Pınar Üstündağ-Algin, School of Foreign Languages, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Ankara, Türkiye. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2595-6570

Üstündağ-Algin, P. (2025). Integrating social-emotional learning into L2 instruction in higher education: Effects on learner autonomy. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(4), 653–672. https://doi.org/10.37237/160404

Abstract

Learner autonomy is a key objective in higher education language programs. Social-emotional learning has been proposed as a pedagogical approach to support autonomy by addressing learners’ emotional and social competencies, notably self-awareness and social awareness. This mixed-methods, quasi-experimental pretest–posttest study in a university English preparatory program investigated the impact of embedding SEL activities into a seven-week course on learners’ autonomy development. The experimental group (n = 21) received SEL-infused instruction targeting self-awareness and social awareness, while the control group (n = 21) followed the same syllabus without SEL content. Learner autonomy was measured pre- and post-intervention using a learner autonomy scale, and qualitative data (weekly Padlet reflections and a final opinion paper) captured learners’ perceptions of the learning process. Quantitative results showed that the experimental group achieved greater gains in autonomy compared to the control group. Qualitative findings, analysed through Zimmerman’s self-regulated learning framework, revealed that SEL activities supported learners in setting personal goals, employing learning strategies, and collaborating with peers. These results underscore the pedagogical value of integrating SEL into L2 instruction to foster learner autonomy, highlighting that strengthening learners’ emotional and social skills can enhance their self-regulation and overall engagement in language classrooms.

Keywords: learner autonomy, social-emotional learning, self-awareness, social awareness, self-regulated learning, higher education, L2 education

“The only person who is educated is the one who has learned how to learn and change.” – Carl Rogers, 1969

In second-language (L2) education, two areas of growing emphasis are the promotion of learner autonomy (LA) and the incorporation of social-emotional learning (SEL) dimensions into teaching. LA is commonly positioned as a cornerstone of learner-centred pedagogy, foregrounding learners’ agency and responsibility for shaping how they learn. SEL, in turn, is typically defined as the development of competencies that help learners understand and manage emotions, build relationships, and make responsible decisions, most prominently organised around competencies such as self-awareness and social awareness (CASEL, 2025). Meta-analytic evidence from general education links SEL-oriented programmes with gains in learners’ engagement and achievement (Durlak et al., 2011), and work in L2 education has increasingly argued that SEL is relevant to L2 learning because L2 classrooms are inherently social, identity laden, and affectively demanding (Pentón Herrera, 2020).

Within higher education (HE) L2 contexts, examining the intersection between SEL and LA is timely and consequential, particularly because LA is enacted within social contexts and relationships (Little, 2007; Murray, 2014). From this perspective, LA is not the absence of others but a capacity often enabled through interdependence, including learners’ ability to collaborate, negotiate meaning, and engage productively with peers. Accordingly, learners who develop stronger self-awareness and social awareness might be better positioned to exercise autonomy in ways that are purposeful and sustainable in the L2 classroom and beyond. Against this backdrop, the present study explores how SEL-oriented practices, with a specific focus on self-awareness and social awareness, might foster LA in HE L2 instruction.

Learner Autonomy in Second-Language Education

Recent scholarship conceptualises LA in L2 education as a multidimensional, socially situated, and developmentally dynamic capacity. LA is increasingly understood as an emergent construct that is enacted and, at times, constrained through interaction among learners’ agency, tasks, tools, and institutional conditions, which makes conceptual clarity and operational precision especially important (Stringer, 2024). Empirical research also suggests that autonomy can be observed through self-regulated engagement in digital and hybrid environments. For example, autonomy-related differences appear in time management and pacing behaviours captured via learning analytics, even when learning gains do not always diverge neatly across learner profiles (Ko et al., 2024). Recent syntheses of technology-supported self-regulated language learning similarly indicate that digital tools can support autonomy-relevant processes such as planning, monitoring, and collaboration, while also underlining a persistent design tension. Autonomy tends to strengthen when choice is paired with structure, feedback loops, and social support rather than open-ended flexibility alone (Yu, 2023). Importantly, autonomy outcomes are not purely individual, since constraints and obstacles in L2 learning beyond the classroom, including environmental and social barriers, remain a salient part of how autonomy is experienced and sustained in real settings (Gardner et al., 2023). Taken together, these insights highlight the need for institutional structures that support LA across physical and digital spaces.

Methodologically, the question of how autonomy is measured remains central. LA research has historically foregrounded qualitative approaches that can capture autonomy as lived practice in context, including learners’ narratives, reflective accounts, and situated decision making. At the same time, recent syntheses argue that quantitative and mixed-method approaches are not conceptually misplaced, provided that researchers specify what exactly is being operationalised and triangulate evidence across indicators rather than treating any single score as autonomy itself (Chong & Reinders, 2022). In practice, this has meant combining validated self-report measures of autonomy-related beliefs and behaviours with behavioural traces (for example, pacing and time use indicators) and learning outcomes, particularly in technology-mediated environments (Ko et al., 2024; Nguyen & Habók, 2021).

