Muhammed Özgür Yaşar, Eskişehir Osmangazi University, Turkey. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7167-2192

Yaşar, M. O. (2025). Developing self-regulated learning in ELT through a video-based pedagogical framework (VIDPEF): A conceptual model for EFL learners. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(1), 76–99. https://doi.org/10.37237/160105

Abstract

This article introduces a video-based pedagogical framework (VIDPEF) designed to foster self-regulated learning (SRL) among English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students. Centered on self-made videos and implemented within a MOOC-supported flipped classroom, this model enhances learner autonomy, reflective practice, and active engagement in the learning process. Each phase of the model is rooted in SRL theory and includes practical guidelines for educators to implement effectively. This framework offers English Language Teaching (ELT) practitioners a flexible, student-centered approach to develop SRL in language learning contexts, supporting EFL learners’ progress as autonomous and reflective learners.

Keywords: Self-regulated learning, ELT, video-based learning, VIDPEF, EFL learners

The importance of self-regulated learning (SRL) in language education, particularly in English Language Teaching (ELT), has grown with the demand for lifelong learning skills and learner autonomy (Hunutlu, 2023; Sutiyono et al., 2023; Yastibas & Yastibas, 2015; Zhang & Zhang, 2019). As English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners become more active participants in their learning process, they benefit from a shift towards reflective, SRL environments (An et al., 2021; Delgado Alvarado, 2024; Erdoğan, 2018). However, traditional ELT methods often do not fully engage students in SRL practices, which are essential for developing effective language skills and motivation (Çelik et al., 2012; Gardner et al., 2023; Hemmati et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2024; Morshedian et al., 2017).

The constructivist approach, which underpins the pedagogical framework in this study, views learning as an active, reflective process where knowledge is constructed through experience (De Corte, 2012; Robertson et al., 2024). This approach aligns well with the use of video creation, as it provides students with a hands-on way to construct knowledge, actively engage with content, and reflect on their understanding. In this framework, creating videos encourages students to be more autonomous, motivated, and initiative-taking learners, transforming the classroom into a space for collaborative feedback and refinement.

The framework introduced in this article aims to address this gap by providing ELT educators with a structured model for promoting SRL. Using self-made video assignments, students engage in reflective practices and receive peer feedback, all within a flipped classroom model supported by a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC). The video creation process, combined with reflective practices, allows learners to develop metacognitive skills, fosters self-assessment, and improves their language abilities in a collaborative, active learning style.

This framework is crucial as it empowers learners to take control of their learning process, fostering autonomy through self-directed video creation and reflection. By engaging in self-access learning, students independently plan, produce, and evaluate their videos, reinforcing their ability to regulate their own learning without constant teacher intervention. This approach aligns with constructivist principles, where learners actively construct knowledge through experience. Moreover, the integration of peer feedback promotes social learning, helping students refine their strategies. Ultimately, this model supports lifelong learning skills, equipping EFL learners with the confidence and self-regulation needed for continuous language development.

The development of this pedagogical framework is grounded in both theory and practice. It was initially tested in a doctoral research study that examined its effects on SRL and foreign/second language (L2) speaking skills among pre-service ELT teachers (Yaşar, 2024). The study’s findings indicated significant improvements in students’ SRL levels, as well as enhanced confidence and L2 speaking performance. These outcomes suggest that integrating self-made videos with reflective stages can effectively support autonomy and motivation in language learning. Although studies have demonstrated that self-made videos can provide many advantages, research specific to ELT contexts remains limited. This study thus aims to bridge this gap by developing a pedagogical framework, investigating how self-made videos can foster SRL and communication skills among pre-service ELT students.

Theoretical Foundation

Self-Regulated Learning

SRL emphasizes learners’ ability to plan, monitor, and evaluate their learning independently (Zimmerman, 1989). Recent scholarly work has extensively explored SRL, drawing on theories such as metacognition, social cognitive theory, and self-efficacy. While these theories provide valuable insights into the mechanisms of SRL, contemporary research has primarily focused on the cognitive and social factors influencing learners’ self-regulation (Moos & Bonde, 2016; Zhu et al., 2020). For example, scholars like Pintrich (2000) and Zimmerman (1989) have emphasized the role of metacognitive strategies, such as self-monitoring and self-evaluation, in facilitating effective learning.

Similarly, Bandura’s (1991) social cognitive theory emphasizes the importance of observational learning in SRL, suggesting that individuals learn by observing and imitating the behaviors of others. In the context of SRL, individuals develop self-efficacy, self-judgment, and self-regulation skills by observing and modelling the behaviors of competent individuals. This enables them to set goals, monitor their progress, and adjust their strategies to achieve their desired outcomes. Flavell’s (1979) work on metacognition has highlighted the importance of cognitive control processes, such as planning, monitoring, and evaluating, in regulating learning. These processes allow learners to actively engage with the learning material and make informed decisions about their learning strategies.

Moreover, recent studies have extended SRL research into video-based learning environments. Delen et al. (2014) demonstrated that video-based learning enhances learners’ language skills especially L2 speaking and learner autonomy. Similarly, Wass and Rogers (2019) found that video reflection approach and peer mentoring enhance tutors’ teaching, improve confidence and presentation capabilities while reducing communication anxiety. Rosenthal et al. (2024) also highlighted the role of video-based interactive learning in improving learning outcomes and fostering SRL, while Campbell et al. (2020) emphasized the improved perceptions of self-efficacy, evidence of student engagement, increase in students’ perceived content knowledge, along with autonomy and motivation gains from student-created videos. These findings reinforce the potential of video-based learning to cultivate SRL skills in language education.

