Mohannad Bataineh, Yarmouk University, Jordan

Ruba Bataineh, Yarmouk University, Jordan. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5454-2206

Bataineh, M., & Bataineh, R. (2024). Personal learning environment and writing performance: The case of Jordanian young EFL learners. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.37237/150102

[Pagnated PDF version to follow]

Abstract

This study examines the potential effect of incorporating personal learning environment-based instruction on young EFL learners’ writing performance. A quasi-experimental design was used as two intact sixth-grade sections of twenty pupils each from Juffein Primary School for Boys in the Directorate of Education of the Koura District, Irbid (Jordan) constituted the sample of the research. With a toss of a coin, one section was assigned as the control group and the other as the experimental group. A ten-week instructional treatment based on the creation of individual personal learning environments was designed and implemented with the experimental group following proper validation procedures. The control group was instructed using the guidelines of the prescribed Teacher’s Book. A writing test was also designed, validated, and administered to all 40 participants before and after the treatment. The findings revealed that the experimental group outperformed the control group with statistically significant differences found between the two groups in both overall writing and writing features (viz., ideas, organization, sentence fluency, conventions, and legibility). Relevant recommendations and pedagogical recommendations are put forth.

Keywords: Jordan, personal learning environment, reflection, technology integration, writing

Moving from a teacher-centered to student-centered classroom has been one of the most notable educational innovations in the past few decades. This shift has been brought about by an ever-accelerating tempo of knowledge development, technological advancements, individual students’ needs, and the growing inability of traditional educational systems to fulfill emerging labor market requirements.

Technology has been instrumental in all sectors, and education is no exception. The rapid advancement of information technology has had an impact on education (Schaffert & Hilzensauer, 2008) as technology has capabilities reported to catalyze foreign language education in general and foreign writing education in particular (Davies et al., 2011).

Technological advances have been put to use in facilitating language teaching and learning. Language learners, especially those of a foreign language, need more support and extensive practice. Even though personal learning environments (henceforth, PLEs) may be created without technology innovative technologies has made the creation and use of PLEs both easier and more effective (Reinders, 2014).

Writing, rudimentary for human communication, is the process of thinking up, organizing, and documenting ideas and experiences (Nunan, 1999; Olshtain, 2001; Sokolik, 2003) for communicative purposes. It entails creating a series of phrases that are connected in a specific way while making use of graphic symbols to denote the writer’s communicative intent (Graham et al., 1993) through a variety of processes, including linguistic fluency, association, reasoning, and goal-thinking (Shah et al., 2013).

Even though the acronym PLE is as recent as the early 2000s (Brown, 2010; Severance et al., 2008; Taraghi et al., 2009), both the concept and the term can be traced back to the 1960s to denote the individualization and personalization of instruction. However, PLE, as we know it today, had not emerged with the advent of technology in the twentieth century but rather came into being following several technological innovations which made it not only possible but also more efficient (Milligan et al., 2006). Thus, “PLE is more a pedagogical change in the use of technologies than a technological change in educational systems” (Bartolomé & Cebrian-de-la-Serna, 2017, p. 24) as it involves the use of the same tools used in both traditional classrooms and more innovative learning management systems (e.g., mind mapping, reflection, technology integration) to respond to the demands of personalized learning.

Innovative teaching/learning strategies are needed to better support teachers in facilitating the learning process through allowing learners the tools they need to adapt to the dynamicity of education. Personal learning environments is an alternative which has been reported to support students’ learning in various disciplines, particularly in foreign language education.

Personal learning environment is an environment or setting where students use a range of resources, tools, connections, and activities to further their education (Adell & Castañeda Quintero, 2010). It is a collaborative e-learning system which is both self-directed and used for personalizing learning (Harmelen, 2006, 2008), a framework which enables learners to manage their own learning environments (Ullrich et al., 2008), and a set of resources, either digital or non-digital, used by learners for goal-setting, material selection, or assessment (Reinders, 2014). PLE is also viewed as a tool to organize learning rather than an application or a piece of software (Wilson, 2008) and a “pedagogical approach for both integrating formal and informal learning using social media and supporting student self-regulated learning in higher education contexts” (Dabbagh & Kitsantas, 2012, p. 3).

PLE has gained such popularity that it was presented as an eclectic approach which may change the face of global educational delivery (Adell & Castañeda Quintero, 2010; Milligan et al., 2006). Its three pillars of are self-direction, content production, and interaction with numerous resources (Attwell, 2007; Schaffert & Hilzensauer, 2008; Zhou, 2013). Through these tools, PLE allows learners to learn collaboratively, control their learning resources, manage their participatory activities, integrate their learning (Milligan et al., 2006), develop autonomy, and prepare for lifelong learning (Reinders, 2014).

