Danica Anna D. Guban-Caisido, University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3933-6383

Guban-Caisido, D. A. D. (2025). A sequential case study on advising in language learning from the emergency remote setup to the transition to the new normal. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(1), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.37237/160108

Abstract

Advising in Language Learning (ALL) was implemented as a two-phase, sequential case study in a foreign language department at a state university in the Philippines. The first phase, piloted at the height of the pandemic in 2020, aimed to utilize advising as a means of psychosocial intervention for first-time self-access learners. It served as a form of action research to respond to the needs of students who had to navigate language learning despite the harsh external conditions brought about by the pandemic. The second phase was implemented during the transition to the in-person classes, when the university had started to enforce blended modes of learning. To take advantage of blended learning, the advising sessions were conducted at regular intervals throughout the semester as a complementary didactic tool to the flipped classroom. A juxtaposition of the two phases of advising in different academic years and in different learning contexts proves that despite operating on the same principles and utilizing the same methodologies, advising sessions yielded differences in terms of their objectives, emerging themes, challenges, and essence. This synthesis report highlights the flexible nature of advising that can be utilized in a variety of contexts and can withstand however form of modality change.

Keywords: ALL, language learning, emergency remote setup, flipped classroom, new normal

Advising in Language Learning is not a widespread practice among Philippine universities. Despite the number of local secondary and tertiary institutions offering courses on a variety of additional and foreign languages, there have yet to be formally documented reports on the concrete practices of academic support that are specifically tailored towards foreign language learners in the country. This lack of visibility may be attributed in part to the fact that most Philippine educational institutions have always adhered to more traditional language learning structures such as face-to-face learning and instruction prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Self-access centers and self-access language learning modalities were few and far in between. As such, a literature review on the practice in the country yields extremely marginal results that are insufficient to support its existence and praxis.

Advising in the context of language learning, also coined as Advising in Language Learning (ALL), is the practice of working directly and closely with a student to promote language learning autonomy (Carson & Mynard, 2012). Through listening tools such as co-constructed dialogue (Karlsson, 2012; Mozzon-McPherson, 2012) that promotes reflective thinking and metacognition among students, advising sessions aim to promote deeper level thought processing and critical review of one’s own learning. To be able to achieve this, reflection is a key catalyst in the advising sessions. Drawing from Mezirow’s (1991) transformation theory of widening the worldview to accommodate and assimilate new perspectives in learning, Kato and Mynard (2016) enumerate the following activities and analysis that result in a shift in outlooks among the students: (1) analysis of the content; (2) analysis of the process; and (3) analysis of the premise. All said, analyses require proper scaffolding and guidance from a competent language adviser.

The researcher first implemented advising in a foreign languages department at a state university in the Philippines in early 2019, in the hopes of introducing a brand of linguistic academic support that will reduce the knowledge gap and hopefully proliferate the practice within a particular foreign language department. While there have been challenges in its preliminary implementation in the in-person, face-to-face modes of practice, the extraordinary global circumstances and the consequent pedagogical implications brought about by the sudden rise of COVID-19 cases across the world proved to be the most daunting challenge of all.

Literature Review

The Philippine Context: The Emergency Remote Set-Up

With the detection of the virus in the country in March of 2020 came rather drastic measures from the Philippine government. To mitigate the further spreading of COVID-19, several extreme efforts had to be made and instigated, which included conforming with strict health guidelines and safety protocols and implementing social distancing measures which involved enforcing entire cities under lockdowns (Guban-Caisido, 2020). Observance of such extreme conditions bore heavy pedagogical implications as most educational institutions either had to adapt to remote learning emergency setups and their respective strategies or face the possibility of permanent closures altogether. Given the case, most schools took to the online learning mode of teaching and learning utterly ill-equipped, with no a priori background of the proper implementation of online pedagogy nor adequate time for materials preparation, teacher training, and familiarization with the breadth of platforms available to conduct the classes.

Such was the predicament faced by the same university where the initial advising sessions were held by the researcher. From the in-person setup, classes were then entirely shifted to the online mode. However, a general lack of preparation from among the stakeholders stirred unease and dissatisfaction among the university population prompting the need to adhere to the remote, asynchronous mode of learning to accommodate materials preparations, to buy time for course redesigns, and to resolve existing technical issues within the university (University of the Philippines, 2020). This move, however, quite literally left the students to their own devices in the middle of the semester. This precipitous shift from the traditional to the online setup to self-access learning proved to be exceptionally stressful for the students, not only from the Philippines but from all over the world, as supported by several studies (Gao & Zhang, 2020; MacIntyre, et.al, 2020; Moser, et.al, 2021). This condition further necessitated conducting advising sessions among the first-time self-access students, the change of modalities notwithstanding.

