Abd. Rahman, Institut Agama Islam Negeri Sorong, Southwest Papua, Indonesia. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0946-5325

Ahmad Mustamir Waris, Institut Agama Islam Negeri Manado, North Sulawesi, Indonesia. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8954-743X

Rahman, A., & Waris, A. M. (2025). From ‘mother of the house’ to ‘a housewife’: A narrative inquiry of a successful informal English language learner. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(2), 297–319. https://doi.org/10.37237/160203

Abstract

Informal language learning settings are important for second and foreign language development. While current literature has shown the benefits of informal context, especially for English language learning, ranging from its cognitive to social benefits, there is little inquiry into the fund of knowledge in the personal story of a successful EFL learner. Anchored in Zhang’s (2022) stages of language learning development: pre-production, early production, and communicative development, and Benson’s (2011a) and Rahman’s (2023) dimensions of informal language learning—location, formality, pedagogy, locus of control, and sociality—the study employs a narrative inquiry approach to analyze the participant journey. Findings reveal that the participant’s progression from passive observation to active communication underscores the importance of location, autonomy, and sociality in fostering linguistic competence. Her informal English learning experiences are sociocultural processes that show complex engagement among her learning agency and motivation, and communities with their varied sociocultural practices. The study contributes to the theoretical understanding of informal language learning by integrating sociality as an emerging dimension and offers practical insights for leveraging informal settings to enhance language learning.

Keywords: Informal learning; EFL; learning development; narrative inquiry

The topic of informal language learning, particularly learning that occurs outside of formal classroom contexts, has piqued the interest of language scholars and researchers in recent years (Benson, 2011a; Chik, 2019; Dressman & Sadler, 2020; Liu et al., 2024; Nunan & Richards, 2015; Reinders et al., 2022; Yang, 2020). A growing body of research suggests a positive correlation between learners’ engagement in diverse informal English language contexts and their language learning success (Hsieh & Hsieh, 2019; Kocatepe, 2017; Lai et al., 2015; Mideros, 2020). Reinders (2020) acknowledges that for many teachers and language researchers, language learning opportunities in informal settings become an ideal lacuna for language learners to improve their language skills, especially when formal classroom activities are less effective or limited. Although the literature has started to recognize the importance of informal learning contexts for the learner’s English development, we still don’t know much about the learning process in this informal context (Nguyen et al., 2024; Sadler, 2020). Nunan & Richards (2015) argue that traditionally, research, theory, and practice in language teaching have focused on the formal language classroom, investigating how the classroom environment, teachers, learners, and educational resources can create optimal learning conditions. Consequently, there has been a focus on developing methods and materials, designing syllabuses, and training teachers to effectively utilize the classroom setting as a source of meaningful input and genuine language use. Reinders (2020) states that only after the emergence of the social turn in language education research (Block, 2003) did language education scholars start paying major attention to learners’ personal, social, and contextual experiences, especially in informal settings. Therefore, there has been a growing emphasis on studying learners’ informal language learning experiences outside the classroom (Kashiwa & Benson, 2017; Rahman, 2023).

Analyzing ten top-ranked journals in the field of language education, Reinders (2020) found that only 5 percent of the articles explored the nuance of informal language learning beyond the classroom. While this small portion of informal language studies has given us some picture of informal language learning, many aspects of learners’ motivation, feelings, beliefs, and personal issues during informal language learning remain unclear. Rahman et al. (2024) argue that there are limited studies that explore an individual’s in-depth story of their experience with informal language learning beyond the classroom (Chik, 2019; Zhang, 2022). Therefore, to fill these foci, anchored on Zhang’s (2022) stages of language learning and Reinders and Benson’s (2017) dimension of informal language learning, this study examines the informal language learning experiences of a female English learner in the three stages, namely pre-production, early production and communicative development through five dimensions of informal language learning, namely: location, formality, pedagogy, locus of control and sociality (Rahman, 2023).

Literature Review

Informal Language Learning

Informal language learning occurs in non-academic environments, typically unplanned and lacking a formal structure (Benson, 2011a; Reinders et al., 2022; Sadler, 2020). Learning can occur through social interaction, media such as films, music, the internet, and everyday life experiences (Mideros, 2020; Rothoni, 2018). Informal language learning enables individuals to acquire knowledge in a more pertinent setting and is closely connected to their needs and interests (Kocatepe, 2017). Due to its enhanced flexibility, this learning context can effectively accommodate various learning styles and frequently enhances the desire for learning (Lai et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2024). Relying solely on classroom instruction is unlikely to enable English learners to achieve sufficient language proficiency, particularly in communicative contexts (Benson, 2011b; Chik, 2015; Dressman & Sadler, 2020; Reinders et al., 2022). Certain aspects of informal language learning, including authenticity, natural environments, language exposure, and learning support, have been identified as significant factors contributing to language learning success (Lee, 2021; Rahman et al., 2024; Rothoni, 2017).