In the current research, PLE is realized through a set of digital and non-digital tools, referred to as PLE-enhancing tools. Flipped learning, reflection, mind mapping, and technology integration are the major components of the treatment. Through these tools, the treatment is learner-centered with the teacher acting more as the ‘guide on the side’ than the center of the teaching/learning process. Technology integration is realized through the use of YouTube and Kidblog, a popular educational blogging platform for primary school students (Boling et al., 2008), which allows learners an interactive environment where they can engage and share ideas (Sykes et al., 2008).

There is ample empirical evidence for the utility of the PLE-enhancing tools used in this research in writing instruction. Flipped learning has been found to catalyze writing abilities on both the micro- and macro-levels (e.g., Abdelrahman et al., 2017; Ahmad, 2016; Chai & Hamid, 2023; Ekmekci, 2017). A plethora of research (e.g., Herder et al., 2018; Klein, 2012; Myhill, 2009; Vass et al., 2008) reports on the positive effect of reflection on developing writing proficiency. Similarly, mind-mapping is also reported to significantly improve overall performance in writing (e.g., Al-Zyoud et al., 2017; Pradasari & Pratiwi, 2018; Soliman, 2021; Yawiloeng, 2022) and other skills (e.g., Bataineh & Al-Majali, 2023; Bataineh & Alqatanani ,2019). Technology integration (e.g., blogging, YouTube videos, blended learning) is also reported to significantly improve writing skills (e.g., Anggraeni & Yasa, 2012; Faridha, 2019; Keshta & Harb, 2013; Noytim, 2010; Özdemir & Aydın, 2015; Styati, 2016).

Problem, Purpose and Research Questions

In the Jordanian EFL context, instruction is carried out using a twelve-level textbook series, Action Pack, prescribed by the Ministry of Education (henceforth, MoE) to be taught to all students in both basic and secondary education. The series is informed by the General Guidelines and General and Specific Outcomes for English Language Curriculum for the Basic and Secondary Stages in Jordan.

As the importance of the four language skills is well-documented in foreign language education research, Jordan has implemented a series of reforms which targeted the curricula, teacher training, and instructional infrastructure to facilitate teaching and learning English, which is taught as a foreign language in all Jordanian schools starting at first grade (and most recently Kindergarten at age 5). However, Jordanian students are reported to lag behind in overall English proficiency (Bani Younis & Bataineh, 2016; Bataineh & Salah, 2017) in general and in writing in particular (Al-Hamad et al., 2019; Bataineh & Bani Younis, 2016; Bataineh & Obeiah, 2016). As EFL practitioners at both the school and tertiary levels, the researchers have experienced first-hand their students’ weakness and reluctance to engage in writing.

Being a sixth-grade teacher, the first researcher has also experienced first-hand his students struggle with English in general and writing in particular. There have been reports that the reported weakness may be attributed to insufficient writing instruction as most teachers, across all grade levels, tend to avoid writing and resort to assigning it as homework in the final moments of the lesson. Therefore, this research seeks to examine the effectiveness of PLE-enhanced instruction (viz., flipped learning, reflection, mind mapping, and technology integration (Kidblog and YouTube)) on sixth-grade students’ writing performance as compared to the traditional Teacher’s Book-based instruction. More specifically, the research seeks answers to the following questions:

- Are there any statistically significant differences (at α=0.05) in Jordanian EFL sixth-grade students’ overall writing performance, which may be attributed to instructional modality (conventional vs. PLE-based)?

- Are there any statistically significant differences (at α=0.05) in Jordanian EFL sixth-grade students’ writing performance along the features of ideas, organization, sentence fluency, conventions, and legibility, which may be attributed to instructional modality (conventional vs. PLE-based)?

Significance of the Study

To the best of these researchers’ knowledge, this may be one of the first studies to examine the potential effect of PLE-enhancing tools on EFL writing performance in Jordan. International research has mainly targeted older students, particularly college students (e.g., del Barrio-García et al., 2015; Vance, 2012), and teachers (e.g., Häkkinen & Hämäläinen, 2012; Shaikh & Khoja, 2014) and seldom, if any, participants as young as those of the present research.

Furthermore, that the research aggregates the PLE-enhancing tools of flipped learning, mind mapping, reflection, and technology integration may also add to its significance as this, to the best of these researchers’ knowledge, may be the first time these tools are addressed together in one study. The findings may not only help teachers with innovative tools to promote foreign language writing but also draw attention to this topic for researchers to explore it further. The current findings may spur more research into the effect of PLE-enhancing tools on writing performance and motivation to learn writing.

