Siti Zuhaida Hussein, Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

Rosnita Hashim, Nursing/ Faculty of Medicine, University Kebangsaan Malaysia

Siti Suria Salim, Basic Education, Universiti Putra Malaysia

Maziah Ahmad Marzuki, Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

Hussein, S. Z., Hasham, R., Salim, S. S., & Marzuki, M. A. (2025). Self-directed learning, friendship quality, and learning styles among undergraduate students in a public university. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal (60–75). https://doi.org/10.37237/202406

Published online first on 22 November 2024

Abstract

Independent learning can be challenging, even for highly skilled and motivated individuals. This study examined the learning preferences, friendship quality, and self-directed learning of undergraduate students. A cross-sectional descriptive survey was conducted with 290 respondents at a public university in Malaysia. Stratified random sampling was used, with the sample size for each stratum proportional to the measurement of the study. The survey questionnaire comprised the school inventory model, friendship quality inventory, and Self-Directed Learning Readiness Scale (SDLRS). The study revealed the surface-type learning style had the highest mean value (M=3.20), and the highest friendship quality was intimacy (M=3.17). 55% of students had a moderate level of self-directed learning. There was a significant relationship between self-directed learning and learning style (b = 0.52, p < 0.05) and friendship quality (b = 0.13, p < 0.05). The findings of this study also provide an opportunity for self-learning readiness in the context of teaching and learning through cooperation to achieve lifelong self-sufficiency in the need for knowledge and skills.

Keywords: self-directed learning, learning style, quality of friendship

In today’s fast-evolving world, marked by globalization and technological advancements, self-directed learning (SDL) has emerged as a crucial competency necessary for individuals to thrive in the twenty-first century. SDL is a student-centered approach that promotes independent learning and enhances the quality of education without replacing traditional classroom teaching (Loeng, 2020; Nasri & Mansor, 2006). A more accurate definition of SDL is that it is a process in which individuals take the initiative in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating goals, identifying resources, and evaluating their learning outcomes, often occurring outside of formal educational settings (Charokar & Dulloo, 2022). In the digital age, SDL has gained significant importance and can be implemented in various ways to facilitate effective learning (Maung & Abdullah, 2007; Win & Ahmad, 2023). SDL is a valuable tool for personal development, offering engaging learning experiences beyond traditional lectures and fostering student independence (Hutasuhut, 2023; Robinson & Persky, 2020). Loeng (2020) explains that SDL enhances interactivity by encouraging students to take control of their learning process, engage actively with materials, and seek out resources independently. This approach fosters greater autonomy as students set their own goals, manage their time, and assess their progress, leading to a more personalized and involved learning experience.

The impact of SDL extends beyond academic progress because it prepares students with the skills necessary to navigate an increasingly interconnected and borderless society (Brookfield, 2009; van der Walt, 2019). Notably, SDL is enhanced when social interaction and friendship are incorporated, as these characteristics provide a supportive learning environment. Within SDL, group members share responsibilities for assignments, personal growth, and knowledge acquisition, fostering natural friendships and boosting confidence (Yusri et al., 2012).

Friendship quality can impact an individual’s motivation and ability to engage in SDL through emotional support, collaborative learning opportunities, accountability and goal setting, social learning and modeling, constructive feedback, and critical thinking (Berndt, 2002). Friends who provide encouragement and believe in an individual’s abilities can enhance motivation and happiness by fostering self-worth, confidence, and resilience, leading to a more positive learning experience (Sharma & Parveen, 2021).

Collaborative learning with friends sharing similar interests enhances the learning experience. Moreover, friendships provide emotional support during challenging times, aid in coping, and create a sense of community (Sharma & Parveen, 2021). Observing friends engaged in SDL can inspire individuals to embark on their own learning journeys, while constructive feedback from friends promotes intellectual growth and enhances the quality of SDL (Berndt, 1999; Lei et al., 2012). Enhancing SDL in higher education institutions has been recognized as a pressing need, with studies suggesting that effective implementation of SDL leads to consistent academic performance among students (Sukseomung, 2009).

