Behnam Behforouz, Preparatory Studies Center, University of Technology and Applied Sciences, Shinas / Sohar University, Oman. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0078-2757

Ali Al Ghaithi, Foundation Department, Sohar University, Oman. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9653-508X

Behforouz, B., & Al Ghaithi, A. (2025). AI as a language learning facilitator: Examining vocabulary and self-regulation in EFL learners. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(4), 616–634. https://doi.org/10.37237/202507

(First published online October 2025.)

Abstract

This study examined the impact of Copilot, an AI tool, on vocabulary learning and self-regulated learning skills. Through random sampling, 60 Omani English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners were divided into two equal groups, each comprising 30 students. Although both groups received similar in-class training, the experimental group was instructed to use Copilot as an extra facilitator in the learning process. Researcher-made pretest, posttest, and delayed posttest were designed to compare the groups together. Additionally, the experimental group participated in a self-regulated learning survey to measure their autonomy after using Copilot. The study’s findings, based on vocabulary, showed progress in both groups on the posttest, with the experimental group outperforming the control group significantly. While the experimental group maintained high scores during the delayed posttest, the control group’s scores decreased dramatically. Additionally, the analysis of the self-regulated learning questionnaire revealed that using Copilot increased students’ responsibility toward their learning process. The findings are helpful for teachers, students, and institutions.

Keywords: Vocabulary knowledge, self-regulated learning, Artificial Intelligence, Copilot

Acquiring vocabulary is one of the most challenging tasks that learners face in their language studies, especially with limited classroom time and L2 contact outside the classroom. Learning vocabulary is often below expectations for learners studying English, and the implications of having inadequate vocabulary ability may undermine students’ willingness to learn (Gibson, 2016). Technology impacts vocabulary development, expanding learning opportunities outside the classroom. Recent research has demonstrated that technology can enhance vocabulary acquisition by making it more engaging, dynamic, and contextually relevant (Chen et al., 2021; Tu et al., 2020). Artificial intelligence (AI) has enhanced vocabulary acquisition by enabling computers to perform tasks by emulating intelligent human actions, including inference, evaluation, and judgment-making (Hwang et al., 2020). AI can offer multimodal learning material, and deliver tailored feedback (Rad et al., 2023; Wang & Xue, 2024). While conventional digital learning environments may enhance the presentation of multimodal information, AI offers personalised learning resources and tailored learning paths based on student achievement (Diwan et al., 2023). Recent research has explored visual feedback forms, such as image-to-text generative AI, to enhance vocabulary learning (Jia et al., 2022; Shadiev et al., 2020). Despite these developments, these techniques are still pre-defined, restricting prospects for self-directed learning and true use of vocabulary in real-world scenarios (Mercer & Dörnyei, 2020).

Self-regulated learning (SRL) enables students to take control of their learning by setting goals, monitoring progress, and reflecting on their experiences. The advancement of AI in education has created new opportunities for SRL, as intelligent tutoring systems provide learners with feedback and suggestions, enabling them to develop competencies at their own pace (Xia et al., 2023). This integration is becoming increasingly significant as rapid technological advancements require strong self-regulated learning abilities for successful adaptation (Markauskaite et al., 2022).

Recent research emphasises the need for comprehensive implementation methods that consider both the capabilities and limitations of AI technologies in educational contexts (Ateeq et al., 2024). Yang and Kim (2021) noted that there is little empirical evidence to support the usefulness of AI technology in English learning. Furthermore, Chiu (2024) argues that the effects of AI support tools, such as ChatGPT, on student motivation, self-regulated learning (SRL), and need fulfilment are unknown. The Omani higher education system requires students to acquire the English language to move to their specialisation departments; thus, the demand for higher learning autonomy levels is increasing. Additionally, it can be stated that traditional classroom settings often confine learners to engaging in independent learning activities. As mentioned by Benson (2011), increasing the autonomous level of students is essential in EFL environments where there is limited exposure to English-speaking settings outside of formal contexts. Therefore, this study attempts to investigate the effect of the AI tool Copilot as a learning facilitator in an English learning context in Oman. Additionally, the study examines the role of Copilot in enhancing self-regulated learning among Omani EFL learners. The following research questions will be covered thoroughly in this study:

- What is the impact of using Copilot as a facilitator on the vocabulary learning outcomes of Omani EFL learners?

- How does the integration of Copilot influence the self-regulated learning skills of Omani EFL learners?

Literature Review

Mobile-Assisted Vocabulary Learning

Sivabalan and Ali (2022) investigated how learners in higher education can utilise WhatsApp as a technique in MALL to enhance their language abilities. The instructor and the pupils addressed all the terms by giving definitions, discussing pronunciation, exchanging phrases, and completing WhatsApp lexical activities. The findings demonstrated that MALL substantially impacted new word acquisition and increased students’ learning success. Although the study’s outcomes were positive, it did not investigate the durability of vocabulary retention and the learners’ autonomy during the treatment.