Method and Procedures

The research uses a quasi-experimental design. with the use of PLE-enhancing tools as the independent variable and writing performance as the dependent variable. Two intact sections out of the four sixth-grade sections at Juffein Primary School for Boys in the Directorate of Education of the Koura District, Irbid (Jordan) were randomly selected and, with a toss of a coin, distributed into an experimental group (n=20), which was instructed using PLE-enhancing tools, and a control group (n=20), which was instructed per the guidelines of the Teacher’s Book of the MOE-prescribed Action pack 6 taught to all six-grade students in the public schools of Jordan.

The content taught to both groups was the same (viz., Units 8, 9, 10, Review 3, 11, 12, 13, 14, and Review 4 in both the Students’ Book and Activity Book), but the delivery was different. All the writing content (mainly activities) covered in the second semester of the Action Pack 6 textbook was redesigned using PLE-enhancing tools to be used with the experimental group but was left as is to be taught per the Teacher’s Book to the control group. Two sets of lesson plans were designed (n= 26 each) to use with the experimental and control groups.

To examine the effect of PLE on the experimental group participants’ writing performance, the researchers redesigned the writing exercises in the Students’ Book and Activity Book of Action Pack 6 using PLE-enhancing tools (viz., flipped learning, mind mapping, reflection, and technology integration). The treatment was implemented in two to three 45-minute sessions a week for ten weeks.

The treatment was designed following a content analysis of the sixth-grade English textbook, Action Pack 6, to identify the number, distribution, and nature of the writing activities in the target units of the textbook(viz., Units 8, 9, 10, Review 3, 11, 12, 13, 14, and Review 4 in both the Students’ Book and Activity Book). Based on the results of the content analysis, the activities were redesigned to align with the principles of PLE using a host of relevant tools (e.g., flipped learning, reflection, mind mapping, technology integration). Twenty-six lesson plans were drafted and given to a 10-member expert jury in linguistics, foreign language education, and measurement and evaluation to assess their appropriateness in terms of content, procedure, and timing. The validation jury’s feedback was used to produce the final version of the instructional treatment.

Right before the treatment, both groups were administered a writing pre-test to set a benchmark and ensure equivalence. A post-test was administered following each treatment to gauge progress and report findings as to the comparative utility. These tests were designed in light of the intended learning outcomes for the writing component in the Teacher’s Book of Action Pack 6 (viz., Units 8, 9, 10, Review 3, 11, 12, 13, 14, and Review 4 in both the Students’ Book and Activity Book). The students of both groups were asked to write a one-paragraph essay on a trip they had taken with their friends or family for the pre-test and on what would they do to protect endangered animals for the post-test.

Both tests were checked for validity by means of a jury of ten experts whose feedback was taken into account in the final version of the test. The reliability of the tests was also established by piloting them to 20 sixth-grade students from another section in the same school with a two-week interval. The Pearson Correlation Coefficients between the two administrations amounted to 0.83 and 0.80 for the pre- and post-tests, respectively, which is deemed appropriate for the purpose of the research (Cronbach & Warrington, 1951).

The participants’ writing performances were assessed using a basic writing rubric adopted from Cox (2020) along five writing features (viz., ideas, organization, sentence fluency, conventions, and legibility), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

The Scoring Rubric

Instructing the Two Groups

Instructing the Experimental Group: The PLE-Based Instructional Treatment

Prior to the commencement of the treatment, a consent letter was sent to each student’s parents outlining the purpose and procedures of the study and seeking their permission for their respective children’s participation. All parents granted consent and were enthusiastic for their children’s participation. Permission was also sought from the consenting parents for their children to bring a smart phone or tablet to school to be used for the research purposes, which was also granted

The experimental group was taught writing using PLE-enhancing tools per the following procedures:

- The teacher/first researcher introduced the concept of PLE, defined its tools, and illustrated its potential utility in learning writing.

- The participants (of the experimental group) watched videos about different PLE-enhancing tools and reflected on how these tools could help improve their own writing performance.

- The teacher/first researcher logged into his account on Kidblog and showed a demo of the platform.

- With the help of the teacher/first researcher, each participant created an account on Kidblog, wrote a post, uploaded a picture/video or more, and shared them.

- The participants sat in groups of four or five (of their choice) in the school library during the writing sessions throughout the ten weeks of the treatment, with each having a smart phone or tablet on hand.

- The participants started to write at the sentence level, advancing gradually to paragraph level with the passage of time and instruction.

- The participants both collaborated and engaged in peer assessment, moving gradually to self-assessment.

- The teacher/first researcher scored each assignment and provided feedback on individual writing performance.

Instructing the Control Group

The control group was taught per the guidelines in the Teacher’s Book of Action Pack 6. No specific instructional guidelines were provided for the writing component, except for the following:

- The teacher/first researcher introduces every writing task by reading the title of the activity, asking questions, and assigning it either as a class task or as homework to be submitted in a later lesson.

