Pınar Üstündağ-Algın, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Ankara, Türkiye. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2595-6570

Hatice Karaaslan, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Ankara, Türkiye. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7632-3795

Nurseven Kılıç, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Ankara, Türkiye. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8724-7564

Üstündağ-Algın, P., Karaaslan, H., & Kılıç, N. (2025). Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(3), 566–590. https://doi.org/10.37237/160305

Abstract

Learner autonomy has long been recognized as a cornerstone of successful second language (L2) instruction; however, the connection between instructors’ workplace well-being (WWB) and autonomy-supportive teaching has been little explored. Guided by the PRISM framework (Kellerman & Seligman, 2023), this study draws on interviews with 11 higher education L2 instructors from four countries to examine how Prospection, Resilience, Innovation, Social Support, and Mattering shape autonomy-supportive teaching beyond the classroom. Prospective instructors more readily adapt to changing circumstances, designing flexible out-of-class learning activities. Resilientinstructors employ emotional regulation andcognitive agility to manage workload pressures, while those with an innovative mindset embrace divergent thinking and iterative learningstrategies, often adopting new technologies, especially when backed by social support from colleagues and administrators. A clear sense of mattering kept instructors motivated to pursue student-centered learning beyond class. These findings suggest that strong WWB supports L2 instructors’ job satisfaction and strengthens their commitment to promoting learner autonomy. These findings carry important implications for educational leaders and policy makers, suggesting that targeted professional development and institutional frameworks aligned with the PRISM Model can create supportive, autonomy-friendlyenvironmentswhere both instructors and learners thrive.

Keywords: Workplace Well-Being, PRISM Model, Learner Autonomy, L2 Instruction, Autonomy-Supportive Teaching

“Teachers: The new generation will be your masterpiece.” – Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, 1924

In language education, fostering learner autonomy, in which students take responsibility for their own learning, is widely recognized as essential (Benson, 2013; Little, 1991). Autonomous learners tend to be more motivated and sustain engagement with language resources beyond classroom instruction (Borg & Al-Busaidi, 2012; Karaaslan & Kılıç, 2019). Nevertheless, constraints related to class time and curricula often limit opportunities for independent learning (Richards, 2015). In response, promoting beyond-the-classroom engagement through self-access resources and autonomy-supportive instruction has become a cornerstone of L2 pedagogy (Reinders & White, 2016).

While learner autonomy and the availability of self-access resources are well established, the instructor’s role remains pivotal for guiding and sustaining these practices (Gardner & Miller, 1999). Instructors do more than provide resources; they shape the learning environment through their attitudes and pedagogical choices, as well as the degree of institutional support available to them. This raises an important yet underexplored question: How does L2 instructors’ workplace well-being (WWB) influence their willingness to adopt autonomy-supportive practices? Although we know much about how to cultivate learner autonomy, relatively little attention has been given to how instructors’ WWB may affect their commitment to promoting independent learning beyond the classroom.

A substantial body of research shows that educators with greater professional autonomy are more likely to foster autonomy in their learners (Benson, 2013; Lamb, 2008). However, much of this literature gives limited consideration to how teachers’ autonomy is continuously shaped by broader institutional and psychological forces. Studies have linked leadership style, job satisfaction, stress, burnout, and professional support to educators’ sense of autonomy (Ingersoll, 2003; Pearson & Moomaw, 2005; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2014), yet the specific connection between WWB and autonomy-supportive practice remains largely unexplored.

We argue that a supportive work environment that addresses instructors’ psychological and professional needs is a prerequisite for sustaining autonomy-oriented teaching and for promoting self-directed learning beyond the classroom. Building on this perspective, we adopt the PRISM Model (Kellerman & Seligman, 2023) as a theoretical framework to examine how L2 instructors’ WWB shapes their capacity to create and maintain autonomy-supportive environments and to foster effective self-access learning practices.

The PRISM Model

In today’s “whitewater world of work,” a term coined by Brown (2015) to describe the unpredictable currents of modern workplaces, successfully navigating continuous change and seizing emerging opportunities requires workplace-specific psychological capacities. While the PERMA model (Karaaslan, 2019; Seligman, 2011) provides a foundation for understanding well-being, adapting it to the complexities of modern professional environments requires a broader framework that accounts for the psychological and institutional factors influencing workplace thriving. Responding to this need, the PRISM model (Kellerman & Seligman, 2023) extends PERMA by integrating key psychological capacities essential for thriving amid workplace uncertainty. The PRISM (an acronym for Prospection, Resilience, Innovation, Social Support, and Mattering) offers a comprehensive framework for understanding the core dimensions of WWB.

Prospection: Navigating Uncertainty

Unlike the relatively predictable and repetitive tasks of the Industrial Revolution, today’s digital-era workplaces demand that professionals anticipate multiple possible outcomes, adapt plans in real time, and proactively shape their career paths (O’Reilly et al., 2018). In an era of this rapid change, prospectionenables individuals to imagine possible outcomes, set realistic goals, design structured plans, and execute them with a focus on opportunities rather than setbacks (Kellerman & Seligman,2023). Pragmatic Prospection Theory (Baumeister et al., 2016), which treats future-oriented thinking as a practical tool for guiding present action, aligns with the PRISM model’s prospection subdimensions: Imagining Outcomes, Setting Sensible Goals, Making a Plan, and Flexible Execution (i.e., carrying out a plan adaptively by monitoring progress and revising tactics when conditions change). This perspective provides a structured lens for understanding how prospection supports WWB across diverse professional contexts.