Historically, the turn toward LA in L2 education informed practical infrastructures, most notably self-access learning and language centres, intended to extend autonomy support beyond classroom time and to provide material, social, and advisory resources for learner-directed work (Little, 2015). Contemporary equivalents of self-access are increasingly hybrid and distributed. Alongside physical self-access learning centres, LA is now mediated through online platforms, learning management systems, and curated digital resource ecosystems. Human support structures such as advising, consultations, and mentoring can also play a central role by strengthening relational support and sustaining reflective engagement that guides learners’ decisions about goals, strategies, and resources (Üstündağ Algın et al., 2022). Evidence from the pandemic period shows that synchronous online advising and consultations can remain autonomy supportive and motivationally viable, and learners report wanting such services to continue as a stable component of self-access provision (Andersson & Nakahashi, 2023; Güven Yalcin, 2021; Mynard et al., 2023). Recent observations from Europe likewise show that institutions operationalise self-access support through blended spaces, advising, learner development initiatives, and social learning opportunities (Mynard, 2024). Overall, the current trajectory is not away from self-access but toward reconfiguring self-access infrastructures to integrate learner choice with guidance, community-based support, and scalable digital provision (Little, 2015; Mynard, 2024). In this framing, LA is not reduced to individual independence but can flourish collectively within supportive self-access infrastructures that connect learners to people, practices, and possibilities (Murray, 2018; Mynard & Shelton Strong, 2022).

Social‑Emotional Learning

SEL is commonly defined as the development of competencies that help learners understand and manage emotions, build supportive relationships, and make responsible decisions (CASEL, 2025). A robust evidence base links SEL programmes with improved academic outcomes and reduced emotional distress, although effects can vary across cultural and institutional contexts, which underscores the importance of local adaptation (Chen & Yu, 2022; Taylor et al., 2017; Weissberg, 2019). In L2 education, SEL offers a complementary lens for understanding how learners sustain engagement, manage affective demands, and participate constructively in the social life of the classroom, especially in HE, where communication can be high stakes, and interaction is central to learning (Pentón Herrera, 2020). Recent work in HE L2 contexts further suggests that SEL-oriented activities can strengthen classroom climate and foster capacities such as emotion regulation, empathy, and teamwork, which are plausibly relevant to how LA is enacted and sustained through relationships and participation (Herasymenko & Muravska, 2024).

The CASEL Framework

Within the broader SEL landscape, the CASEL framework organises SEL around five broad and interrelated competency domains, namely self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision making (CASEL, 2025). The present study focuses on self-awareness and social awareness. CASEL defines self-awareness as the ability to understand one’s own emotions, thoughts, and values and how they influence behaviour across contexts, including recognising one’s strengths and limitations with a well-grounded sense of confidence and purpose. Social awareness, in turn, concerns the ability to understand others’ perspectives and empathise with individuals from diverse backgrounds, cultures, and contexts, including understanding broader historical and social norms for behaviour in different settings (CASEL, 2025). In an L2 setting, these competencies can be operationalised through reflective and interactional practices that support LA, including articulating goals aligned with learners’ identities, monitoring affect during communication, seeking feedback and support, and collaborating with peers in ways that sustain engagement and ownership.

Linking SEL and LA in Self-Access Settings

LA in HE L2 learning is understood as a capacity enacted through both self-regulation and socially mediated participation rather than as solitary independence (Murray, 2014). This makes a self-access learning context especially suitable for examining the SEL and LA link, because self-access provision is designed to extend autonomy support beyond classroom time by combining learner choice with guidance, peer interaction, and developmental resources, thereby creating an institutional ecology where autonomy can be exercised without being equated with isolation (Mynard, 2024). Within such ecologies, autonomy is more likely to strengthen when learners experience a supportive climate and have scaffolds that help them sustain purposeful engagement. From this perspective, SEL-oriented practices can be viewed as complementary supports for autonomy-oriented pedagogy. In particular, self-awareness can help learners identify goals, strengths, and affective responses to challenge, while social awareness can support help-seeking, collaborative learning, and constructive participation with peers, all of which can make autonomous engagement more durable and sustainable in practice (CASEL, 2025; Mahoney et al., 2021). These considerations motivate an empirical test of whether embedding SEL activities focused on self-awareness and social awareness in HE L2 instruction yields measurable gains in LA relative to a comparison condition without SEL.

