Ryo Moriya, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0109-7444

Moriya, R. (2023). Learner perezhivanie and mutual advisor-advisee development through advising: A longitudinal case study of JSL learner. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(3), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.37237/140304

Abstract

This study analyzes the perezhivanie of one second-language learner (Chinese L1) who studied Japanese as a second language and engaged in her learning experience in a Japanese cultural setting through yearlong language advisory sessions. Perezhivanie, a Russian term, and a Vygotskian concept, is employed in the study to observe L2 learner development and to capture the bidirectional influences of the characteristics of agency and the environment. The data analyzed come from two sources: (a) our written correspondence, including email exchanges, from before the study was conducted and (b) audio-recorded data of six face-to-face/ online advisory sessions on a bimonthly basis with a particular focus on her perezhivanie. By applying perezhivanie as a unit of analysis that avoids the cognition-or-emotion and person-or-context dichotomies, the findings revealed the developmental processes of one L2 learner and focused on how both advisor and advisee mutually transform the specific social situation into a social situation of collectividual development through yearlong advisory sessions. Notably, the participant evaluated her original experience negatively at first, but eventually, she learned to value the failure and reinterpreted the initial experience. The significance of the study is to contribute to describing the detailed case of learner perezhivanie with a particular focus on entrance exams in East Asian sociocultural settings.

Keywords: perezhivanie, advising in language learning, sociocultural theory, Japanese as a second language learner, longitudinal study

This study analyzes the perezhivanie of a second language learner (Chinese L1) who studied Japanese as a second language and engaged in her learning experience in a Japanese cultural setting through yearlong language advisory sessions. Advising in Language Learning (ALL) is an educational practice in which advisors emphasize collaborative dialogue with learners and encourage their autonomy and agency (Mozzon-McPherson, 2012; Mynard & Kato, 2022). The learner-centered view of education has been popular for some time, and an increasing number of institutions in higher education are introducing advising and self-access centers in line with this trend (Benson, 2011; Little et al., 2017; Mynard, 2020). Behind the discussion of learner autonomy and agency is not only the aforementioned learner-centered view of education but also the socio-historical expansion of learning environments and learning resources due to the diversification of learners and the development of information technology (e.g., Kjisik et al., 2009; Murray & Lamb, 2018; Mynard, 2019). Learning theories such as lifelong learning and sociocultural approaches (including an ecological approach and sociocultural theory) are used as the theoretical background (e.g., Kato & Mynard, 2016; Shelton-Strong & Tassinari, 2022).

Sociocultural theory (SCT) has developed in second language acquisition and foreign language education based on Vygotsky’s ideas. It embraces several key concepts, such as Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) and mediation (Lantolf et al., 2020), as well as foregrounding praxis (i.e., fusion of theory and practice; Lantolf & Poehner, 2014) to reveal learner development and cause “artificial development” through education (Vygotsky, 1997b). To summarize briefly, SCT says that individual agents are connected to the outside world through mediating interactants, including interlocutors and artifacts, and that they develop from their social and cultural interactions with the outside world (Lantolf et al., 2018). Given this premise, we can understand the commonalities with advising. In fact, through dialogue with an advisor and the advising tools that facilitate the dialogue, learners reflect on their past learning and their present selves, then consider how to appropriately move toward future goals. This makes SCT a vital theory for advising, which emphasizes dialogue and the surrounding learning environment.

Although the term “praxis” was used above, SCT is grounded in the philosophy of dialectically confronting what is often viewed as dichotomous (Poehner, 2016), such as theory and practice, instruction and assessment, and agent and others (although these concepts are not necessarily oppositional). The dialectical nature of these concepts is why they are reflected in various concepts such as praxis (theory and practice) and Dynamic Assessment (instruction and assessment) in SCT (Lantolf & Poehner, 2023). This paper particularly focuses on the concept of perezhivanie, which dialectically captures cognition and emotion and has the potential to link advising and learner experience. In simple terms, perezhivanie can be described as a concept that sees the agent as a dialectical unity of “cognition and emotion” and the environment as an integrated unity, using the relationship between the two to reveal the development of the agent (Fleer et al., 2017). These concepts should be viewed as inseparable and complementary, not separately. Thus, advising would greatly benefit from a perezhivanie perspective not only in terms of the cognition and emotions of the individual learner but also the multilayered relationships between learner and advisor, both in- and out-of-session contexts. The first section of this paper introduces the previous studies on learner perezhivanie and, from an SCT perspective, situates how its advisory sessions will be used here. The methodology is discussed in the following section, and the final section presents and discusses the gathered data.