Hashemifardnia et al. (2018) investigated how WhatsApp influences vocabulary acquisition among Iranian students. The experimental group utilized WhatsApp to work on the chosen English terms outside of the L2 classroom after obtaining them via the messaging app. In comparison, the control group used a traditional classroom vocabulary learning approach. The research found that the experimental group performed better than the control group. The most significant advantage of this study was its focus on learning beyond the classes, which highlights the benefits of mobile-assisted learning. However, the study did not examine how motivation and learner autonomy contributed to these results. Additionally, it did not investigate vocabulary retention among the students over a longer period.

Bensalem (2018) utilized MALL to investigate the growth of academic English vocabulary. This research included 40 primary learners from the Arabian Gulf State University. The experimental group involved searching for new words in a dictionary, writing a sentence for each word, and sharing the sentences they created via WhatsApp. The control group utilized paper and pencil and the traditional approach to accomplish the identical task as the experimental group. The findings revealed that the experimental group showed a more significant improvement. This study highlights the educational benefits of incorporating digital tools into vocabulary instruction, enhancing learner engagement and developing active vocabulary knowledge. However, it did not measure the long-term usage of such vocabulary knowledge over time. It also did not investigate the self-regulated learning skills of the students outside of the classroom.

Chen et al. (2020) investigated the effect of utilising a chatbot as an additional MALL channel to acquire Chinese in various educational contexts. The control group utilised ChatBot in a one-on-one classroom setting to help them maintain their language. In contrast, the experimental group used a chatbot as a learning tool in a one-on-one learning environment. The findings showed that ChatBot significantly improved pupils’ academic achievement, particularly in one-on-one situations. It was revealed that the degree to which users perceived ChatBot to be helpful might predict behavioural intent. The study found the usefulness of chatbots for students, as it was strongly influenced by whether or not they would use it in the future. However, it did not investigate how using chatbots influenced certain areas of language learning, such as vocabulary growth and learner independence. The research also did not include a delayed posttest, which limited its ability to comment on long-term retention.

Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) in the AI Era

Boudjedra (2024) explored the views of 50 first-year graduate learners regarding the utilisation of AI to improve SRL. The quasi-experiment consisted of a pretest, a treatment (by employing artificial intelligence (AI) instruments for learning), and a posttest to measure SRL utilizing the motivated strategies for learning survey. The survey’s findings indicated positive views about using AI for learning, and utilising AI increased students’ self-regulation. The advantage of this study lies in its focus on learners’ metacognitive engagement. However, the small population of this study and the lack of measurements for specific outcomes, such as vocabulary acquisition, could be considered limitations of the study.

Ng et al. (2024) investigated the efficacy of an AI helper tool (SRLbot) in promoting SRL and scientific education among 74 secondary students in Hong Kong. The students were assigned to a treatment group using SRLBot (a ChatGPT-enhanced chatbot) and a control group using NemoBot, a rule-based AI chatbot. The results revealed that the treatment group’s self-regulated learning improved more, demonstrating the promise of AI helper tools such as ChatGPT in promoting SRL and scientific understanding. The study’s strength lies in its comparative design, which compares generative and rule-based AI instruments. It also provides quantitative and qualitative findings. In contrast, the focus of the study is on scientific learning and not language acquisition. Additionally, it did not investigate the ways self-regulated learning was connected to specific subjects, such as word learning or effective communication.

Wei (2023) investigated the impact of AI-mediated language teaching on English learning success, L2 inspiration, and self-regulated learning among EFL students. It featured 60 undergraduates split into two groups: the experimental group received AI-mediated education, while the control group received conventional training. The findings demonstrated that the treatment group outperformed the control group in terms of English learning outcomes, L2 motivation, and self-regulated learning techniques. A qualitative examination of interviews with 14 students from the treatment group revealed that the AI platform enhanced engagement, provided tailored educational experiences, inspired learning, and facilitated self-directed learning. Although the study adopts a holistic approach, combining quantitative findings with learners’ narratives to demonstrate the multifaceted advantages of AI instruments, it primarily relies on self-reported measurements, which can lead to bias. Additionally, the study lacked a delayed posttest to assess the sustainability of the results over a longer period. Moreover, the study did not examine the separate language skills, such as vocabulary.