Engaging in SDL can lead to personal growth and enhance the quality of friendships. Despite the challenges posed by the pandemic, there is potential for mutual reinforcement between SDL and friendship quality. Friendships have adapted to virtual settings by offering support, motivation, and collaborative learning opportunities (Wright & Wachs, 2023). Reliable information sharing has been emphasized, with friends helping each other navigate and critically evaluate COVID-19-related information.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted SDL and friendship quality. Remote learning and distance learning are often used interchangeably, both involve learning outside of a traditional classroom. Remote and distance learning have emphasized the significance of SDL skills by necessitating that students take initiative and responsibility for enhancing their digital literacy and education. SDL fosters critical and independent thinking as students tackle challenges and develop problem-solving abilities. With reduced supervision, they are required to manage their time and resources efficiently, promoting autonomy and self-motivation. The lack of in-person interactions has hindered the formation and deepening of friendships. However, friendships can positively influence SDL by providing support, motivation, and collaboration (Senior & Howard, 2014; Sun et al., 2022). There is still room to study the relationship between friendship quality, learning style, and undergraduate SDL. An investigation into this knowledge gap is warranted because it has the potential to shed light on key aspects that influence students’ academic achievement and preparedness for SDL.

This emphasis on SDL aligns with the educational goals of the international education systems, including Malaysia (Nasri & Mansor, 2006). Despite the importance of SDL in Malaysian education, challenges still need to be addressed, such as the need for students to develop effective SDL strategies (Hutasuhut et al., 2023). Guided learning approaches have positively affected students’ self-directedness and SDL levels (Hutasuhut et al., 2023). Additionally, while existing research has extensively explored educators’ perspectives on SDL, more studies are needed to investigate SDL in undergraduate students (Ibrahim et al., 2017; Nasri & Mansor, 2006). Hence, further investigation is warranted to study the connection between learning styles, friendship quality, and SDL, particularly among undergraduate students. In light of these gaps in the literature, this study aimed to examine undergraduate students’ learning styles, friendship quality, and SDL.

Research Questions

The study intends to answer the following research questions:

- How do the students practice SDL?

- What are the learning styles and quality of friendships of undergraduate students?

- What is the relationship between learning style, friendship quality, and SDL among undergraduate students?

Methodology

This study is a cross-sectional survey to examine the learning style, friendship quality, and SDL of 290 undergraduate students at a public university in Selangor, Malaysia. The study population consisted of students from years 1 to 4 of Economics and Management at a public university. The inclusion criteria were students who were able to understand English. In this study, understanding English was defined as the ability to comprehend written and spoken English for following study instruction only. Students who had postponed their education and those who were on prolonged medical leave at the time of data collection met the exclusion criteria. To address this issue, the researcher required a complete list of students for each year. Since the population of this study is known, the desired sample size was calculated using the Krejcie and Morgan (1970) formula. As the population size increased, the sample size also increased.

This research utilized a stratified random sampling technique. The population was categorized into strata based on the students’ year of study, with the sample size for each stratum reflecting the proportions of the study program, which included undergraduate students selected at random according to these strata. This method ensures that each individual within a subset has an equal opportunity to be included (Rutberg & Bouikidis, 2018; Thomas, 2021). By employing stratified random sampling, the study minimizes selection bias and ensures comprehensive representation of the population in the data (Suresh, 2022). This approach includes all segments, contributing to more dependable outcomes. However, it may not be ideal for populations with limited distinguishing characteristics that can be used to create separate units. To address this limitation, the researcher needed to compile a detailed list of students enrolled in each course.

Research Instruments

This study uses a three-part questionnaire as a research tool consisting of the School Inventory model, the Friendship Quality Inventory, and the SDL Readiness Scale. The questionnaire used a Likert scale format, where participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with each statement. In this study, the value of Cronbach’s alpha for learning style was 0.86 for all items (28), friendship quality was 0.89 for 21 items, and SDL was 0.87 for 18 items.