RQ: How, and to what extent, does embedding SEL activities focused on self-awareness and social awareness in HE EFL courses foster learner autonomy, compared with a control condition without SEL?

Methodology

Context and Participants

This quasi-experimental study was conducted in the English preparatory school of a public university in Ankara, Türkiye. Learners enrolled in the preparatory programme must reach CEFR C1 proficiency across all four language skills to enter their degree programmes. Two intact B1 level classes were selected through convenience sampling, prioritising practical accessibility and voluntary participation (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2017; Patton, 2002). The experimental group (n = 21; 10 women, 11 men; age 18 to 20) followed a seven-week syllabus totalling 21 class hours that embedded the CASEL competencies of self-awareness and social awareness (CASEL, 2025) within the existing skill-based English curriculum. There were two reasons for focusing on these two CASEL competencies: (1) the brief duration of the intervention, and (2) the aim of enabling participants in the experimental group to deeply internalise self- and social awareness. The control group (n = 21; 11 women, 10 men; age 18 to 21) completed the same syllabus without explicit SEL content and served as the comparison condition.

Institutional ethics approval was obtained, and all participants provided written informed consent. Although optional and ungraded, all experimental participants completed weekly Padlet reflections and a final opinion paper, indicating strong engagement.

Research Design

An embedded mixed-methods, quasi-experimental pretest–posttest design was employed. The SEL-enriched instructional program served as the independent variable and targeted self-awareness and social awareness activities aligned with the CASEL framework. The dependent variable was LA, measured using the Learner Autonomy Scale (LAS; Orakcı & Gelişli, 2017). Quantitatively, the LAS was administered to both groups before and after the intervention to examine change in LA. The LAS was administered in Turkish, which matched participants’ first language and therefore required no translation. This helped reduce potential comprehension-related measurement error. The scale was used with permission. Qualitatively, participants in the experimental group produced weekly Padlet reflections and a final opinion paper, providing an emic account of how the SEL-aligned instruction shaped their learning experiences. The qualitative strand was embedded within the experimental arm to elaborate and help explain the quantitative patterns, and integration was undertaken at the interpretation stage.

Procedure

As outlined in Tables 1 and 2, the seven-week, SEL-enriched program integrated face-to-face sessions in the Independent Learning Center (ILC), a self-access learning facility providing computer-based materials, internet access, and print resources for independent and group study (Uzun, 2014), with structured out-of-class activities explicitly targeting self-awareness and social awareness. To illustrate how the program supported LA, we present two exemplar tasks from Week 4 (self-awareness) and Week 5 (social awareness). Each task followed a before, during, and after sequence: (a) a pre-session Padlet prompt serving as an advance organizer; (b) guided discussions in the ILC to scaffold communicative speaking and strategy use; and (c) a post-session Padlet reflection to consolidate learning and plan next steps. This recurring sequence reflects an adapted Gradual Release of Responsibility approach in which support is progressively faded from guided collaborative work toward independent reflection and planning (Fisher & Frey, 2008).

Table 1

SEL Intervention Overview (Self-Awareness)

Table 2

SEL Intervention Overview (Social awareness)

Data Collection Instruments

Data were collected using one quantitative measure and two qualitative sources (see Table 3). Using multiple sources enabled methodological triangulation and strengthened the credibility of the findings by allowing convergence across outcomes and participant accounts (Denzin, 2012). In addition, the qualitative sources provided explanatory insight into how the SEL-enriched instruction was experienced and how it may have supported LA.

Table 3

Data Collection Instruments

Data Analysis

Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS 28. LAS total scores were treated as approximately interval-level. Prior to inferential analyses, the data were screened for outliers and checked for assumptions relevant to t tests. All tests were two-tailed with alpha set at .05. Analyses proceeded as follows: (1) descriptive statistics were computed for each group at pre-test and post-test (Table 4); (2) an independent-samples t test on pre-test scores examined baseline equivalence (Table 5); (3) paired-samples t tests within each group assessed pre-to-post change (Table 6); and (4) an independent-samples t test compared gain scores (post–pre) between groups, with Cohen’s d reported as an effect size (Table 7).

