Ruba Fahmi Bataineh, Yarmouk University, Jordan. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5454-2206

Enas Naim Al-Ghoul, Ministry of Education, Jordan. https://orcid.org/0009-0007-0275-8674

Rula Fahmi Bataineh, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Jordan. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4982-7338

Bataineh, R. F., Al-Ghoul, E. N., & Bataineh, R. F. (2025). Backed against a Wall: The potential utility of self-regulated online reading instruction. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(1), 25–59). https://doi.org/10.37237/202407

Published online first: 14 December 2024

Abstract

During the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, Jordan enforced a nationwide lockdown. In an attempt to sustain education, the Ministry of Education immediately transitioned to online instruction through Darsak (Arabic for Your Lesson) platform to provide free of charge daily Arabic, English, physics, mathematics, computer science, history, and financial literacy lessons to public school first- through twelfth-grade students in the country. To determine the potential effect of self-regulated learning in online instruction on Jordanian EFL students’ reading comprehension, a quasi-experimental design was used with a sample of three ninth-grade sections from a purposefully selected all-girl school in Amman, Jordan. The three sections were randomly distributed into two experimental groups taught online, one through Darsak II (the official Ministry of Education platform) and the other through Facebook, and one control group taught per the guidelines of the prescribed teacher’s book. A 10-week, two-tiered instructional program was designed, validated, and then implemented to the experimental groups whereas the control group received conventional face-to-face instruction. The participants’ reading comprehension was tested before and after the treatment across the three groups. Not only was online instruction found to boost overall reading comprehension, but it was found to positively affect specific reading skills such as scanning and inferencing, more so than conventional face-to-face instruction. Furthermore, no statistically significant differences were found in reading comprehension between the participants of the two experimental groups. This research provides preliminary evidence for the utility of online instruction for self-regulated learning of reading comprehension, which goes beyond times of crisis into normal everyday schooling.

Keywords: Darsak Platforms; Facebook; inferencing; Jordan; online instruction; reading; scanning; self-regulated learning

Following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, a nationwide lockdown was announced throughout Jordan. The Jordanian Ministry of Education (MoE) put forth a rapid response plan, dubbed Education during Emergency Plan, to combat the disruption of formal education resulting from the defense orders issued by the Prime Ministry to close schools and universities in an attempt to contain the spread of COVID-19 (MoE, 2020). The plan culminated in the provision of online education to over two million students in public, private, and United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) schools to both instill a sense of normality and prevent the risk of attrition (Batshon & Shahzadeh, 2020).

In response to the educational disruptions caused by the pandemic, the MoE launched an online educational platform, Darsak (Arabic for Your Lesson), to support remote learning (MoE, 2020). The initial version of the platform was launched in March 2020 to provide access to educational content during the early stages of the pandemic. Made accessible to all students in Jordan, it offered pre-recorded lessons across various subjects to grades 1 through 12 to help students continue their education during school closures.

Considering teacher feedback and evolving students’ needs, Darsak II, an updated version of the original platform, was later introduced with more interactive features, additional resources, and an improved user interface. It constituted a critical tool for distance learning, with a host of video lessons, quizzes, and supplementary resources aligned with Jordanian curricula. Throughout this study, Darsak is used to refer to Darsak II since the former is the common name used in literature, and the number is just a matter of showing that the portal has an updated version.

Problem, Purpose, and Scope of the Research

The researchers, all experienced ELT practitioners, have observed first-hand the difficulties the majority of Jordanian EFL learners face in reading in general and reading comprehension in particular. Teachers and parents alike felt that difficulties have been compounded with the disruption of formal face-to-face education in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and resorting to asynchronous online instruction for almost two years.

This study examines the potential effect of self-regulated learning in online instruction on Jordanian female EFL ninth-grade students’ scanning and inferencing skills, as learners, characterized by strong self-regulated learning skills (viz., planning, managing and controlling their learning), are reported to learn faster and better than those with poor or no self-regulated learning skills (Kizilcec et al., 2017). More specifically, the study seeks to answer the question: To what extent does self-regulated learning in online instruction affect Jordanian female EFL learners’ reading comprehension skills of scanning and inferencing?

Scanning and inferencing are examined because a content analysis of the reading content of Modules 5 and 6 of the MoE-prescribed textbook, Action Pack 9, revealed that these are the skills to be emphasized most. The first four modules of the book emphasize other subskills (viz., identifying the main idea, skimming, predicting) which are excluded from the scope of the current research.

Literature Review

Online vs Face-to-Face Language Learning

The relative utility of face-to-face and online instruction is a matter of controversy, as the literature on the issue is divided as to which has more merit. The literature provides evidence that face-to-face instruction is superior to online instruction (Helms, 2014; Johnson & Palmer, 2014). Face-to-face instruction is reported to reduce distractions, encourage active participation, and maintain discipline and focus (Xu & Jaggars, 2013). This, in turn, is advantageous for understanding, higher academic achievement, better communication skills (Johnson & Johnson, 2009), engagement, and retention (Ali & Leeds, 2009; Barnard et al., 2009; Bi et al., 2023; Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005; Xu & Jaggars, 2013). Face-to-face instruction further promotes social interaction and community building among students (Lee, 2024), as group discussions, peer-to-peer learning, and collaborative projects potentially foster a sense of belonging and shared purpose.

However, a plethora of research seems to suggest that online instruction is either as effective as traditional face-to-face instruction (e.g., Bataineh & Bataineh, 2024; Bataineh et al., 2020; Harmon & Lambrinos, 2006; Means et al., 2010; Navarro & Shoemaker, 2000; Nguyen, 2015; Zidat & Djoudi, 2010) or more so in language education (e.g., Al-Musili et al., 2022). For example, in their meta-analysis of 51 experimental and quasi-experimental studies on online learning between 1996 and 2008, Means et al. (2010) reported that, on average, students in online learning conditions outperform those receiving face-to-face instruction. 97 percent of the research they reviewed reported on the relative effectiveness of online learning as opposed to only 3 percent that reported the opposite.

Self-Regulated Learning

Self-regulated learning is a dynamic process by which learners independently initiate, maintain, and strategically direct thoughts, emotions, and actions towards achieving certain goals (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2011). A critical skill for effective learning and personal development, self-regulated learning is positively correlated with academic performance (Richardson et al., 2012; Schneider & Preckel, 2017; Schunk & Zimmerman, 2007). In other words, self-regulated learning involves setting realistic goals, using effective study strategies, and persevering in the face of challenges, which requires learners to engage in the following processes (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2007; Zimmerman, 2000, 2002):

- self-observation, or monitoring one’s own performance and behavior,

- self-judgment, or benchmarking one’s performance against a pre-set goal,

- self-instruction, or adjusting one’s performance to improve future outcomes, and

- self-reinforcement or rewarding oneself for achieving goals.

A plethora of empirical evidence attests to the effectiveness of self-regulated learning in academic achievement (e.g., Cleary & Platten, 2013; Dent & Koenka, 2016; McCombs, 2013; Xu et al., 2023; Zheng, 2016; Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994; Zimmerman & Martinez-Pons, 1988), motivation to learn (e.g., Daniela, 2015; Kizilcec et al., 2017; Miele & Scholer, 2016; Sansone et al., 2011), autonomy (e.g., de Fátima Goulão & Menedez, 2015; Lashari et al., 2021; Lewis & Vialleton, 2011; Loyens et al., 2008; Murray, 2014; Nakata, 2014), and lifelong learning (e.g., Öz & Şen, 2021; Skinner et al., 2015; Taranto & Buchanan, 2020). However, research reports that many students suffer from poor self-regulation of their learning (Peverly et al., 2003), manifested in poor learning strategies (Bjork et al., 2013), poor time management (Steel, 2007), and, eventually, poor academic performance (e.g., Dignath et al., 2008), which makes it imperative to help learners develop their self-regulated learning skills.

Self-regulated learning is crucial not only for helping students attain high academic performance but also for achieving their learning objectives in the online learning context (Jin et al., 2023). Identifying self-regulated learning strategies correlated with academic excellence is critical for the effective design and implementation of online reading instruction. Furthermore, making use of interactive platforms (viz., those that support interactive and adaptive learning) is also instrumental in promoting self-regulated learning. Interactive platforms not only personalize feedback and interventions but also goal-setting modules, progress tracking dashboards, and reflective prompts to facilitate self-regulated learning (e.g., Delen & Liew, 2016; Jin et al., 2023; Molenaar et al., 2019).

