Misato Saunders, Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University, Japan. https://orcid.org/0009-0009-1644-1277

Osamu Takeuchi, Kansai University, Japan. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5195-992X

Saunders, M., & Takeuchi, O. (2025). Exploring perspectives of language advisors and advisees about language advisors’ roles in a Japanese university context. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(2), 342–359. https://doi.org/10.37237/160205

Abstract

The concept of roles of language/learning advisors (LAs) at self-access learning centers (SALCs) is often elusive. While some literature distinguishes LAs from language teachers (LTs), others argue that LAs fulfill multiple roles, including those of advisor, teacher, and coach despite the title “advisor.” Although there have been discussions about LAs’ roles from their perspectives, advisees’ viewpoints remain largely unexplored. Therefore, this study investigates the roles of LAs from both LAs’ and advisees’ perspectives. Utilizing Thompson’s (2017) Coaching Impact Model, which conceptualizes advising, teaching, mentoring, and coaching as a spectrum of shifting roles, this study examines how both LAs and their advisees perceive these roles. In the context of a Japanese university, semi-structured interviews were conducted with two LAs and four advisees to delve into their perceptions of LA roles. The findings revealed that advisees’ views of their LAs’ roles evolved as they became more autonomous in their learning. These findings suggest that LAs’ roles should not be confined to a single role. Instead, LAs could adapt their approach, shifting between the roles of advisor, teacher, mentor, and coach, depending on the advisee’s autonomy level.

Keywords: Language/Learning Advisor (LA)’s role, autonomy, coaching impact model

Advising in language learning (ALL) is a relatively new area of applied linguistics. ALL is defined as a dialogic process in which language/learning advisors (henceforth LAs) support learners’ reflection and decision-making, to promote autonomy in one-to-one sessions (Kato & Mynard, 2016). Benson (2011), among others (Holec, 1982; Little, 1999), emphasized the need for learners to take control of their learning, establishing autonomy as essential in language learning.

To foster learner autonomy, LAs play a pivotal role. Unlike language teachers (LTs), they are not involved in the curriculum (Kato & Mynard, 2016) but support learners across various learning pathways (Mozzon-McPherson, 2007). Additionally, Kato and Mynard (2022) caution that adopting a teacher-like stance can hinder autonomy by creating power imbalances. Consequently, some LAs prefer roles like ‘mentor’ or ‘coach’ rather than ‘advisor’ or ‘teacher.’ However, Moriya (2018) describes the ambiguous boundary between LTs and LAs.

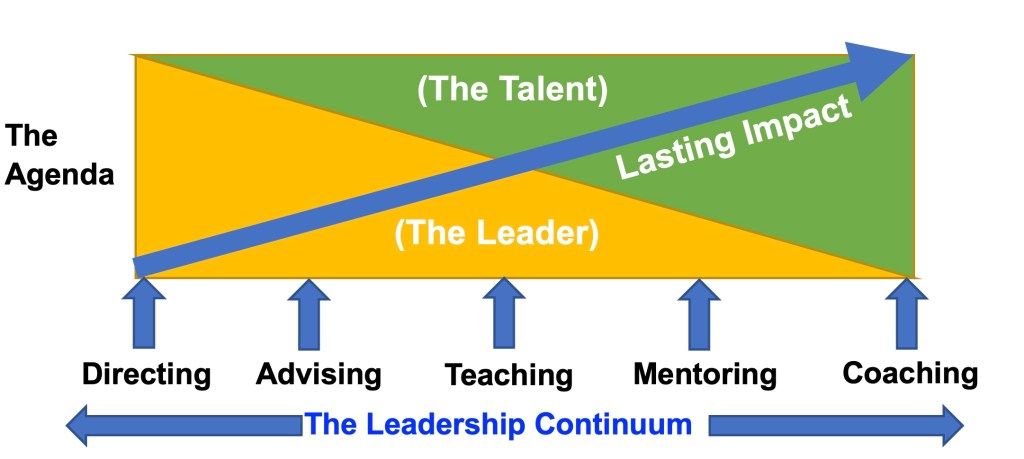

Despite the controversy, since each self-access learning center (SALC) has its own context (Gardner & Miller, 1999), it is hard to gain a universal consensus regarding the roles of LAs. Meanwhile, Thompson’s (2017) Coaching Impact Model presents a continuum of roles—where the talent (i.e., advisee) gradually gains control of the agenda (i.e., the problem that an advisee faces). At the coaching stage, the talent has full ownership of the agenda which fosters a sustainable impact. (Thompson, 2017; see Figure 1). This model offers a fresh perspective on LAs’ roles.

Although some discussions exist from the LAs’ perspectives, it is even more crucial to understand how advisees understand LAs’ roles than LAs do because Kato and Mynard (2015) state if advisees see LAs as tutors, they are more likely to repeatedly seek quick answers rather than engage in deeper reflection. Thus, how advisors and advisees perceive LAs’ roles is critically important for fostering autonomous learners.

