Toshinori Yasuda, Tokyo University of Science, Japan. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1941-0299

Yasuda, T. (2023). Simple and effective advising practice: A semi-structured advising program for Japanese EFL learners. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(3), 306–336. https://doi.org/10.37237/140305

Abstract

Although advising in language learning (ALL) in the Japanese setting for English as a foreign language (EFL) is indispensable, its domestic dissemination remains in an embryonic stage. As a suggested solution, a semi-structured ALL program was developed in a recent study, whose effects are investigated in the present study. The newly developed program is tailored to lead learners toward subjective well-being with active engagement in language learning. Furthermore, it includes several novel and unique features such as specific tasks allocated to particular sessions. Therefore, the research questions regarding its effects are as follows: (1) To what extent do Japanese EFL learners achieve their active engagement and (2) subjective well-being through the semi-structured ALL program? (3) How do they evaluate the usefulness of the program? Quantitative data from 15 Japanese EFL advisees who underwent the semi-structured program were statistically analyzed, and the results were supported by qualitative data. Overall, the program contributed to Japanese EFL learners’ active engagement and subjective well-being. Moreover, participants recognized most of the program’s features as useful. However, some parts remain to be improved. The discussion section argues both aspects in as much detail as possible.

Keywords: advising in language learning, semi-structured program, subjective well-being with active engagement

Advising in language learning (ALL) is a relatively new educational practice. In addition to target language acquisition, at which traditional language teaching mainly aims, ALL focuses on fostering autonomous learners (Carson & Mynard, 2012). Through ALL services, language learners can identify their learning goals, choose and use effective learning strategies, motivate themselves, and evaluate their learning processes.

ALL is indispensable in a setting for English as a foreign language (EFL), such as in Japan, where learner autonomy is required for more active English learning because learners have insufficient opportunities for English input and output. Although ALL has received more attention in Japan than ever before, its dissemination remains in an embryonic stage. The registry provided by the Japan Association for Self-Access Learning (Japan Association for Self-Access Learning, 2022) includes 57 educational institutions that provide self-access learning services that may include ALL. There are three possible reasons for this.

First, ALL is sometimes time-consuming (Reinders, 2008). Depending on the type of ALL, some learners take a number of sessions for as many as several years. This style of ALL should be fully respected, as it provides generous support for learners. Meanwhile, an advisor must spend a considerable amount of time with specific learners only. Thus, many other learners may miss the benefits of ALL services. This may ultimately hinder the spread of ALL. One solution is to develop a shorter-period ALL program with a limited number of sessions that nonetheless works effectively.

Second, the advisors are sometimes confused about what they should do during each session. Unlike standard language teaching with predetermined curricula or syllabi, ALL typically follows flexible pathways (Gardner & Miller, 1999). Thus, it is natural for some, especially novice advisors, to be uncertain. This possible stagnation in the early stages of a career may prevent novices from smoothly becoming skillful advisors. Consequently, ALL would not be fully disseminated, owing to the limited number of experienced advisors. One possible solution is to develop an advising program with a clear structure that guides advisors on what they should do.

Third, an ALL service should ideally be provided with the approval of the institution to which the advisor belongs, as the service would be effective if flexibly coordinated with the institution’s language classes and credit system. This would result in a smoother dissemination of ALL. However, it is sometimes difficult to persuade organizations to open official ALL services. Possible reasons are as follows: First, as a dialogue-based ALL service is different from language teaching with a clear curriculum, some stakeholders (e.g., language instructors, program managers, or deans) may misunderstand it is a “mere chat” with a student. Second, because an ALL session sometimes involves language learners’ personal problems, the advisor must follow a strict privacy policy, which makes it difficult for the advisor to be more specific in explaining the ALL service to outsiders. Nevertheless, personnel involved in ALL should still fulfill their responsibilities if they want their institutions to officially adopt their services. As a solution, the contents of each ALL session should be schematically organized and visually shown so that they can be more easily understood.

Researchers in the field need to develop a specific ALL program that can address these issues and demonstrate its impact. This would allow for the smooth dissemination of ALL.

A Semi-Structured ALL Program

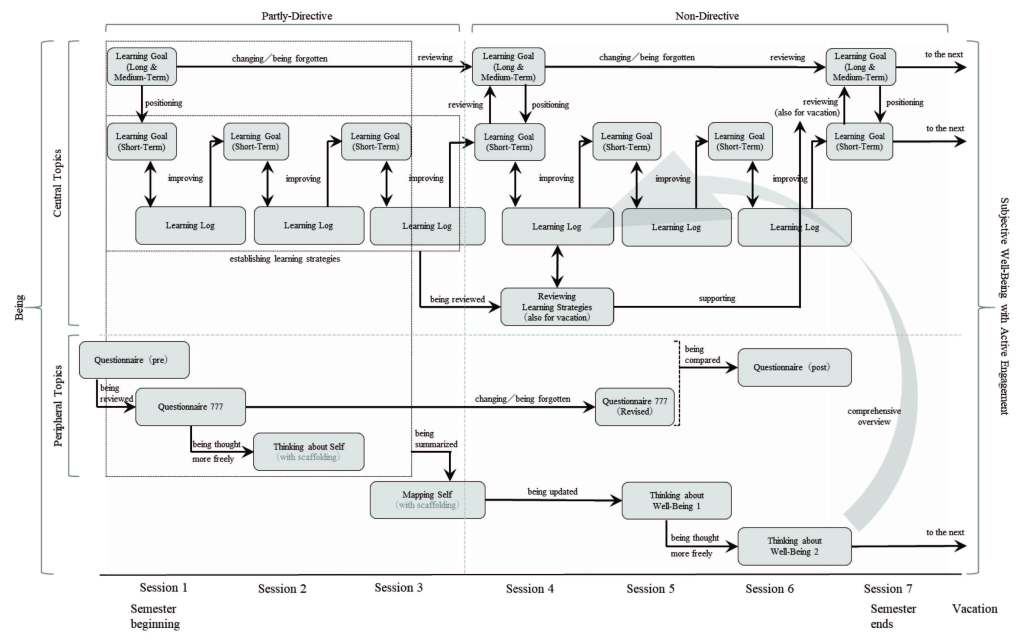

A semi-structured ALL program characterized by a limited number of sessions, assigned tasks that guide advisors on what they should do, and a visually schematized framework is a possible solution to these problems. Yasuda (2020) created a blueprint of a program based on various academic findings (e.g., Dörnyei, 2009, 2010; Ehrman & Leaver, 2002; Namikawa et al., 2012; Oxford, 1990; Sannomiya, 2008; Weaver, 2010). The program was then implemented with six Japanese EFL learners. Quantitative and qualitative data analyses were conducted to design the final version of the program, which is shown in Figure 1 (Yasuda, 2020).1 This section introduces both the outline and detailed structure of this ALL program based on Figure 1.

“Subjective Well-Being with Active Engagement” as a Goal of the ALL Program

The semi-structured program was devised to lead learners from their current level of being to an ideal future goal represented by the concept of subjective well-being with active engagement (see both the left and right ends of Figure 1). This was conceptualized by Yasuda (2020), who considered important psychological and philosophical findings.

Whereas subjective well-being typically includes a global assessment of all aspects of a person’s life, domain-specific satisfaction has also been investigated (Diener, 1984; Diener et al., 1999). Therefore, based on Diener (2012), subjective well-being in language learning was defined as “learners’ cognitive evaluations of satisfaction with their language learning” (Yasuda, 2020, p. 37). Furthermore, research has shown that some components, such as positive emotion, engagement, and meaning, are related to subjective well-being (e.g., Seligman, 2011). While the above definition basically refers to a language learner’s overall evaluation of satisfaction with a learning process, for a better understanding of the concept, it can fall into several subcategories, including a sense of fulfillment, self-acceptance, and self-actualization (Yasuda, 2020).

However, one serious issue is that subjective well-being could be an “anything-goes” concept if it included all the situations that led to learner satisfaction. For example, if learners immediately gave up their English learning without being seriously engaged in it, it would be doubtful whether they could achieve their true well-being (Yasuda, 2020). This implies that each “learner’s sincere effort towards his or her language learning” process is required to achieve true subjective well-being, which is defined as active engagement (Yasuda, 2020, p. 93). Building on Carson and Mynard (2012), active engagement should be attained by each learner’s daily efforts in selecting appropriate learning strategies and materials, planning, monitoring, and evaluating ongoing language learning, with adequate learning time. Subjective well-being cannot be easily obtained without such actual practice.2

Figure 1

Semi-Structured ALL Program

A Total of Seven Sessions

Assuming that the ALL program consists of one-on-one sessions between a learner and an advisor, it comprises seven 60–90-minute sessions, each of which takes place once every two weeks. Thus, its entire service is within one semester, which is a relatively short period (see the bottom of Figure 1).