- Students write individually as the teacher circulates among them monitoring their work and helping them with punctuation and other writing mechanics.

- The teacher checks students’ work and provides a score (usually out of 10) without comments on the writing piece itself.

- Some students read out their pieces as the teacher encourages praising peers’ work.

Findings

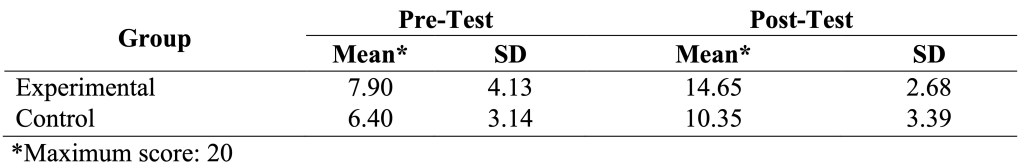

To answer the first question of the research, which seeks to identify potential statistically significant differences (at α=0.05) in Jordanian EFL sixth-grade students’ overall writing performance which may be attributed to the instructional modality, the means and standard deviations of the participants’ pre- and post-test scores were calculated, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Means and Standard Deviations of the Participants’ Overall Pre-/Post-Treatment Writing Performance

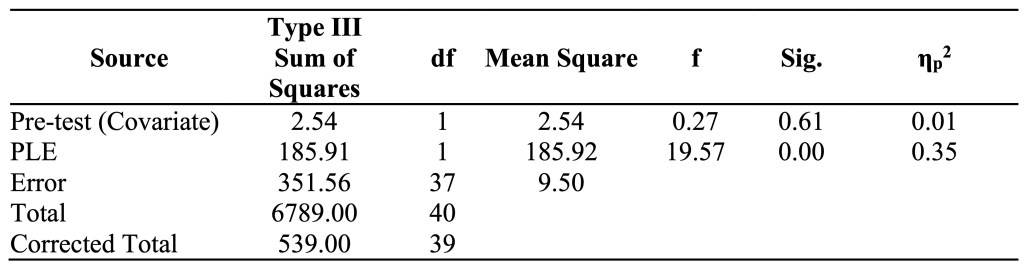

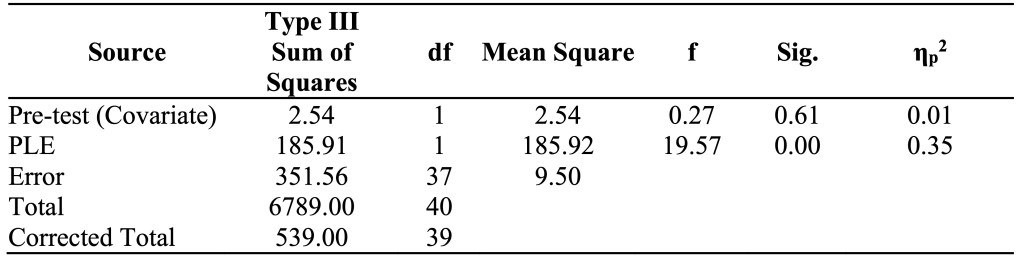

Table 2 shows observed differences in the pre- and post-test overall writing mean scores of the experimental group and the control group (14.65 vs. 10.35). To determine the potential statistical significance of the effect of the PLE-based treatment on the experimental group’s overall writing performance (after controlling for the effect of the pre-test scores), one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3

One-Way ANCOVA of the Effect of PLE on Overall Writing Performance (After Controlling for the Effect of the Pre-Test)

Table 3 shows that, after controlling for the effect of the pre-test, the experimental group outperformed the control group with statistically significant differences between the overall writing performance of the two groups. The partial eta squared score indicates that using PLE accounted for about 35 percent of the variation in overall writing performance. Table 4 shows the means, standard deviations and standard errors of the two groups’ overall writing performances with pre-test scores as a covariate.

Table 4

Unadjusted and Adjusted Group Means and Variability of the Overall Writing Performance (Pre-test Scores as a Covariate)

Table 4 shows that the experimental group participants’ overall writing performance is better than that of their control group counterparts. As such, PLE-based instruction brings about superior overall writing performance to its conventional counterpart.

To answer the second research question, which seeks to identify potential statistically significant differences (at α=0.05) in Jordanian EFL sixth-grade students’ writing performance along the features of ideas, organization, sentence fluency, conventions, and legibility which may be attributed to the instructional modality, the means and standard deviations of the participants’ writing performance in the five features before and after the treatment were calculated, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5

Means and Standard Deviations of the Participants’ Scores on each Writing Feature on the Pre- and Post-Tests

Table 5 shows that, even though the pre-test mean scores of the experimental and control group participants in the five writing features (viz., ideas, organization, sentence fluency, conventions, and legibility) are similar, observed differences are found in the two groups’ participants’ post-test mean scores.