Self-Regulated Learning and Online Language Learning

Online education has become a defining feature of the twenty-first century, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Hodges et al., 2020; Watson & Johnson, 2011). This shift has underscored the importance of learner autonomy, engagement, and motivation in fostering self-regulated learning (e.g., Ha, 2023). Self-regulated learning, which refers to the goal-driven process of acquiring knowledge and skills, involves the learner’s ability to manage the factors influencing his/her own learning over time. Essential to this process are age-appropriate strategies for planning, monitoring, and evaluating learning, as well as practices in self-evaluation and self-reflection (Benson, 2011; Dembo & Eaton, 2000; Dembo et al., 2006; Miller & Brickman, 2004; Vansteenkiste et al., 2012; Winne, 1995).

As online instruction, whether fully online or blended, becomes increasingly common across K-12, tertiary, and higher education, it demands greater self-regulation from students. Unlike face-to-face settings, where teachers are readily available to help students manage their learning, online learning environments are often characterized by high learner autonomy and minimal teacher presence (Jansen et al., 2020). Consequently, students must rely on self-regulated learning to achieve academic success in these settings (Kizilcec et al., 2017).

Research suggests that social networking can significantly improve language learning by offering learners opportunities for both self-directed study and authentic interaction in a real-world, albeit virtual, environment—rather than in artificial scenarios designed solely for classroom use (Ekoc, 2014; Juang, 2010; Simpson, 2011; Zarei & Amani, 2018). Facebook has been recognized as an effective platform for teaching and learning languages (Aydin, 2012; Barrot, 2018; Blattner & Fiori, 2009; Ekoc, 2014; Faryadi, 2017; Kabilan et al., 2010). For example, Faryadi (2017) reported that, compared to traditional methods, using Facebook in foreign language learning led to notable improvements in proficiency, comprehension, motivation, satisfaction, and overall test scores.

Flexibility is one of the key advantages of online learning, which allows learners to study at their own pace and time without needing the teacher’s simultaneous presence—an option not typically available in face-to-face learning (Lee, 2024). Online learning and self-regulated learning are highly compatible (Mulling & Watkins, 2022; Wang, 2023; Yang & Kim, 2014), as online platforms provide the tools, resources, and environment that foster self-regulation. Through online learning, students develop essential skills such as autonomy, personalization, and ownership, which empower them to take charge of their education and create personalized learning experiences tailored to their unique needs and preferences (Choi et al., 2018; Koksal & Dundar, 2018).

In brief, online learning can both facilitate and encourage learners to engage in self-regulated learning (Carneiro et al., 2011; Hannafin & Hannafin, 2010) without relying on the teacher or any other agents of instruction (Istifci & Goksel, 2022). This is especially important in foreign language contexts in which language input and opportunities for active use of the target language are scarce and infrequent (Choi et al., 2018).

Self-Regulated Learning in Reading

Self-regulated learning has been extensively researched in the context of EFL reading, revealing significant effects on learners’ ability to process and understand texts. The literature suggests that self-regulated learning has positive effects on reading comprehension, through fostering metacognitive awareness, motivation, and transfer of reading skills (e.g., Aghaie & Zhang, 2012; Dent & Koenka, 2016; Dörnyei & Csizér, 2012; Magno, 2010; Mokhtari & Reichard, 2002; Oxford, 2016; Pintrich, 2004; Tseng et al., 2006). In their meta-analysis, Dent and Koenka (2016) synthesized evidence on the positive relationship between self-regulated learning and better outcomes in EFL reading comprehension regardless of proficiency levels or cultural backgrounds. Teng and Zhang (2018) also reported that self-regulated learning fostered higher levels of comprehension and improved understanding of complex texts among Chinese EFL learners. Similarly, Oxford (2016) reported on the facilitating role of self-regulated learning in processing, comprehending, and retaining reading materials.

Self-regulated learning has been reported to boost motivation for reading in a foreign language. Pintrich (2004), for example, concluded that self-regulated learners were more motivated to achieve reading goals. Similarly, Wang and Bai (2017) found that self-regulated EFL learners demonstrated better reading comprehension, lower levels of reading anxiety, and higher confidence in their reading abilities.

Self-regulated learning has also been reported to facilitate the transfer of reading skills across various texts and contexts. For example, Mokhtari and Reichard (2002) found that self-regulated EFL learners demonstrated adaptability and better ability to apply reading skills to various text genres, which is essential in EFL contexts, where learners need to possess strategic reading practices to become more flexible and resourceful readers. Dörnyei and Csizér (2012) found that self-regulated learning strategies not only improved reading comprehension but also fostered a deeper engagement with the text. Similarly, Magno (2010) reported that Filipino EFL learners, who used self-regulated learning strategies, outperformed their peers in reading comprehension tasks. Rasekh and Ranjbary (2003) and Aghaie and Zhang (2012) also reported significant improvement in Iranian EFL learners’ reading comprehension due to explicit instruction in self-regulated learning strategies.

Methods

Design, Participants, and Instrumentation

This study used a quasi-experimental design. The participants were students from three ninth-grade sections. They were purposefully selected from Asia Secondary School for Girls in Al-Qweismeh Directorate of Education in Amman, Jordan, at which the second researcher is a teacher. The three sections were then randomly distributed into one control and two experimental groups, taught face-to-face per the guidelines of the prescribed teacher book of Action Pack 9 (n=37), online through Darsak platform (n=39), and online through a closed Facebook group (n=39), respectively (for sample lesson plans and integrated worksheets, see Appendices A-D). The independent variable is the instructional modality while the dependent variables are the reading comprehension skills of scanning and inferencing.

A 20-item multiple-choice reading comprehension test was designed to assess the subskills of scanning and inferencing per specifications based on an analysis of the reading content of Modules 5 and 6 of Action Pack 9. The same test was used immediately before and after the treatment. The validity of the test was established by a jury of ten university professors and one supervisor who assessed its appropriateness of content, wording, and timing. The jury’s feedback was used to produce the final version of the test. The reliability of the test was also established by piloting it to a sample of 30 students who were later excluded from the main sample. The reliability coefficients of 0.88, 0.86, and 0.91for scanning, inferencing, and overall reading comprehension, respectively, were deemed appropriate for the purpose of the research.

To test the equivalence of the three groups of the study in the reading comprehension skills of scanning and inferencing, one-way ANOVA was used to identify potential differences between the three groups. The difference between the performance of the three groups in scanning and inferencing on the pre-test was not statistically significant (α = 0.55 and 0.14, respectively), and, as such, the three groups were deemed equivalent before the treatment.

Instructing the Three Groups

A ten-week instructional program, designed to support self-regulated learning in an asynchronous online setting, was implemented with the two experimental groups (for sample lesson plans and integrated worksheets, see Appendices A-D). At the beginning of the program, the teacher (also the second researcher) introduced strategies to foster independence, self-reflection, and self-monitoring. These strategies aimed to help participants develop essential skills such as planning, time management, and reflective practices.

Not only did the teacher explain what self-regulated learning is and why it is important, but she also provided participants with videos to demonstrate how to apply self-regulated learning skills (viz., setting goals, managing time, monitoring progress, adjusting strategies) in their own learning. She taught them how to set short-term and long-term learning goals through exercises which involved planning ahead to achieve content mastery, skill development, or task completion. She also taught them strategies for effective time management (e.g., creating timelines for completing tasks), regular study, and avoiding procrastination.

The participants in both groups were also provided with regular quizzes and reflective prompts to help them assess their progress, identify challenges, and adjust their approach to learning. They were further taught how to break down complex tasks into smaller, more manageable ones, gradually developing more independence and less reliance on the teacher. They also made use of the discussion forums, in both Darsak and Facebook, to share strategies for managing time, staying on-task, and overcoming challenges as the teacher moderated the discussions and provided feedback to support self-regulated learning behaviors (e.g., persistence, critical thinking, adaptability).

The control group, on the other hand, was taught per the guidelines of the prescribed teacher’s book of Action Pack 9. The teacher first asked the students to talk about the picture accompanying the text then read the title of the passage aloud. The students were then asked to read the text silently to answer comprehension questions, and the teacher provided feedback. The students then read the text silently once more to answer the comprehension questions below it under the watchful eye of the teacher who was on hand for assistance and feedback.