Al Ghaith et al. (2024) examine how employing an AI support tool (a WhatsApp bot) affects Omani EFL students’ acquisition and retention of English terms across three competence levels (elementary, pre-intermediate, and intermediate). One hundred fifty people were randomly chosen and divided into treatment and control groups. A WhatsApp bot was used to teach words to the treatment groups, whereas conventional teacher-led education was used for the control groups. Compared to conventional training, the results showed that an artificial intelligence (AI) support tool (a WhatsApp bot) significantly improved vocabulary acquisition and retention for basic and intermediate students. This study makes a significant impact by combining experimental design with data on user acceptance. This provides information on performance and insights into attitudes. However, it examined vocabulary results, but it did not investigate the broader educational tactics (such as autonomy, engagement, or long-term interaction) that would have facilitated these changes.

Methodology

Participants

The primary demographic of the research was 60 Omani English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners, who were responsible for collecting the necessary data. According to the college’s academic standards, these individuals were classified as having intermediate English proficiency levels. Their native language was Arabic, and they were between 18 and 21 years old. Random selection divided these learners into two groups, with a comparable number of learners in each cohort. A control group that attended regular in-person classes and a treatment group that utilized Copilot to learn the words.

It is worth mentioning that there was no power analysis officially conducted over the number of students in this study. It could be stated that in some applied linguistics and educational technology research studies, the group sizes of 25 to 30 students are stated to be sufficient to detect the effect sizes from medium to large (Plonsky & Oswald, 2014)

Instruments

Vocabulary Test

The investigators created three sets of assessments to track students’ performance before and after the treatment: pretests, posttests, and delayed posttests. Each exam consisted of thirty questions, a mix of multiple-choice and fill-in-the-blank questions. SPSS software version 27.0 was used to measure the three tests. Before the examinations were administered, thirty Omani EFL learners from the same institution piloted the test, and three holders of doctoral degrees in Applied Linguistics approved it. The test reliability is shown in Table 1.

Table 1

The Results of the Reliability Index for All Sets of Tests

Self-Regulated Learning Questionnaire (SRLQ)

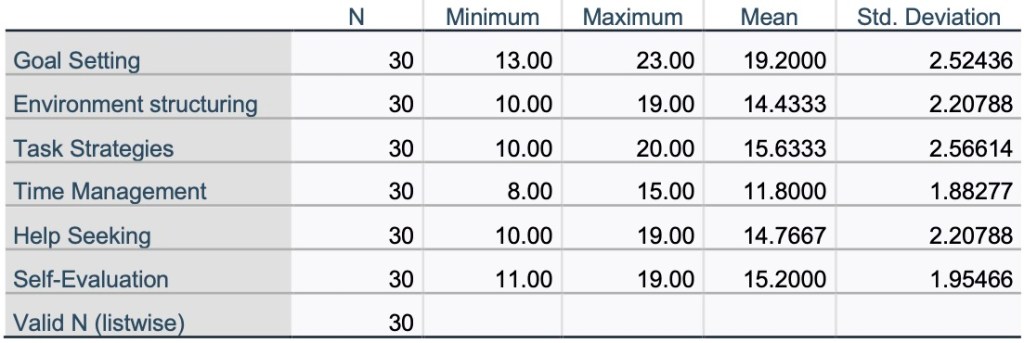

To measure the effect of implementing AI within the learning context and the autonomy of the learners, a 24-item self-regulated learning questionnaire was adapted. This questionnaire, initially developed by Barnard et al. (2009), comprises six subscales: goal setting (5 items), environment structuring (4 items), task strategies (4 items), time management (3 items), help-seeking (4 items), and self-evaluation (4 items). The items were measured using a Likert Scale, with 5 referring to “strongly agree,” 4 to “agree,” 3 meaning “neutral,” 2 referring to “disagree,” and 1 to “strongly disagree.” Since this questionnaire was originally prepared for online and blended learning, some of the statements were adapted to measure the variables of this study more precisely. To ensure the reliability of this survey, a pilot study was conducted with 30 Omani EFL students who had the same English proficiency level as the study’s participants and were from the exact location. Table 2 below presents the results of descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s Alpha for the six categories, which range from 0.733 to 0.837, indicating adequate reliability. Additionally, three Omani PhD holders in Applied Linguistics with more than 10 years of teaching experience reviewed the questions for their suitability in terms of language and context. Before distributing the survey, the Arabic translation of the statements was provided beside the English statements.

Table 2

The Descriptive Analysis and Results of Reliability Index for SRLQ

Copilot via WhatsApp

Copilot was incorporated as an AI assistant that treatment group members could access via WhatsApp, utilising the official WhatsApp Business API. Through an exclusive WhatsApp number, learners may communicate with Copilot and get real-time assistance with vocabulary study. The integration allowed Copilot to handle natural language inquiries, provide examples, define words, and make practice activities. The technology was designed to track previous conversations and provide tailored responses based on how students interacted with it.

