Haruka Ubukata, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan. https://orcid.org/0009-0005-1902-1586

Emily Marzin, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2737-4945

Isra Wongsarnpigoon, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan. https://orcid.org/0009-0003-0164-887X

Ubukata, H., Marzin, E., & Wongsarnpigoon, I. (2025). Student perspectives on in-house self-access materials at a Japanese university. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(2), 391–417. https://doi.org/10.37237/160207

Abstract

Many language learners benefit from a wide range of resources provided by self-access learning centers (SALCs), environments specifically designed to facilitate autonomous language learning. For professionally published materials, various criteria have been proposed to select and evaluate resources for inclusion in SALCs. However, few sets of criteria exist that focus on materials designed in-house at particular institutions to meet learners’ needs. This study represents an initial attempt to begin filling this gap by investigating learners’ perspectives on in-house materials in a SALC at a private university in Japan. Nine learners, who were student staff at the SALC, participated in guided group discussions. They described their experiences with the in-house materials in the SALC and their impressions of the materials upon hands-on inspection. These discussions were coded based on a checklist for evaluating SALC materials developed by Reinders and Lewis (2006) and Yamaguchi et al. (2019), and in the process of analysis, new categories were added where necessary. The results suggested that supporting SALC users in their learning process is perceived as an important aspect of in-house materials by the learners and that visual design seems to carry great importance to Japanese university students in the context studied.

Keywords: self-directed learning, self-access learning center, material development, design, evaluation

Recent years, particularly in the post-Covid and digital age, have seen a shift in conceptualizations of self-access learning. Whereas self-access learning centers (SALCs) might have once heavily emphasized the provision of materials and resources for learners 20 or 30 years ago, many current SALCs have evolved to focus on inclusive, social learning in complex ecosystems (for more on this evolution, see Everhard, 2022; Gardner & Miller, 2021; Mynard, 2024; Mynard et al., 2022; Thornton, 2024). In the conventional sense, SALCs have traditionally provided various learning resources to support language learners. Rather than relying solely on externally sourced and published materials such as books or movies, they have also been able to complement these resources and further meet users’ specific needs through in-house materials. Developed by the facility faculty, these materials guide SALC users in making autonomous decisions regarding their self-directed language learning process and can include materials such as self-diagnostic worksheets or lists of recommended resources. Even amid the current reconceptualization of self-access learning, such materials are still relevant. For instance, they can help learners to effectively use available spaces and resources, in turn taking ownership of the spaces, or they can scaffold users in making better-informed selections from the vast multitude of potential resources available online in the digital age. Furthermore, they can foster reflection on the learning process, which is often part of SALCs’ goals of promoting learner autonomy. However, effectively developing such materials requires exploration of SALC users’ expectations for and potential usage of those resources.

This article explores student staff’s perspectives on a selection of in-house materials in a SALC at a Japanese university. After an examination of current literature on self-access materials, the research methodology is introduced, along with the rationale for conducting group discussions with the student staff. The results of the discussions follow, including aspects of materials that were found to require attention and ideas that were suggested in order to improve the materials. Finally, the study’s limitations are addressed, and several practical recommendations for SALC practitioners are introduced.

Resources in Self-Access Learning Centers

SALCs play an important role in supporting language learners’ development (Edlin & Imamura, 2018). These facilities (of varying size and focus of support) acknowledge individual differences and provide access to various resources (e.g., spaces, human resources, physical materials) according to individuals’ needs and interests (Gardner & Miller, 1999). The following section reviews the types of materials commonly offered in SALCs.

Materials in SALCs

To meet learners’ various interests, needs, and wants, SALCs provide a range of materials such as books for pleasure reading, textbooks for improving language skills, DVDs, or magazines. They tend to include published language learning materials, which may be authentic or pedagogical, and in-house ones, which are designed by faculty to fit the specific learners’ needs in each setting (Gardner & Miller, 1999). These materials are organized into sections for easy access. For example, a SALC may have a Reading section for materials for pleasure reading (e.g., novels, magazines) and an Academic Reading Section (e.g., reading-skill-based materials; Edlin & Imamura, 2018). Materials for activities such as board games may also be made available to promote learners’ target language use (Domínguez-Gaona et al., 2012).

It should be noted that the purpose of materials in SALCs tends to differ from those in libraries or traditional language labs. Although those facilities may superficially seem similar in that they also provide numerous materials, SALCs obtain materials to support learners’ learning process, rather than solely providing information (Reinders, 2012). Additionally, SALC materials need to be usable independently, as learners often have little direct support from a teacher in self-access learning settings (Reinders & Lewis, 2005). Fulfilling these goals, along with accommodating the needs and interests of learners at different levels of target language proficiency and with varying degrees of capacity for self-directed learning, are often challenging tasks for SALC practitioners.

One way to address this challenge is the production of bespoke materials. These can include, for instance, worksheets containing original grammar practice exercises accompanied by answer keys (Domínguez-Gaona et al., 2012; Rowberry, 2004) or listening activities to be used with specific authentic materials (Kershaw et al., 2010). These in-house materials, typically created by faculty or staff for learners in a particular learning environment, comprise an important part of a SALC’s material selection. Among their advantages are their abilities to cater to the different needs, interests, and levels of SALC users; be used specifically for self-access; and provide guidance concerning other materials available in the SALC (Kershaw et al., 2010). Especially when commercial materials are subject to publishers’ constraints (e.g., page numbers, contents, design; Sinclair, 1996), in-house materials are necessary to supplement other resources (Rowberry, 2004). Studies focusing on in-house materials within self-access environments remain relatively limited, indicating a need for further investigation in a variety of educational and cultural contexts.