Literature Review

Learner Perezhivanie in Sociocultural Theory

In SCT, human consciousness (psyche) is at the heart of investigation, and perezhivanie plays a vital role in it (Lantolf et al., 2018). Reflecting dialectical materialism as ontoepistemological, teleological, and axiological assumptions (Poehner, 2016), SCT foregrounds dialectic praxis as the form of iterative interactions between theory and practice to move beyond the existing thesis-antithesis relationship (Lantolf & Poehner, 2014). Relevant to this dialectical logic operating SCT, perezhivanie should also be understood dialectically (Lantolf & Swain, 2020). There are two dialectics underlying perezhivanie; one is the synthetic concept overcoming the cognitive and emotional divide “for a more holistic view of consciousness” (Mok, 2017, p. 26), and the other is the overarching concept that captures the agent-environment relationship to allow “more adequate theorization about how the individual and the environment are represented as a complex, dynamic, and rich unity in human mental development” (Mok, 2015, p. 151). For the first dialectics, the emotional-cognitive division results from Cartesian dualism, and such an either-or view is exactly what Vygotsky (1997a) strongly rejected because, according to the general genetic law of cultural development (Vygotsky, 1997b), our cognitive and emotional development firstly occurs at the interpsychological level and then occurs at the intrapsychological level. Likewise, Swain et al. (2015) mention that “the external-to-internal trajectory of thought was also true of Vygotsky’s view of the trajectory of emotion” (p. 79) since affective processes permeate thought and actions (Vygotsky, 1986). For the second dialectics, considering the historicity of individual agents (history-in-person processes; Donato & Davin, 2018), the constellation of mediating interactants, including artifacts and interlocutors, must be seen because tracing the history of the individuals (including mediating interactants) enables us to develop a fuller picture of how the present came to be (Lantolf, 2017). In fact, Stone and Hart (2019) discuss the dialectical relationship between individuals and collective to the regulatory processes in learning. To illustrate the mutual cognitive-emotional and agent-environment relationships, Vygotsky (1994) used an example of three children abused by their parent, where the seemingly same situation caused different evaluations among the children, resulting from their past experiences and ultimately influenced, through refraction, their various interpretations of the event.

From a learner perspective, there are fewer studies about L2 learning than on L2 teacher perezhivanie (Johnson & Glombek, 2016). Poehner and Swain (2016) illustrate the emotive-cognitive dialectic unity by one learner through joint engagement between mediator and learners, presenting the data obtained during the collaborative writing revision process called the Mediated Development program implemented by one American university. Mochizuki (2019) applies perezhivanie to investigate students’ lived experiences in group writing conferences at another American university. The findings show the emergence of social practices among the students as a result of the interrelatedness between students’ perceptions and educational environments. Although the study by Ng and Renshaw (2019) does not address L2 learning exclusively, it should be considered when investigating longitudinal changes of learner perezhivanie. They focus on one indigenous Australian student and investigate her perezhivanie in reading identities over three years. Through their detailed analysis, they found that the past-and-present connection of reading perezhivaniya (the plural form of perezhivanie) were core aspects of the development of her reading identities. According to Xu and Long (2020), such historical influences of perezhivanie on learners share the relevance for East Asian sociocultural contexts in particular because of a great deal of pressure experienced by learners. This pressure comes from both society and community (e.g., Ng, 2021; Xu & Zhang, 2023). Failing an entrance exam or other tests, for example, can cause emocognitive struggles for the learner, which will affect subsequent learning. In Japan, a person who fails an entrance exam is called a ronin, a term that symbolizes the intense competition in entrance exams in Japan (Ono, 2007). Sasaki (2008) problematizes the cases of examinees committing suicide due to “extreme anxiety” (p. 70) resulting from harsh competitiveness among applicants when they were not accepted into the university of their choice. As a practical matter, such a ronin has no social status and is as if marginalized from society, and the pressure on them to break free from this sense of isolation becomes inevitably high. To capture this entangled relationship within each agent (the unity of cognition and emotion) and between agents and their surrounding environments, it is of value to apply perezhivanie.

Advisory Sessions as Social Situation of Collectividual Development

Another closely relevant concept with perezhivanie is social situation of development (Lantolf, 2021). Veresov and Mok (2018) define this as “what could potentially develop during a particular period relative to a particular person and the force that motivate this development” (p. 91). Compared to a concrete social situation, the social situation of development will uniquely determine the various trajectories of development among individual agents. Without the lens of perezhivanie, it would be difficult to clarify why objectively similar situations would result in subjectively critical events for some people. Perezhivanie, as a unit of analysis of human consciousness (psyche), enables us to investigate the bidirectional influences between the characteristics of agency (agent’s personality) and the environment, so it reveals how a particular social situation transforms into the social situation of development through refraction, not reflection. Reflection only works as a mirror, while refraction works as a prism (Veresov & Mok, 2018).