Procedure

Following institutional ethical approval and informed consent from all participants, the study was conducted in the first semester of 2025 at a university in Oman. The study duration was 4 weeks. In the first week, using random assignments to ensure group equivalence, the researcher divided students into control and experimental groups. Although both groups participated in regular face-to-face classes, the experimental group used Copilot through WhatsApp to understand the words and the in-class training. Before beginning the treatment, both groups participated in a vocabulary pretest to ensure homogeneity of their knowledge. After that, the researcher conducted a training session for the experimental group on using Copilot through WhatsApp. Students were informed that they would receive 10 words through Microsoft Teams every other day and would need to study them before attending class the following day.

The students used Copilot questions to clarify the meaning of each word in both Arabic and English, and requested examples for each word. They also asked Copilot to design fill-in-the-blank and multiple-choice practice questions and then sent their answers to Copilot for correction. The following day, the researchers checked the students’ Copilot conversations to ensure task completion and consistency. The researchers then discussed the 10 words with the students by asking about word meanings using eliciting techniques.

The same procedure was followed for other word sets as well. Additionally, the researchers assigned homework to be discussed on day 5. The exact process was followed in weeks 2 and 3 for the remaining words, while the control group studied the words using traditional teaching methods. At the end of week 3, students completed a vocabulary posttest and self-regulated learning questionnaire. At the end of week 4, students took a delayed posttest.

Data Analysis

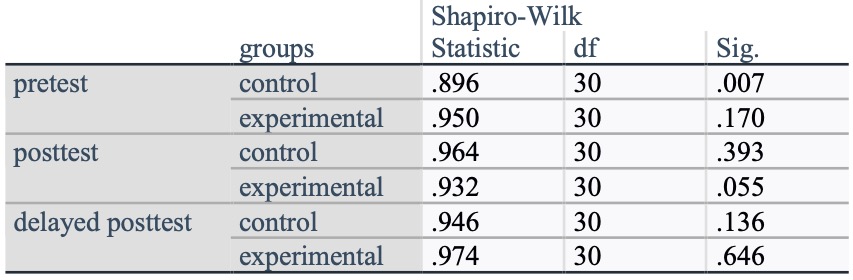

Initially, it was necessary to assess the normality of the data to exclude extreme values and select the appropriate parametric or nonparametric comparison tests. Table 3 below presents the results of the Shapiro-Wilk normality tests conducted across all sets.

Table 3

The Results of Normality Tests in All Data Sets

Table 3 shows that the control group’s pretest does not follow a normal distribution (p = 0.007), whereas the experimental group’s pretest does (p = 0.170). The posttest scores of the control group (p = 0.393) and the experimental group (p = 0.055) met the normality criterion. The control group (p = 0.136) and the experimental group (p = 0.646) showed similar normality in the delayed posttest scores. Therefore, both parametric and nonparametric tests will be conducted to compare the participants’ results within their groups and between groups. Table 4 below presents the descriptive statistics of the tests across both groups.

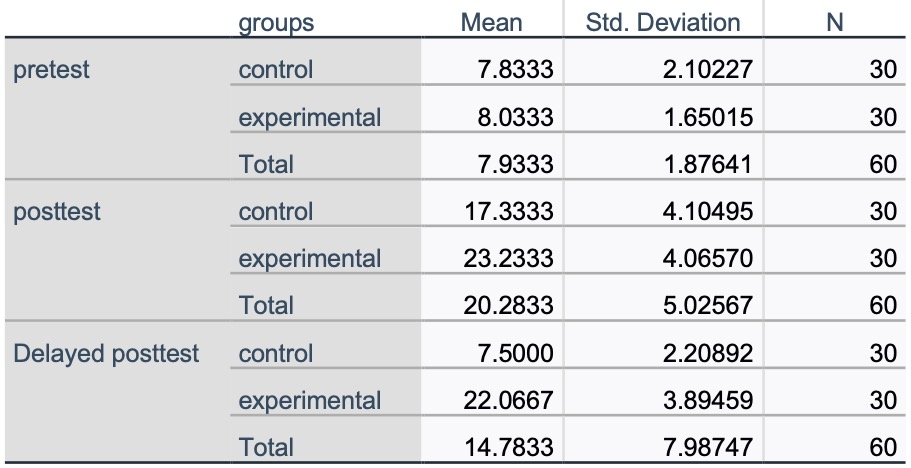

Table 4

The Descriptive Analysis of Pretest, Posttest and Delayed Posttest Across All the Groups

Table 4 shows that during the pretest, the control group (M = 7.83, SD = 2.10) and the experimental group (M = 8.03, SD = 1.65) had similar vocabulary scores. After the treatment period, both groups showed signs of progress, with the experimental group performing better (M = 23.23, SD = 4.07). This could be associated with the use of Copilot on vocabulary acquisition. In the delayed posttest, the control group (M = 7.50, SD = 2.21) showed a dramatic decrease in vocabulary score, while the experimental group performed well (M = 22.07, SD = 3.89). Table 5 below presents the Wilcoxon signed-rank test results for the control group.