ALL in the New Normal

The university gradually transitioned to the blended mode of learning towards the end of 2022, owing to the improving situation of COVID cases in the country (Subingsubing, 2022). After two years of classes conducted fully online, teaching and learning resumed to partial face-to-face classes following one of the three learning models mandated by the university: (a) fully online, (b) blended block learning which combined independent online study and intensive face-to-face sessions, and (c) classic blended learning which combined independent, asynchronous study and face-to-face sessions.

The utilization of ALL in the online setup is supported by literature. While it works on the principle of an adviser meeting with a student for a discussion of language learning progress and feedback, the modality by which it is conducted may differ, as it may also be conducted in open and distance environments (Davies, et al., 2020; Hurd, 2001; Ruiz-Guerrero, 2020), and even electronic environments (Reinders, 2006).

While there are a variety of theoretical perspectives from which ALL may be explored and practiced, the fact that it remains sociocultural will always be relevant. Lantolf and Poehnoer (2008) state that viewed from a sociocultural perspective, language functions as a tool that accounts for the multifaceted aspects of the learner’s life, which includes their social, historical, psychological, and, more importantly, contextual situations. Hence, the fact that ALL tends to surface the students’ concerns other than their academics is not surprising, especially in the light of student-led discussions. In fact, its use as a form of psychosocial support is by no means a novel practice. Initially conceived as a form of reflective dialogue between an adviser and a student with the aim of promoting learner autonomy, ALL takes into consideration the student’s personal circumstances, including his objectives, interests, and other expressions of identity. The roots of the practice grounded in psychology, counseling, and the psychology of language learning makes it inherently ‘helping’ by nature (Mynard, et Al., 2021), especially in terms of its focus on the student and his needs.

The Flipped Classroom

With the propensity to promote superior knowledge and skills among students to make them competent in the working world, most academic institutions prefer to adhere to the traditional one-size-fits-all mode of pedagogy to accommodate quantity over quality of learning, as focusing on quality or ‘depth’ also means exposing students to less of the curriculum (Conley, 2020). This partiality to breadth over depth leads to students being unable to cope with the pace of the classes, often at the expense of foregoing authentic understanding of the concepts just to survive the standardized tests and assessments implemented by most schools. This focus on orthodox and prescriptive learning not only does not consider individual learning needs, but also fails to account for the active role that the students are expected to play in their own studies. Hsieh et al. (2022) affirm that conventional instruction tends to promote lower order thinking skills such as rote memorization and basic grasping of the concepts.

Among the more modern pedagogical approaches that aim to combat passivity in learning is the flipped classroom approach. Defined as a didactic practice wherein “events that have traditionally taken place inside the classroom now take place outside the classroom and vice-versa” (Lage et al., 2000). In essence, it is a literal flipping of the classroom: students are expected to have learned the lessons already at home prior to going to class which is then dedicated to interactions, drills, and feedback. One of the main advantages of the practice is freeing up time supposedly used for traditional lectures and class discussions and dedicating these instead to more practical applications and refinement of what has been learned.

Method

Context

The sequential case study was conducted in two phases that spanned two years in total. The first phase was conducted purely online during the height of the pandemic in 2020. The second phase was conducted during the blended mode of learning as implemented by the university in a study in 2022. The implementation of ALL in different contexts necessitated a review and juxtaposition of the changes that emerged in terms of its objectives, challenges encountered, and its essence. Hence, this study wishes to answer the following questions:

- How do the objectives and emerging themes differ in the implementation of ALL in the online and blended learning environments?

- What are some of the significant challenges encountered in the implementation of ALL in the online and blended learning environments?

- How do the contextual differences mold the essence and function of ALL?

Phase 1: ALL in the Online Mode

Participants

With the peculiar state of circumstances, especially in the emergency remote setup in education in the Philippines in 2020, the researcher utilized convenience sampling, drawing volunteer participants (n=10) from a basic language class. These students were from diverse programs, of ages ranging from 19-22, and were composed of both males and females who were all enrolled in an A1 Italian class. The call for volunteer participants was sent through email, through which the researcher also communicated the need for Informed Consent.

