Tatsuro Tahara, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan

Masayuki Odora, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan

Tahara, T., & Odora, M. (2025). Characteristics of repeat visitors to a university writing center in Japan: Applying a user database of reservations. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(1), 172–186. https://doi.org/10.37237/160109

Abstract

This study aimed to identify the characteristics of repeat visitors to a university writing center in Japan. Thus, the user database of reservations at the Waseda University Writing Center for the academic year of 2022 was analyzed. Descriptive statistics regarding the number of writers and sessions of repeat and one-time visitors were calculated using the reservation database. Additionally, a chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the differences in the reservation categories between the two groups of writers. The results indicated that in the academic year of 2022, 47.6% of writers were repeat visitors, while 79.9% of the respective sessions were conducted by repeat visitors. The analysis of reservation information revealed notable differences between repeat and one-time visitors in several session categories, such as the language of the paper and session, type of assignment, due date, school year, and what the writer wants to discuss. These findings provide detailed insights into writing center trends in Japan and suggest ways to address writers’ needs based on their frequency of visits.

Keywords: writing center, tutoring, repeat visitors, higher education, university in Japan

The number of writing centers at Japanese universities has been increasing, with new centers being established in the 2020s (e.g., Kwansei Gakuin University and the University of Tsukuba). However, research on writing centers has predominantly focused on supply side aspects such as establishment and initial operations (Delgrego, 2016; Johnston et al., 2010) and tutor development (Ota & Sadoshima, 2013). In contrast, studies on the demand side, specifically on the writers themselves, have been limited. Analyzing writers on the demand side is essential for ensuring the continued operation of writing centers.

Another avenue for research on writing centers is to focus on repeat visitors. Writing centers serve both one-time and repeat visitors. Understanding the differences between these types of writers can reveal trends in their behavior and inform strategies for effectively addressing their needs. Thus far, several studies have addressed the trends of writing center users. In international studies, Salazar (2021), through a meta-analysis, suggested that nearly one-third of students who visited writing centers exhibited improved writing performance compared to those who did not. Salem (2016) revealed that writing centers are more frequently used by women, students of color, English learners, and students with fewer inherited advantages. Building on Salem’s findings, Colton (2020) examined differences in perceptions of writing center services between users and non-users. The study found that non-users were often unaware whether the services were free, perceived writing centers as being less frequented by men, and believed that the primary users were individuals who struggled with writing. However, these studies primarily focus on comparisons between users and non-users, not the differences between one-time and repeat visitors.

In Japan, studies have also examined the trends of writing center users, including repeat visitors. Fukasawa (2013) reported that in 2011, approximately 40% of visitors to the Waseda University Writing Center were one-time users, while those who visited up to three times per semester accounted for approximately 82% of the total visitors. Nakatake (2022) examined the changes in writing products submitted by three repeat visitors at a university writing center in the Kanto area, focusing on writing indices including fluency, syntactic complexity, lexical diversity, and writing rating scores. Kobayashi et al. (2022) examined writers and their products, focusing on long-term repeat visitors at the Aoyama Gakuin University Academic Writing Center. They conducted a survey on repeat visitors and compared their writings with those of one-time visitors using a rubric. Furthermore, LaClare and Franz (2013) indicated that the majority of users at the writing center in their workplace were graduate students and faculty members.

However, studies conducted in Japan primarily focused on repeat visitors and did not investigate the trends of writers in comparison with one-time visitors. By comparing the differences between one-time and repeat visitors, it is possible to identify trends and determine the points that tutors should address, as well as what the center should prepare for and emphasize in tutor training. To address this gap, the current study aimed to identify the characteristics of repeat visitors by comparing them with those of one-time visitors. Thus, this study analyzed reservation data from the Waseda University Writing Center.

Background

Waseda University Writing Center

This study was conducted at the Waseda University Writing Center in Tokyo. Established in 2004, it was the first university writing center in Japan (Sadoshima & Ota, 2013). Modeled after North American writing centers, the center operates under the philosophy of fostering “independent writers” (Academic Writing Program, Waseda University, n.d.a), as encapsulated by the principle, “Our job is to produce better writers, not better writing” (North, 1984, p. 438). At the same time, this writing center has evolved uniquely within the Japanese context (Sadoshima & Ota, 2013).