Table 5

The Results of Pretest, Posttest, and Delayed Posttest Within the Control Group

Table 5 reveals significant differences (p < 0.0001), indicating substantial improvements in scores from the pretest to the posttest. The comparison of pretest and delayed posttest scores did not reveal any significant differences, with a p-value of 0.666, indicating that the scores could not be maintained over the long term. In addition, the comparison of the posttest and the delayed posttest shows a significant difference in scores between the two sets of tests (p <), indicating a substantial decline in scores in the delayed posttest. The results confirmed the students’ initial progress in the posttest; however, retention of vocabulary knowledge was unsatisfactory. To compare the participants’ results in the experimental group, a parametric test, the Paired-Samples T-Test, was conducted; the results are presented in Table 6 below.

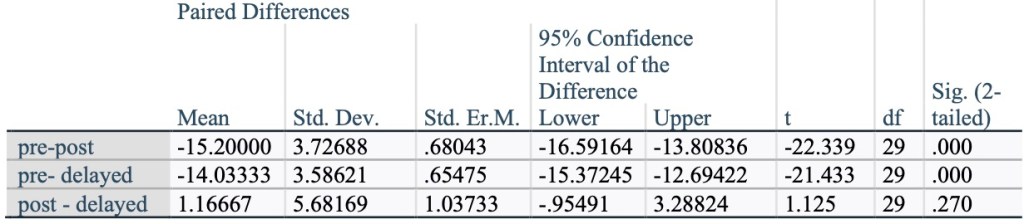

Table 6

The Results of the Pretest, Posttest, and Delayed Posttest Within the Experimental Group

Table 6 reveals that, in both the posttest and delayed posttest, there is a significant positive difference in scores, with a mean improvement of p < 0.001, confirming the performance improvements of participants in the posttest and their maintenance of similar scores in the delayed posttest. Table 7 compares data sets between the control and experimental groups using the Mann-Whitney U Test.

Table 7

The Comparison of Pretest, Posttest, and Delayed Posttest of Control and Experimental Groups

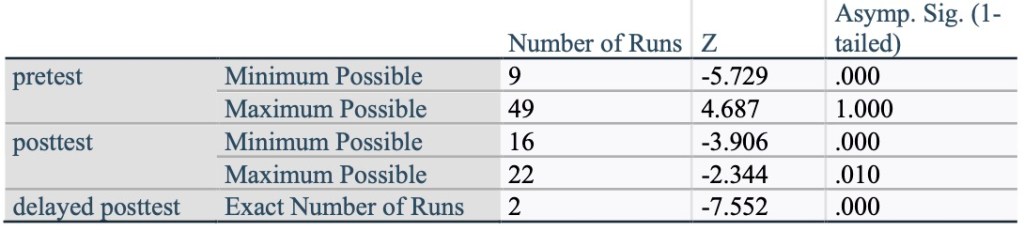

Table 7 shows no significant difference between the two groups in the pretest (p = 0.604). However, comparing the posttests reveals substantial differences between the results of the two groups (p = 0.000). In addition, comparing the delayed posttest reveals the same results as the (p = 0.000). To determine which group performed better in the tests, a Wald-Wolfowitz test was conducted; the results are presented in Table 8 below.

Table 8

The Comparison of the Performance of Both Groups in All Tests

Based on Table 8, the posttest results (p < 0.001 and p = 0.010) showed that the experimental group performed significantly better. The results of the delayed posttest yielded a p-value of less than 0.001, indicating a highly significant difference whereby the experimental group performed better than the control group. Figure 1 below shows the performances of both groups in the pretest, posttest, and the delayed posttest.

Figure 1

The Visual Presentation of Experimental and Control Groups Comparisons in all Three Tests

The second part of this section analyzed the self-regulated learning of the experimental group before and after the treatment. A One-Sample T-test was run to compare students’ performance in the pretest and posttest, and Table 9 below shows the results.

Table 9

The Results of Comparing Self-Regulated Learning Skills in Pretest and Posttest

Table 9 shows that the results of the pretest and posttest indicate a statistically significant mean difference of 58.13 to 74.07, respectively. The results demonstrate a significant improvement in the self-regulated learning skills of the experimental group following the implementation of the treatment. These results indicate significant gains in self-regulated learning between the pretest and posttest. Further analysis was conducted to identify the students’ skills that showed significant improvement. Table 10 below shows the results of descriptive analysis.