Data Collection

For Phase 1, ALL functioned not only as a means of linguistic support, but also for psychosocial intervention. Its goals had to be restructured to accommodate the other needs of the students given the conditions, going beyond tracking their language learning progress and reflective dialogues to include well-being checks, understanding student needs, and fostering psychosocial support. Furthermore, the very modality by which it was being conducted had to shift as well, from the physical to the online sphere.

For the data collection for Phase 1, Zoom was used for the advising sessions, which lasted 20 minutes for each student. The sessions were recorded with the participants’ consent and were transcribed using the Zoom’s built-in transcription function. The data collection for Phase 1 of the study was conducted in two weeks, given the extraordinary circumstances of the university context.

Data Analysis

The data from the recorded advising sessions were revisited and the transcriptions were downloaded for the purpose of thematic analysis. Each transcription was presented as initial, axial, and thematic coding, following the guidelines by Braun and Clarke (2006) for thematic analysis. The codes were then categorized according to the four emerging themes: personal, academic, technical, and economic concerns.

Findings and Discussion

Four major themes emerged from the online advising sessions with the students, with all experiences revolving around the implications of COVID-19 in the different aspects of their lives. Figure 1 summarizes the emerging themes from Phase 1 of the study.

Figure 1

A Summary of the Themes Emerging From Phase 1 of the Study Conducted in 2020

As a method of reflective learning, ALL was able to extract student experiences with the academic difficulties encountered with self-access learning. As students belonging to an institution that operated primarily on traditional approaches, the shift to online and self-access proved to be demanding for the students. There was an overall dissatisfaction with the way the guidelines were handed to the students, with the decisions being mostly transmissional and without prior consultations with the other stakeholders, such as the student body. Furthermore, the lack of procedural guidance and feedback from the part of the teaching personnel also added to the burden of self-access; having to learn foreign languages without proper supervision was difficult enough in itself but was even more compounded by misdirection. All these misgivings gave rise to a lack of self-confidence among the learners in pursuing their learning in the self-access mode, as evidenced by the student responses throughout the advising sessions. The fact that they were learning a foreign language also added to the difficulties of self-access learning: the students held a view that language learning was a more intimidating activity compared to other classes due to its nature, which necessitated a lot more scaffolding in terms of both input and output. As one student succinctly narrated: “Language is so different from the other subjects.. there are so many factors that should be practiced in the classroom because it is skill-based”.

For the most part, personal problems referred to tensions that arose from being confined with family members for months on end; a problem that was rampantly observed among students who lived away from home for most of the semester. Furthermore, there were students who deliberately chose to live by themselves prior to the pandemic due to abrasive family relationships. The sudden reintegration into the family home and dynamics resulted in tensions that could not be easily alleviated due to the physical constraints and the social distancing measures in place throughout the year. For some students, filial responsibilities also added to the list, given how some of them had to be the designated pass holders during the time the quarantines were still in place. Some were errand runners or caretakers within their families. This made juggling responsibilities challenging, and as such, attending to their academic needs became arduous. As one student narrated: “My academics are the last thing on my mind.” Even grimmer among problems under this theme was the loss of family members and friends due to COVID-19.

A third angle included the technical difficulties arising from the internet connectivity issues in the Philippines. The shift to the online delivery of teaching and learning was totally unanticipated, leaving most households unprepared in terms of their electronic device preparedness and internet connectivity status. Furthermore, most households, especially those with a larger number of family members residing under one roof, had to make do with sharing data and wifi connectivity, resulting in even slower connection and internet activity. The shift from physical to work-from-home settings for the employed members of the families also contributed significantly to data and wifi shortages among households. While this is a rampant problem for the students who had to attend synchronous sessions, the same could be said for the students who had to access their class materials from the university’s LMS or other sites as supplementary resources, as accessing and downloading also took a significant chunk of storage space.

Another dimension exposed by the ALL sessions was problems consisting of displacement, unemployment, and lack of purchasing power- all of which were socioeconomic effects of the pandemic. Many students had family members who were either displaced or terminated from their jobs due to the harsh safety protocols that temporarily ceased the operations of several establishments, and which resulted in poor economic conditions for the households. Moreover, working students who have previously been earning had to face unemployment, causing a lack of purchasing power in upgrading their electronic devices which have since become necessities to continue with education.

