Junko Carter-Yamashita, Seikei Institute for International Studies, Seikei University, Japan. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6805-3588

Carter-Yamashita, J. (2025). Autonomous learning support outside the classroom: Focusing on the planning and reflection phases of self-regulated learning Theory. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 16(4), 635–652. https://doi.org/10.37237/160403

Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine the effects of providing guidance and opportunities for learners to engage in autonomous learning outside the classroom, with a specific focus on the forethought and self-reflection phases of self-regulated learning theory. The seven-week learning support using a self-study log provided Japanese language learners with opportunities to visualize their out-of-class learning activities. As a result, even within a short period of time, learners acquired stronger self-reflection skills compared to the control group. This study demonstrates that support based on self-regulated learning theory can solidify and enhance Japanese language learners’ self-regulation skills during out-of-class learning, providing valuable insights for Japanese language instructors aiming to cultivate learner autonomy. Based on the findings, future recommendations include interventions that provide specific support for students who struggle with concrete planning and instruction in strategies for effective self-regulated learning. Additionally, fostering learners’ self-efficacy through scaffolding and acknowledging the role of teacher feedback may further contribute to their self-regulation.

Keywords: autonomous learning, self-regulated learning, goal setting, self-reflection, Japanese language education

One of the primary roles of Japanese language teachers is to support their students in learning Japanese. However, it becomes extremely difficult for teachers to monitor students’ progress after class is over and they have left the classroom. A few hours of classroom activities per week are insufficient; therefore, it is important for students to develop the ability to manage their own learning outside the classroom (Aoki & Nakata, 2011). Northwood and Thomson (2012) observed that students who continue taking Japanese language classes at foreign universities voluntarily engage with the language outside the classroom. How, then, can learners develop such habits? Is it possible for teachers to scaffold the acquisition of these skills?

These questions raise the issue of how such habits are cultivated and whether teachers can scaffold the development. In the field of Japanese language education, many researchers have focused on autonomous learning. Apduhan (2008) conducted an interview-based study on the autonomous learning practices of international undergraduate students after arriving in Japan. Other studies, such as Miyake and Fukushima (2005) and Suzuki et al. (2020), have investigated the role of teachers in supporting autonomous learning. The Japan Foundation Japanese-Language Institute, Kansai (2010) reported on a practical study that employed portfolios to foster autonomous learning.

While these studies have focused on guiding and supporting autonomous learning through classroom activities, there has not been sufficient attention given to how learners engage in autonomous learning outside the classroom and how such learning can be supported. To address this gap, the present study draws on the theory of self-regulated learning to conduct practical research and aims to contribute to a better understanding of how autonomous learning can be effectively supported in Japanese language education.

Literature Review

Self-Regulated Learning

Self-regulated learning refers to learning in which learners actively engage in systematic metacognition, motivation, and learning strategies to achieve their goals (Schunk & Zimmerman, 1998). In this theory, learners are assumed to take an active role in the learning process and effectively regulate and promote their progress. The cyclical model of self-regulated learning proposed by Zimmerman and Campillos (2003) divides the learning process into three distinct phases. In the forethought phase, important factors such as goal setting, strategy development, self-efficacy, expectations, interest in the task, and goal orientation are involved in task analysis. The performance phase involves self-observation and control through monitoring. The final self-reflection phase leads to evaluation, including causal attributions and emotional reactions. In other words, self-regulated learners set goals, develop plans to achieve those goals, employ strategies and monitoring to ensure the execution of those plans. Once goals are achieved, learners self-evaluate their learning, engage in introspection, and transition to the next cycle of goal setting. Through this cyclical and dynamic process, learners build their self-regulation skills and advance their learning autonomously (Zimmerman, 2008a).

The cyclical nature of self-regulated learning, with its focus on goal-setting, performance monitoring, and self-evaluation, has made it a valuable framework for designing educational interventions in second language acquisition (SLA). The following section discusses how self-regulated learning theory has been applied in previous research and how these insights inform the approach taken in the present study.