Building upon these foundational concepts, the pedagogical framework introduced in this article aligns with SRL principles by encouraging students to set goals, reflect on their performance, and actively seek feedback. The model involves metacognitive, motivational, and behavioural processes that allow learners to control their learning environment and actions, as will be described in the next section.

Video-Based Learning in ELT

Video-based learning, particularly in language education, offers numerous benefits for EFL learners (Cavanagh et al., 2014; Yamashita & Nakajima, 2010). It enables learners to practice their speaking and presentation skills, build confidence, and reflect on their progress through visual recordings (Miyata, 2002; Star & Strickland, 2008). Research indicates that self-made videos can enhance motivation and engagement, making this approach particularly effective for language learning (Shyr & Chen, 2016; Wang & Hartley, 2003).

Similarly, video-based learning benefits from a constructivist view of language pedagogy, as this view emphasizes learner autonomy and self-directed learning (Stoller, 2006). While traditional methods often rely on teacher-centered instruction, video-making aligns with this constructivist approach, fostering experiential, individual, and autonomous learning (Brydon-Miller & Maguire, 2009). Consequently, this pedagogical framework is consistent with the broader shift in language learning towards more learner-centered and constructivist methodologies, where video-making has emerged as a valuable tool for language learners (Lantolf & Thorne, 2006; Rüschoff & Ritter, 2001).

Research by Wang and Tang (2024) demonstrated that video-based assignments improve metacognitive awareness and self-regulation in video-based learning. Similarly, Wang and Hartley (2003) found that student-generated videos enhance self-efficacy and motivation in language learning. Moos and Bonde (2016) explored how video-based learning supports SRL strategies, including goal-setting and self-monitoring. Additionally, Sun and Rueda (2012) emphasized that video reflections foster self-regulatory behaviors and learner autonomy. These studies provide strong empirical backing for integrating video-based learning into SRL-focused pedagogies.

The study testing the proposed video-based pedagogical model was conducted in a state university in Turkey with pre-service English language teachers enrolled in a Listening and Pronunciation I course (Yaşar, 2024). Utilizing an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design, the research employed a pretest-posttest quasi-experimental approach, comparing an experimental group using self-made videos with a control group following a traditional MOOC-based flipped classroom model. Findings indicated that self-made videos significantly enhanced SRL, L2 speaking performance, and course achievement. Participants reported increased autonomy, motivation, and engagement, highlighting the potential of video-based learning in ELT.

The video-based learning framework in this study comprises two distinct phases. In the initial phase, learners create their own videos to demonstrate their understanding of the course material. Subsequently, they share their videos with classmates, providing feedback and learning from each other. This process facilitates a collaborative peer review process, enabling learners to critically analyse their own work and provide constructive feedback to their peers. This reciprocal exchange of feedback fosters a deeper understanding of the subject matter and enhances the overall learning experience.

The pedagogical model for self-made videos is based on the three domains of communication outlined by Morreale et al. (1993): cognitive, behavioural, and affective. The cognitive domain focuses on knowledge and understanding of the communication process. By creating and analysing videos, learners can develop critical thinking, problem-solving, and metacognitive skills. The behavioural domain emphasizes the practical skills of communication, such as speaking, listening, and nonverbal communication. Video creation provides opportunities to practice and refine these skills. The affective domain relates to learners’ emotions, attitudes, and motivation. By reflecting on their own work and providing feedback to peers, learners can develop a positive attitude towards language learning and increase their confidence.

Overview of the Video Based Pedagogical Framework (VIDPEF)

