differentiation indicates that not all teachers possess a comprehensive understanding of the distinction between cooperative and collaborative learning, which is consistent with the research conducted by Demosthenous et al. (2020). Some participants associated collaborative learning with the division of tasks or working in groups, which implies a more cooperative mindset than a genuine collaborative one in which learners actively engage to generate knowledge. These results emphasize the urgent necessity for a more sophisticated comprehension of COL and its potential pedagogical applications.

Most teachers concurred that their beliefs and teaching methods play a vital role in nurturing autonomy among students aligning with the idea that TA and LA are interconnected. Nevertheless, a small portion of participants supported a perspective on autonomy, which emphasizes the freedom to make decisions (Borg & Al-Busaidi, 2011). This restricted support for the autonomy aspect may indicate that they are feeling constricted by institutional curricula and policies that impede their ability to promote autonomy in their teaching practices. Within contexts of higher education in Vietnam, it aligns with the outcomes of the interviews, which indicated that participants encountered challenges in changing from conventional and teacher-centered methodologies.

In COL, it is essential to emphasize the significance of teachers in fostering autonomy among learners. While they generally recognized the significance of aiding students in becoming self-sufficient, they faced practical obstacles when it came to implementing collaborative activities in virtual classrooms. The results of this study are consistent with the previous research conducted by Benson and Huang (2008), which underscores the importance of instructor training and support in fostering student independence. Even though most teachers recognize the importance of LA and collaboration in the learning process, there are still significant challenges to implementing these concepts in both in-person and online environments. It is suggested that teachers need additional training to ensure that their understanding of autonomy is in accordance with its practical application in collaborative learning scenarios.

Conclusion

This study investigated the level of comprehension among English teachers at a Vietnamese university regarding the concept of LA and TA, within the context of COL as it relates to their teaching methods. The results were in line with previous studies in the aspect that contextual factors have a significant impact on teacher beliefs regarding language learning and teaching (Orsini-Jones, 2015; Orsini-Jones et al., 2017; Phi, 2019). However, the findings revealed that some teachers are encountering various obstacles that could hinder the integration of autonomous capability in COL to a certain degree.

The findings demonstrated that the lecturers had different understandings of LA and TA, considering their political, technical, and psychological aspects (Benson, 1997), as well as the social perspective of autonomy (Holliday, 2003). Many lecturers possess the ability to understand the language used in collaborative learning. The cultural background of language learning and teaching can exert a significant influence on the beliefs of teachers (Klapper, 2006). The participants regarded autonomy COL as encompassing both interdependent learning and independent learning processes (Littlewood, 1999). Receiving support from both language teachers and peers is crucial for learners to enhance the process of becoming more autonomous. However, some teachers still struggle with understanding and implementing autonomy and collaborative learning in their classrooms.

For certain teachers who are not proficient in digital technology, the issue of autonomy continues to be a challenge. The study identified several technical factors that can impede the implementation of collaborative tasks in virtual classrooms, which are intended to promote learner autonomy. These factors encompass the sum of the time teachers allocate for lesson planning, student motivation, and the level of student participation. An inherent constraint of this study was the limited number of participants engaged. The findings presented herein pertain solely to a limited-scale investigation involving 47 ELT teachers, and only a subset of the participants was able to partake in the interview.

The study identified that some teachers encounter difficulties in utilizing technology effectively. Consequently, additional research should investigate the influence of digital literacy on the promotion of student autonomy in online environments and the examination of student perspectives on autonomy in COL environments to enhance comprehension of their motivation, engagement, and perceptions of autonomy in a virtual environment. Further research is required to investigate the long-term effects of autonomy in online learning on the students’ academic performance and personal development, as well as to investigate the methods by which institutional guidelines and systems support student autonomy in virtual classrooms that are characterized by technical and logistical challenges.

Notes on the Contributor

Tran Thi My Linh, a PhD candidate, is a lecturer at English Practice Department, Faculty of English, Thuongmai University in Vietnam. She received a bachelor’s degree in English Language Teaching from Hanoi National University of Education and a master’s degree from the University of Languages and International Studies. She is currently a PhD student at National Dong Hwa University, Taiwan. She has been teaching EFL courses for over 9 years. Her research interest includes English Language and English Teaching Methodology.

References

Benson, P. (1997). The philosophy and politics of learner autonomy. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 18–34). Routledge.