After adjusting for variations in the pre-test scores, a one-way multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) using Hoteling’s Trace test was used to examine the effect of using PLE-based instruction on the linear combination of the five writing features on the post-test, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6

One-Way MANCOVA of the Effect of PLE Instruction-Based on the Post-Test on the Five Writing Feature

Table 6 shows that the differences between the experimental and control groups’ participants’ performance in the five writing features are statistically significant, in favor of the experimental group, as the use of the PLE-based instruction seems to account for just over 38 percent of the variance in the linear combination of the five writing features. A follow-up (between subjects) Univariate Analysis was also used to examine the effect of PLE- based instruction on the participants’ writing performance in the five features, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7

Univariate Analysis of the Five Writing Features (Controlling the Effect of the Pre-Test)

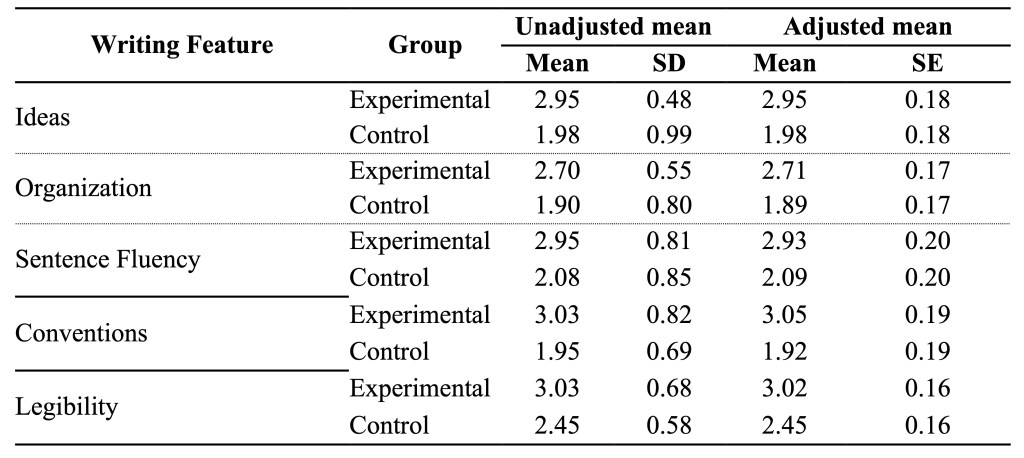

Table 7 shows statistically significant differences between the experimental and the control groups, as the former outperformed the latter in all five features. Table 7 also shows that PLE-based instruction accounted for about 29, 25, 20, 34, and 16 per cent of the variance in the participants’ performance in the features of ideas, organization, sentence fluency, conventions, and legibility, respectively, with the largest effect size showing in the feature of conventions followed by ideas, organization, sentence fluency, and legibility. The means, standard deviations, and standard errors of the two groups’ participants’ writing performance in each of the five features were calculated, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8

Unadjusted and Adjusted Group Means and Variability of the Writing Performance in the Five Features (Pre-Test Scores as a Covariate)

Table 8 shows that the two groups’ participants’ writing performance differed significantly in the five features, in favor of those in the experimental group. As such, PLE-instruction improved the experimental group participants’ writing performance in the five features.

Discussion, Conclusions, and Implications of the Research

The use of the PLE-enhancing tools improved the participants’ writing performance, both overall and along the five features (viz., ideas, organization, sentence fluency, conventions, and legibility). This may have been brought about by the meticulous design and implementation of the treatment and the close attention to detail throughout the ten weeks of the treatment.

Each of the 26 lessons came with a set of clear procedural instructions for both the teacher and the students to carry out the lessons and do the assignments to achieve the objectives of the treatment. For instance, the writing assignments were planned and organized in a manner which not only sparked the participants’ interest but also allowed them ample time to write and rewrite both individually and collaboratively.

That PLE-based instruction promoted both individual and collaborative work on the writing tasks may have also helped the participants grow as writers. The use of PLE-enhancing tools improved participants’ engagement and time-on-task which, in turn, encouraged them to write more. The collaborative features of the treatment also fostered participants’ engagement and time-on-task as less able participants benefitted from their more able counterparts. The participants were allowed opportunities to learn more by actively engaging not only in individual PLE-enhancing tools but also in collaborative activities with their peers rather than just listening to the teacher.

The participants’ increased motivation to write was evident throughout the treatment, especially with the novelty of the PLE-enhancing tools (viz., flipped learning, mind mapping, reflection, technology integration) which not only promoted their ownership but also encouraged them to engage more in the writing activities throughout the treatment. Technology integration was a driving force for participant engagement as they made use of flipped learning, YouTube and other authentic resources which catalyzed writing performance through the provision of content used to create sentences and paragraphs.