The Challenges of the Pilot Online ALL Sessions

The online implementation of ALL, however brief, proved to be successful as a means of psychosocial support among learners during the liminal period from the changes necessitated by the onset of the pandemic and throughout the many transitions that came thereafter. Despite its success, however, several challenges were encountered. The abrupt shift of the ALL sessions to the online mode was not an easy feat. Despite having conducted this in the past, the researcher had yet to initiate an online version of the traditional advising, which gave rise to several issues. The most pressing among these was internet connectivity. In fact, this problem became so rampant during the height of COVID-19 that some classes had to be done asynchronously through printed course materials and collated supplementary materials. Given the case, participation in the online ALL sessions had to be on a voluntary basis. This meant that only those whose internet connection was stable enough to sustain a twenty-minute recorded conversation via Zoom participated to consider the technical capabilities of the students.

Another problem that emerged was student engagement. After having been left to self-study with the materials through the university’s Learning Management System and its equivalents, the students had yet to reintegrate into the presence of their professors, albeit virtually. This posed a problem in terms of engaging the students to discuss not only their language learning progress, but more so to converse about their current well-being and individual state of affairs. Thankfully, most students were able to warm up throughout the course of the sessions, enabling proper dialogue between the adviser and the students

Aside from the cases of voluntary participation due to internet connectivity issues and student engagement, feedback from the students pointed to misgivings in terms of the proper planning and implementation, spacing of the sessions, and student profiling to better determine student demographics.

Congruent with the lack of planning and ample preparation time for holding online classes, the online ALL sessions were not thoroughly implemented to adjust to the changes of the then actual condition. As the activity was conceptualized only as a form of temporary intervention for learning progress tracking and well-being check, several necessary steps were missed, causing the program to seem like it cut corners.

For one, there had been no time dedicated to getting to know the students a little deeper through proper profiling, history, and demographic noting. As the ALL sessions were held in the middle of the semester, the objective was to immediately check on their learning progress and inquire about their personal, immediate circumstances. Their previous language backgrounds and learning histories and trajectories were not given priority given the time constraints.

The implementation of the ALL sessions rather left much to be desired as well. The adviser utilized the call function of Zoom in consideration of the technical difficulties of the students, foregoing the advantages of having used the video functions instead, where a more personal connection could have been fostered. Furthermore, the time set for each student (20 minutes) was barely adequate to cover the breadth of information gathered from each individual. While this duration would have been sufficient previously in terms of discussing only language progress and challenges, the addition of more topics to cover, such as in the case of psychosocial issues, should have informed the decision for additional time for discourse.

Lastly, the spacing of the sessions was something to improve on. Each student was consulted twice throughout the period, but no criteria were set regarding the choice of the time frame between each session. This could have been explained in further detail to the volunteer participants. All these challenges encountered during the implementation of the online ALL sessions were taken into consideration prior to advancing toward the second phase of the project.

Phase 2: ALL in the Blended Learning Mode

Context

The university eventually transitioned to the blended mode of learning towards the end of 2022 due to improving conditions, following one of the three learning models mandated by the university: (a) fully online, (b) blended block learning which combined independent online study and intensive face-to-face sessions, and (c) classic blended learning which combined independent, asynchronous study and face-to-face sessions.

The concept and methodology of the flipped classroom were introduced at the beginning of the semester to inform the students of the possible novelties to the didactic arrangements and to set class expectations. Operating on the workday schedules of the university, the first two days were assigned as independent study sessions. These days were dedicated to personal reading and study wherein they were given liberty to digest the materials and resources provided for them and to utilize whichever form of realia that catered to their interest. The following days were dedicated class hours which were used for application, drills and practice, interaction, and feedback, more than traditional classroom discussions.

Participants

With these changes of modality in place, the second phase of ALL was implemented in a smaller language class in the same state university as an extension of the pilot online ALL program first carried out in 2020. Following the sampling method utilized in Phase 1, Phase 2 also used convenience sampling, taking volunteer participants (n=5) from an A2-level Italian class. The class was composed of males and females, ages 19-22, from different degree programs. The students were asked to comply with an Informed Consent form. To take advantage of the blended mode of learning, the researcher implemented the flipped classroom approach and reinforced this with ALL.