Benson, P. (2000). Autonomy as a learners’ and teachers’ right. In Learner autonomy, teacher autonomy: Future directions (pp. 111–117). Longman.

Benson, P. (2001). Autonomy in language learning. Longman.

Benson, P. (2007). Autonomy in language teaching and learning. Language Teaching, 40(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444806003958

Benson, P. (2013). Teaching and researching: Autonomy in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833767

Benson, P., & Huang, J. (2008). Autonomy in the transition from foreign language learning to foreign language teaching. DELTA: Documentação de Estudos em Lingüística Teórica e Aplicada, 24, 421–439. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-44502008000300003

Borg, M. (2001). Key concepts in ELT teachers’ beliefs. ELT Journal, 55(2), 186–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/eltj/55.2.186

Borg, S. (2003). Teacher cognition in language teaching: A review of research on what language teachers think, know, believe, and do. Language Teaching, 36(2), 81–109. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0261444803001903

Borg, S., & Al-Busaidi, S. (2011). Teachers’ beliefs and practices regarding learner autonomy. ELT Journal, 66(3), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccr065

Borg, S., & Al-Busaidi, S. (2012). Learner autonomy: English language teachers’ beliefs and practices. ELT research paper 12-07. The British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/b459%20ELTRP%20Report%20Busaidi_final.pdf

Cappellini, M., Lewis, T., & Rivens Mompean, A. (2017). Learner autonomy and web 2.0. Equinox.

Ciekanski, M. (2007). Fostering learner autonomy: Power and reciprocity in the relationship between language learner and language learning adviser. Cambridge Journal of Education, 37(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640601179442

Demosthenous, G., Panaoura, A., & Eteokleous, N. (2020). The use of collaborative assignment in online learning environments: The case of higher education. International Journal of Technology in Education and Science, 4(2), 108–117. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijtes.v4i2.43

Dickinson, L. (1987). Self-instruction in language learning. Cambridge University Press.

Donaghue, H. (2003). An instrument to elicit teachers’ beliefs and assumptions. ELT Journal, 57(4), 344–351. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/57.4.344

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Teaching and researching motivation. Longman.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford University Press.

Elliott, D. (2016). Autonomy and foreign language learning in a virtual learning environment. ELT Journal, 70(2), 235–236. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccw002

Ellis, R., & Shintani, N. (2014). Exploring language pedagogy through second language acquisition research. Routledge.

Geng, J. (2010). Autonomy for English teaching and learning in China. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 1(6), 942–944. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.1.6.942-944

Hamilton, M. (2013). Autonomy and foreign language learning in a virtual learning environment. Bloomsbury.

Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy and foreign language learning. Pergamon.

Holliday, A. (2003). Social autonomy: Addressing the dangers of culturism in TESOL. In D. Palfreyman & R. C. Smith (Eds.), Learner autonomy across cultures: Language education perspectives (pp. 110–126). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230504684_7

Holmes, A. G. (2021). Can we actually assess learner autonomy? The problematic nature of assessing student autonomy. Education, 9(3), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.34293/education.v9i3.3858

Illes, E. (2012). Learner autonomy revisited. ELT Journal, 66(4), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccs044

Ishak, M. Z., Han, C. G. K., Ngui, W., Keong, T. C., & Satu, H. U. (2023). Teachers’ beliefs of coronavirus on online learning. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), 8(7), e002410-e002410. https://doi.org/10.47405/mjssh.v8i7.2410

Klapper, J. (2006). Understanding and developing good practice: Language teaching in higher education. CILT, the National Centre for Languages.

Little, D. (1991). Learner autonomy 1: Definitions, issues and problems. Authentik

Little, D. (1994). Autonomy in language learning: Some theoretical and practical considerations. In A. Swarbrick (Ed.), Teaching modern languages (pp. 81–87). Routledge.

Little, D. (1995). Learning as dialogue: The dependence of learner autonomy on teacher autonomy. System, 23, 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/0346-251x(95)00006-6

Little, D. (1996). Freedom to learn and compulsion to interact: Promoting learner autonomy through the use of information systems and information technologies. In R. Pemberton, S. L. Edward Li, W. F. Winnie, & H. D. Pierson (Eds.), Taking control: Autonomy in language learning (pp. 203–218). Hong Kong University Press.

Little, D. (2001). Learner autonomy and the challenge of tandem language learning via the Internet. In A. Chambers & G. Davies (Eds.), ICT and language learning: A European perspective (pp. 29–38). Swets & Zeitlinger.

