Cemil Gökhan Karacan, English Language & Literature, Beykent University, Turkey. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9663-5021

Melike Bekereci-Şahin, Department of Foreign Language Education, Middle East Technical University, Turkey. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3803-4399

Karacan, C. G., & Bekereci-Şahin, M. (2025). Exploring a collaborative synchronous online learning environment in an initial language teacher education program. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(3), 477–503. https://doi.org/10.37237/202404

First published November 13, 2024

The qualitative study explores pre-service language teachers’ experiences in a collaborative synchronous online course in language teacher education program in Turkey. A course was designed to equip pre-service language teachers of English with the skills and knowledge necessary to effectively incorporate technology into their teaching and self-learning practices. Adopting a generic qualitative inquiry design, data were collected over 14 weeks from 63 pre-service EFL teachers through weekly reflection papers, online surveys, and face-to-face follow-up semi-structured interviews. The study found that technology-enhanced collaborative online course had a positive influence on participants’ engagement, interaction, and professional development with participants perceiving the course experience positively. The findings suggest that collaborative online courses, when they are effectively taught, can be a valuable professional development opportunity in initial language teacher education programs.

Keywords: collaborative synchronous online course, online learning environments, virtual learning environments, professional development

In our day-to-day teaching, learning management systems (LMS), Web 2.0 tools, data analytics, video conferencing platforms and virtual learning environments (VLE) are integrated into everyday teaching practices. While some scholars define learning environments (LE) as the place where the course content and homework submissions are stored, shared, and worked on, others define it as the holistic place where, in addition to those mentioned before, students and teachers gather and interact; and sometimes even extend the learning process beyond the classroom. At a tertiary level, the LE is not limited to the four walls of a classroom, and university lecturers strive for other instructional techniques that can contribute to their students’ varying skills. In teacher education programs, pre-service teachers need a wide array of skills that cannot be easily acquired during class hours.

In this study, we present a technology-supported virtual learning environment, enriched with collaborative teaching and out-of-class learning opportunities, within an initial language teacher education program at a foundation university. The study aims to explore the experiences of pre-service English teachers as they engage with this virtual learning environment.

Virtual Learning Environments

Learning environments are social contexts in which students interact with their peers and teachers (Graetz, 2006). A learning environment is one that is learner-centered, realistic, and effective (ElSayad, 2023; Herrington & Herrington, 2006). It is also one where students can communicate their ideas (Kaufmann & Vallade, 2022) and one that is responsive to students’ needs (Sande & Burnett, 2023). A learning environment should meet the needs of learners as it is a place where students can communicate their ideas and where they are motivated to learn (Sande & Burnett, 2023).

It is vital to offer self-regulation practice opportunities to pre-service teachers (Yılmaz-Na & Sönmez, 2023). Providing relevant learning experiences where pre-service teachers can practice taking charge of their own learning while they learn how to plan, monitor, and reflect on their own learning is one effective strategy for developing self-regulation abilities (Randi, 2004). If the learning environment requires knowledge production, they will also more actively engage in the course content.

In initial teacher education programs, provided that they are effectively employed by teacher education professors, VLEs provide a flexible and convenient way to access educational content and resources, and this allows pre-service teachers to learn at their own pace and from any location (Debbag & Fidan, 2022). Professors’ VLE-related practices may also influence pre-service teachers who are likely to implement those in their future classrooms. These environments can give pre-service teachers the opportunity to collaborate and communicate with other students and teachers, which can support the development of their social and emotional skills and enhance their learning experience (Özüdoğru, 2021). By offering pre-service teachers tailored learning paths and recommendations based on their unique needs and preferences, VLEs can also facilitate personalized and adaptive learning (Syah et al., 2020). By providing personalized and adaptive learning paths, learning outcomes can be enhanced and pre-service teachers can be better prepared for the demands and obstacles that the teaching profession may present.

Furthermore, according to Can and Simsek (2015), VLEs can assist pre-service teachers in gaining the skills and knowledge necessary to use technology in the classroom. Pre-service teachers who are familiar with VLEs and other digital tools will be more equipped to incorporate technology into their teaching practices and to assist their students’ learning as the use of technology in education continues to expand (Nissim et al., 2016).

Interaction

Interaction plays a crucial role in the effectiveness of VLEs. Interaction in a VLE refers to the instructional materials and resources, as well as the ways in which teachers and students interact and communicate with one another. This may reflect itself in discussion forums, online quizzes and assessments, group projects, and real-time video conferencing. The role interaction plays in a VLE is to facilitate engagement and collaboration among students and teachers, and to provide opportunities for students to apply and demonstrate their knowledge and skills (Ak & Gökdaş, 2021). By providing a platform for interaction, these environments can help to create a more dynamic and engaging learning experience for improved learning outcomes (Borba et al., 2018). Moreover, interaction can help to build a sense of community and connection among students and teachers, which can support social and emotional learning and contribute to creating a more supportive and inclusive LE (Borba et al., 2018; Chao et al., 2024).

Students’ Perceptions of the Learning Environments

The perceptions of students towards VLEs are particularly important as perceptions towards an environment could affect the learning process. Understandably, this can depend on several factors, such as the student’s individual learning style, their previous experiences with virtual learning (Bozkurt & Sharma, 2020), and the specific VLE they are using (Hrastinski, 2008). Student perceptions of VLEs vary; some find them convenient and flexible for accessing content (Bozkurt & Sharma, 2020), while others perceive them as impersonal, and lacking collaboration. Additionally, while some students appreciate the positive and engaging aspects of such environments (Artino & Stephens, 2009), others may face challenges with the lack or absence of face-to-face interaction, and the requirements for self-motivation, self-regulation and discipline (Huang et al., 2020). VLEs are not places where only learning occurs, they have an influence on students’ thinking processes, behaviors and feelings (Graetz, 2006). For instance, when a LE is supportive and centered on the needs of the students, it allows the students to engage in constructive learning experience (Ni et al., 2010).