Resilience: Building Antifragility

In the PRISM Model, resilience extends beyond bouncing back from adversity to include adaptive growth, where challenges create opportunities. It is structured around five sub-dimensions: Emotional Regulation, Optimism, Cognitive Agility (i.e., the capacity to adjust mental sets and strategies in real time—balancing exploratory openness and focused execution as conditions change; Good & Yeganeh, 2012), Self-Compassion, and Self-Efficacy (Kellerman & Seligman, 2023). Individuals who cultivate resilience tend to recover more effectively from hardships and develop an antifragile mindset (Taleb, 2012), enabling them to thrive in unpredictable work environments. In L2 education, instructors’ resilience and WWB are essential for fostering positive teaching experiences and managing professional stressors, both of which enhance teaching outcomes (Ding et al., 2024; Zhang, 2023). Empirical findings further suggest that structured in-school interventions play a critical role in reducing negative consequences and fostering resilient capacities in learners (Yılmaz-Dinç & Kılıç, 2025).

Innovation: Forging the Future

Within the PRISM Model, innovation functions as a WWB resource when instructors have the knowledge, beliefs, and support to redesign learning rather than merely digitize it. Recent syntheses indicate that coherent technological–pedagogical–content integration supports purposeful task redesign, a foundation for autonomy-supportive work (Fontyn et al., 2025). Innovation also depends on autonomy-supportive climates. Evidence with novice educators shows that perceived autonomy support relates to higher innovative work behaviour, suggesting that trusting organizational conditions energize experimentation and iterative improvement (Lin & Liu, 2025). Collaborative, ongoing professional learning further strengthens this capacity; systematic reviews show that well-designed CPD (coaching, collaboration, practice-embedded feedback) improves instructional quality and, in turn, student outcomes (Ventista & Brown, 2023). In L2 contexts, pedagogical innovations such as digital multimodal composing expand feedback, agency, and choice, supporting learner autonomy while giving instructors data for rapid iteration (Karaaslan & Çolak, 2024; Xie & Jiang, 2025).

Social Support: Cementing Connections

As emphasized in the PRISM Model, social support in the workplace enables individuals to thrive rather than merely survive (Kellerman & Seligman, 2023). This, in turn, reinforces a sense of connection and shared purpose, helping individuals feel more secure and less lonely (Reece, Carr et al., 2021). In school settings, perceived organizational support is associated with higher work engagement and WWB among educators, indicating that administrative backing protects energy for pedagogy beyond the classroom (Wang, 2024). Complementing this, evidence with rural educators shows that social support predicts work engagement, with individual self-regulatory capacities shaping the pathway, underscoring how supportive contexts translate into day-to-day motivation (Wu et al., 2025). At a broader level, large-scale syntheses link supportive interpersonal climates, marked by collegial trust and respectful communication, to better learning, performance, and health outcomes, clarifying how constructive interaction reduces strain and enables adaptive teaching (Dong et al., 2024). Finally, professional learning gains traction when embedded in supportive contexts (e.g., coaching, modeling, and feedback loops), suggesting that social support both buffers stress and facilitates the uptake of autonomy-supportive practices (Reeve & Cheon, 2024). In practical terms, expressions of care and esteem, and timely advice and feedback, together with a felt sense of belonging and mutual exchange, work in concert to sustain educators’ capacity to foster learner autonomy in and beyond the classroom.

Mattering: Leaving Impact

Mattering is central to WWB, fostering motivation and engagement when individuals feel valued and recognized (Kellerman & Seligman, 2023). Within the PRISM Model, mattering is specified as organizational mattering, defined as the perception that one’s work has impact and is noticed by the professional community; this includes recognition and achievement facets, which are associated with outcomes such as job satisfaction and retention (Reece, Yaden et al., 2021). For educators, feeling both impactful and seen is linked to higher work engagement and to the psychological resources needed to plan, iterate, and follow through on complex instructional practices, consistent with resource-based views of motivation (Kurtessis et al., 2017). By contrast, anti-mattering (feeling invisible) relates to distress and loneliness, underscoring the risks when recognition is absent (Flett et al., 2022; McComb et al., 2020). Organizational cues that convey value, such as fairness, supervisor support, and constructive rewards, are strong predictors of perceived organizational support and are associated with stronger engagement and performance (Kurtessis et al., 2017). In turn, such resource-rich conditions are associated with the adaptation and maintenance of autonomy-supportive teaching (e.g., perspective taking, interest/value support, reduced control), as indicated by research evidence (Cheon et al., 2023; Reeve & Cheon, 2021; 2024).

PRISM-Guided Proposition and Research Question

In the L2 teaching context, we propose that instructors’ capacity to foster learner autonomy beyond the classroom is jointly enabled by prospection, resilience, innovation, social support, and mattering. A prospective mindset can help instructors anticipate learners’ needs, integrate new resources, and adapt to evolving technologies, yielding structured yet flexible experiences that scaffold autonomy. Resilience can enable instructors to navigate heavy workloads, curriculum changes, and institutional shifts while maintaining WWB and continuing to design autonomy-supportive learning. An innovation mindset (for example, developing digital modules, implementing AI-assisted learning, or designing flexible curricula) can support the personalization and continual improvement that such environments require. Social support can strengthen instructors’ ability to sustain autonomy-supportive practices by promoting a collaborative and encouraging work environment, with concrete mechanisms including peer collaboration, administrative encouragement, and institutional backing, which are linked to work engagement among instructors (Fan et al., 2024). Finally, mattering can enhance instructors’ capacity to create and sustain autonomy-supportive teaching by reinforcing their sense of significance within their professional community (Derakhshan et al., 2024). When instructors feel that their contributions are valued and have meaningful impact on their workplace and learners, they are more likely to engage in practices that promote learner autonomy and extend learning beyond the classroom.