After completing the service, learners usually have a long vacation, during which they must continue learning English without advising sessions. Therefore, the ALL program includes appropriate support to maintain learners’ success during the vacation period. For example, in the middle of the program, learners are given the task of thinking about what they want to learn during vacation. In the last session, they are also required to consider their long- and medium-term learning goals for the vacation based on their previous task results.

Partly-Directive vs. Non-Directive Phases

The semi-structured ALL program divides the seven sessions into partly-directive and non-directive phases (see the top of Figure 1). An advisor’s attitude should preferably be less directive in ALL (Carson & Mynard, 2012). Meanwhile, the significance of a directive attitude is emphasized as follows: “Through a combination of non-directive and appropriately introduced directive interventions, a learner can be supported in their autonomous learning endeavours” (Carson & Mynard, 2012, p. 9).

More specifically, for this semi-structured ALL program, advisors are allowed to make suggestions and offer opinions more directly in the former phase and are required to reduce the degree of directiveness in the latter. Among the most important points in the partly-directive phase is that the advisor should retain the role of a reflective listener and collaborator, rather than an instructor and leader (Gardner & Miller, 1999). For example, when suggesting language learning strategies, advisors should not directly provide knowledge about specific strategies as a one-way message. Instead, advisors should present multiple options and adopt a collaborative attitude that allows learners to choose better options.

Central vs. Peripheral Topics and Comprehensive Overview

As a language learning process can be affected by various factors, the semi-structured ALL program covers multiple topics using several tasks (see the rounded gray rectangles in Figure 1). The program divides them into central and peripheral topics (see the immediate inside of the very left of Figure 1). The former refers to more direct topics in a language learning process such as learning goals and strategies. The latter indicates various indirect impacts on language learning, including motivational factors, personality, and the influence of people (e.g., family members, friends, and teachers). A comprehensive overview process is not included in either the central or peripheral topics. This process combines and summarizes multiple aspects of both topics from a more objective perspective (see the bottom right of Figure 1; Mapping Self, Thinking about Well-Being 1 and 2).3

Specific Tasks and Flexible Dialogues

The semi-structured ALL program allocates each specific task, shown as a rounded gray rectangle in Figure 1, to each session. Meanwhile, flexible dialogues in line with each participant’s needs still play a central role. For example, although learners are usually required to share the results of the personality questionnaire in Session 1 (specific task), the dialogues can still be sufficiently flexible to extend through and beyond the topics of the questionnaire (flexible dialogue). Furthermore, each session is designed to afford sufficient time for free dialogue unrelated to any task (flexible dialogue).

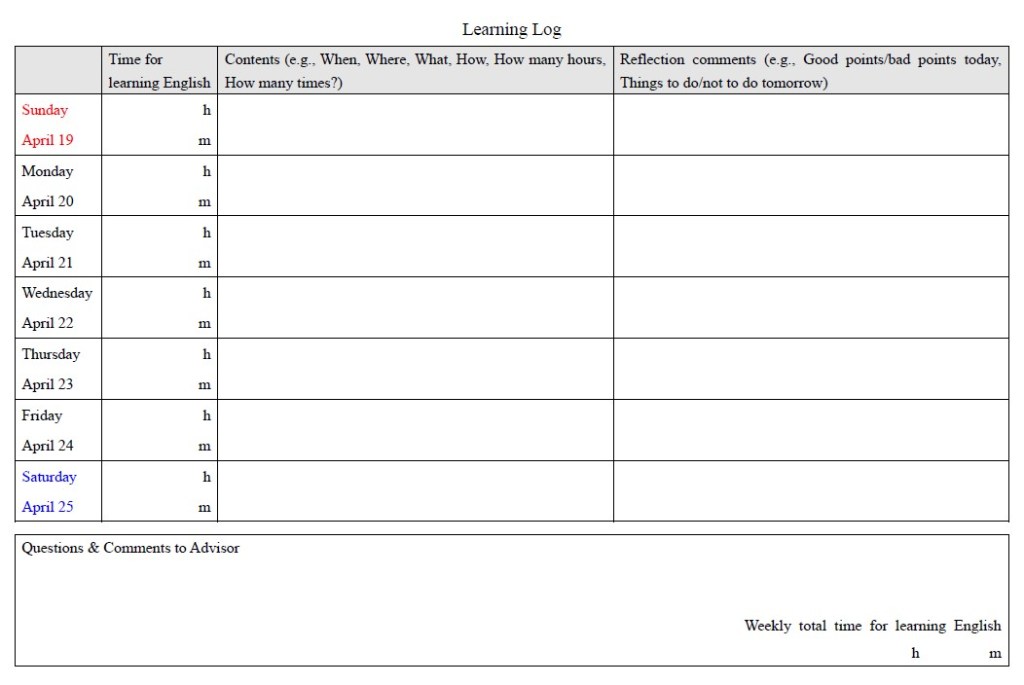

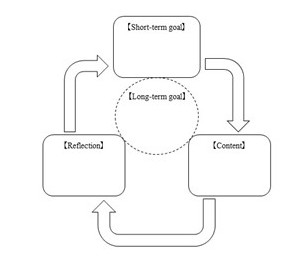

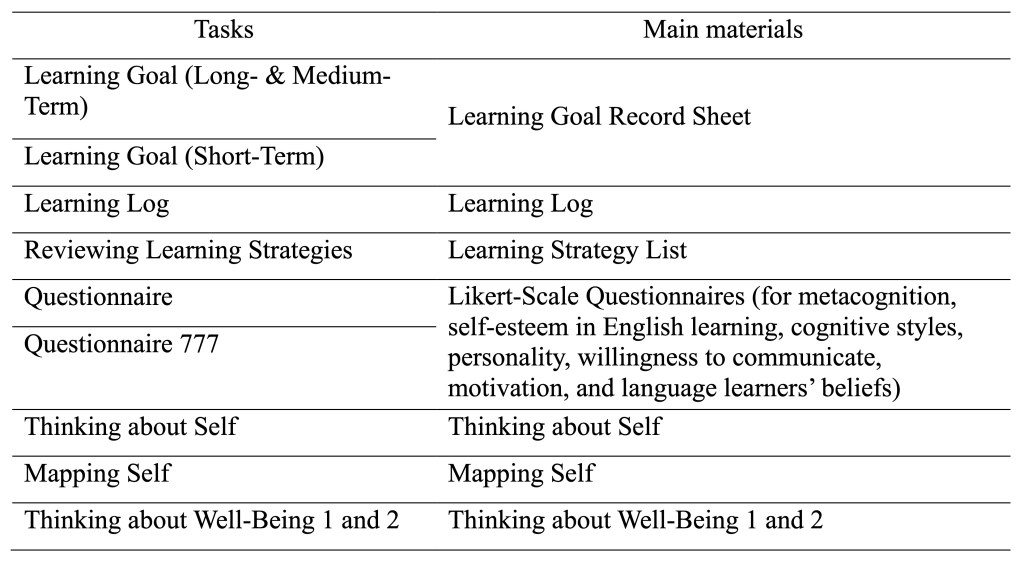

Each specific task is typically introduced using one or more dedicated materials. For example, learners keep a Learning Log that has a ready-made format, as shown in Figure 2. Additionally, in Mapping Self, they freely draw various influential factors in their language learning on a specific task sheet that has a pre-printed section in its center (Figure 3). Learners are expected to engage in these tasks conducted not only within each session, but also as take-home work. Table 1 lists the materials used for each task.

Figure 2

Learning Log

Note. This figure shows an English translation of the Learning Log. The semi-structured ALL program provided learners with an original Japanese version.

Figure 3

Mapping Self

Note. The figure on the top shows an English translation of Mapping Self. The semi-structured ALL program used the original Japanese version shown on the bottom, which also provides a sample result drawn by a learner (blurred for privacy).