Educational Support Applying Self-Regulation Theory

Several studies in SLA have applied models of self-regulated learning, such as those by Nishida and Kuga (2018) and Ninomiya (2005), both conducted in Japan. However, most of these studies focus on classroom-based learning. Supporting learners outside the classroom presents distinct challenges, particularly in promoting and evaluating self-regulated learning during the performance phase. Reigeluth et al. (2016) argue that effective self-regulated learning support requires clearly defined learning goals and continuous self-assessment, which correspond to the forethought and self-reflection phases in Zimmerman’s cyclical model. Based on this framework, the present study focuses on goal setting and self-evaluation as core components of self-regulated learning support outside the classroom.

Sim (2007) conducted an intervention based on the self-regulated learning framework in a university preparation program for ESL learners. The treatment group engaged in weekly goal setting, reflection on English use outside the classroom, and strategy planning. While the study reported improvements in learners’ beliefs about autonomy and self-confidence, it primarily focused on affective outcomes and did not examine how learners’ actual use of self-regulated learning strategies changed as a result of the support.

Goda et al. (2014) investigated learners’ planning and reflection in relation to out-of-class study time and English proficiency. However, their analysis was based on the assumption that the amount of study time indicates the degree of learner autonomy. When time management is poor, even extended study hours may not lead to satisfactory results, and the development of self-efficacy can be hindered (Zimmerman et al., 1996). Therefore, in order to accurately assess whether learners are engaging in autonomous learning, it is necessary to use indicators that can evaluate their behavioral strategies.

These studies highlight the potential of support that involves goal setting and reflection based on self-regulated learning theory. However, previous studies have not clearly shown how such support affects learners’ actual strategic behavior in autonomous learning contexts. To address this issue, the present study offers structured support for out-of-class learning, focusing on planning and reflection within the framework of self-regulated learning. A self-study log was implemented as a practical tool to facilitate this process. To evaluate the effectiveness of the support, a questionnaire developed by Ishikawa and Kogo (2016) was used to assess learners’ self-regulated learning skills, specifically targeting the forethought and self-reflection phases of Zimmerman’s cyclical model. By comparing the results of a supported group and a control group, the study aims to explore how support grounded in self-regulated learning theory can influence learners’ autonomous learning behaviors in the context of Japanese language education.

Method

Participants

Twenty-eight international students (11 males; 17 females) participated in the study. The survey was conducted in Japanese language classes at a certain public university in Japan. The average age of the students was 23.72 years old, and they had studied Japanese language for an average of one year and five months.

Participants were divided into an experimental group (n = 15) and a control group (n = 13). Both groups were enrolled in late beginner- to early intermediate-level Japanese language classes. Two parallel Japanese classes at the same proficiency level were offered during the same term; therefore, one class was designated as the experimental group and the other as the control group. The students represented a diverse range of nationalities, classified as follows: 8 Chinese, 4 Indonesian, 3 French, 2 Thai, 2 Egyptian, 1 Taiwanese, 1 Brazilian, 1 Malaysian, 1 American, 1 Korean, 1 Vietnamese, 1 Swede, 1 German, and 1 Mexican.

Procedure

The survey was conducted in a Japanese language course targeting late beginner- to early intermediate-level learners. The course took place in the first quarter of 2018, spanning eight weeks with face-to-face classes. While no homework or assignments were given during the course, a written exam was administered on the final day of class.

The experimental group (n = 15) received treatment in the form of learning support outside the classroom. During the first class, students were given a self-study log and instructed on how to use it. They were asked to write their long-term and short-term goals and plan their learning activities for the following week. In the next class, they evaluated the extent to which they had achieved their previous week’s plan on a four-point scale, wrote a brief reflection of a few sentences, and were instructed to make a learning plan for the following week. This cycle was repeated for seven weeks. On the final day, they completed a questionnaire measuring self-regulated learning strategies and answered questions about their learning using the self-study log.