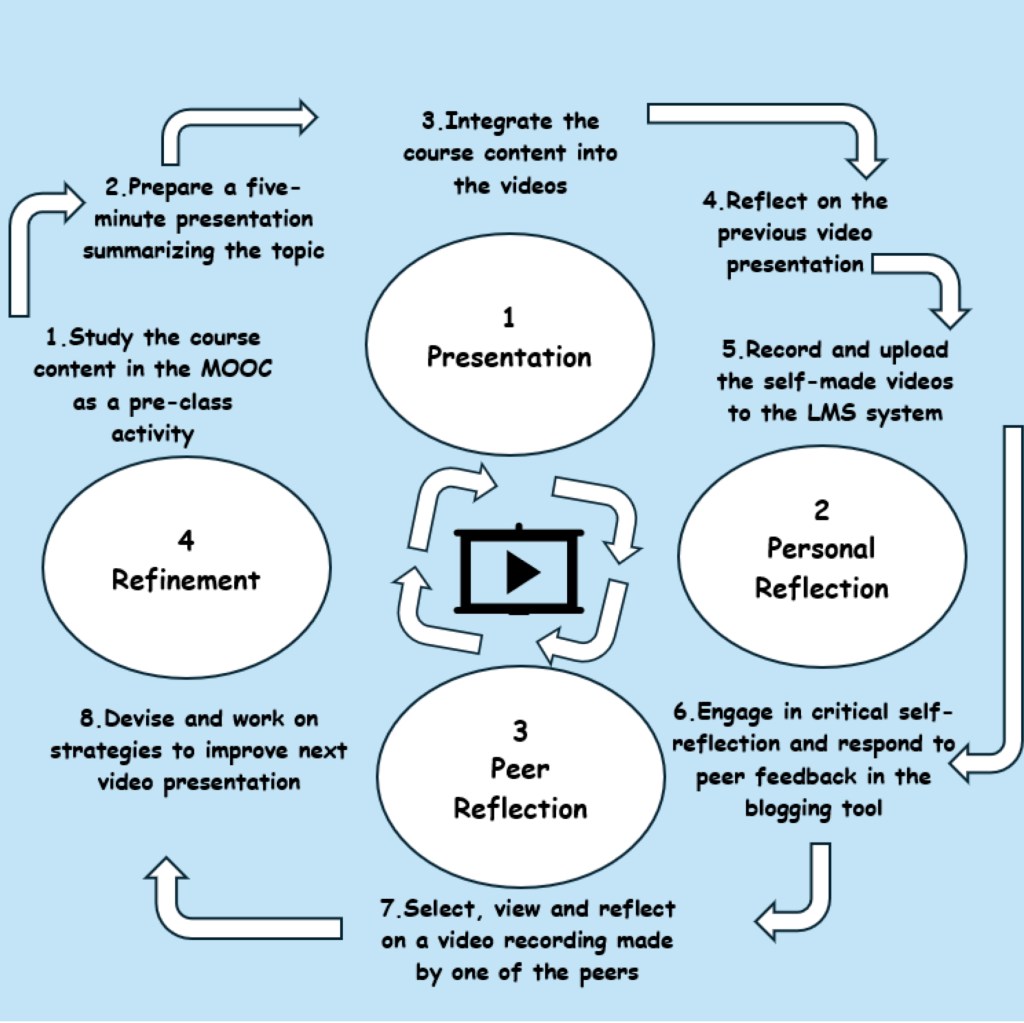

This video-based pedagogical framework (VIDPEF) is designed to encourage SRL through a structured, reflective, and collaborative approach to video creation. It consists of four stages: Presentation, Personal Reflection, Peer Reflection, and Refinement. Each stage incorporates SRL principles and is crafted to develop autonomy, critical thinking, and language proficiency. Figure 1 shows the pedagogical cycle used for the VIDPEF, enabling students to engage deeply with the course material, practice L2 speaking skills, and enhance metacognitive skills through iterative reflection and peer feedback.

This model has been applied in a freshman-year ELT course focused on listening and pronunciation at a state university in Turkey. The participants were pre-service English language teachers with an intermediate to upper-intermediate proficiency level. VIDPEF aligns with curriculum goals by promoting communicative competence, metacognitive awareness, and autonomous learning. It enhances speaking, listening, and reflective thinking skills while fostering learner autonomy through video-based tasks. By integrating SRL principles, the framework supports students in achieving both linguistic and strategic competence essential for their professional and academic development.

SRL principles encompass cognitive, motivational, and behavioural aspects that promote learner autonomy and effective learning management (Pintrich, 2000; Zimmerman, 1989). Based on this theoretical foundation, a detailed breakdown of SRL principles relevant to each stage in the VIDPEF is provided below.