Table 1

Main Materials Used in Each Task

Meaningful Relationships Among Tasks

The semi-structured program is also characterized by meaningful relationships among tasks (see the black arrows in Figure 1), which indicate why each task is allocated in a specific session. For example, in Session 1, learners are asked to complete Learning Goals and Questionnaires, which provide them with a trigger for identifying the direct or indirect factors impacting their language learning. In Session 2, they think more deeply about the effects of the indirect factors through a task called Thinking about Self. In Session 3, their ideas about direct and indirect factors are summarized into a meta-view in a task named Mapping Self. Meanwhile, the advisor can flexibly arrange each task based on the relationship diagram. For example, an advisor can wait for Mapping Self until the direct and indirect factors have been sufficiently discussed in previous sessions. In this case, Mapping Self may be conducted in Session 4 or 5. Moreover, by understanding these relationships among tasks, an advisor may be able to replace an allocated task with a new one.4

Research Questions

As stated above, while some critical issues have prevented the dissemination of ALL, such as time-consuming processes, advisors’ confusion over what they should do, and stakeholders’ misunderstanding of ALL practices, the semi-structured ALL program has significant advantages, including solutions to these problems. However, one serious issue is that the effects of this program on real language learners remain unclear. In other words, its impacts, such as how much learners achieve active engagement and subjective well-being, must still be investigated. Therefore, this study, which provided Japanese EFL learners with this ALL service, was guided by the following research questions:5

- To what extent do Japanese EFL learners achieve their active engagement through the semi-structured ALL program?

- To what extent do Japanese EFL learners achieve their subjective well-being through the semi-structured ALL program?

- How do Japanese EFL learners evaluate the usefulness of the semi-structured ALL program?

Method

Context

The semi-structured ALL program was conducted at a university in Japan offering four-year degree programs. The university does not have official self-access learning centers that are open to all students; however, some of the faculties have started their own ALL services. The ALL program in this study was developed by the author in a faculty that did not offer any ALL services. The author was an advisor who visited English classes, explained the ALL program, and recruited the participants. He clearly mentioned that although the ALL program would be offered as part of a research project, it was designed to maximize the benefits to each language learner. He also explained that while the target language was English, the ALL program would be offered in Japanese. In total, 162 students voluntarily completed the application form. Among the 65 students who exchanged several email messages with the author regarding their motivation to participate in the ALL program, 20 learners from diverse backgrounds in terms of majors, gender, and years were selected by the author. The learners were not rewarded for participating in the study because the author wanted to avoid motivating them to learn English merely for a reward. All the participants provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Participants

Learners

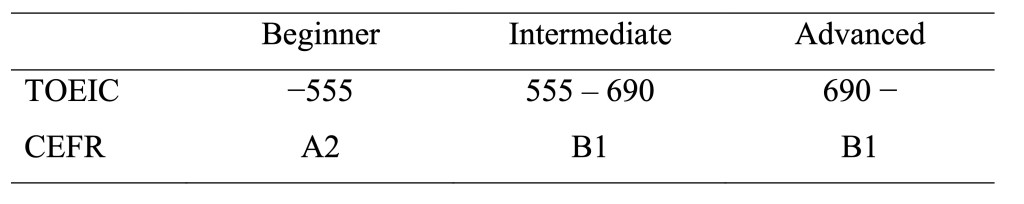

All 20 learners were typical Japanese EFL learners, who had never stayed overseas for more than three months before participating in the ALL program. Based on a placement test conducted at the target university, the 20 learners were classified into one of the following three proficiency levels: beginner, intermediate, or advanced. Table 2 shows the converted score range for the TOEIC® Listening & Reading Test and the classification based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR; Council of Europe, 2001).

Table 2

TOEIC® Listening & Reading Scores and CEFR Categories as an Indication of the Participants’ Proficiency Levels

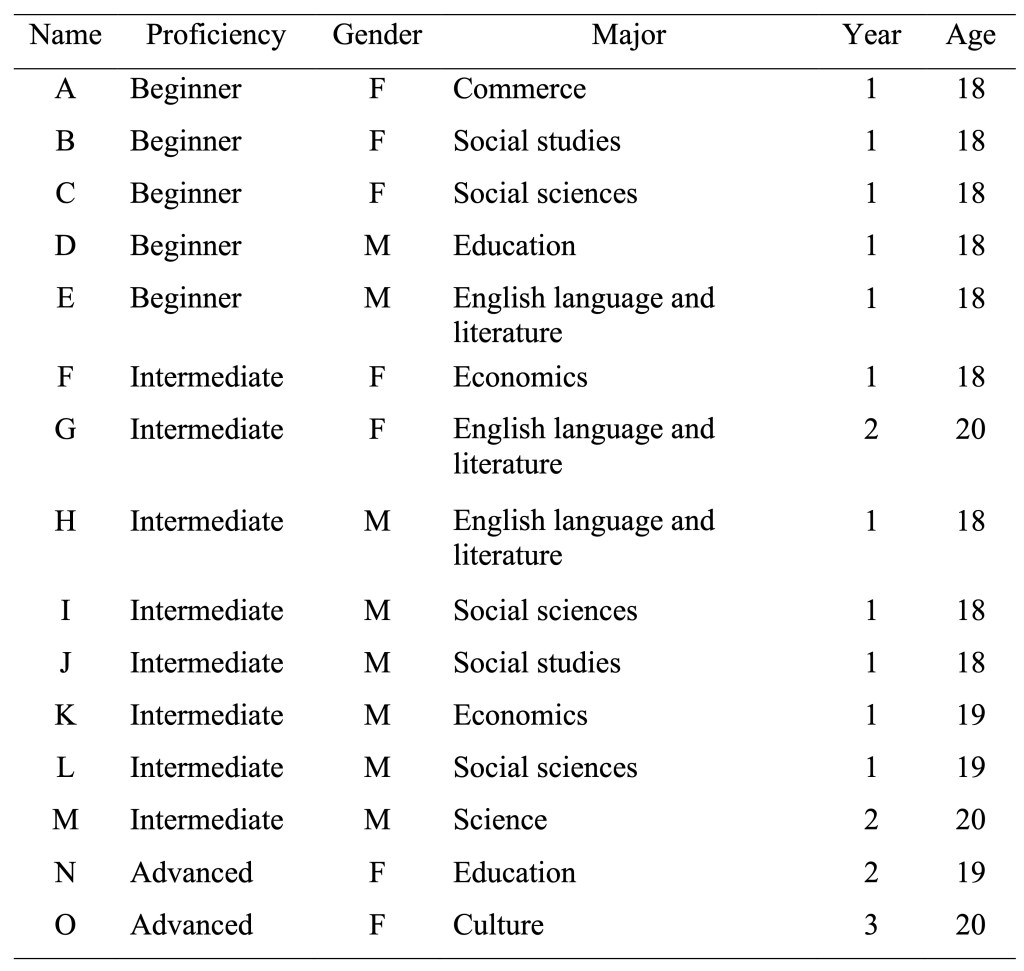

Among the selected 20 learners, 15 completed the entire process of the ALL program, while five dropped out. These five learners may indicate a negative effect of the ALL program. Unfortunately, they did not provide adequate quantitative and qualitative data because they left the program halfway through; therefore, the remaining 15 learners were selected as participants in the present study. Table 3 presents the educational profiles of target learners (participants).

Table 3

Educational Profiles of Target Learners (Participants)

Advisor

The advisor/author obtained an MA in psychology and worked as a psychological counselor. After studying abroad for a year, he changed his major to applied linguistics and English education and completed both another MA and a PhD in education. He developed and conducted the semi-structured ALL program after participating in advisor training programs.

ALL Service

This study was conducted using the semi-structured ALL program, whose main characteristics were introduced above. This section provides other important information. The ALL program was conducted one-on-one in person between individual participants and the advisor, and all advising dialogues and tasks were conducted in Japanese, the first language (L1) of both. To maintain confidentiality, the program was conducted in a dedicated interview room. In each session, the advisor wrote down the main ideas raised in the ongoing dialogues and tasks on a whiteboard in order to share them more easily with each participant.

An additional questionnaire task called Voices from Learners, which was not included in Figure 1, was conducted after the final session. The purpose was to gather participants’ honest opinions and comments to evaluate the ALL program.

Data-Collecting Procedures

Quantitative Data

As the main data, quantitative data were collected for each research question.