The control group (n = 13) received the same course content as the experimental group but without self-study learning support. On the last day of class, they also completed a questionnaire measuring self-regulated learning strategies.

Self-Study Log

The self-study log was used as a tool for learning support outside the classroom (Appendix A). It provided spaces for students to write (a) long-term goals envisioning their future several years ahead, (b) short-term goals as daily habits, and (c) records of their plans and reflections on out-of-class learning activities over seven weeks. Students were expected to complete the log during class and submit it to the teacher afterward. While a spare log sheet was provided for checking their records, many students were observed taking photos and saving them on their smartphones.

Self-Regulated Learning Skills Questionnaire

To measure the acquisition of self-regulated learning skills through the treatment, a questionnaire was prepared based on Ishikawa and Kogo (2016). The reason for using this scale was that it was developed based on Zimmerman’s learning cycle, which assumes goal setting and self-evaluation after learning and allows for the measurement of autonomous learning habits rather than memorization or exam-oriented cramming. From Ishikawa and Kogo’s (2016) study, which extracted five factors, four items1 were selected from each of the factors “developing learning plans” and “reflecting on learning methods,” as these are closely related to the planning and reflection within the model. All items were rated on a six-point scale (see Appendix B).

To qualitatively analyze the effects of the treatment, additional questions were included to examine the perceived effectiveness of using the self-study log. The question “Q1. How was self-study learning using the self-study log?” was answered on a four-point scale (“Not good at all,” “Not very good,” “Good,” “Very good”), along with a written explanation. Similarly, the question “Q2. Do you intend to set goals and engage in self-study learning in future studies?” was answered on a four-point scale (“Do not think so at all,” “Do not think so much,” “Think a little,” “Think a lot”), along with a written explanation. These questions were administered to students on the last day of class.

Data Analysis

The data obtained from the treatment in the experimental group are described. First, the long-term goals (a) and short-term goals (b) were categorized to understand the trends in the goals set by the participants. Regarding the descriptions of planning and reflection (c), categories were created based on Goda et al. (2014), and the frequency of each category was summarized. If there were multiple descriptions, the frequency values were added to the respective categories.

Finally, a comparison was made between the responses to the self-regulated learning skills questionnaire for the experimental group (N = 15) and the control group (N = 13). The average scores for each item were calculated, and the two groups were compared using an independent samples t test with a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Autonomous Learning Support Using the Self-Study Log

(a) Long-Term Goals and (b) Short-Term Goals

The long-term goals of the 15 students in the experimental group were “to be able to talk with Japanese people” (8 students), “to be able to live daily life in Japanese” (3 students), and “to improve my Japanese ability” (3 students). One participant set the goal of “getting a part-time job.”

The short-term goals for daily habits were classified into the following six categories. The most common was “study vocabulary and grammar” (7 students), followed by “practice conversation” (3 students), “review classwork” (2 students), “use expressions learned in class in daily life” (1 student), “watch anime” (1 student), and “watch movies in Japanese” (1 student). Although the students were not given any homework for the course, many of them planned to review vocabulary and grammar related to class content.

(c) Planning and Reflection Comments

Table 1 shows the frequency of the six planning categories and seven reflection categories derived from the students’ descriptions on the self-study log. In the planning category shown on the left side of the table, the largest number of comments fell under learning content (grammar, vocabulary, kanji), such as “I will learn the words of the lesson we learned today” or “I will study the passive form.” Most of the students wrote the contents of their short-term goals in the planning column and carried out their studies in a consistent manner. Other strategy-related categories also contained a substantial number of comments. There were 16 comments related to strategy use involving anime, manga, and movies (“I watch anime in Japanese”), 16 related to usage opportunities (“Speak with Japanese friends”), six related to date and time (“I study on weekends”), and five related to cognition (“Talk with people in Japanese using new vocabulary”).

