Thinley Wangdi,Saint Louis University, Baguio City, Philippines

Ringphami Shimray, Saint Louis University, Baguio City, Philippines

Wangdi, T., & Shimray, R. (2025). AI-powered ReadTheory as a self-access learning platform to enhance EFL learners’ reading enjoyment and comprehension skills: A posthumanist perspective Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(2), 437–460. https://doi.org/10.37237/160209

Abstract

The growing body of research on AI tools in ELT suggests that more studies are needed to fully realize the potential of AI tools, particularly as a self-access language learning (SALL) platform. This mixed-method study focused on how the use of ReadTheory, a web-based AI-powered tool, as a SALL platform, can enhance EFL learners’ reading enjoyment and comprehension skills. To this end, data were collected through pre-and post-surveys, as well as open-ended questions from 54 Thai EFL university students who willingly participated in a one-month SALL program. The analysis of quantitative data revealed that the use of ReadTheory as a SALL platform significantly enhanced learners’ reading enjoyment and comprehension skills. The thematic analysis of qualitative data discovered that participants viewed ReadTheory as a promising AI-powered SALL platform. They noted several benefits of ReadTheory, including its user-friendly interface, language skill development, adaptability, instant feedback, engaging experience, and ability to foster critical thinking. However, they also pointed out a few limitations of ReadTheory, such as limited explanations for incorrect answers, an over-reliance on multiple-choice questions, and minimal interactivity. This study concludes with some theoretical and practical implications of ReadTheory as a SALL platform.

Keywords: artificial intelligence, ReadTheory, self-access language learning, reading enjoyment, reading comprehension skills

Artificial intelligence (AI) has undoubtedly become a valuable tool in the field of English language teaching (ELT). There is evidence in the literature supporting the benefits of using AI tools for both ELT teachers and learners (Chea & Xiao, 2024; Rad et al., 2023; Wei, 2023). Among many AI tools, ReadTheory appears to have gained significant popularity in the field of ELT (Anqoudi et al., 2024). There are currently about 18 million users from 175 different countries. ReadTheory is a free, web-based platform that offers a wide range of reading materials (both fiction and non-fiction texts), exercises, and quizzes, along with instant feedback (see Appendix A) to help English learners enhance their reading and comprehension skills (Tempest, 2018). This AI-powered platform is especially recognized for its adaptive capabilities (Anqoudi et al., 2024). It adapts to students’ reading levels using AI, which analyzes their performance based on a randomly assigned pre-test with reading texts at A1 and A2 CEFR levels (see Appendix B), then providing tailored reading materials that become progressively more challenging and follow-up quizzes (Tempest, 2018). However, the text difficulty level of reading materials increases only if learners achieve a score of 90% or higher on the reading comprehension quizzes. If their scores are between 70% and 89%, the difficulty level remains the same, even though readers are assigned different texts. Similarly, when learners score 69% or lower, ReadTheory assigns different texts, but the difficulty level of reading materials decreases. ReadTheory also has a feature that monitors students’ real-time reading to prevent students from (quickly) guessing answers (students cannot simply click to move to the next session, see Appendix C). However, this feature lasts only for a short time, and students can randomly click on answers if they wish after a few seconds. The most notable feature of ReadTheory is that it simplifies teachers’ tasks by providing real-time monitoring of students’ reading progress and offering students immediate feedback (Anqoudi et al., 2024), thus helping them reduce their workload. It also helps teachers to monitor the progress of their students’ reading comprehension skills.

Despite the popularity of ReadTheory and its growing user base, which benefits both teachers and students, only a few studies (e.g., Anqoudi et al., 2024; Hidayat, 2024) have investigated its impact on English language learners’ reading comprehension skills, and these studies were conducted in classroom settings. There is a research gap regarding the effectiveness of ReadTheory, particularly as a SALL platform, in improving learners’ reading enjoyment and comprehension skills in the context of ELT, which makes this study unique. Thus, the findings of this study are expected to inform ELT educators about the potential use of ReadTheory as a SALL platform. To this end, the study first examines the impact of using ReadTheory as a SALL on Thai EFL learners’ reading enjoyment and comprehension skills. Second, it explores learners’ perceptions of ReadTheory as a SALL platform to gain deeper insights into its potential integration within the ELT field. The current study seeks to answer the following two research questions.

- To what extent does using ReadTheory as a SALL platform impact learners’ reading enjoyment and their self-perceived reading comprehension skills?

- How do Thai EFL students perceive the use of ReadTheory platform as a SALL platform?

Literature Review

Theoretical Framework of the Study

This study used posthumanism as a theoretical framework, which aims to blur the boundaries between humans and the technological world (Kriman, 2019). In other words, posthumanists believe that technology and human beings are inseparable and that they should be integrated towards the betterment of society. However, the term posthumanism is often misunderstood by many as being anti-human or something that goes beyond humanism. It is important to note that posthumanism does not indicate the absence of humans (Miah, 2008) and that it just focuses on rethinking the role of human beings within the ecological and technological frameworks (Kriman, 2019). The concept of posthumanism was deemed suitable for this study because Ulmer (2017) asserted that posthumanists aim to create a more just and equitable society by not only embracing views and opinions from individuals (human) of different races, genders, and sexual orientations but also by considering the aspects of those beyond human beings, such as technological world (AI in the case of this study). Since this study involves contributions from both human participants (teachers and students) and a non-human entity (ReadTheory) and aims to promote justice in education through evidence-based integration of AI tools amidst the dilemma among educators whether or not AI tools should be integrated into education, no theoretical framework other than posthumanism can effectively represent the essence of the research.