Research Question 1. The concept of active engagement can be explained as “a learner’s sincere effort towards his or her language learning” (Yasuda, 2020, p. 93), such as how much time they secure for language learning and the extent to which they objectively view their learning processes with metacognitive abilities (e.g., monitoring learning strategy and material use, and controlling a plan-do-check-action cycle). Thus, four measures were used in this study: average learning time per week, number of days spent learning English, subjective evaluation of how learning time changed before and after the ALL program, and questionnaire scores for metacognitive abilities.

The average learning time and number of days of learning English were calculated based on data written in a Learning Log.6 The subjective evaluation of the change in learning time was investigated based on Voices from Learners on a 10-point scale (1 = the learning time dramatically decreased to 10 = dramatically increased). The intermediate position between 5 and 6 indicated “not changed.” The scores for metacognition were calculated using Yasuda’s (2016) questionnaire, which measures Japanese EFL learners’ metacognitive abilities. For example, the participants responded to the following question: “I organize my time to best accomplish my goals,” on a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = slightly disagree, 4 = slightly agree, 5 = agree, 6 = strongly agree). The higher the score, the higher the respective metacognitive ability they thought they had. This survey was conducted in Questionnaire (pre) and Questionnaire (post) tasks (see Figure 1). The advisor/author asked the participants to complete the questionnaire form with their names because they were to be provided with feedback as part of the ALL program.

Research Question 2. While subjective well-being was defined as “learners’ cognitive evaluations of satisfaction with their language learning” (Yasuda, 2020, p. 37), it can fall into some subcategories based on previous findings (Yasuda, 2020). Thus, the present study used Yasuda’s (2015) questionnaire, which measures Japanese EFL learners’ subjective evaluations of their self-esteem, including their senses of self-actualization, fulfillment, and self-acceptance. For example, the participants responded to the following question: “I feel a sense of fulfillment in English learning,” on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = in-between, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). The higher the score, the better the well-being they thought they had. This survey was conducted in Questionnaire (pre) and Questionnaire (post) tasks (see Figure 1). The advisor/author asked the participants to complete the questionnaire form with their names because they were to be provided with feedback as part of the ALL program.

Research Question 3. This question was explored in a task called Voices from Learners (see also the ALL service section above). Sample question items for this task included the following: “Was the advising program beneficial for your English learning?” “Was the pace of the advising sessions effective?” “Was the ‘Learning Log’ beneficial?” and “Was the amount of homework appropriate?” Participants responded to 12 items on a 10-point scale (1 = unbeneficial/ineffective/inappropriate to 10 = beneficial/effective/appropriate).

While a questionnaire that evaluates a certain education program is often conducted anonymously, the participants completed the form with their names. After discussion with various colleagues, including a professor, English teachers, and graduate students who study applied linguistics and English education, the advisor/author adopted this style for the following two reasons: (1) it could provide accurate data based on the rapport between the advisor/author and the participants and (2) the responses in this task should be linked with each participant’s results of the ALL service for a better discussion of this study.

Qualitative Data

This study used qualitative data to support or sometimes rebut the main quantitative evidence. There were three types of data. The first comprised recorded dialogues from each session between a learner and an advisor, all of which were transcribed. The second comprised the learners’ responses to each task of the ALL program. The third was from a free description area accompanying each question item of Voices from Learners, which asked the respondents to write the reason why they chose a number (i.e., 1 to 10). For example, one participant responds on the 10-point scale to the question, “Was the advising program beneficial for your English learning?” and they might write “(The ALL program) was very useful because my mind about English turned 180 degrees…” as a reason. The learners’ direct statements are shown in italics in double quotation marks in the main text of this article.

Results

Research Question 1

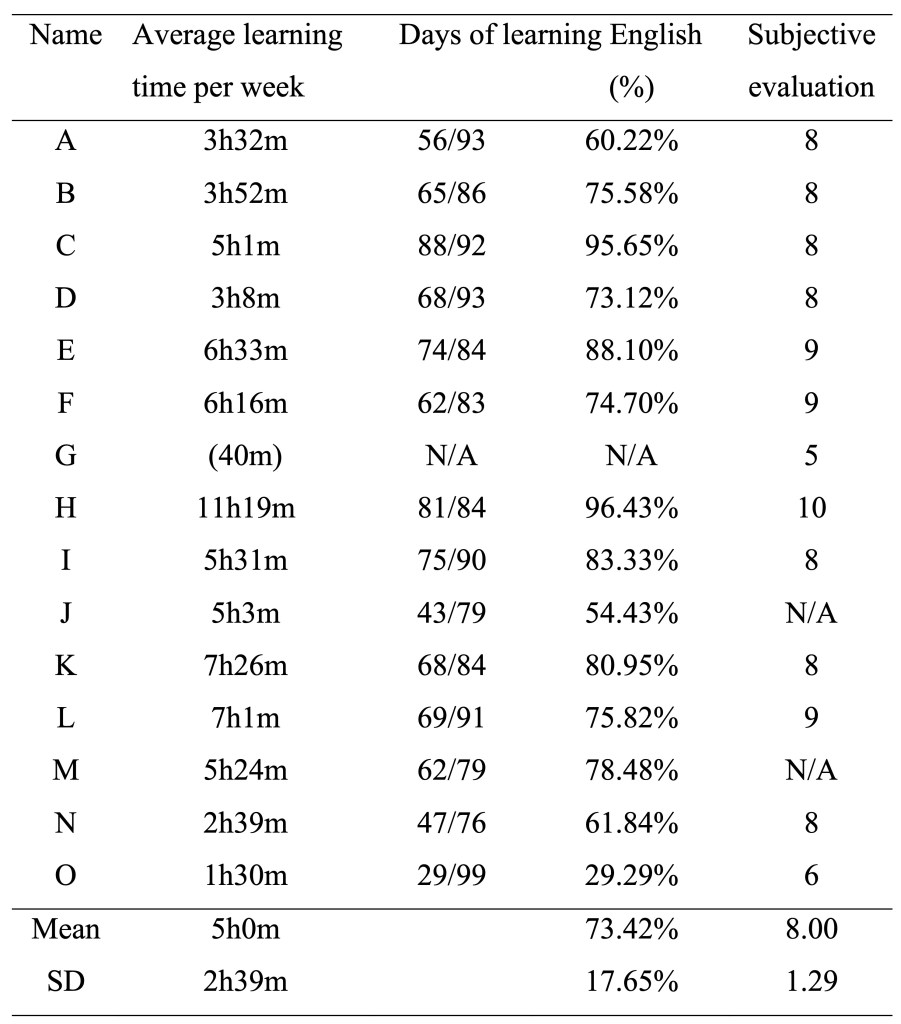

The results for the three indicators of active engagement, with the exception of metacognitive abilities, are shown in Table 4. Regarding the number of days of learning English, as each participant spent a different total number of days completing the ALL program (e.g., 93 and 86 days for learners A and B, respectively), ratios were calculated.

However, some data remain missing. Learner G did not keep her Learning Log well because she was not very motivated to learn English. Her stagnation with the Learning Log negatively affected the fidelity of the data on the average learning time and days of learning English as they were calculated from the Learning Log. Nevertheless, her data remain important in discussing the effects of the ALL program because she obviously had much less average learning time than the other participants. Therefore, this study uses her calculated average time, although it partially suffers from the fidelity issue (i.e., bracketed 40 minutes in Table 4). Meanwhile, cells for days of learning English remain N/A, considering the low fidelity. Learners J and M did not participate in Voices from Learners. Thus, the cells used for the subjective evaluation of the change in learning time before and after the ALL program in Table 4 include two N/As. The means and standard deviations (SDs) in Table 4 do not include N/As.