In general, students’ perceptions of VLEs are likely to be influenced by the quality and effectiveness of the VLE, as well as by the student’s personal preferences and experiences (Jaggars, 2014).

Deep Learning

VLEs provide learners with the range of content and material available to make learning permanent (Mimirinis & Bhattacharya, 2007). The ‘deep learning’ concept, also referred to as ‘cognitive active learning,’ is the actual understanding of the subject matter (Jiang, 2022). Students who engage in cognitive active learning modify their knowledge by going beyond the basic understanding. Deep learners, as opposed to surface learners, strive to achieve a deeper comprehension of the subject matter. Since VLEs demand self-directed learning skills, they create more opportunities for students to engage in deep learning. Deep-learning practitioners connect with the content by developing meaningful discussions and using practical examples from their daily lives. As a result, instead of rote memorization, students critically interact with the content and maintain it in their long-term memory (Baker et al., 2010; Ke & Xie, 2009).

Framework

The impact of students’ perceptions of a learning environment can be easily framed within the 3P model suggested by Biggs (1999), which conceptualize the learning process as an interacting system with of three sets of variables: the learning environment and student characteristics (presage), students’ approach to learning (process), and learning outcomes (product).

In principle, the model suggests that personal and situational variables impact a student’s learning strategy, which in turn mediates or influences the types of outcomes attained; and second, that presage elements (e.g., perceptions of the learning environment) can also significantly affect instructional objectives.

Presage factors are those that exist prior to the time of learning, as the term implies, and are divided into two categories: long-standing personal characteristics brought to the learning situation by the student (e.g., prior knowledge, academic ability, personality) and situational characteristics that characterize the learning environment such as teaching methods, workload, course structure (Biggs, 1999). Biggs (1999) emphasizes that the way students perceive their learning environment, which is shaped by their motivations and expectations, plays a crucial role in how situational factors impact their learning methods and results.

Process factors outline the way students approach their learning. Despite the ongoing discussions about these approaches, two essential orientations or approaches emerged. Deep learning involves seeking for increased comprehension through the application and comparison of ideas. In contrast, surface learning comprises reproductive strategies without a solid integration of information (Marton & Säljö, 1976; Thomas & Bain, 1984).

The product is the result of learning outcomes (cognitive, emotive, or behavioral) that students develop during the learning process (Biggs, 1999). Affective learning outcomes, on the other hand, include course satisfaction and perceptions of skill development (Aworuwa & Owen, 2009). The model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

A General Model of Student Learning Process (adapted from Biggs, 1999)

Considering all of this, schools now have a duty to provide learning environments that not only increase the likelihood of student success but also give students the opportunity to become more involved (Deci et al., 1991; Pai et al., 2014). The impact of the learning environment on student learning and other beneficial effects is documented in the relevant literature, but it also offers a chance for active learning and student involvement (Deci et al., 1991). Thus, the research question specified below drives the current study:

How do pre-service EFL teachers experience a collaborative synchronous online course enhanced with in- and out-of-class learning opportunities?

Methodology

A generic qualitative approach has been chosen for the current study since it allows researchers to draw conclusions from subjective opinions of participants in their own settings without the limitations of a specific qualitative approach (Caelli et al., 2003). To this end, it offers an opportunity to investigate and describe the experiences of instructors and pre-service English language teachers in an online synchronous learning environment at a tertiary level.

Setting and Research Context

The current study was conducted in an English Language Teacher Education program of a foundation university located in Istanbul, Turkey, a city that serves as the country’s cultural and economic hub and is uniquely situated on the European continent. In the context of the study, the technological infrastructure and device ownership are in a desirable state, indicating that our students come from backgrounds that are relatively familiar with technology. The course offered was fully online, supported with out-of-class online activities. The course was conducted with two lecturers who were also the researchers of the current study. Lecturer-1 is a tech-savvy teacher educator with versatile experience giving Instructional Technologies courses, while Lecturer-2 is a teacher educator with considerable field knowledge, teacher education expertise and qualitative research experience. Lecturer-1 took the role of lecturing and presenting course content while Lecturer-2 was directing the questions and guiding the discussions as a mediator.

Participants

There were 69 pre-service English language teachers in the second year of the teacher education program; however, six of them were excluded from the study because of the following reasons: four of them did not complete the required weekly tasks and two of them did not attend the sessions regularly. To this end, 63 pre-service English language teachers were selected as the participants of this study. The average age was 20, and the gender distribution was 18 Males and 45 Females.

In order to ensure the protection of participants’ personal data, the researchers distributed informed consent forms to participants to get their permission and provide necessary information about the study. Also, numbers were given to each participant to ensure anonymity.

Data Collection Tools

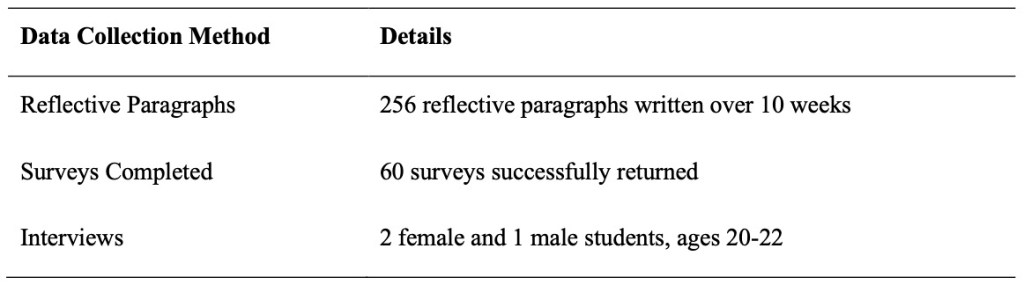

In generic qualitative inquiry, semi-structured interviews, reflective practices, and open-ended surveys are some of the most widely used and valid means of data collection (Percy et al., 2015). In this study, the relevant data was collected through weekly reflection papers, an online open-ended survey, and face-to-face follow-up semi-structured interviews. The data collection process began with the first part of an open-ended survey aimed to determine participants’ base level of teacher digital competence.