School Inventory Model

In Part one, the School Inventory model was adapted in this study to identify the learning styles that respondents practice. This instrument, which was created by Selmes (1987), has 28 items that Norlia et al. (2006) adjusted to account for regional variations in climate and linguistic patterns. The school inventory model has five characteristics: surface (observable elements such as rules and layout), deep (underlying values and norms), planned (strategic initiatives), perseverance (long-term commitment), and reactive (response to challenges). Furthermore, the 28 items for the five characteristics were distributed as follows: surface (8 items), deep (8 items), planned (5 items), and perseverance (7 items). This instrument used a four-point Likert scale, “from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). The Cronbach’s alpha values for the overall scale were 0.86, which was considered good for internal consistency. These dimensions provide a complete picture of a school’s environment and operations.

Friendship Quality Inventory (FQUA)

Part two employed the Friendship Quality Inventory (FQUA), adapted by Thien et al. (2012), to measure four key dimensions of friendship quality. According to Thien et al. (2012), these dimensions include: safety (the level of confidence or trust relied on friends), intimacy (the level of emotional closeness and attachment to friends), acceptance (students being accepted by their friends either socially or emotionally), and help (support and assistance within the friendship). These dimensions collectively assess the overall quality and depth of friendships. Respondents rated 20 items divided across these four dimensions using a four-point Likert scale. The Cronbach’s Alpha value for the overall friendship quality was 0.89 for 21 items, which is considered good for internal consistency.

Self-Directed Learning Readiness Scale (SDLRS)

Part three is a questionnaire regarding , which has 18 items (self-management (6 items), willingness to learn (6 items) and self-control (6 items). This questionnaire was adapted from the SDLRS inventory by Guglielmino (1997). Mat Daud et al. (2015) adjusted this questionnaire to account for regional variations in climate and linguistic patterns to fit Malaysia’s teaching and learning system. The measurement scale used a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). SDL among the students in this study can be categorized into three levels: low (scores ranging from 10 to 19), moderate (scores ranging from 20 to 29), and high (scores ranging from 30 to 40). The Cronbach’s Alpha value for the overall friendship quality was 0.87 for 18 items, which is considered good for internal consistency.

Data Collection

Researchers used the instrument to investigate and collect information on friendships, quality learning styles, and . The survey was conducted using a questionnaire tailored to the study’s objectives, which was distributed by the researcher to students who were randomly chosen. The respondents were identified using a list of students for each year who voluntarily provided written informed consent to participate in this study. Before starting the study, every respondent was given an explanation of the purpose of the study through an information sheet by the researchers. In this study, the questionnaire was developed in both Bahasa Malaysia and English. Meanwhile, the questionnaire was translated using back-to-back translation to Bahasa Malaysia and this translation tool has a good internal consistency of 0.82.

Additionally, the study’s questionnaire was distributed face-to-face. Despite the option to return the questionnaire by post, most respondents chose to complete it within 20 to 30 minutes and return it to the researcher directly. Participants were requested to complete all questions, and the completed questionnaires were sealed in envelopes for confidentiality before being examined by the researchers.

Data Analysis

This study analyzed the data using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0. This study includes both descriptive and inferential analyses. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethics Considerations

The ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, confidentiality, and anonymity guided this research study and protected its rights. The research ethics committee approved this study prior to its commencement. In addition, each participant in the study provided prior written consent, which included the consent statement and withdrawal information. The written consent was collected through in-person signing of paper forms prior to participation. Respondents also were informed that the participation is voluntary, and respondents can withdraw from the study at any time.