The ALL sessions were scheduled four times throughout the semester at regular intervals. At the end of the semester, the students were asked to answer an open-ended questionnaire regarding the ALL experience, which also gauged their perception of whether ALL complemented the flipped classroom.

Data Collection

Similar to Phase 1 of the study, Phase 2’s advising sessions were held via Zoom’s video call function. All advising sessions were recorded with the students’ consent, and the transcriptions of each conversation were downloaded directly from Zoom for documentation. The data collection for Phase 2 of the study lasted longer, taking up a whole semester.

The primary objective for the implementation of ALL in the transitionary phase to the blended mode of learning was, first and foremost, for process improvement of the pilot online ALL sessions. Drawing from the feedback of the participants from the pilot online ALL sessions, ample planning, spacing, history taking and profiling, and proper implementation were all taken into consideration in the second phase of the ALL sessions.

The secondary objectives were in congruence with the principles of the flipped classroom approach: to promote autonomy, competence, and relatedness among the students. As the participants were a newer batch of students who began their language learning online and who were gradually easing into the return to in-person classes, there was a lesser need for scaffolding and a greater push towards more authentic and autonomous learning.

Data Analysis

For consistency, Phase 2 of the study replicated the exact data analysis process from Phase 1: each recorded advising session was revisited, and transcriptions were downloaded and analyzed for thematic analysis. Codes were presented in terms of initial, axial, and thematic coding, following the guidelines by Braun and Clarke (2006) for thematic analysis.

Findings and Discussion

While the discussions during the ALL sessions remained student-led, the content of the students’ responses was noticeably very different from when they were conducted at the height of the pandemic. Perhaps attributable to then ameliorating conditions in terms of documented COVID cases, the focus of the discussions had been less on personal and economic considerations and instead was geared more towards their academic concerns.

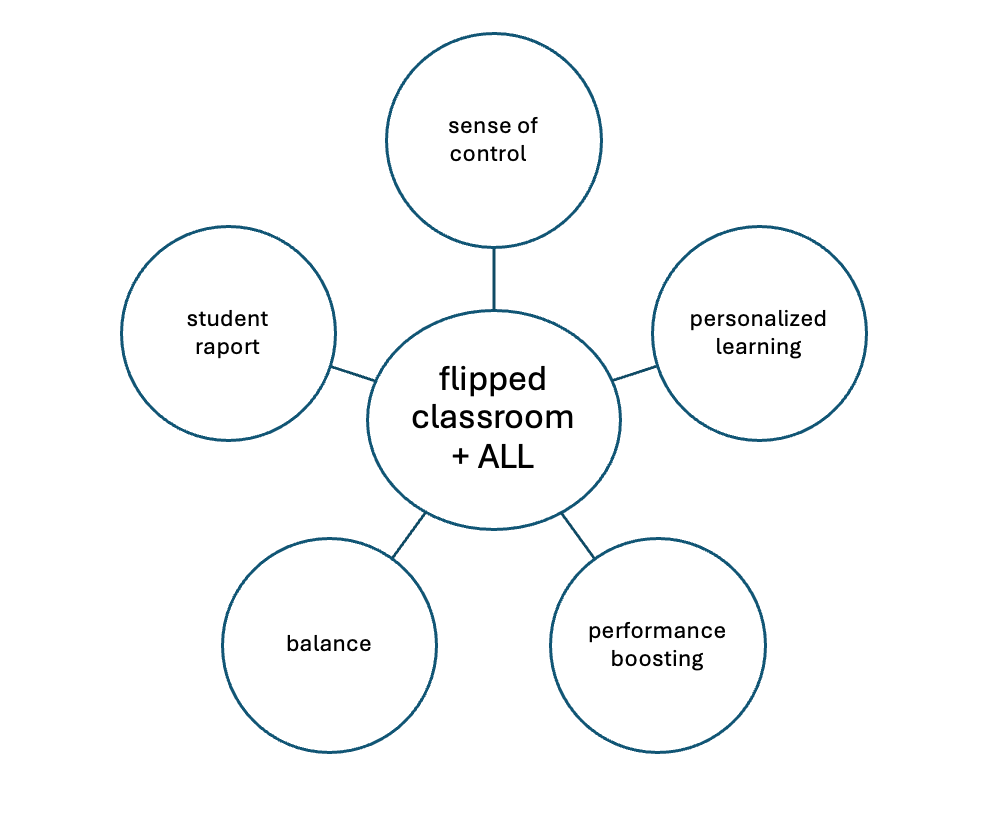

Following a textual analysis of the student responses, the following themes emerged from the analysis: sense of control, personalized learning, performance boosting, balance, and a fostering of student rapport. Figure 2 summarizes the said themes.