While some studies explore how LAs perceive their roles, to our knowledge, limited research examines how advisees view their LAs’ roles. Gaining insight into advisees’ perspectives on their LAs’ roles may provide clues about how they perceive LAs and what they expect from them. Therefore, using Thompson’s Coaching Impact Model, the authors decided to investigate the perspectives of both LAs and advisees, examining any potential incongruencies between them. The study was conducted at a mid-sized private university with a SALC institute in Japan, adopting a phenomenological approach (van Manen, 1990) to capture individual experiences and undercover insights related to the research questions.

Literature Review

Learner Autonomy

Building on Holec’s (1981) foundation definition of learner autonomy as learner responsibility, Benson (2011) and Little (1991) further emphasized autonomy as the ability to think critically, make decisions, and take charge of one’s own learning. Benson and Lamb (2021) mentioned that having choices encourages learners to take responsibility for their learning through dialogue and resources. In the context of ALL, advisees can be given opportunities to engage in critical reflection and decision-making through one-to-one dialogue.

Advising in Language Learning (ALL)

In the context of ALL, intentional reflective dialogue (IRD; Kato, 2012) has been widely adopted as a common approach among LAs. The goal of IRD is to enhance the advisee’s awareness of their learning process through dialogue by employing techniques such as repeating, summarizing, powerful questioning, and challenging (Kato & Mynard, 2016; Kelly, 1996). This approach encourages advisees to engage in deeper reflection on their language learning journey and transform them toward autonomous learners.

Language/Learning Advisors’ (LAs’) Roles

The ultimate goal of an LA is to foster learner autonomy (Carson & Mynard, 2012). However, many advisees regard LAs as tutors and tend to seek quick answers to their questions without taking responsibility for their learning (Kato & Mynard, 2022). Therefore, it is essential to clarify the differences in roles and expectations at the outset of the advising relationship (Riley, 1997). Despite the nomenclature of ‘advisor,’ LAs fulfill distinct roles, such as language counselor, language coach, or mentor (Kato & Mynard, 2016). Additionally, Morrison and Navarro (2012) note the challenges and importance of transitioning from LT to LA. Conversely, Moriya (2018) acknowledges the ambiguity in the boundaries between LA and LT, discovering additional roles such as researcher role, and senpai (senior) role during advising sessions. However, not many LAs support maintaining ambiguity about the roles of LA and LT.

Continuum Roles Toward Coaching

To explore the roles of LAs from a coaching perspective, Thompson’s (2017) Coaching Impact Model (see Figure 1) may provide valuable insights for rethinking the role of LAs, even though it is not specifically designed for the context of ALL. This model originates from leadership studies and posits a leader (i.e., an LA) does not always need to adopt a coaching stance, even though coaching is considered the most effective approach to foster long-term sustainable impact for the talent. Thompson positions directing, advising, teaching, mentoring, and coaching as points along a leadership continuum, with coaching being the ideal method for developing the talent. He further emphasizes that leaders should flexibly adapt their roles—shifting between directing, advising, teaching, mentoring, and coaching—depending on the needs and circumstances of the individuals. Additionally, Ito (2017) has a similar idea to Thompson’s concept and highlights that coaching is not always universally effective for all clients. He emphasizes that it is more practical to have an experienced person teach inexperienced learners to handle a challenging task rather than adopting a coaching approach. As such, the roles of LAs should be tailored to the specific needs and context of the learners. Ultimately, the realization by learners that they are the core of their language learning journey and the acknowledgment of their responsibility in this process marks a pivotal moment.

Figure 1

The Coaching Impact Model (Thompson, 2017, p. 41)

Note. The talent refers to the individual who is receiving coaching and the leader is a coach. At the Directing stage, ownership of the agenda— including the issue at hand, the decision, the challenge, the opportunity, and the Talent’s performance or aspirations, rests entirely with the leader. As the process moves through the Advising, Teaching, and Mentoring stages, the talent gradually assumes greater ownership. At the coaching stage, the agenda is fully controlled by the talent, fostering long-term, sustainable impact (Thompson, 2017, pp. 39—41).

Considering the model, at the coaching stage, the talent takes full ownership of the agenda, including decision-making and addressing challenges. In other words, this stage represents the highest level of autonomy for the talent. The Coaching Impact Model suggests that the leaders (LAs) should also undergo this transformation alongside the talents (advisees), experiencing and sensing this shift throughout the language learning advising process. Therefore, using this model, the authors aim to explore how LAs and advisees perceive the roles of LAs, and to identify any gaps between their perspectives. Based on this perspective, the authors formulate the following research questions:

- What are the beliefs and perspectives of LAs toward their roles?

- What are the beliefs and perspectives of advisees toward LAs’ roles?

- Are there any incongruencies between LAs’ and advisees’ beliefs and perspectives about the role of LAs?

Through these research questions, the authors explore the gap between LAs’ and advisees’ perspectives on the role of LAs.