Moreover, the significance of informal language learning contexts in English language acquisition has grown considerably with recent technological advancements, fundamentally transforming the landscape of English learning (Benson, 2021; Liu et al., 2024; Richards, 2015). Traditionally, English instruction took place in classrooms, where learners adhered to teacher-guided curricula. However, technological advancement has broadened learning possibilities, offering diverse and dynamic opportunities for language acquisition beyond formal settings (Peng et al., 2022). Kessler et al. (2023) highlighted that the surge in informal language learning research has been partly driven by the ongoing advancements in digital technologies, including the proliferation of applications, software, and electronic tools specifically designed to support language learning. Besides, many authentic applications and tools, such as YouTube channels and AI chat GPT, have provided opportunities for language socialization and practices accessible for language learners worldwide (Liu et al., 2024). Furthermore, migration and traveling have played a pivotal role in driving the expansion of research into informal language learning (Dressman & Sadler, 2020; Hajar, 2018; Zhang, 2022). Benson (2021) stated that when individuals increasingly engage in cross-border mobility for work, education, or leisure, they are often exposed to authentic linguistic and cultural environments that accelerate language acquisition outside formal settings. Migration, in particular, creates scenarios where language learning is essential for integration and daily survival, fostering interest in how informal contexts facilitate linguistic adaptation (Aldukhayel, 2023). Similarly, travel and immersion offer opportunities for experiential learning, where exposure to native speakers and real-life interactions enhances communicative competence (Lee & Jeong, 2013; Perry & Moses, 2019; Roskvist et al., 2014). Sadler (2020) suggests that a high percentage of traveling, mobility movement and high migration allows people to encounter the language informally in an authentic and natural setting, which was hardly found in the past. One study from Kunitz (2022) provides valuable insights into the contribution of migration in informal language contexts. The study highlights how real-life communication scenarios in migration contexts facilitate the interplay between linguistic resources and cultural competence, demonstrating that language learning extends beyond formal instruction.

Dimensions of Informal Language Learning.

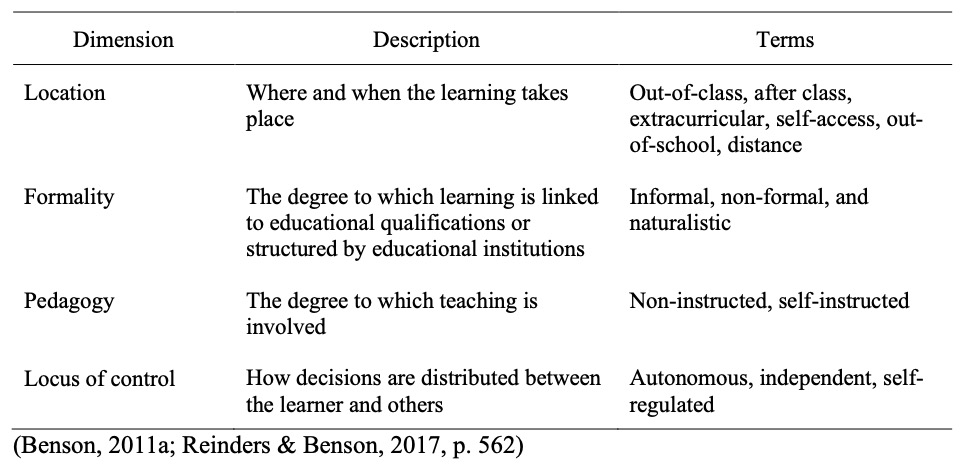

Benson (2011a) and Reinders and Benson (2017) outline a comprehensive framework for informal language learning outside the formal classroom, categorizing it into four key dimensions: location, formality, pedagogy, and locus of control.

Table 1

Dimensions of Informal Language Learning

Location is a defining characteristic of informal language learning, encompassing to physical and virtual spaces where learning occurs (Benson, 2021). For example, student accommodations serve as significant locations where learners gain meaningful exposure to the target language through interactions with roommates (Pearson, 2004). Kocatepe (2017) highlighted that houses are effective for language learning, especially when parents, siblings, and other family members act as language-learning peers and supporters (Palfreyman, 2011). The rapid advancement of technology has also expanded informal language learning into virtual spaces, providing learners with unprecedented access to language resources. These include social networking sites (Yang, 2020), language learning software (Chik, 2019), and artificial intelligence (Liu et al., 2024). Moreover, formality refers to the classification of learning based on its degree, encompassing formal, non-formal, and informal learning. Reinders and Benson (2017) conceptualize informality into intentional and incidental learning. Many English learners might have the intention of doing some informal language learning activities such as listening to English songs, watching English movies without subtitles, or using some English language software to improve their English during their free time (Chik, 2014; Rahman & Suharmoko, 2017). Some informal English learning activities might also occur without the awareness of the learners themselves, as these experiences are often embedded in routine social interactions or cultural practices, making the learning process implicit rather than explicit (Dizon, 2021; Lee, 2021; Li & Bonk, 2023).

Pedagogy dimension refers to the process of designing and implementing sequences of lessons that involve explicit and structured explanations, as well as evaluation methods. Chik (2019) accentuates this dimension into self-instructed learning and naturalistic learning in contrast with instructed learning (Benson, 2011b). Much informal language learning research on the pedagogical dimension advocates the integration of informal learning tools into formal instructional frameworks to maximize their pedagogical impact on language acquisition (Dizon, 2021; Kashiwa & Benson, 2017). The fourth dimension is the locus of control, which refers to control of the learning, such as other-directed, self-directed, independent, and autonomous learning, to who makes the major decision of learning (Benson, 2011a). The degree of control significantly shapes learners’ engagement and their capacity for lifelong learning (Reinders, 2020). Hyland (2004) and Lai et al. (2018) argue that self-directed and autonomous learners often exhibit greater responsibility in selecting learning strategies, setting goals, and seeking opportunities for practice (Nguyen et al., 2024).