The most common statements in the self-reflection category were positive self-reactions, with 30 positive comments indicating that study proceeded as planned, such as “The schedule was followed smoothly” and “Excellent! I reviewed all the words and grammar.” On the other hand, there were six comments related to negative self-reactions, such as “I didn’t study at all during the holiday.” In addition, statements falling into three causal attribution categories were found: 10 comments classified as external (“I’m very busy with my other classes”), eight as internal (emotional) (“It was fun. I already finished the show”), and seven as internal (strategic) (“I’m trying to remember the words I forgot by writing them down one more time”).

Moreover, there were four comments related to adaptation, in which learners reviewed their own plans, such as “I still need to study more because my vocabulary is very limited” and “I think I can learn more formal expressions from the news, so I will watch this.” Finally, there were 14 comments that simply described learning content (“I studied vocabulary today”).

Table 1

Frequency of Planning and Reflection by Category

(d) Feedback on the Autonomous Learning Support

In response to Q1 (“How was the autonomous learning using the self-study log?”), 11 out of 15 students answered “Very good.” The reasons included comments such as “I think it is good to check what I have done every week,” “I always tried to follow the plan made on this log,” “It is a good way to keep track,” “It is a good constraint for my study,” and “Having goals helps to find motivation.” There was also a comment such as “I wrote a lot of Japanese,” indicating that writing in Japanese in the self-study log itself had become an opportunity for language learning. On the other hand, four students answered “Not so good.” One student commented, “I was too busy to think much about this record.”

In response to Q2 (“Do you plan to set goals for your future studies?”), all students answered positively, with seven choosing “Very much” and eight choosing “A little.” The following comments were provided as reasons: “The self-study report also encourages me to study more outside the class! This record really helped me to check the studies of my Japanese skills,” “I study better with a goal in mind,” and “I learned that setting weekly goals is a good way to improve my Japanese skills.”

Self-Regulated Learning Skills Questionnaire

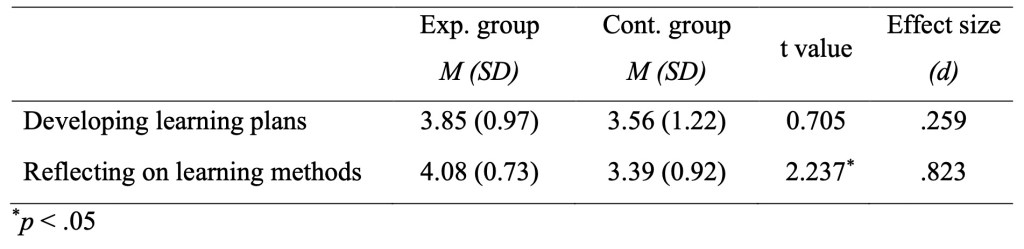

From the self-regulated learning skills questionnaire developed by Ishikawa and Kogo (2016), the factors “developing learning plans” and “reflecting on learning methods” were used. The average scores for the sub-items were calculated, and an independent-samples t test was conducted. The results showed no significant difference in developing learning plans ( t(26) = 0.705, p = .487, d = .259), but a significant difference was found in reflecting on learning methods ( t(26) = 2.237, p = .034, d = .823).

Table 2

Scores on the Self-Regulated Learning Skills Questionnaire by Factor

Discussion

Autonomous Learning Support Using Self-Study Log

In this study, self-study logs were used to support autonomous learning for 15 Japanese language learners. While the long-term goals were often vague, such as “becoming proficient in Japanese,” the short-term goals were more realistic and achievable because they involved specific plans. Schunk (2011) states that the three most important factors when setting goals are specificity, proximity, and difficulty. Having only long-term goals makes it difficult to determine what specific actions should be taken in daily learning. Therefore, setting more specific and achievable short-term goals in pursuit of long-term goals makes it easier to initiate learning. This explanation is also likely to apply when learners plan their out-of-class learning activities.