The emphasis on the learner throughout the instructional treatment may also have contributed to the experimental group’s participants’ improved performance over that of the control group. The ad hoc assignment of topics as end-of-class or homework tasks typical of the conventional writing classroom is replaced with planned rituals which comprise planning, writing, revising and reviewing both individually and with peers up to the final piece of writing. Prior to starting the actual writing task, using PLE-enhancing tools (e.g., flipped learning, mind mapping, reflection, technology integration) helped the participants successfully prepare, collect their thoughts, brainstorm, and organize ideas, which ultimately improved their writing performance.

Following the PLE-based treatment, the participants’ writing performance improved both overall and in the five writing features (viz., ideas, organization, sentence fluency, conventions, and legibility), more so than did the conventional teacher book-based treatment of the control group. The participants’ engagement and time-on-task were also fostered as they actively engaged in the activities of the instructional treatment. The participants experienced the shift from traditional teacher-centered instruction to more independent learning that not only incorporated new strategies but also met their individual needs.

Both the experimental and the control groups were exposed to the same content (viz., Action Pack 6), but the instructional delivery was different. However, that the experimental group participants outperformed their control group counterparts is evidence for the effectiveness of PLE-based instruction in promoting the instructional content of the textbook and the teaching/ learning process.

Of the pedagogical implications of the current findings is the need for affording foreign language writing, the otherwise neglected skill (e.g., Harder, 2006; Moon, 2008; Obeiah & Bataineh, 2016), due attention and allowing learners opportunities for classroom practice using various PLE-enhancing tools (e.g., flipped learning, mind mapping, reflection, technology integration). Towards this end, EFL teachers my need to reconsider the tools and strategies they use in the writing classroom to promote ownership and independent learning.

Availing learners with interactive writing strategies may not only enhance their writing performance but also make writing less daunting. Learners are often reluctant to engage in writing because they do not find it personally relevant or interesting enough, not to mention the technical difficulties associated with functional literacy (e.g. spelling, grammar, mechanics) which increases the pressure to produce coherent text.

PLE-enhancing tools may constitute potential catalysts for a more effective writing instruction in the foreign language classroom, especially when coupled with well thought-out technology integration. Learners and teachers alike may reap the fruits of this integration as writing improves without the hassles and resistance reported of writers of all ages. Together, they may encourage learners to write regularly, share their writing, and overcome individual challenges, which, in turn, would create a culture of writing in the foreign language classroom in which both learners and teachers may thrive.

Limitations and Recommendations for Further Research

Even though the current research, which is essentially exploratory in nature, is sound in method and procedure, the generalizability of its findings may be constrained by the sample size and selection process. The research only targeted a convenient sample of male sixth-grade students, but a mixed-gender pool of participants may have added insights and enhanced the generalizability of the findings. In addition, addressing only four PLE-enhancing tools (viz., flipped learning, mind mapping, reflection, and technology integration) may have also limited the generalizability of the findings as the use of other tools may potentially affect the findings.

Future researchers are called upon to extend the scope of research not only to other grade levels in school and tertiary education but also to other language skills. Examining the potential improvements brought about by PLE-enhanced tools on listening, speaking, and writing will not only fill a gap in the literature on foreign language education but will also support the present findings with further empirical evidence.

References

Abdelrahman, L., DeWitt, D., Alias, N., & Rahman, M. (2017). Flipped learning for ESL writing in a Sudanese school. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 16(3), 60–70.

Adell, S. J., & Castañeda Quintero, L. (2010). Personal learning environments (PLEs): A new way of understanding learning. In R. Roig Vila & M. Fiorucci (Eds.), Keys to research in educational innovation and quality. The integration of information and communication technologies and interculturality in the classroom. L’Università degli Studi Roma Tre. http://hdl.handle.net/10201/17247

Ahmad, M.A.E.A.S.A. (2016). The effect of a flipping classroom on writing skill in English as a foreign language and student’s attitude towards flipping. US-China Foreign Language, 14(2), 98–114. https://doi.org/.10.17265/1539-8080/2016.02.003

Al-Hamad, R. F., Al-Jamal, D. A., & Bataineh, R. F. (2019). The effect of MALL instruction on teens’ writing performance. Digital Education Review, 35, 289–298. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1220122.pdf

Al-Zyoud, A., Al-Jamal, D., & Baniabdelrahman, A. (2017). Mind mapping and students’ writing performance. Arab World English Journal, 8(4), 280–291. https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol8no4.19

Anggraeni, N., & Yasa, N. (2012). E-Service quality Terhadap Kepuasan dan Loyalitas Pelanggan Dalam Penggunaan Internet banking. Journal Keuangan dan Perbankan, 16(2), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.26905/jkdp.v16i2.1072