In addition, the current literature on informal language learning has increasingly highlighted dimensions that extend and enrich Benson’s (2011a) framework, offering nuanced insights into the multifaceted nature of this process. For example, Rahman (2023) proposes the concept of sociality, which refers to the role of community and social networking in shaping the nature of informal language learning (Reinders & Benson, 2017). It shows that key social actors such as teachers, peers, parents, and other family members significantly influence learners’ engagement with informal English language learning. These actors not only affect learners’ motivation and attitudes but also determine the amount of time allocated to such learning and the specific types of informal language learning activities they undertake. Therefore, this study adds sociality as an emerging dimension alongside location, formality, pedagogy, and locus of control to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complexity of this multifaceted issue (Rahman, 2023; Reinders & Benson, 2017).

Methods

Narrative Inquiry

This study employed a qualitative narrative inquiry approach to describe the experiences and actions of language learning (Polkinghorne, 1995). In applied linguistics and second language acquisition (SLA), narrative inquiry is commonly used to explore the histories and experiences of language learners as they acquire a new language (Hajar, 2018). In this research, the stories of a thriving informal language learner were collected and analyzed thematically. The researcher formulated some narrative questions to guide the participant in reviewing and reporting her informal English language experiences that involve both cognitive and social processes of knowledge generation (Barkhuizen, 2013). The use of narrative inquiry as a research approach in language teaching and learning has been well established in prior studies to offer a valuable lens for examining various aspects of language learning, such as identity, gender, and age, providing rich and detailed data, particularly regarding the identities of language learners (Hajar, 2018; Pavlenko, 2007; Zhang, 2022). Narrative data, including journal writing, oral and written narratives, diaries, and interviews, were used to capture language learning processes outside formal educational environments (Kocatepe, 2017; Rahman et al., 2024). These data sources effectively capture the emotional, behavioral, and social dimensions of informal language learning.

The Participant and the Context

The participant in this study is Baya (pseudonym), a 33-year-old female who works as a university lecturer in Indonesia. Baya originally came from South Sulawesi Province and later migrated to Southwest Papua for work. Her first exposure to English occurred during formal education in Indonesia, but it was minimal. Her English language learning intensified during her stay in Australia, where she lived for over five years to accompany her husband while he was studying. Living in an English-speaking environment provided her with abundant opportunities to improve her English proficiency, primarily through informal settings. Baya reported that she frequently learned English by interacting with native speakers and other English users in Australia. Although she attended some formal English courses during her time there, she dropped out of the programs, expressing dissatisfaction with learning English in formal settings. Baya exemplifies a successful language learner since she achieved a high score on some English tests such as IELTS, a requirement for admission, and completing her master’s degree in accounting. Furthermore, she is regarded as a fluent English speaker as she has presented papers in English at numerous international seminars and workshops. Baya also worked at two different companies in Australia, both of which required high English proficiency, especially in spoken communication. Her extensive experience with informal language learning makes her a suitable subject for this study, which aims to explore the success story of English language learners in informal settings.

Data Collection and Analysis

Baya’s narratives were collected over a period of four months from August to December 2024, during which the researcher conducted four personal interviews, each lasting approximately 1–2 hours. In the subsequent four interviews, the researcher explored Baya’s informal English learning experiences in an English-speaking country, Australia. All four interviews were conducted in Baya’s first language, Indonesian, at her request. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and translated into English for analysis. To ensure accuracy, the translated data were reviewed by a professional Indonesian-English translator. The data was analyzed thematically, following the narrative construction framework by Zhang (2022) in which the study recorded Baya’s informal learning experiences through three levels of language acquisition: the pre-production, early production, and communicative development stage (see Krashen, 1982; Zhang, 2022). To provide a deeper analysis, the data were also coded based on Benson’s (2017) and Rahman’s (2023) five dimensions of informal language learning: location, formality, pedagogy, locus of control, and sociality.

Findings

Baya’s experiences with informal language learning were categorized into three stages: pre-production (the silent period), early production, and communicative development (see Krashen, 1982; Zhang, 2022).

The Pre-Production Stage

In the pre-production stage, Baya was immersed in an English-speaking environment but restricted herself to verbal communication. Instead, she concentrated on developing her receptive skills, especially listening, by absorbing the language through exposure and understanding. Baya engaged in various informal English learning activities, such as listening to English songs and watching English movies and news on TV that do not require her to speak directly. Baya described:

“During the first few months in Australia, I could not talk at all. Sometimes when I had to go to the supermarket alone, I would prepare some big money and give it to the teller without talking because I couldn’t understand the amount of money they mentioned, especially when they spoke faster. I kept saying, ‘Sorry, no English’.”

During this stage, the participant learns the vocabulary structure, sound pronunciation, and English grammar. She kept taking notes on some familiar expressions that frequently occurred during the conversation, such as “Hi, how are you mate?”, “Need a bag?” and “Have a flybuys card?”. The repeated exposures to the same expression and vocabulary allowed her to recognize some sentence patterns and build the vocabulary connection in the process of producing sentences that are critical in developing her communication skills. Baya’s motivation to learn English during this period stemmed mainly from her desire to understand English conversations during his daily routines, such as shopping for groceries and using public transportation. Baya was also driven by her intention to work part-time. She shared an unsuccessful job interview in which her low English communication skills led to rejection, motivating her to improve. She depicted:

“In my first job interview, the manager asked, what do you do? and answered in my basic Indonesian translation, “Mother of the house.” (saya seorang Ibu rumah tangga). The manager was confused, and I did not get the job.” My husband was laughing, and he said the answer should be “I am a housewife.”