Qualitative Analysis

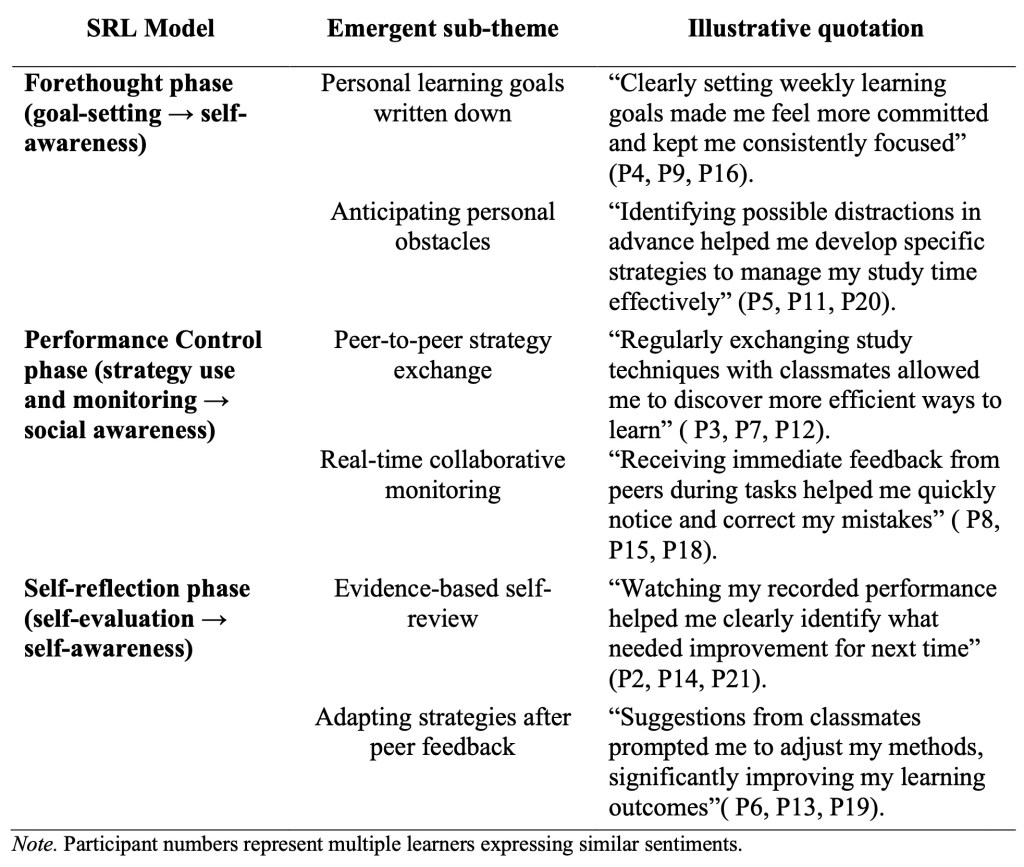

Qualitative data from Padlet reflections and final opinion papers (Table 8) were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2021) with a primarily theory-driven, deductive orientation informed by Zimmerman’s self-regulated learning (SRL) model (Zimmerman, 2000). The analysis involved repeated close readings for familiarisation, line-by-line initial coding, and the organization of codes into higher-order patterns mapped to the SRL phases: (1) forethought (goal setting), (2) performance control (strategy use and monitoring), and (3) self-reflection (self-evaluation). Throughout coding, the researcher attended specifically to how participants’ accounts indexed self-awareness and social awareness in relation to these self-regulatory processes. To enhance analytic credibility, an audit trail and analytic memos were maintained, and preliminary patterns were reviewed through participant feedback with six volunteers. In addition, a large-language model (ChatGPT) was used as an auxiliary analytic lens to surface alternative coding suggestions and potential blind spots; final coding decisions and theme development remained researcher-led.

Findings

The findings unfold in two aligned strands. Quantitative results first establish how LA scores shifted during the intervention, highlighting both within-group gains and between-group contrasts. The ensuing qualitative themes then contextualise these score changes, revealing how participants drew on CASEL’s self- and social awareness competencies across SRL phases. Together, the strands offer a coherent account of not only how much autonomy improved but also how learners enacted that improvement.

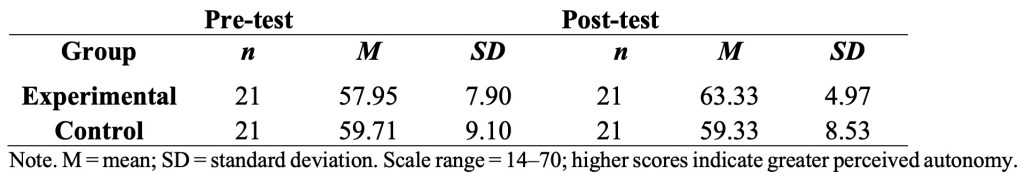

Table 4 shows that pre-test autonomy scores were comparable in the experimental group (M = 57.95, SD = 7.90) and the control group (M = 59.71, SD = 9.10), suggesting similar starting levels (see Table 5 for the baseline comparison). At post-test, the experimental group’s mean autonomy score increased (M = 63.33, SD = 4.97), whereas the control group’s mean remained largely stable (M = 59.33, SD = 8.53). The smaller post-test standard deviation in the experimental group suggests reduced variability in autonomy scores following the intervention.