Studies on AI Tools in ELT

Research using mixed-methods approaches was conducted recently to explore the potential use of AI tools in the field of ELT. For instance, employing a mixed-method approach, Wei (2023) examined the impact of AI-assisted language instruction (Duolingo) on English language performance, L2 motivation, and self-regulated learning. The study involved 60 Chinese EFL university students. The study found that the use of Duolingo as an AI-driven instruction enhances learners’ academic achievement, motivation to learn a foreign language, and self-regulated learning. Similarly, Rad et al. (2023) examined the effectiveness of an AI-powered application commonly used for enhancing writing quality through summarization, paraphrasing, grammar and spelling checks called Wordtune on ESL learners’ writing performance. Their mixed-method study, which involved 46 Iranian upper intermediate students, highlighted that Wordtune could increase students’ writing performance, engagement, and ability to comprehend given feedback. In another mixed-method study, Chea and Xiao (2024) examined the effect of AI-assisted tools (Chatbot, Translation tools, Vocabulary checking) on academic English reading skills, with a focus on how they support Chinese students reading comprehension skills, vocabulary development, and critical thinking abilities. The findings suggested that integrating AI tools with traditional teaching methods such as lecture-based teaching, guided learning, and teacher-led discussion have a more significant positive impact on learners’ reading comprehension skills, vocabulary development, and critical thinking abilities. The authors concluded by recommending ELT educators consider incorporating AI into traditional teaching practices.

A few experimental and action research studies were also conducted to gain a deeper understanding of the effectiveness of AI educational tools. These include a study conducted by Ruan et al. (2021), which compared the performance of Chinese college students taught by using traditional methods with those who used EnglishBot, a conversational web-based application designed as a Chatbot to practice speaking English. They found that learners who engaged with EnglishBot were more motivated and demonstrated more fluency in speaking. Furthermore, Anqoudi et al.’s (2024) action research demonstrated that the use of AI-powered tools, such as ReadTheory, significantly improved Omani students’ reading comprehension skills. They also highlighted that ReadTheory contributed to increased engagement and motivation to read among their students. Similar findings reported in Hidayat’s (2024) experimental study conducted in Indonesia showed that ReadTheory helped their students perform better in post-reading comprehension tests.

Although the research studies above have found several useful AI tools for language learning (e.g., Duolingo, ChatGPT, Englishbot, translation tools, Wordtune, and ReadTheory) and subsequently investigated their effectiveness on different aspects of English language skills, not many have specifically explored the potential use of ReadTheory in ELT, particularly as a SALL platform, and its subsequent impact on EFL learners’ reading enjoyment and reading comprehension skills.

Self-Access Language Learning

Self-access language learning (SALL) has garnered significant interest from language educators within the field of ELT (Lai & Hamp-Lyons, 2001), as it supports learner autonomy by allowing students to choose their learning materials and work independently (Mynard, 2019). SALL helps learners take more control of their studies and gives them personalized support to meet their specific needs (Wangdi & Shimray, 2022). For this reason, self-access learning platforms, such as self-access language learning centers, often established to offer students an environment to meet the needs of learners and promote the growth of learner autonomy (Wangdi & Shimray, 2022), have become popular in the context of ELT.

Numerous research studies have shown the benefits of SALL on learners’ learning, learning experience, and language outcomes. For instance, Anggraeni et al. (2023) reported that SALL is often associated with learners’ improved writing skills because it encourages learners to learn beyond the four walls of the classroom. They also noted that students find SALL to be more engaging and effective than traditional classroom learning. Similarly, Wangdi and Shimray’s (2022) study conducted in Thailand suggested that using the Academic Word List as a self-access learning resource enhances EFL learners’ academic communication skills. Additionally, Mai (2023) highlighted that Vietnamese students hold positive perceptions of using online self-access listening platforms, pointing to the potential of online SALL as an effective platform in the digital era. The benefits of online SALL were also highlighted by Kelly et al.’s (2020) study, which was conducted to support Australian university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the potential of SALL platforms in both classroom and online settings has been widely explored in the literature, there is a notable gap in research regarding the use of AI-powered tools as a SALL platform. This gap underscores the importance of conducting this study.