It continued with collecting pre-service teachers’ weekly reflection papers in order to have a first insight into their perceptions and experiences related to the course. Reflection papers were written by the participants as their weekly assignments for the course. Each week, the participants composed reflections to share their perceptions about the usage of the application or the practicality of the digital platform they learnt. They were also encouraged to share their experiences related to the learning environment.

At the end of the implementation, participants were given the second part of the survey providing detailed responses on the topics in their reflection papers. They answered five open-ended questions designed for the evaluation of the learning environment in their own words. Finally, face-to-face semi-structured follow-up interviews were conducted with three volunteer participants to gain deeper insights into the suggestions made in the survey.

An invitation email was sent to all participants with the necessary information about the interview procedure, and after waiting for a week, three participants accepted the invitation. They were asked questions related to evaluating the learning environment with specific experiences they had, describing their engagement to the course, and their suggestions for the development of the course. Each interview lasted for approximately fifteen minutes. The data collection procedure is demonstrated in Table 1.

Table 1

Summary of Data Collection Methods

Data Analysis

Firstly, with the aim of profiling the digital savviness and competence of the participants, descriptive data were collected through an online survey and analyzed using statistical analysis software. After that, as for our primary data, data analysis steps suggested by Persson (2006) were followed. VSAIEEDC model of data analysis is used in generic qualitative research since it is a cognition-based, rigor and reflexive model (Chi Vo et al., 2012). Offering a prescriptive approach to generic data analysis, the VSAIEEDC model consists of the following seven steps: variation, specification, abstraction, internal verification, external verification, demonstration, and conclusion (Kennedy, 2016). While analyzing the collected data for the current study, the researchers first scanned the raw data to get immediate perceptions of recurring patterns. After that, the variation and similarities among recurring patterns were identified. As a third step, commonalities were extracted and coded. Before starting categorization of codes, internal verification was employed to check if the codes were logical and feasible. In this step, we also endeavored to eliminate the researchers’ personal bias. Right after, codes were grouped into categories. In qualitative studies, researchers need to construct trustworthiness of their study (Creswell, 2009). In order to achieve this aim, external verification was employed by means of data triangulation and member-checking which are valid strategies for verification (Morse et al., 2002). The demonstration step was achieved by visualizing data in a charted form. Finally, the conclusion step within the model was accomplished after data saturation, where no new categories could be extracted from data analysis. The whole process was conducted three times for the data collected by means of three data collection tools namely reflection papers, online survey, and face-to-face follow-up interviews. After implementing the VSAIEEDC model three times and identifying themes, these were grouped again to reach overarching themes and report on them. In this step, overarching themes were supported with vignettes of participants since the participants gave the researchers examples from their own practices.

Findings

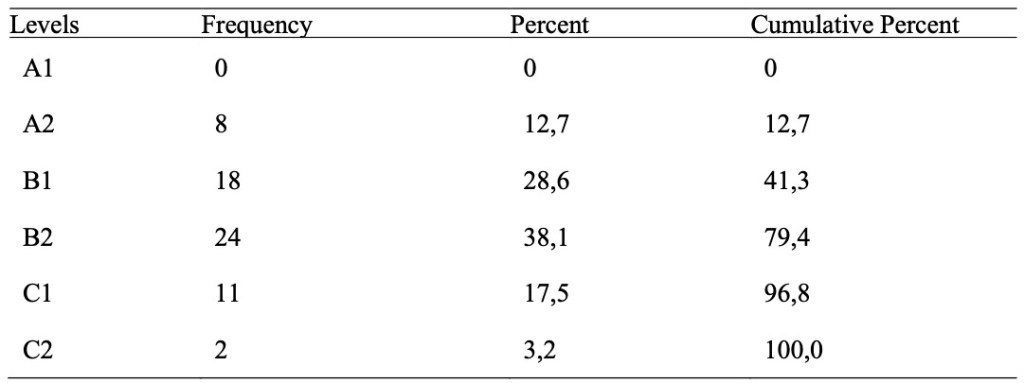

Descriptive statistics were run to investigate the participants’ perceived digital competence. Most participants claim to have a teacher digital competence level between B1-C1. Not a single individual reported having a digital competence level of A1 (Table 2).

Table 2

Participants’ Self-Reported Teacher Digital Competence Levels

Other statements on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 were also present in the survey; for example, their perceived digital competence (M=2,70) and finding it easy to work with computers and other technical equipment (M=4.25). They use the internet extensively and competently (M=4.22) and, furthermore, they are open and curious about new digital means (M=4.41). Relatively lower than the other measures, participants’ social network engagement had a mean score of 3.83 (Table 3).

Table 3

Participants’ Digital Savviness and Utilization

Having presented descriptive statistics regarding the participants’ digital savviness and utilization, the following section shows the students’ perceptions about the learning environment and their suggestions to establish a positive and learner-friendly course atmosphere. The data analysis of weekly reflection papers, online open-ended surveys, and face-to-face follow-up semi-structured interviews led us to create five overarching themes: course experience, student engagement, professional development, quality of interaction, and student teachers’ expectations.

Course Experience

Course experience refers to any contact with people and events in which learning takes place. Within this theme, three sub-themes were found thanks to the thematic analysis: satisfaction with course content, instructor attitudes, and teaching organization.

The students expressed their satisfaction with the learning environment since they experienced the relevance between course aim and course content. They also mentioned that the course was designed to show students how non-educational technological platforms could be used for teaching purposes. Two of the students stated that the course met their expectations:

This course gave me the competence of accessing information more easily, producing content, and presenting new things about ELT on my social media (P2, Survey).