Regarding weekly study plans, the most common type of description was related to the content of what learners planned to study. Although writing style and content varied among students, many learners planned their out-of-class learning based on what they learned in class. Furthermore, several students included plans to watch anime, manga, or movies in Japanese. Similarly, there were 16 instances in which students mentioned their intention to advance their learning by speaking with friends or acquaintances in Japanese. Learning Japanese is not limited to classroom learning. Stepping out of the classroom, learners encounter opportunities to use Japanese in everyday life. Seeking such opportunities to input and use the target language is considered an important self-regulation strategy for L2 learners (Mezei, 2008). Consistent with Mezei (2008), learners’ comments in this study about integrating learning into daily life are likely to reflect effective language learning strategies.

Additionally, some students made plans to study at specific times or on specific days, such as “studying on weekends.” Time management is also related to metacognitive abilities involved in monitoring learning progress, and it is an important aspect of self-regulated learning (Wolters et al., 2017). When learners can metacognitively observe and adjust their learning processes to achieve their goals, the learning cycle continues, leading to the development of self-regulated learners. However, in this study, there were only five to six comments related to time management and cognition. These findings suggest that unless the self-study log is used effectively, it may not be sufficient to foster these abilities.

With respect to the category of reflection, self-reaction comments were the most frequent. Moreover, there were many comments related to causal attributions when learners reflected on the outcomes of their learning. These comments can be further categorized as positive vs. negative reactions and internal vs. external attributions. However, all of these descriptions correspond to strategies included in Zimmerman and Campillo’s (2003) cyclical model. Therefore, it can be suggested that the learners in this study were able to engage in reflection on their learning behaviors. Unlike the planning category, descriptions of learning content were relatively limited, with only 14 instances.

Acquisition of Self-Regulation Learning Skills

The results of the t test showed a significant difference between the groups in reflecting on learning methods, but no significant difference in developing learning plans. A possible explanation for this can be inferred from the descriptions in the self-study log presented in the previous section. Learners’ comments regarding their learning plans mainly focused on what to study rather than how to study. In other words, although learners were engaged in goal setting, their goals lacked the concrete strategies for achieving them – an essential element of strategic planning. This lack of specificity and depth likely prevented the activation of the cyclical process central to self-regulated learning. According to Zimmerman (2008b), proactive learners set goals that are specific, proximal, and challenging, whereas reactive learners tend to rely on vague and unstructured goals. From this perspective, it can be hypothesized that the underdeveloped ability to set sufficiently concrete goals contributed to the lack of significant improvement in developing learning plans, as measured by Ishikawa and Kogo’s (2016) framework.

In addition, the type of goal orientation may also have played a role. Previous studies have shown that goal setting based on different goal orientations – such as mastery-approach versus avoidance goals or performance-approach vs. avoidance goals (Elliot & McGregor, 2001), as well as intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation (Vansteenkiste et al., 2004) – can influence learning outcomes. In this study, no analysis was conducted based on goal orientation, nor was specific instruction provided to learners on how to write their learning plans. Future research could include instructional interventions that guide learners in concrete goal setting and strategic planning, and examine the effectiveness of such support using self-study logs.

On the other hand, learners’ reflections frequently included deep-level processing, such as self-reactions, causal attributions, and adaptations. Some learners noted that the self-study log helped them stay on track and follow through with their learning plans; for example, “I always tried to follow the plan made on this log” and “It is a good way to keep track.” These findings suggest that reflective activities promoted metacognitive monitoring and contributed to the development of self-regulated learning skills, which may help explain the significant improvement observed in reflecting on learning methods compared to the control group.