Methods

Research Design

A qualitative approach was adopted to uncover LAs’ and advisees’ beliefs and perceptions. Acknowledging the inherent subjectivity involved in qualitative research, emphasized by Charmaz (2014, 2020), the authors adopted a phenomenological stance, as advocated by van Manen (1990). According to this stance, it is essential to distill a person’s experience of a phenomenon into a description of its universal essence (van Manen, 1990). In this study, semi-structured interviews were employed as they enable the exploration of personal experiences, attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs of participants on topics of interest (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). In addition, follow-up online questions were asked after completing the second round of interviews with the advisees.

Following Otani (2022), the interviews were analyzed using the Steps for Coding and Theorization (SCAT) method. Codes were generated and categorized to construct a storyline for member checking.

Context of the University and the SALC for the Research

This study focuses on a single university, as each SALC operates under distinct missions and policies (Gardner & Miller, 1999), making comparisons challenging. The SALC in this study promotes three core goals: (1) language proficiency, (2) learner autonomy, and (3) intercultural competence. Among these, the emphasis on intercultural competence is particularly distinctive. The first author serves as both a language teacher and a language advisor at the university, offering insider insight into the institution and its SALC. This mid-sized private university in Japan offers programs in Asian Pacific studies, management, and tourism, with a balanced mix of international and domestic students. Since its establishment in 2011, the SALC has supported multilingual and multicultural learning beyond the classroom, aligned with its threefold mission above.

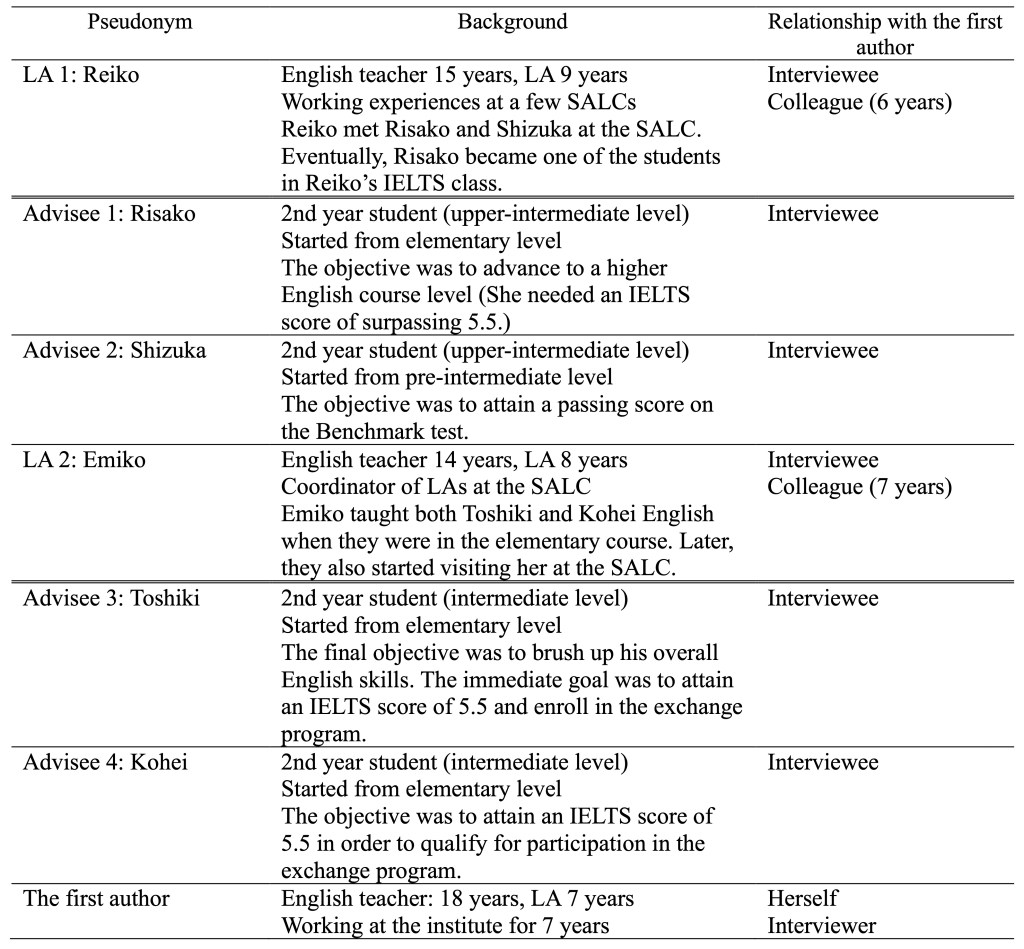

Participants

In the context of a phenomenological study, the appropriate sample size typically ranges from 3 to 15 individuals, as suggested by Creswell and Poth (2016). Patton (2015) advises specifying a minimum sample size based on the expected reasonable coverage of the phenomenon, considering the study’s purpose. Following these suggestions, the study involved two LAs and four advisees from the university (see Table 1). The LAs, Reiko and Emiko, had extensive experience as LTs and LAs and had worked closely with the first author for many years. Risako and Shizuka were advised by Reiko, while Toshiki and Kohei had been Emiko’s advisees for over a year. Opportunity sampling (Jupp, 2006) was used to recruit advisees who met specific criteria: advisees who attended advising sessions at least once or twice a week for more than two consecutive months which could include online sessions and email interactions due to the ongoing impact of COVID-19. Ethical approval (#22-45) was obtained from the ethics committee of the author’s institution, and participants were informed of their voluntary involvement.