Reading Enjoyment and Reading Comprehension Skills

Better reading comprehension skills are often linked to better listening, speaking, and writing abilities and academic performance (Smith et al., 2021; Wangdi & Rai, 2024). Reading comprehension, often believed to be enhanced by learners’ reading enjoyment (Rogiers et al., 2020), is considered one of the most important skills in foreign language learning (Wangdi & Rai, 2024). Guthrie and Klauda (2014) define reading enjoyment as a sense of happiness felt by readers while reading texts. Several studies have been conducted to make reading more enjoyable for ELT learners because research has shown a positive relationship between learners’ reading enjoyment and reading comprehension skills (Rogiers et al., 2020). Some commonly highlighted strategies incorporated by ELT educators to enhance their learners’ reading enjoyment levels in the literature include selecting reading materials based on learners’ interests and the use of authentic materials (Whitten et al., 2019). Furthermore, Sheridan and Condon (2020) pointed out that integrating reading text that reflects learners’ own culture and giving easier topics can enhance EFL learners’ reading enjoyment. Korkmaz and Öz (2021) and Erya and Pustika (2021) suggested that implementing gamified learning apps like Kahoot and Webtoon respectively can stimulate and contribute to a more enjoyable reading experience among learners. In conclusion, while previous researchers have highlighted the importance of reading enjoyment and comprehension skills and have explored various strategies to enhance them, there is a gap in knowledge examining the role of ReadTheory in improving learners’ reading enjoyment and comprehension skills.

Method

Research Design

This study employed a mixed method research design (Creswell et al., 2003) to investigate the potential use of ReadTheory as a SALL platform in the field of ELT. The mixed method was used because it is often regarded as a rigorous method that provides a deeper understanding of the phenomenon under investigation (McKim, 2017). The quantitative data was collected using a pre-test and post-test quasi-experimental research design. It examined the impact of ReadTheory as a SALL platform on learners’ reading enjoyment and self-perceived reading comprehension skills. The quasi-experimental method was chosen for this study because researchers had limited control over the true randomization of participants (see Rogers & Revesz, 2019) due to the pre-existing group assigned by the institution. The qualitative data involved participants’ responses to three open-ended questions. It explored their perceptions of the potential use of ReadTheory as a SALL platform.

Participants

The population of this study was 54 (26 males, 26 females, and 2 nonbinary) Thai EFL first-year undergraduate students, aged 18 to 23 years. At the time of the research, these students were enrolled in the same class and taking a General English course, English reading and writing, taught by the teacher-researcher, who is the second author. They were majoring in Business Administration, Environmental Engineering, and Management. To respect confidentiality, students are referred to as Student 1 to Student 29 throughout the paper.

Instruments

The instruments included pre-and post-surveys, self-perceived reading comprehension skills (SPRCS) scale, and open-ended questions. All these questions were provided bilingually (in Thai and English), with students having options to respond, particularly to open-ended questions in both Thai and English, to obtain more detailed and comprehensive responses.

Survey and Self-Perceived Reading Comprehension Skills Scale (SPRCS)

The survey questionnaire was adapted from Cai et al. (2024) (see Appendix D). The survey consisted of demographic questions (e.g., age, gender, student ID, and SPRCS) and five five-point Likert Scale questionnaires (strongly disagree = 1, strongly agree = 5). It measured participants’ reading enjoyment (e.g., reading is one of my favorite hobbies) levels before and after the intervention. As for SPRCS, we developed a survey instrument based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) reading levels (see Appendix E). It aimed to examine learners’ self-perceived reading comprehension skills before and after the intervention. It consisted of six levels (A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, and C2) and participants were asked to report their SPRCS (e.g., A1– “I can understand familiar names, words and very simple sentences, for example on notices and posters or in catalogues”).

Open-Ended Questions

Researchers devised three open-ended questions (see Appendix F) that explored learners’ perceptions about the potential use of ReadTheory as a SALL platform. To ensure that the questions measure the intended research objective, the questions were verified and validated by two qualitative research experts, and a pilot test was done with two random students before employing them in this study.

Data Collection Procedure

The second author gathered the data in the academic year 2024. Before data collection, ethical considerations were thoroughly addressed by obtaining consent from both the head of the department and the participants. Further, participants were verbally informed in the classroom by the second author that the data collected through surveys and open-ended questions would be used solely for research purposes and would have no impact on their academic grades. They were also assured that all information would be treated with the utmost confidentiality, and their identities would not be disclosed in any published findings. Additionally, participants were informed that they could opt out or withdraw from the study at any time, should they feel uncomfortable. Following a concise introduction to the research objectives, the second author conducted a pre-survey before the intervention. A post-survey was conducted following the one-month intervention. Furthermore, students who completed 10 or more readings were asked to respond to the three open-ended questions after the intervention.

Intervention

At the beginning of the semester, the teacher (the second author) introduced students to ReadTheory and explained in the classroom how to use it. During the same session, students were asked to register for ReadTheory. After assisting students with registration, the teacher shared his classroom code and asked all students to join so he could monitor their progress and the number of reading materials completed by each student. Students were told that they were able to take the ReadTheory pre-test and complete the assigned reading materials and quizzes at their convenience. They were also orally informed and strongly encouraged to complete at least 10 reading materials including texts and quizzes on ReadTheory with a score of at least 75% over a month, irrespective of the difficulty level of the texts. These criteria of completing a minimum of 10 reading texts with a score of at least 75% were set in this study to ensure that students take reading comprehension quizzes seriously and to discourage them from randomly selecting answers while completing reading comprehension tasks.