Table 10

The Descriptive Analysis of the 24-Item Self-Regulated Learning Questionnaire

Table 10 demonstrates that the Goal Setting (M = 19.20, SD = 2.52), Task Strategies (M = 15.63, SD = 2.57), and Self-Evaluation (M = 15.20, SD = 1.95) components of SRL exhibited the most outstanding mean scores implying that they were improved substantially through the addition of Copilot. The engagement in the domains of Help Seeking (M = 14.77, SD = 2.21) and Environment Structuring (M = 14.43, SD = 2.21) were moderate, whereas the lowest fixation was identified in the Time Management domain with the mean (M = 11.80, SD = 1.88) that indicates that it showed the least changes during the intervention. These results suggest that Copilot was the most effective in terms of cognitive and metacognitive activities, such as planning and strategy implementation, or reflective thinking, which are key to autonomous learning.

Discussion

The current study attempted to investigate the impact of using Copilot as a facilitator in vocabulary learning. In addition, the study measured the effect of this tool on the students’ SRL skills. For this purpose, 60 Omani students with intermediate English proficiency were divided into two equal groups: an experimental group and a control group. During the 4 weeks of training, both groups received similar materials, training, and instructions from the teachers; however, the experimental group was instructed and guided to use Copilot as an extra facilitator in the learning process. Researcher-made pretests, posttests, and delayed posttests were conducted, and it was determined that both groups showed progress in learning vocabulary in the posttest; however, the experimental group’s progress was remarkably greater. In the delayed posttest, the control group showed no signs of progress, and their marks decreased compared to the initial posttest. Concurrently, the experimental group showed significant improvement in vocabulary retention. This could lead the study to conclude that combining learning context with Copilot can positively influence learners’ skills in a language learning context.

The control group’s posttest results are supposed to indicate how well conventional instructional techniques facilitate immediate vocabulary acquisition for learners. However, it was revealed that conventional methods, which focus on rote memorisation rather than active cognitive involvement, lead to a lack of retention.

The significant improvement of the experimental group on the posttest and delayed posttest can be attributed to the unique advantages offered by Copilot. Copilot allegedly provided customised support using adaptive learning methods, responding to each student’s individual needs and augmenting their understanding and recall. Furthermore, the software’s interactive features are likely to increase motivation and interest, thereby facilitating students’ active engagement in learning activities. The real-time feedback that Copilot enables likely encourages learners to rehearse and review words on a daily basis, thereby improving long-term memory retrieval. In addition, the artificial intelligence system likely facilitated self-regulated learning by giving students control over their learning process, thereby fostering metacognitive strategies, including planning, monitoring, and evaluating their learning, which is essential for long-term success.

The results of the study could be associated with some of the active theories in this area, such as Self-Regulated Learning (Zimmerman, 2002), in which the use of Copilot seems to facilitate the cycle of forethought, performance, and self-reflection by helping learners plan, engage, and evaluate their progress. This leads to improvements in metacognitive awareness, which is the basis of autonomous learning. Additionally, Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985) is connected to the findings of this study, which emphasise autonomy, competence, and intrinsic motivation.

The results of the study on vocabulary improvement and AI tools align with Selvi’s (2024), who integrated AI technologies into English vocabulary acquisition by comparing various platforms and discovered that AI can increase vocabulary acquisition and retention through repetition, personalised learning, and immediate feedback. Similarly, Kazu and Kuvvetli (2023) investigated whether artificial intelligence-supported instruction improves vocabulary retention among English language learners and found that artificial intelligence significantly enhanced learners’ vocabulary acquisition and retention. In another study with similar results, Aldowsari and Aljebreen (2024) examined the impact of a ChatGPT-based application on vocabulary acquisition among Saudi learners and found that the treatment group performed significantly better in terms of vocabulary acquisition and retention.

The SRL finding of this study aligns with Rahim et al. (2024), who investigated the feasibility of employing ChatGPT to enhance learners’ SRL capacities in the context of scientific education, and found that intelligent technology has tremendous potential to help learners develop SRL skills. Similarly, Sardi et al. (2025) investigated how generative intelligent technology (AI), especially tools such as ChatGPT, affects learners’ self-regulated learning (SRL) and critical thinking abilities. The research found that artificial intelligence improves self-regulated learning, primarily through individualised learning, metacognitive assistance, and responsive feedback. Chang and Sun (2024) investigated the effectiveness of artificially intelligent (AI) technologies in promoting self-regulated language acquisition. The study demonstrated that AI technologies significantly enhance students’ self-regulated learning processes.

Conclusion

This study aimed to investigate two objectives. The first goal was to measure the impact of using Copilot on the vocabulary knowledge of EFL students, and the secondary goal was to monitor the self-regulated learning skills among the experimental group participants. The study’s findings revealed that the experimental groups exposed to Copilot as a learning facilitator performed significantly better on the vocabulary posttest and delayed posttest. In addition, self-regulated skills increased among them in comparison to the beginning of the study. All these factors could support the conclusion that using AI tools, such as Copilot in this context, can be helpful in the language learning process.