Reflective activity has been defined as “the process of thinking deeply about one’s language learning in order to take informed and self-regulated action towards language outcomes” (Mynard et al., 2023). Asking learners to write reflections using tools such as learning journals or diaries can help them develop metacognitive skills and strengthen their ability to regulate their own learning (Mynard, 2023). In this study, regularly writing reflections likely helped learners become more aware of their learning strategies and progress, leading to measurable gains in their ability to reflect on learning methods. These findings reinforce the potential of reflection-based activities to promote autonomous learning outside the classroom.

Interestingly, many learners also recorded positive self-reactions in their logs. By evaluating their learning positively, learners’ self-efficacy appeared to increase, which may have contributed to sustained engagement in the learning cycle. Self-efficacy, a key component of self-regulated learning theory (Bandura, 1986), is known to promote continued effort and persistence. If learners receive positive evaluations through their own learning experiences, they are likely to continue learning autonomously outside the classroom. Although this study did not directly measure changes in self-efficacy, these results suggest its potential influence. Future research could benefit from including emotional factors, such as self-efficacy, as additional variables when evaluating self-regulated learning outcomes, possibly drawing on Sim’s (2007) framework.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to provide support for autonomous learning based on Zimmerman’s model, to analyze the content of students’ out-of-class learning activities, and assess their self-regulated learning skills in order to explore the effectiveness of the support. The result indicated that certain self-regulation skills were acquired despite the relatively short duration of seven weeks, as evidenced by comparison with the control group.

Zimmerman’s cyclical model emphasizes the interconnection between forethought, performance, and self-reflection. The use of self-study logs in this study provided learners with structured opportunities for planning and reflection, thereby making their out-of-class learning activities more visible. Through repeated cycles of goal setting, evaluation, and reflection, learners appeared to develop greater awareness of their learning processes, which may have contributed to improvements in specific aspects of self-regulated learning.

Based on the finding that the ability to develop learning plans did not show significant improvement, future research should consider providing more explicit, intervention-based support for learners who struggle to create concrete plans. Guiding learners from vague goals toward specific and achievable ones may help foster strategic planning skills (Schunk, 2011). In addition, because self-regulated learning skills are teachable (Boekaerts, 1997), instructional approaches such as strategy modeling or peer feedback may further support learners’ development. It would also be valuable to examine emotional and motivational factors, particularly self-efficacy, which is a key component of Zimmerman’s model but was not directly measured in this study.

Overall, the findings suggest that learning support grounded in self-regulated learning theory can help structure learners’ out-of-class study and foster the development of certain self-regulation skills. This study offers pedagogical insights for Japanese language teachers seeking to promote learners’ autonomous learning beyond the classroom through structured reflection and planning support.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, although the two factors were theoretically selected from the questionnaire developed by Ishikawa and Kogo (2016), several items were omitted in the present study. In addition, due to the small sample size, reliability coefficients such as Cronbach’s alpha were not calculated. As a result, the measurement quality of the modified subscales cannot be fully evaluated, and the findings related to self-regulated learning skills should be interpreted as exploratory.

Second, this study did not employ a pre-test design. Without baseline measurements of self-regulated learning skills, it is not possible to rule out pre-existing differences between the experimental and control groups or to directly examine changes over time attributable to the intervention.

Finally, although the participants represented a diverse range of national backgrounds, the sample size was relatively small and drawn from a single Japanese university. This limits the generalizability of the findings to other learner populations or educational contexts. Future research should employ larger samples, pre–post designs, and validated measurement procedures to further investigate the effects of autonomous learning support on the development of self-regulated learning skills.

Despite these, this study demonstrated that support based on self-regulated learning theory can help structure learners’ out-of-class study and enhance certain self-regulation skills. The findings may serve as a useful reference for Japanese language teachers who aim to foster learners’ autonomous learning abilities.

Notes

1. The factor “reflecting on learning methods,” extracted in Ishikawa and Kogo’s (2016) study, consists of seven items. However, two items that did not apply to the autonomous learning support in this study were excluded: “I reflect on reasons for being unable to ask the teacher questions” and “I create a to-do list to prioritize learning tasks.” Additionally, the item “I reflect on reasons for performing poorly on tests or assignments” was also excluded because the survey was conducted before the exams.