Figure 1

Stages of the VIDPEF for Self-regulated Learning

SRL Principles Incorporated Into Each Stage

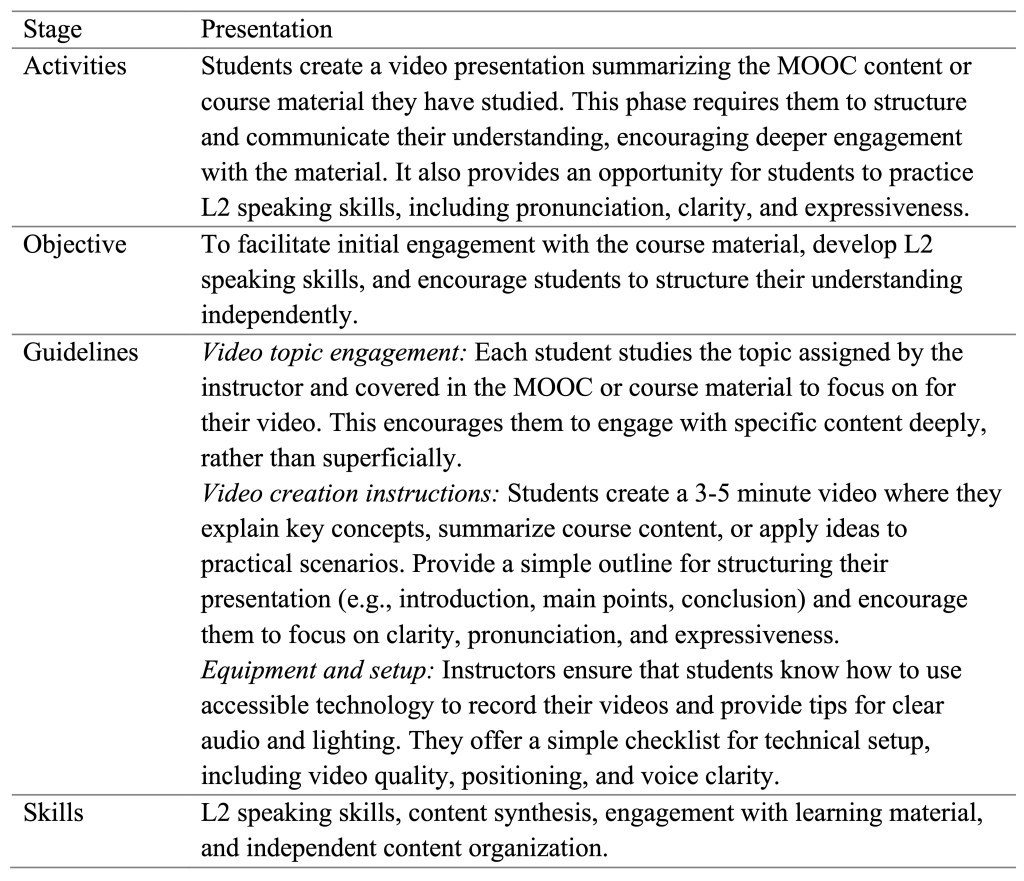

Presentation and SRL Principles: Goal Setting and Task Strategies

In the presentation stage, students actively engage in goal setting by determining what they aim to achieve through their video presentation (e.g., clarity, depth of understanding, or improved pronunciation). According to Zimmerman’s model (1989), setting specific learning goals helps students direct their focus and motivation toward meaningful outcomes. Students also apply task strategies to organize their presentation content, ensuring they address key points effectively. These strategies are fundamental for planning, organizing, and implementing a structured approach to the presentation, which are critical cognitive components in SRL. Table 1 below presents a step-by-step guide to the presentation stage of the VIDPEF.

Table 1

A Step-by-Step Guide to the Presentation Stage of the VIDPEF

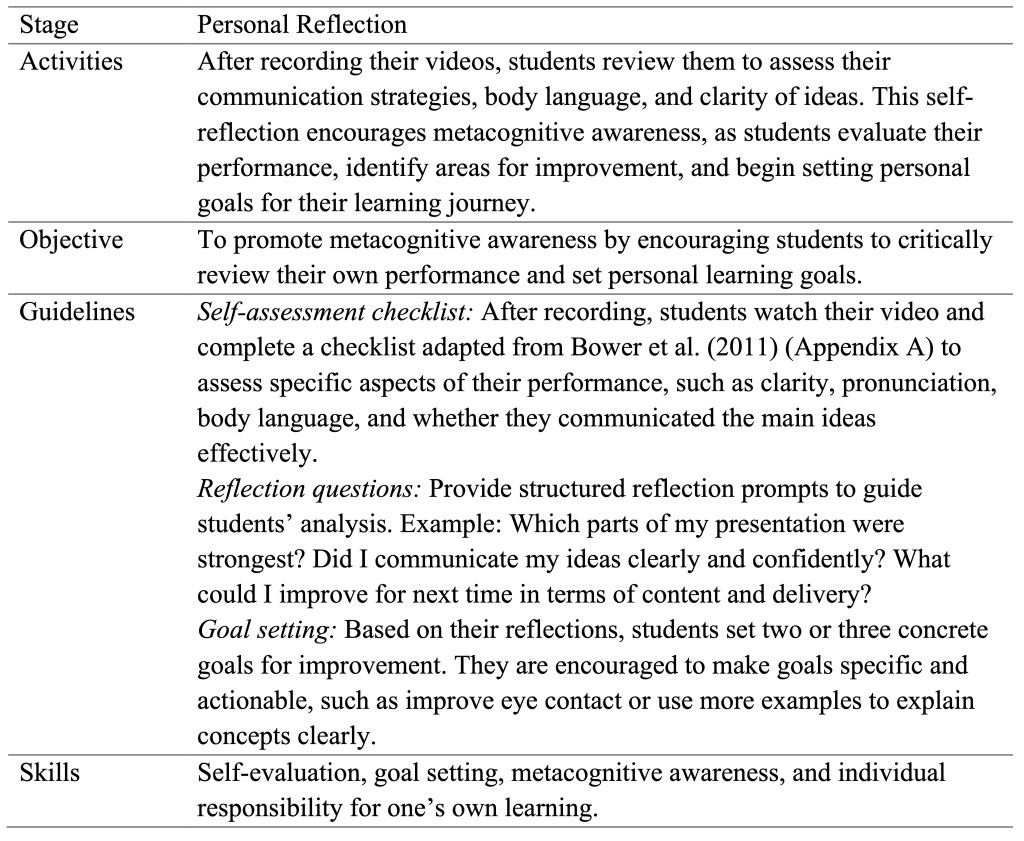

Personal Reflection and SRL Principles: Self-Monitoring and Self-Evaluation

During the personal reflection stage, students engage in self-monitoring as they review their recorded videos to identify strengths and areas for improvement. Self-monitoring involves tracking one’s progress toward goals and is crucial for maintaining focus on task performance. Following self-monitoring, students engage in self-evaluation, assessing their performance against their personal standards or rubric criteria. This aligns with Pintrich’s SRL model (2000), where self-evaluation helps learners measure their success, adjust their strategies, and reinforce intrinsic motivation. Table 2 below shows a step-by-step guide to the personal reflection stage of the VIDPEF.