I have always wanted to open my own blog; however, I did not know how to do it. Thanks to this course, I had a chance to create my own blog to share my ideas about teaching and the information I found while doing research on innovations in ELT. I have gained new ideas, experiences, and information (P3, Reflection paper).

While some of the students implied that they felt the lack of technological competence as teacher candidates, the rest (of them) mentioned their competence in technology, as well as their satisfaction with learning new methods to integrate technology with teaching language thanks to this course. One of the participants highlighted the importance of the course with the following excerpt: “I am good at technology, but I have never realized that I definitely needed this course until I took it this semester” (P10, Reflection paper). Likewise, one of the students remarked:

Before taking this course, I used applications, social media, or digital platforms just for entertainment. I also knew a lot about virtual and augmented reality. Now, I can use them more comprehensively for my learning and teaching. Technology is no longer just for surfing the internet, watching movies, or playing games for me (P28, Reflection paper).

Establishing a good relationship with instructors resulted in an engaging, student-centered, and responsive learning environment. All participants mentioned that instructor attitudes and behaviors played a critical role in their motivation and success in the course. They also indicated that the course atmosphere was encouraging and pleasant, especially for students who had fears about taking a course related to technology. They shared their feelings with the following words:

In this course, we never felt overwhelmed and stressed because our instructors were very approachable. We could easily see that they enjoyed the course. Their positive attitudes increased learning opportunities and increased our awareness (P12, Survey).

I had serious concerns about this course because I was not interested in technology. I thought that it was impossible for me to pass this course. However, thanks to our instructors’ kindness and patience, I started to be interested in using technology and the course turned into a meeting with them rather than a compulsory session for me. I feel more confident, and my digital competence has evolved after taking this course from my instructors (P7, Survey).

Addressing the interests of students in addition to their needs boosted the efficiency of the course. Two of the students stated:

Our instructors know the things that we are interested in, and it was a motivation for us. We could talk about Minecraft, Roblox, and so on. The way they taught the course was enjoyable and informative at the same time (P32, Survey).

It was good to have instructors who were familiar with our interests. They designed the course by considering our world, so we came to class motivated and excited to learn (P3, Survey).

In addition to feeling comfortable and confident in the class, most of the participants mentioned the key role of course design in their engagement with the course as well. Students emphasized that the instructors’ effort devoted to teaching and advising contributed to a positive course atmosphere and success in learning. Students remarked that the course syllabus was successful in terms of enhancing participation and interest in the course. Two students wrote about the constructive teaching organization as follows:

To be honest, I did not have much interest in technology before I took this course; however, when I saw our instructors’ effort while delivering this informative and entertaining course, I completely changed my perspective (P42, Reflection paper).

I benefit from the digital resources they [instructors] are sharing in the class. Also, we talk about how to use them to teach English. We discuss their efficiency in terms of teaching, and we gain critical thinking skills (P57, Reflection paper).

Student Engagement

The second overarching theme was student engagement. In education, student engagement refers to the curiosity and passion that they have during the course, which maximizes achievement and learning outcomes. At the end of the thematic analysis, the following three sub-themes were found: high degree of attention, deep learning opportunities, and instructors’ facilitation of learning environments.

For the sub-theme high degree of attention, students reflected their engagement with the learning environment by mentioning their willingness to listen attentively and participate in class discussions. Also, they highlighted their curiosity towards certain topics. One of the students spoke about how she appreciated the learning environment:

I was very open in expressing myself because the environment was very friendly. Because of this, we never stopped being attached to the course flow. Personally, I was always looking forward to seeing the next topic planned by our instructors. I experienced boredom and being disaffected many times before. So, I can make a comparison. I am sure the rest of the class feels the same way (P12, Survey).

Many students commented that creating inspiration was the key element for making the learning environments engaging and contributive. According to them, inspiration led to an inquisitive and passionate learning atmosphere. One student stated, “we learnt topics that we may encounter in our daily lives; that’s why we enjoyed and were curious about the course. For example, I continued searching the topics we covered last week after the session” (P58, Reflection paper).

The deep learning opportunities subtheme referred to learning activities through experience and reflection. Most of the students remarked that they could practice the course content via meaningful assignments. The students also noted that reflecting upon what they have already used in their daily lives could help them internalize the course content, for example:

I was familiar with the technology that our instructors offered but I did not think about them before. Previously, I was trying to learn a new app or website but since I did not use them in-depth, I forgot them gradually. I think not just using, but also writing or taking notes about them helped us fully comprehend the topics (P16, Survey).

Another sub-theme that has emerged is the instructors’ facilitative role to scaffold student engagement. Firstly, it was mentioned that student engagement in a course or subject highly depends on the students’ efforts and should be supported by a positive classroom atmosphere. The participant, who wrote in the survey that she felt highly interested in the course thanks to the positive classroom atmosphere, mentioned during the interview the role of student in engagement to the course:

Your PC is ready for you, your instructors are there to help you. If you still say that you do not benefit from this course, it is not realistic. For example, whenever our instructors mentioned an application, I immediately googled it to check its website and I tried to download it to check over later. (P12, Interview).

According to the participants, instructors’ facilitative behaviors also take part in student engagement. Two participants expressed themselves as follows:

We always felt our instructors’ support and we were always sure about their competence. They facilitate us because of their self-confidence. Once you feel the incompetence of your instructor, it is impossible to be motivated (P6, Interview).

I was engaged in this course thanks to the activities our instructors chose for us. I will benefit from them in the future. Applications and blog writing assignments were beneficial (P4, Interview).

Professional Development

Professional development is the third overarching theme, and this theme broadly refers to a continuing education effort of teachers in the field of teacher education. Teacher professional development can take place in several ways: courses, workshops, independent research, group-work initiatives, and sometimes even exchanging ideas with a colleague in the staff room. In light of these, professional development experiences of pre-service teachers emerged during the current study with the following subthemes: generic skills development, and better career outcomes.