Evaluation of SALC Materials

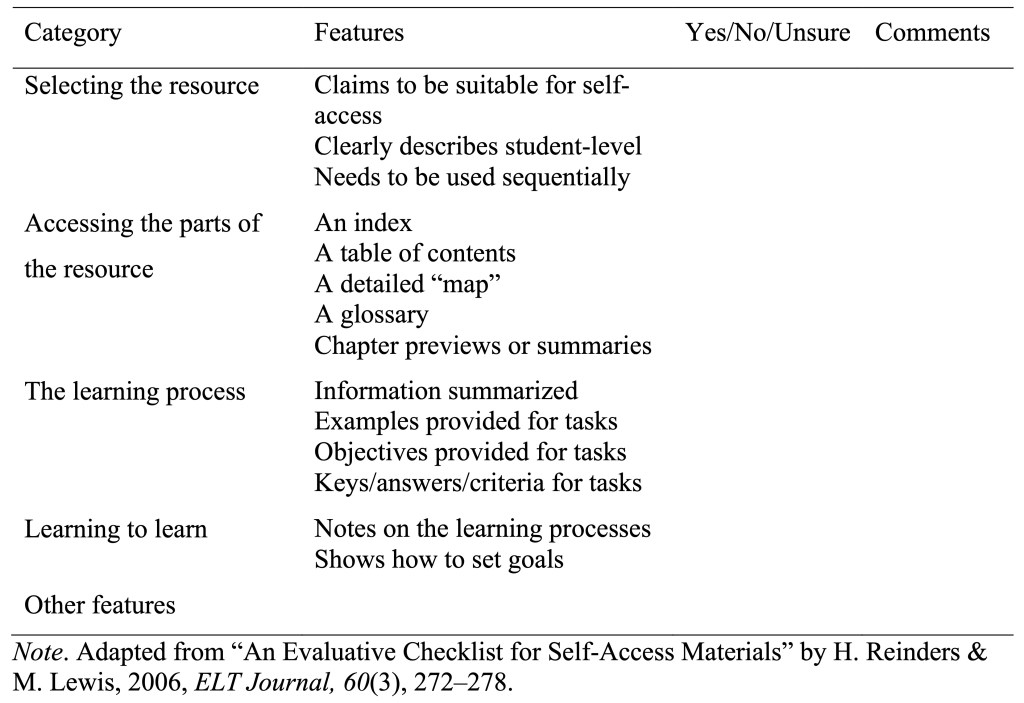

Learners who use SALC materials without teachers’ guidance must have clear, specific, and valid criteria for selecting and evaluating materials (Tomlinson & Masuhara, 2004). Studies have been conducted to establish such criteria for SALC practitioners, one example being the checklist developed by Reinders and Lewis (2006). In their study, Reinders and Lewis examined what students valued in published pedagogical materials within a SALC and generated a checklist based on students’ responses and a systematic review of the literature. Table 1 displays the resulting checklist.

Table 1

Checklist for Evaluating SALC Materials Developed by Reinders and Lewis (2006)

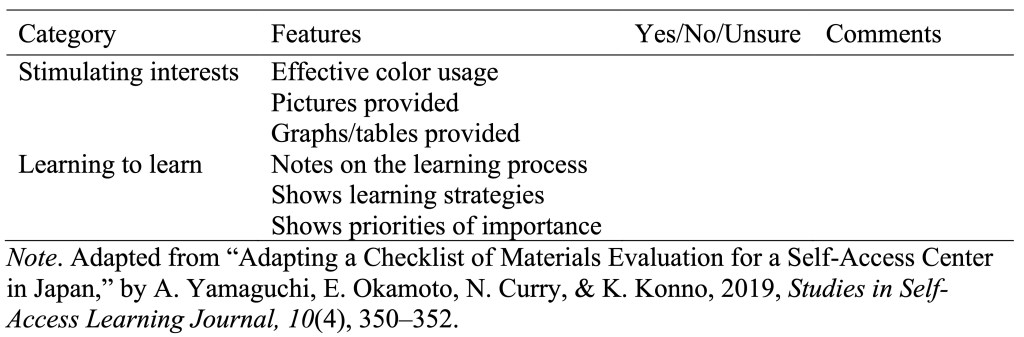

Reinders and Lewis’ (2006) checklist was further tested and adapted by Yamaguchi et al. (2019) in a SALC at a Japanese university. Their findings suggested that Japanese students value visually stimulating materials and need ones that offer explicit guidance to effectively use them outside the classroom. Thus, Yamaguchi et al. added a new category, stimulating interests, to incorporate the value placed on attractive materials by Japanese learners and modified the learning to learn category of the original checklist. Yamaguchi et al.’s new category and modifications are detailed in Table 2 below. Their checklist captures Japanese students’ perspectives on self-access materials. However, their examination only targeted professionally published materials and did not take into account those produced in-house by faculty or staff. This gap needs to be addressed for SALCs to optimally meet users’ needs, as they often offer both published and in-house materials. Our study targets this aspect through an analysis of learners’ perspectives on in-house materials in a particular SALC at a Japanese university. The present study was intended as preliminary research before engaging in larger-scale investigations.