Building on the PRISM Model (Kellerman & Seligman, 2023), this study investigates how L2 instructors’ WWB influences their capacity to foster learner autonomy and promote self-access learning beyond the classroom. Accordingly, our research question is: How do L2 instructors in higher education experience WWB as conceptualized by the PRISM Model, and how does it shape their ability to foster learner autonomy and self-access learning beyond the classroom?

Methodology

Context and Participants

This study draws on semi-structured interviews with eleven second language (L2) higher education instructors from four different countries. Interviews were conducted via Zoom in 2024 due to distance and scheduling issues. Although the data originated from four different countries (Northern Cyprus, Japan, Germany, and Türkiye), cross-national comparisons were beyond the scope of this study, as it was not designed with a comparative focus. We concluded data collection with eleven participants, as no new themes or insights were emerging, indicating data saturation (Guest et al., 2006). Using purposeful sampling (Patton, 2002), participants were L2 instructors in higher education who had completed or were pursuing doctoral degrees in L2 education or related fields, ensuring advanced training and experience to elicit more nuanced, in-depth insights (Creswell, 2013). Following ethical approval, L2 instructors were contacted via email with information about the study’s purpose and participation requirements. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. Each interview lasted about 45 minutes and was transcribed verbatim. Table 1 presents additional demographic information about the participants.

Table 1

Demographic Information of L2 Instructor Participants (N = 11)

Note. All participants are full-time L2 instructors in higher education

Designing the PRISM-Based Interview Questions

The semi-structured interview protocol was developed in multiple stages to ensure validity and alignment with the PRISM Model (Kellerman & Seligman, 2023). Three researchers (the authors) independently drafted initial questions, which were then refined for clarity and coherence. Expert feedback from Dr. Andrew Reece, a founding member of BetterUp Labs (2025), the interdisciplinary research arm of BetterUp whose multi-year studies underpinned the PRISM Model, further enhanced the final set of ten questions, balancing theory with practical relevance. The PRISM Model provided a structured framework for examining L2 instructors’ WWB across five key dimensions: Prospection, Resilience, Innovation, Social Support, and Mattering.

To aid interpretability, the semi-structured interview opened with brief background items (e.g., current role) and then moved through PRISM-aligned sections, each with one concise exemplar: Prospection—“How do you plan for student autonomy and adjust when conditions change?”; Resilience—“When plans falter, how do you adapt your approach?”; Innovation—“What new idea or tool did you test recently, and how?”; Social Support—“Whose support most enables your teaching, and in what ways?”; Mattering—“Can you recall a moment when your work clearly made a difference?”. Follow-ups elicited concrete examples, enablers or barriers, and reflections on WWB.

Data Analysis

The qualitative data were analyzed in three stages: thematic coding, content analysis, and iterative refinement, each building on the previous one. That was done to ensure depth and rigor.

Thematic Coding and Sub-Dimensions

Before analyzing the interview data, each researcher independently coded Chapters 4–9 of Tomorrowmind (Kellerman & Seligman, 2023) in order to make sure we all understood the PRISM model and to find themes serving as sub-dimensions for each PRISM component. We used Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis, following six phases: (1) familiarization; (2) initial coding; (3) theme searching; (4) theme review; (5) theme definition and naming; and (6) reporting. Consensus on Prospection and Resilience was quickly achieved. These subdimensions were particularly salient, whereas the broader scope of Innovation, Social Support, and Mattering required multiple rounds of recoding. In the final stage, Large Language Model (LLM)-generated coding was incorporated to cross-validate and finalize the thematic structure. This process defined sub-dimensions within each PRISM domain, providing a structured framework for qualitative analysis.

Content Analysis

The qualitative data from semi-structured interviews was compiled and analyzed through a systematic process: organizing, coding within predefined sub-dimensions, identifying findings, interpreting results, and validating accuracy (Creswell, 2012). These sub-dimensions ensured that emerging codes remained data-driven and aligned with the PRISM Model dimensions.

Valence Coding

An additional coding cycle assigned positive and negative valences to participant responses within predefined sub-dimensions, capturing attitudinal variations (Saldana, 2016). This iterative process refined the content analysis and deepened insights into nuances across PRISM dimensions. Inter-rater reliability was established through blind reviews, with researchers independently analyzing and comparing categorizations to reach consensus. In cases of disagreement, transcripts were revisited to ensure quotations remained contextualized and accurately categorized. This structured process strengthened the validity and reliability of the findings, with WWB across the PRISM dimensions emerging clearly in the Findings section.

Findings

Our thematic analysis of Tomorrowmind (Kellerman & Seligman, 2023) showed that two PRISM dimensions, Prospection and Resilience, mapped cleanly onto the sub-dimensions reported in the book (Prospection: Imagining Outcomes, Setting Sensible Goals, Making a Plan, Flexible Execution; Resilience: Emotional Regulation, Optimism, Cognitive Agility, Self-Compassion, Self-Efficacy). For the remaining dimensions, Innovation, Social Support, and Mattering, we operationalized sub-dimensions from the same analysis. Innovation comprised Divergent Thinking, Experimentation and Risk Taking, Collaborative Ideation, Iterative Learning (learning through cycles of testing, feedback, and refinement, with updates to tactics and, when needed, underlying assumptions; Kolb, 2014), and Implementation and Impact. Social Support included Emotional Support, Instrumental Support, Informational Support, Belonging and Inclusion, and Reciprocity and Mutual Growth (mutual giving and receiving that foster shared learning and improvement; Cangialosi et al., 2023). Mattering was specified as Sense of Significance, Social Recognition, Meaningful Impact, Reciprocal Connection (mutual exchange of support, recognition, and influence that reinforces belonging and interdependence; Flett, 2022), and Personal Alignment and Ownership (perceived fit between one’s values and strengths and role demands, coupled with a felt responsibility for outcomes and proactive, responsible follow through on tasks; Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). To aid interpretation, we report the results in five tables, each aligned with a PRISM dimension, summarizing key sub-dimensions, sample statements reflecting recurring codes, and attitudinal orientations identified through iterative coding. To maintain confidentiality, quotations are presented briefly with numeric participant codes.