Grounded on the principle of dialectic praxis in SCT (Lantolf & Poehner, 2014), ALL can be regarded as a mediating practice, providing learners with opportunities to shape objective social situations as subjective social situations of development. ALL encourages learners to be autonomous and agentive through collaborative dialogues with advisors (Kato & Mynard, 2016). In such advisory sessions, both advisor and advisee talk about various topics related to L2 learning to understand learners and provide a better session. In this study, it is possible to arrange our advisory sessions as situations where researchers/ advisors can elicit what learners have experienced, felt, and interpreted toward a certain circumstance thus far. These situations would then be suitable to see learner perezhivanie relevant to their L2 learning because of collaborative aspects of ALL. In other words, our dialogue with advisees deepens the prior understandings of their learning history and simultaneously mediates the co-regulatory development (collectividual development; Stetsenko, 2016). In reality, multiple studies carried out in various educational settings have indicated the contagious features of “prismatic” perezhivanie to the other interlocutor(s) through collaborative dialogue (e.g., Chen, 2015, 2022; Fleer & Hammer, 2013). Consequently, revealing different perezhivaniya across L2 learners in a Japanese sociocultural setting will enable us to understand the influences of social situation of development on agents.

Having reviewed the previous studies, this study argues that revealing learner perezhivanie in advisory settings fosters a better understanding of the influences of social situation of collectividual development (i.e., “the fundamental social nature … of individual”; Xi & Lantolf, 2020, p. 44) on both advisor and advisee. Based on this, the study explores learner perezhivanie by implementing yearlong language advisory sessions. To address this issue, two research questions were formulated:

RQ1: How did the advisee shape the environment through the emotive-cognitive dialectic in L2 learning?

RQ2: How did the advisee’s perezhivanie influence mutual advisor-advisee development?

Methodology

Participant and Context Backgrounds

As mentioned earlier, it is necessary to share the detailed background of the participant because perezhivanie considers both the agent and the environment. Wei (pseudonymous) is a Chinese learner of Japanese as an L2; she was in her mid-twenties at the time of the study. She went to a university in China and started learning Japanese in her first year of university. When she was a sophomore, she passed the JLPT N21, and when she was a junior, she studied at University A in Japan as an exchange student for a year. After that, she graduated from the university in China and directly got a job in her hometown in China, but resigned after half a year, studied at University B for a year as a non-degree student, and entered the graduate school of University B in 20xx, majoring in Asian area studies. Before being accepted to Graduate School B, Wei had been rejected by another graduate school (Graduate School C) through a document screening process and became a ronin (a Japanese term used for students who fail an entrance exam) for about six months. What makes this case interesting and revealing is that she initially failed her graduate school entrance exam, but she was successful in her subsequent attempt to pass the exam, resulting in a significant shift in her cognitive-emotional attitude and her agency as an advisee at that time.

In most Japanese entrance exams, examinees are evaluated based on their overall score (including language), but they are not informed of their official point total. Thus, they cannot determine which parts of the exam did not meet the necessary standard, even though they can know whether they pass or fail. Examinations for graduate schools in Japan are mainly divided into document screening and interviews, with emphasis on the research proposal. As stated earlier, students who wait for another chance to enter university (including graduate school) after having failed the yearly or semi-yearly entrance examination are often called ronin in Japan.

Relationships Prior to the Study

When I first met Wei, she was a non-degree student at University B. At that time, I was working once a week as a Japanese learning advisor at the university’s International Student Center. Wei voluntarily attended the center, seeking assistance with her research proposal. While there were multiple advisors available, and visitors had the freedom to choose their session time and advisor, but Wei started attending weekly sessions with me after her initial visit. During our sessions, we talked not only about the research proposal but also about her career after entering graduate school. As our dialogue deepened, I was impressed by how Wei’s perspective on graduate school evolved. Initially, she was primarily focused on gaining admission. However, she began to shift her focus towards her goals beyond admission and started considering her future prospects after completing her studies. These dialogues, which occurred before this study, may have influenced her perezhivanie as well. Since we had built a rapport over the two years prior to the study, I was able to ask her during the advisory sessions conducted as part of the study about her failure in the entrance exam; this is generally a topic which individuals are hesitant to discuss. Therefore, I believe that our relationship worked positively in investigating perezhivanie. Moreover, as an advisor/ researcher, I was able to empathize and talk with Wei because of our common backgrounds; I had also experienced being a ronin for about two years after I failed the university entrance exam, mainly because of insufficient study and financial reasons.