Experimental and Comparison Group Criteria

In this study, students who completed at least 10 reading texts with a score of 75% or higher were placed in the experimental group, whereas those who did not were placed in the control group. More specifically, out of 54 students, 29 were placed in the experimental group as they met the criteria, while the remaining 25 students, who completed nine or fewer reading materials with a score above 75%, were assigned to the comparison group. It should be noted that the majority of students had completed more than 10 reading texts, but some of their tasks were not considered completed due to the 75% and above score inclusion criteria. For instance, although 43 out of 54 students completed 10 or more reading texts and quizzes, only 29 of them scored 75% or higher on at least 10 reading materials. Thus, 14 out of 43 students were excluded and placed in the comparison group despite completing 10 reading texts. Of the remaining 11 students, four had completed three readings with scores below 75%, one student completed only two readings with scores below 75%, and six students did not complete any reading tasks.

Data Analysis

To address the first research question, descriptive analyses such as mean and standard deviation were calculated, and the normality of the data was tested using SPSS. After confirming the normality of the data with Z values between +2 and -2 for both skewness and kurtosis, a paired sample t-test (95% confidence level) was used to assess the mean difference in learners’ enjoyment of reading and SPRCS before and after the intervention. To answer the second research question, data from open-ended questions were thematically analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) guidelines, which included data familiarization, initial coding, searching themes, reviewing themes, defining and identifying themes, and reporting. During the initial phase, which involved familiarization with the data, researchers transcribed and read the participants’ responses to open-ended questions. The transcribed data was then sent to participants who responded to open-ended questions for member checking. This helped improve the credibility and accuracy of the transcribed data (see Shimray & Wangdi, 2023). Next, researchers conducted the initial coding. At this stage, we independently conducted the initial coding to later compare their results and establish inter-coder reliability (ICR), thereby enhancing the credibility of the findings (MacPhail et al., 2016). Codes such as ReadTheory is easy to use and ReadTheory is adaptive were crafted by reading and re-reading transcriptions many times. After establishing ICR through Cohen’s Kappa Coefficient (0.85), researchers searched for potential themes, reviewed, defined and named themes. This step gave researchers nine sub-themes such as user-friendly interface and adaptive, constructed by constantly reviewing generated codes and transcriptions. These sub-themes were then categorized into two larger categories or main themes: ReadTheory: Potential SALL platform and limitations of ReadTheory. Finally, before reporting the findings, the entire process of data analysis was audit trialed (Creswell & Miller, 2000) by a qualified researcher to establish the trustworthiness and credibility of the findings.

Results

Quantitative Findings

The quantitative results on the effect of ReadTheory as a SALL platform on participants’ reading enjoyment levels and their SPRCS revealed that students who completed 10 or more reading materials from ReadTheory had a significant increase in their reading enjoyment levels and SPRCS after a month of intervention when compared to their pre-intervention reading enjoyment levels and SPRCS. The paired sample t-test comparison of pre-and post-surveys for both experimental and comparison groups are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1

Pre- and Post-Reading Enjoyment Levels (N = 54)

The result illustrated in Table 1 revealed a significant difference (P < 0.01) between students’ pre- and post-reading enjoyment levels. The average mean value of the pre-intervention reading enjoyment level was 2.823 (SD = .428), which is significantly lower than post-intervention (M = 3.689, SD = .529), with an average mean difference of 0.866. To determine whether the intervention had a genuine impact on participants’ reading enjoyment levels, the pre-and post-data of the comparison group were also analyzed. The results indicated that no significant difference was found in their reading enjoyment before (M = 3.230, SD = 0.509) and after (M = 3.470, SD = 0.612), as shown by the average mean values. Overall, the findings on the increased reading enjoyment levels after the intervention suggest that ReadTheory has the potential to be used as a SALL platform to enhance learners’ reading enjoyment.

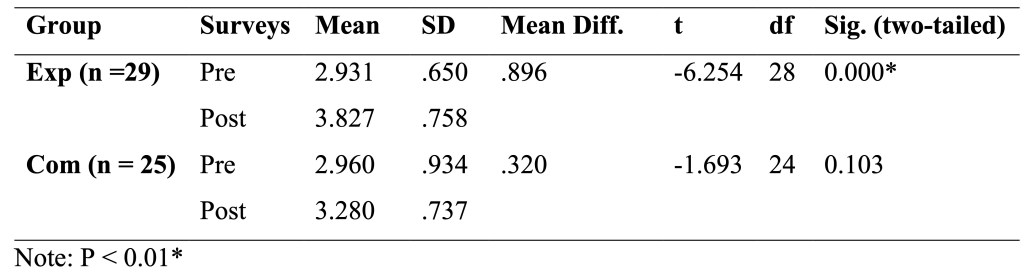

Table 2

Pre- and Post SPRCS (N =54)

As indicated in Table 2, the average mean value (M = 3.827, SD = 0.650) of SPRCS after the intervention was significantly higher than that of the pre-intervention mean value (M = 2.931, SD = 0.758), suggesting that ReadTheory has a potential to be used as SALL platform to enhance learners’ reading comprehension skills. The effectiveness of the intervention was further validated by the non-significant difference in the average mean values of the comparison group after one month. For the comparison group, the mean difference before and after one month remained nearly the same, with a mean difference of only 0.320.