Table 1

Background of Participants and the Relationship With the First Author

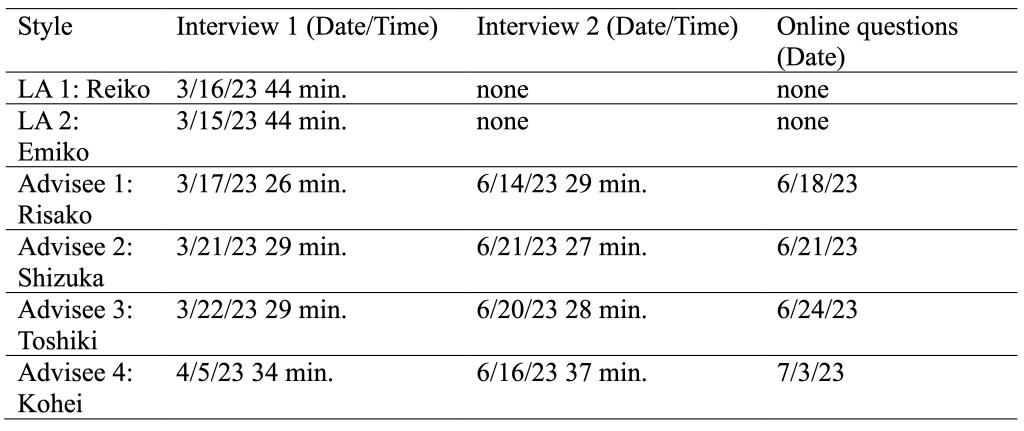

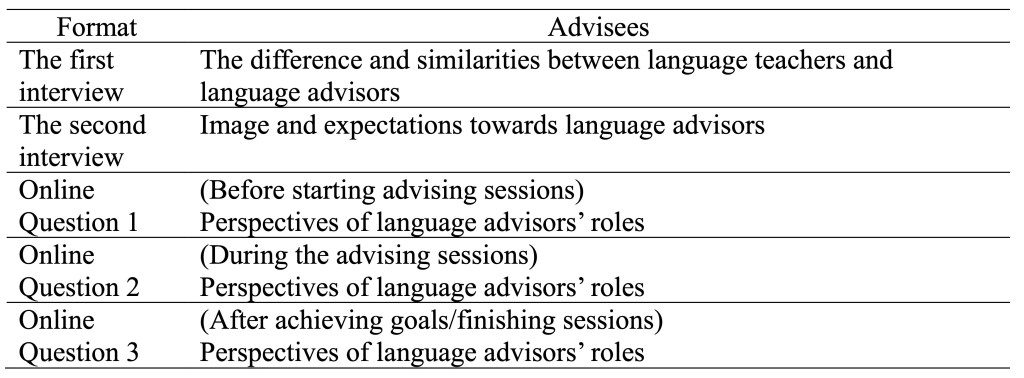

Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews and subsequent online questions were conducted in different styles for LAs and advisees. Table 2 provides details on the interviews, including dates, times, and the style of the data collection.

Examining Table 2, each LA underwent only one interview, while the advisees had a second round of interviews to explore the LAs’ roles in greater depth. All interviews and questionnaires were conducted in Japanese, the participants’ L1 to provide a more comfortable environment for participants to express their beliefs and perspectives.