Notes on the Contributor

Junko Carter-Yamashita is a lecturer at Seikei University, Japan. Her research interests include Japanese language education and second language acquisition, with a focus on motivation, self-regulated learning, task-based language teaching, and learner engagement.

References

Apduhan, K. (2008). Gakubu de manabu ryūgakusei no nihongo jiritsu gakusyū katei ni tsuite: Jūdan teki kikitori chōsa no bunseki [Autonomous Japanese language learning process for undergraduate foreign students: Insight from interviews]. Journal of Technical Japanese Education, 10, 41–46.

Aoki, N., & Nakata, Y. (2011). Gakushūsya autonomy: Nihongo kyōiku to gaikokugo kyōiku no tameni [Mapping the terrain of learner autonomy: Learning environments, learning communities and identities]. Hituzi Syobō Publishing.

Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359

Boekaerts, M. (1997). Self-regulated learning: A new concept embraced by researchers, policy makers, educators, teachers, and students. Learning and Instruction, 7(2), 161–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(96)00015-1

Elliot, A. J., & McGregor, H. A. (2001). A 2 × 2 achievement goal framework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(3), 501–519. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.3.501

Goda, Y., Yamada, M., Matsuda, T., Kato, H., Saito, Y., & Miyakawa, H. (2014). Jiko chōsei gakushū cycle ni okeru keikaku to reflection: Jugyō gai gakushū jikan to eigoryoku to no kankei kara [Plan and reflection of self-regulated learning: Perspectives of outside classroom learning hours and English proficiency]. Japan Journal of Educational Technology, 38(3), 269–286. https://doi.org/10.15077/jjet.KJ00009649929

Ishikawa, N., & Kogo, C. (2016). Daigaku tsūshin kyōiku katei no shakaijin gakusei ni okeru jiko chōsei gakushū hōryaku kan no eikyō kankei no bunseki [Causal analysis of self-regulated learning strategies used by adult students in university online courses]. Japan Journal of Educational Technology, 40(4), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.15077/jjet.40087

The Japan Foundation Japanese-Language Institute, Kansai (2010) Portfolio de jiritsu gakushū o unagasu: Kaigai de nihongo o manabu daigakusei no jiritsu gakushū shien [Scaffolding autonomy with portfolio: Autonomous learning support to university students learning Japanese overseas]. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://www.jfstandard.jpf.go.jp/pdf/jirei_04_full.pdf

Mezei, G. (2008). Motivation and self-regulated learning: A case study of a pre-intermediate and an upper-intermediate adult student. Working Papers in Language Pedagogy, 2, 79–104. https://doi.org/10.61425/wplp.2008.02.79.104

Miyake, W., & Fukushima, T. (2005). Jiritsu gakushū o kiban to shita kobetu taiōgata nihongo jugyō ni kansuru ichi kōsatsu: kyōshi no yakuwari o tegakari ni [Focusing on teachers’ role in Japanese classes: Based on the idea of autonomous learning]. Nihongo Kyōiku Ronshū [Journal of Japanese Language Education], 21, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.15084/00001881

Mynard, J. (2023). Promoting reflection on language learning: A brief summary of the literature. In N. Curry, P. Lyon, & J. Mynard (Eds.), Promoting reflection on language learning: Lessons from a university setting (pp. 23–37). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781800415591-005

Mynard, J., Curry, N., & Lyon, P. (2023). Promoting reflection on language learning: Introduction. In N. Curry, P. Lyon, & J. Mynard (Eds.), Promoting reflection on language learning: Lessons from a university setting (pp. 1–12). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781800415591-003

Ninomiya, R. (2015). Fukusū kōtō happyō to jiko naisei katudō no kōka: Jiko chōsei gakushū riron karano bunseki [Effects of making a presentation twice followed by reflection: An analysis based on self-regulated learning theory]. Journal of Global Education and Exchange, 6, 31–44. https://doi.org/10.15057/27451