Prospection

Table 2 summarizes L2 instructors’ attitudes toward prospection. Instructors with strong prospection actively plan for autonomy-supportive teaching by envisioning self-access learning benefits (e.g., T2, T4) and adapting to digital tools (e.g., T2, T8). They set flexible goals (e.g., T2, T9), integrate structured plans (e.g., T8, T9), and adjust strategies to maintain engagement (e.g., T8). Their flexibility (e.g., T8, T9) helps them navigate institutional challenges. In contrast, some instructors struggle with uncertainty, making it hard to see self-access learning’s impact (e.g., T1, T3). Administrative burdens (e.g., T1, T3) and curriculum constraints (e.g., T5, T6) hinder goal setting. Without institutional support, autonomy initiatives falter (e.g., T6, T7), and rigid curricula limit flexible execution (e.g., T5, T7), restricting efforts to foster learner autonomy.

Table 2

Participant Statements on Prospection

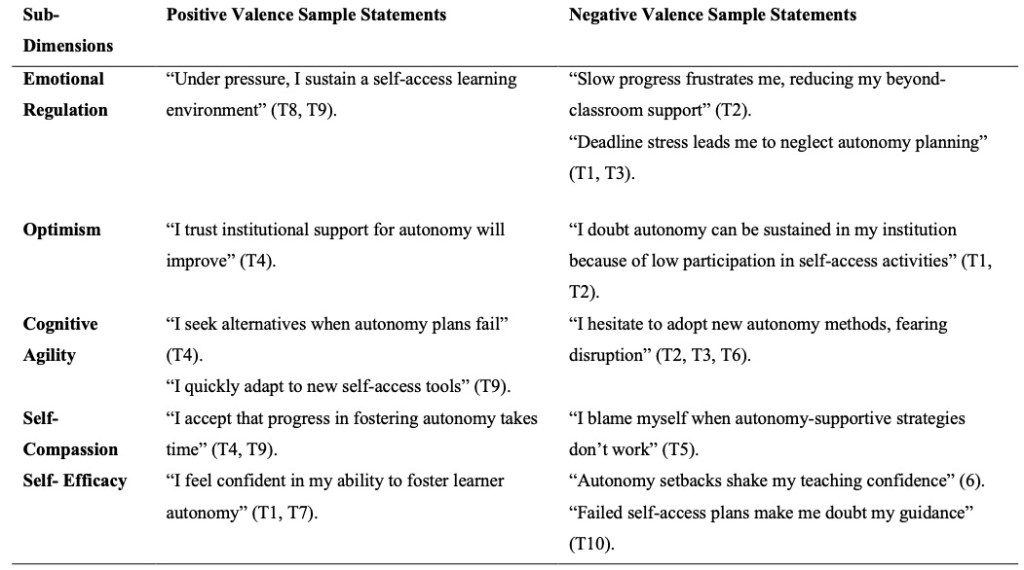

Resilience

Table 3 presents L2 instructors’ perspectives and contrasting experiences on resilience, highlighting both positive and negative valences. Instructors apply emotional regulation, optimism, cognitive agility, self-compassion, and self-efficacy to sustain autonomy-supportive teaching. Some stay composed under pressure (e.g., T8, T9), trust institutional support (e.g., T4), and adjust when autonomy-supportive strategies fail (e.g., T4, T9). They explore alternatives (e.g., T4), respond to challenges with patience (e.g., T4, T9), and remain confident in promoting learner autonomy (e.g., T1, T7). However, some struggle with emotional regulation, feeling frustrated by slow progress (e.g., T2) or stressed by deadlines (e.g., T1, T3). Low optimism is reflected in doubts about sustaining learner autonomy (e.g., T1, T2). Limited cognitive agility leads to hesitation in adopting new methods (e.g., T2, T3). Self-criticism under stress (e.g., T5) and loss of confidence after setbacks (e.g., T6, T10) further challenge their resilience.

Table 3

Participant Statements on Resilience

Innovation

Table 4 presents L2 instructors’ perspectives on and differing experiences with innovation. They apply divergent thinking, experimentation, collaboration, iterative learning, and implementation to foster creativity in autonomy-supportive teaching. Some generate solutions when institutional constraints limit flexibility (e.g., T9, T11), take risks by trying new methods (e.g., T9), and refine self-access strategies based on student needs (e.g., T8, T9). Collaborating with peers to enhance teaching (e.g., T9) and improving digital tools for self-directed learning (e.g., T9) further strengthen their innovative practices. However, some instructors face barriers to innovation, struggling to generate new ideas due to institutional constraints (e.g., T3, T5) and hesitating to take risks unless success is guaranteed (e.g., T3, T4). Collaboration is limited as a lack of institutional support discourages collective efforts (e.g., T5, T6). Challenges in iterative learning arise when structured feedback mechanisms are missing, preventing improvement in autonomy-supportive teaching (e.g., T5, T6). Additionally, implementation remains a hurdle, with some instructors rarely assessing the long-term impact of self-access learning (e.g., T5, T6).