Table 2

Interview Date, Duration, and Style of the Data Collection

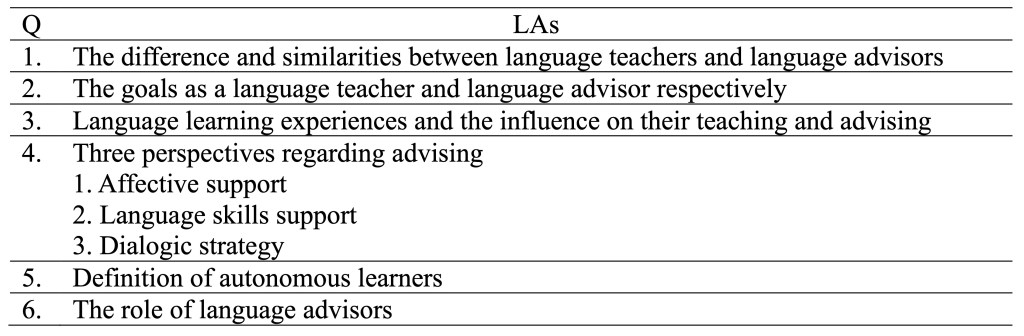

Interview Questions

As there were two types of interviews—one for LAs and the other for advisees—the authors needed to create the interview questions accordingly. The first author conducted interviews based on the questions in Tables 3 and 4. In the first round of interviews, both LAs and advisees were queried regarding distinctions and commonalities between LTs and LAs. This focus was crucial as the delineation between the roles of LTs and LAs holds significant importance for the LA’s responsibilities (Moriya, 2018; Morrison & Navarro, 2012). In Q5 of Table 3, LAs were asked about their beliefs regarding autonomous learners, as fostering learner autonomy is a key goal for LAs. In Q6 of Table 3, they were asked about the role of LAs based on Thompson’s Coaching Impact Model, which illustrates a continuum of roles toward coaching. Although Thompson’s Coaching Model includes the ‘Directing’ role, the author excluded the ‘Director’ role, which has complete control of the agenda. In LA sessions, advisees initiate discussions by bringing their own concerns, and therefore bear at least some control of the agenda. The director’s role is irrelevant in the context of ALL. The authors provided LAs with definitions of advisor, teacher, mentor, and coach and asked them to identify which role they believed best aligns with that of an LA before asking Q5. Meanwhile, in the second round of interviews, advisees were asked about their perceptions and expectations of LAs, which contributed to clarifying how they envision the roles of LAs. Additionally, the advisees completed three online descriptive questions that represented the same role definitions shown to the LAs.

Table 3

Interview Questions for LAs

Table 4

Interview Questions for Advisees

The definitions of roles were as follows:

- Advisor: Understands the situation from a third perspective and provides professional advice and objective guidance.

- Teacher: Shares expert knowledge and know-how with learners who have less experience.

- Mentor: Facilitates advice and dialogue between the mentor and mentee, allowing the mentee to gain insights from the mentor’s higher expertise.

- Coach: Clarifies the gap between the current state and the desired state, facilitating problem-solving through dialogue and supporting goal achievement.

The definitions were mainly referred to from Thompson (2017, pp. 11–15) and Ito (2017, p. 28), who belongs to the International Coach Federation (ICF). Although Thompson declared, “Coaching is not advising others, providing feedback, teaching skills, and solving problems” (p. 35), but continued, “Unfortunately, most contemporary approaches to coaching are essentially some combination of problem-solving and action-planning processes” (p. 6). Therefore, the concept of coaching from the ICF was adopted as a general coaching definition. As for advisors, Kato and Mynard (2022) distinguish between ALL and general advising, drawing an analogy to financial advising, where experts provide professional advice and information.

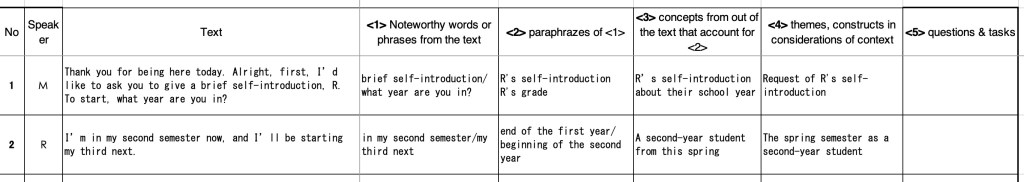

Instruments and Analysis

After the interview, all recordings were transcribed using an application called Notta.ai, and the authors cross-referenced the recorded voice with the transcription and rectified any discrepancies. As the next step, a SCAT sheet (see Figure 2) was used as an analytical instrument for the text data, as it provides clear procedural steps for coding and is particularly useful for small data sets (Otani, 2022). Following the generalization of codes, a storyline—sentences structured with a clear awareness of cause-and-effect relationships between events—was constructed based on the coded data and shared with each participant for member checking. This process aimed to identify and rectify any potential misunderstandings between the participants and the authors. To ensure coding accuracy, the first author conducted inter-rater reliability checks with two language teachers from the same university. Acting as the primary coder, the first author coded and labeled the data. Based on the codes, the second coder and the third coder labeled them independently. The concordance rate was 86.51% with the second coder and 81.81% with the third coder. As a few discrepancies emerged, they had discussions and arrived at the most fitting codes.

Figure 2

An Example of SCAT Sheet

Findings

Codes and Categories

There are eight categories that emerged for LAs:

- Language learning experiences (studying abroad, language learning strategies, affective experiences)

- Learner’s beliefs (beliefs formed through learning experiences)

- Metacognitive aspect (goal-setting, current status assessment, learning plan formulation, plan revision, reflection)

- Cognitive aspect (actions in learning, securing resources, learning strategies, training, application)

- Affective aspect (motivation, emotions/feelings, self-efficacy, sustained effort, rapport building, praise, encouragement, creating a comfortable and approachable atmosphere)

- Beliefs as an LA (the definition of autonomous learner, learner independence, LA’s roles)

- Beliefs about language teachers (perceptions of office hours, perceptions of group lessons)

- Common beliefs about both LAs and language teachers (LA role, teacher role, mentor role, coach role, skills of LAs, learner autonomy)

Concerning advisees, five categories were established:

- Perspectives toward Ls (LAs’ roles, reflection on LAs, characteristics, and images of LAs)

- Affective support (motivation, emotions/feelings, confidence, self-efficacy, sustained effort, rapport building, praise, encouragement, a sense of being supported, creating a comfortable and approachable atmosphere, curiosity)

- Metacognitive support (goal-setting, current status assessment/sharing, study plan formulation, plan revision, reflection, raising/promoting self-awareness, autonomy)

- Cognitive support (action, learning strategies, training, application)

- Perspectives toward language teachers compared to LAs

Answer to RQ1. What Are the Beliefs and Perspectives of LAs Toward Their Roles?