Nishida, H., & Kuga, N. (2018). Jiko chōsei gakushū no riron ni motozuita “seito no jiritsuteki na manabi” o umidasu eigoka gakushū sidō program no kaihatsu to sono kōka [Development and effects of English teaching guidance program that creates “students’ autonomous learning” based on the theory of self-regulated learning]. Japan Journal of Educational Technology, 42(2), 167–182. https://doi.org/10.15077/jjet.42050

Northwood, B., & Thomson, C. (2012). What keeps them going? Investigating ongoing learners of Japanese in Australian universities. Japanese Studies, 32(3), 335–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371397.2012.735988

Reigeluth, C. M., Beatty, B. J., & Myers, R. D. (Eds.). (2016). Instructional-design theories and models, volume IV: The learner-centered paradigm of education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315795478

Schunk, D. H. (2011). Learning theories, an educational perspective: International edition. (6th ed.). Pearson Education.

Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (Eds.). (1998). Self-regulated learning: From teaching to self-reflective practice. Guilford Press.

Sim, M. S. (2007). Beliefs and autonomy: Encouraging more responsible learning. Novitas-ROYAL: Research on Youth and Language, 1(2), 112–136.

Suzuki, S., Hakuto, H., & Sugihara, Y. (2020). Jiritsu o unagasu jugyō ni okeru nihongo kyōshi no kizuki to sono keiki: Jiritsu gata class o hajimete tanto shita kyōshi A no jirei kara [How a Japanese language teacher fostering learner autonomy develops awareness in class: The case of a teacher managing a course fostering learner autonomy for the first time]. Japan Bulletin of Educators for Human Development, 23(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.20590/jaehd.23.1_11

Vansteenkiste, M., Simons, J., Lens, W., Sheldon, K. M., & Deci, E. L. (2004). Motivating learning, performance, and persistence: The synergistic effects of intrinsic goal contents and autonomy-supportive contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 246–260. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.246

Wolters, C. A., Won, S., & Hussain, M. (2017). Examining the relations of time management and procrastination within a model of self-regulated learning. Metacognition and Learning, 12, 381–399. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/s11409-017-9174-1

Zimmerman, B. J. (2008a). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 166–183. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.3102/0002831207312909

Zimmerman, B. J. (2008b). Goal setting: A key proactive source of academic self-regulation. In D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Motivation and self-regulated learning: Theory, research and applications (pp. 267–296). Taylor & Francis Group.

Zimmerman, B. J., Bonner, S., & Kovach, R. (1996). Developing self-regulated learners: Beyond achievement to self-efficacy. American Psychological Association. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/10213-000

Zimmerman, B. J., & Campillo, M. (2003). Motivating self-regulated problem solvers. In J. Davidson, & R. Sternberg (Eds.), The psychology of problem solving (pp. 233–262). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511615771.009

Appendix A

Self-Study Log Sheet

Appendix B

Self-Regulated Learning Skills Questionnaire

(based on Ishikawa & Kogo, 2016; originally developed in Japanese)

Please indicate the extent to which each statement applies to your thoughts or behaviors by selecting one option from the six-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = partially disagree, 4 = partially agree, 5 = agree, 6 = strongly agree).

1. Developing Learning Plans

- I make a detailed plan before I begin studying.

- I decide how much I will study today based on assignment deadlines or exam dates.

- I plan my study schedule by working backward from assignment deadlines or exam dates

- When I study, I decide what to complete and by what time.

- I set specific times of day for studying.

2. Reflecting on Learning Methods

- When I miss a deadline, I reflect on the reason.

- I evaluate whether my learning methods were effective.

- I reflect on whether I was able to follow my study plan.

- I create to-do lists to prioritize my learning tasks.

- I think about how I could study more efficiently.