An overview of the Waseda University Writing Center is as follows (Academic Writing Program, Waseda University, n.d.b): The center offers one-on-one tutoring, in which the writer and tutor engage in a discussion, referred to as a “session.” Each session is scheduled to last 45 minutes. The center supports all types of writing relevant to academic life and welcomes any stage of writing, including brainstorming, outlining, rough drafts, and final drafts. The center is open to the currently enrolled students and faculty members of Waseda University. The center offers sessions in both English and Japanese for the paper and session languages. The center is open on weekdays during the university’s academic terms. Writers are required to bring their papers to the beginning of the session. For face-to-face sessions, writers must print out their papers in advance. For online sessions, each writer must submit a paper to the tutor via Moodle at the beginning of the session.

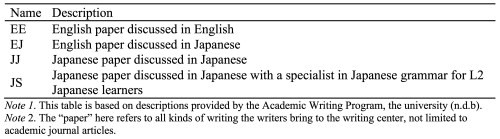

One of the distinctive features of the Waseda University Writing Center is the choice between Japanese and English for both the language of the paper and that used in the session (Table 1). Sadoshima and Ota (2013) noted that at the inception of the writing center’s operation, only sessions for English papers discussed in English were provided to the students in the newly established faculty, where most of the courses were taught in English; subsequently, the center expanded its services to include Japanese papers with discussions in Japanese, along with the JS (see Table 1 for description) session for Japanese language learners. Additionally, the center began supporting English papers discussed in Japanese (EJ) sessions.

Table 1

The Language of the Paper and Session in the Waseda University Writing Center

Note 1. This table is based on descriptions provided by the Academic Writing Program, Waseda University (n.d.b).

Note 2. The “paper” here refers to all kinds of writing the writers bring to the writing center, not limited to academic journal articles.

When making a reservation, the writer follows the procedures below:

3. Welcome sheet: The writer chooses each option in the reservation categories, such as the type of assignment, due date, stage of writing, school year or status, and what the writer wants to discuss. Additionally, the writer can freely fill out the details of the assignment or their concerns regarding the paper.

Thus, the reservation user data can be used to identify one-time and repeat visitors, thereby enabling a comparison of the trends in session reservation categories between both types of visitors.

Research Questions

Therefore, this study sought to answer the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: What is the number of writers and sessions for repeat and one-time visitors?

RQ2: How do the reservation trends differ between repeat and one-time visitors?

Methods

Data

This study used a user database of reservations at the Waseda University Writing Center. This study defined the repeat visitor period as one year and analyzed data from the 2022 academic year, covering the spring semester (April 8, 2022, to July 29, 2022) and the fall semester (September 28, 2022, to February 3, 2023). In the spring semester of 2022, 1,300 of the 2,367 available session slots (often referred to as “booths” at the Writing Center) were utilized, resulting in an operating rate of 54.9%. In the fall semester of 2022, 1,451 of the 2,528 booths were utilized, resulting in an operating rate of 57.1%. A total of 2,751 sessions (excluding cancellations) were analyzed. The user database of reservations was utilized with careful attention to research ethics, handling personal information with the utmost care, and ensuring that it was not used for purposes other than research.

Analysis

To address RQ1, this study initially identified repeat and one-time visitors in the user database to calculate the number of writers and sessions. In this study, a repeat visitor was defined as an individual who visited the center more than once per academic year, whereas a one-time visitor was defined as an individual who visited the center only once an academic year.

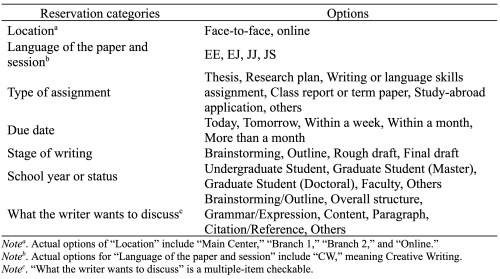

To answer RQ2, a chi-square test of independence was employed to examine the relationship between the frequency of visits (i.e., repeat or one-time visitors) and each reservation category, which included the location, language of the paper and session, type of assignment, due date, stage of writing, school year or status, and what the writer wants to discuss (Table 2). For reservation categories related to the frequency of visits, a residual analysis was also performed to determine which specific options were more or less frequently selected by repeat and one-time visitors. Table 2 lists the specific options for each reservation category. The analysis was performed using the “chisq.test” function in R (R Core Team, 2024). The ‘vcd’ package (Meyer et al., 2023) was used to facilitate the data analysis process, ensuring accurate computations and clear presentation of results (e.g., p-value).