Findings

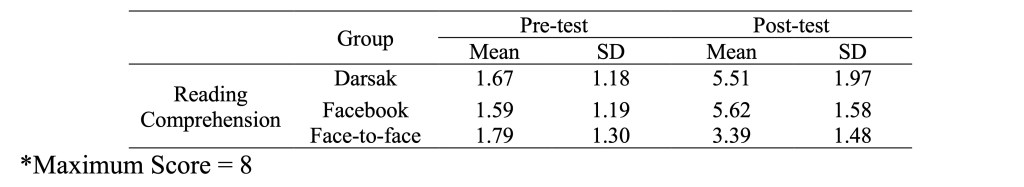

Self-regulation is a key process that affects students’ learning and subsequent academic achievement. To determine the potential effect of online instruction on the participants’ self-regulated learning of reading comprehension, the means and standard deviations of the three groups’ pre-/post-test scores in overall reading comprehension were calculated, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Means and Standard Deviation of the Overall Reading Comprehension on the Pre-/ Post-Test

Table 1 shows observed differences among the mean scores of the three groups’ post-test scores in overall reading comprehension, with higher mean scores for the two experimental groups than the control group and for Facebook than Darsak. One-way Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was used to examine whether or not these observed differences brought about by the instructional modality in overall reading comprehension were statistically significant after controlling the effect of the pre-test, as shown in Table 2.

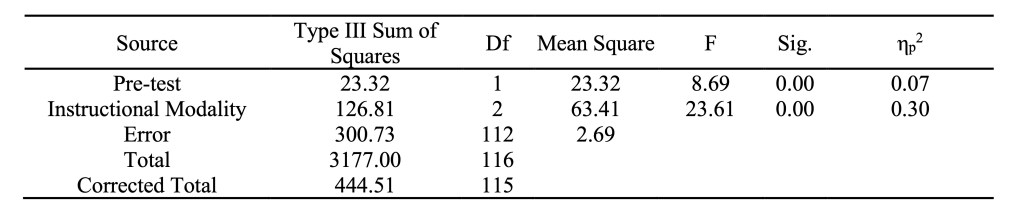

Table 2

One-Way ANCOVA of the Effect of Instructional Modality on Overall Reading Comprehension after Controlling the Effect of the Pre-Test

Table 2 shows that the differences in overall reading comprehension among the participants of the three groups are statistically significant. The partial eta squared value of 0.30 indicates that the instructional modality explained 30 percent of the variance in overall reading comprehension.

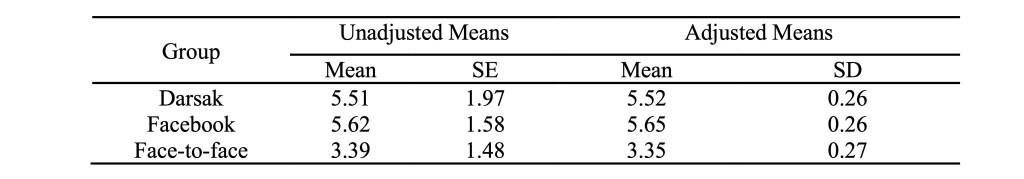

The adjusted and unadjusted means of overall reading comprehension were also calculated for the three groups. Table 3 shows the means, standard errors, and standard deviations of the three groups’ overall reading comprehension before and after controlling the effect of the pre-test.

Table 3

Adjusted and Unadjusted Means of Overall Reading Comprehension per Instructional Modality (with Pre-Test Scores as Covariate)

Table 3 shows observed differences in overall reading comprehension across the three groups (after controlling the pre-test scores). To test the potential significance of these differences, Bonferroni test was used to examine multiple comparisons, as shown in Table 4.

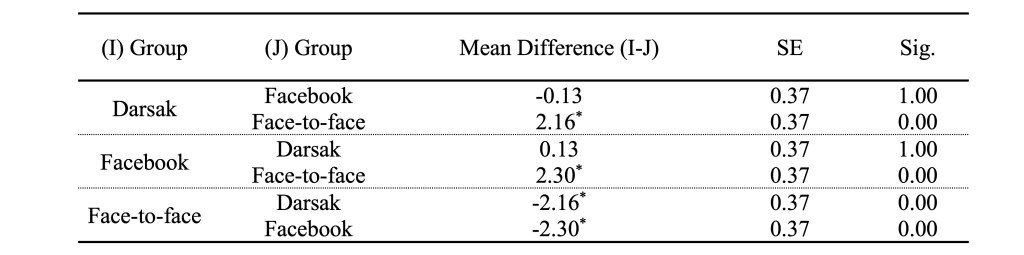

Table 4

Pairwise Differences in Overall Reading Comprehension across Groups

Table 4 shows that the overall reading comprehension mean scores of the Darsak and Facebook groups are significantly higher than that of the face-to-face group. However, no statistically significant differences in overall reading comprehension are found between the two experimental groups.

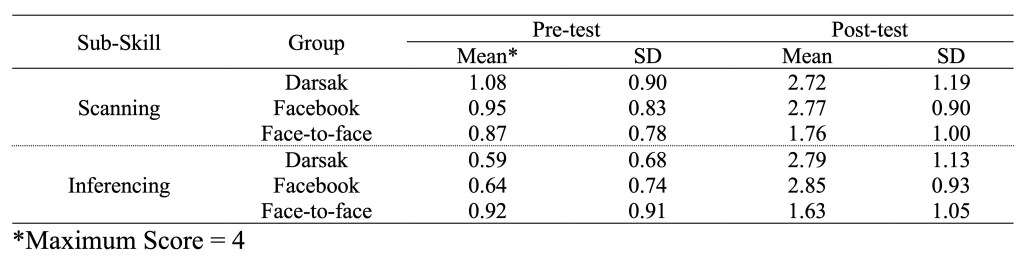

To determine whether or not there are potential differences in the groups’ reading comprehension sub-skills of scanning and inferencing, the means and standard deviations of the students’ respective performance on the pre- and post-test were calculated, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5

Means and Standard Deviations of the Reading Comprehension Sub-Skills on the Pre-/Post-Test

Table 5 shows observed differences in the mean scores of the three groups’ post-test performance in the sub-skills of scanning and inferencing, as the two experimental groups seem to outperform the control group in the sub-skills of reading comprehension. However, the Facebook group seems to outperform the Darsak experimental group in both sub-skills.

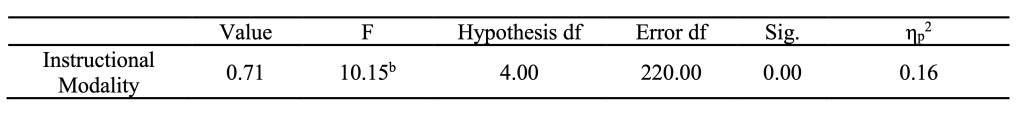

To examine the potential significance of the effect of instructional modality (viz., Darsak, Facebook, and face-to-face) on the linear combination of the reading comprehension sub-skills after controlling the effects of the pre-test scores, a One-Way Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) using Wilks’ Lambda multivariate test was used, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6

Wilks’ Lambda Multivariate Test of the Effect of Instructional Modality

Table 6 shows a significant main effect for the instructional modality (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.71, f(4, 220) = 10.15, p<.0.001, multivariate eta square= 0.16), which suggests that the linear composite of the reading comprehension sub-skills differs across the three groups. The partial eta square value of 0.16 indicates that 16% of the variance in the composite reading comprehension sub-skills may be attributed to the instructional modality. Since the effect of the instructional modality on the combination of the reading comprehension sub-skills is significant, follow-up univariate analysis (between-subjects effects) was performed, as shown in Table 7.

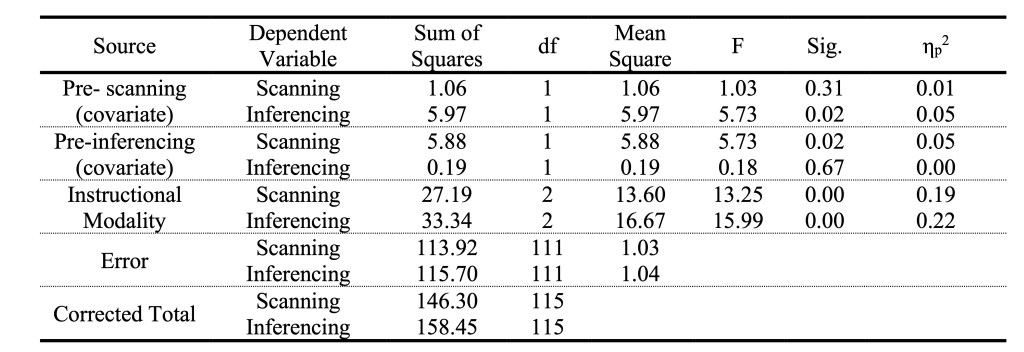

Table 7

Effect of the Instructional Modality on the Sub-Skills (after Controlling the Effect of the Pre-Test)

Table 7 shows statistically significant differences in the reading comprehension sub-skills of scanning and inferencing across the three groups. The partial eta squared values of scanning and inferencing skills amounted to 0.19 and 0.22, respectively, which attributes 19% and 22% of the variance in the two skills to the instructional modality. The adjusted and unadjusted means were also calculated for the three groups in reading comprehension sub-skills of scanning and inferencing, as shown in Table 8.