Learning from her initial experience with the manager, Baya pushed herself to engage in many natural English communication contexts, such as visiting some cafes in the morning while listening to natural English conversations, going to grocery stores and visiting some public parks, and utilizing technological tools like YouTube videos and Google Translator to improve her English. Technology has become a supporting mechanism that is very important at this stage, offering unlimited resources to facilitate vocabulary development without pressure to initiate conversation directly. For example, Baya explained that she used Google Translate to translate phrases and sentences to order some food and showed them to the cafe staff. Thus, technology enables her to access contextual meaning and rich language scenarios to use in real-life communication. She stated, “If I don’t understand some words, I just find the translation in Google Translate or ChatGPT. Baya stated that technology assisted her in preparing for real-life communication by giving her a sample of vocabulary, phrases, and sentences that are generally used in certain types of communication. Before she participated in real conversation, she kept practicing using English in various contexts to anticipate some English conversations in the future.

Baya’s initial stage of English learning was marked by her focus on receptive skills over verbal language production. By immersing herself in listening activities such as watching movies, observing conversations, and leveraging technological tools like Google Translate and ChatGPT, she established a robust mental framework for language acquisition. This foundation enabled her to identify patterns, expand her vocabulary, and comprehend contextual meanings. Her intrinsic motivation, primarily fueled by her aspirations to socialize and for employment, drove her to engage with real-world language settings passively. At this stage, technology was pivotal, offering a low-pressure environment where she could develop her comprehension skills. Gradually, by exposing herself to English-speaking contexts such as markets and cafes, Baya transitioned from passive learning to active participation, ultimately navigating daily interactions with increased proficiency.

Early Production Stage

Baya narrated that after experiencing a silent period (Krashen, 1982) of over 2-3 months and engaging in critical interactions with English speakers in contexts such as markets and public transportation, she began to comprehend conversations. Although she continued to encounter challenges with vocabulary and understanding slang commonly used by English speakers, she initiated efforts to communicate. She began to understand most of the conversations in her surroundings. During this stage, she not only focused on understanding conversations but also actively initiated and participated in them. She recalled:

“There were moments when I needed to go to the market without my husband, who usually helped me communicate. During those times, I started using English—for instance, asking for prices or directions from bus drivers. I wasn’t always sure if my pronunciation was correct, but I tried to use simple words I had memorized. Sometimes they didn’t understand me, so I used body language or Google Translator.”

At this stage, Baya shifted her focus from vocabulary acquisition to communication. She maximized every opportunity to practice speaking and adopted an active approach to improving her skills by seeking interactions with English speakers, particularly Australian speakers. Her informal social interactions proved invaluable, providing her with real-world practice and cultural insights (Ramezanzadeh & Rezaei, 2019). Baya effectively takes the benefits of her environment by transforming it into a supportive and immersive learning context. Her approach aligns with Rahman’s (2023) argument that successful language learners leverage their environment by immersing themselves in language-rich contexts and negotiating social interactions to practice their skills.

Nevertheless, the shift from passive to productive English language users resulted in some obstacles, including nervousness and fear of making mistakes, vocabulary issues, and grammar mistakes, especially when she had spontaneous communication. Baya admitted to these challenges, especially when having conversations with her Indonesian community. To address this, she sought environments with fewer speakers from her native language background. She explained:

“I was happier to speak English with Australian friends or other English speakers than with my Indonesian friends and community. When speaking with native speakers, there’s no comparison—I didn’t feel the pressure to match their proficiency, as I sometimes did with Indonesian friends. I realized that other English speakers, especially Australians, were more permissive with errors and mistakes, encouraging me to practice and use my English despite its limitations.”

Baya’s journey from a silent learner to an active participant in English conversations highlights the critical role of immersive and authentic learning environments (Lee & Jeong, 2013). By leveraging opportunities in her surroundings, particularly interactions with native speakers and informal social contexts, she built confidence and improved her speaking skills. Real-life conversations, voluntary work, and social interactions provided her with a supportive, low-pressure environment for practice without fear of judgment. While formal English programs did not meet her needs, Baya’s active engagement with her community allowed her to make significant progress. Her experience underscores the importance of focusing on communication rather than perfection, utilizing the environment as a learning resource, and embracing spontaneous dialogue as an effective strategy for English language learning success.

Communicative Development

In the third stage, Baya’s main motivation is to develop her spoken communication skills, especially in daily communication. She kept immersing herself in naturalistic conversations every time she had the chance, such as talking to people she met in the coffee shops or on the beach, calling some call centers and asking about their products and services, and working in places allowing her to interact with more people such as in aged care facilities. She explained:

“To improve my English, especially my speaking skills, I chose to work in some aged care facilities and caravan parks because those places provided opportunities to communicate directly with customers, especially the elderly. Most of them were pensioners who were happy to talk. I felt more comfortable communicating with senior people since they were more open and welcome to talk. Interacting with them and sharing experiences allowed me to use my English genuinely and exposed me to various English variations.”

Baya’s experience of improving her English through work in aged care and caravan parks aligns with the principles of naturalistic informal language learning, which emphasize the importance of authentic, meaningful interaction in language acquisition (Benson, 2011b). By engaging with elderly customers, Baya found a supportive environment for language practice. Older individuals often displayed patience and willingness to communicate, enabling her to apply her English skills naturally. This type of communication setting offers rich opportunities through consistent, genuine interaction for her English language development, especially her speaking skills.

Moreover, during this phase, Baya showed her self-confidence and intrinsic motivation to engage in English communication actively. Baya’s confidence in initiating and maintaining conversations in a variety of social situations, such as at work, in the marketplace, and in informal interactions, increases, indicating that she is moving from a passive learner to an independent and active participant in the English-speaking environment. Thus, it accentuates the growth of her agency in the learning process since she becomes aware of the significance of regular practice in real-life contexts (Murray, 2017). Driven by her English improvements, especially in spoken communication, Baya implements an active approach by seeking opportunities for interaction with many English speakers to improve her confidence and strengthen her language learning process. She shared:

“Previously, I was afraid of even trying to speak, but I have more confidence now to speak English with other people, such as at my workplace and in the market. I realized that if I practice more, my English skills will get better.