Table 2

Reservation Categories and Options at the Waseda University Writing Center

Results

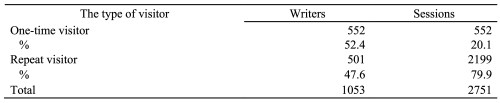

The Number of Writers and Sessions of Repeat and One-Time Visitors

Table 3 presents the numbers and percentages of writers and sessions of one-time and repeat visitors in 2022. In the academic year of 2022, 552 of the 1,053 writers were one-time visitors, and 501 were repeat visitors. In total, 2,741 sessions were observed, with 552 sessions for one-time visitors and 2,199 sessions for repeat visitors. As a percentage, 47.6% of the writers were repeat visitors, and 79.9% of the sessions were conducted by repeat visitors.

Table 3

The Numbers and Percentages of Writers and Sessions of One-time Visitors and Repeat Visitors in 2022

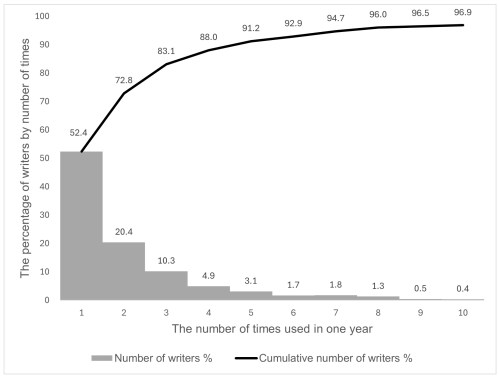

Figure 1 shows the percentage of users for each visit frequency within the academic year of 2022, ranging from 1-time to 10-time users. The highest number of visits by a single user was 63. A review of the proportions shown in the graph (Figure 1) reveals that one-time to three-time users accounted for 83.1%.

Figure 1

The Percentage of Writers per the Number of Times Used in 2022

Association of Reservation Category With the Frequency of Visits to the Writing Center

This study conducted a chi-square test of independence to examine the relationship between the types of writers regarding the frequency of visits (i.e., repeat or one-time visitors) and each reservation category. For the reservation categories found to be significantly related to the frequency of visits, residual analysis was conducted to examine which specific options were significantly different between repeat and one-time visitors.

Several operations were conducted on the data to perform the calculations. First, missing due date entries (one-time visitors: 2; repeat visitors: 5) were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, in the language of the paper and session, the options Creative Writing (CW) and Japanese paper discussed in English (JE) were also available, but were excluded because of their small number (CW session: one-time visitors: 0, repeat visitors: 2; JE session: one-time visitors: 1, repeat visitors: 4). This is because the recommended expected value in the cells of a chi-square test is at least five (Field et al., 2012). Consequently, six writers were excluded from the language of the paper and session analysis. Furthermore, regarding location, the number of face-to-face sessions was calculated for the main center and two branches. This was done because the purpose of this study was to compare face-to-face and online sessions and it was not necessary to examine the branches separately.

Table 4 presents a contingency table of the reservation categories and types of visitors (i.e., one-time or repeat visitors). The results of the chi-square tests of independence indicate that the frequency of visits (i.e., by one-time or repeat visitors) differed according to the language of the paper and session; X2 (3, N = 2745) = 14.57, p = .002. Similarly, the type of assignment differed according to the frequency of visits; X2 (6, N = 2751) =47.59, p < .001. Additionally, the due date was significantly associated with the frequency of visits; X2 (4, N = 2744) = 41.33, p < .001. Similarly, school year or status was significantly associated with the frequency of visits; X2 (4, N = 2751) = 49.38, p < .001. Finally, what the writer wants to discuss was significantly associated with the frequency of visits; X2 (6, N = 6677) = 19.17, p = .004. Contrastingly, chi-square tests of independence revealed that the frequency of visits (i.e., by one-time or repeat visitors) did not differ by location, X2 (1, N = 2751) = 0.15, p = .699; or by stage of writing, X2 (3, N = 2751) = 4.72, p = .194.