When the first author inquired which role is close to the LA’s roles, providing them with definitions for advisor, teacher, mentor, and coach, each LA responded uniquely. Reiko (LA1) stated that she fulfills all of the roles, saying, “I think I’m doing all of them” (Excerpt 1). Additionally, she described how these roles are interconnected: “But if I had to choose, I’d say this one (pointing to advisor) best captures the overall idea. And these ones here (pointing to teacher, mentor, and coach), they seem more like the detailed aspects.” (Excerpt 1). She envisions the advisor role as encompassing elements of teacher, mentor, and coach.

On the other hand, Emiko (LA2) mentioned she considers her role to be that of an advisor, teacher, and mentor, but not a coach. “I feel like I cover roles 1, 2, and 3. I think I’m doing those kinds of things. But I don’t feel like I’m really able to go as far as solving problems through dialogue, like in number 4.” (Excerpt 2). She further expressed her hesitation, stating, “But Idon’t think number 4 is that easy to do” (Excerpt 2).

Emiko’s perspectives suggest that she sees problem-solving through dialogue as challenging, whereas Reiko integrates coaching as part of advising. Despite these differences, both LAs recognize the need for multiple roles in advising sessions, though their views on the specific coaching role differ.

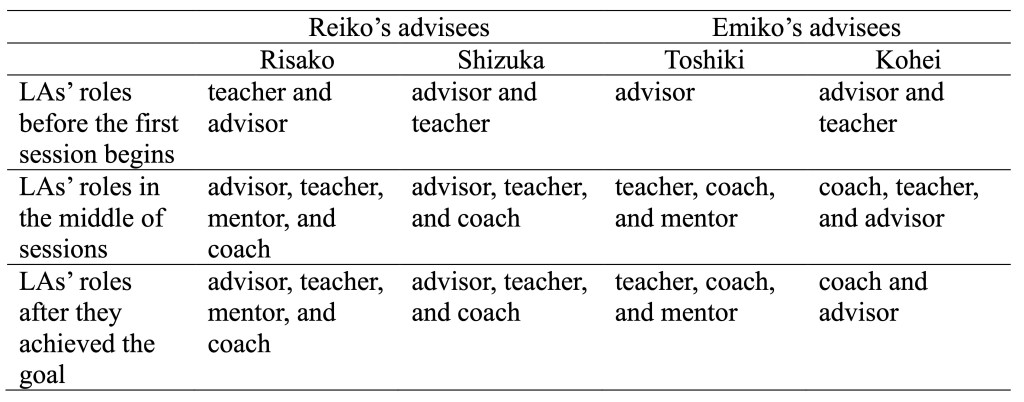

Answer to RQ2. What Are the Beliefs and Perspectives of Advisees Toward LAs’Roles?

Regarding the advisees’ perceptions of LAs’ roles in the online questions, advisees initially shared a similar understanding of LAs’ roles at the beginning, which is an advisor or a teacher. Over time, though, their perceptions evolved, leading to a shift in how they viewed the role of LAs as a mentor or a coach on top of an advisor and a mentor. Table 5 outlines the perceptions that advisees have regarding the LAs’ roles.

Table 5

How Advisees See LAs’ Roles

The first author asked three questions online as follows;

Q1: Which of the following (advisor, teacher, mentor, coach) is closest to the role of LA that you expected before the start of your first advising session? Please refer to the definition of roles. (Multiple choices allowed) Why?

Q2: Which of the following (advisor, teacher, mentor, coach) did you find the role of the language advisor to be similar to as you went through the sessions? Please refer to the definition of roles. (Multiple choices allowed) Why?

Q3: After achieving your goals, which of the following (advisor, teacher, mentor, coach) do you find the role of language advisor is like? Please refer to the definition of roles. (Multiple choices allowed) Why?

For Q1, before or at the beginning of the session, all advisees initially perceived LAs as advisors and/or teachers. Their reasons reflected expectations of cognitive support, such as strategies and skills (Excerpt 3). Risako wrote, “I thought that LAs would help me with a wide range of concerns, from basic information about the IELTS and TOEIC to how to take them and suggestions on specific test-taking strategies.” Shizuka expected guidance on the Pearson Benchmark test,[1] believing LAs had superior strategy knowledge. Toshiki wrote as reasons, “I just assumed they would provide expert advice and learning strategies specifically for English language study.” Kohei wrote, “I was able to learn basic knowledge about English as well as useful grammar for IELTS speaking and writing.”