Table 4

Descriptive Statistics for Autonomy Scale Scores

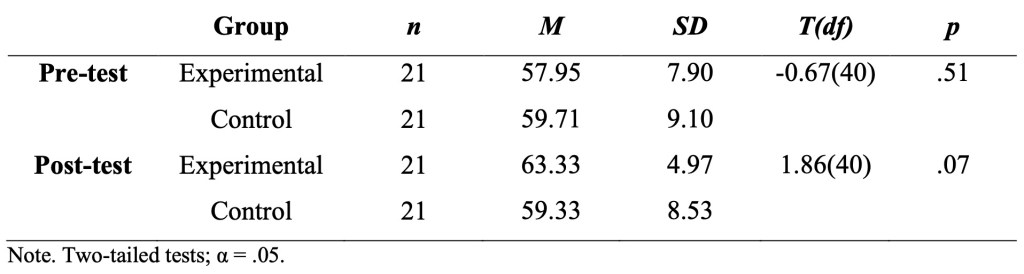

Table 5 reports independent-samples t tests comparing the experimental and control groups at pre-test and post-test. The pre-test comparison indicated no statistically significant group difference, t (40) = −0.67, p = .51, supporting baseline comparability. At post-test, the between-group difference was not statistically significant at α = .05, t (40) = 1.86, p = .07, although the mean difference was in the expected direction. The primary between-group test of intervention impact is therefore evaluated using gain scores (Table 7).

Table 5

Experimental and Control Groups’ Independent-Samples t Test Scores

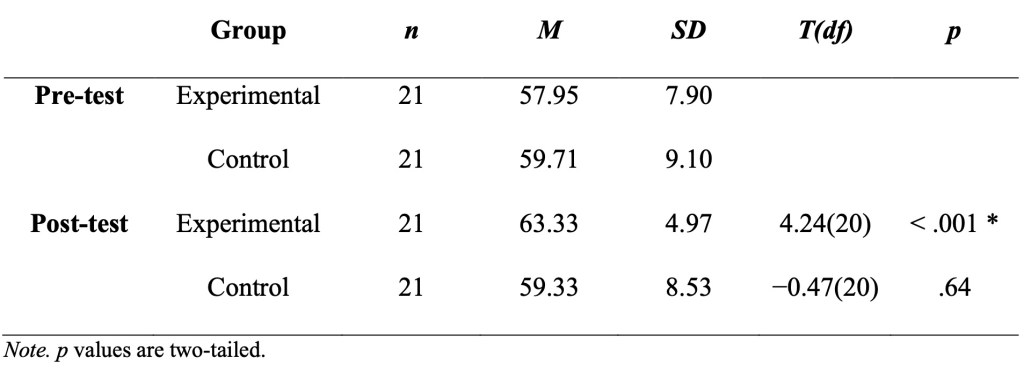

Table 6 illustrates within-group changes in LA from pre-test to post-test. The experimental group showed a statistically significant increase in LA scores from pre-test (M = 57.95, SD = 7.90) to post-test (M = 63.33, SD = 4.97), t (20) = 4.24, p < .001. In contrast, the control group did not show a statistically significant change (pre-test: M = 59.71, SD = 9.10; post-test: M = 59.33, SD = 8.53), t (20) = −0.47, p = .64. Taken together, these within-group results are consistent with an intervention-related improvement in autonomy in the experimental group.

Table 6

Experimental and control groups’ paired-samples t tests scores

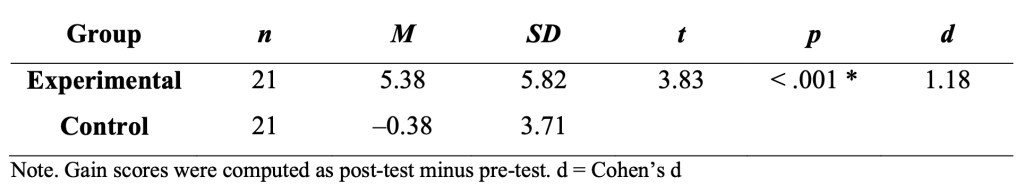

Table 7 reports an independent-samples t test comparing gain scores (post-test minus pre-test) between groups. The experimental group showed a substantial increase in learner autonomy (M = 5.38, SD = 5.82), whereas the control group showed little change on average (M = −0.38, SD = 3.71). The between-group difference in gain scores was statistically significant, t (40) = 3.83, p < .001, with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.18). These results provide strong quantitative evidence consistent with an intervention-related improvement in learner autonomy.