Table 4

The Contingency Table of the Reservation Categories and Types of Visitors

Regarding the reservation categories that were associated with the frequency of visits, Table 5 presents the residual analysis for each category. Standardized residuals exceeding ± 1.96 are considered significant at the 5% level, those exceeding ± 2.58 are significant at the 1% level, and those exceeding ± 3.29 are significant at the 0.1% level (Field et al., 2012; Table 5). Regarding the language of the paper and session, writers who chose the EE session were likely to be repeat visitors (z = 2.30, p = .021), whereas writers who chose the EJ session were likely to be one-time visitors (z = 3.45, p < .001). Regarding the type of assignment, repeat visitors were more likely than one-time visitors to bring a paper related to a thesis (z = 2.68, p = .007), journal article, or conference paper (z = 3.94, p < .001). By contrast, one-time visitors were more likely to bring a paper related to a writing or language skill assignment (z = 3.73, p < .001), class report or term paper (z = 2.00, p = .045), or study-abroad application (z = 3.39, p < .001). Regarding the due date, papers submitted by repeat visitors were more likely to require submission more than a month (z = 5.09, p < .001), whereas papers submitted by one-time visitors were more likely to require submission within a week (z = 5.34, p < .001). Regarding school year or status, repeat visitors were more likely to be doctoral students (z = 5.30, p < .001) and faculty members (z = 2.96, p = .003), whereas one-time visitors were more likely to be undergraduate students (z = 6.01, p < .001). Finally, regarding what the writer wants to discuss, repeat visitors were more likely to discuss the content of the paper (z = 2.51, p = .012), whereas one-time visitors were more likely to discuss citations and references (z = 2.74, p = .006) and others (z = 2.29, p = 0.02).

Table 5

Residual Analysis for Reservation Categories and the Type of Visitors

Discussion

This section presents a detailed analysis of the results of the RQs.

RQ1: What is the Number of Writers and Sessions for Repeat and One-Time Visitors?

The descriptive statistics indicate that in the academic year of 2022, 47.6% of the writers were repeat visitors, while 79.9% of the sessions were conducted by repeat visitors. Moreover, users who visited for the first to third time in one year accounted for 83.1%. These percentages are nearly identical to those reported in Waseda University’s past data from the spring semester of 2011 (Fukasawa, 2013), which indicates that one-time visitors accounted for approximately 60% (i.e., repeat visitors accounted for approximately 40%), and one-time to third-time users accounted for approximately 82%. However, it should be noted that repeat visitors did not always bring the same writing repeatedly each time. Repeat visitors occasionally brought different assignments or papers. Nevertheless, this study was able to present more detailed numerical data, including the total number of sessions, and identify any changes from past data.

RQ2: How do the Reservation Trends Differ Between Repeat and One-Time Visitors?

The chi-square test of independence revealed associations between reservation categories and types of visitors (i.e., repeat or one-time visitors). These categories include the language of the paper and session, type of assignment, due date, school year or status, and what the writer wanted to discuss. The residual analysis also revealed which specific options were selected by repeat or one-time visitors. Moreover, the chi-square test of independence indicated that the frequency of visits was not associated with the reservation categories of location or stage of writing.

Reservation Categories With a Difference Between Repeat and One-Time Visitors

First, regarding the language of the paper and session, there were discernible contrasts between the Japanese and English sessions. In the Japanese sessions, there was no difference between one-time and repeat visitors in either the JJ or JS sessions. Conversely, in the English session, the EJ session was utilized more frequently by one-time visitors, whereas the EE session was used more frequently by repeat visitors. As previously demonstrated, a distinguishing feature of the Writing Center at Waseda University is the availability of both Japanese and English options for the language of writing and sessions. This time, the distinction between the two language options became more pronounced. However, it is unclear why there were more one-time visitors at EJ and more repeat visitors at EE. One potential explanation for this phenomenon is that the more frequent use of EJ sessions by one-time visitors may be related to the nature of the sessions. In these sessions, writers who are not proficient in English can more easily take the initiative to lead discussions and discuss several topics (Sadoshima et al., 2009). However, these relationships require further investigation.