Table 4.

Participant Statements on Innovation

Social Support

Table 5 provides an overview of L2 instructors’ attitudes toward social support in the workplace. Instructors who foster social support create safe spaces for discussions (e.g., T9), assist overwhelmed colleagues (e.g., T4), and share knowledge to help others avoid mistakes (e.g., T9). They view teamwork as a learning process (e.g., T10) and respect diverse perspectives (e.g., T9), reinforcing workplace connections. However, some instructors struggle with a lack of emotional support, making it difficult to sustain motivation for autonomy-supportive teaching (e.g., T5, T6). Others experience limited institutional backing, which hinders their ability to sustain autonomy-supportive practices (e.g., T6, T7). Competitive work environments also restrict mentorship opportunities, making it harder for instructors to identify best practices in autonomy-supportive teaching (e.g., T7, T8). Additionally, when financial security outweighs collaboration, maintaining autonomy-supportive practices becomes more challenging (e.g., T5).

Table 5

Participant Statements on Social Support

Mattering

Table 6 summarizes L2 instructors’ attitudes toward mattering in the workplace. Instructors who feel a strong sense of mattering acknowledge that their institution recognizes their role in fostering student autonomy (e.g., T11), receive appreciation from colleagues (e.g., T4), and see direct evidence of their impact through students’ use of self-access learning (e.g., T10). They also engage in knowledge exchange, strengthening their role in autonomy-supportive teaching (e.g., T9), and find job satisfaction in teaching how to be an autonomous learner (e.g., T11). However, some instructors struggle with feeling valued, perceiving themselves as replaceable and disconnected from learner autonomy efforts (e.g., T5, T8). A lack of recognition makes their contributions feel invisible (e.g., T5, T7), while students’ disengagement with autonomy-supportive strategies leads to feelings of ineffectiveness (e.g., T6, T8). Limited professional exchanges weaken their ability to sustain autonomy-supportive teaching (e.g., T8), and institutional constraints restrict their role in fostering learning beyond the classroom (e.g., T5).

Table 6

Participant Statements on Mattering

Discussion and Conclusion

Our qualitative findings suggest that L2 instructors’ WWB, as framed by the PRISM model, closely relates to their capacity to foster learner autonomy beyond the classroom. Regarding prospection, instructors who actively envision the outcomes of self-access learning tend to adopt more flexible, autonomy-supportive practices, aligning with Henry and Thorsen’s (2018) assertion that future-oriented thinking motivates pedagogical innovation. Participants also reported that heavy workloads and rigid curricula hinder their ability to anticipate successful outcomes, echoing Reeve and Cheon (2021), who show that institutional barriers can diminish autonomy-oriented teaching. Instructors who balance realistic goals with flexible plans, however, feel more confident about fostering independent learning beyond class. This blend of future vision and adaptive practice supports Dörnyei and Kubanyiova’s (2014) argument that a prospective mindset benefits language learners.

In terms of resilience, our data show that instructors who manage their emotions can better navigate curricular shifts and heavy workloads, sustaining autonomy-supportive teaching. This echoes Gkonou and Miller’s (2023) view that emotion regulation is a relational process, carried out through, with, and for others. It also aligns with Chang et al.’s (2022) finding that instructors who practice emotion-regulation strategies and experience autonomy support report lower burnout and greater teaching enthusiasm. Regarding cognitive agility, Carroll et al. (2021) show that instructors who readily shift perspective and adapt strategy are viewed as more supportive, a pattern our data confirm. Similarly, cognitively agile instructors gravitate toward alternative, student-centered methods. We also find that optimism, self-compassion, and self-efficacy reinforce resilience; instructors who trust their institution’s backing for autonomy remain motivated despite setbacks, echoing Bouchard et al.’s (2017) argument that a positive outlook reframes obstacles as manageable. Self-compassion also plays a key role, as those who accept that fostering autonomy takes time experience less stress and greater perseverance (Neff, 2003). In contrast, instructors who blame themselves for setbacks report higher frustration and a reluctance to try new approaches. Similarly, self-efficacy, closely linked to resilience in prior work (Kılıç et al., 2020), supports autonomy-oriented teaching (Peng et al., 2022), with confident instructors adapting proactively, while those with shaken confidence tend to withdraw. These findings align with Wyatt (2018), who argues that strong self-efficacy beliefs encourage instructors to persist through challenges.

Participants’ elaborations on innovation highlight how divergent thinking, collaborative ideation, and iterative learning drive the adoption of new approaches that foster learner autonomy (Fontyn et al., 2025; Karaaslan & Çolak, 2024; Xie & Jiang, 2025). Instructors who generate creative solutions and adjust teaching strategies based on student feedback are better equipped to sustain out-of-class learning (Ventista & Brown, 2023; Xie & Jiang, 2025). However, insufficient feedback mechanisms and fear of institutional censure often hinder experimentation, as instructors in rigid institutional settings hesitate to explore alternative approaches (Fuad et al., 2020; Lin & Liu, 2025). Similarly, standardized curricula, limited resources, and inadequate training in creative pedagogy act as key barriers to innovation (Fuad et al., 2020; Marzuki et al., 2023). Addressing these challenges through flexible curricula, digital pedagogy training, and institutional encouragement for risk-taking allows instructors to develop more adaptive, student-centered practices. By modifying their methods through iterative learning and peer collaboration, instructors can confidently integrate new technologies and expand learner autonomy.