Table 2

Addition and Modification to Reinders and Lewis’ (2006) Checklist by Yamaguchi et al. (2019)

Research Questions

To gain an understanding of learners’ (here, student staff members) perceptions and use of in-house supporting materials, we formulated two research questions (RQs):

RQ1: What factors are most important for the participants in their perception of SALC in-house materials?

RQ2: How can the factors highlighted by the participants be applied to future in-house material evaluation?

Methodology

This section details the methodology followed in this research. This paper focuses on one part of a larger investigation; here, we describe the details of the project as a whole. First, the context of the study and the participants (including the process and rationale for suggestion) are introduced. Descriptions of the data collection procedure and the analysis follow.

Context

This study was conducted at a SALC at a private university near Tokyo with approximately 4,200 students, all majoring in foreign languages, international communication, or global liberal arts. The SALC occupies a purpose-built, two-story facility. Several forms of support for autonomous language learning are available, such as opportunities for speaking and writing practice with lecturers, individual advising from full-time learning advisors, interest-based learning communities (see Watkins, 2022), events, and workshops. Additionally, over 5,000 published materials (e.g., books and DVDs) are available for students to use and borrow.

The SALC also offers its own in-house materials to aid learners’ autonomous language learning. These include more than 25 unique paper-based materials such as

- pamphlets listing recommended resources,

- pamphlets describing learning strategies, and

- self-diagnostic worksheets for users to evaluate their current strategy use or learning needs (see Appendix A for examples of the resources).

Additionally, the SALC’s website contains over 20 online materials, such as introductions to learning strategies or self-diagnostic worksheets.

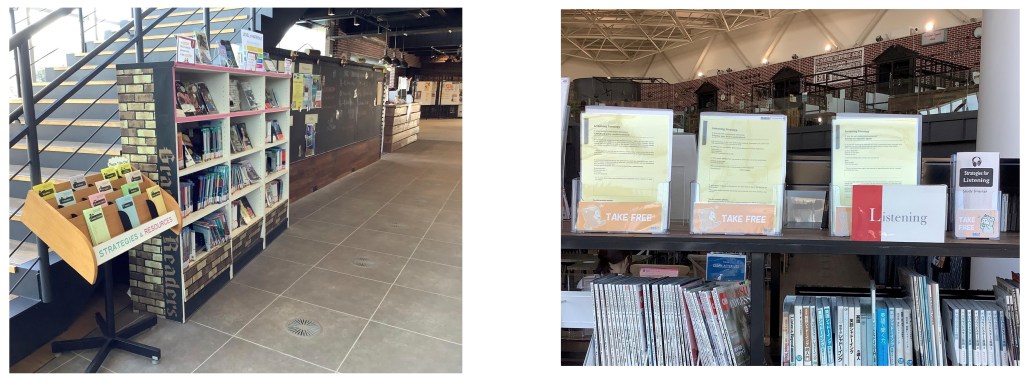

These in-house materials are developed by SALC learning advisors (for more on the development process, see Kershaw et al., 2010). Learning advisors review and revise the resource pamphlets annually, but the other materials are revisited less regularly, if at all. The materials are placed around the SALC and are freely available for users to take; the pamphlets are displayed together prominently near the front counter, while the other materials are dispersed throughout the center (e.g., near relevant resources; see Figure 1 for examples of how the materials are displayed).

Figure 1

Examples of In-House Material Locations in the SALC

The SALC is operated by learning advisors, administrative staff, and a team of paid student staff colloquially referred to as “SALCers” (Oki & Hall, 2022; Yamaguchi, 2011). At the time of the study, the SALC employed 35 SALCers representing multiple majors and years in the university. SALCers carry out administrative tasks, including performing front counter duties (e.g., helping users check out and return materials), counting SALC users for record-keeping purposes, and processing newly acquired materials. They also lead projects to improve the SALC, such as creating interactive displays or organizing events for fellow students.

Participants

The researchers focused on SALCers as participants for this initial study, before potentially later proceeding to research targeting the overall student population. The researchers emailed all SALCers to recruit participants. Nine volunteered to participate in the present research: four in the English department, three in International Communication, one in Chinese, and one in Spanish. Their length of working experience ranged from 6 months to 3 years. All participants gave consent for data use. It was felt that SALCers would be easier to recruit, as their investment in the SALC would make them eager to participate. Their frequent engagement with the SALC through both their official duties and personal use positioned them to offer more definitive opinions than general users, although their dual roles as staff and students may have introduced bias or elevated their metacognitive awareness (e.g., of the features of autonomous learning or the attributes of a useful SALC resource). In fact, in a separate exploratory stage of this research (not included due to space limitations), the researchers investigated how aware the SALCers actually were of the materials and the degree of their experience using them, with the aim of assessing how much the materials were being used. It was found that the SALCers were generally familiar with the existence and location of the materials. However, none of them reported having used the materials themselves.