Figure 2

A Summary of the Themes Emerging From Phase 2 of the Study Conducted in 2022

There was an overall perceived positive and direct relationship between the flipped classroom and ALL. There was a consensus on ownership and accountability in terms of their learning, especially considering the flipped classroom method, which reinforced a sense of control. As the flipped classroom emphasized independent study, students were not pressured to understand concepts because they could learn these in their own time and pace and could validate their understanding through the dedicated class hours intended for practice, interaction, and feedback. This also provided ample time for mental preparation that fortified a sense of control of their own learning. The positive perception of self-learning resonated with the findings of Hung (2015), who stated that the use of the flipped classroom helped in improving not only academic performance but also participation levels and learning attitudes.

The combination of the flipped classroom and the regularly set ALL sessions throughout the semester gave the students a sense of personalized learning. Aside from being given enough time to digest the language lessons on their own, they were also greatly guided by the ALL sessions every now and then.

Despite the autonomy enforced by the flipped classroom, ALL helped in scaffolding, ensuring that while the students were expected to be independent learners, they were still guided towards the right path by the adviser. This promoted a feeling of importance in that the focus of every ALL session was the individual student only. A further advantage of the ALL was in redirecting the students through reflective dialogue which aided in metacognition.

A positive change in attitude towards the flipped classroom was among the key products of the combination of the flipped classroom and ALL. Fostering autonomy through the flipped classroom while maintaining supervision through the ALL sessions reinforced class performance. For one, there is more tailor-fit feedback for every student during the ALL sessions, which allowed them to notice, acknowledge, and rectify the errors they might have committed, resulting to a more reflective and critical understanding of their own learning. Additionally, ALL helped bridge the gap between thinking and doing in the target language, given that the reflective dialogues in ALL are not only solutions-focused, but also abide by the principles of Vygotsky’s (1978) Zone of Proximal Development, where one’s range of skill may be developed to its full potential with proper guidance at each level of development. As one student testified: “my speaking skills greatly improved after the consultation sessions because it helped unlock parts of my brain that let me convert… thinking into speaking, and eventually the two fuse together and it is absolutely divine whenever it happens.”

A good rapport between students and teacher/adviser was also maintained throughout the semester. The four elements of rapport such as behavioral expectations, face conditions, emotional reactions, and interactional wants and goals (Spencer-Oatey, 2011) were all observed during the ALL sessions. Despite the clear bifurcation imposed by the inherent authority of the teacher-advisor in the language classroom, there was reciprocal respect, and the recurring conversations were based on the philosophies of equity and association.

Overall, the students perceived the scaffolding and guiding doctrines of ALL as a complementary tool to the autonomous, self-directed nature of the flipped classroom. The implementation of the flipped classroom in complement with ALL meant more time for observation of student progress, needs assessment, and solutions-focused dialogues. The freer and more flexible time during in-class hours also equated to more opportunities for adviser and peer interactions.

The Challenges of ALL as a Complement to the Flipped Classroom

Considering the student feedback from the first phase of the study, the researcher aimed to improve the implementation of the second phase by carefully planning the duration and intervals of each session, working around the mandated university’s academic calendar to accommodate student schedules. As such, the dates for each session were fixed. However, untimely and unanticipated deviations from the academic calendar also called for interruptions in the advising sessions, posing a challenge in maintaining the designated schedules for the semester.

In addition to considering the academic calendar, the blended learning mode and the gradual transition to the in-person classes also meant more personal schedules to navigate. As such, both the adviser and the students had to deliberately make time for the ALL sessions, at times having to squeeze them in between other agendas.

Conclusion

ALL was used in different contexts and in different academic years in the sequential case study presented in this paper. In both contexts, advising worked on the same principles and applied the same methodologies, and yet differences were observed in different fundamental elements. ALL underwent notable changes as demonstrated and embodied by the following research questions:

- How do the objectives and emerging themes differ in the implementation of ALL in the online and blended learning environments?