Regarding Q2, once they became accustomed to the sessions, their perspectives evolved and expanded their perception of LAs to include mentor or coach roles on top of advisor or teacher roles (Excerpt 4). Risako noted that LA Reiko grasped her level and target score and suggestions. Shizuka wrote, “LA Reiko pointed out my strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement, and clearly explained what I needed to do to improve.” Toshiki highlighted LA Emiko’s advising methods; she asked questions such as ‘What do YOU want to do?’ and let advisees find out based on their will. Kohei wrote, “I came to see the LA Emiko more strongly as a coach. When I shared my goals—such as studying abroad, passing the Benchmark Test, or achieving a target IELTS score—she provided tailored study support to help me reach those goals. During our sessions, she also identified my weaknesses, such as grammar and speaking, and gave me clear, practical advice on how to improve.”

As for Q3, after achieving their goals, they selected coach and mentor roles, just as they did in Q2 (Excerpt 5). Risako wrote, “LA Reiko never responded negatively to my goals, which made me feel motivated to keep trying.” Toshiki wrote, “LA Emiko also encouraged me to look ahead by helping me assess my current situation and engaging in thoughtful dialogue. Through these dialogues, I received new knowledge and insights from her experiences, and in the end, I was always encouraged to make my own decisions.” Kohei wrote, “LA Emiko cooperated in setting the next goal based on the results.” However, Shizuka did not choose ‘mentor,’ as she viewed the sessions as a practice test experience and did not focus on personal awareness.

Answer to RQ3. Are There Any Incongruencies Between LAs’ and Advisees’ Beliefs and Perspectives About the Role of LAs?

Both LAs and advisees recognize that LAs fulfill multiple roles. Initially, advisees expect cognitive support similar to teachers or advisors, but over time, they perceive mentor and coach roles as well. Toshiki and Kohei noted that LA Emiko played the role of coach, but LA Emiko found the coaching role challenging and did not adopt it. LA Reiko believed she played all roles, which Risako agreed with. However, Shizuka did not acknowledge the mentor role, focusing solely on improving her Pearson Benchmark test score without awareness of other aspects.

Other Findings—Growing Autonomy

Consistent with other findings, it was observed that advisees became more self-directed throughout the continuous advising sessions in the advisees’ interviews. They began to perceive the roles of LAs as mentors or coaches in addition to advisors or teachers. For instance, Risako mentioned that she did everything that LA Reiko told her to do, which helped her decide to study TOEIC on her own. She thought she could apply the study methods that she learned through the IELTS study to the TOEIC study (lines 34-36 in the second interview in Excerpt 6). Toshiki said, “During spring break, I was able to make study plans on my own” (line 32 in the first interview in Excerpt 6). Kohei wrote, “LA Emiko cooperated in setting the next goal based on the results” (Answer to Online Question 3 in Excerpt 6). Thus, advisees became aware of their self-centered tendencies and made their own decisions as autonomous learners, as described by Little (1991).

Discussion

The analysis of all interviews and Online Questions revealed both LAs’ and advisees’ beliefs and perspectives regarding the role of LAs. Both the LAs and the advisees acknowledged the LAs’ multiple roles. While the advisees initially expected them to act as advisors or teachers, they later came to see the LAs as mentors or coaches as well. Furthermore, the findings highlighted a connection between the advisees’ autonomy and their perceptions of LAs’ roles. Rather than strictly distinguishing between the roles of advisor, teacher, mentor, and coach, the findings suggest that support should be adjusted based on the advisee’s status—shifting from advising to coaching as needed to foster greater autonomy.

As Riley (1997) emphasizes, it is crucial to clarify role distinctions and expectations in the advising relationship. Furthermore, Morrison and Navarro (2012) highlight the importance of transitioning from LTs to LAs. However, when applying Thompson’s Coaching Impact Model to an advising scenario, the role of a teacher would be part of a continuum leading toward mentoring and coaching. In this study, by incorporating advisees’ perspectives on the role of LAs, it was found that all four advisees initially viewed LAs as either advisors or teachers and primarily sought cognitive support (Online Question 1). For instance, in lines 34–36 of the second interview in Excerpt 6, Risako expressed that, thanks to the guidance and encouragement she received from LA Reiko, she was able to apply her learnings to a new area of study independently. Without Reiko’s cognitive and affective support in her role as a teacher, Risako felt she would not have gained the confidence to take control of her own learning. This suggests that adopting a teaching role is not necessarily negative for advisees, contrary to the concerns about power dynamics in teacher-student relationships mentioned by Kato and Mynard (2022).

However, in their responses to Online Question 2 in Excerpt 3 and Question 3 in Excerpt 4, Toshiki and Kohei began to view Emiko more as a mentor or coach, although they initially viewed her as a teacher or advisor. This shift in perception occurred because Emiko posed questions related to decision-making, prompting them to take a more active role in the process. As a result, they saw her as a coach rather than just a teacher.

These comments of Risako, Toshiki, and Kohei suggest that LAs do not necessarily need to avoid the teacher role from the advisees’ perspective. Instead, it is more important for LAs to flexibly adapt their roles based on the advisees’ needs and situations.