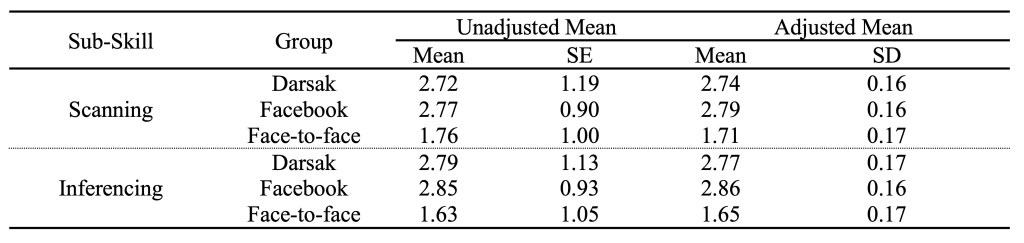

Table 8

Adjusted and Unadjusted Group Means of the Sub-Skills per Instructional Modality (Pre-Test Scores as a Covariate)

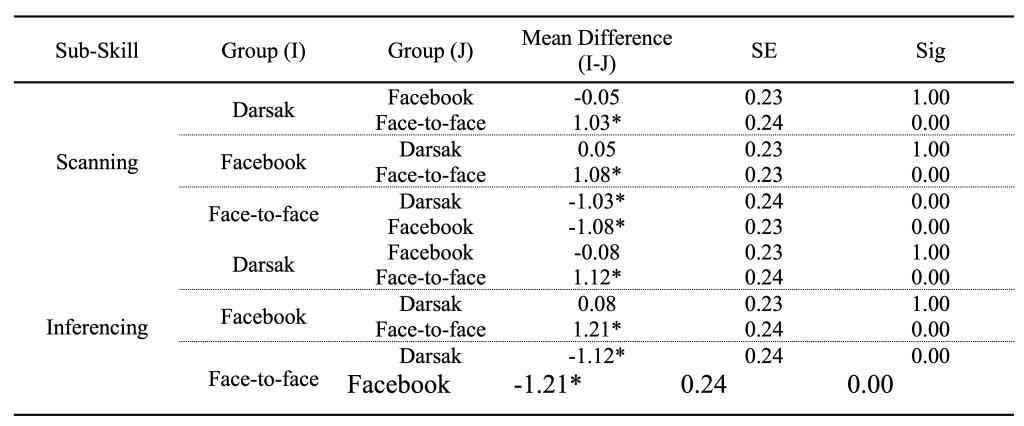

Table 8 shows the means and standard deviations of the reading comprehension sub-skills across the three groups, before and after controlling the pre-test. Differences seem to persist across the three groups even after the differences in the pre-test scores are controlled. To determine the potential significance of these differences, Bonferroni test was used to examine multiple comparisons, as shown in Table 9.

Table 9

Pairwise Differences in Scanning and Inferencing across Groups

Table 9 reveals a statistically significant difference in the post-test performance on scanning and inferencing between the participants of the two experimental groups and those of the control group, in favor of the former. However, no statistically significant differences are found in the two experimental groups’ post-test performance on scanning and inferencing.

Discussion

Integrating self-regulated learning into online instruction involves creating an environment that empowers learners to actively control their learning. In the current study, this was achieved through designing an instructional treatment with clear objectives, detailed guidelines, and regular opportunities for self-assessment. Structured activities on both the Darsak platform and a closed Facebook group raised participants’ awareness of their learning habits, enabling them to make necessary adjustments to improve their learning outcomes in terms of goal-setting and planning, monitoring and reflecting on learning, collaboration and feedback, improvements in reading comprehension, and new learning contexts and controlled environment.

Goal-Setting and Planning

Participants in the experimental groups engaged in goal setting and planning tailored to their needs, pace, and proficiency levels. For instance, participants set specific goals and created detailed plans to achieve them within a pre-set timeframe. This included scheduling tasks such as watching instructional videos, completing readings, and participating in discussion forums.

Monitoring and Reflecting on Learning

Throughout the learning process, participants practiced self-monitoring by regularly checking their progress against their pre-set goals. After completing tasks, they reflected on their understanding by summarizing key points, identifying areas of confusion, and, if necessary, adjusting study strategies. Participants further managed their learning resources by identifying and making use of effective tools and materials (e.g., articles, videos, discussion boards) to support their comprehension.

Collaboration and Feedback

Peer interaction and collaboration further supported self-regulated learning. Through online discussion forums, participants brainstormed ideas, shared strategies, and sought feedback from both teachers and peers on assignments and self-assigned tasks. Regular feedback from the teacher, combined with opportunities for self-correction and reflection, enabled participants to hone their goals and strategies, ultimately achieving better learning outcomes.

Improvements in Reading Comprehension

The study revealed marked improvements in the participants’ reading comprehension, particularly in the subskills of scanning and making inferences. These gains may have been brought about by the following factors:

- Enhanced Interactivity: The experimental groups engaged in interactive reading tasks that offered repeated opportunities for practice over the ten-week treatment. Participants not only did the tasks required of them but also often volunteered to share additional online resources they discovered, fostering a sense of responsibility and ownership over their learning.

- Multimodal Learning: The use of diverse modalities (e.g., videos, electronic quizzes, hyperlinks to reading texts) provided participants with a multi-faceted learning experience, catering to various abilities and learning styles. For many participants, this was their first exposure to such methods, which encouraged proactive and self-motivated learning (e.g., Cinkara & Bagceci, 2013; Zarei & Amani, 2018; Zidat & Djoudi, 2010).

- Flexibility and Personalization: Self-regulated strategies allowed participants to tailor their approaches based on individual preferences and needs, creating personalized learning experiences. This flexibility is particularly valuable in online settings, where limited teacher support can hinder progress (Cleary & Zimmerman, 2004).

- Individualized and Repetitive Tasks: Tasks like videos and electronic worksheets could be accessed repeatedly at the participants’ leisure, allowing them to learn at their own pace. Increased interaction with teachers, peers, and instructional materials beyond the confines of a traditional classroom further enriched the learning experience.

- New Learning Contexts and Controlled Environment: The innovative and interactive online activities on Darsak and Facebook introduced participants to a novel and challenging learning context. They were encouraged to engage actively, contribute meaningfully, and take responsibility for their learning. The controlled online environment minimized distractions and provided the benefits of online instruction without overwhelming learners with the vastness of cyberspace (Zheng et al., 2021).

The current findings underscore the importance of integrating self-regulated learning into online reading instruction, reaffirming its role in fostering meaningful and effective learning experiences. By equipping learners with strategies to plan, monitor, and reflect on their learning, self-regulated learning encourages active engagement and accountability, which are crucial in online settings where teacher presence is often limited. These findings are consistent with prior research that highlights the transformative potential of self-regulated learning in digital environments. Studies by Richardson et al. (2012), Schneider and Preckel (2017), and Schunk and Zimmerman (2007) have shown that self-regulated learning potentially enhances learners’ ability to remain engaged with the content, develop deeper comprehension skills, and achieve better academic outcomes.

Moreover, the emphasis on self-regulated learning is particularly relevant in online education. By fostering independence, self-discipline, and personalized learning approaches, self-regulated learning empowers students to navigate the complexities of digital platforms and adapt to various learning modalities. The alignment of these findings with established research further validates the integration of self-regulated learning as a foundational component of effective online reading instruction, contributing to a more learner-centered and adaptive educational framework.

Pedagogical Implications and Recommendations

The current findings have given rise to several implications, especially for the design and implementation of online reading instruction. Integrating self-regulated learning strategies in online reading instruction, through both Darsak and Facebook, has proven beneficial not only for improving the participants’ ability to scanandmake inferences but also their overall reading comprehension relative to conventional face-to-face instruction.