Data Collection

To collect participants’ opinions, the researchers selected nine different in-house materials, which were representative of the various types available in the SALC. The researchers chose to analyze the paper-based materials because they are more prominently displayed and accessible in the SALC, making them more visible to users. Additionally, SALCers were more likely to have encountered these materials through their regular duties. The selection included three strategy pamphlets, two recommended resources pamphlets, and four strategy sheets (Appendix A contains samples of the selected materials).

The SALCers shared their opinions on the nine materials in group discussions held in classrooms within the SALC, in which they examined and reacted to the materials. Three discussions of approximately 45 minutes each were conducted in September 2022, and attended by four, two, and three participants, respectively.

A series of questions was formulated based on existing SALC material evaluation checklists (Reinders & Lewis, 2006; Yamaguchi et al., 2019) to guide the discussion. The discussions consisted of three sections: SALCers’ experiences with the materials, SALCers’ opinions of the materials, and SALCers’ suggestions to improve the materials (The first section applied to a portion of the research not covered here; see Appendix B for the discussion questions). Additionally, SALCers could examine and read the selected samples of the materials during the discussions. The discussions were video- and audio-recorded. The three researchers were present; two facilitated the session, while one observed and took notes, which were used to aid recall during transcription analysis. In the present publication, we analyze the data gathered from the second section.

Data Analysis

The first step of the data analysis involved transcribing the group discussions. We used the AI transcription website Otter (https://otter.ai), making corrections where necessary. The second step was a thematic analysis based on the checklist for self-access center material evaluation by Yamaguchi et al. (2019; adapted from Reinders & Lewis, 2006). We followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) procedure for coding, individually from Steps 1 to 3—becoming familiar with the data, generating initial codes (including our original codes), and searching for themes—and as a group from Steps 4 to 6: reviewing themes and codes, defining them (see Appendix C for the definitions), and reporting the findings.

Results

This section presents the findings of this study to answer each of the research questions.

RQ1: Factors Affecting Perceptions of In-House Materials

Following the thematic analysis of the transcripts, the results were examined to determine which criteria from Yamaguchi et al.’s (2019) checklist the participants referred to most often when inspecting and reacting to the materials. Figure 2 shows the overall themes that emerged from the discussions.

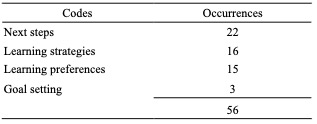

Of the criteria listed by Yamaguchi et al. (2019), the learning to learn criterion, which includes notes on the learning process, learning strategies, and priorities of importance, was the most frequently occurring theme (56 of 146 items coded). Table 3 displays a summary of the codes within this theme. Of these, the code next steps was most frequent (n = 22) and was applied when SALCers referred to suggestions within the material for its usage, possible next steps in the learning process, or a need for such elements. This pertained to statements such as Kota’s suggestion:

I didn’t actually know what to do after answering these [this] kind of questions.… So maybe it would be better if [it] … just says like, “talk to your learning advisor” at the top, and then students can answer these questions. They will know what to do.

Figure 2

Themes From Participants’ Reactions to Materials (N = 146)

For the SALCers, inclusion and explanation of specific learning strategies in the materials appeared to be a significant feature. For instance, when asked whether the materials help her to learn new strategies, Chie answered positively and commented on a worksheet’s value, in her case, referring to the How to Do Dictation worksheet (see Appendix A):

I have tried dictation when I was in high school…. And didn’t try even try to do the dictation in university. So, I think bring it back to my learning source to do the dictation and flashcard as well [is such a] helpful strategy.

Table 3

Codes in the Learning to Learn Theme

The SALCers also mentioned the importance of considering users’ learning preferences (n = 15). Referring to the materials’ function of supporting self-directed, independent learning, Sora said, “[At the university,] students, almost all of them prefer to talk, or some do study with [others], or they want to get some ideas from [others].… So there is only a few opportunities to use [these for independent learning].”

Conversely, the code goal setting, used for participants describing a material’s potential to support them in setting a learning goal, occurred least frequently (n = 3) in this theme. These figures may reveal the students’ preference for more specific, directive suggestions for their learning. This trend mirrors Yamaguchi et al.’s (2019) decision to eliminate Reinders and Lewis’s (2006) shows how to set goals criterion.

The second most frequent theme corresponded to the selecting the resource theme (33 out of 146 codes). Table 4 shows the codes within this theme and the number of occurrences.

Table 4

Codes in the Selecting the Resource Theme

Our codes did not match the criteria established by Reinders and Lewis (2006) or Yamaguchi et al. (2019) for this theme, as the target materials in this research differed fundamentally from those in the previous studies. Here, the theme covered codes referring to level of the text (n = 21; a code added in our data analysis) and objectives clearly labeled (n = 12). Regarding the former, some SALCers referred to the perceived (on first inspection) proficiency required for a material’s target user, regardless of whether that perception was accurate. For instance, Sora believed that for first-year students, “It seems…there is a lot of information and … seems very difficult.… Probably freshman don’t wanna try [these] materials.” Interestingly, upon closer inspection of the materials, several SALCers realized they might not be as difficult as initially thought. However, Yuna stated,

Maybe the reality is … even if freshmen or some student can see this kind of material, maybe they can understand [it], but … the looks, it seems like there are a lot of sentences, there are [is] a lot of information, so that’s why many students … hesitate to use them, I guess.