Conclusion

This paper explores the contentious issues surrounding LAs’ roles, exploring the beliefs and perspectives of both LAs and advisees at a university through qualitative research. The findings reveal that LAs at the university perceive themselves in diverse roles. In contrast, advisees initially view LAs as teachers/advisors, evolving to regard them as mentors/coaches over time. The research also highlights that these roles adopted by LAs are influenced by the specific needs of advisees. Throughout the interviews, most advisees expressed awareness of their transformation into autonomous learners. Consequently, the author contends that the key to ALL lies in LAs possessing the ability to flexibly adapt their roles based on the advisee’s context and needs.

Certain limitations need to be acknowledged. Firstly, regarding the selection of the participants, it would have been beneficial to interview not only advisees who continued attending advising sessions but also those who discontinued participation. This approach would have provided insights into how both groups perceived the LAs’ roles in their sessions. Additionally, focusing on one university with few participants limits generalizability. Expanding research to other institutions may enhance understanding and reveal additional roles of LAs in different contexts.

Despite its acknowledged limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the genuine benefits of understanding the roles of LAs. As Mozzon-McPherson (2007) and Kato and Mynard (2016) outlined, the key distinction between teachers and LAs lies in whether their work takes place within or outside the curriculum. However, LTs should also foster students’ autonomy within a classroom. Ideally, in the future, LAs and LTs will collaborate to cultivate autonomous learners both inside and beyond the classroom.

Data Availability Statement

The original for Excerpts 1-6 is available in IRIS at the following URL: https://doi.org/10.48316/chwBK-1sUPH

Notes on Contributors

Misato Saunders (ORCID: 0009-0009-1644-1277) is a full-time lecturer at the Center for Language Education at Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University, Japan. She is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in the Graduate School of Foreign Language Education and Research at Kansai University, Japan. Her doctoral research focuses on the well-being of Japanese teachers of English.

Osamu Takeuchi, Ph.D. (ORCID: 0000-0002-5195-992X) is a Professor at the Faculty of Foreign Language Studies and the Graduate School of Foreign Language Education and Research, Kansai University, Japan. His current research interests include language learning strategies, self-regulation in L2 learning, L2 learning motivation, and the application of technology to language teaching.

References

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. Pearson Longman.

Benson, P., & Lamb, T. (2021). Autonomy in the age of multilingualism. In M. Jiménez Raya & F. Vieira (Eds.), Autonomy in language education. (pp. 74–88). Routledge.

Carson, L., & Mynard, J. (2012). Introduction. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 3–25). Pearson.

Charmaz, K. (2020). Gurandeddo seorī no kōchiku: Dainihan. [Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.)]. (D. Okabe, Trans.; 2nd ed.). Nakanishiya. (Original work published 2014)

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. W. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge.

Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy in foreign language learning. Council of Europe.

Ito, M. (2017). Zukai kōchingu manējimento [Illustrated coaching management]. Discover 21.

Jupp, V. (2006). The Sage dictionary of social research methods. SAGE Publications.

Kato, S. (2012). Professional development for learning advisors: Facilitating the intentional reflective dialogue. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(1), 74–92. https://doi.org/10.37237/030106

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge.

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2022). Rifurecutibu daiarōgu: Gakushūsha ōtonomī wo hagukumu gengogakushū adobaijingu [Reflective dialogue: Language learning advising that fosters learner autonomy]. Osaka University Press.

Kelly, R. (1996). Language counselling for learner autonomy: The skilled helper in self-access language learning. In R. Pemberton, E. S. L. Li, W. W. F. Or, & H. D. Pierson (Eds.), Taking control: Autonomy in language learning (pp. 93–113). Hong Kong University Press.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE Publications.

Little, D. (1991). Learner autonomy 1: Definitions, issues and problems. Authentik.

Little, D. (1999). Learner autonomy is more than a Western cultural construct. In S. Cotterall, & D. Crabbe (Eds.), Learner autonomy in language learning: Defining the field and effecting change (pp. 11–18). Peter Lang.

Moriya, R. (2018). Exploring the dual role of advisors in English learning advisory sessions. Learner Development Journal, 1(2), 41–61. https://www.academia.edu/39749197/ Exploring_the_Dual_Role_of_Advisors_in_English_Learning_Advisory_Sessions

Morrison, B. R., & Navarro, D. (2012). Shifting roles: From language teachers to learning advisors. System, 40(3), 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2012.07.004

Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2007). Supporting independent learning environments: An analysis of structures and roles of language learning advisers. System, 35(1), 66–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2006.10.008

Otani, T. (2022). Shitsutekikenkyū no kangaekata: Kenkyūhōhōkara SCAT niyoru bunsekimade [Approaches to qualitative research: From research methods to analysis using SCAT]. Nagoya University Press.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Riley, P. (1997). The guru and the conjurer: Aspects of counselling for self-access. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 114–131). Longman.

Thompson, G. (2017). The master coach: Leading with character, building connections, and engaging in extraordinary conversations. SelectBooks.

van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. University of Western Ontario.

[1] The Pearson Benchmark Test is used in the English program as a proficiency test to assess students’ four skills—reading, listening, speaking, and writing—as well as their vocabulary and grammar. Students must achieve a certain score to receive a grade, which is part of the assessment in the English course.