Teachers are instrumental in helping students develop their self-regulated learning skills, especially in light of reports that many learners find it difficult to self-regulate during online learning (e.g., Garcia et al., 2018; Greene & Azevedo, 2010; Jansen et al., 2020; Winne & Baker, 2013). Teachers’ support is key for learners to set realistic reading goals, monitor their comprehension, and adjust their learning strategies to achieve these goals. Furthermore, self-regulated learning skills can be honed through proper formative assessments (e.g., reflections, self-assessment) and constructive feedback which raise students’ awareness of their progress.

Providing students with the knowledge about and skills of self-regulated learning potentially empowers them to self-initiate and eventually control their own learning. Thus, curriculum designers and textbook writers alike are called upon to integrate self-regulated learning into reading materials through incorporating clear goal setting, self-monitoring, and self-reflection activities. Online reading instruction, with its flexible learning paths, should allow learners to set goals and choose appropriate resources for both their proficiency levels and reading interests.

Given the significant effect of teacher and learners’ roles and characteristics on the success of self-regulated learning (Jouhari et al., 2015), it is crucial to consider self-regulation in both pre-/in- service teacher training and professional development. Training on the theory and implementation of self-regulated learning (e.g., on-line/site training; forming collaborative learning communities among teachers) can develop teachers’ ability to provide scaffolding and support to their learners to encourage self-regulated learning, motivation, and engagement through the adoption of reading materials and activities that match learners’ needs, interests, and real-life contexts. By integrating effective pedagogical practices, teachers can enhance the effectiveness of online reading instruction, fostering independent, motivated, and self-regulated learners. These implications highlight the critical role of self-regulated instruction in supporting students as they navigate the complexities of online learning environments, ultimately contributing to their academic success and lifelong learning skills.

By fostering learner autonomy, self-assessment, and personalized learning strategies, self-regulated learning can potentially increase the effectiveness of online reading instruction for maximum effectiveness and accessibility for all learners. However, the authors acknowledge the challenges involved in implementing self-regulated learning strategies in online reading instruction. Learner interest, discipline, and motivation may constitute significant barriers to effective implementation. Thus, further research is needed to explore both modalities to promote and scaffold self-regulated learning in online and face-to-face instruction to ensure maximum effectiveness.

In light of the current findings, teachers are urged to keep abreast with and be prepared to function in online modalities, be it to teach, assess their students, or display their work. However, a lot of the burden of functioning effectively in these modalities themselves is alleviated as resources and applications abound to help them towards these ends. It is also recommended that more research be conducted on diverse samples and for longer durations to better assess the utility of online learning on both reading and other language skills.

Notes on the Contributors

Ruba Fahmi Bataineh (ORCID: 0000-0002-5454-2206) is a professor of TESOL at the Department of Curriculum and Methods of Instruction at Yarmouk University (Irbid, Jordan). She has published extensively on cross-cultural pragmatics, literacy, CALL, and teacher education in renowned regional and international journals.

Enas Naim Al-Ghoul (ORCID: 0009-0007-0275-8674) is a teacher of English in the Jordanian Ministry of Education and a recent graduate of the PhD Program in TEFL at Yarmouk University (Irbid, Jordan) under Prof. Bataineh’s supervision. Her research interests include literacy, teacher education and CALL.

Rula Fahmi Bataineh (ORCID: 0000-0002-4982-7338) is an assistant professor of Pragmatics at the Department of English for Applied Studies at Jordan University of Science and Technology, Jordan. Her research interests include cross-cultural pragmatics, literacy and CALL.

References

Aghaie, R., & Zhang, L. J. (2012). Effects of explicit instruction in cognitive and metacognitive reading strategies on EFL students’ reading performance and strategy transfer. Instructional Science, 40(6), 1063–1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-011-9202-5.

Ali, R., & Leeds, E. M. (2009). The impact of face-to-face orientation on online retention: A pilot study. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 12(4). https://ojdla.com/archive/winter124/ali124.pdf.

Al-Musili, R., Bataineh, R. F., & Al Jamal, D. (2022). Jordanian EFL learners’ perception of the utility of synchronous and asynchronous online instruction. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(3), 5973–5986.

Aydin, S. (2012). A review of research on Facebook as an educational environment. Educational Technology Research and Development, 60(6), 1093–1106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ s11423-012-9260-7.

Barnard, L., Lan, W. Y., To, Y. M., Paton, V. O., & Lai, S. L. (2009). Measuring self-regulation in online and blended learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 12(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.10.005.

Barrot, J. (2018). Facebook as a learning environment for language teaching and learning: A critical analysis of the literature from 2010 to 2017. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34(4). 863–875. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12295.

Bataineh, M. T., & Bataineh, R. F. (2024). Personal learning environment and writing performance: The case of Jordanian young EFL learners. SISAL Journal: Studies in Self-Access Learning, 15(1), 65-85. https://doi.org/10.37237/150102.

Bataineh, R. F., Migdadi, A., & Al-Alawneh, M. K. (2020). Does Web 2.0-supported project-based instruction improve Jordanian EFL learners’ speaking performance? Teaching English with Technology, 20(3), 25–39. http://www.tewtjournal.org

Batshon, D., & Shahzadeh, Y. (2020). Education in the time of COVID-19 in Jordan: A roadmap for short, medium, and long-term responses. Centre of Lebanese Studies, Lebanese American University. https://carleton.ca/lerrn/wp-content/uploads/education-in-the-time-of-covid19-in-jordan.pdf.

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. Routledge.

Bi, J., Javadi, M., & Izadpanah, S. (2023). The comparison of the effect of two methods of face-to-face and E-learning education on learning, retention, and interest in English language course. Education and Information Technologies, 28(10), 13737–13762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11743-3.

Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 417–444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143823.

Blattner, G., & Fiori, M. (2009). Facebook in the language classroom: Promises and possibilities. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 6(1), 17–28.

Carneiro, R., Lefrere, P., Steffens, K., & Underwood, J. (2011). Self-Regulated learning in technology enhanced learning environments: A European perspective. Sense Publishers.

Choi, Y., Zhang, D., Lin, C., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Self-regulated learning of vocabulary in English as a foreign language. Asian EFL Journal Quarterly, 20(3), 54–82. https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/handle/10871/31414

Cinkara, E., & Bagceci, B. (2013). Learners’ attitudes towards online language learning; and corresponding success rates. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 14(2), 118–130. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/tojde/issue/16896/176049

Cleary, T. J., & Platten, P. (2013). Examining the correspondence between self‐regulated learning and academic achievement: A case study analysis. Education Research International, 2013(1), 272560. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/272560.

Cleary, T. J., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2004). Self‐regulation empowerment program: A school‐based program to enhance self‐regulated and self‐motivated cycles of student learning. Psychology in the Schools, 41(5), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10177.

Daniela, P. (2015). The relationship between self-regulation, motivation and performance at secondary school students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 191, 2549–2553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.410.

de Fátima Goulão, M., & Menedez, R. C. (2015). Learner autonomy and self-regulation in eLearning. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 1900–1907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.853.

Delen, E., & Liew, J. (2016). The use of interactive environments to promote self-regulation in online learning: A literature review. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 15(1), 24–33. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1095976

Dembo, M. H., & Eaton, M. J. (2000). Self-regulation of academic learning in middle-level schools. The Elementary School Journal, 100(5), 473–490. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/499651

Dembo, M. H., Junge, L. G., & Lynch, R. (2006). Becoming a self-regulated learner: Implications for web-based education. In H. F. O’Neil, & R. S. Perez (Eds.), Web-based learning: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 185–202). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dent, A. L., & Koenka, A. C. (2016). The relation between self-regulated learning and academic achievement across childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 28, 425–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9320-8.

Dignath, C., Buettner, G., & Langfeldt, H. P. (2008). How can primary school students learn self-regulated learning strategies most effectively?: A meta-analysis on self-regulation training programs. Educational Research Review, 3(2), 101–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2008.02.003.

Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (2012). How to design and analyze surveys in second language acquisition research. In A. Mackey, & S. M. Gass (Eds.), Research methods in second language acquisition: A practical guide (pp. 74–94). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444347340.ch5.

Ekoc, A. (2014). Facebook groups and as supporting tool for language classrooms. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 15(3), 18–26 https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.13403.

Faryadi, Q. (2017). Effectiveness of Facebook in English language learning: A case study. Open Access Library Journal, 4(11), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1104017.

Garcia, R., Falkner, K., & Vivian, R. (2018). Systematic literature review: Self-regulated learning strategies using e-learning tools for computer science. Computers & Education, 123, 150–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.006

Garrison, D. R., & Cleveland-Innes, M. (2005). Facilitating cognitive presence in online learning: Interaction is not enough. The American Journal of Distance Education, 19(3), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15389286ajde1903_2.