Subsequently, repeat visitors were found to be writers who often brought writing related to their research. Repeat visitors were more likely to bring papers related to their theses, journal articles, or conference papers than one-time visitors. Additionally, repeat visitors were more likely to be doctoral students or faculty members and to discuss content than one-time visitors. A previous study indicated that graduate students and faculty members comprise the majority of writing-center users (LaClare & Franz, 2013). In contrast to one-time visitors, this study shows that research-oriented writers are more likely to be repeat visitors.

Regarding the due date, one-time visitors were more likely to bring a paper that had to be submitted within a week, whereas repeat visitors were more likely to bring a paper that had to be submitted more than a month. This result suggests that, as is generally assumed, repeat visitors come to the Writing Center with more time before the deadline because they bring their writing to the center several times. Furthermore, if writers present their papers to the writing center before the deadline, tutors can review the content more thoroughly. This can result in greater satisfaction among writers, potentially leading to repeat visits. However, it is important to note that there is no difference between repeat and one-time visitors when the deadline is today or tomorrow, indicating that one-time visitors do not bring their writing just before the deadline.

Additionally, study-abroad applications were more frequently chosen by one-time visitors. This phenomenon is likely attributable to the fact that the majority of students who apply to study-abroad programs are undergraduate students at the university, and these students utilize the writing center only once. Consequently, the use of the writing center may be influenced by external factors in the university environment.

Furthermore, citations and references were selected more frequently by one-time visitors. These one-time visitors who visited the Writing Center had difficulty citing sources or creating reference lists for their writing assignments or English language assignments. In other words, the Writing Center has become a “last resort” for those who lack the knowledge of how to write citations and references. This is a positive aspect, as the Writing Center can help students in need. However, to some extent, the format for writing citations and references is subject to conventions in the field of research. To address the large number of students seeking guidance on citations and references, the Writing Center could organize a workshop on citations and references of major styles (e.g., APA, MLA, IEEE), as presented by McKinley’s (2011) group workshop. In this sense, tutors in writing centers can develop a more flexible and adaptable approach for writers in need of citation and reference support sessions.

Reservation Categories With no Difference Between Repeat and One-Time Visitors

Regarding location, there was no difference in preference for online versus face-to-face sessions between repeat and one-time visitors. This result suggests that regardless of whether the writers were one-time or repeat visitors, they used writing centers in an easily accessible way. In other words, one-time visitors were neither more likely to utilize the writing center face-to-face, nor were repeat visitors more likely to favor it online.

Regarding the stage of writing, there was no significant difference between repeat and one-time visitors. This result is noteworthy given that there was a difference in due dates depending on the frequency of writers’ visits to the writing center. In other words, although repeat visitors were more likely to visit the writing center with more time to meet deadlines, they did not bring their writing from the beginning stages, such as brainstorming and outlining. One potential explanation for this phenomenon is that repeat visitors bring the same papers repeatedly to refine their writing rather than revisiting the center with the progress of sentences or paragraphs every time. An alternative explanation could be that even repeat visitors are unaware that they can visit the center at any stage of writing. This point may necessitate another approach to publicize the Writing Center’s services throughout the university.

Conclusion

This study analyzed the user data of reservations at the Waseda University Writing Center and calculated the number of writers and sessions of repeat and one-time visitors. Moreover, a chi-square test of independence and residual analysis were employed to ascertain the specific options that differ between the two types of visitors.

The strength of this study lies in its use of reservation data, which enabled us to gain a more concrete and numerical understanding of the actual situation of repeat visitors. The significance of this study is further underscored by the comparison of repeat and one-time visitors, which offers a more thorough analysis. For instance, repeat visitors are writers who bring research-related writing. Additionally, there was no difference in the language of the papers and sessions in Japanese; however, in the English sessions (EE and EJ), the tendency differed depending on the frequency of visits to the center. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to provide a detailed analysis of user data on reservations at a writing center in Japan.