The informal setting of an English-speaking country like Australia supported Baya’s efforts to develop her communicative skills. Learning and using English in such contexts stimulated spontaneous language use, encouraging learners to navigate social exchanges, adapt to various dialects, and respond to diverse speech acts. Baya employed strategies such as mimicking, using body language and non-verbal cues to compensate for her linguistic limitations, and employing trial-and-error methods to adjust to the fluidity of natural conversations. Informal English contexts—whether in community spaces, workplaces, or social gatherings—naturally provide her sustained exposure that naturally improves her English language skills. During this third stage of language development, Baya also demonstrated significant cognitive involvement in the process of learning English. She engaged in complex processes such as internalization, hypothesis testing, and the mental mapping of new linguistic structures and vocabulary. She explained:

“While using and practicing new words or sentences, I was constantly thinking about how everything fits together—the grammar, vocabulary, and sounds. I always rehearsed what I heard and applied it in conversations. I often asked my friends or husband whether I pronounced words correctly.”

In conclusion, Baya’s journey through the stages of informal language learning—from pre-production to communicative development—demonstrates the critical role of informal, real-life experiences in language learning. By initially developing her receptive skills and leveraging technology to aid comprehension, Baya built a strong foundation in English without the pressure of immediate verbal production. As she transitioned to active communication, her focus shifted to practicing in informal settings where supportive social environments fostered her progress. Her motivation, driven by personal and professional goals, enabled her to engage with native speakers and gradually build confidence. This underscores the importance of authentic, low-pressure interactions and community involvement in enhancing communicative competence in learning languages.

Discussion

The analysis of Baya’s English language learning journey, divided into three stages—pre-production, early production, and communicative development—offers a rich and nuanced understanding of informal language acquisition. This study contributes to Benson’s (2011a) and Rahman’s (2023) frameworks of informal language learning, by examining the interplay of location, formality, pedagogy, locus of control, and sociality in shaping Baya’s experiences. Unlike large-scale quantitative surveys, this qualitative case study underscores the complexity and transformative potential of informal learning contexts.

A focus on receptive skills marks Baya’s pre-production stage (Hyland, 2004; Kocatepe, 2017; Lai et al., 2015; Rothoni, 2022), offering insights into the foundational aspects of informal language learning. Her informal interactions in various environments, such as at supermarkets, cafes, and Sunday markets, illustrate the critical role of location in providing authentic linguistic input (Schiller, 2021). These settings enabled her to observe and absorb conversational English in natural contexts. For example, Baya’s frequent visits to cafes allow her to listen to authentic conversations, facilitating her gradual understanding of linguistic norms and cultural nuances. Moreover, Baya’s engagement with technology enables her to expand her access to diverse linguistic and cultural resources, providing her with opportunities for meaningful English interaction with multiple locations such as through social media and other social networking sites (Benson, 2021). Moreover, the formality of these interactions further shaped her learning trajectory. Reinders et al. (2022) asserted that, unlike structured classroom environments, the informal nature of these settings encourages unscripted and contextually rich exchanges (Li & Bonk, 2023; Nguyen et al., 2024; Rahman et al., 2024). Baya’s reliance on non-verbal communication and tools such as YouTube videos highlights how informal environments foster situated learning (Chik, 2019). Sadler (2020) argued that by observing real-life interactions and practicing situational vocabulary, informal language learners can internalize pragmatic language use and benefit from the pedagogical richness of informal contexts.

Furthermore, Baya’s proactive engagement in learning activities underscores the significance of locus of control (Benson, 2021). Her decision to visit specific locations, use technological tools, and focus on receptive skills exemplify her autonomy in directing her learning process. This autonomy is a core tenet of Benson’s (2011a) framework, illustrating how learners take control of their own language development, especially in informal settings. The concept of sociality, as proposed by Rahman (2023), further enriches the analysis of Baya’s pre-production stage. Although she initially refrained from active participation, her observation of social interactions in cafes and markets reflects the relational dimension of language learning (Kocatepe, 2017; Palfreyman, 2011). Her focus on understanding conversational norms and social dynamics facilitated her gradual integration into the linguistic community, emphasizing the relational and communal aspects of learning.

In addition, in the early production stage, Baya transforms from a passive to an active language learner, portraying a pivotal phase in her learning process. The transformation also acknowledges the dynamic interplay of informal language learning dimensions, including location, pedagogy, formality, locus of control, and sociality (Rahman, 2023), particularly as Baya started to engage in authentic communication. The location remains a key enabler of language learning during this stage. Public spaces such as parks, beaches, and malls turn out to be a learning arena. This informal learning environment offers more chances for unplanned, authentic interactions to occur, facilitating Baya’s transition to being a productive language user (Lee, 2021; Perry & Moses, 2019). This aligns with the spatial aspect of language learning that shapes the language learners’ nature (Benson, 2021; Murray & Fujishima, 2013). Rahman (2023) acknowledges that the informality of these interactions offers a supportive, low-pressure environment for experimentation. Baya’s reflections on her experiences with friends and native speakers highlight the value of spontaneous and natural communication in reducing anxiety and fostering confidence. Reinders (2020) highlights that informal contexts facilitate adaptive learning experiences by allowing learners to navigate linguistic fluidity (Rothoni, 2018). From a pedagogical perspective, Baya’s strategic use of tools such as Google Translator and her deliberate efforts to initiate conversations illustrate the integration of intentional and incidental learning (Reinders & Benson, 2017). Her approach to practicing pronunciation and vocabulary in real-world scenarios underscores the experiential nature of informal learning, enabling her to internalize linguistic structures and develop pragmatic competence (Chik, 2019).