Little, D. (2007). Introduction: Reconstructing learner and teacher autonomy in language education. In A. Barfield & S. H. Brown (Eds.), Reconstructing autonomy in language education inquiry and innovation (pp. 1–12). Palgrave MacMillan.

Little, D. (2016). Learner autonomy and second/foreign language learning. Retrieved from https://www.llas.ac.uk//resources/gpg/1409

Littlemore, J. (2001). Learner autonomy, self-instruction and new technologies in language. In A. Chambers & G. Davies (Eds.), ICT and language learning: A European perspective, 1, (pp. 39–52). Swets & Zeitlinger.

Littlewood, W. (1999). Defining and developing autonomy in East Asian contexts. Applied linguistics, 20, 71–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/20.1.71

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M. (2005). Second language research: Methodology and design. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Nambiar, D. (2020). The impact of online learning during COVID-19: students’ and teachers’ perspective. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 8(2), 783–793.

Orsini-Jones, M. (2015, November, 5). Integrating a MOOC into the MA in English language teaching at Coventry University: Innovation in blended learning practice. AdvanceHE https://advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/integrating-mooc-ma-english-language-teaching-coventry-university-innovation-blended

Orsini-Jones, M., Conde Gafaro, B., & Altamimi, S. (2017). Integrating a MOOC into the postgraduate ELT curriculum: Reflecting on students’ beliefs with a MOOC blend. In In Q. Kan & S. Bax (Eds), Beyond the language classroom: researching MOOCs and other innovations, (pp. 71–83). Research-publishing.net. https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2017.mooc2016.672

Pellerin, M. (2017). Rethinking the concept of learner autonomy within the MALL environment. In M. Cappellini, T. Lewis, & A. R. Mompean (Eds.), Learner autonomy and Web 2.0 (pp. 91–114). Equinox Publishing.

Pennington, M. C. (1996). When input becomes intake: Tracing the course of teachers’ attitude change. In D. Freeman & J. C. Richards (Eds.), Teacher learning in language teaching (pp. 320–348). Cambridge University Press.

Phi, M. T. (2019). Becoming autonomous learners to become autonomous teachers: Investigation on a MOOC blend. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching 7(4)15–32. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJCALLT.2017100102

Phipps, S., & Borg, S. (2009). Exploring tensions between teachers’ grammar teaching beliefs and practices. System, 37(3), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2009.03.002

Polkinghorne, D. E. (2005). Language and meaning: Data collection in qualitative research. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 52(2), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.137

Ramos, R. C. (2016). Considerations on the role of teacher autonomy. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 183–202. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.10510

Reinders, H., & Hubbard, P. (2013). CALL and learner autonomy: Affordances and constraints. In M. Thomas, H. Reinders, & M. Warschauer (Eds.), Contemporary computer-assisted language learning (pp. 359–375). Continuum Books.

Reinders, H., & White, C. (2016). 20 years of autonomy and technology: How far have we come and where to next? Language Learning & Technology, 20, 143–154. http://dx.doi.org/10125/44466

Richards, J. C., & Lockhart, C. (1994). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. Cambridge University Press.

Silverman, D. (2014). Interpreting qualitative data. Sage

Sinclair, B. (2000). Learner autonomy: The next phase. In B. Sinclair, I. McGrath, & T. Lamb (Eds,), Learner autonomy, teacher autonomy: Future directions (pp. 4–14). Longman.

Smith, R. (2000). Starting with ourselves: Teacher-learner autonomy in language learning. In B. Sinclair, I. McGrath, & T. Lamb (Eds.), Learner autonomy, teacher autonomy: New directions (pp. 89–99). Longman.

Vidosavljević, M. (2023). Foreign language teaching in a digital environment: Teachers’ attitudes and beliefs. PHILOLOGIST – Journal of Language, Literature, and Cultural Studies, 14(27), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.21618/fil2327153v .

Yuzulia, I. (2020). EFL teachers’ perceptions and strategies in implementing learner autonomy. Linguists: Journal of Linguistics and Language Teaching, 6(1), 36–54. http://dx.doi.org/10.29300/ling.v6i1.2744

Zhang, C. (2020). From face-to-face to screen-to-screen: CFL teachers’ beliefs about digital teaching competence during the pandemic. International Journal of Chinese Language Teaching, 1(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.46451/ijclt.2020.06.03