Table 2

A Step-by-Step Guide to the Personal Reflection Stage of the VIDPEF

Peer Reflection and SRL Principles: Seeking Feedback and Social Learning

The peer reflection stage incorporates feedback-seeking behaviors, a key SRL strategy that encourages learners to obtain constructive input from others. Seeking feedback aligns with the SRL principle of adapting one’s learning strategies based on new information. In this collaborative process, students engage in social learning, where they learn through observation and interaction with their peers, a concept also highlighted in Bandura’s (1991) social cognitive theory. Peer feedback promotes cognitive and affective engagement, helping students to view their work from new perspectives and refine their self-assessment practices. Table 3 below indicates a step-by-step guide to the peer reflection stage of the VIDPEF.

Table 3

A Step-by-Step Guide to the Peer Reflection Stage of the VIDPEF

Refinement and SRL Principles: Strategy Adjustment and Reflective Practice

In the refinement stage, students implement strategy adjustment by modifying their presentation based on personal reflection and peer feedback. This process aligns with Zimmerman’s (1989) idea of self-regulation as an iterative process, where learners continually adjust their strategies to achieve their goals. Reflective practice is also central to this stage, as students consider their learning journey and set goals for future improvement. This practice enhances metacognitive awareness and encourages a growth-oriented mindset, reinforcing the cycle of goal setting, monitoring, and self-evaluation. Table 4 below describes a step-by-step guide to the refinement stage of the VIDPEF.

Table 4

A Step-by-Step Guide to the Refinement Stage of the VIDPEF

Practical Guidelines for the Implementation of the VIDPEF

The implementation of VIDPEF follows a structured timeline to ensure students engage meaningfully with each phase. The full cycle of video creation, reflection, and revision is designed to be completed within two weeks, allowing sufficient time for students to process feedback and refine their work. To support self-regulated learning, reflection questions are integrated into the process. Students are encouraged to assess their progress by considering prompts such as: “What did I learn through creating this video?”, “Which areas of my presentation do I feel most confident about?”, and “What specific improvements can I make for future presentations?” These guided reflections help learners develop metacognitive awareness and refine their language skills.

Peer feedback plays a crucial role in this framework. To ensure constructive and focused evaluations, students use rubrics that assess clarity, engagement, body language, and content organization. This structured approach helps learners provide meaningful feedback while developing their critical analysis skills. Moreover, creating a supportive environment is essential for the success of peer review. Instructors are encouraged to foster a classroom culture where feedback is viewed as a learning tool rather than criticism. Emphasizing a growth mindset helps students embrace feedback positively, ultimately enhancing their autonomy and confidence in language learning.

Assessment Methodology

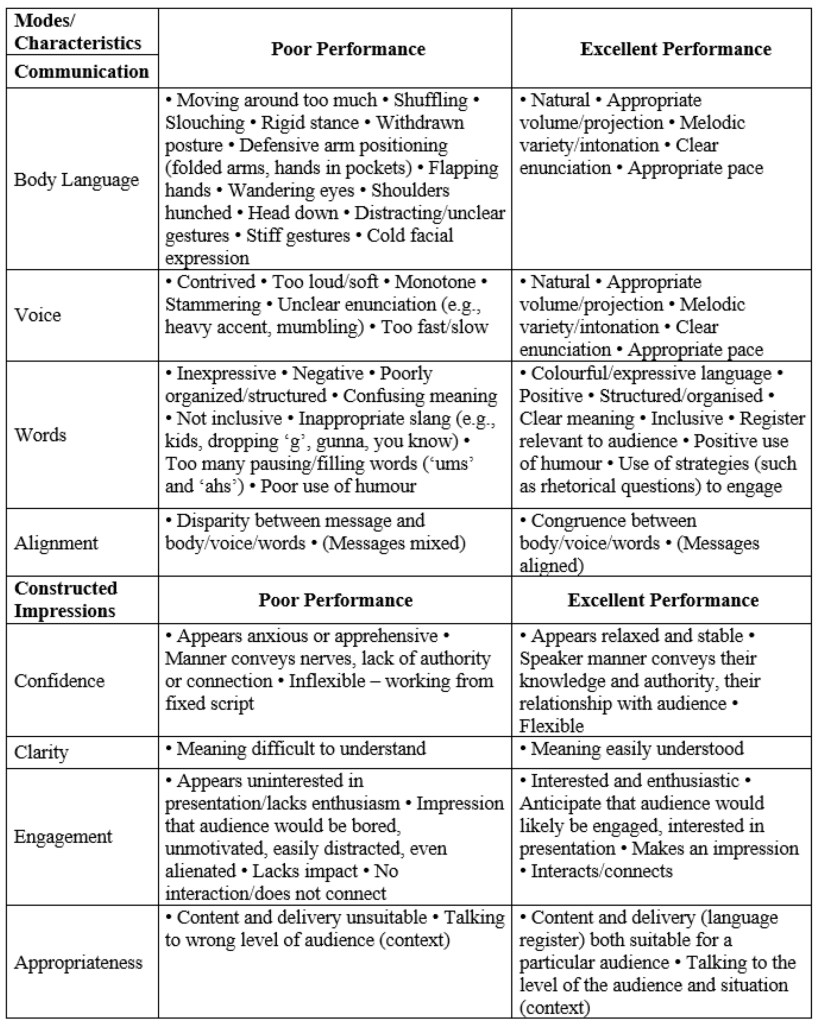

The assessment approach has been designed to provide structured feedback and track SRL progression. Each presentation is rated by the instructor based on the following criteria designed by Cavanagh et al. (2014, p. 6):

- The quality of overall presentation performance

- The quality of body-language

- The quality of voice

- The quality of words used

- The alignment between body-language, voice and words

- The confidence of the presenter

- The clarity of the presenter

- The extent to which the presenter was engaging

- The appropriateness of the presenter’s presentation.