As for the latter code, objectives clearly labeled, participants tended to react positively when the target skill or user was apparent upon viewing the material, as seen in Akako’s statement: “These colorful materials are really easy to understand what [they are] for, but these pieces of paper look like difficult … But when students take a look, maybe they can understand, ‘Ah! This is for listening.’” These tendencies highlight the importance students place on clear indicators of the level and intended use of such materials.

The category stimulating interests, developed by Yamaguchi et al. (2019), was also represented (n = 24). Table 5 shows the codes categorized under this theme. The theme encapsulated students’ mentioning the inclusion (or lack) of pictures, appeal to their intrinsic interests, the use of color or a desire for more color, and the general attractiveness of a material.

Table 5

Codes in the Stimulating Interests Theme

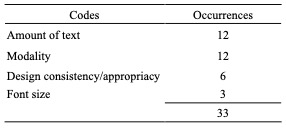

Table 6

Codes in the Designing the Material Theme

A fourth theme, which was not present in either version of the checklist, was revealed in the results and was labeled designing the material. Table 6 shows the codes categorized under this theme. It was the third most common, accounting for 33 of the 146 codes and surpassing stimulating interests. In this category, the participants referred to design-related factors such as the amount of text on the page (e.g., Nanako’s belief that “It makes me feel boring when there [are] many letters.”) or the modality of the material (e.g., when a student expressed the desire for a digital version of a material, rather than a paper one). The theme also covered the consistency or appropriacy of the materials’ design (n = 6), as in Akako’s difficulty distinguishing materials of different types. She noticed that materials meant for different purposes (e.g., worksheets suggesting strategies and those for self-diagnostics) appeared similar: “Maybe there are some laminated ones but the same color, white, in the same shape, so I didn’t think it’s [a] different one.” Students also commented on the font size (three occurrences), although not as often as the overall amount of text.

RQ2: Application of the Findings for Future In-House Material Evaluation

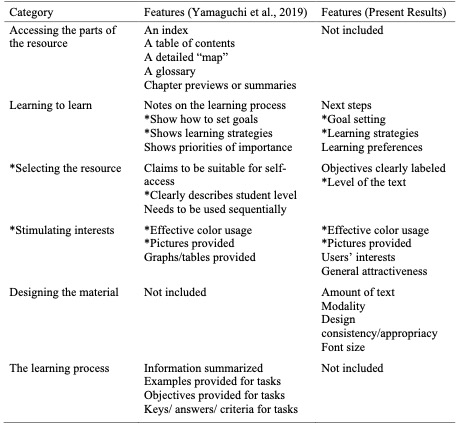

Based on our analysis of the discussions, we suggest that Yamaguchi et al.’s (2019) checklist can be adjusted in order to be applicable for evaluating SALC in-house materials. Table 7 (* represents elements common to both checklists) compares their checklist and the one that we developed after analyzing the SALCers’ answers.

The two versions have several similarities, which are marked with an asterisk and consist of common categories (four out of five) and criteria (five out of 23). Our checklist also differs from Yamaguchi et al. (2019) in the following ways: The categories accessing the parts of the resource and the learning process are absent from our checklist, while designing the material was added. Some items in the 2019 checklist are not included in our list (e.g., glossary, table of contents, keys, and tables provided from the accessing the parts of the resource category) because they did not apply to our in-house supporting materials. Furthermore, new criteria were added to our checklist (e.g., modality, font size, learning preferences).

Two categories, accessing the parts of the resource and the learning process, were omitted from our list as they directly refer to features of published pedagogical materials that do not apply to the materials in this study.However, we propose adding one new category, designing the material. This category encapsulates codes regarding the amount of text, the materials’ modality (e.g., whether they have online versions along with, or instead of, paper versions), the consistency and appropriacy of the design (e.g., whether similar materials have a recognizably uniform design or whether the design matches materials’ goal or purpose), and the size of the font.

Table 7

Comparison Between Yamaguchi et al. (2019) and the Present Results

Discussion

In this section, we discuss two prominent findings of the study: the importance of design and formatting and that of the learning to learn element in in-house materials.

Importance of Design and Formatting

The results show that design played a significant role in shaping the participants’ perceptions of the SALC materials. Various aspects of the design were mentioned often

enough by the SALCers that a discrete theme emerged, which was present in neither checklist drawn upon for coding (Reinders & Lewis, 2005, 2006; Yamaguchi et al., 2019). Some SALCers felt that the purpose or level of certain materials was unclear. Additionally, one participant expressed confusion over the inconsistency in material design (e.g., why certain ones were numbered but others were not). Consideration of visual design when creating or revising materials could make their purpose more immediately apparent, and a consistent design identity (e.g., use of branding elements or color) might allow for quicker recognition and distinction between materials. Participants also found visual elements such as illustrations and diagrams to be important; Chie believed that a material addressing learning with movies that consisted only of text contradicted the “fun and interesting” image of movies. She said, “If we have [a] picture and then the explanation on [the] text next to … or under that picture, then it’s more easy to understand.” Kota even specified how the use of rectangular text boxes made the materials look “serious.” These tendencies mirror Yamaguchi et al.’s (2019) conclusion that, at least for Japanese university learners, a pleasing appearance was an important factor in self-access materials. Visual design seemed to be a greater consideration here than in Reinders and Lewis (2006), and at least to a similar extent as in Yamaguchi et al.