Table 4

Average Learning Time per Week, Days of Learning English, and Subjective Evaluation of the Change in Learning Time

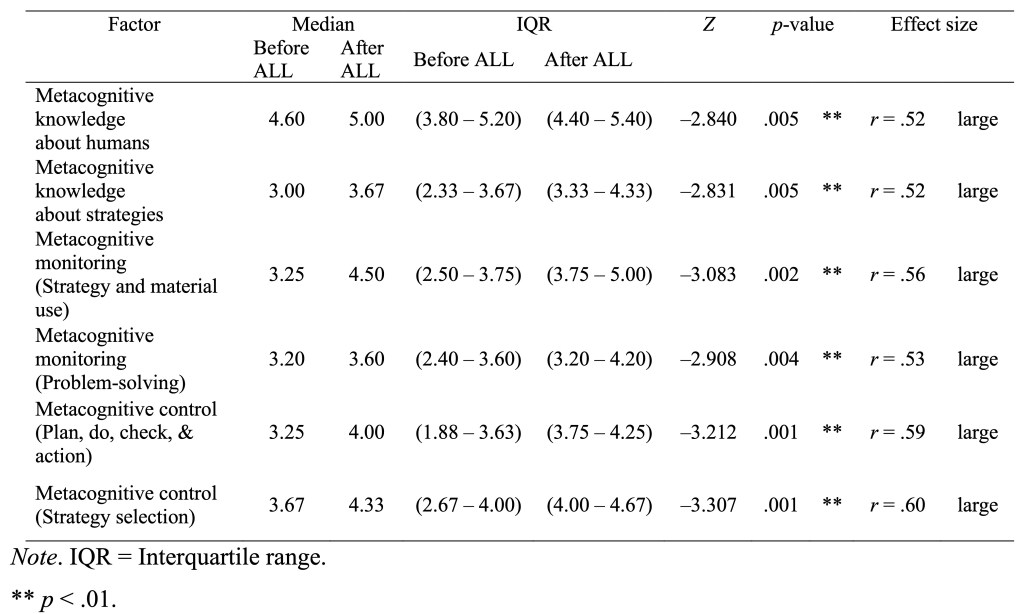

Table 5 shows the results of the participants’ metacognitive abilities measured on the 6-point scale questionnaire (Yasuda, 2016). The medians for all factors were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.7 The results showed significant before-after increases at the 1% level for the semi-structured ALL program, with large effect sizes for all six questionnaire factors.

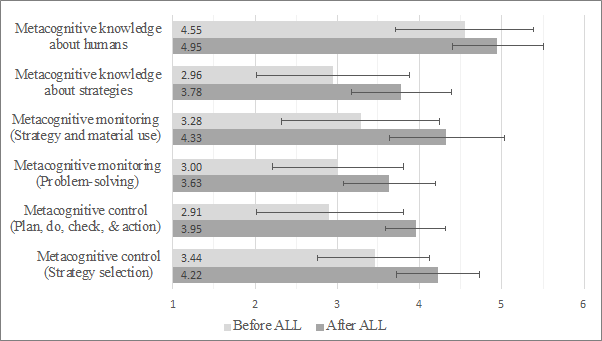

Figure 4 shows two important findings regarding the means and SDs of the six factors. First, while all the mean scores calculated before the ALL program, except for metacognitive knowledge about humans, fell below the central value of the questionnaire (i.e., 3.50 on the 6-point scale), they exceeded the central value after the program. Based on the scale anchors (i.e., 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = slightly disagree, 4 = slightly agree, 5 = agree, 6 = strongly agree), the participants evaluated themselves negatively before the program, putting their marks on the disagree side, and positively evaluated themselves after the program, that is, on the agree side. Second, the SDs calculated for the post-ALL questionnaire were much lower than those calculated for the pre-ALL questionnaire. These two results indicate that while the participants showed a wide range of metacognitive abilities at a lower level before the program, they obtained higher levels with smaller variability after the program. In other words, their metacognitive abilities improved and remained homogeneous at higher levels thanks to the ALL program.

Table 5

Results of the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test for Metacognitive Abilities

Figure 4

Means and Standard Deviations for Metacognitive Abilities

Note. Bars with numbers represent means and error bars indicate SDs.

As mentioned, active engagement is indispensable for achieving true subjective well-being. Therefore, learners with unsuccessful active engagement may have to be separated for subsequent analyses of subjective well-being. It is relatively difficult to determine a criterion that separates successful and unsuccessful learners because learners differ in various aspects such as learning goals and environments. However, judging from the first three indicators shown in Table 4, learners G, N, and O can be regarded as partially unsuccessful. First, they studied English for fewer than three hours per week on average. Second, learners N and O showed relatively low rates in their days of learning English, and learner G had N/A values because of her demotivation from learning English. Third, learners G and O realized that they could not appreciably increase the time they spent learning English. While learner N regarded her learning time as having increased, providing an 8 for the subjective evaluation of its change, she also realized, according to her qualitative data, that she did not spend sufficient time, particularly at the beginning of the ALL program.

Meanwhile, based on the qualitative data, the three learners were still involved in each English learning aspect in different ways. For example, they tried self-monitoring why they lacked the motivation to learn English. Consequently, learner N successfully found a new, more intrinsic motivation that could replace the extrinsic one on which she relied that did not work sufficiently at the beginning of the program, and learner G found herself more interested in a subject other than English. These results indicate that although they did not have sufficient learning time, they tried to face their English learning, which meant that the three learners were still involved in the learning processes in their own ways. Therefore, their results of subjective well-being will be valid whether their scores are high or low. Accordingly, the present study analyzed the data of all 15 participants in the subsequent sections, which produced the results for subjective well-being.

Research Question 2

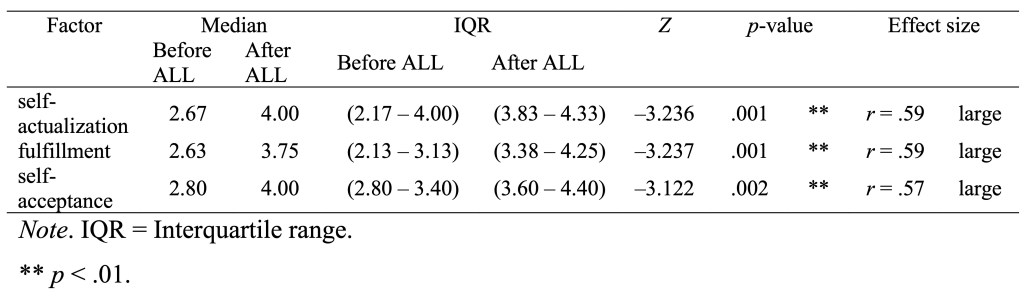

The present quantitative analysis used Yasuda’s (2015) 5-point scale questionnaire to investigate the effects of the semi-structured ALL program on learners’ subjective well-being. The medians for all the factors were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.7 Table 6 shows significant before-after increases at the 1% level for the program, with large effect sizes in all three factors of the questionnaire.

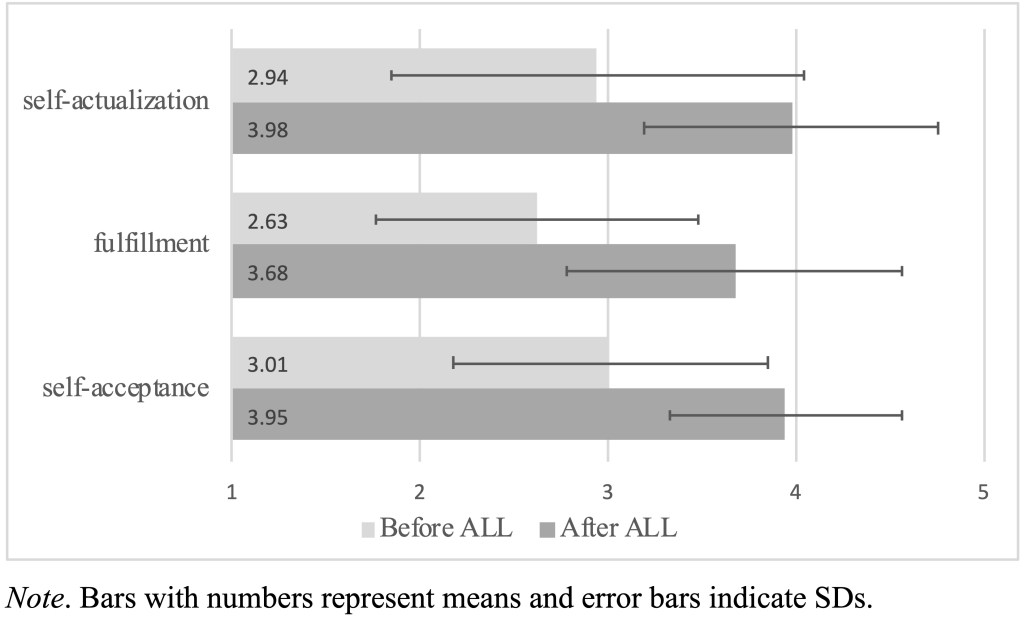

In addition, Figure 5 shows two important findings regarding the means and SDs, similar to the results for Research Question 1. First, the mean scores for self-actualization and fulfillment calculated before the ALL program fell below the central value of the questionnaire (i.e., 3.00 on the 5-point scale), while that for self-acceptance slightly exceeded the central value. Thus, participants evaluated their subjective well-being as nearly neutral or slightly negative. However, these scores far exceeded the central values after the ALL program. Based on the anchors (i.e., 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = in-between, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree), the participants positively evaluated their well-being. Second, the SDs for self-actualization and self-acceptance calculated after the ALL program were much lower than those before the program. These two results indicate that while the participants showed a wide range of ratings for subjective well-being at a lower level before the program, they obtained higher levels with smaller variability after the program. In other words, part of their well-being improved and uniformly stayed at higher levels thanks to the ALL program, although the post-ALL calculation for fulfillment still showed as large an SD as the pre-ALL one.