Table 7

Independent-Samples t Test Results for Change (Pre-Post) in LA

Table 8 summarises how participants’ reflections indexed autonomy-relevant processes across Zimmerman’s SRL phases, with patterns interpreted in relation to CASEL-aligned competencies of self-awareness and social awareness. In the forethought phase, learners described becoming more intentional about goal setting by writing down personal learning goals, which helped sustain commitment and focus (e.g., P4, P9, P16). They also reported anticipating likely obstacles and translating these into concrete plans for managing study time and attention (e.g., P5, P11, P20). In the performance control phase, participants’ accounts emphasised socially mediated regulation through peer interaction. Peer-to-peer strategy exchange was described as a resource for discovering more effective approaches to learning (e.g., P3, P7, P12), while real-time collaborative monitoring and feedback supported noticing and correcting errors during tasks (e.g., P8, P15, P18). In the self-reflection phase, learners reported engaging in evidence-based self-review (e.g., watching recorded performance) to identify areas for improvement (e.g., P2, P14, P21), and adapting subsequent strategies in response to peer feedback (e.g., P6, P13, P19). Overall, these themes help contextualise the quantitative gains by illustrating plausible mechanisms through which self- and social-awareness-oriented activities supported self-regulatory engagement and the enactment of LA.

Table 8

Qualitative Themes mapped onto Zimmerman’s SRL Phases and CASEL Competencies

Discussion

The results of this study provide converging quantitative and qualitative evidence that SEL competencies, self-awareness and social awareness, in a HE L2 course can foster LA. Quantitatively, the experimental group that underwent the 7-week SEL-infused curriculum showed higher gains on the LAS compared to the control group. Qualitatively, learners’ Padlet reflections and opinion papers illustrated how this growth in autonomy took shape. Learners in the SEL-integrated class reported heightened awareness of their own learning processes, more confidence in self-directed study, and greater willingness to collaborate with peers. These self-reported changes align with known benefits of SEL in L2 education, such as improved learner engagement, reduced anxiety, and enhanced interpersonal skills (Bai et al., 2024; Billy & Garriguez, 2021). Notably, the qualitative data help explain why the SEL-infused intervention succeeded in promoting LA. Learners mentioned that guided self-reflection (a key component of self-awareness) helped them identify their strengths, weaknesses, and needs in learning. This mirrors findings that self-awareness plays a critical role in improved learning, enabling learners to focus efficiently on what they need to learn (Yazigy, 2021). In this study, as learners became more aware of their emotions and habitual learning practices, they were better able to set personally meaningful goals and monitor their progress, aligning with Storey’s (2019) findings on the role of SEL-informed instruction in strengthening self-regulatory learning.

Furthermore, learners in the experimental group reported a stronger sense of community and improved skills in understanding others, evidence that the social awareness component of SEL was actively at work. They described activities like peer feedback, group problem-solving, and discussions of personal experiences, which cultivated empathy and active listening. These SEL skills created a more supportive, trusting learning environment, in which students felt safe to take risks and were more inclined to share ideas or ask questions. Such an environment can promote LA by providing teacher and peer-based social support that strengthens learners’ interaction engagement, thereby creating sustained opportunities to practice self-directed learning behaviours (Liu et al., 2023). In other words, LA in L2 learning does not develop in isolation; rather, it is nurtured in collaborative environments where learners feel emotionally secure and mutually supported (Little, 2015). The salience of this social dimension was evident in our participants’ accounts, which highlighted increased peer learning and empathy. This pattern aligns with prior work suggesting that SEL-informed classroom norms, such as cooperation and respectful communication, can strengthen peer collaboration and foster more authentic interaction in L2 settings (Melani et al., 2020). When SEL is integrated into learner-centred pedagogy, it may initiate a virtuous cycle in which learners become progressively more capable of directing their learning and approaching new challenges with greater confidence. Our SEL group appeared to exemplify this process. As learners became more self-aware and socially attuned, they reported greater willingness and capacity to initiate learning tasks, regulate their study habits, and extend their learning beyond the classroom.

It is also worth noting that our mixed-methods design revealed nuances that a single method might have overlooked. Quantitatively, the overall pattern indicated a positive shift in LA in the experimental group; however, this improvement was not uniform across all learners over the seven-week period. A small number of final opinion papers mention discomfort with the increased responsibility, despite voluntary participation, or challenges in balancing collaborative learning with personal self-management. These accounts help contextualise the quantitative gains by underscoring that autonomy is a complex, developmentally emergent capacity rather than an immediate outcome of short-term instructional change. Importantly, voluntary participation does not necessarily mean that a program will align equally well with every learner’s needs, readiness, or preferred learning orientations; heterogeneous responsiveness is therefore an expected feature of educational interventions rather than evidence that the program contradicts its pedagogical intent. This variability in responsiveness highlights the importance of teacher training that equips instructors to diagnose differing readiness for autonomy and to calibrate SEL-informed scaffolding (e.g., by sequencing responsibility, offering structured choice, and gradually releasing support to meet learners where they are).