Qualitative Findings

The qualitative findings are presented under two main themes: ReadTheory: Potential SALL platform and limitations of ReadTheory as a SALL platform. These two major themes encompassed nine sub-themes derived from the generated codes. The number of students referencing the same codes is indicated in parentheses. It is important to note that the total number of students indicated in parentheses sometimes exceeds 29 (the total sample who completed open-ended questions) because some students reported multiple codes/aspects (e.g., both benefits and limitations) in a single response. For instance, one student mentioned that ReadTheory is beneficial because it is adaptive and easy to use.

ReadTheory: Potential SALL Platform

The first qualitative finding revealed that learners view ReadTheory as a potential SALL platform for several reasons. Within the main theme of ReadTheory: Potential SALL platform, six sub-themes were identified such as user-friendly interface (15 students), enhances learners’ language skills (11 students), adaptive (9 students), offers instant feedback (7 students), engaging (7 students), and fosters learners’ critical thinking ability (5 students). The majority of the participants mentioned that ReadTheory is easy to use. For instance, Student 15 said, “I think ReadTheory platform helped me use some of my free time to read some interesting stories. The website is easy to use and we can use it from anywhere.” The second reason why learners found that ReadTheory has the potential to be used as SALL was their perceived benefits of improving their language skills. ReadTheory not only helped learners improve their reading comprehension skills, but also improved other fundamental elements of language such as vocabulary, grammar, and writing. For instance, Student 27 said, “In my opinion, ReadTheory helped me improve my reading skills, vocabulary, and grammar. It has many interesting stories and it is not boring.” Further, Student 5 contended, “ReadTheory helped me improve both my reading and writing skills. My two weaknesses.”

It appears that learners were impressed with the adaptive nature of ReadTheory and its ability to support personalized learning. Student 4 mentioned that “ReadTheory is adaptive and it can be used for students with various reading levels.” Another benefit noted was inbuilt instant feedback support from ReadTheory. For instance, Student 22 said, “What I like most about ReadTheory is the immediate feedback it provides when we answer quizzes wrong. This kept me engaged and helped me fully understand the stories.” Similarly, participants mentioned that ReadTheory is enjoyable and engaging. For example, Student 11 asserted that “ReadTheory is very fun. It helped me improve my reading skills. Normally, I do not read English books and stories. But after the teacher introduced me to ReadTheory I found myself enjoying reading some entertaining stories on ReadTheory.” Lastly, five students mentioned that ReadTheory is a useful AI-driven reading platform to improve their critical thinking ability. For example, Student 7 stated, “ReadTheory is especially effective for students because it helps promote critical thinking by making students answer difficult questions and read many stories. But its effectiveness depends on how consistent are students.”

Limitations of ReadTheory

Although the majority of participants reported ReadTheory as a potential tool to be used as a SALL platform for EFL learners, some expressed their reservations. They pointed out that ReadTheory lacks in some instances. Under the main extracted themes of limitations of ReadTheory, three sub-themes such as limited feedback on incorrect answers (13 students), excessively reliance on multiple-choice questions (MCQs) (8 students), and limited interaction (8 students) were discovered. Many participants who reported drawbacks of ReadTheory felt that it lacked an in-depth explanation for incorrect answers. For instance, Student 6 commented, “ReadTheory lacks in-depth explanations of our response. Sometimes, I felt like I needed more clarification to fully understand my mistakes.” Additionally, participants in this study noted that ReadTheory’s heavy reliance on MCQs occasionally triggered their boredom. It seems that students desire a variety of question types, such as open-ended questions and gap-filling exercises. Student 24 said, “ReadTheory lacks variation in question types. It primarily focuses on multiple-choice questions. This hindered my deeper comprehension of the text as it does not address nuanced or open-ended aspects of reading materials.” Another notable limitation of ReadTheory perceived by the participants was its lack of interactive capabilities. Student 2 mentioned that “the interaction is too limited, as there is no interactive teaching or further explanation like humans. So, it is not possible to find detailed answers to questions that are not understood.”

Discussion

The current study adopted posthumanism as its theoretical framework to explore how recent technological advancements such as ReadTheory can assist humans (learners) beyond classroom settings to enhance and transform the learning experiences and performance of ELT learners. To this end, the study investigated the potential of ReadTheory as a SALL platform in the ELT field by investigating its impact on learners’ reading enjoyment, comprehension skills, and their perceptions of its use as a SALL platform. The general findings suggested that the use of ReadTheory as a SALL platform can help English language learners improve their reading enjoyment and comprehension skills, provided ELT educators consider some limitations of ReadTheory provided in this paper.

Relationship between ReadTheory and Learners’ Reading Enjoyment and Comprehension Skills

This study found that the use of ReadTheory can significantly enhance learners’ reading enjoyment. This finding partially aligns with other research investigating the impact of technological tools, including ReadTheory in enhancing reading enjoyment (e.g., Anqoudi et al., 2024; Erya & Pustika, 2021; Korkmaz & Öz, 2021; Ruan et al., 2021). The alignment was only partial because previous studies did not investigate the impact of technological (including AI) tools through the lens of the SALL platform. They subtly suggested that utilizing modern technological tools like Kahoot, Chatbots, Webtoons, and ReadTheory increases learners’ reading enjoyment, while also boosting their interest and motivation to continue reading.