Moreover, the locus of control in this stage is evident in Baya’s proactive efforts to seek out English-speaking environments. Her decision to limit interactions with her Indonesian community and prioritize engagement with other English speakers reflects her agency in creating opportunities for language use (Hajar, 2018; Lantolf et al., 2018; Lantolf & Beckett, 2009). In Baya’s case, her conscious decision to shift from a dependency on familiar linguistic networks to spaces that necessitates the active use of English illustrates a nuanced understanding of how to navigate and exploit informal settings for linguistic gains. This transition highlights the interplay between autonomy and strategic engagement as the learner seeks out contexts that align with her linguistic goals and foster sustained opportunities for practice (Benson, 2011b; Choi & Nunan, 2018; Nunan & Richards, 2015). From a sociality perspective, Baya’s deliberate engagement with family, especially her husband, friends, and people in public spaces, highlights the importance of relational dynamics in fostering a supportive environment for language learning. The sociality dimension also highlights the interactive nature of social interaction in which Baya gains linguistic knowledge and is actively involved in the social dynamics of the interaction. By directly participating in conversations, posing questions, and requesting clarification, Baya engages in a co-constructed process of learning that strengthens her communicative skills and personal relationships. It depicts a collaborative approach to constructing meaning pivotal to sociality (Lantolf, 2000; Palfreyman, 2011). Additionally, the relational scaffolding provided by these interactions facilitates Baya’s gradual transition from passive observation to active participation (Lantolf et al., 2018).

Furthermore, the final stage of Baya’s learning journey, communicative development, demonstrates the cumulative impact of informal learning contexts on her communicative competence. Her deliberate engagement in real-world communicative practices characterizes this stage, offering a nuanced understanding of how informal environments facilitate advanced language development (Dressman & Sadler, 2020; Lee, 2021; Nunan & Richards, 2015; Rahman et al., 2024). Like the previous two stages, location still played a pivotal role in this stage, as Baya accessed diverse linguistic inputs through complex spatial nuances that involved interactions in aged care facilities, caravan parks, and public spaces (Benson, 2021; Murray, 2018). These settings expose her to variations in accents and colloquial expressions, enhancing her ability to adapt to real-world communicative demands. Her reflections on interacting with Australian elderly people and sharing their experiences underscore the importance of authentic, context-specific interactions in fostering advanced linguistic competence (Reinders et al., 2022).

Meanwhile, the informality of these interactions further highlights the value of natural communication. Dressman and Sadler (2020) accentuate that the ability to navigate spontaneous conversations and respond to unpredictable linguistic scenarios illustrates the adaptive and transformative potential of informal contexts (Nguyen et al., 2024; Rothoni, 2022). Moreover, the pedagogical dimension of Baya’s experiences reveals the implicit learning mechanisms embedded in informal interactions (Wilks-Smith & Thong, 2019; Yang, 2020). Lantolf & Beckett (2009) assert that by engaging with encouraging interlocutors or other more proficient language users, language learners create opportunities for scaffolded learning that facilitates the acquisition of complex linguistic features (Dongyu et al., 2013; Fahim & Haghani, 2012; Vygotsky, 1978). As Reinders and Benson (2017) state, through the pedagogical dimension, informal language learners merely integrate the liberating practice and incidental learning, such as Baya’s experimentation with new vocabulary and grammar in real-world scenarios.

Moreover, the locus of control in this stage is evident in Baya’s determination to overcome linguistic challenges and expand her communicative repertoire (Chik, 2019). Her strategic approach to seeking out conversational opportunities and taking the initiative to start dialogues underscores her agency in directing her language development (Chik, 2014; Murray, 2017; Reinders, 2020). Rahman (2023) states that strong control of learning is shown by learners’ active pursuit of or creating learning opportunities. This is manifested in Baya’s actions, such as instead of awaiting learning opportunities to come in the first stage, Baya intentionally sought out and initiated dialogues. This proactive behavior reflects her intrinsic motivation and illustrates her capacity to take ownership of her learning process (Fathali & Okada, 2016; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Nunan and Richards (2015) highlight that autonomy is essential for fostering linguistic competence, particularly in informal settings where structured support may be limited. Finally, the concept of sociality underscores the relational and communal aspects of Baya’s learning journey. Her growing social networking and interaction, such as from only family members to friends in the workplace and from the Indonesian community to other different national communities, set a critical component of her English language development (Palfreyman, 2011; Reinders et al., 2022). Expanding her social networking fosters deeper language interaction, allowing her to enrich her linguistic inputs and repertoire. Thus, it illustrates the interplay between linguistic competence and social integration (Benson, 2021; Rahman, 2023).

Conclusion

This study illuminates the complex interrelationship among location, pedagogy, formality, locus of control, and sociality across three informal language learning development stages. From the pre-production phase through early production to communicative development, the findings underscore the transformative potential of informal contexts in facilitating language acquisition. Drawing on Benson’s (2011a) theoretical frameworks, the study demonstrates how informal environments foster authentic engagement, scaffolded learning, and adaptive language use. Baya’s experiences exemplify the foundational role of location and social interaction in providing diverse linguistic input through various modes of formality and pedagogical approaches. The locus of control also proves essential, highlighting the value of learning agency in shaping the informal learning environment. The study enriches the growing body of literature on informal language learning by adding perspectives to the social complexities that shape language learning and acquisition. The findings reveal how learners can effectively leverage informal contexts to progress from passive observation to active language use and ultimately to advanced communicative competence. By incorporating sociality as a fifth dimension alongside the established concepts of informal language learning (location, formality, pedagogy, and locus of control) (Rahman, 2023), this study not only enriches existing theoretical frameworks but also presents practical implications for educators and learners seeking to harness the potential of informal settings for meaningful language learning.