Limitations

While these findings are encouraging, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the intervention was relatively brief (7 weeks); given that learner autonomy is likely to develop over longer trajectories, the present results primarily reflect short-term change. Second, because the reflections were produced in English as an L2, some intended nuance may not have been fully expressed. Finally, the single-site context and small sample size limit the transferability of the findings, as contextual factors such as proficiency level, institutional culture, and instructor expertise in SEL may shape the observed effects.

Recommendations for Teacher Training and Institutional Support

A practical route to sustaining LA is to foreground teacher autonomy in professional learning by giving L2 educators genuine voice and choice, protected time for reflection, and collegial support (Üstündağ-Algın & Karaaslan, 2023; Üstündağ-Algın et al., 2025). Teacher training can operationalise this through brief co-designed reflection prompts on emotions and values, lightweight peer-feedback routines, and mentoring or advising conversations that help educators make sense of their work and act with agency (Üstündağ-Algın, 2023; Üstündağ-Algın et al., 2025). Evidence from blended L2 learning further suggests that flexibility without sufficient guidance can increase the need for monitoring and structured support, particularly among lower-achieving learners, reinforcing the case for systematic autonomy-building training alongside instructional innovation (Karaaslan & Kılıç, 2019). Institutions can sustain this ecology by protecting time for recurring professional learning, aligning recognition systems with inquiry-oriented teaching, and modelling empathy-based leadership that normalises sharing and collaborative decision-making (Üstündağ-Algın et al., 2022).

Conclusion

By embedding self-awareness and social awareness activities into an L2 course, this study demonstrated measurable gains in LA, supported by learners’ own accounts of change. Situated within the broader literature, the findings suggest that SEL can provide a strong foundation for autonomy by addressing emotional and social dimensions of learning that are often underdeveloped in traditional instruction. Despite its contextual and methodological constraints, the study reinforces the view that effective L2 education extends beyond linguistic input and includes the development of self-directed, emotionally aware learners. For educators and program designers, the implication is that SEL-informed instruction can strengthen LA, particularly when accompanied by teacher training that equips instructors with the knowledge and tools to integrate SEL meaningfully into L2 learning. Ultimately, such integration may help foster learners who are proficient in English, resilient, reflective, and prepared to thrive beyond the classroom.

Notes on the Contributor

Pınar Üstündağ-Algın is a Ph.D. candidate in Applied Linguistics and an EFL/Turkish instructor at Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Türkiye. Her interests include workplace well-being, emotions, mentoring, SEL, method design, and ecological perspectives in L2 education. pinarustundag81@gmail.com

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to my wonderful students, who volunteered at every stage of this research with enthusiasm and generosity; their curiosity and commitment made the study possible. I also extend my heartfelt thanks to Dr. Hatice Karaaslan for her invaluable support throughout the implementation, including her active engagement with students during Padlet reflections and the Independent Learning Center (ILC) sessions. Finally, I express my sincere appreciation to the reviewers and editors for their time, expertise, and constructive feedback.

References

Andersson, S., & Nakahashi, M. (2023). The future role of online consultations within self-access learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.37237/140102

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Bai, B., Shen, B., & Wang, J. (2024). Impacts of social and emotional learning (SEL) on English learning achievements in Hong Kong secondary schools. Language Teaching Research, 28(3), 1176–1200. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211021736

Billy, R. J. F., & Medina Garríguez, C. (2021). Why not social and emotional learning? English Language Teaching, 14(4), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v14n4p9

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Chen, H., & Yu, Y. (2022). The impact of social‑emotional learning: A meta‑analysis in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1040522. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1040522

Chong, S. W., & Reinders, H. (2022). Autonomy of English language learners: A scoping review of research and practice. Language Teaching Research. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221075812

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2025). What is the CASEL Framework? https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/what-is-the-casel-framework/

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage

Denzin, N. K. (2012). Triangulation 2.0. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6(2), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689812437186

Durlak, C. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., & Taylor, R. D. (2011). Impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2008). Better learning through structured teaching: A framework for the gradual release of responsibility. ASCD.