Table 6

Results of the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test for Subjective Well-Being

Figure 5

Means and Standard Deviations for Subjective Well-Being

Note. Bars with numbers represent means and error bars indicate SDs.

Research Question 3

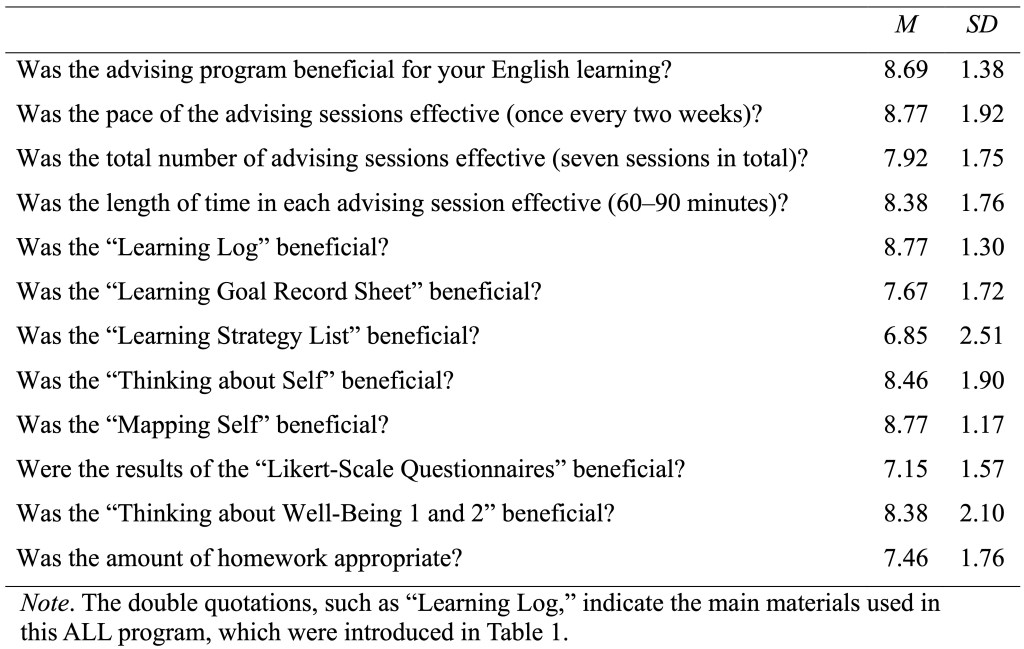

For this research question, the participants answered 12 questions in the task, Voices from Learners. The results suffer from missing data because learners J and M did not participate in this process. Table 7 thus shows the means and SDs of the responses to the 12 question items of the remaining 13 participants.

Table 7

Results for the Usefulness of the Semi-Structured ALL Program

Note. The double quotations, such as “Learning Log,” indicate the main materials used in this ALL program, which were introduced in Table 1.

The mean scores for seven of the 12 questions exceeded 8.00, indicating that the learners were satisfied with these aspects of the semi-structured program. However, the remaining five question items provided an average rating of less than 8.00, indicating that the program still required further improvement.

Discussion

Research Question 1

This study used four measures to represent participants’ active engagement: average learning time per week, number of days spent learning English, subjective evaluation of how learning time changed, and questionnaire scores for metacognitive abilities.

As mentioned in the results section, 12 learners successfully attained their active engagement judging from the first three measures. Based on the qualitative data, the remaining three learners (i.e., G, N, and O) were involved in English learning in different ways. Thus, for a better understanding, this section discusses the first three measures, separating the 12 learners from the other three. It then discusses metacognitive abilities by grouping all 15 participants.

For the 12 learners, the first point is their weekly average learning time, which indicates 5 hours 51 minutes, ranging from 3 hours 8 minutes to 11 hours 19 minutes.6 According to Matsumura’s (2009) rough calculation for the Japanese EFL context, a weekly average of 7 hours, except for enrolled courses, is required to reach an intermediate level of English that enables learners to have an appropriate conversation, understand newspapers with a dictionary, and watch TV programs of interest.8 Thus, the average time achieved through the semi-structured ALL program may not necessarily be sufficient.9 Meanwhile, 10 of the 12 learners gave a rating higher than 8 on the change in learning time (no data were obtained from the other two participants). This indicates that their learning time increased after the ALL program began. Therefore, while learners successfully increased their learning time through the ALL program, they should spend more time to acquire an intermediate level of proficiency.

The second point focuses on the days of learning English. Although two learners showed low percentages in this indicator (Learners A and J), the lowest rate among the remaining 10 learners was 73.12%. Learner A had a lower rate because she did not study English at all when she needed to spend much time preparing for the university’s end-of-semester examinations. After excluding this period, the rate increased to 74.67%. However, the ALL program should have encouraged her to continue learning English even during the examination period. While learner J tended to spend a considerable amount of time studying English at once, there were many days when he did not study English at all. Indeed, his average weekly learning time was more than 5 hours. Although past research has not yet clearly demonstrated which is better, massed or spaced learning, because various factors are at play (e.g., Miles, 2014; Suzuki & Hanzawa, 2022), the ALL service should have at least provided an option that encouraged him to undertake spaced learning.

The following discussion relates to the three participants who were less successful in these three measurements, focusing mainly on qualitative rather than quantitative evidence. Learner G, who had enrolled in an English-related major, did not have sufficient time to learn English; however, she became interested in educational psychology instead. Indeed, whereas she thought that she had to learn English because she was still studying an English-related major, she had conflicted feelings about these two fields. Therefore, she was not very motivated to learn English. Meanwhile, learners N and O seemed to suffer from an adolescent problem that caused them identity confusion (Erikson, 1968, 1982), or they did not know exactly what they could or should do then and in the future.10 Therefore, since they could not find an intrinsic reason for learning English, they seemed demotivated. Nevertheless, these three learners were still involved in learning English because they were trying to face their own problems. This renders the results for their subjective well-being reliable, regardless of whether the scores are high or low, as discussed in the next section.

Based on the analysis of all 15 participants, their metacognitive abilities improved after the semi-structured ALL program (Table 5). Furthermore, while the participants negatively evaluated themselves before the program, with a mean score of less than 3.5 on the 6-point scale, the evaluation became positive after the program, with an average of over 3.5 for all six factors except metacognitive knowledge about humans (Figure 4). As some question items in this excluded factor specifically measured metacognitive knowledge about the learner (e.g., “I understand my intellectual strengths and weaknesses”), the participants probably had such knowledge before the ALL program began (M = 4.55). For the other five factors, however, they did not necessarily have sufficient knowledge before the ALL program (e.g., “I know what kind of information is most important to learn”), and neither did they have adequate experiences in metacognitive monitoring nor controlling (e.g., “I ask myself questions about the material before I begin” or “I set specific goals before I begin a task”). Indeed, some statements in the ALL dialogues provide qualitative evidence: “(Thanks to the ALL service,) when I choose a learning strategy or a learning material, I can now choose the best one from multiple choices” (Learner K). “It was very meaningful to have an opportunity to think about my learning goals (through the ALL program) … consequently, I can now deeply think about where to go and how to step forward” (Learner L).

In conclusion, while there are some individual differences among learners, the semi-structured ALL program, overall, contributes to their active engagement in language learning.