The increased reading enjoyment observed among participants in this study is likely linked to the engaging content available on ReadTheory, particularly the stories. Some participants mentioned their interests in the stories, which helped them enhance their reading enjoyment. The assumption that content such as stories could have assisted learners improve their reading enjoyment aligns with the theory of imaginative education (Egan & Judson, 2016), which highlights that cognitive classroom tools, such as stories, humor, and metaphors, aid learners connect their prior knowledge with their emotions (enjoyment, in the case of this study). Another reason for enhanced reading enjoyment after adopting ReadTheory as a SALL platform could be the learners’ perceived adaptive nature of ReadTheory. As noted earlier and also by the participants in their responses to open-ended questions, ReadTheory assigns reading materials to learners based on their reading abilities determined by pre-test scores. This feature of ReadTheory may have ensured that the materials were neither too difficult nor too easy, thus reducing learners’ boredom (Shimray & Wangdi, 2023). Overall, this study suggests that ReadTheory has the potential to serve as an effective SALL platform for enhancing EFL learners’ reading enjoyment.

The study also found that ReadTheory, as a SALL platform, has the potential to increase learners’ reading comprehension skills. The positive impact of ReadTheory on learners’ reading comprehension skills, as measured by their self-perceived reading comprehension skills, is however not surprising given that ReadTheory was purposely developed/designed to help learners improve their reading skills (see Tempest, 2018). Nonetheless, the findings on the positive impact on learners’ reading comprehension skills contribute to earlier studies on ReadTheory with similar findings (Anqoudi et al., 2024; Hidayat, 2024) but offer a unique perspective by focusing on SALL. The reason for the positive influence on reading comprehension skills in this study could be attributed to learners’ increased reading enjoyment, which is in line with other studies showing a positive correlation between learners’ reading enjoyment and their reading comprehension skills (e.g., Rogiers et al., 2020).

ReadTheory as a SALL Platform

The overall findings on the potential use of ReadTheory as a SALL platform suggest that it is a double-edged AI-powered tool, encompassing both benefits and limitations, consistent with the broader features described in other studies (Anqoudi et al., 2024; Hidayat, 2024). Another interesting finding uncovered in this study was learners’ perceived benefits of using ReadTheory on their other linguistics components such as vocabulary knowledge, grammar knowledge, and writing skills in addition to the development of their reading comprehension skills. This benefit may have arisen from the fact that most of the materials on ReadTheory consist of stories. Hişmanoğlu (2005) highlighted that when students read stories, it helps them improve their knowledge of other components of language such as vocabulary and grammar. This finding suggests that ReadTheory has several benefits other than improving reading comprehension skills if it is integrated into teaching the English language. Furthermore, the participants mentioned that ReadTheory helped enhance their critical thinking abilities, likely due to the stories they read on the platform. In this context, Shazu (2014) underscored that reading literary works, such as stories helps learners boost their critical thinking, as students often engage in analyzing the elements of stories, such as characters, settings, plots, conflicts, and morals.

However, it should be noted that participants also pointed out some limitations of using ReadTheory as a SALL platform. They particularly mentioned three limitations: ReadTheory lacks a detailed explanation of incorrect answers, is overly dependent on MCQs, and has limited interaction. This adds to existing research studies on ReadTheory (Anqoudi et al., 2024; Hidayat, 2024; Tempest, 2018), which did not highlight the limitations of ReadTheory. Regarding the first limitation of ReadTheory, although our earlier findings showed that some participants appreciated the immediate/quick feedback, it appears that others found it inadequate, as they mentioned that ReadTheory lacks in-depth explanations for their incorrect answers (see Appendix A). The second limitation of ReadTheory pertains to its overreliance on MCQs, which, according to participants, hindered their deeper understanding of the reading texts. Finally, participants reported being deprived of interaction while using ReadTheory. The reason students felt deprived of interaction may stem from inadequate explanations of incorrect answers. They likely wanted to seek clarification or address doubts that arose while completing the reading exercises. This finding supports the posthumanist belief, which recognizes the importance of blurring boundaries between human and non-human entities such as technology (Kriman, 2019), suggesting that the use of ReadTheory in isolation or without human involvement may have negative repercussions on students’ learning. On the whole, although AI tools such as ReadTheory may help revolutionize the way the English language is being taught, their effectiveness in enhancing learners’ experiences and emotions is likely to be limited without human intervention.

Implications

Although much has been written about the potential use of AI-powered tools in the ELT field, including ReadTheory, this study differs from previous studies because it specifically focused on the potential use of ReadTheory as a SALL platform. Therefore, the insights gained from this study have meaningful theoretical and practical significance, particularly for ELT in education. From a theoretical standpoint, this study aligns with the philosophical movement of posthumanism, which asserts that humans should not be viewed as the sole agents of knowledge. Thus, ELT educators are suggested to explore advancements in technology, especially AI-powered tools, and integrate them beyond traditional classroom settings to enhance learners’ learning experiences, progress, and language achievements. The findings of this study support this suggestion, showing that AI-powered tools like ReadTheory when used as a SALL platform, can enhance learners’ reading enjoyment and comprehension abilities. Besides, the use of ReadTheory outside the classroom also helped learners enhance their linguistics skills, learning experience, and critical thinking ability. All of these suggest that ReadTheory could serve as a valuable SALL platform.