An additional point regarding the materials’ design involves how it influenced the participants’ perceptions of the materials. In particular, when inspecting and reacting to the materials, they often referred to font size or the amount of text on the page. These factors contributed to their descriptions of the materials as too difficult or boring, as in Midori’s belief that “it’s kind of scary to read a lot of letters, especially for freshmen.” In turn, these beliefs affected their opinions on the level of the material (21 occurrences in the theme selecting the material) and the perceived interest, as in Chie’s belief that “if we like talking about movies, we want to make it more fun and interesting. But if we have much text, then we think [the material is] not [about] movies.”

Furthermore, the materials’ modality was referred to often (12 occurrences in reaction to the materials and seven when suggesting improvements), such as participants’ mentioning human or digital alternatives or expressing a desire for online versions. This preference is unsurprising in the current learning context, where all students own mobile devices such as iPads or laptops and have constant internet access. The importance of convenient, mobile-friendly learning tools available on-demand has likely become dramatically more salient to learners since the development of Reinders and Lewis’s (2006) or Yamaguchi et al.’s (2019) checklists. In addition, factors such as visual design and modality may now carry greater weight than they did when the previous checklists were developed, reflecting the rapid evolution of mobile and digital technology and the ways learners have integrated these tools into their lives., As “digital natives,” current university students have grown up with interactive, multimedia-rich environments (Chen, 2024) and may engage with learning materials differently than previous generations. Japanese youth value efficiency and convenience in digital content and are accustomed to consuming authentic, personalized, and interactive content (Kanaya, 2024; Lou, 2023; Ulpa, 2024); these factors could possibly lead them to prioritize digital materials for learning on the go.

As mentioned, the SALC offered digital materials on its website at the time of writing, but these did not appear to meet the participants’ preferences. Many were developed during the Covid-19 pandemic as a way to support learners while the SALC was offering services solely online (Davies et al., 2020), while others are merely PDF versions of existing paper-based resources and thus may not fully exploit the affordances (e.g., interactivity, personalizability, multimedia integration, or ease of navigation) of digital formats. Additionally, anecdotally, from the writers’ experiences, awareness of these digital resources is even lower than that of the paper-based ones in this study. This contrast between learners’ apparent preference for digital, mobile-friendly materials and their limited engagement with the SALC’s current digital offerings suggests a gap that warrants further attention. Future development of digital resources should not only expand their availability but also ensure they are aligned with learners’ expectations for convenience, interactivity, and design, while also taking into consideration the ways that learners navigate to new resources or media, as well as possible needs for awareness-raising. These needs also present an important avenue for future research.

Interestingly, SALCers’ opinions regarding the proficiency required to use materials were only based on their initial reactions to the materials; upon closer inspection, some SALCers were able to amend their first reactions, reflecting their revised perceptions of the materials, and suggesting potential improvements. Their first impression appeared to have been a reaction to the sheer amount of text (in a relatively small font) on the page. This result underlines the importance of awareness of the size and amount of text when designing in-house materials, which in turn raises a dilemma. As those such as Sinclair (1996) noted, with the inherent absence of teachers to guide learners, self-access materials with a learner-training function may require additional explanation than pedagogical materials. However, if the very perception of that added explanation makes learners hesitate to approach those materials, such text becomes counterproductive. Careful consideration will be required to negotiate this balance when revising these materials or designing new ones.

Moreover, as SALCers are typically highly motivated and autonomous learners, it is unclear whether general SALC users would react even more strongly to the materials. It is also important to consider that their position as both staff and students may have influenced how they engaged with the materials and framed their feedback. This dual perspective may have shaped their interpretations in ways that differ from typical users, potentially leading to more reflective or critically informed responses that do not necessarily represent the broader student experience. Countermeasures (e.g., creative use of type and layout) should be devised and tested with actual learners. Additional exploratory research is needed to determine how learners interact with printed materials and whether support could reasonably be provided in other modalities (e.g., online videos). A clear implication of these results is that design should be accounted for when developing in-house materials. One encouraging point is that as these materials were produced in-house, SALC faculty and staff certainly have more control over them than with published materials. Building on this advantage, SALCs could implement practical measures such as conducting periodic reviews of in-house materials and involving learners in the design process to better meet their needs. These steps can contribute to creating more effective and learner-centered materials.

Learning to Learn: Perceived Importance and Further Support

The findings suggested that our participants viewed learning to learn as a particularly important element in the in-house materials. This contrasts with Yamaguchi et al. (2019), which showed that some higher-order functions of materials were less salient to their Japanese learners. One explanation for this is that the materials we examined in this study were in-house materials that inherently focus on the learning process (e.g., choosing resources, self-evaluating their own learning, and learning the steps to do activities such as dictation; see Appendix A for examples). Another factor that possibly contributed to this difference is the fact that the participants were not merely students but SALC student staff who received training to understand the SALC’s purpose of fostering learner autonomy in students.