Greene, J. A., & Azevedo, R. (2010). The measurement of learners’ self-regulated cognitive and metacognitive processes while using computer-based learning environments. Educational Psychologist, 45(4), 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461 520.2010.515935.

Ha, C. (2023). Students’ self-regulated learning strategies and science achievement: Exploring the moderating effect of learners’ emotional skills. Cambridge Journal of Education, 53(4), 451–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2023.2175787.

Hannafin, M. J., & Hannafin, K. M. (2010). Cognition and student-centered, web-based learning: Issues and implications for research and theory. In J. Spector, D. Ifenthaler, P. Isaias, P., Kinshuk, & D. Sampson (Eds.), Learning and instruction in the digital age (pp. 11–23). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1551-1_2.

Harmon, O. R., & Lambrinos, J. (2006). Online format vs. live mode of instruction: Do human capital differences or differences in returns to human capital explain the differences in outcomes? Economics Working Papers. Paper 200607. http://digitalcommons.uconn. edu/econ_wpapers/200607.

Helms, J. L. (2014). Comparing student performance in online and face-to-face delivery modalities. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v18i1.348.

Hodges, C. B., Moore, S., Lockee, B. B., Trust, T., & Bond, M. A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review.

Istifci, I., & Goksel, N. (2022). The relationship between digital literacy skills and self-regulated learning skills of open education faculty students. English as Foreign Language International Journal, 2(1), 59–81. https://doi.org/10.56498/164212022.

Jansen, R. S., van Leeuwen, A., Janssen, J., Conijn, R., & Kester, L. (2020). Supporting learners’ self-regulated learning in Massive Open Online Courses. Computers & Education, 146, 103771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103771.

Jin, S. H., Im, K., Yoo, M., Roll, I., & Seo, K. (2023). Supporting students’ self-regulated learning in online learning using artificial intelligence applications. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(37). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00406-5.

Johnson, D., & Palmer, C. C. (2014). Comparing student assessments and perceptions of online and face-to-face versions of an introductory linguistics course. Online Learning Journal, 19(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v19i2.449.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2009). An educational psychology success story: Social interdependence theory and cooperative learning. Educational Researcher, 38(5), 365–379. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09339057.

Jouhari, Z., Haghani, F., & Changiz, T. (2015). Factors affecting self-regulated learning in medical students: A qualitative study. Medical Education Online, 20(1), 28694. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v20.28694.

Juang, Y. (2010). Integrating social networking site into teaching and learning. Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Computers in Education (pp. 240–251). Asia-Pacific Society for Computers in Education Putrajaya, Malaysia.

Kabilan, M. K., Ahmad, N., & Abidin, M. J. Z. (2010). Facebook: An online environment for learning of English in institutions of higher education? Internet and Higher Education, 13(4), 179–187. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/108382/.

Kizilcec, R. F., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., & Maldonado, J. J. (2017). Self-regulated learning strategies predict learner behavior and goal attainment in Massive Open Online Courses. Computers & Education, 104, 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu. 2016.10.001.

Koksal, D., & Dundar, S. (2018). Developing a scale for self-regulated L2 learning strategy use. Hacettepe University Journal of Education, 33(2), 337–352. https://doi.org/10.16986/ HUJE.2017033805.

Lashari, A. A., Umrani, S., & Buriro, G. A. (2021). Learners’ self-regulation and autonomy in learning English language. Pakistan Languages and Humanities Review, 5(2), 115–130. http://doi.org/10.47205/plhr.2021(5-II)1.11.

Lee, C. M. (2024). Online learning versus face to face learning toward students: Which can be an effective way of learning methodology to our current educational system? Mendely Data, V1. https://doi.org/10.17632/m2prrm7c3g.1.

Lewis, T., & Vialleton, E. (2011). The notions of control and consciousness in learner autonomy and self-regulated learning: A comparison and critique. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 5(2), 205–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2011.577535.

Loyens, S. M. M., Magda, J., & Rikers, R. M. J. P (2008). Self-directed learning in problem-based learning and its relationship with self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 20(4), 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-008-9082-7.

Magno, C. (2010). The role of metacognitive skills in developing critical thinking. Metacognition and Learning, 5(2), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-010-9054-4.

McCombs, B.L. (2013). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: A phenomenological view. In B.J. Zimmerman, & D.H. Schunk (Eds.), Self-regulated learning and academic achievement (pp. 63–117). Routledge.

McKee, M., & Stuckler, D. (2020). If the world fails to protect the economy, COVID-19 will damage health not just now but also in the future. Nature Medicine, 26(5), 640–642. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0863-y.

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2010). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. Washington, D.C.: U.S Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development Policy and Program Studies Service. https://repository.alt.ac.uk/629/1/US_DepEdu_Final_report_2009.pdf.

Miele, D. B., & Scholer, A. A. (2016). Self-regulation of motivation. In K. R. Wentzel, & D. B. Miele(Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 363–384). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315773384.

Miller, R. B., & Brickman, S. J. (2004). A model of future-oriented motivation and self-regulation. Educational Psychology Review, 16(1), 9–33. https://doi.org/10.1023/ B:EDPR.0000012343.96370.39.

Ministry of Education, Jordan (2020). Education during emergency plan, 2020/2022. https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/en/2020/education-during-emergency-plan-edep-20202022-6936

Mokhtari, K., & Reichard, C. A. (2002). Assessing students’ metacognitive awareness of reading strategies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0663.94.2.249

Molenaar, I., Horvers, A., Dijkstra, S. H. E., & Baker, R. S. (2019). Designing dashboards to support learners’ self-regulated learning. Companion Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge (LAK19), pp. 764-775). https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/201823/201823.pdf? sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Mulling, A. B. F., & Watkins, P. (2022). Reading in self-access material: What can we learn from self-instructed learners and their reported experience? The Reading Matrix: An International Online Journal, 22(1), 37–55.

Murray, G. (2014). The social dimensions of learner autonomy and self-regulated learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(4), 320–341. https://doi.org/10.37237/050402

Nakata, Y. (2014). Self-regulation: Why is it important for promoting learner autonomy in the school context? Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(4), 342–356. https://doi.org/10.37237/050403

Navarro, P., & Shoemaker, J. (2000). Performance and perceptions of distance learners in cyberspace. American Journal of Distance Education, 14(2), 15–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923640009527052.

Nguyen, T. (2015). The effectiveness of online learning: Beyond no significant difference and future horizons. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 11(2), 309–319. https://jolt.merlot.org/Vol11no2/Nguyen_0615.pdf.

Oxford, R. L. (2016). Teaching and researching language learning strategies: Self-Regulation in context. Routledge.

Öz, E., & Şen, H. Ş. (2021). The effect of self-regulated learning on students’ lifelong learning and critical thinking tendencies. Elektronik Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 20(78), 934–960. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/1379954

Peverly, S. T., Brobst, K. E., Graham, M., & Shaw, R. (2003). College adults are not good at self-regulation: A study on the relationship of self-regulation, note taking, and test taking. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(2), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.2.335.

Pintrich, P. R. (2004). A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Educational Psychology Review, 16(4), 385–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-004-0006-x.

Rasekh, Z. E., & Ranjbary, R. (2003). Metacognitive strategy training for vocabulary learning. TESL-EJ, 7(2), 1–15. https://tesl-ej.org/ej26/a5.html.

Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026838.

Sansone, C., Fraughton, T., Zachary, J. L., Butner, J., & Heiner, C. (2011). Self-regulation of motivation when learning online: The importance of who, why and how. Educational Technology Research and Development, 59, 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-011-9193-6.

Schneider, M., & Preckel, F. (2017). Variables associated with achievement in higher education: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 143(6), 565–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000098.

Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2007). Influencing children’s self-efficacy and self-regulation of reading and writing through modeling. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 23(1), 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560600837578.

Simpson, M. N. (2011). ESL@Facebook: A teacher’s diary on using Facebook. Teaching English with Technology, 12(3), 36–48. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1144966.pdf

Skinner, D. E., Saylors, C. P., Boone, E. L., Rye, K. J., Berry, K. S., & Kennedy, R. L. (2015). Becoming lifelong learners: A study in self-regulated learning. Journal of Allied Health, 44(3), 177–182. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26342616/

Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65–94. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17201571/

Taranto, D., & Buchanan, M.T. (2020). Sustaining lifelong learning: A self-regulated learning (SRL) approach. Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education, 11(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.2478/dcse-2020-0002

Teng, L. S., & Zhang, L. J. (2018). Empowering learners in the second/foreign language classroom: Can self-regulated learning strategies enhance learning achievement? Educational Psychology Review, 30(2), 545-567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2019.100701.