Research Question 2

Based on the analysis of all 15 participants, their subjective well-being improved after the semi-structured ALL program (Table 6). Furthermore, although the participants evaluated themselves as nearly neutral or slightly negative before the program, with a mean score of below (or exactly) 3.0 on the 5-point scale, their evaluation became positive after the program, with an average of over 3.0 for all three factors (Figure 5). Although it often depends on each individual participant which point of the ALL program has an impact on which aspect of the three well-being factors, some common influences on most participants were found, as shown below.

Some question items on self-actualization include such words as “dream,” “goal,” and “what you want to do.” Thus, goal-setting tasks, such as Learning Goal (Long- & Medium-Term) and Learning Goal (Short-Term) may have encouraged their self-actualization processes. For example, according to the qualitative data, some learners said: “Because my goal became obvious thanks to the long-term goal task, I clearly knew what I should do” (Learner F). “When I was in high school, I did not really like learning English … however, I like studying it, now that I can do it for my own learning goal” (Learner L).

Among the various factors that influence a learner’s sense of fulfillment, one of the most powerful is language learning strategies. Generally, Japanese EFL learners have insufficient knowledge of learning strategies or do not use them frequently (Yasuda, 2020). However, this study’s participants succeeded in identifying various strategies through multiple tasks, such as Learning Goal (Short-Term) and Reviewing Learning Strategies, and using these strategies in daily learning processes. This fact led them to a sense of “comfortable,” “satisfaction,” and “fulfillment” in English learning. The participants’ statements from the qualitative data include the following: “I could successfully find some enjoyable learning strategies that allowed me to use my favorite things, such as fiction and music…I realized that I could see them as English learning (although, at first, I thought I definitely needed drill-like studying for English learning)” (Learner B). “What the ALL program changed in me the most is that I think I am now good at choosing learning strategies…The reason that I have recently felt satisfied with English learning is that I think I have actively tackled it. Instead of merely doing the assignment allocated to me, I now think about my own learning goals and strategies” (Learner C).

The following focuses on self-acceptance, which includes such keywords as “an English learning of my own” and “accepting my individual characteristics.” The semi-structured ALL program may have encouraged feelings of self-acceptance through multiple processes. While it provided opportunities for learners to think about their own learning goals and strategies in the central topics, it also encouraged them to monitor and control peripheral topics, such as their personality and lifestyle (see Figure 1). These processes may have successfully led learners toward self-acceptance. Indeed, data on Thinking about Well-Being 2, a task that allows learners to take a comprehensive view of both central and peripheral topics, showed that each learner achieved their own positive narrative differently. Sample statements of the qualitative evidence are as follows: “My most important key point is self-satisfaction, such as ‘I have finally achieved here!’” (Learner F). “Intellectual curiosity is among the most significant motivational influences for my English learning” (Learner I). “Although I have long wanted to join a long-term study abroad program, I now feel that I may be more satisfied when I travel around various countries than when I stay in only one country” (Learner N).

Overall, although large individual differences remain among learners, the semi-structured ALL program contributes to their subjective well-being in language learning.

Research Question 3

The 12 questions used to investigate the third research question are divided into four groups to make its discussion more understandable. The first group comprises only one question that investigated the overall usefulness of the semi-structured ALL program: “Was the advising program beneficial for your English learning?” For this question, the participants responded with a high rating (M = 8.69) and provided many positive evaluations in the questionnaire’s free-description area as qualitative evidence: “I became conscious of how my current learning strategies functioned” (Learner E). “Although I did not know how to learn English, I organized (related information) by myself (through the ALL program) and successfully produced my own English learning program” (Learner D). “(The ALL program) was very useful because my mind about English turned 180 degrees as I have successfully obtained objective views on my learning process” (Learner H). “I could revise the learning strategies I had used and find some new ones” (Learner K). “I have never had such an experience as I think deeply about myself day and night” (Learner N). “The ALL program was very useful because I did not know how to start my English learning at all” (Learner L).

The second group comprises the following questions that evaluated the overall structure of the program: “Was the pace of the advising sessions effective (once every two weeks)?” “Was the total number of advising sessions effective (seven sessions in total)?” “Was the length of time in each advising session effective (60–90 minutes)?” The participants rated pace and length of time relatively high averages of 8.77 and 8.38, respectively. However, they provided a slightly lower average for the total number of sessions (M = 7.92). Most participants who rated lower thought that the program should have more sessions. For example, they said: “I am wondering how I would change if I had more sessions” (Learner L). “It would be helpful if the program had more sessions” (Learner O). “It is difficult to adapt myself to a long summer vacation because the program finished at its beginning”(Learner E). This semi-structured ALL program, one of whose main goals is to reduce the burden on both advisors and learners, certainly had a shorter length than other ALL practices (i.e., seven sessions in total). One solution is for participants to have the option to take further sessions after the original program ends. After completing the seven sessions, they can autonomously decide whether to take further optional sessions. This would reduce the burden on advisors, because some learners would stop at the seventh session of the original program. Many more learners can then enjoy the benefits of the ALL program without having to wait.

The third group comprises seven question items for each task material: from “Was the ‘Learning Log’ beneficial?” through “Was the ‘Thinking about Well-Being 1 and 2’ beneficial?” in Table 7. A serious limitation is that these questions ask about the benefit of each task material instead of each task itself (see Table 1), whereas this study seeks to establish the usefulness of each task, which is an important part of the semi-structured ALL program. A sample item is, “Was the ‘Learning Goal Record Sheet’ beneficial?” instead of Learning Goal (Long- & Medium-Term) or Learning Goal (Short-Term). This is a result of an effort to reduce the number of questions that would become a burden on the participants. Nevertheless, four question items almost directly measure the benefit of tasks because the usefulness of those materials mostly means that of the corresponding tasks (i.e., Learning Log, Thinking about Self, Mapping Self, and Thinking about Well-Being 1 and 2). The other three do not directly instrument the usefulness of each task (i.e., Learning Goal Record Sheet, Learning Strategy List, and Likert-Scale Questionnaires). Regarding the former, the participants provided relatively high evaluations (i.e., M = 8.77, 8.46, 8.77, and 8.38, respectively), indicating that these tasks are beneficial. However, they tended to assign lower evaluations to the latter question items (i.e., M = 7.67, 6.85, and 7.15, respectively), which are explained as follows based on the participants’ free descriptions. Regarding the Learning Goal Record Sheet, they said, for example: “Dialogues (for learning goals) were more than sufficient” (Learner B). “Because I had dialogues (for learning goals) once in two weeks (in each session), I did not think that I needed to write them down on the sheet” (Learner L). This indicates that while dialogues and tasks for learning goals were useful, the Learning Goal Record Sheet that allowed them to write down the goals was not indispensable. Regarding the Learning Strategy List, the free descriptions by the participants who provided below-average rates contained the following: “I did not refer to it very often”(Learners I and O). “It worked only as a reference”(Learner C). “Although I sometimes referred to it, in most cases I determined the strategy by myself (without using it)” (Learner E). This means that the low average score was not caused by the task of Reviewing Learning Strategies, but by a lack of opportunities to access the list during the semi-structured ALL program. Therefore, while some tasks are considered sufficiently beneficial, the result scores for the others remain an approximate indication owing to measurement limitations.

The fourth group comprises the following question: “Was the amount of homework appropriate?” As the participants were required to do homework for each task, the question investigated the appropriateness of the amount. The mean score of 7.46 indicates that some learners were not satisfied. According to the free descriptions, while most learners were satisfied, some felt that there was too much homework, especially when they were busy. For example, they said: “I did not necessarily think that was too much, but it depends” (Learner L). “I felt that it was slightly too much when I was busy with class assignments and examinations” (Learner E). None of the participants thought that the amount was too small. Therefore, the semi-structured approach may better adjust the amount of homework in accordance with each learner’s situation.

Based on these findings, although the semi-structured ALL program includes some aspects that need to be modified, the participants generally evaluated the program as useful.

Conclusions and Future Directions

This study demonstrates that a semi-structured ALL program that includes multiple beneficial and effective functions successfully leads Japanese EFL learners toward active engagement and well-being. Considering the situations that called for the development of this program, now that its effects have been demonstrated, it will play an important role in the dissemination of ALL. Finally, this study introduces four major limitations for future research.

First, some data are missing. Learner G hesitated to keep her Learning Log because she was ashamed of her demotivation to learn English during the ALL program. Therefore, cells for days of learning English for the same learner contained N/As in Table 4, considering the low fidelity of the data. To solve this problem, researchers should require participants to keep a Learning Log. This would help ensure accurate learning data.