Among the codes under the theme of learning to learn, our participants paid the most attention to next steps. Their comments suggested that students may have difficulty deciding what to do after using the in-house materials. With our strategy self-evaluation pamphlets, which provide questions that help students evaluate how they study, some SALCers “didn’t actually know what to do after answering these [self-evaluation] questions,” as Kota said. Teachers may easily assume students would see how to improve their learning after reviewing such evaluation questions. For example, if they answer“rarely” to the question “Do you choose texts appropriate to your level?” it may appear evident that they would then know to start choosing reading materials carefully. However, some participants’ comments suggest this process may be challenging for many learners. In fact, to select reading materials that match their level, learners must first know what is “appropriate” for their level. The answer may differ depending on the learning purpose. For instance, if students wish to improve their reading fluency through extensive reading, it is recommended that they choose a book for which they already know 98% of the vocabulary (Nation & Waring, 2020). On the other hand, if learners engage in academic reading to gain knowledge about a given topic, the material will likely contain more unknown vocabulary. Once they figure out the level, learners need to find materials at that level, which is another challenge, according to the SALCers in this study. Furthermore, trying new resources could be emotionally demanding for learners even after locating them. They may easily fall back on the resources they are already familiar with (Ubukata & Ying, 2023).

In light of such possible challenges that learners face, the results highlight the importance of optimally utilizing in-house self-access materials by connecting them with other resources available in a SALC (Kershaw et al., 2010). In this sense, human resources may be the key to bridging in-house materials and learners’ successful learning in terms of learning to learn,including support for finding their next steps. For the SALCers who participated in this study, learning advisors seem to play an important role in providing support that matches learners’ specific needs, as Sora stated: “If I have to use these materials, first of all, I reserve … learning advisors.… I think I can use these materials more effectively rather than do that only one.” As some of the in-house materials include notes encouraging learners to talk to learning advisors, other materials could also benefit by emphasizing this point.

Conclusion

This study examined students’ perspectives on our SALC in-house supporting materials. The results highlighted the importance of carefully considering design aspects such as consistency, illustrations, font and amount of text, and modality. The findings also suggested that in-house materials should facilitate the learning process, for example, by providing next steps and accommodating learners’ learning preferences. Addressing those would make SALC resources more attractive and relevant and improve accessibility and inclusiveness for all users (as suggested in Pemberton et al., 2023).

Several limitations in the study need to be noted. First, regarding the participants, they were not general SALC users but student staff trained to have a shared understanding of the SALC and to support other students’ learning in the facility. Thus, the results may not be generalizable to typical SALC users. Future research could address these gaps by involving regular students and observing their interactions with the materials or gathering feedback after extended use. Second, limitations exist related to the group discussions. During the hands-on parts of the discussions, the SALCers often viewed the materials closely for the first time, and their opinions were based solely on those initial reactions. Additionally, the researchers were present during these discussions, and as senior figures in the SALC, their presence may have influenced participants’ responses. This influence could have introduced social desirability bias or hesitation on the participants’ part to offer critical feedback. Finally, regarding methodological shortcomings, the checklist by Yamaguchi et al. (2019), used for analysis due to the lack of research on in-house self-access materials, was designed for different types of materials, making direct comparisons difficult. Future research could ideally be based on a checklist specifically developed for in-house materials.

Based on the findings, SALC practitioners (e.g., faculty or administrative staff) developing or providing in-house supporting materials should regularly assess users’ voices and evolving needs through different means, such as discussions and surveys. In addition, we suggest frequently evaluating and updating those materials using a checklist, such as the one developed in this research. Raising awareness among users, staff, and faculty through orientation and workshops would also be necessary. As suggested by Rowberry (2004), simply making materials available around the SALC is insufficient to ensure their adoption by learners. At the same time, the material development and evaluation process has challenges. Creating or updating in-house materials presents an additional workload and may not be easily feasible with limited staff availability. The need to meet a diverse range of learners’ preferences and needs may present further challenges to practitioners. Depending on the context, copyright issues are another restriction; for example, in our context, copyright laws heavily restrict the use of commercial images. To overcome such difficulties, it is crucial to bring together teachers and administrative staff and effectively leverage their expertise.

Notes on the Contributors

Haruka Ubukata is a Learning Advisor at the Self-Access Learning Center at Kanda University of International Studies. She has completed the Learning Advisor Education Program at the Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education. She holds an MSEd from Temple University, Japan Campus.

Emily Marzin is a Learning Advisor at the Self-Access Learning Center at Kanda University of International Studies. She has completed the Learning Advisor Education Program at the Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education. She holds a master’s in didactics from Jean Monnet University, France and an EdD from the Open University, UK.

Isra Wongsarnpigoon is a lecturer in the Faculty of Global Liberal Arts at Kanda University of International Studies and a former Learning Advisor in the Self-Access Learning Center at the same institution. He holds an MSEd from Temple University, Japan Campus. His interests include multilingualism and translanguaging in language learning, learning spaces and environments, and learner autonomy.