Notes on the Contributors

Abd. Rahman is an Associate Professor in teaching and learning English as a foreign language at the Faculty of Education, IAIN Sorong, Southwest Papua, Indonesia. His research areas are informal language learning, learner autonomy, and community-based language learning.

Ahmad Mustamir Waris is a senior lecturer and researcher at the State Islamic Institute of Manado, North Sulawesi, Indonesia. He has been teaching English for over ten years, and his research areas are technology in language learning, curriculum development, and learner identity.

References

Aldukhayel, D. M. (2023). Factors influencing L2 maintenance in the L1 environment: A case study of an Arab returnee child. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 13(4), 965–974. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1304.18

Barkhuizen, G. (2013). Narrative research in applied linguistics. Cambridge University Press

Benson, P. (2011a). Language learning and teaching beyond the classroom: An introduction to the Field. In P. Benson & H. Reinders (Eds.), Beyond the language classroom (1st ed., pp. 7–16). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Benson, P. (2011b). Teaching and researching: Autonomy in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833767

Benson, P. (2021). Language learning environments: Spatial perspectives on SLA. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788924917

Block, D. (2003). The social turn in second language acquisition. Georgetown University Press.

Chik, A. (2014). Digital gaming and language learning: Autonomy and community. Language Learning and Technology, 18(2), 85–100. http://dx.doi.org/10125/44371

Chik, A. (2015). “I don’t know how to talk basketball before playing NBA 2K10”: Using digital games for out-of-class. In D. Nunan & J. C. Richards (Eds.), Language learning beyond the classroom (pp. 91–100). Routledge. https://doi. org/10.4324/9781315883472

Chik, A. (2019). Motivation and informal language learning. In M. Dressman & R. W. Sadler (Eds.), The handbook of informal language learning (1st ed., pp. 13–26). Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119472384.ch1

Choi, J., & Nunan, D. (2018). Language learning and activation in and beyond the classroom. Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1(2), 49–63. https://doi.org/10.29140/ajal.v1n2.34

Dizon, G. (2021). Subscription video streaming for informal foreign language learning: Japanese EFL students’ practices and perceptions. TESOL Journal, 12(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.566

Dongyu, Z., Fanyu, & Wanyi, D. (2013). Sociocultural theory applied to second language learning: Collaborative learning with reference to the Chinese context. International Education Studies, 6(9), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v6n9p165

Dressman, M., & Sadler, R. W. (2020). The handbook of informal language learning. Wiley-Blackwel. https://doi.org/10.1002%2F9781119472384

Fahim, M., & Haghani, M. (2012). Sociocultural perspectives on foreign language learning. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 3(4), 693–699. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.3.4.693-699

Fathali, S., & Okada, T. (2016). A self-determination theory approach to technology-enhanced out-of-class language learning intention: A case of Japanese EFL learners. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning, 6(4), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsll.2016.1607

Hajar, A. (2018). Motivated by visions: a tale of a rural learner of English. Language Learning Journal, 46(4), 415–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2016.1146914

Hsieh, H. C., & Hsieh, H. L. (2019). Undergraduates’ out-of-class learning: Exploring EFL students’ autonomous learning behaviors and their usage of resources. Education Sciences, 9(3), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9030159

Hyland, F. (2004). Learning autonomously: Contextualising out-of-class English language learning. Language Awareness, 13(3), 180–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410408667094

Kashiwa, M., & Benson, P. (2017). A road and a forest: Conceptions of in-class and out-of-class learning in the transition to study abroad. TESOL Quarterly, 52(4), 725–747. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.409

Kessler, M., Loewen, S., & Gönülal, T. (2023). Mobile-assisted language learning with Babbel and Duolingo: comparing L2 learning gains and user experience. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 38(4), 690–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2023.2215294

Kocatepe, M. (2017). Female Arab EFL students learning autonomously beyond the language classroom. English Language Teaching, 10(5), 104–126. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n5p104

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon Press Inc. https://doi.org/10.2307/328293

Kunitz, S. (2022). Enhancing language and culture learning in migration contexts. In H. Reinders, C. Lai, & P. Sundqvist (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language learning and teaching beyond the classroom (pp. 181–194). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003048169

Lai, C., Hu, X., & Lyu, B. (2018). Understanding the nature of learners’ out-of-class language learning experience with technology. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 31(1–2), 114–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1391293

Lai, C., Zhu, W., & Gong, G. (2015). Understanding the quality of out-of-class english learning. TESOL Quarterly, 49(2), 278–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.171

Lantolf, J. P. (2000). Socicultural theory and second language learning. Oxford University Press.

Lantolf, J. P., & Beckett, T. G. (2009). Sociocultural theory and second language acquisition. Language Teaching, 42(4), 459–475. https://doi:10.1017/S0261444809990048

Lantolf, J. P., Poehner, M. E., & Swain, M. (2018). The Routledge Handbook of Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Development. Routledge.

Lee, J. S. (2021). Informal digital learning of English: Research to practice (1st ed.). Routledge.