To establish a consistent scoring system for the nine criteria, a scale of 0 to 10 was used. Each score corresponds to specific performance characteristics, ranging from poor to excellent, as outlined by Cavanagh et al. (2014) (see Appendix D). To ensure transparency and facilitate SRL, students are provided with the assessment criteria before the video creation process begins. The rubric serves as a guideline, helping students set goals, self-monitor their progress, and refine their presentations accordingly. The instructor incorporates these criteria into formative assessment by offering structured feedback at each stage of the VIDPEF model. Peer evaluations also utilize the same rubric, allowing students to critically assess their own and their peers’ work, fostering a deeper understanding of effective communication and self-regulation.

Anticipated Outcomes and Educational Implications

This pedagogical framework is expected to yield several benefits. Through self-assessment and goal setting, students enhance their ability to regulate their learning process, fostering improved SRL skills. The iterative video process builds confidence, fluency, and communication skills, particularly in L2 speaking, contributing to enhanced language proficiency. Additionally, the model encourages independent learning and personal responsibility, which are essential for language acquisition and lifelong learning. By integrating these elements, the framework supports students in developing autonomy, metacognitive awareness, and effective learning strategies in ELT contexts.

In addition to the anticipated theoretical benefits, this pedagogical framework has been empirically validated in Yaşar’s (2024) doctoral research study conducted with pre-service ELT teachers, revealing notable gains in SRL and L2 speaking skills among participants. Specifically, students demonstrated increased autonomy, goal-setting abilities, and a more active approach to managing their learning. The regular use of video-based assignments and structured reflection enabled learners to critically assess their progress and improve their L2 communication skills. Qualitative data further revealed that participants reported increased confidence, self-monitoring, and motivation, indicating that the model effectively fosters independent learning and self-regulation. These empirical findings and qualitative data reinforce the framework’s potential to support SRL in diverse ELT contexts, making it a valuable tool for educators aiming to foster learner independence and reflective practice.

In this regard, this framework can be adapted to suit different ELT contexts, including hybrid, online, or in-person formats, providing educators with a versatile tool for fostering SRL. For online learning, educators can implement asynchronous video submissions combined with structured self-assessment checklists to encourage independent reflection. In hybrid settings, video-based tasks can be integrated into collaborative online platforms where students provide peer feedback before in-class discussions. By blending digital and reflective practices, the VIDPEF aligns well with current trends in flipped and blended learning, making it suitable for integration in modern language curricula.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The VIDPEF offers a structured approach for fostering SRL in ELT. By combining self-made videos with reflective practices, the model enables learners to take charge of their language development actively. This conceptual model provides a foundation for educators seeking to implement SRL in language courses, offering a pathway to increased learner autonomy and engagement. While the VIDPEF provides a structured approach to fostering SRL, its implementation may present challenges. For instance, students unfamiliar with SRL may require additional scaffolding to effectively engage with the reflective and peer-feedback processes. Moreover, the model’s reliance on video-based tasks necessitates access to appropriate technological resources, which may not always be feasible in all educational settings. Future studies should consider these limitations and explore strategies to enhance accessibility and support for diverse learner needs.

Future research could investigate the long-term effects of this framework on SRL development and language performance. Additionally, exploring its application across different language skills, such as listening or writing, could provide further insights into its broader impact on language learning. Future research could also delve deeper into the potential of this framework by exploring its impact on learners of various age groups, including children, adults, and lifelong learners, different language proficiencies, and in diverse contexts. Finally, applying this model to other courses within ELT programs and other teacher education programs could broaden its potential applications.

Notes on the Contributor

Muhammed Özgür Yaşar is a lecturer in the Faculty of Education at the English Language Teaching Department, Osmangazi University in Eskişehir Türkiye. He holds a PhD in ELT. His research interests include self-regulated learning, multilingualism, language identity development, and English Language Teaching in the MOOCs environment and flipped EFL classrooms.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to extend sincere thanks to the Eskişehir Osmangazi University Faculty of Education, Foreign Language Education Department, for their support throughout this research. Special appreciation is also due to the pre-service English language teachers, whose participation made this study possible.