Most students commented on the fact that digital literacy, academic writing, and information literacy are skills teachers need to learn to broaden their perspectives of life and profession in the 21st century. In this regard, students generally remarked that the course at this university made contributions to their generic skills. One of the students said:

My academic writing skill is by far the one improved the most because we created our own blog page and shared our weekly learning outcomes with our instructors. Because of this, I was very careful while writing my blog entries and I paid attention to my grammar mistakes. Day by day, I realized that my writing skills improved as I was trying to write like a professional (P56, Survey).

Several students also underlined that they felt digitally competent in terms of seeking, analyzing, and producing information. They mentioned that the course helped them acquire abilities to find, evaluate and use information when needed:

I learnt how to create digital and unique materials for my future students. In order to do this, we had to do research about the platforms or applications we wanted to use. I found the information, reflected on them, then used it to create something new (P27, Reflection paper).

Professional development leads to better career opportunities in the field of education. In this respect, students in the current study believed that the knowledge they acquired during the course is transferable to their future classrooms. Also, they indicated that the benefits of this course are two-fold for their career. First, they thought that the skills they gained would help them find a job. One of the students shared his thoughts in the survey by capitalizing the whole word:

The websites, applications, and plugins that I have learnt in this course will have a crucial place in my teaching life. The atmosphere we experienced -topics, my peers, instructors, Q&A parts- made this course a professional session rather than a simple instruction. So, I feel EQUIPPED (P12, Survey).

Many students also spoke about the changes related to the actions they took and the content they produced on the Internet, such as blogs, websites, and teaching materials after taking the course. They underlined that they started to take into consideration the latest updates related to teaching English and new audiences that emerged after the rise of online education while writing blog entries. They felt that they became a member of a digital society thanks to the guidance they received from course instructors:

I learnt how to create digital materials and communicate digitally. I believe that this course helped me increase my online presence. We achieved this thanks to our blog pages. I am capable of using technology effectively and responsibly in educational contexts. I am planning to continue updating my blog page and I will add it to my CV while applying for a job. Also, I know how to find applications or online training for my professional development. Our instructors have not just taught them but also showed how to do it every week. (P15, Survey).

Secondly, most participants foresaw that the skills they gained at the end of the course will help them design better lessons for their future students. They also spoke about the value of being guided by the course instructors in terms of designing more interactive lessons. One of the participants stated:

Facilitating collaborative learning and designing innovative lessons motivate English language learners. This week we saw how to find topics and digital resources to help our students grasp the knowledge easily. We saw how to attract our students and have more fun even in grammar lessons. I believe that they will help us, especially while teaching writing and listening. I gained very good information about how to use effective and safe platforms (P4, Reflection paper).

Quality of Interaction

According to the data analyzed, the quality of the relationships that learners have in technology-mediated learning environments is mostly related to the interplay between learners and instructors. Within this theme, there were two sub-themes: peer interaction and student-instructor interaction. Peer interaction refers to the interaction between and among the students. The students indicated that they felt a lack of group work and practice opportunities throughout the semester. They said:

I think we needed group work assignments to practice what we learnt and to talk to each other. Group work activities foster collaboration and communication. Once we had a video-making assignment and it was a chance to practice and communicate with each other. It should be given more than once (P6, Survey).

We learnt amazing apps and platforms, but I think it is also very important to experience them first-hand. We should be assigned projects to try them and discuss them to see how we can use them in the best way possible (P28, Survey).

Additionally, most students mentioned the impact that student-instructor interaction had on their learning. Although students thought that the learning environment could have been improved through a combination of student-student interaction and project-based learning, they continued to underline the support they received from the course instructors and the positive atmosphere they experienced in the learning environment. One of the students mentioned the importance of establishing a healthy relationship with the faculty:

Our instructors are role models because we saw that being self-confident and approachable boosts learning. I think the way our instructors behaved allowed us to feel safe, passionate about learning, and connected (P9, Survey).

Student Teachers’ Expectations

Participants also mentioned their expectations of the course. Within this theme, there were two sub-themes: the need for being informed about the platforms and the need for hands-on practice opportunities. The student teachers highlighted the need to have a way to implement course content. One of them said: “We needed practice sessions. Yes, we discussed our ideas, we wrote blog entries and reflection papers, but we did not test whether we could use them or not” (P6, Interview).

Participants also put forward that the learning environment can be fully realized if, and only if, the course provides students hands-on practice opportunities. They described student engagement as a process in which student practice plays a determining role. One participant shared his thoughts as follows:

It was not a big problem to take this course online; however, I and most of my classmates think that one part was missed. This is… practice. I am sure that I learnt amazing things last semester, but I still have questions in my mind whether I will truly implement them in the future. If we did this, I would have felt completely engaged (P12, Interview).

There was also an emerging idea that course practices were beneficial but not enough for student teachers to use them for instructional purposes; thus, they emphasized the need for micro-teaching sessions by saying: “The lesson was delivered online, but it was interactive during the semester, but I think we still need face-to-face one or two sessions to do micro-teachings by using the content we learn” (P4, Interview).

Discussion

VLEs have become increasingly important in education, particularly as a result of the widespread adoption of distance and online learning (Alves et al., 2023). In this study, the participants were a group of pre-service English language teachers who reported having a high level of familiarity and competence with computers, internet usage, and openness to new digital technologies. However, their level of social network engagement was found to be lower compared to these other areas of digital proficiency. Although none of the participants assessed themselves as having an A1 level of digital competence, more than a quarter reported having a B1 level of competence. The remaining participants, or 58% of the group, stated that their level of digital competency was at least B2.