- What are some of the significant challenges encountered in the implementation of ALL in the online and blended learning environments?

- How do the contextual differences mold the essence and function of ALL?

Figure 3 below summarizes the juxtaposition of the two phases of advising as implemented in the two-phase case study.

Figure 3

Juxtaposition of the Two Phases of ALL in Different Contexts

In terms of its objectives, Phase 1 was conducted as a psychosocial intervention for the students. As mentioned, the voluntary student participants underwent a series of transitions within one semester due to the instability caused by the rising numbers of COVID-19 cases in the country. Hence, the students went from experiencing learning from the traditional, face-to-face classes to the online, synchronous mode of learning, and going into remote or self-access learning. Throughout this period, there had been no proper procedural guidance with regard to the transitions nor was there ample time for materials and platform preparation on the side of the teachers, which caused significant stress on all concerned. As a form of action research, Phase 1 was conceived as an intervention. While it originally aimed to track the learning progress of each student given the self-access mode, more themes emerged from the conversations, going beyond the academic sphere of language learning. Phase 2, on the other hand, had the privilege of being utilized purely for academic concerns, given the improving situations in terms of COVID-19 cases at the time it was conducted. In a way, the advising sessions that were set at regular intervals throughout the interim semester greatly aided in handholding the students toward transitioning to the new normal mode of learning. As a form of complementary tool to assist in the flipped classroom, the consistent advising sessions helped in scaffolding and in fostering a renewed sense of autonomy among the students.

The emerging themes drawn from the advising sessions also differed greatly in terms of the content of the discussions, shifting from personal and socioeconomic grievances for Phase 1 to more academic concerns during Phase 2. The voluntary student participants from the first phase of the study had a more varied repertoire of concerns and grievances, including personal, academic, technical, and economic. It is notable, however, that while academic concerns remain, they took a backseat throughout the duration of the advising sessions, as the students felt that their academic concerns were the least of their worries. This phenomenon is not only understandable but is reflective of the context of the students. Applying Ushioda’s (2009) person-in-context view of the language learner affirms that the learner and the context are mutually constitutive, such that neither the learner nor the context are in isolation, and hence, will always influence each other. Congruent with the objectives of Phase 2, the emerging themes from the advising sessions yielded mainly perspectives on the complementarity of advising with the flipped classroom and mostly academic concerns. As a form of didactic tool meant to accompany a pedagogical approach that is geared towards stimulating learner autonomy, the advising sessions proved to be a reinforcement of the guiding principles of self-directed learning and hence promoted a strong sense of control and ownership among the students.

The challenges encountered during the implementation of the advising sessions at different points and different contexts proved to be very diverse. For the first phase, the challenges were more telling of the inconsistency in terms of implementation, lack of proper planning, and incomplete adherence to the process of advising. Aside from these, technical problems were also recurrent, which prevented compulsory advising for the chosen class. Instead, only those students whose internet connections were stable enough to hold a twenty-minute Zoom conversation were tapped as participants to consider the technical concerns of the class. Furthermore, engagement became a primary concern, as it proved to be challenging to encourage the students to share during the initial parts of the sessions. With Phase 2, the challenges were attributable to time and logistics issues. As the university was slowly transitioning into the new normal or the blended mode of learning, more leeway had to be given in terms of arranging the schedules of the advising sessions throughout the semester. Individual schedules also had to be considered on top of the university academic calendar and its deviations. It was necessary to deliberately dedicate time to the advising sessions, both on the part of the students and the adviser.

The essence of advising also differed for both contexts. For Phase 1, its core was care and support, living to its humanistic and therapeutic nature of focusing on the well-being of the learner by providing assistance and catering to the students’ psychosocial needs by means of student-centered dialogue that is meant to be reflective and solutions oriented. For Phase 2, the essence of advising was as a form of academic support and scaffolding mechanism in the passage to more autonomous, self-directed learning.

The juxtaposition of the two case studies proves the pliability and adaptability of advising in learning. As a form of psychosocial support, it can be an avenue to concerns that are beyond academic. It promotes well-being among the students through an analysis of their individual needs and differences, and an understanding of their varying contexts which influence their motivations, behavior, and performance. As a didactic tool, it is malleable enough to supplement and complement other existing forms of pedagogical practice, bridging the gap towards independent learning by means of incremental scaffolding.