As for practical implications, the findings of this study are likely to be valuable for ELT policymakers, teachers, students, and researchers. ELT policymakers would benefit from this study as it offers insight into how educators can leverage recent technological advancements, such as artificial intelligence, to transform the language learning environment beyond the four walls of the classroom. Policymakers can accordingly work on encouraging teachers to integrate AI-powered tools by providing frequent workshops, training sessions, and newsletters on recent developments in AI-powered educational tools. Likewise, ELT teachers may benefit from this study as it provides them with a valuable, empirically validated AI-powered tool that can be used as a SALL platform to enhance students’ reading enjoyment and comprehension skills. ELT teachers should note, however, that there is a potential drawback of using ReadTheory as a SALL platform in isolation, as it is not without limitations. Therefore, to achieve the best outcome, ELT teachers are advised to use ReadTheory as a SALL platform either as an extension of their classroom activities or by monitoring it closely. Moreover, since this study highlights both the potential drawbacks and benefits of using ReadTheory as a SALL platform, L2 learners who wish to improve their reading comprehension, along with other fundamental language components such as vocabulary and grammar, at their own pace, without the need for human teachers, may benefit from this study. Finally, this study may inspire future ELT researchers to delve deeper into the use of AI-powered tools as a SALL platform in L2 education, especially through the lens of the posthumanism movement. Additionally, future researchers can focus on addressing the limitations identified in this study.

Limitations and Conclusions

Although this study offers an interesting insight into the potential use of ReadTheory as a SALL platform, we acknowledge some limitations that future researchers may wish to address. The primary limitation lies in the relatively small sample size. Future researchers should consider conducting a similar study but with a larger sample size to corroborate the current findings. Another limitation pertains to the criteria set for categorizing the participants into experimental and comparison groups. It is possible that the students in the experimental group who completed 10 reading tasks with scores of at least 75% had higher reading enjoyment and comprehension skills even before the research, which may have affected our quantitative findings regarding the effectiveness of ReadTheory in enhancing learners’ reading enjoyment and comprehension skills. Therefore, similar studies but without a score restriction should be done to confirm the current findings. Furthermore, we collected data using self-reported instruments only. Such data is often criticized for its potential response biases (Shimray & Wangdi, 2023) and inaccuracies (Gonyea, 2005). Thus, the findings presented in this study may not be a generalizable reflection of the effectiveness of ReadTheory, particularly regarding reading enjoyment levels and reading comprehension skills. Additionally, a one-month intervention may not be enough to gauge the true effect of any intervention. A longitudinal study may provide deeper insights into the effectiveness of ReadTheory as a SALL platform in L2 education. Finally, if we had also surveyed the students who completed less than 10 reading tasks, we might have found more disadvantages of ReadTheory. This could be an interesting gap for future research.

Nonetheless, this study concludes that ReadTheory can be used as a SALL platform in ELT, as its use has the potential to enhance learners’ reading enjoyment, comprehension skills, and other components of the English language (e.g., vocabulary and grammar). While this study recommends ELT educators use ReadTheory as a SALL platform, its limitations presented in this study should not be overlooked. In other words, ELT educators are encouraged to evaluate AI-powered educational tools through classroom action research and pilot studies to ensure their effectiveness and suitability before implementing them as SALL platforms.

Notes on the Contributors

Thinley Wangdi is a PhD student at Saint Louis University. He works as a lecturer at SOLGEN, Walailak University. His research interests include educational psychology, teacher education, and areas related to ELT. His recent publications appear in reputed journals such as South Asia Research, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, E-learning and Digital Media, and TESL-EJ.

Ringphami Shimray is a PhD student at Saint Louis University. He works as a lecturer at Prince of Songkla University International College, Hatyai Campus. His research interests include English language teaching, educational technology, and teacher education.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to Dr. Geraldine Siagto-Wakat, School of Humanities, Saint Louis University, Baguio City, Philippines, for her continuous support throughout the course of this study. The authors would also like to extend their gratitude to Assist. Prof. Dr. Mark Bedoya Ulla and Assist. Prof. Dr. Marlon Domagco Sipe, both from the School of Languages and General Education, Walailak University, Thailand, for reviewing our manuscript and providing valuable feedback.

References

Anqoudi, S. al, Gabarre, C., Gabarre, S., & Aamri, S. A. (2024). Improving EFL learners’ reading motivation with intensive reading using “ReadTheory”. International Journal of Linguistics, 15(5), 30–50. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v15i5.21389

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1191/1478088706QP063OA

Cai, Y., Peng, X., & Ge, Q. (2024). The tango between perceived cognitive load and enjoyment of reading in determining reading achievement. Reading and Writing, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-024-10580-1

Chea, P., & Xiao, Y. (2024). Artificial intelligence in higher education: The power and damage of AI-assisted tools on academic English reading skills. Journal of General Education and Humanities, 3(3), 287–306. https://doi.org/10.58421/gehu.v3i3.242

Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Into Practice, 39(3), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

Creswell, J. W., Clark, V. L. P., Gutmann, M. L., & Hanson, W. E. (2003). Advanced mixed methods. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (pp. 209–240). SAGE Publications. http://rszarf.ips.uw.edu.pl/ewalps/teksty/creswell.pdf

Egan, K., & Judson, G. (2016). Imagination and the engaged learner: Cognitive tools for the classroom. Teachers College Press.