The findings of this study are consistent with earlier studies indicating that pre-service English language teachers tend to have a high level of digital competence, particularly in areas such as computer usage and internet literacy (Haşlaman et al., 2024). This finding is in line with those in the context of VLEs, where these skills are considered necessary for effective engagement with online course materials and communication with instructors and classmates (Thornton, 2016). However, the finding related to the social network engagement was lower compared to other domains of digital proficiency among the pre-service teachers in this study may indicate that there is room for improvement in terms of using social media as a tool for self-learning. In fact, previous research has suggested that pre-service teachers tend to have lower levels of social media use compared to other groups of students (Calderón-Garrido & Gil-Fernández, 2023). It may be worth considering strategies to encourage greater use of social media as a learning tool in VLEs, such as providing training or support for using these platforms effectively (Ansari & Khan, 2020). More importantly and related to our scope, it is worth noting that the majority of participants in this study reported having a B2 or higher level of digital competence according to SELFIE for TEACHERS self-assessment tool, aligning with other research findings indicating that pre-service teachers generally have a high level of digital literacy (Liza & Andriyanti, 2020). It is recommended to consider these points when discussing the following discourse.

This study found that course content plays an important role in providing pre-service teachers with opportunities to put theory into practice, while also encouraging students to actively engage with the material (Randi, 2004). In accordance with the adapted model of Student Learning Process framework provided in the literature review, these opportunities enable them to be involved in the learning process (Biggs et al., 1999). It is mentioned several times by the participants that course content should aim to increase the level of teacher competence in accessing information more rigorously and precisely fast and safe, producing learning materials to promote learning in the class, and keeping up with new trends in English language teaching. Therefore, taking into consideration students’ needs and interests while designing the course content helps course instructors set up beneficial online learning environments. Also, it was mentioned by the participants that the course syllabus should include topics that draw student teachers’ attention to different aspects of the use of technology in English language teaching. In addition to this, this study found that writing reflective pieces and blog entries is one of the practical ways of engaging in theory, rethinking it, and sharing experiences with other professionals. Pennington and Richards (2016) also argue that such reflective writing in teacher education programs is very beneficial. Furthermore, the participants implied that they felt more competent in using technology for educational purposes at the end of the course. They also highlighted the importance of learning how to integrate technology with language teaching. The tasks assigned considerably improved their academic writing, digital literacy, and 21st century skills. Developing these skills is crucial as they include critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, and communication, which are essential for success in the modern, interconnected world. Additionally, such skills were found to be enhanced in technology-enhanced learning environments, which provide opportunities for interactive and engaging learning experiences (Oskoz & Elola, 2014).

Participants hold the view that maintaining positive relationships with course instructors, receiving supportive teaching and academic guidance, and being in a healthy learning environment were factors that contributed to student motivation and success in the course. Though student motivation can be influenced by factors other than the learning environment or the instructor, such as individual student characteristics and prior knowledge (Pintrich & Schunk, 2002), a positive learning environment has been found to foster student motivation and academic achievement (Ferrer et al., 2022; Sutarni et al., 2021). Student success in online courses may depend on more than just the quality of the learning environment or the instructor’s teaching style (Vo & Ho, 2024). From a more positive point of view, research has shown that a supportive teaching style can lead to increased student engagement and learning outcomes (Gage & Berliner, 1988). In addition to those, developing good relationships with instructors has been linked to increased student satisfaction and retention in online courses (Shelton & Saltsman, 2004).

According to the participants in the study, the learning environment was perceived as professional and helpful, and the skills acquired at the end of the course prepared them for using technology in their future classrooms. The participants reported that learning practical and student-centered topics would enable them to design engaging lessons for their future students. Even those participants who initially felt less competent in using technology reported feeling like part of a digital society after completing the course. The positive and understanding attitude of the course instructors towards the learning environment was found to enhance student self-confidence, increase student engagement, and facilitate learning, according to the participants. Studies have consistently found that a positive and supportive learning environment can have a positive impact on engagement, supportive teaching style and academic achievement (Gage & Berliner, 1988; Wang & Eccles, 2013).

Finally, some suggestions were offered by the participants for improving both the content and delivery of the course. First, although they appreciated the technology-mediated and stress-free learning environment, they still thought that more time and space should be devoted to practice in the course syllabus. Especially, the lack of group work activities and teaching opportunities led to decreased student-student interaction in the course. Besides, the participants were willing to experience technology first-hand, carry out small-scale projects, and prepare micro-teaching lessons by utilizing the websites, applications, and plug-ins they learnt.

In this study, the objective was to explore pre-service EFL teachers’ experiences in a collaborative synchronous online learning environment. The findings revealed that the success of the collaborative online course on Instructional Technologies was closely linked to participants’ engagement, interaction with peers and instructors, and professional development. While the participants reported overall satisfaction with the course experience, including the course content, instructors’ attitudes, and teaching organization, they identified the need for practical application of the tools presented during the course. Additionally, the participants expressed a high level of engagement due to the challenging nature of the course content, which required continuous attention and offered opportunities for deep learning through the process of reflection (King, 2011). Although these aspects of instruction are not novel, the instructors’ role in facilitating the learning environment was critical in this study. The instructors worked in harmony and collaboration, which affected the learning process positively and fostered a sense of self-confidence and attentiveness among participants. Moreover, the participants acknowledged that acquiring knowledge about emerging technologies and engaging in regular reflection would enhance their career prospects.

Conclusion

The experiences of pre-service EFL teachers in a collaborative, synchronous online learning environment are presented in this study. Based on the findings, participants’ engagement, interaction, and professional development can all be greatly improved in such an environment. Instructors played a crucial role in creating an optimal learning setting, highlighting the significance of the instructors’ interaction with students both within and outside of the classroom. Last but not least, the participants’ acknowledgement of the importance of emerging technology and reflective practice underscores the possibility of introducing these components into other EFL teacher preparation programs.