Results

The results showed that the response rate in this study was 100%. In addition, the results revealed that most respondents were female (73.3%), aged between 18 and 21 years (64.3%), and had graduated from matriculation (52%). Furthermore, 39.2% of the respondents were first-year undergraduate students. The sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1. In Malaysia, graduating from matriculation means completing secondary education, often before advancing to higher studies. A diploma, on the other hand, is a post-secondary qualification that typically lasts 1 to 3 years and is offered in various fields, including arts, sciences, engineering, and business, and is commonly awarded by polytechnics, colleges, and universities.

Table 1

Distribution of Socio Demographic Factors (n=290)

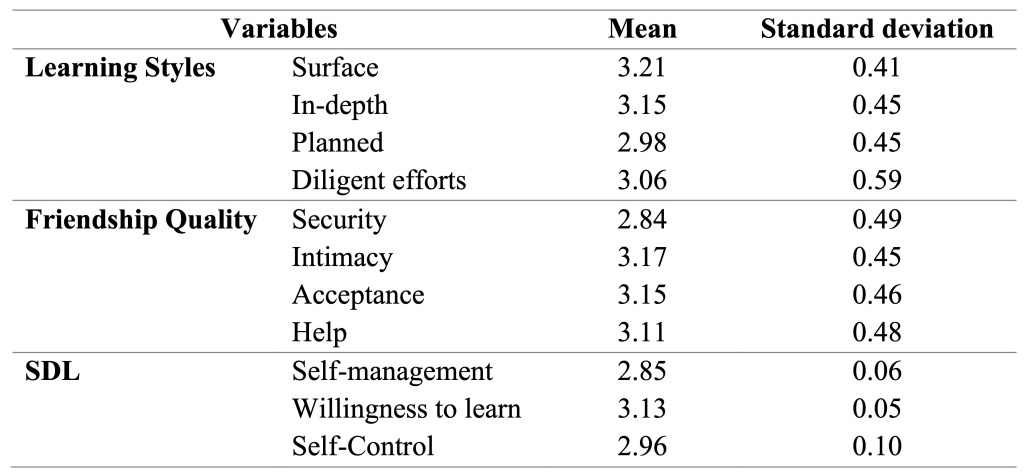

This study evaluated four learning styles using Selmes’s method: surface, in-depth, planned, and diligent. The results showed that the surface learning style had the highest mean value of 3.21, and the planned learning style had the lowest mean value of 2.98. In this study, the highest mean value for friendship quality was 3.17, and the lowest was 2.84, which is related to the safety dimension. Table 2 shows the means for other aspects of friendship quality, such as safety, security, intimacy, acceptance, and help. Moreover, in this study, the highest mean score for SDL was 3.13 (Willingness to learn) and the lowest score was 2.85 (factor Self-management).

Table 2

Learning Style, Quality of Friendship Among Students and SDL (n=290)

The Level of Students’ SDL

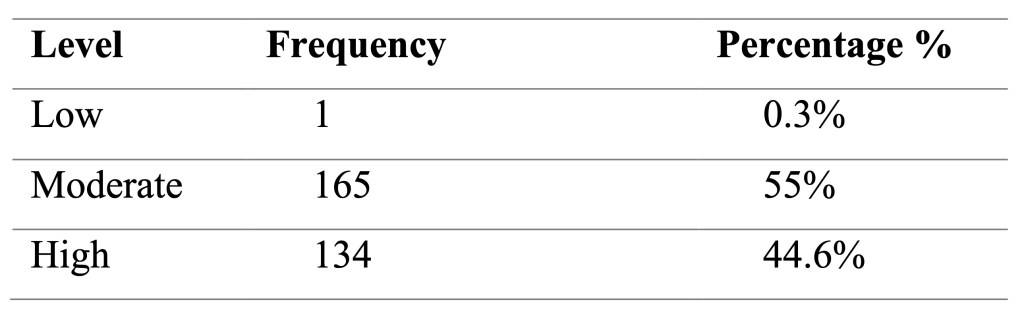

In this study, students’ SDL is classified into three categories, which are self-management, willingness to learn and self-control. The levels are as follows; low (scores between 10 and 19), moderate (scores between 20 and 29), and high (scores between 30 and 40). The analysis found that 55% of students were SDL at a moderate level. However, only one respondent was at a higher level. The students’ SDL is presented in Table 3.