Lee, J. S., & Jeong, E. (2013). Korean-English dual language immersion: Perspectives of students, parents and teachers. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 26(1), 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2013.765890

Li, Z., & Bonk, C. J. (2023). Self-directed language learning with Duolingo in an out-of-class context. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 0(0), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2023.2206874

Liu, G. L., Darvin, R., & Ma, C. (2024). Exploring AI-mediated informal digital learning of English (AI-IDLE): a mixed-method investigation of Chinese EFL learners’ AI adoption and experiences. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 38(3), 569–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2024.2310288

Mideros, D. (2020). Out-of-class learning of Spanish during COVID-19: A case study in Trinidad and Tobago. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 11(3), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.37237/110308

Murray, G. (2017). Autonomy in the time of complexity : Lessons from beyond the classroom. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 116–134. https://doi.org/10.37237/080205

Murray, G. (2018). Self-access environments as self-enriching complex dynamic ecosocial systems. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 9(2), 102–115. https://doi.org/10.37237/090204

Murray, G., & Fujishima, N. (2013). Social language learning spaces: Affordances in a community of learners. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics (Quarterly), 36(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/cjal-2013-0009

Nguyen, H. A. T., Chik, A., Woodcock, S., & Ehrich, J. (2024). Language learning beyond the classrooms: Experiences of Vietnamese English major and non-English major students. System, 121(January), 103232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2024.103232

Nunan, D., & Richards, J. C. (2015). Language learning beyond the classroom. Routledge.

Palfreyman, D. M. (2011). Family, friends, and learning beyond the classroom: Social network and social capital in language learning. In P. Benson & H. Reinders (Eds.), Beyond the Language Classroom (1st ed., pp. 17–34). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230306790_3

Pavlenko, A. (2007). Autobiographic narratives as data in applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics, 28(2), 163–188.

Pearson, N. (2004). The idiosyncrasies of out-of-class language learning : A study of mainland Chinese students studying English at tertiary level in New Zealand. Proceedings of the Independent Learning Conference 2003, September, 1–12. http://independentlearning.org/ILA/ila03/ila03_pearson.pdf

Peng, H., Jager, S., & Lowie, W. (2022). A person-centred approach to L2 learners’ informal mobile language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(9), 2148–2169. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1868532

Perry, K. H., & Moses, A. M. (2019). Mobility, media, and multiplicity: Immigrants’ informal language learning via media. In The handbook of informal language learning (pp. 2015–2228). https://doi.org/10.1002%2F9781119472384

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 8(1), 5–23.

Rahman, A. (2023). Language learning beyond the classroom (LBC): A case study of secondary school English language learners in a rural Indonesian Pesantren [The University of South Australia]. https://find.library.unisa.edu.au/discovery/fulldisplay/alma9916820631601831/61USOUTHAUS_INST:ROR

Rahman, A., & Suharmoko. (2017). Building autonomous learners in English as a foreign language (EFL) classroom. Proceedings of the International Conference on Education in Muslim Society, 231–234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2991/icems-17.2018.44

Rahman, A., Syahrul, Siddik, H., Syalviana, E., & Suharmoko. (2024). Out-of-class language learning (OCLL): A case study of a visually-impaired EFL learner. World Journal of English Language, 14(5), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v14n5p283

Ramezanzadeh, A., & Rezaei, S. (2019). Reconceptualising authenticity in TESOL: A new space for diversity and inclusion. TESOL Quarterly, 53(3), 794–815. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.512

Reinders, H. (2020). A framework for learning beyond the classroom. In M. J. Raya & F. Vieira (Eds.), Autonomy in language education (pp. 63–73). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429261336-6

Reinders, H., & Benson, P. (2017). Research agenda: Language learning beyond the classroom. Language Teaching, 50(4), 561–578. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444817000192

Reinders, H., Lai, C., & Sundqvist, P. (Eds.). (2022). The Routledge handbook of language learning and teaching beyond the classroom. Routledge.https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003048169

Richards, J. C. (2015). The changing face of language learning: Learning beyond the classroom. RELC Journal, 46(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688214561621

Roskvist, A., Harvey, S., Corder, D., & Stacey, K. (2014). ‘To improve language, you have to mix’: teachers’ perceptions of language learning in an overseas immersion environment. Language Learning Journal, 42(3), 321–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2013.785582

Rothoni, A. (2017). The interplay of global forms of pop culture and media in teenagers’ ‘interest-driven’ everyday literacy practices with English in Greece. Linguistics and Education, 38, 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2017.03.001

Rothoni, A. (2018). The complex relationship between home and school literacy: A blurred boundary between formal and informal English literacy practices of Greek teenagers. TESOL Quarterly, 52(2), 331–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.402

Rothoni, A. (2022). Ethnography in LBC research. In H. Reinders, C. Lai, & P. Sundqvist (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language learning and teaching beyond the classroom (pp. 381–394). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003048169

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Sadler, R. W. (2020). Virtual landscapes. In R. W. Sadler & M. Dressman (Eds.), The handbook of informal language learning (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Schiller, A. (2021). Building Language Skills and Social Networks in an Advanced Conversation Club: English Practice in Lecce. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 12(1), 70–78. https://doi.org/10.37237/120105

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Wilks-Smith, N., & Thong, L. P. (2019). Transformative language use in and beyond the classroom with the voice story app. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 10(3), 282–295. https://doi.org/10.37237/100305

Yang, Y. (2020). EFL learners’ autonomous listening practice outside of the class. SiSAL Journal, 11(4), 328–346. https://doi.org/10.37237/110403

Zhang, Z. (2022). Learner engagement and language learning: a narrative inquiry of a successful language learner. Language Learning Journal, 50(3), 378–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2020.1786712