Social support emerges as a vital factor in autonomy-supportive teaching, encompassing emotional, instrumental, informational, and collegial dimensions (Dong et al., 2024; Reeve & Cheon, 2024). Instructors who feel supported by colleagues or administrators show greater commitment to fostering self-directed learning, with peer feedback and resource-sharing lightening the load of beyond-classroom tasks. This aligns with Mercer and Gregersen (2020), who highlight the role of professional communities in enhancing instructors’ well-being and persistence during pedagogical challenges. Belonging and inclusion also play a key role, as instructors within collaborative networks report higher motivation, while those lacking institutional backing feel isolated, often limiting their autonomy-supportive efforts. This mirrors Kaihoi et al. (2022), who find that collegial support acts as a protective factor against stress and burnout. Similarly, instructors in environments that encourage idea-sharing and co-planning report greater well-being and sustained motivation. Moreover, reciprocity and mutual growth drive instructional innovation, allowing instructors to navigate challenges and experiment with new methods in a supportive environment. Establishing strong social support systems that provide emotional encouragement, practical assistance, and knowledge sharing can alleviate workload pressures, thus strengthening autonomy-supportive teaching.

Our findings indicate that mattering functions as a proximal driver of autonomy-supportive engagement. The data clustered around the sense of significance, social recognition, and meaningful impact. When instructors observed student growth and received collegial feedback, they recommitted to beyond-classroom, autonomy-supportive strategies. This pattern aligns with evidence that diminished mattering is associated with poorer well-being and thoughts of exit, whereas feeling valued sustains investment in one’s role (Barrenechea, 2022). In parallel, reciprocal connection and personal alignment fostered ownership and motivation, consistent with findings that decision-making autonomy combined with administrative support predicts higher job satisfaction and lower burnout (Ha et al., 2025). Additionally, the data frequently linked feelings of replaceability, lack of recognition, and institutional constraints to reduced engagement and curtailed efforts beyond the classroom, mirroring research that heavy administrative burdens and rigid policies erode mattering and sap the bandwidth required for student-centred innovation (Agyapong et al., 2022; Marzuki et al., 2023). Practically, institutions can strengthen mattering and, in turn, WWB and learner autonomy by publicly acknowledging contributions, building structured peer-feedback channels, expanding growth opportunities, while allowing flexible guidelines for personalized instruction.

When considered together, this study highlights the pivotal role of WWB in enabling L2 instructors to cultivate learner autonomy and self-access learning. By demonstrating how the dimensions of the PRISM Model are interconnected with teaching practices, it becomes clear that supportive institutional cultures can significantly enhance an instructor’s effectiveness. When instructors envision positive outcomes, remain adaptable in the face of challenges, receive strong peer and administrative support, and experience a genuine sense of value in their roles, they are far more likely to create lasting opportunities for autonomous language development.

Institutional structures and policies either reinforce or hinder these efforts, shaping instructors’ professional agency in meaningful ways (Eteläpelto et al., 2013). The findings emphasize the need for targeted mentorship (Güven Yalçın, 2018; Üstündağ-Algın, 2023), hands-on teacher autonomy webinars (Üstündağ-Algın & Karaaslan, 2023), proactive policy guidelines, and systematic training that integrates the PRISM Model, helping instructors navigate the complexities of their work. At this stage, the participant profile (Table 1) enables a more nuanced discussion of age and experience. The data reveal marked intra-individual variation; the same instructor may report positive experiences in one PRISM dimension yet encounter difficulties in another. This pattern highlights the value of modular, needs-based PRISM professional-development programs that let instructors target specific dimensions rather than follow a uniform curriculum. Additionally, only two participants (T9 and T11) reported consistently positive experiences across all dimensions. As the oldest and most experienced instructors in the cohort, they exemplify the potential of relational mentoring (Üstündağ- Algın et al., 2023), whereby mentor instructors transmit autonomy-supportive practices, institutional knowledge, and learner-centred strategies to less-experienced colleagues.

Despite the illuminating insights, our study is not without limitations. As participants came from four distinct countries yet provided data that were not systematically compared across settings, the transferability of these findings to other contexts remains uncertain. Moreover, the small sample size of eleven participants constrains broad generalizations and indicates a need for further exploration.

Our study also represents an early step in the authors’ ongoing development of the PRISM Scale, which aims to provide a comprehensive framework for assessing WWB. As the scale is refined, future research could build on these qualitative insights by conducting longitudinal studies that track how instructors’ WWB evolves over time and subsequently influences the sustainability of self-access learning initiatives. It may also be fruitful to explore interventions that specifically strengthen one or more PRISM dimensions, such as targeted innovation training or mentorship programs, and examine how this impacts learner autonomy in the long term. Additionally, cross-institutional collaborations might clarify whether different mentorship styles or policy environments shape instructors’ sense of mattering and overall WWB in distinct ways.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our heartfelt gratitude to all participants who generously shared their time, experiences, and perspectives during the semi-structured interviews. Their openness and willingness to speak candidly were invaluable in shaping the insights presented in this study. Without their contributions, this research would not have been possible.