Erya, W. I., & Pustika, R. (2021). Students’ perception towards the use of webtoon to improve reading comprehension skills. Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning, 2(1), 51–56. https://doi.org/10.33365/jeltl.v2i1.762

Gonyea, R. M. (2005). Self‐reported data in institutional research: Review and recommendations. New directions for institutional research, 2005(127), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.156

Guthrie, J. T., & Klauda, S. L. (2014). Effects of classroom practices on reading comprehension, engagement, and motivations for adolescents. Reading Research Quarterly, 49(4), 387–416. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.81

Hidayat, M. T. (2024). Effectiveness of AI-Based personalised reading platforms in enhancing reading comprehension. Journal of Learning for Development, 11(1), 115–125. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1423545.pdf

Hişmanoğlu, M. (2005). Teaching English through literature. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 1(1), 53–66. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jlls/issue/9921/122816

Kelly, A., Johnston, N., & Matthews, S. (2020). Online self-access learning support during the COVID-19 pandemic: An Australian university case study. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 11(3), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.37237/110307

Korkmaz, S., & Öz, H. (2021). Using Kahoot to improve reading comprehension of English as a foreign language learners. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching, 8(2), 1138–1150. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1294319.pdf

Kriman, A. I. (2019). The idea of the posthuman: A comparative analysis of transhumanism and posthumanism. Russian Journal of Philosophical Sciences, 62(4), 132–147. https://www.phisci.info/jour/article/view/2592/2438

Lai, L., & Hamp-Lyons, L. (2001). Different learning patterns in self-access. RELC Journal, 32, 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688201032002

MacPhail, C., Khoza, N., Abler, L., & Ranganathan, M. (2016). Process guidelines for establishing intercoder reliability in qualitative studies. Qualitative research, 16(2), 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794115577012

Mai, V. L. T. (2023). Autonomy-based listening: Vietnamese university students’ perceptions of self-access web-based listening practices. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(3), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.37237/140303

McKim, C. A. (2017). The value of mixed methods research: A mixed methods study. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 11(2), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689815607096

Miah, A. (2008) A critical history of posthumanism. In Gordijn, B. & Chadwick, R. (Eds.), Medical Enhancement and Posthumanity. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8852-0_6

Mynard, J. (2019). Perspectives on self-access in Japan: Are we simply catching up with the rest of the world? Mélanges CRAPEL, 40, 14–27.

Rad, H. S., Alipour, R., & Jafarpour, A. (2023). Using artificial intelligence to foster students’ writing feedback literacy, engagement, and outcome: A case of Wordtune application. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(9), 5020–5040. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2208170

Rogers, J., & Revesz, A. (2019). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs. In The Routledge handbook of research methods in applied linguistics (pp. 133–143). Routledge.

Rogiers, A., Van Keer, H., & Merchie, E. (2020). The profile of the skilled reader: An investigation into the role of reading enjoyment and student characteristics. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101512

Ruan, S., Jiang, L., Xu, Q., Liu, Z., Davis, G. M., Brunskill, E., & Landay, J. A. (2021). Englishbot: An AI-powered conversational system for second language learning. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces (pp. 434–444). https://doi.org/10.1145/3397481.3450648

Shazu, R. I. (2014). Use of literature in language teaching and learning: A critical assessment. Journal of Education and Practice, 5(7), 29–35 https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234635459.pdf

Sheridan, R., & Condon, B. (2020). Letting students choose: How culture influences text selection in EFL reading courses. Journal of Asia TEFL, 17(2), 523–539. http://dx.doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2020.17.2.14.523

Shimray, R., & Wangdi, T. (2023). Boredom in online foreign language classrooms: Antecedents and solutions from students’ perspective. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2178442

Smith, R., Snow, P., Serry, T., & Hammond, L. (2021). The role of background knowledge in reading comprehension: A critical review. Reading Psychology, 42(3), 214–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2021.1888348

Tempest, C. (2018). Implementation of ReadTheory in a university EFL context. OnCue Journal, 11(1), 81–91. http://jaltcue.org/files/OnCUE/OCJ11.1/OCJ11.1_pp81-91_Tempest.pdf

Ulmer, J. B. (2017). Posthumanism as research methodology: Inquiry in the anthropocene. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(9), 832–848. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2017.1336806

Wangdi, T., & Rai, A. (2024). Enhancing reading comprehension skills among Bhutanese English learners through translanguaging. Studies in English Language and Education, 11(3), 1473–1492. https://jurnal.usk.ac.id/SiELE/article/view/37882

Wangdi, T., & Shimray, R. (2022). Investigating the significance of Coxhead’s academic word list for self-access learners. SiSal Journal, 13(3), 367–388. https://doi.org/10.37237/130305

Wei, L. (2023). Artificial intelligence in language instruction: impact on English learning achievement, L2 motivation, and self-regulated learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1261955

Whitten, C., Labby, S., & Sullivan, S. L. (2019). The impact of pleasure reading on academic success. The Journal of Multidisciplinary Graduate Research, 2(1), 48–64. https://jmgr-ojs-shsu.tdl.org/jmgr/article/view/11/10

Appendices

See PDF version