Attwell, G. (2007). Personal learning environment- The future of learning? eLearning Papers, 2(1), 1–8. https://www.sciepub.com/reference/131009

Bani Younis, R., & Bataineh, R.F. (2016). To dictogloss or not to dictogloss: Potential effects on Jordanian EFL learners’ writing performance. Apples- Journal of Applied Language Studies, 10(2), 45–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.17011/apples/urn. 201610114330

Bartolomé, A., & Cebrian-de-la-Serna, M. (2017). Personal learning environments: A study among higher education students’ designs. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology, 13(2), 21–41. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1153337.pdf

Bataineh, R. F., & Al-Majali, H. A. (2023). Do Mind maps really catalyze EFL grammar learning? Conjunction as a case. International Journal of Language Education, 7(4), 633–645. https://doi.org/10.26858/ijole.v7i4.36393

Bataineh, R. F., & Alqatanani, A. K. (2019). How effective is Thinking Maps® instruction in improving Jordanian EFL learners’ creative reading skills? TESOL Journal, 10:e00360(First Published Online: 20 December 2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.360

Bataineh, R. F., & Bani Younis, R. (2016). The effect of dictogloss on Jordanian EFL teachers’ instructional practices and students’ writing performance. International Journal of Education and Training, 2(1), 1–11. http://www.injet.upm.edu.my/

Bataineh, R. F., & Obeiah, S. F. (2016). The effect of scaffolding and portfolio assessment on Jordanian EFL learners’ writing. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 6(1), 12–19. http://dx.doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v6i1.2643

Bataineh, R. F., & Salah, N. A. (2017). The effectiveness of drama-based instruction in Jordanian EFL students’ writing performance. TESOL International Journal, 12(2), 103–118. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1247797.pdf.

Boling, E., Castek, J., Zawilinski, L., Barton, K., & Nierlich, T. (2008). Collaborative literacy: Blogs and internet projects. The Reading Teacher, 61(6), 504–506. https://www.learntec hlib.org/p/102315/

Brown, S. (2010). From VLEs to learning webs: The implications of Web 2.0 for learning and teaching. Interactive Learning Environments, 18(1), 1–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ 10494820802158983

Chai, A., & Hamid, A. (2023). The impact of flipped learning on students’ narrative writing. International Journal of Advanced Research in Education and Society, 4(4), 159–175.

Cox, J. (2020). Writing rubrics. ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/writing-rubric-2081370

Cronbach, L., & Warrington, W. (1951). Time-limit tests: Estimating their reliability and degree of speeding. Psychometrika, 16(2), 167–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289113

Dabbagh, N., & Kitsantas, A. (2012). Personal learning environments, social media, and self-regulated learning: A natural formula for connecting formal and informal learning. The Internet and Higher Education, 15(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc. 2011.06.00

Davies, G., Walker, R., Rendall, H., & Hewer, S. (2011). Introduction to computer assisted language learning (CALL). Module 1.4. In G. Davies (Ed.), Information and communications technology for language teachers (ICT4LT). http://www.ict4lt.org/en/ en_mod1-4.htm

del Barrio-García, S., Arquero, J.L., & Romero-Frías, E. (2015). Personal learning environments acceptance model: The role of need for cognition, e-learning satisfaction and students’ perceptions. Journal of Educational Technology and Society, 18(3), 129–141.

Ekmekci, E. (2017). The flipped writing classroom in Turkish EFL context: A comparative study on a new model. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 18(2), 151–167.

Faridha, N. (2019). The effect of video in teaching writing skill across different personality. Journal of English Educators Society, 4(1), 61–65. https://doi.org/10.21070/jees.v4i1.1808

Graham, S., Harris, K., & MacArthur, C.A. (1993). Improving the writing of students with learning problems: Self-regulated strategy development. School Psychology Review, 22(4), 656–670. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ486059

Häkkinen, P., & Hämäläinen, R. (2012). Shared and personal learning spaces: Challenges for pedagogical design. The Internet and Higher Education, 15(4), 231–236. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.09.001

Harder, A. (2006). The neglected life skill. Journal of Extension, 44(1). https://tigerprints. clemson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4375&context=joe

Harmelen, M. (2006). Personal learning environments. Proceedings of the Sixth IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (pp. 815–816). https://wiki.ties.k12.mn.us/file/view/PLEs_draft.pdf/282847312/PLEs_draft.pdf

Harmelen, M. (2008). Design trajectories: Four experiments in PLE implementation. Interactive Learning Environments, 16(1), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820701772686

Herder, A., Berenst, J., de Glopper, K., & Koole, T. (2018). Reflective practices in collaborative writing of primary school students. International Journal of Educational Research, 90, 160–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2018.06.004

Keshta, A., & Harb, I. (2013). The effectiveness of a blended learning program on developing Palestinian tenth graders’ English writing skills. Education Journal, 2(6), 208–221. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.edu.20130206.12

Klein, A. (2012). What is the impact of blogging used with self-monitoring strategies for adolescents who struggle with writing? Unpublished Masters’ Thesis. University of Wisconsin at River Falls.