However, this study had some limitations. The results are based on data obtained from a single university. Moreover, this study focused on analyzing repeat visitors within an academic year. However, it did not include analyses specific to either the spring or fall semester, nor did it address repeat visitors across periods exceeding one year. Some students may visit repeatedly for more than a year during their school years. Furthermore, although reservation categories were identified, not all of the reasons why these tendencies differed were fully identified. This issue should be addressed in future studies.

Despite its limitations, this study has contributed to the understanding of the trends in writing center use by repeat and one-time visitors and has provided information on the status of writing centers in Japan. Further research is required to elucidate the reasons for the differences in reservation categories between one-time and repeat visitors. Moreover, an analysis of reservation data from other universities in Japan could provide insights into whether similar trends exist, thereby contributing to the accumulation of knowledge regarding writing centers in Japan.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the staff members of the Global Education Center, Waseda University and Waseda University Academic Solutions Corporation for their assistance in preparing the user database of reservations at the Waseda University Writing Center.

References

Academic Writing Program, Waseda University (n.d.a). What is the writing center? https://www.waseda.jp/inst/aw/en/about/what

Academic Writing Program, Waseda University (n.d.b). Using the writing center. https://www.waseda.jp/inst/aw/en/about/using

Colton, A. (2020). Who (according to students) uses the writing center?: Acknowledging impressions and misimpressions of writing center services and user demographics. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 17(3), 29–51.

Delgrego, N. (2016). Writing centers in Japan from creation until now: The development of Japanese university writing centers from 2004 to 2015. The Journal of J. F. Oberlin University, 7, 15–29.

Field, A., Miles, J., & Field, Z. (2012). Discovering statistics using R. Sage.

Fukasawa, T. (2013). Uketsuke [Reception]. In S. Sadoshima, & Y. Ota, (Eds.), Principle and practice of writing tutoring (pp. 230–235). Hitsuji Shobo.

Johnston, S., Cornwell, S., & Yoshida, H. (2010). Writing centers in Japan. Osaka Jogakuin Daigaku Kenkyuu Kiyou, 5, 181–192.

Kobayashi, N., Nakatake, M., & Shimada, H. (2022). Keizokuteki na Riyou ga Mizukara Kakuchikara wo Sodateru Aoyama Gakuin University Writing Center [Aoyama Gakuin University Writing Center, where continuous use fosters the ability to write independently]. In C. Inoshita (Ed.), Writing discipline to encourage inquiry thinking through deep active learning (pp. 213–228). Keio University Press.

LaClare, E., & Franz, T. (2013). Writing centers: Who are they for? What are they for? Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.37237/040102

Meyer, D., Zeileis, A., Hornik, K., & Friendly, M. (2023). vcd: Visualizing Categorical Data (R package version 1.4-12) [Computer software]. CRAN. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vcd

McKinley, J. (2011). Group workshops: Saving our writing centre in Japan. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 2(4), 292–303. https://doi.org/10.37237/020406

Nakatake, M. (2022). Exploring longitudinal changes in L2 writing of Japanese EFL students of a writing centre, Language, Culture, and Society, 20, 31–45. https://glim-re.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/5525/export/json

North, S. (1984). The idea of a writing center. College English, 46, 433–446. https://doi.org/10.58680/ce198413354

Ota, Y., & Sadoshima, S. (2013). Tutor training and PAC analysis of two tutors’ awareness towards tutorial sessions: Waseda University Writing Center’s case. Waseda Global Forum, 9, 237–277.

R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

Sadoshima, S., Ota, Y. (Eds.). (2013). Principle and practice of writing tutoring. Hitsuji Shobo.

Sadoshima, S., Shimura, M., & Ota, Y. (2009). Effectiveness of tutoring English writing in Japanese: NNS tutors helping NNS writers at Waseda SILS Writing Center, Waseda Global Forum, 5, 57–71. https://waseda.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/25012

Salazar, J. J. (2021). The meaningful and significant impact of writing center visits on college writing performance. The Writing Center Journal, 39(1), 55–96. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1958

Salem, L. (2016). Decisions…decisions: Who chooses to use the writing center? The Writing Center Journal, 35(2), 147–171. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1806