Limitations, Implications and Future Research

The findings may not be applicable to all student language teachers in other educational settings or countries owing to the specific context of Turkey. The data collected through self-reported measures, such as weekly reflection papers, online surveys, and one-on-one interviews may be subject to bias or inaccuracies, which could affect the reliability and validity of the findings (Tempelaar et al., 2020).

One delimitation is that the study only includes qualitative data, and does not include the instructors’ or other stakeholders’ perspectives.

Despite these potential limitations, the findings of this study may offer some valuable implications for the impact of collaborative online courses on pre-service English language teachers’ engagement, interaction, learning and professional development.

Future research may further explore the long-term effects of such courses, as well as the effectiveness of different instructional approaches and technologies in collaborative online learning environments.

Notes on the Contributors

Dr. Cemil Gökhan Karacan is an Assistant Professor in the English Language & Literature at Beykent University. He is an alumnus of the English Language Teaching program at Istanbul University and obtained both his master’s degree and PhD in the same field from Bahçeşehir University. Dr. Karacan’s research primarily focuses on pre-service language teacher education and digital competence for educators. A technology enthusiast, he has a particular interest in technology-assisted language instruction, with a specific emphasis on the utilization of augmented reality in language learning and teaching. He has published numerous research studies on a variety of topics, predominantly related to technology in education.

Dr. Melike Bekereci-Şahin received her M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in English Language Teaching from Middle East Technical University, Ankara. She has worked as a research assistant, English language teacher, English language instructor, and assistant professor in different institutions. Her research interests include English language teacher education, professional identity, practicum, and rural education.

Statements and Declarations

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our dear participants who devoted their time and effort for this study.

References

Ak, Ş., & Gökdaş, İ. (2021). Comparison of pre-service teachers’ teaching experiences in virtual classroom and face-to-face teaching environment. Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, 12(1), 1–23.

Artino, A. R., & Stephens, J. M. (2009). Academic motivation and self–regulation: A comparative analysis of undergraduate and graduate students learning online. The Internet and Higher Education, 12(3–4), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.10.002

Alves, P., Miranda, L., & Morais, C. (2023). The importance of virtual learning environments in higher education. In D. Fonseca & E. Redondo (Eds.), Handbook of research on applied e-learning in engineering and architecture education (pp. 404–425). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-8803-2.ch018

Ansari, J. A. N., & Khan, N. A. (2020). Exploring the role of social media in collaborative learning: The new domain of learning. Smart Learning Environments, 7(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-020-00118-7

Aworuwa, B., & Owen, R. (2009). Learning outcomes across instructional delivery modes. In P. Rogers, G. Berg, J. Boettcher, C. Howard, L. Justice, & K. Schenk (Eds.), Encyclopedia of distance learning (2nd ed., pp. 1363–1368). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-198-8.ch195

Baker, R. S., D’Mello, S. K., Rodrigo, M. M. T., & Graesser, A. C. (2010). Better to be frustrated than bored: The incidence, persistence, and impact of learners’ cognitive–affective states during interactions with three different computer–based learning environments. International Journal of Human–Computer Studies, 68(4), 223–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2009.12.003

Biggs, J. (1999). What the student does: Teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research & Development, 18(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436990180105

Borba, M. C., Chiari, A. S. D. S., & de Almeida, H. R. F. L. (2018). Interactions in virtual learning environments: New roles for digital technology. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 98, 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-018-9812-9

Bozkurt, A., & Sharma, R. C. (2020). Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to CoronaVirus pandemic. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3778083

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690300200201

Calderón-Garrido, D., & Gil-Fernández, R. (2023). Pre-service teachers’ use of general social networking sites linked to current scenarios: Nature and characteristics. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 28(3), 1325–1349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-022-09560-1

Can, T., & Simsek, I. (2015). The use of 3d virtual learning environments in training foreign language pre–service teachers. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 16(4), 114–124. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.53012

Chao, P. C., Wen, T. H., Ching, G. S., Roberts, A., & Zuo, Y. (2024, May). Compassion fatigue among pre-service teachers during online learning and its relationship with resilience, optimism, pessimism, social and emotional learning, and online learning efficacy. In L. Uden & D., Liberona (Eds.), Learning Technology for Education Challenges. LTEC 2024. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 2082. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-61678-5_15

Chi Vo, L., Mounoud, E., & Rose, J. (2012). Dealing with the opposition of rigor and relevance from Dewey’s pragmatist perspective. M@ n@ gement, (4), 368–390. https://doi.org/10.3917/mana.154.0368

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and education: The self–determination perspective. Educational Psychologist, 26(3–4), 325–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.1991.9653137

Debbag, M., & Fidan, M. (2022). Examining pre-service teachers’ perceptions about virtual classrooms in online learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 23(3), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v23i3.5925

Gage, N. L., & Berliner, D. C. (1988). The role of the teacher in shaping classroom climates that foster student learning and personal development. In N. L. Gage & D. C. Berliner (Eds.), Educational psychology (pp. 714–755). Houghton Mifflin.

Graetz, K. A. (2006). The psychology of learning environments. Educause Review, 41(6), 60–75.

ElSayad, G. (2023). Higher education students’ learning perception in the blended learning community of inquiry. Journal of Computers in Education, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-023-00290-y

Ferrer, J., Ringer, A., Saville, K., A Parris, M., & Kashi, K. (2022). Students’ motivation and engagement in higher education: The importance of attitude to online learning. Higher Education, 83(2), 317–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00657-5

Haşlaman, T., Atman Uslu, N., & Mumcu, F. (2024). Development and in-depth investigation of pre-service teachers’ digital competencies based on DigCompEdu: A case study. Quality & Quantity, 58(1), 961–986. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11135-023-01674-z

Herrington, A., & Herrington, J. (2006). What is an authentic learning environment? In T. Herrington & J. Herrington (Eds.), Authentic learning environments in higher education (pp. 1–14). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-59140-594-8.ch001

Hrastinski, S. (2008). Asynchronous and synchronous e–learning. Educause Quarterly, 31(4), 51–55. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2008/11/asynchronous-and-synchronous-elearning

Huang, R., Liu, D. J., Tlili, A., Yang, J., & Wang, H. (2020). Handbook on facilitating flexible learning during educational disruption: The Chinese experience in maintaining undisrupted learning in COVID–19 outbreak. Beijing: Smart Learning Institute of Beijing Normal University, 46.