Learners J and M did not hand in their Voices from Learners. Unfortunately, they did not provide any reason to the advisor/author. Thus, the cells for the subjective evaluation of changes in learning time included two N/As (Table 4). Moreover, the discussion of Research Question 3, based on the results of Voices from Learners, relied on the dataset of the remaining 13 learners. Although the present study gave participants a few weeks to complete Voices from Learners after the last ALL session, future research should ensure that learners do so in the last session to collect their responses immediately.

Second, five learners dropped out of the ALL program. Although this could be related to the usefulness of the program, there is no clear evidence to this effect. Two learners did not attend the second session. While one learner declined further participation by email, the other was absent without notice. It seems that the data from these two cases should not be considered sufficient evidence to assess the usefulness of the program, as they attended only the first session. The remaining three learners stopped attending after the third or fourth session. One learner declined to participate via email, stating that he was not disappointed with the ALL program. However, the other two learners, who did not provide any reasons for dropping out, might have had doubts about the program. Unfortunately, although the semi-structured program was probably not very helpful to several participants, such as those mentioned above, there was no clear evidence. As data from participants who drop out are invaluable, they should be collected in future research. For example, another investigator, ideally one not involved in the ALL program, should interview such learners.

Third, a more sophisticated qualitative analysis is required because the analyses in this study did not show all the valuable individual participants’ episodes. For example, judging from the days of learning English in Table 4, learners C and H successfully developed habituation to English learning, which is an important aspect in the improvement of English skills. However, their qualitative data showed that while they could have been actively engaged in the learning process that they could go through alone, they remained hesitant to engage in a process that was accompanied by other people (e.g., oral communication). Although Yasuda (2019) has already provided some qualitative results, further analysis based on another dataset is required.

Fourth, relationships between the participants and the advisor/author may have affected the results of the study. Since they participated in seven one-on-one sessions and spent 60–90 minutes for each, perhaps they have built significant rapport with the advisor. In addition, all the data were collected with the names of the participants as stated above. While this does not seriously negate the data of this study because the participants seemed to deliver their negative opinions on the ALL program without hesitation, as shown in the data above, future research possibly needs to take measures for this issue. For example, another investigator, ideally one not involved in the ALL program, may better collect data.

Lastly, but most importantly, as the semi-structured ALL program has been developed to disseminate ALL services more smoothly, it has never been intended to deny an unstructured ALL with a longer period of sessions. Thus, advisors should choose to conduct either a structured or unstructured version of ALL, prioritizing language learners’ benefits.

Notes

- The semi-structured ALL program was developed as part of the author’s doctoral dissertation project (Yasuda, 2020).

- The defined active engagement may not necessarily be a prerequisite for true subjective well-being. For example, when a learner successfully obtains insights into why they are not motivated to learn English, they may find themselves more interested in another subject than English. Such a process could also serve as a way to achieve true well-being. Therefore, while active engagement is important for true subjective well-being, there are several ways to achieve it.

- For readability of the text, the names of each task and its material are capitalized in the first letters of major words.

- Kato and Mynard (2016) listed many tools that could function as new tasks in the semi-structured program.

- The author’s doctoral dissertation also examined the effects of the same semi-structured program on Japanese EFL learners. This study introduces some of the research results, with additional new data.

- While the course hours for English-related classes officially taken by the participants were not counted, voluntary preparations and reviews of the classes were included as part of spontaneous language learning.

- Because this study targeted 15 participants, the data did not necessarily satisfy the assumptions of parametric tests. Thus, the study used a non-parametric test, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

- All participants in this study began serious English learning in their first year of junior high school. According to Matsumura (2009), compulsory classes over eight years (i.e., junior and senior high schools and the first and second years in university) add up to approximately 1,120 hours of English learning in Japan. Meanwhile, more than 4,000 hours are required for Japanese learners of English to reach the intermediate level. This means that they are still required to spend at least 2,880 hours outside class. Therefore, they need to spend approximately one hour a day on English learning, excluding compulsory classes (i.e., approximately seven hours per week) during these eight years. Although there are many sources on learning time, they do not necessarily reach agreement. Therefore, to avoid unnecessary confusion, this study used a single source that appropriately considered Japanese EFL settings.

- The advisor in this ALL program did not specify the length of time that the learners should spend learning English.

- This problem can be interpreted as Erikson’s (1968, 1982) identity confusion. Please see Yasuda (2020) for a detailed discussion.

Notes on the Contributor

Toshinori Yasuda is an associate professor at Tokyo University of Science, Japan. He worked as a certified psychological counselor after receiving his first MA in psychology, following which he also received his second M.A. and a Ph.D. in English education. His current research interests lie in the fields of applied linguistics and psychology, including ALL.

References

Carson, L., & Mynard, J. (2012). Introduction. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 3–25). Pearson Education Limited.

Council of Europe (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge University Press.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Diener, E. (2012). New findings and future directions for subjective well-being research. American Psychologist, 67(8), 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029541

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9–42). Multilingual Matters.

Dörnyei, Z. (2010). Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration, and processing (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Ehrman, M., & Leaver, B. L. (2002). Ehrman & Leaver Learning Style Questionnaire version 2.0. www.cambridge.org/us/download_file/192218

Erikson, E. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. W. W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. (1982). The life cycle completed. W. W. Norton & Company.

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

Japan Association for Self-Access Learning (2022, September). Language Learning Spaces Registry. https://jasalorg.com/lls-registry/

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge.

Matsumura, M. (2009). Eigo kyoiku wo shiru 58 no kagi [Fifty-eight keys to know English education]. Taishukan-shoten.

Miles, S. W. (2014). Spaced vs. massed distribution instruction for L2 grammar learning. System, 42, 412–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.01.014

Namikawa, T., Tani, I., Wakita, T., Kumagai, R., Nakane, A., & Noguchi, H. (2012). Big five shakudo tanshukuban no kaihatsu to shinraisei to datōsei no kentō [Development of a short form of the Japanese Big-Five Scale, and a test of its reliability and validity]. The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 83(2), 91–99. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.83.91

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Newbury House Publishers.

Reinders, H. (2008). The what, why, and how of language advising. MEXTESOL Journal, 32(2), 13–22.

Sannomiya, M. (2008). Metaninchi-kenkyū no haikei to igi [The backgrounds and purposes of research for metacognition]. In M. Sannomiya (Ed.), Metaninchi: Gakusyū wo sasaeru kōji-ninchi-kinō (pp. 1–16). Kitaohji Shobō.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A new understanding of happiness and well-being and how to achieve them. Nicholas Brealey.

Suzuki, Y., & Hanzawa, K. (2022). Massed task repetition is a double-edged sword for fluency development: An EFL classroom study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 44(2), 536–561. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263121000358

Weaver, C. (2010). Japanese university students’ willingness to use English with different interlocutors (Publication No. 305227822) [Doctoral dissertation, Temple University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Yasuda, T. (2015). Nihonjin eigo gakushūsha no jison kanjō wo takameru tameni: Kiban to naru shakudo no sakusei [To raise self-esteem in Japanese learners of English: Preliminary design of a new rating scale]. In K. Shibuya, T. Nomura, & S. Doi (Eds.), Vantage points of English linguistics, literature and education (pp. 144–156). DTP Publishing.

Yasuda, T. (2016). Nihonjin eigo gakushūsha wo taishō to shita metaninchi shakudo no kiban sakusei [A preliminary design of a Metacognitive Awareness Inventory for Japanese learners of English]. KATE Journal, 30, 57–70. https://doi.org/10.20806/katejournal.30.0_57

Yasuda, T. (2019, March 2). Gengo gakushū adobaijingu wo tōshita gakushū no shūkanka: Tayō na yōin ni okeru fukuzatsu na kankeisei wo kōryo shite [Habituation of learning through advising in language learning: Considering complex relations among various factors: Paper presentation]. The 28th annual conference of the Japan Association of English Linguistics and Literature, Tokyo, Japan.

Yasuda, T. (2020). Advising in language learning for Japanese EFL learners: A theoretical framework, a semi-structured program, and practical principles for learners’ well-being [Doctoral dissertation, Waseda University]. Waseda University Repository. http://hdl.handle.net/2065/00074143