References

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Chen, Z. (2024, July 16). The Satori Generation: Minimalism and economic caution in modern Japan. Woke Waves. https://www.wokewaves.com/posts/satori-generation-japan-minimalism-economic-caution

Davies, H., Wongsarnpigoon, I., Watkins, S., Vola Ambinintsoa, D., Terao, R., Stevenson, R., Imamura, Y., Edlin, C., & Bennett, P. A. (2020). A self-access center’s response to COVID-19: Maintaining stability, connectivity, well-being, and development during a time of great change. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 11(3), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.37237/110304

Domínguez-Gaona, M., López-Bonilla, G., & Englander, K. (2012). Self-access materials: Their features and their selection in students’ literacy practices. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(4), 465–481. https://doi.org/10.37237/030410

Edlin, C., & Imamura, Y. (2018). Resource coordination in the Self-Access Learning Center at Kanda University of International Studies for the 2017–2018 academic year: Activity, concept, and expanding definitions. Relay Journal, 1(1), 178–196. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010119

Everhard, C. J. (2022). There’s something about SALL: A response to Gardner and Miller. Relay Journal, 5(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/050103

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (2021). After “Establishing…”: Self-Access learning then, now and into the future. Relay Journal, 4(2), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/040202

Kanaya, R. (2024, June 18). Unveiling the trends of social media usage among Gen Z in Japan. Uism. https://uism.co.jp/en/unveiling-the-trends-of-social-media-usage-among-gen-z-in-japan/

Kershaw, M., Mynard, J., Promnitz-Hayashi, L., Sakaguchi, M., Slobodniuk, A., Stillwell, C., & Yamamoto, K. (2010). Promoting autonomy through self-access materials design. In A. M. Stoke (Ed.), JALT2009 Conference Proceedings (pp. 151–159). JALT. https://jalt-publications.org/archive/proceedings/2009/E012.pdf

Lou, J. (2023, December 14). Spoiler alerts and double speed: The Japan Gen Z’s unique approach to content consumption. Medium. https://medium.com/@jamie_aix/spoiler-alerts-and-double-speed-the-japan-gen-zs-unique-approach-to-content-consumption-885170684e34

Mynard, J. (2024). Self-access language learning support in Europe: Observations and current practices. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(2), 258–279. https://doi.org/10.37237/150209

Mynard, J. Ambinintsoa, D. V., Bennett, P. A., Castro, E., Curry, N., Davies, H., Imamura, Y., Kato, S., Shelton-Strong, S. J., Stevenson, R., Ubukata, H., Watkins, S., Wongsarnpigoon, I., & Yarwood, A. (2022). Reframing self-access: Reviewing the literature and updating a mission statement for a new era. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 13(1), 31–59. https://doi.org/10.37237/130103

Nation, I. S. P., & Waring, R. (2020). Teaching extensive reading in another language. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367809256

Oki, M., & Hall, M. (2022, October 22). SALC no rinen ni motozuita yuukyuu gakusei staff (SALCer) saiyou katsudou to shinjin training no hensen [Recruitment of paid student staff (SALCers) aligned with SALC philosophy and transition of new staff training] [Conference presentation]. Japan Association for Self-Access Learning 2022 National Conference, Akita, Japan.

Pemberton, C., Marzin, E., Mynard, J., & Wongsarnpigoon, I. (2023). Evaluation of SALC inclusiveness: What do our users think? JASAL Journal, 4(1), 5–31. https://jasalorg.com/evaluation-of-salc-inclusiveness-what-do-our-users-think/

Reinders, H. (2012). Self-access and independent learning centers. In C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), The encyclopedia of applied linguistics (pp. 5166–5169). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal1059

Reinders, H., & Lewis, M. (2005). Examining the self in self-access materials. REFLections, 7, 46–53. https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/reflections/article/view/114315

Reinders, H., & Lewis, M. (2006). An evaluative checklist for self-access materials. ELT Journal, 60(3), 272–278. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccl007

Rowberry, J. (2004). Developing in-house materials for the self-access learning centre. Kanda University of International Studies: Working Papers in Language Education, 1, 213–226.

Sinclair, B. (1996). Materials design for the promotion of learner autonomy: How explicit is ‘explicit’? In R. Pemberton, E. S. L. Li, W. W. F. Or, & H. D. Pierson (Eds.), Taking control: Autonomy in language learning (pp. 149–165). Hong Kong University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2jc12n.18

Thornton, K. (2024). Focusing on the future of SALL: A response to Stacey Vye. Relay Journal, 7(1), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/070105

Tomlinson, B., & Masuhara, H. (2004). Developing language course materials. SEAMEO Regional Language Centre.

Ubukata, H., & Ying, A. (2023). Japanese university students’ self-directed learning goals and action plans elicited with the use of a reflection tool. Relay Journal, 6(2), 123 –149. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/060203

Ulpa. (2024, November 2). Mastering youth culture: The increasing influence of Gen Z in Japan. https://www.ulpa.jp/post/mastering-youth-culture-the-increasing-influence-of-gen-z-in-japan

Watkins, S. (2022). Creating social learning opportunities outside the classroom: How interest-based learning communities support learners’ basic psychological needs. In J. Mynard & S. Shelton-Strong (Eds.), Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom: A self-determination theory perspective (pp. 109–129). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788929059

Yamaguchi, A. (2011). Fostering learner autonomy as agency: An analysis of narratives of a student staff member working at a self-access learning centre. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 2(4), 268–280. https://doi.org/10.37237/020404

Yamaguchi, A., Okamoto, E., Curry, N., & Konno, K. (2019). Adapting a checklist of materials evaluation for a self-access center in Japan. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 10(4), 339–355. https://doi.org/10.37237/100403

Appendices

See PDF version