Gardner, D., Lau, K., Tseng, M. L., Yu, L-T., & Yuan, Y-P. (2023). Language Learning beyond the classroom in an Asian context: Obstacles encountered. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(2), 106–135. https://doi.org/10.37237/140202

Güven-Yalcin, G. (2021). The learning advisory program club events and well-being: Regular clubbers’ reflections on their experiences. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 12(3), 212–230. https://doi.org/10.37237/120303

Herasymenko, L., & Muravska, S. (2024). Social-emotional learning in foreign language classes at higher education institutions: From theory to practice. ScienceRise: Pedagogical Education, 4(61), 20–25. https://doi.org/10.15587/2519-4984.2024.311511

Karaaslan, H., & Kılıç, N. (2019). Students’ attitudes towards blended language courses: A case study. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 15(1), 174–199. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/jlls/article/547699

Ko, M.-H., Jung, G., & Kim, J. E. (2024). Self-regulated learning and digital behavior in university students in an online L2 learning environment. English Teaching, 79(4), 143–163. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1459925.pdf

Little, D. (2007). Language learner autonomy: Some fundamental considerations revisited. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.2167/illt040.0

Little, D. (2015). University language centres, self-access learning and learner autonomy. Recherche et pratiques pédagogiques en langues, 34(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.4000/apliut.5008

Liu, X., Zhou, M., & Guo, J. (2023). Effects of EFL learners’ perceived social support on academic burnout: The mediating role of interaction engagement. SAGE Open, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231212725

Mahoney, J. L., Weissberg, R. P., Greenberg, M. T., Dusenbury, L., Jagers, R. J., Niemi, K., Schlinger, M., Schlund, J., Shriver, T. P., VanAusdal, K., & Yoder, N. (2021). Systemic social and emotional learning: Promoting educational success for all preschool to high school students. American Psychologist, 76(7), 1128–1142. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000701

Melani, B. Z., Roberts, S., & Taylor, J. (2020). Social emotional learning practices in learning English as a second language. Journal of English Learner Education, 10(1), Article 3. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/jele/vol10/iss1/3

Murray, G. (2014). The social dimensions of learner autonomy and self-regulated learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(4), 320–341. https://sisaljournal.org/archives/dec14/murray/

Murray, G. (2018). Self-access environments as self-enriching complex dynamic ecosocial systems. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 9(2), 102–115. https://doi.org/10.37237/090204

Mynard, J., & Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2022). Self-determination theory: A proposed framework for self-access language learning. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning, 4(1), e414522. https://doi.org/10.52598/jpll/4/1/5

Mynard, J., Kato, S., & Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2023). Learner and advisor perceptions of online advising during a pandemic. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(1), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.37237/140104

Mynard, J. (2024). Self-access language learning support in Europe: Observations and current practices. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 15(2), 258–279. https://doi.org/10.37237/150209

Nguyen, S. V., & Habók, A. (2021). Designing and validating the learner autonomy perception questionnaire. Heliyon, 7(4), e06831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06831

Orakcı, Ş., & Gelişli, Y. (2017). Learner Autonomy Scale: A scale development study. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 5(4), 25–35.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

Pentón Herrera, L. J. (2020). Social-emotional learning in TESOL: What, why, and how. Journal of English Learner Education, 10(1), Article 1. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/jele/vol10/iss1/1

Stringer, T. (2024). A conceptual framework for emergent language learner autonomy – a complexity perspective for action research. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2024.2371505

Storey, M. (2019). Engaging minds and hearts: Social and emotional learning in English Language Arts. Language and Literacy, 21(1), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.20360/langandlit29355

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Development, 88(4), 1156–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12864

Uzun, T. (2014). Learning styles of independent learning centre users. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(3), 246–264. https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep14/uzun/

Üstündağ-Algın, P. (2022). “If I don’t get lost, I will never find a new route”: Engaging with my mentee in my first mentoring session. Relay Journal, 5(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/050205

Üstündağ-Algın, P., & Karaaslan, H. (2023). Teacher autonomy webinar: Ebru Sınar-Okutucu & Metin Esen. IATEFL LASIG Newsletter (Issue 83), 28–32.

Üstündağ-Algın, P., Karaaslan, H., & Murphey, T. (2022). Leader-ship as an empathy-based sharing-caring-ship of partnered ethical-ecological teaching and mentor shipping. Relay Journal, 5(2), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/050203

Üstündağ-Algın, P., Karaaslan, H., & Kılıç, N. (2025). PRISM model for workplace well-being: Enhancing autonomy-supportive teaching. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(3), 566–590. https://doi.org/10.37237/160305

Weissberg, R. P. (2019). Promoting the social and emotional learning of millions of school children. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(1), 65–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618817756

Yazigy, R. (2021). Raising the EFL’s learner autonomy via self-awareness and language awareness techniques. Journal of Neurosurgery Imaging and Techniques, 6(2), 405–417. https://www.scitcentral.com/documents/6c19e509f3d7937967ea8cddf8dc3a34.pdf

Yu, B. (2023). Self-regulated learning: A key factor in the effectiveness of online learning for second language learners. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1051349. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1051349

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–39). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50031-7