The findings of this research have important implications for students, instructors, and institutions. Teachers can utilise Copilot to make conventional approaches more efficient, develop richer and more engaging curricula, and enable autonomous learning. With AI-facilitated feedback and adaptive capabilities, instructors can tailor their responses to individual students’ needs and enhance overall class effectiveness. Students can build vocabulary in a short period and develop steadily, with a strong foundation for mastering the language. Institutions can greatly benefit from this research, as it informs them about AI in current education and the value of investing in technology-enabling experiences within their institution.

One of the drawbacks of the present study is its relatively small sample size, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to larger populations. This drawback may be overcome in future studies by having a more diverse and larger group of participants to cross-validate and generalize the findings. The scope of the present study was limited to intermediate Omani EFL learners. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings is limited to learners with different proficiency levels or from diverse cultural backgrounds. Subsequent research can investigate the effect of artificial intelligence software on learning vocabulary among students of different proficiency levels and in various cultural and linguistic contexts.

The experiment was conducted over a four-week training period, which may not be representative of the long-term effects of applying AI technologies, such as Copilot, on language memory and independent learning ability. Long-term longitudinal studies are recommended to investigate the effects of sustained AI tool use on long-term language learning outcomes.

Another limitation of the study is its focus on vocabulary development only, which may not fully represent the potential of AI tools to improve other language skills, such as speaking, writing, listening, and grammar. Future research can explore the use of AI approaches in developing overall language competence by incorporating other skills into the study. Moreover, analysing the extent to which artificial intelligence applications integrate with various teaching approaches, such as collaborative learning and project-based work, may better establish their impact.

The study did not examine the significant degree to which certain Copilot features, such as adaptive feedback and immediate correction of mistakes, affected reported measures. Subsequent research can concentrate on feature-by-feature comparisons to understand what aspects of artificial intelligence tools have the most significant impact on language acquisition and memory enhancement. Such an undertaking can help create AI tools and optimise their teaching potential. Subsequent research can also investigate the interplay between learner characteristics, motivation, technical proficiency, learning style, and AI-enhanced learning to facilitate the tailoring of learning strategies.

Notes on the Contributors

Dr. Behnam Behforouz is an English Lecturer in the Preparatory Studies Center at the University of Technology and Applied Sciences, Shinas, Oman. He has been teaching English at various Omani universities since 2015. His main areas of interest include TESOL and educational technologies.

Ali Al Ghaithi is an English Lecturer in the Foundation Department of Sohar University in Oman. He is currently a Ph.D. candidate focusing on Applied Linguistics. Ali got his master’s degree from the University of Putra Malaysia. He began his career as an English Lecturer in 2018. Ali is interested in research studies that mainly implement Artificial Intelligence in teaching and learning processes.

References

Al Ghaithi, A., Behforouz, B., & Isyaku, H. (2024). The effect of using WhatsApp bot on English vocabulary learning. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 25(2), 208–227. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.1297285

Aldowsari, B. I., & Aljebreen, S. G. (2024). The Impact of using a ChatGPT-based application to enhance Saudi students’ EFL vocabulary learning. International Journal of Language and Literary Studies, 6(4), 380–397. https://doi.org/10.36892/ijlls.v6i4.1955

Ateeq, A., Alaghbari, M. A., Alzoraiki, M., Milhem, M., & Beshr, B. A. H. (2024). Empowering academic success: Integrating AI tools in university teaching for enhanced assignment and thesis guidance. 2024 ASU International Conference in Emerging Technologies for Sustainability and Intelligent Systems (ICETSIS), 297–301. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICETSIS61505.2024.10459686

Barnard, L., Lan, W. Y., To, Y. M., Paton, V. O., & Lai, S.-L. (2009). Measuring self-regulation in online and blended learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 12(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.10.005

Bensalem, E. (2018). The impact of WhatsApp on EFL students’ vocabulary learning. Arab World English Journal, 9(1), 23-38. https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol9no1.2

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and Researching Autonomy in Language Learning (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Boudjedra, A. (2024). Promoting EFL learners’ Self-regulated Learning through the Use of Artificial Intelligence Applications [Master’s thesis, University of Guelma]. https://dspace.univ-guelma.dz/jspui/handle/123456789/16767

Chang, W.-L., & Sun, J. C.-Y. (2024). Evaluating AI’s impact on self-regulated language learning: A systematic review. System, 126, 103484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2024.103484

Chen, Z., Jia, J., & Li, W. (2021). Learning curriculum vocabulary through mobile learning: Impact on vocabulary gains and automaticity. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation, 15(2), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMLO.2021.114518

Chen, H.-L., Vicki Widarso, G., & Sutrisno, H. (2020). A chatbot for learning Chinese: Learning achievement and technology acceptance. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 58(6), 1161–1189.