Notes on the Contributors

Pınar Üstündağ-Algın is a Ph.D. candidate in Applied Linguistics and an EFL/Turkish instructor at Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Türkiye. Her interests include workplace well-being, emotions, mentoring, method design, and ecological perspectives in language education. pinarustundagalgin@aybu.edu.tr

Hatice Karaaslan, PhD in Cognitive Science, Middle East Technical University, is an EFL instructor, a learning advisor, an advisor educator, and a student mentorship program coordinator in Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Türkiye, and a guest instructor at the Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education (RILAE, KUIS, Japan. hkaraaslan@aybu.edu.tr

Nurseven Kılıç, holding a Ph.D. in Psychological Counselling and Guidance from the Eskişehir Osmangazi University, Türkiye, works as an EFL instructor at Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University. nkilic@aybu.edu.tr

References

Agyapong, B., Obuobi-Donkor, G., Burback, L., & Wei, Y. (2022). Stress, burnout, anxiety, and depression among teachers: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), Article 10706. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710706

Barrenechea, I. (2022). Teachers’ perceived sense of well-being through the lens of mattering: Reclaiming the sense of community. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 7(4), 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-12-2021-0074

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Oettingen, G. (2016). Pragmatic prospection: How and why people think about the future. Review of General Psychology, 20(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000060

Benson, P. (2013). Teaching and researching autonomy (2nd ed.). Routledge.

BetterUp. (2025). About us. Retrieved February 12, 2025, from https://www.betterup.com/about-us

Borg, S., & Al-Busaidi, S. (2012). Teachers’ beliefs and practices regarding learner autonomy. ELT Journal, 66(3), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccr065

Bouchard, L. C., Carver, C. S., Mens, M. G., & Scheier, M. F. (2017). Optimism, health, and well-being. In D. S. Dunn (Ed.), Positive psychology: Established and emerging issues (pp. 112–130). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315106304-8

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, J. (2015). The future of work: Navigating the whitewater. Pacific Standard. https://psmag.com/economics/the-future-of-work-navigating-the-whitewater

Cangialosi, N., Odoardi, C., Peña-Jimenez, M., & Antino, M. (2023). Diversity of social ties and employee innovation: The importance of informal learning and reciprocity. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 39(2), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2023a8

Carroll, A., York, A., Fynes-Clinton, S., Sanders-O’Connor, E., Flynn, L., Bower, J. M., Forrest, K., & Ziaei, M. (2021). The downstream effects of teacher well-being programs: Improvements in teachers’ stress, cognition and well-being benefit their students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 689628. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.689628

Chang, M.-L., Gaines, R. E., & Mosley, K. C. (2022). Effects of autonomy support and emotion regulation on teacher burnout in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, Article 846290. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.846290

Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., Marsh, H. W., & Jang, H.-R. (2023). Cluster randomized control trial to reduce peer victimization: An autonomy-supportive teaching intervention changes the classroom ethos to support defending bystanders. American Psychologist, 78(7), 856–872. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001130

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Pearson.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

Derakhshan, A., Setiawan, S., & Ghafouri, M. (2024). Modeling the interplay of Indonesian and Iranian EFL teachers’ apprehension, resilience, organizational mattering, and psychological well-being. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 12(1), 21-43. https://doi.org/10.30466/ijltr.2024.121416

Ding, N., Wang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2024). English as a foreign language teacher’s well-being, resilience, and burnout. Porta Linguarum, 43, 147–166. https://doi.org/10.30827/portalin.vi43.28350

Dong, R. K., Li, X., & Hernan, B. R. (2024). Psychological safety and psychosocial safety climate in workplace: A bibliometric analysis and systematic review towards a research agenda. Journal of Safety Research, 91, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2024.08.001

Dörnyei, Z., & Kubanyiova, M. (2014). Motivating learners, motivating teachers: Building vision in the language classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., & Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educational Research Review, 10, 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.001

Fan, J., Lu, X., & Zhang, Q. (2024). The impact of teacher and peer support on preservice EFL teachers’ work engagement in their teaching practicum: The mediating role of teacher L2 grit and language teaching enjoyment. Behavioral Sciences, 14(9), 785. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090785

Flett, G. L. (2022). An introduction, review, and conceptual analysis of mattering as an essential construct and an essential way of life. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 40(1), 3–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/07342829211057640

Flett, G. L., Nepon, T., Goldberg, J. O., Rose, A. L., Atkey, S. K., & Zaki-Azat, J. (2022). The Anti-Mattering Scale: Development, psychometric properties, and associations with well-being and distress. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 40(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/07342829211050544

Fontyn, F., Tondeur, J., & Sermeus, J. (2025). A review of reviews on TPACK research: Is there any focus? Computers & Education Open, 9, 100285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2025.100285

Fuad, D. M., Musa, K., & Hashim, Z. (2020). Innovation culture in education: A systematic review of the literature. Management in Education, 36(3), 135–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020620959760

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

Good, D. J., & Yeganeh, B. (2012). Cognitive agility: Adapting to real-time decision making at work. OD Practitioner, 44(2), 13–17.

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82.

Güven Yalçın, G. (2018). Reflecting on successful elements of a mentoring session. Relay Journal, 1(2), 296–309. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010206

Ha, C., Pressley, T., & Marshall, D. T. (2025). Teacher voices matter: The role of teacher autonomy in enhancing job satisfaction and mitigating burnout. PLOS ONE, 20(1), e0317471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0317471

Karaaslan, H. (2019). Mentoring to promote professional well-being. Relay Journal, 2(2), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020206

Karaaslan, H., & Kılıç, N. (2019). Students’ attitudes towards blended language courses: A case study. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 15(1), 174–199. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/jlls/issue/44321/547699

Karaaslan, H., & Çolak, A. (2024, July 5). Tech-enhanced L2 learning: Autonomy and interdependence [Pre-recorded presentation]. 12th Lab Session on Curriculum for Learner Autonomy, Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education, Kanda University of International Studies, Chiba, Japan.

Kellerman, J., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2023). Tomorrowmind: Thriving at work with resilience, creativity, and connection—now and in an uncertain future. Atria Books.