Table 3

The Level of Students’ SDL (n=290)

| Level | Frequency | Percentage % |

| Low | 1 | 0.3% |

| Moderate | 165 | 55% |

| High | 134 | 44.6% |

The results of the study revealed that learning style (b = 0.52, p < 0.05) and friendship quality (b = 0.13, p < 0.05) have a significant relationship with SDL. Concerning the beta value, every one-unit change in learning style causes 0.52 units of SDL. Meanwhile, 0.13 units of SDL are affected by every unit of change in friendship quality (Table 4).

Table 4

Regression Model (n=290)

Discussion

This research was a quantitative cross-sectional survey carried out at public institutions in Selangor, Malaysia, to investigate undergraduate students’ learning styles, the quality of their friendships, and their level of SDL. In this survey, most undergraduate students adopted a surface learning style and a deep, deliberate, and diligent style. Although the surface type had the highest mean score, the mean difference in each learning style was slight, indicating that the students in this study adopted various learning styles and did not focus on just one style. Similar to the results of this study, Norlia et al. (2006) conducted a correlation study that discovered a significant relationship between deep learning styles and persistent, organized intrinsic motivation among Malaysian students. Norlia et al.’s study involved 350 secondary students from 28 schools across Peninsular Malaysia.

On the other hand, kinesthetic learning is the dominant learning style among Taibah students (Aljohani & Fadila, 2018). This is not surprising, as previous studies have found a strong correlation between participants’ learning preferences and measures of SDL readiness (Aljohani & Fadila, 2018). Nonetheless, the interpersonal skills component has had the highest average in recent years, while the learning technique dimension has the lowest average (Oktaviani et al., 2021).

The findings of this study indicate that the quality of friendship, measured by the degree of intimacy, had the highest mean value, while safety aspects were rated lowest. This suggests that students value intimacy over safety, highlighting the role of trust and loyalty in their friendships. Furthermore, there was a significant relationship between student learning styles and friendship quality with SDL. This closeness in friendships may be due to trust and loyalty. Students were determined to study but managed their time well with their friends. As researchers, we believe that students learn more effectively when paired with peers, as this collaboration enhances their understanding, improves retention, and helps to prevent boredom. Similarly, Yusri et al. (2012) emphasized the importance of a supportive peer network in learning. They noted that Malaysian students studying Arabic in government universities heavily utilized peer learning strategies, significantly benefiting from collaboration in group activities. Meanwhile, Aljohani and Fadila (2018) conducted a study among undergraduate nursing students at Taibah University in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia, revealing a significant relationship between learning styles and readiness for SDL. Indeed, Ghazali et al. (2012) highlighted the importance of a supportive peer network among students. In our opinion, students who spend time with friends could manage their time better and learn more when paired with peers, improving understanding, retention, and engagement.

In this study, respondents rated their level of SDL, with more than half indicating a moderate level, likely reflecting the educational context and available support structures. The findings of this study are similar to those of a study conducted in Malaysia, in which the level of SDL among undergraduate students was high to moderate (Mat Daud et al., 2023; Ahmad et al., 2023). Ahmad et al. (2023) suggested by providing additional resources and support for SDL and creating a conducive learning environment to encourage SDL. The findings of this study were similar to a survey of undergraduate students in Indonesia, where their level of SDL was moderate, characterized by self-control, strong interpersonal skills, and determination to learn (Oktaviani et al., 2021). In contrast, several surveys recorded high SDL levels among undergraduate students in Ankara (Tekkol & Demiral, 2018). Additionally, SDL skills were found to have a moderately positive relationship with lifelong learning tendencies, indicating that these students were well-prepared for SDL (Aljohani & Fadila, 2018; El-Gilany & Abusaad, 2013; Safavi et al., 2010). Thus, we hypothesized that encouraging students to participate in SDL would improve their academic performance.