Tseng, W. T., Dörnyei, Z., & Schmitt, N. (2006). A new approach to assessing strategic learning: The case of self-regulation in vocabulary acquisition. Applied Linguistics, 27(1), 78-102. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ami046.

Vansteenkiste, M., Sierens, E., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., Dochy, F., Mouratidis, A., Aelterman, N., Haerens, L., & Beyers, W. (2012). Identifying configurations of perceived teacher autonomy support and structure: Associations with self-regulated learning, motivation and problem behavior. Learning and Instruction, 22(6), 431–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.04 .002.

Wang, C., & Bai, B. (2017). Validating the instruments to measure ESL/EFL learners’ self-regulated learning strategies. TESOL Quarterly, 51(4), 932–947. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.355.

Wang, Y. (2023). Enhancing English reading skills and self-regulated learning through online collaborative flipped classroom: A comparative study. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1255389. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255389.

Watson, J., & Johnson, L. K. (2011). Online learning: A 21st century approach to education. In G. Wan, & D. Gut (Eds.), Bringing schools into the 21st century. Explorations of educational purpose. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0268-4_10.

Winne, P. H. (1995). Inherent details in self-regulated learning. Educational Psychologist, 30(4), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3004_2.

Winne, P. H., & Baker, R. S. J. D. (2013). The potentials of educational data mining for researching metacognition, motivation, and self-regulated learning. Journal of Educational Data Mining, 5(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.2.2.131.

Xu, D., & Jaggars, S. S. (2013). The impact of online learning on students’ course outcomes: Evidence from a large community and technical college system. Economics of Education Review, 37, 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.08.001.

Xu, Z., Zhao, Y., Liew, J., Zhou, X., & Kogut, A. (2023). Synthesizing research evidence on self-regulated learning and academic achievement in online and blended learning environments: A scoping review. Educational Research Review, 39, 100510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2023.100510.

Yang, M. S., & Kim, J. K. (2014). Correlation between digital literacy and self-regulated learning skills of learners in university e-learning environment. Education, 3(13), 80–83.

Zarei, A., & Amani, M. (2018). The effect of online tools on L2 reading comprehension and vocabulary learning. Journal of Teaching Language Skills, 37(3), 211–238. https://doi.org/10.22099/jtls.2019.32248.263.

Zheng, L. (2016). The effectiveness of self-regulated learning scaffolds on academic performance in computer-based learning environments: A meta-analysis. Asia Pacific Education Review, 17, 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-016-9426-9.

Zheng, M., Bender, D., & Lyon, C. (2021). Online learning during COVID-19 produced equivalent or better student course performance as compared with pre-pandemic: Empirical evidence from a school-wide comparative study. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02909-z.

Zidat, S., & Djoudi, M. (2010). Effects of an online learning on EFL university students’ English reading comprehension. International Review on Computers and Software, 5(2), 186–192. https://pg.univ-batna2.dz/publications/effects-online-learning-efl-university-students%E2%80%99-english-reading-comprehension

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–39). Academic Press.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Bandura, A. (1994). Impact of self-regulatory influences on writing course attainment. American Educational Research Journal, 31(4), 845–862. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163397.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1988). Construct validation of a strategy model of student self-regulated learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(3), 284–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.3.284

Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (2011). Self-regulated learning and performance: An introduction and an overview. In B. J. Zimmerman, & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (pp.15–26). Routledge.

Appendices

Appendix A

Sample Lesson Plan (Darsak)

Week 3: Lesson 3 (Two Sessions)

Grade: 9th

Module: 5

Lesson: 3 (A Miser’s Final Wish)

Outcomes

By the end of the lesson, students will be able to:

- analyze the text and make inferences

- demonstrate understanding of the text about money

- reflect on personal attitudes towards money and compare them to those of the characters

- engage in self-assessment and peer feedback

Materials

Student’s Book, page 50, Exercises 1, 3 & 4

Darsak Platform (for delivery and assessment)

Instructional Strategy

Online Instruction (via Darsak Platform)

Active engagement through self-reflection, peer feedback, and self-assessment

Asynchronous learning with teacher-guided prompts for reflection

Assessment

Formative assessment through responses, self-reflection, and peer feedback.

Summative assessment: Worksheet/ test at the end of the module

Estimated Time

1 hour session broadcasted on Darsak Platform

Participants

39 students

Procedures

1. Login and Introduction (5 minutes)

Activity: Students log into the Darsak Platform using their national numbers. The teacher introduces the lesson and briefly explains the outcomes.

Learner Autonomy: Students take responsibility for logging in and engaging with the platform.

2. Independent Learning (15 minutes)

Activity: Students follow the recorded lesson on the platform. The lesson will cover the background of the story, key vocabulary, and the main themes (money, values, and attitudes toward wealth).

Learner Autonomy: Students are encouraged to pause the video as needed, take notes, and reflect on the content.

Self-reflection: After watching the video, students are prompted to ask themselves, “What did I learn about Mr. Lin’s attitude toward money?”

3. Assignment: Comprehension Questions (10 minutes)

Activity: The teacher posts a set of questions for students to answer asynchronously on the platform:

1. What shows that Mr. Lin is a hardworking man?

2. Why was he considered a miser?

3. Where did he keep all the money he saved?

4. What did he ask his wife to do with all his money when he died?

5. What did Mrs. Lin do with all his money after he died?

Learner Autonomy: Students are encouraged to answer the questions based on their own understanding of the text and make inferences.

Self-assessment: Students are asked to rate their confidence in their answers on a scale of 1–3 (Not confident – Very confident) and note areas where they feel uncertain.

4. Peer Feedback (15 minutes)

Activity: After submitting their answers, students review and comment on the responses of two peers. They can ask questions, provide feedback, or offer alternative interpretations of the story.

Peer Feedback: This allows students to learn from each other’s interpretations and gain a deeper understanding of the text.

Self-reflection: Before providing feedback, students are asked to reflect on their own answers and consider how they could improve them based on peer responses.

5. Teacher Feedback (10 minutes)

Activity: The teacher provides individualized feedback through platform messages, highlighting strengths and areas for improvement. The teacher may also ask guiding questions to prompt further reflection.

Self-assessment: Students are encouraged to assess their own learning after receiving feedback. They should reflect on what feedback was most helpful and how they can improve their understanding.

6. Final Reflection (5 minutes)

Activity: Students complete a short self-reflection form after the lesson, answering the following questions:

1. What did I learn today?

2. How well did I understand the text?

3. What strategies did I use to improve my understanding?

4. What areas do I still need to work on?

Learner Autonomy: Students take responsibility for their own learning and identify areas where they need further improvement.

Self-assessment: Based on their reflections, students rate their overall performance in the lesson.

7. Conclusion & Goal Setting (5 minutes)

Activity: The teacher briefly summarizes the key points of the lesson and encourages students to set a personal goal for their next lesson.

Goal Setting: Students write down one specific goal they want to achieve in the next session (e.g., improve reading comprehension, participate more in discussions, etc.).

Appendix B

Sample Lesson Plan (Facebook)

Week 3: Lesson 3 (Two Sessions)

Grade: 9th

Module: 5

Lesson: 3 (A Miser’s Final Wish)

Outcomes

By the end of the lesson, students will be able to:

- analyze the text and make inferences

- demonstrate understanding of the text about money

- reflect on personal attitudes towards money and compare them to those of the characters

- engage in self-assessment and peer feedback.

Materials

Student’s Book, page 50, Exercises 1, 3 & 4

Graphic organizers (e.g., mind maps, Venn diagrams)

Instructional Strategy

Online Instruction (Facebook: Closed group)

Active participation through comments, reflections, and self-assessments

Assessment

Formative: Peer and self-assessment through comments and reflections.

Summative: Worksheet/ test at the end of the module

Estimated Time

2 periods, 30 minutes each

Participants

39 students

Procedures

First Period (30 minutes)

1. Engagement and Reflection (5 minutes)

The teacher starts a live video and poses a reflective question: “Do you receive pocket money from your parents? If not, imagine you did. Would you prefer to save or spend it? Why?”

Learner autonomy: Students are invited to share their opinions in the comments. The teacher encourages students to reflect on how their choices may relate to the behavior of the characters in the story.