Milligan, C., Beauvoir, P., Johnson, M., Sharples, P., Wilson, S., & Liber, O. (2006). Developing a reference model to describe the personal learning environment. In W. Nejdl & K. Tochtermann, (Eds.), Lecture notes in computer science (pp. 506–511). Springer.

Moon, J. (2008). L2 children and writing: A neglected skill? ELT Journal, 62(4), 398–400. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccn039

Myhill, D. (2009). Children’s patterns of composition and their reflections on their composing processes. British Educational Research Journal, 35(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920802042978

Noytim, U. (2010). Weblogs enhancing EFL students’ English language learning. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 1127–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010. 03.159

Nunan, D. (1999). Second language teaching and learning. Heinle & Heinle.

Obeiah, S. F., & Bataineh, R. F. (2016). The effect of portfolio-based assessment on Jordanian EFL learners’ writing performance. Bellaterra Journal of Teaching and Learning Language & Literature, 9(1), 32–46. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/jtl3.629

Olshtain, E. (2001). Functional tasks for mastering the mechanics of writing and going just beyond. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language (pp. 207–217). Heinle & Heinle.

Özdemir, E., & Aydın, S. (2015). The effects of blogging on EFL writing achievement. Procedia-social and Behavioral Sciences, 199, 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.521

Pradasari, N. I., & Pratiwi, I. (2018). Mind mapping to enhance students’ writing performance. Linguistics, Literature and English Teaching Journal, 8(2), 130–140. https://jurnal.uin-antasari.ac.id/index.php

Reinders, H. (2014). Personal learning environments for supporting out-of-class language learning. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1050245.pdf

Schaffert, S., & Hilzensauer, W. (2008). On the way towards personal learning environments: Seven crucial aspects. eLearning Papers, 9(2), 1–11. http://matchsz.inf.elte.hu/tt/docs/ media15971.pdf

Severance, C., Hardin, J., & Whyte, A. (2008). The coming functionality mash-up in personal learning environments. Interactive Learning Environments, 16(1), 47–62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10494820701772694

Shah, C., Erhard, K., Ortheil, H., Kaza, E., Kessler, C., & Lotze, M. (2013). Neural correlates of creative writing: An fMRI study. Human Brain Mapping, 34(5), 1088–1101. https://doi. org/10.1002/hbm.21493

Shaikh, Z.A., & Khoja, S.A. (2014). Personal learning environments and university teacher roles explored using Delphi. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 30(2), 202–226. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.324

Sokolik, M. (2003). Writing. In D. Nunan (Ed.). Practical English language teaching (pp. 87-108). McGraw-Hill.

Soliman, M. (2021). The effectiveness of using mind mapping strategy in developing writing skills for sixth year primary school students in Qatar. International Journal of Humanities and Educational Research, 3(4), 206–220. http://dx.doi.org/10.47832/2757-5403.4-3.4

Styati, E. (2016). Effect of YouTube videos and pictures on EFL students’ writing performance. Dinamika Ilmu, 16(2), 307–317.

Sykes, J., Oskoz, A., & Thorne, S.L. (2008). Web 2.0, synthetic immersive environments, and mobile resources for language education. CALICO Journal, 25(3), 528–546. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.v25i3.528-546

Taraghi, B., Ebner, M., & Schaffert, S. (2009). Personal learning environments for higher education: A mashup-based widget concept. Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Mash-Up Personal Learning Environments (pp.15–22). https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-506/taraghi.pdf

Ullrich, C., Borau, K., Luo, H., Tan, X., Shen, L., Shen, R. (2008). Why Web 2.0 is good for learning and for research: Principles and prototypes. Proceedings of the 17th International World Wide Web Conference (pp. 705–714). Association for Computing Machinery.

Vance, L. K. (2012). Do students want Web 2.0? An investigation into student instructional preferences. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 47(4), 481–493.

https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.47.4.g

Vass, E., Littleton, K., Miell, D., & Jones, A. (2008). The discourse of collaborative creative writing: Peer collaboration as a context for mutual inspiration. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 3(3), 192–202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2008.09.001

Wilson, S. (2008). Patterns of personal learning environments. Interactive Learning Environments, 16(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820701772660

Yawiloeng, R. (2022). Using mind-mapping to develop EFL students’ writing. SSRN. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4258092.

Zhou, H. (2013). Understanding personal learning environment: A literature review on elements of the concept. Proceedings of the Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education International Conference (pp.1161–1164). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/48278/