In contrast, Maung and Abdullah (2007) reported no significant difference between learning styles and SDL, discovering that male students rated their appreciation of SDL significantly higher than female students. Maung and Abdullah (2007) surveyed undergraduate students at a university in Malaysia and noted that appreciation of SDL and the utilization of university resources were positive, regardless of learning style.

Higher self-direction readiness levels enable people to choose their learning objectives, activities, and sources more skillfully (Loeng, 2020). Thus, preparing a stimulating learning environment can increase students’ engagement in SDL learning. Clear instructional goals, workload-appropriate examinations, and an emphasis on independence also significantly aid students in enhancing their academic performance in the subsequent SDL process. (Din et al., 2018; Robinson & Persky, 2020). By contrast, Nasir and Mansor (2016) believe that a more comprehensive understanding of SDL is required. This approach should acknowledge the sociocultural milieu’s influence on SDL and the significant role that the individual and educator play in the process. LeBlanc (2018) and Newton and Miah (2017) recommended that teachers teach students to use deliberate learning strategies instead of promoting learning styles. Elshami et al. (2022) emphasizes that SDL and techno-pedagogical skills are important for faculty and students.

These recommendations emphasize the need to assist students in transitioning from traditional educational approaches to those that prioritize critical thinking, self-direction, and collaboration as central learning strategies. Additionally, to promote lifelong independence in acquiring knowledge and skills, teachers and students should collaborate to actively seek opportunities for SDL within the teaching-learning setting.

Implications

The findings of this study underscore the importance of SDL in preparing students for success in a rapidly evolving global landscape. As SDL emerges as a critical competency, educators must recognize its role in enhancing educational quality while complementing traditional teaching methods. This implies that educators should actively promote SDL by encouraging students to take initiative in their learning processes, fostering independence and engagement. Moreover, the study highlights the significant influence of friendship quality and learning styles on SDL. Educators should focus on creating a supportive learning environment that nurtures positive peer relationships, as these friendships can enhance motivation and collaboration in learning. Educators can help students develop essential skills for SDL by facilitating opportunities for social interaction and teamwork.

In addition, recognizing diverse learning styles is crucial. Educators should adopt varied teaching strategies that cater to different learning preferences, thereby enhancing students’ ability to engage with materials and achieve their learning goals. This approach not only supports the development of SDL but also contributes to students’ overall personal growth and academic success.

Conclusion

In summary, the results indicate a significant relationship between learning styles and SDL. Most participants are female and exhibit surface learning styles, emphasizing a high value on friendship qualities such as intimacy and acceptance. Educators can recognize that promoting healthy competition and supportive peer relationships fosters friendship and mutual respect among students, leading to deeper connections. This supportive environment enhances SDL by cultivating a sense of belonging and trust. By embracing diverse learning styles and varied teaching methods, educators can help students develop effective SDL strategies, ultimately fostering both academic success and social growth.

Notes on the Contributors

Siti Zuhaida Hussein is a senior nursing lecturer at the Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Her research focuses on public health nursing, nursing education, and the development of best practices in patient care. Her contributions to this study include writing the introduction, literature review, discussion, original draft preparation, and serving as the corresponding author.

Rosnita Hashim is a faculty member in nursing at the Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Her interests include clinical nursing practices and enhancing healthcare delivery through education. She was involved in data collection, data analysis, and final draft preparation of the article.

Siti Suria Salim is a senior lecturer in Basic Education at Universiti Putra Malaysia. She specializes in foundational education studies, focusing on educational strategies and early learning methodologies. Her contributions include conceptualization and article writing.