Self-assessment: Students think about their own financial habits and make connections to the text.

2. Text Reading and Vocabulary (5 minutes)

Students read the story individually and highlight words/phrases they do not understand. They can use a dictionary or context clues to infer meanings.

Learner autonomy: Students take responsibility for their vocabulary learning.

Self-assessment: After reading, students assess their understanding of the text and make a note of any areas of difficulty for future reference.

3. Discussion and Personal Reflection (5 minutes)

Students write in the comments if they agree or disagree with Mrs. Lin’s actions and explain why.

Self-assessment: Students reflect on their own values related to money (e.g., spending vs. saving).

4. Analyzing the Questions (5 minutes)

Students read and analyze the questions in Exercise 3 on page 51 (“Do you agree with the statement ‘to make a lot of money and spend as little as possible’? Why/Why not?”).

Learner autonomy: Students respond with personal opinions and engage in discussions with peers, justifying their answers.

Self-assessment: Students assess their ability to support their arguments with evidence from the story.

5. Peer Feedback and Emoji Voting (5 minutes)

After submitting their answers, students review their peers’ responses in the comments section and vote using emojis to express agreement or disagreement.

Peer-assessment: Students evaluate each other’s responses and provide constructive feedback.

Self-reflection: After receiving feedback, students reflect on the strength of their arguments and consider revising their answers if necessary.

6. Sentence Completion (3 minutes)

Students complete sentences in Exercise 4 from memory, using their understanding of the story.

Learner autonomy: Students apply their knowledge to complete the exercise independently.

7. Review and Reflect (2 minutes)

Students share their completed sentences in the comments and review their answers.

Self-assessment: They reflect on their progress in understanding the text and identify areas they still need to improve.

8. Closure and Replay Option (End of Session)

The teacher saves the live video and encourages students to replay it for review.

Self-reflection: Students are encouraged to reflect on their learning and identify areas where they feel confident or need more practice.

Second Period (30 minutes)

9. Silent Rereading (5 minutes)

Students are asked to reread the story silently and underline key passages that support their answers to the discussion questions.

Learner autonomy: Students take ownership of their reading and notetaking.

Self-assessment: They assess how well they understood the text upon the second reading and check for comprehension.

10. Group Discussion and Critical Thinking (10 minutes)

The teacher asks the following comprehension questions:

What shows that Mr. Lin is a hardworking man?

Why was he considered a miser?

Where did he keep all the money he saved?

What did he ask his wife to do with his money when he died?

What did she do with it?

Peer assessment: Students write their answers in the comments and engage with peers’ responses, providing feedback.

Reflection: Students consider how their answers might differ from their peers’ and reflect on different interpretations.

11. Synthesis and Peer Review (10 minutes)

Students review all answers in the comments section and evaluate the depth of each response.

Self-assessment: Students assess how well their understanding aligns with the text and adjust any misunderstandings.

Peer assessment: Students provide constructive feedback to each other in the comments.

12. Feedback and Teacher Guidance (5 minutes)

The teacher provides feedback using emojis and brief comments to encourage deeper analysis.

Self-reflection: Students are encouraged to ask follow-up questions based on the feedback they receive.

13. Summary and Graphic Organizer (5 minutes)

Students are asked to summarize the story in their own words using a graphic organizer (e.g., mind map, Venn diagram).

Learner autonomy: Students decide which format best helps them organize their understanding of the text.

Self-assessment: After completing the summary, students reflect on how well they understood the main ideas of the story.

14. Homework: Graphic Summary Submission

For homework, students refine their summaries and submit them on the closed group, explaining their reasoning.

Self-reflection: Students are encouraged to assess the clarity and completeness of their summary before submission.

Appendix C

Sample Lesson Plan (Control Group (Face-to-Face))

Week 3: Lesson 3

Grade: 9th

Module: 5

Lesson: 3 (A Miser’s Final Wish)

Outcomes

By the end of the lesson, students will be able to:

- comprehend the text (with accuracy)

- identify key information in a text.

- make inferences based on the text

Materials

Student’s Book, page 50, Exercises 1, 3 & 4

Pictures related to the text

Whiteboard and markers

Instructional Strategy

Teacher presentation

Students’ participation (questions)

Assessment

Formative: Teacher assesses students’ answers to the questions (for understanding and accuracy).

Summative: Worksheet/ test at the end of the module

Estimated Time

1 class period, 45 minutes

Participants

37 students

Procedures

1. Introduction (10 minutes)

The teacher shows students the pictures related to the text.

The teacher reads the title of the text aloud and discusses any vocabulary or context to ensure understanding.

2. Independent Reading (5 minutes)

Students read through the text individually.

The teacher circulates the room to support students who may struggle with comprehension.

3. Question Review (10 minutes)

The teacher reads the questions related to the text aloud with the class for students to keep in mind as they read and circle information in the text that will help them answer the questions.

4. Pair Work (5 minutes)

In pairs, students scan the text for specific information to answer the questions.

5. Rereading and Discussion (10 minutes)

Students re-read the text in their pairs, making inferences and clarifying answers.

The teacher guides the discussion, prompting students to think critically about their answers. Afterward, students check each other’s answers and provide feedback.

6. Conclusion (5 minutes)

The teacher wraps up the lesson by reviewing key points from the discussion.

The teacher corrects answers and provides feedback on common misunderstandings.

The teacher assigns follow-up questions for homework.

Appendix D

Sample Worksheets

Worksheet 1: Understanding the Text and Personal Reflection

Instructions for Submission: Submit your answers and reflections on the closed group by replying to the teacher’s post.

Objective: To assess students’ understanding of the story and connect it to their personal values and reflections on money

Section 1: Comprehension Check

Answer each of the following questions based on your understanding of the story. Be sure to refer to specific parts of the text to support your answers.

1. What shows that Mr. Lin is a hardworking man?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

2. Why was Mr. Lin considered a miser?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

3. Where did Mr. Lin keep all the money he saved?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

4. What did Mr. Lin ask his wife to do with his money after he died?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

5. What did Mrs. Lin do with his money after his death, and why?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Section 2: Personal Reflection on Money (5 minutes)

1. Do you agree with Mr. Lin’s approach to money (saving as much as possible and spending as little as possible)? Why or why not?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

2. How do your views on money compare to Mr. Lin’s? Are you more of a saver or a spender?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

3. What would you do if you were in Mrs. Lin’s position? Would you handle Mr. Lin’s money differently? Explain why.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Section 3: Self-assessment on Understanding (5 minutes)

Reflect on your comprehension of the story and answer the following questions:

1. What parts of the story did you understand well?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

2. What parts of the story were challenging for you to understand?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

3. What strategies did you use to improve your understanding of the text?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Section 4: Peer Feedback (5 minutes)

Review the answers your peers have posted in the group. Choose one or two responses that you found particularly interesting to answer the questions below:

1. What did you find most interesting in your peer’s answers?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

2. How can your peer improve or clarify their answers.

Offer suggestions

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Worksheet 2: Synthesis, Graphic Organizing, and Self-Reflection

Instructions for Submission: Post a photo or screenshot of your graphic organizer and submit your Self-assessment responses in the comments section of the group.

Objective: to summarize the text, organize ideas visually, and reflect on learning progress.

Section 1: Graphic Organizer (10 minutes)

Create a graphic organizer (mind map, Venn diagram, or concept map) to summarize the key points of the story. Focus on the following aspects:

- Mr. Lin’s attitude towards money.

- Mrs. Lin’s reaction to his money.

- Key events that led to Mr. Lin’s actions and Mrs. Lin’s response.

- The moral of the story or lesson learned.

Section 2: Self-Reflection on Understanding (5 minutes)

Now that you’ve completed your graphic organizer, take a moment to reflect on your understanding of the story and your learning process.

1. How confident do you feel about your understanding of the story?

[ ] Very confident

[ ] Somewhat confident

[ ] Not confident at all

Explain your answer.

2. What new insights did you gain from completing the graphic organizer?

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

3. What aspects of the story do you still have questions about or need further clarification on?

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Section 3: Self-assessment on Learning (5 minutes)

Reflect on how effectively you participated in the lesson and whether you met your learning goals. Answer the following questions to assess your progress.

1. Did you actively engage in the group discussion and comments?

[ ] Yes, I participated a lot

[ ] Yes, I tried but could have done better

[ ] No, I did not participate

2. Did you apply strategies (e.g., context clues, asking questions) to understand difficult parts of the story?