Chiu, T. K. F. (2024). A classification tool to foster self-regulated learning with generative artificial intelligence by applying self-determination theory: A case of ChatGPT. Educational Technology Research and Development, 72(4), 2401–2416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-024-10366-w

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

Diwan, C., Srinivasa, S., Suri, G., Agarwal, S., & Ram, P. (2023). AI-based learning content generation and learning pathway augmentation to increase learner engagement. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 4, 100110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100110

Gibson, C. (2016). Bridging English language learner achievement gaps through eEffective vocabulary development strategies. English Language Teaching, 9(9), 134–138. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v9n9p134

Hashemifardnia, A., Namaziandost, E., & Rahimi Esfahani, F. (2018). The effect of using WhatsApp on Iranian EFL learners’ vocabulary learning. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research, 5(3), 256–267.

Hwang, G.-J., Xie, H., Wah, B. W., & Gašević, D. (2020). Vision, challenges, roles and research issues of Artificial Intelligence in education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 1, 100001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2020.100001

Jia, F., Sun, D., Ma, Q., & Looi, C. K. (2022). Developing an AI-based learning system for L2 learners’ authentic and ubiquitous learning in English language. Sustainability, 14(23), 15527. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315527

Kazu, I. Y., & Kuvvetli, M. (2023). The influence of pronunciation education via Artificial Intelligence technology on vocabulary acquisition in learning English. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies, 10(2), 480–493. https://dx.doi.org/10.52380/ijpes.2023.10.2.1044

Markauskaite, L., Marrone, R., Poquet, O., Knight, S., Martinez-Maldonado, R., Howard, S., Tondeur, J., De Laat, M., Shum, S. B., & Gašević, D. (2022). Rethinking the entwinement between artificial intelligence and human learning: What capabilities do learners need for a world with AI? Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3, 100056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100056

Mercer, S., & Dörnyei, Z. (2020). Engaging language learners in contemporary classrooms. Cambridge University Press.

Ng, D. T. K., Tan, C. W., & Leung, J. K. L. (2024). Empowering student self‐regulated learning and science education through ChatGPT: A pioneering pilot study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 55(4), 1328–1353. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13454

Plonsky, L., & Oswald, F. L. (2014). How big is “big”? Interpreting effect sizes in L2 research. Language Learning, 64(4), 878–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12079

Rad, H. S., Alipour, R., & Jafarpour, A. (2023). Using artificial intelligence to foster students’ writing feedback literacy, engagement, and outcome: A case of Wordtune application. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(9), 5020–5040. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2208170

Rahim, F. R., Widodo, A., Samsudin, A., & Dahlan, T. H. (2024). Enhancing self-regulated learning with ChatGPT: A study in science education. Proceeding of the International Conference on Mathematical Sciences, Natural Sciences, and Computing, 1(2), 35–48. https://prosiding.arimsi.or.id/index.php/ICMSNSC/article/view/21

Sardi, J., Darmansyah, Candra, O., Yuliana, D., Habibullah, Yanto, D., & Eliza, F. (2025). How generative AI influences students’ self-regulated learning and critical thinking skills? A systematic review. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy (iJEP), 15, 94–108. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijep.v15i1.53379

Selvi, V. T. (2024). Applications and analyzes of Artificial Intelligence in enhancing English vocabulary. Recent Research Reviews Journal, 3(2), 333–345. https://doi.org/10.36548/rrrj.2024.2.002

Shadiev, R., Wu, T.-T., & Huang, Y.-M. (2020). Using image-to-text recognition technology to facilitate vocabulary acquisition in authentic contexts. ReCALL, 32(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344020000038

Sivabalan, K., & Ali, Z. (2022). The effectiveness of WhatsApp in vocabulary learning. Innovative Teaching and Learning Journal, 6(2), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.11113/itlj.v6.82

Tu, Y., Zou, D., & Zhang, R. (2020). A comprehensive framework for designing and evaluating vocabulary learning apps from multiple perspectives. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation, 14(3), 370. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMLO.2020.108199

Wang, Y., & Xue, L. (2024). Using AI-driven chatbots to foster Chinese EFL students’ academic engagement: An intervention study. Computers in Human Behavior, 159, 108353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108353

Wei, L. (2023). Artificial intelligence in language instruction: Impact on English learning achievement, L2 motivation, and self-regulated learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 01–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1261955

Xia, Q., Chiu, T. K. F., & Chai, C. S. (2023). The moderating effects of gender and need satisfaction on self-regulated learning through Artificial Intelligence (AI). Education and Information Technologies, 28(7), 8691–8713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11547-x

Yang, H. J., & Kim, H. Y. (2021). Development and application of AI chatbot for cabin crews. Korean Journal of English Language and Literature, 21, 1085–1104. https://doi.org/10.15738/kjell.21..202110.1085

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2