Kılıç, N., Mammadov, M., Koçhan, K., & Aypay, A. (2020). The predictive power of general self-efficacy beliefs and body images of university students on resilience. Hacettepe University Journal of Education, 35(4), 904–914. https://doi.org/10.16986/HUJE.2018044245

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x

Kurtessis, J. N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M. T., Buffardi, L. C., Stewart, K. A., & Adis, C. S. (2017). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of Organizational Support Theory. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1854–1884. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315575554

Henry, A., & Thorsen, C. (2018). Teacher-student relationships and L2 motivation. The Modern Language Journal, 102(1), 218–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12446

Ingersoll, R. M. (2003). Who controls teachers’ work? Power and accountability in America’s schools. Harvard University Press.

Kaihoi, C. A., Bottiani, J. H., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2022). Teachers supporting teachers: A social network perspective on collegial stress support and emotional wellbeing among elementary and middle school educators. School Mental Health, 14(4), 1070–1085. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-022-09529-y

Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Lamb, T. (2008). Learner autonomy and teacher autonomy: Synthesizing an agenda. In T. Lamb & H. Reinders (Eds.), Learner and teacher autonomy: Concepts, realities, and responses (pp. 269–284). John Benjamins.

Lin, Y., & Liu, W. (2025). Beginning teachers’ innovative work behavior and stress towards change: Examining the roles of adaptability and contextual influences. Teaching and Teacher Education, 165, 105164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2025.105164

Little, D. (1991). Learner autonomy 1: Definitions, issues and problems. Authentik.

Marzuki, M., Indrawati, I., & Yunus, I. H. (2023). Teachers’ challenges in promoting learner autonomy: A socio-cultural perspective. Pioneer: Journal of Language and Literature, 15(1), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.36841/pioneer.v15i1.2853

McComb, S. E., Goldberg, J. O., Flett, G. L., & Rose, A. L. (2020). The double jeopardy of feeling lonely and unimportant: State and trait loneliness and feelings and fears of not mattering. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 563420. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.563420

Mercer, S., & Gregersen, T. (2020). Teacher wellbeing. Oxford University Press.

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

O’Reilly, J., Ranft, F., & Neufeind, M. (2018). Work in the digital age: Challenges of the fourth industrial revolution.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

Pearson, L. C., & Moomaw, W. (2005). The relationship between teacher autonomy and stress, work satisfaction, empowerment, and professionalism. Educational Research Quarterly, 29(1), 38–54.

Peng, Y., Wu, H., & Guo, C. (2022). The relationship between teacher autonomy and mental health in primary and secondary school teachers: The chain-mediating role of teaching efficacy and job satisfaction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215021

Reece, A., Carr, E., Baumeister, R., & Kellerman, G. R. (2021). Outcasts and saboteurs: Intervention strategies to reduce the negative effects of social exclusion on team outcomes. PLOS ONE, 16(5), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249851

Reece, A., Yaden, D., Kellerman, G., Robichaux, A., Goldstein, R., Schwartz, B., Seligman, M., & Baumeister, R. (2021). Mattering is an indicator of organizational health and employee success. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(2), 228–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1689416

Reeve, J., & Cheon, S. H. (2021). Autonomy-supportive teaching: Its malleability, benefits, and potential to improve educational practice. Educational Psychologist, 56(1), 54–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2020.1862657

Reeve, J., & Cheon, S. H. (2024). Learning how to become an autonomy-supportive teacher begins with perspective taking: A randomized control trial and model test. Teaching and Teacher Education, 148, 104702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2024.104702

Reinders, H., & White, C. (2016). 20 years of autonomy and technology: How far have we come and where to next? Language Learning & Technology, 20(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.64152/10125/44466

Richards, J. C. (2015). Key issues in language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Sage.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2014). Teacher self-efficacy and perceived autonomy: Relations with teacher engagement, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion. Psychological Reports, 114(1), 68–77. https://doi.org/10.2466/14.02.PR0.114k14w0

Taleb, N. N. (2012). Antifragile: Things that gain from disorder. Random House.

Üstündağ-Algın, P. (2023). “If I don’t get lost, I will never find a new route”: Engaging with my mentee in my first mentoring session. Relay Journal, 5(2) 107–116. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/050205

Üstündağ-Algın P., Karaaslan H. (2023). Review: Teacher autonomy webinar. IATEFL LASIG The Newsletter of the Learner Autonomy Special Interest Group, Issue 83, 28–32.

Üstündağ-Algin, P.,Karaaslan, H., & Murphey, T. (2023). Leader-ship as an empathy-based sharing-caring-ship of partnered ethical-ecological teaching and mentor shipping. Relay Journal, 5(2), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/050203

Ventista, O. M., & Brown, C. (2023). Teachers’ professional learning and its impact on students’ learning outcomes: Findings from a systematic review. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 8(1), 100565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100565

Wang, Y. (2024). Exploring the impact of workload, organizational support, and work engagement on teachers’ psychological wellbeing: A structural equation modeling approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1345740. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1345740

Wu, S., Xu, Q., Tian, H., Li, R., & Wu, X. (2025). The relationship between social support and work engagement of rural teachers: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1479097. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1479097

Wyatt, M. (2018). Language teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs: A review of the literature (2005-2016). Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4). https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v43n4.6

Xie, L., & Jiang, L. (2025). Promoting second language writing autonomy through digital multimodal composing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 69, 101225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2025.101225

Yılmaz Dinç, S., & Kılıç, N. (2025). Effectiveness of EMDR-focused group counseling in reducing exam anxiety among middle school students. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.34133/jemdr.0011

Zhang, L. (2023). Reviewing the effect of teachers’ resilience and wellbeing on their foreign language teaching enjoyment. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, Article 1187468. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1187468