Maziah Ahmad Marzuki is a senior lecturer in nursing at the Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Her research areas include nursing management, educational psychology, technology-enhanced nursing education, neuroscience in nursing education, and children’s health. She contributed to writing the abstract, conclusion, and formatting of this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful and gratefully acknowledge Universiti Putra Malaysia for the support in achieving this work and the Department of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

References

Ahmad, B. E., Saad, Z. A., Aminuddin, A. S., & Abdullah, M. A. (2023). Self-directed learning of Malay undergraduate students. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(3), 244–266. https://doi.org/10.37237/140302

Aljohani, K. A., & Fadila, D. E. (2018). Self-directed learning readiness and learning styles among Taibah nursing students. Saudi Journal of Health Sciences, 7(3), 153–158. https://doi.org/10.4103/sjhs.sjhs_67_18

Berndt, T. J. (1999). Friends’ influence on students’ adjustment to school. Educational Psychologist, 34(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3401_2

Berndt, T. J. (2002). Friendship quality and social development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(1), 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00157

Brookfield, S. D. (2009). Self-directed learning. In R. Maclean & D. Wilson (Eds.), International handbook of education for the changing world of work (pp. 2615–2627). Springer.

Charokar, K., & Dulloo, P. (2022). Self-directed learning theory to practice: A footstep towards the path of being a life-long learner. Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Professionalism, 10(3), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.30476/jamp.2022.94833.1609

Din, N., Haron, S., & Mohd Rashid, R. (2018). Self-directed learning improves quality of life. Journal of Asian Behavioral Studies, 3(10), 154–161. https://doi.org/10.21834/jabs.v3i10.314

El-Gilany, A. H., & Abusaad, F. E. S. (2013). Self-directed learning readiness and learning styles among Saudi undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 33(9), 1040–1044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.05.003

Elshami, W., Taha, M. H., Abdalla, M. E., Abuzaid, M., Saravanan, C., & Al Kawas, S. (2022). Factors that affect student engagement in online learning in health profession education. Nurse Education Today, 110, Article 105261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105261

Ghazali, Y., Nik, M. R., Parilah, M., Wan, H., & Ahmed, T. H., (2012). Penggunaan strategi belajar bersama rakan dalam kalangan pelajar kursus nahasa arab di Universiti Teknologi Mara [The use of peer learning strategies among students of the Arabic grammar course at Universiti Teknologi Mara]. Asia Pacific Journal of Educators and Education, 27, 37–50.

Guglielmino, L. M. (1997). Reliability and validity of the self-directed learning readiness scale and the learning preference assessment. In H. B. Long & Associates (Eds.), Expanding horizons in self-directed learning (pp. 209–222). University of Oklahoma.

Hutasuhut, I. J., Bakar, M. A., Ghani, K. A., & Bilong, D. (2023). Fostering self-directed learning in higher education: The efficacy of guided learning approach among first-year university students in Malaysia. Journal of Cognitive Science and Human Development, 9(1), 221–235. https://doi.org/10.33736/jcshd.5339.2023

Ibrahim, M. M., Arshad, M. Y., Rosli, M. S., & Shukor, N. A. (2017). The roles of teacher and students in self-directed learning process through blended problem-based learning. Sains Humanika, 9(1–4), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11113/sh.v9n1-4.1121

Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

LeBlanc, T. R. (2018). Learning styles: Academic fact or urban myth? A recent review of the literature. Journal of College Academic Support Programs, 1(1), 34–40. https://hdl.handle.net/10877/7914

Lei, M. T., Abdul Razak, N., & Jamil, H. (2012). Friendship quality scale: Conceptualization, development and validation. Paper presented at the Joint AARE-APERA International Conference (December 2–6, 2012). Sydney, Australia. https://pdf4pro.com/amp/view/friendship-quality-scale-conceptualization-development-608c3e.html

Loeng, S. (2020). Self-directed learning: A core concept in adult education. Education Research International, 2020, Article 3816132. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3816132

Mat Daud, K. A., Khidzir, N. Z., & Othman, H. (2015). A self-directed learning readiness instrument. International Journal of Creative Future and Heritage (TENIAT), 3(1), 77–110. https://doi.org/10.47252/teniat.v3i1.257