Advising is a pedagogical tool that can accommodate a breadth of concerns, all the while promoting reflective thinking through intentional, critical dialogue, which evolves into the end goal of education: transformative action. Furthermore, it is a pedagogical practice that can be used in a variety of contexts that can withstand the test of time, as its flexibility allows it to hold its own in every situation, contextual changes notwithstanding.

Notes on the Contributor

Danica Anna D. Guban-Caisido is Assistant Professor and current Italian Section Coordinator of the Department of European Languages at the University of the Philippines Diliman. Her research interests include Foreign Language Teaching and Learning, Educational Psychology and Counseling, and Communication Studies.

References

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Carson, L., & Mynard, J. (2012). Introduction. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 3–25). Pearson.

Conley, D. (2020, November 20). Breadth vs. Depth: The deeper learning dilemma (opinion). Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/education/opinion-breadth-vs-depth-the-deeper-learning-dilemma/2015/10

Davies, H., Wongsarnpigoon, I., Watkins, S., Ambinintsoa, D. V., Terao, R., Stevenson, R., & Bennett, P. A. (2020). A self-access center’s response to COVID-19: Maintaining stability, connectivity, well-being, and development during a time of great change. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.37237/110304

Gao, L. X., & Zhang, L. J. (2020). Teacher learning in difficult times: Examining foreign language teachers’ cognitions about online teaching to tide over COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.549653

Guban-Caisido, D. A. D. (2020). Language advising as psychosocial intervention for first time self-access language learners in the time of COVID-19: Lessons from the Philippines. Sisal Journal, 148–163. https://doi.org/10.37237/110305

Hsieh, J. C., Marek, M. W., & Wu, W. V. (2022). Enhancing the quality of out-of-class learning in flipped learning. In H. Reinders, C. Lai, & P. Sundqvist (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language learning and teaching beyond the classroom (pp. 229–243). Routledge.

Hung, H. (2015). Flipping the classroom for English language learners to foster active learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2014.967701

Hurd, S. (2001). Managing and supporting language learners in open and distance learning environments. In Beyond language teaching towards language advising (pp. 135–148). CILT. http://oro.open.ac.uk/621/1/ManagSupporDLLs-Hurd-2001.pdf

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge.

Karlsson, L. (2012). Sharing stories: Autobiographical narratives in advising. In J. Mynard & L. Carlson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 185–204). Pearson.

Lage, M. J, Platt, G. J., & Treglia, M. (2000). Inverting the classroom: A gateway to creating an inclusive environment. The Journal of Economic Education, 31(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220480009596759

Lantolf, J. P., & Poehner, M. E. (2008). Introduction. In J. P. Lantolf & M. E. Poehner (Eds.), Sociocultural theory and the teaching of second languages (p. 1–32). Equinox.

MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., & Mercer, S. (2020). Language teachers’ coping strategies during the Covid-19 conversion to online teaching: Correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions. System, 94, 102352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102352

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. Jossey-Bass.

Moser, K. M., Wei, T., & Brenner, D. (2021). Remote teaching during COVID-19: Implications from a national survey of language educators. System, 97, 102431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102431

Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2012). The skills of counselling in advising: Language as a pedagogical tool. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools, context (pp. 43–64). Pearson.

Reinders, H. (2006). Supporting self-directed learning through an electronic learning environment. In T. Lamb & H. Reinders (Eds.), Supporting self-directed language learning (pp. 219–238). Peter Lang.

Ruiz-Guerrero, A. (2020). Our self-access experience in times of COVID. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 11(3), 250–263. https://doi.org/10.37237/110311

Spencer-Oatey, H. (2011). Conceptualising ‘the relational’ in pragmatics: Insights from metapragmatic emotion and (im) politeness comments. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(14), 3565–3578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2011.08.009

Subingsubing, K. (2022, July 11). UP shifts to blended learning. Inquirer News. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1625405/up-shifts-to-blended-learning

University of the Philippines (UP) (2020, March 17). On the suspension of classes in all UP constituent universities except UP Open University. https://up.edu.ph/memorandum-no-ovpaa-2020-38-on-suspension-of-classes-in-all-up-constituent-universities/

Ushioda, E. (2009). A person-in-context relational view of emergent motivation, self and identity. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp, 215–228). Multilingual Matters.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: Development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.