References

An, Z., Wang, C., Li, S., Gan, Z., & Li, H. (2021). Technology-assisted self-regulated English language learning: Associations with English language self-efficacy, English enjoyment, and learning outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 558466. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.558466

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-L

Bower, M., Cavanagh, M., Moloney, R., & Dao, M. (2011). Developing communication competence using an online video reflection system: Pre-service teachers’ experiences. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39(4), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2011.614685

Brydon-Miller, M., & Maguire, P. (2009). Participatory action research: Contributions to the development of practitioner inquiry in education. Educational Action Research, 17(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790802667469

Campbell, L. O., Heller, S., & Pulse, L. (2020). Student-created video: an active learning approach in online environments. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(6), 1145–1154. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1711777

Cavanagh, M., Bower, M., Moloney, R., & Sweller, N. (2014). The effect over time of a video-based reflection system on preservice teachers’ oral presentations. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(6), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2014v39n6.3

Çelik, S., Arkin, E., & Sabriler, D. (2012). EFL learners’ use of ICT for self-regulated learning. The Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 8(2), 98–118. http://www.jlls.org/vol8no2/98-118.pdf

De Corte, E. (2012). Constructive, self-regulated, situated, and collaborative learning: An approach for the acquisition of adaptive competence. Journal of Education, 192(2–3), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022057412192002-307

Delen, E., Liew, J., & Willson, V. (2014). Effects of interactivity and instructional scaffolding on learning: Self-regulation in online video-based environments. Computers & Education, 78, 312–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.06.018

Delgado Alvarado, N. (2024). Fostering language learning through a training model embedding self-regulated learning (SRL) and integrative learning technologies (ILT): Action-research at a Mexican University (Doctoral dissertation, University of Southampton).

Erdoğan, T. (2018). The investigation of self-regulation and language learning strategies. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(7), 1477–1485. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2018.060708

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

Gardner, D., Lau, K., Tseng, M. L., Yu, L-T., & Yuan, Y-P. (2023). Language learning beyond the classroom in an Asian context: Obstacles encountered. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(2), 106–135. https://doi.org/10.37237/140202

Hemmati, F., Sotoudehnama, E., & Morshedian, M. (2018). The impact of teaching self-regulation in reading on EFL learners’ motivation to read: Insights from an SRL model. Journal of Modern Research in English Language Studies, 5(4), 131–155. https://doi.org/10.30479/jmrels.2019.10583.1325

Hunutlu, Ş. (2023). Self-regulation strategies in online EFL/ESL learning: A systematic review. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(2), 136–166. https://doi.org/10.37237/140203

Lantolf, J., & Thorne, S. (2006). Sociocultural theory and the genesis of second language development. Oxford University Press.

Liu, Z. M., Hwang, G. J., Chen, C. Q., Chen, X. D., & Ye, X. D. (2024). Integrating large language models into EFL writing instruction: Effects on performance, self-regulated learning strategies, and motivation. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2024.2389923

Miyata, H. (2002, December). A study of developing reflective practices for preservice teachers through a web-based electronic teaching portfolio and video-on-demand assessment program. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computers in Education (pp. 1039–1043). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/CIE.2002.1186145

Morreale, S., Hackman, M., Ellis, K., King, K., Meade, P. A., & Pinello-Tegtmeier, L. (1993, November). Assessing communication competency in the interpersonal communication course: A laboratory-supported approach. Paper presented at the seventy-ninth annual meeting of the Speech Communication Association, Miami Beach, FL.

Moos, D. C., & Bonde, C. (2016). Flipping the classroom: Embedding self-regulated learning prompts in videos. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 21(2), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-015-9269-1

Morshedian, M., Hemmati, F., & Sotoudehnama, E. (2017). Training EFL learners in self-regulation of reading: Implementing an SRL model. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 33(3), 290–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2016.1213147

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of Self-Regulation (pp. 451–502). Academic Press.

Robertson, J., Ferreira, C., Botha, E., & Oosthuizen, K. (2024). Game changers: A generative AI prompt protocol to enhance human-AI knowledge co-construction. Business Horizons, 67(5), 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2024.03.001

Rosenthal, A., Hirt, C. N., Eberli, T. D., Jud, J., & Karlen, Y. (2024). Video-based classroom insights: Promoting self-regulated learning in the context of teachers’ professional competences and students’ skills in self-regulated learning. Unterrichtswissenschaft, 52(1), 39–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42010-023-00189-8

Rüschoff, B., & Ritter, M. (2001). Technology-enhanced language learning: Construction of knowledge and template-based learning in the foreign language classroom. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 14(3–4), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1076/call.14.3.219.5789

Shyr, W., & Chen, C. (2016). Designing a technology-enhanced flipped learning system to facilitate students’ self-regulation and performance. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34(1), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12213

Star, J. R., & Strickland, S. K. (2008). Learning to observe: Using video to improve preservice mathematics teachers’ ability to notice. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 11(2), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-007-9063-7

Stoller, F. (2006). Establishing a theoretical foundation for project-based learning in second and foreign language contexts. In G. H. Beckett & P. C. Miller (Eds.), Project-based second and foreign language education: Past, present, and future (pp. 19–40). Information Age Publishing.

Sun, J. C. Y., & Rueda, R. (2012). Situational interest, computer self‐efficacy and self‐regulation: Their impact on student engagement in distance education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(2), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01157.x

Sutiyono, C., Arapah, E., & Triana, N. (2023). Self-regulated learning (SRL) in English language teaching. Proceedings of EEIC, 3, 294–305. https://jurnal.usk.ac.id/eeic/article/view/37059

Wang, J., & Hartley, K. (2003). Video technology as a support for teacher education reform. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 11(1), 105–138. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/17791/

Wang, J., & Tang, H. (2024). Effects of self-regulated learning prompts at three different phases in video-based learning. Journal of Formative Design in Learning 8, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41686-024-00093-z

Wass, R., & Rogers, T. (2019). Using video-reflection and peer mentoring to enhance tutors’ teaching. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 58(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2019.1695646