Data Collection and Analysis

After Wei entered Graduate School B, I continuously conducted collaboratively dialogic sessions with her in Japanese, where I recorded our sessions. The data analyzed come from two sources: (a) our written correspondence, including email exchanges, from before the study was conducted and (b) audio-recorded data of six face-to-face/ online advisory sessions (121.6 minutes on average and 730 minutes total) on a bimonthly basis with a particular focus on her perezhivanie. The sessions focused on three main topics: (a) how Wei reacted to and interpreted her failed entrance exam; (b) how she thought and acted before her second attempt as a ronin; and (c) how she retrospectively created meaning from her ronin experience after the second exam. I also asked about her individual histories that led her to certain interpretations and meanings and had resulted in her exercising her agency.

Following the analytical strategies by Ng and Renshaw (2019), I looked at the data referring to pre- and post-entrance exams from both microgenetic (moment-to-moment change; learning) and ontogenetic (longitudinal change; development) perspectives, applying perezhivanie as the unit of analysis to capture the long-term influences of ronin experiences on the participant. The former aim was to examine the original reactions toward a certain experience, and the latter one was to examine how her perezhivanie was shaped after such a dramatic event.

Findings and Discussion

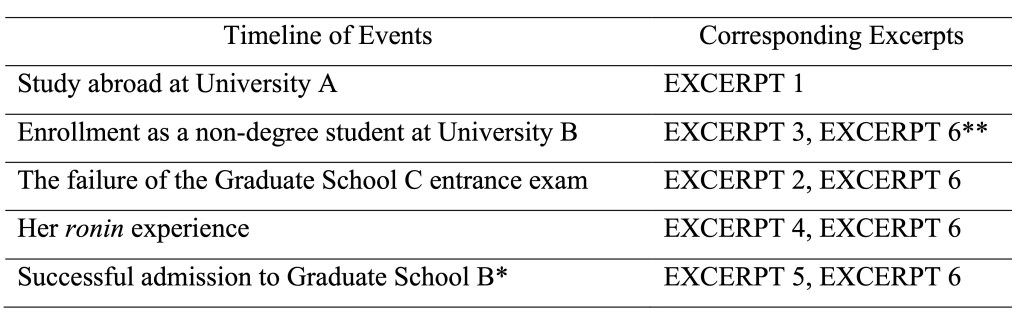

By triangulating multiple data sources, the findings revealed (a) how the participant originally reacted toward a circumstance (i.e., failure of entrance exam) and how she retrospectively interpreted this experience (i.e., perezhivanie); and (b) how she influenced and shaped the environment as a result of the emotive-cognitive dialectic (i.e., further L2 development). Notably, Wei evaluated her original experience negatively at first, but eventually, she came to appreciate the failure, resulting in a reinterpretation of the original experience. Due to the intricacy of multiple universities and timelines, Table 1 summarizes the events Wei experienced and corresponding excerpts. The following sections present data relevant to perezhivanie as excerpts (translated from Japanese) according to RQs.

Table 1

Timeline of Events Experienced by Wei and Corresponding Excerpts

Notes. University B and Graduate School B are the same school. EXCERPT 6 is listed in multiple cells because it is my reflection on about two years since we met.

Wei’s Perezhivanie: Shaping the Environment Through the Emotive-Cognitive Dialectic in L2 Learning

In the first excerpt, she reflects on her experience before a graduate school entrance exam. At the time, she felt lonely and marginalized by Japanese society, showing sociopsychological pressure.

EXCERPT 1 from the first session

Ryo: Why did you want to study abroad in Japan?

Wei: Before I entered university, I was not doing well in school and wanted to change my life by studying abroad. At that time, I was childish and had a very simple idea that my life might change if I went to another country. I also really liked Japan, so I wanted to study in Japan. But in the end, I failed. I managed to tell my parents about the idea of studying abroad, but they said no, so I chose to major in Japanese at university.

…

Ryo: How was it to actually study abroad?

Wei: I was really scared of people around me because I couldn’t speak Japanese at all. At the time, even if I had something I wanted to say in my head, I was too nervous to speak at all, which was embarrassing.

…

Ryo: What was the most impressive thing about studying abroad?

Wei: The best part of studying abroad is enduring the loneliness. I learned that the hard way. I learned it. I learned how to endure my own loneliness. … It was hard sometimes. At that time, I was crying all the time. There were people around me, people I could talk to, but I felt so lonely inside. I don’t know, I already had friends, but I still felt as if I was not a part of that society.