Maung, M., & Abdullah, A. (2007). Self-directed learning in a higher education environment: Do pre-university education and learning styles play a role? Open University Malaysia. http://library.oum.edu.my/repository/144/1/self-directed_learning.pdf

Nasri, N. M., & Mansor, A. N. (2016). Teacher educators’ perspectives on the sociocultural dimensions of self-directed learning. Creative Education, 7(18), 2755–2773. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2016.718257

Newton, P. M., & Miah, M. (2017). Evidence-based higher education: Is the learning styles ‘myth’ important? Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 444. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.0044

Norlia, A., Subahan, M. M., Lilia, H., & Kamisah, O. (2006). The relationship between motivation, learning style, and additional mathematics achievement of form 4 students. Jurnal Pendidikan, 31, 123–141. http://journalarticle.ukm.my/187/1/1.pdf

Oktaviani, M., Elmanora, E., & Doriza, S. (2021). Students’ self-directed learning and its relation to the independent learning-independent campus program. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Education, Humanities, Health and Agriculture (ICEHHA) (pp. 1–9). https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.3-6-2021.2310919

Robinson, J. D., & Persky, A. M. (2020). Developing self-directed learners. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84(3), 847512. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe847512

Rutberg, S., & Bouikidis, C. D. (2018). Focusing on the fundamentals: A simplistic differentiation between qualitative and quantitative research. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 45(2), 209–212.

Safavi, M., Shooshtari Zadeh, S., Mahmoodi, M., & Yarmohammadian, M. (2010). Self-directed learning readiness and learning styles among nursing students of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Iranian Journal of Medical Education, 10(1), 27–36. http://ijme.mui.ac.ir/article-1-1151-en.html

Sharma, B., & Parveen, A. (2021). A correlational study of friendship quality, self-esteem, and happiness among adolescents. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 9(4), 1669–1676. https://doi.org/10.25215/0904.161

Selmes, L. P. (1987). Improving study skill: Changing perspective in education. Great Britain. Hodder and Stoughton Ltd.

Senior, C., & Howard, C. (2014). Learning in friendship groups: Developing students’ conceptual understanding through social interaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, Article 1031. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01031

Sukseemuang, P. 2009. Self-directedness and academic success of students enrolling in hybrid and traditional courses. Ph.D. Dissertation. Oklahoma University.

Sun, W., Hong, J. C., Dong, Y., Huang, Y., & Fu, Q. (2023). Self-directed learning predicts online learning engagement in higher education mediated by perceived value of knowing learning goals. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 32(2), 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-022-00653-6

Suresh, S. (2022). Nursing research and statistics. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Thien, L. M., Razak, N. A., & Jamil, H. (2012). Friendship quality scale: Conceptualization, development and validation. Australian Association for Research in Education

Tekkol, I. A., & Demiral, M. (2018). An investigation of self-directed learning skills of undergraduate students. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 2324. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02324

Thomas, C. G. (2021). Research methodology and scientific writing (2nd ed.). Springer International Publishing.

van der Walt, J. L. (2019). The term “self-directed learning” – Back to Knowles, or another way to forge ahead? Journal of Research on Christian Education, 28(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10656219.2019.1593265

Win, M. T., & Ahmad, A. (2023). Readiness for self-directed learning among undergraduate students at Asia Metropolitan University in Johor Bahru, Malaysia. Education in Medicine Journal, 15(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.21315/eimj2023.15.1.3

Wright, M. F., & Wachs, S. (2023). Self-isolation and adolescents’ friendship quality: Moderation of technology use for friendship maintenance. Youth & Society, 55(4), 673–685. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X221080484

Yusri, G., Nik Mohd Rahimi, N. R., Parilah, M. S., Wan Haslina, W. H., & Thalal, A. (2012). The use of peer learning strategy among Arabic language course students at Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM). Asia Pacific Journal of Educators and Education, 27, 37–50. http://eprints.usm.my/34601/1/apjee27_2012_ART_3_%2837-50%29.pdf