Yamashita, Y., & Nakajima, T. (2010, June). Using a new information system for analysis of the relation between presentation skills and understandability. In EdMedia+ Innovate Learning (pp. 3162–3167). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Yastibas, A. E., & Yastibas, G. C. (2015). The use of e-portfolio-based assessment to develop students’ self-regulated learning in English language teaching. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 176, 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.437

Yaşar, M. Ö. (2024). The effects of self-made videos on students’ self-regulated learning, L2 speaking performance, and course achievement in a MOOC-based flipped classroom model [Doctoral dissertation, Bahçeşehir University]. Council of Higher Education Theses Database. 877305 http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.28879.80806

Zhang, D., & Zhang, L. J. (2019). Metacognition and self-regulated learning (SRL) in second/foreign language teaching. In Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 883–897). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02899-2_47

Zhu, Y., Mustapha, S. M., & Gong, B. (2020). Review of self-regulated learning in Massive Open Online Courses. Journal of Education and Practice, 11(8), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.7176/jep/11-8-02

Zimmerman, B. J. (1989). A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(3), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.81.3.329

Appendix A

Self-Assessment Checklist for Video Presentation

For each statement, rate yourself on a scale of 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree):

1. Content and Structure

I clearly communicated the main ideas of the topic.

My presentation was logically structured with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion.

I used examples or explanations to support my points.

I stayed focused on the topic without unnecessary digressions.

2. Clarity and Pronunciation

My voice was clear and easy to understand.

I spoke at a steady pace that was neither too fast nor too slow.

I pronounced words accurately and correctly.

I used pauses effectively to emphasize key points.

3. Engagement and Expressiveness

I maintained eye contact with the camera to engage viewers.

My facial expressions matched the tone of my presentation.

I used appropriate gestures to reinforce my message.

My tone was varied and expressive, not monotone.

4. Body Language

I displayed confident and open body language.

I avoided distracting movements (e.g., fidgeting, looking away frequently).

My posture was appropriate and professional.

I stayed within the frame and maintained an appropriate distance from the camera.

5. Overall Reflection

I am satisfied with my overall presentation.

I feel my presentation conveyed the topic effectively.

I identified specific areas for improvement.

I set goals to improve my performance in future presentations.

Reflective Questions

What went well in this presentation?

Which aspects could I improve?

What specific goals will I set for my next presentation?

Appendix B

Peer Feedback Form for Video Presentation

Peer’s Name:

Reviewer’s Name:

Date:

For each category, rate your peer’s presentation on a scale of 1-5:

1 = Needs Improvement

2 = Fair

3 = Satisfactory

4 = Good

5 = Excellent

1. Content and Understanding

The main ideas were clearly communicated.

The presentation was well-organized and easy to follow.

The speaker used examples or explanations to support their points.

Comments:

What worked well?

Are there any areas where the content could be clearer?

2. Clarity and Pronunciation

The speaker’s voice was clear and easy to understand.

Pronunciation of words was accurate.

The speaker maintained an appropriate pace (not too fast or slow).

Comments:

Did the speaker’s pronunciation enhance or hinder understanding?

Any specific suggestions for improving clarity?

3. Engagement and Expressiveness

The speaker maintained eye contact with the camera.

Facial expressions matched the tone of the content.

The speaker used gestures effectively.

Comments:

Was the presentation engaging?

Any tips for improving expressiveness?

4. Body Language and Confidence

The speaker’s body language was confident and professional.

There were no distracting movements.

The speaker appeared comfortable and in control.

Comments:

Did the speaker’s body language add to the presentation’s impact?

Any suggestions for improving confidence?

5. Overall Impression

The presentation was informative and impactful.

The speaker effectively conveyed the topic’s importance.

Comments:

What was the most memorable aspect of the presentation?

How well did the presentation achieve its goals?

Open-Ended Feedback

One thing I really liked about your presentation was:

One area for improvement is:

A question I had while watching your presentation was:

Appendix C

Self-Monitoring Checklist for Revised Video Presentation

Student’s Name:

Date of Re-recorded Presentation:

For each item, check “Yes” if you addressed the feedback or made the change, or “No” if it still needs improvement. Use the comments section to note specific actions taken.

1. Content and Structure

Added examples or explanations to clarify main ideas. Yes ☐ No ☐ Comments:

Improved organization with a clear introduction, main points, and conclusion. Yes ☐ No ☐ Comments:

2. Clarity and Pronunciation

Spoke more clearly and at a steady pace. Yes ☐ No ☐ Comments:

Improved pronunciation of key words or phrases. Yes ☐ No ☐ Comments:

Used pauses effectively to emphasize important points. Yes ☐ No ☐ Comments:

3. Engagement and Expressiveness

Maintained better eye contact with the camera. Yes ☐ No ☐ Comments:

Improved facial expressions and tone to match content. Yes ☐ No ☐ Comments:

Used gestures more effectively to reinforce key points. Yes ☐ No ☐ Comments:

4. Body Language and Confidence

Displayed open, confident body language. Yes ☐ No ☐ Comments:

Minimized any distracting movements or habits. Yes ☐ No ☐ Comments:

Summary Reflection

1. What were the most significant improvements I made based on feedback?

2. What still needs further improvement?

3. One specific goal I have for future presentations is:

Appendix D

Characteristics of Poor and Excellent Communication Performances