Jaggars, S. S. (2014). Choosing between online and face–to–face courses: Community college student voices. American Journal of Distance Education, 28(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2014.867697

Jiang, R. (2022). Understanding, Investigating, and promoting deep learning in language education: A survey on Chinese college students’ deep learning in the online EFL teaching context. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 955565. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.955565

Kaufmann, R., & Vallade, J. I. (2022). Exploring connections in the online learning environment: student perceptions of rapport, climate, and loneliness. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(10), 1794–1808. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1749670

Ke, F., & Xie, K. (2009). Toward deep learning for adult students in online courses. The Internet and Higher Education, 12(3–4), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.08.001

Kennedy, D. M. (2016). Is it any clearer? Generic qualitative inquiry and the VSAIEEDC model of data analysis. The Qualitative Report, 21(8), 1369–1379. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2444

King, C. (2011). Fostering self-directed learning through guided tasks and learner reflection. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 2(4), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.37237/020403

Liza, K., & Andriyanti, E. (2020). Digital literacy scale of English pre-service teachers and their perceived readiness toward the application of digital technologies. Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn), 14(1), 74–79. https://doi.org/10.11591/edulearn.v14i1.13925

Marton, F., & Säljö, R. (1976). On qualitative differences in learning: I—Outcome and process. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1976.tb02980.x

Mimirinis, M., & Bhattacharya, M. (2007). Design of virtual learning environments for deep learning. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 18(1), 55–64.

Morse, J. M., Barrett, M., Mayan, M., Olson, K., & Spiers, J. (2002). Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690200100202

Ni, C., Liu, X., Hua, Q., Lv, A., Wang, B., & Yan, Y. (2010). Relationship between coping, self–esteem, individual factors and mental health among Chinese nursing students: A matched case–control study. Nurse Education Today, 30(4), 338–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2009.09.003

Nissim, Y., Weissblueth, E., Scott–Webber, L., & Amar, S. (2016). The effect of a stimulating learning environment on pre–service teachers’ motivation and 21st century skills. Journal of Education and Learning, 5(3), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v5n3p29

Oskoz, A., & Elola, I. (2014). Integrating digital stories in the writing class: Towards a 21st century literacy. In J. P. Guikema & L. Williams (Eds.), Digital literacies in foreign language education: Research, perspectives, and best practices (pp. 179–200). CALICO.

Özüdoğru, M. (2021). Pre–service teachers’ perceptions related to the distance teacher education learning environment and community of inquiry. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 5(4), 43–61. https://doi.org/10.33902/JPR.2021472945

Pai, P. G., Menezes, V., Subramanian, A. M., & Shenoy, J. P. (2014). Medical students’ perception of their educational environment. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR, 8(1), 103-107. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/5559.3944

Pennington, M. C., & Richards, J. C. (2016). Teacher identity in language teaching: Integrating personal, contextual, and professional factors. RELC Journal, 47(1), 5-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688216631219

Percy, W. H., Kostere, K., & Kostere, S. (2015). Generic qualitative research in psychology. The Qualitative Report, 20(2), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2097

Persson, R. S. (2006). VSAIEEDC–A cognition–based generic model for qualitative data analysis in giftedness and talent research. Gifted and Talented International, 21(2), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332276.2006.11673473

Pintrich, P. R., & Schunk, D. H. (2002). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications (2nd ed.). Merrill.

Randi, J. (2004). Teachers as self–regulated learners. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 106(9), 1825–1853. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2004.00407.x

Sande, B., & Burnett, C. S. (2023). Designing learning environments that support diverse students’ needs in a teacher education program. International Journal of Teacher Education and Professional Development (IJTEPD), 6(1), 1–24.

Shelton, K., & Saltsman, G. (2004). The dotcom bust: A postmortem lesson for online education. Distance Learning, 1(1), 19–24.

Sutarni, N., Ramdhany, M. A., Hufad, A., & Kurniawan, E. (2021). Self-regulated learning and digital learning environment: Its effect on academic achievement during the pandemic. Cakrawala Pendidikan [Educational Horizon], 40(2), 374–388. https://doi.org/10.21831/cp.v40i2.40718

Syah, M. F. J., Harsono, Prayitno H. J., & Fajriyah, D. S. (2020). The 21st century skills of prospective teacher students in the industrial revolution 4.0 era (the adaptation and problem-solving skill). Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1470, 012054. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1470/1/012054

Tempelaar, D., Rienties, B., & Nguyen, Q. (2020). Subjective data, objective data and the role of bias in predictive modelling: Lessons from a dispositional learning analytics application. PLOS ONE, 15(6), e0233977. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233977

Thornton, K. (2016). Promoting engagement with language learning spaces: How to attract users and create a community of practice. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(3), 297–300. https://doi.org/10.37237/070303

Thomas, P., & Bain, J. (1984). Contextual dependence of learning approaches. Human Learning, 3(4), 230–242.

Vo, H., & Ho, H. (2024). Online learning environment and student engagement: The mediating role of expectancy and task value beliefs. The Australian Educational Researcher, 51(5), 2183-2207.

Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2013). School context, achievement motivation, and academic engagement: A longitudinal study of school engagement using a multidimensional perspective. Learning and Instruction, 28, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.04.002Yılmaz-Na, E., & Sönmez, E. (2023). Unfolding the potential of computer-assisted argument mapping practices for promoting self-regulation of learning and problem-solving skills of pre-service teachers and their relationship. Computers & Education, 193, 104683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104683