Although Wei’s relationship with her parents was not bad, she stated that she consistently wanted to escape from their constraints even before entering university. However, her desire to attend a university outside of China was rejected, so Wei’s junior year exchange experience at a Japanese university (University A) serves as one illustration of this. She came to study in Japan because she was fascinated by the country, but she could not fully understand the classes and could not speak Japanese well in the shared house, which made her cry from loneliness. However, this experience led her to study abroad a second time as a non-degree student and to enter a graduate school in Japan (University B), as Wei expressed, “because I really started to like Japan when I began studying Japanese.” Her decision to study abroad for the second time may have been partly due to her desire to escape the constraints of her parents. Simultaneously, she also wanted to spend another fulfilling time in Japan, as she had had many painful but enjoyable experiences during her first study abroad in Japan.

In the following excerpt, Wei reflects on the moment when she failed the entrance exam at the graduate school of University C. In this excerpt, she attributed the failure to her lack of Japanese proficiency. Even though she spent great effort in writing her research proposal, her understanding of the requirements was poor. Wei undoubtedly experienced emocognitive dissonance due to a profound and impactful event (Johnson & Worden, 2014).

EXCERPT 2 from the email exchanges at that time

Wei: Unfortunately, I failed the graduate school of University C due to my lack of ability. However, I don’t want to give up easily because of this. I am planning to try graduate school again, so I am preparing a new research proposal. However, due to my lack of ability, it is still difficult for me to complete the research proposal by myself.

Ryo: It is a pity because your research proposal improved every time I saw it. But your research is really important for the future of Japan, so please do your best even though it may be difficult now, and I support you from the bottom of my heart. If there is anything I can do to help, I will spare no effort to cooperate, so please do not hesitate to contact me.

At this point, Wei was no longer a non-degree student at University B, so there was no official requirement for me to respond. However, at the same time, I responded to her “I don’t want to give up” statement by showing my determination to support her (“I support you from the bottom of my heart”). From perezhivanie’s perspective, there are two interesting findings from this exchange. One is the bidirectional interactions of cognition and emotions Wei had from environmental influences and how she exercised agency over her environment. The other is the bidirectional interactions between her and me as her advisor, who is influenced by her perezhivanie. In other words, unlike the person-context interactions that Wei faced, in my case, the person-context interactions occurred with Wei’s perezhivanie as the environment (collective aspects of perezhivanie known as soperezhivanie; March & Fleer, 2016).

Wei cited her lack of Japanese language skills as the reason for failing the entrance exam (EXCERPT 2), and the incident that triggered this is partially evident from EXCERPT 3. She had been in contact with several professors at the graduate schools to which she was thinking of applying to, and she expressed the following:

EXCERPT 3 from the sixth session

Ryo: Are there times when you are embarrassed to use Japanese?

Wei: I emailed Professor A directly. However, I still felt that I didn’t express myself well in my own words or show proper respect to him. His reply was very intense and said that I should go back to China. I was very embarrassed at that time…his words were a bit harsh. But it was still my fault. I didn’t have my own research plan, and I didn’t have any words to explain my research interests. It’s my own fault.

Ryo: That was hard. But now that you are in graduate school like this (Graduate School B), and the result is all right.

Wei: Thanks to you, my research proposal is getting more and more concrete, and I really appreciate your help. I learned a lot. When I emailed you that day (EXERPT 2; just after the failure of the entrance exam of Graduate School C), I had no idea what to do.

In EXERPT 4, Wei reflects on her ronin experience several days after her failure (Graduate School C). While she wanted to try the entrance examination for graduate school one more time (Graduate School B), she shared that she was experiencing difficulties in writing her research proposal due to her lack of ability, including Japanese language ability. At the same time, she also mentioned the pressure to face her parents and return to China, so there were clear sociocultural pressures, as well as her lack of Japanese language proficiency. For her, not being able to go to graduate school in Japan meant that her freedom would be restricted, which she did not want.

EXCERPT 4 from the first session

Ryo: Because of your efforts and actions, your research proposal got better and you were finally accepted to Graduate School B, and that’s wonderful.

Wei: At the time (experiencing a ronin), I was having a hard time deciding on a research topic and was under a lot of stress due to pressure from my parents and returning home. I tried to save my face by meeting their expectations. I was frustrated that I didn’t get good results, but I didn’t have time to be too disappointed.

Here, even though she still felt stressed because of the pressure from her parents, she positively changed her mind for the next examination (Graduate School B) because the pressure partly facilitated her agency. Therefore, it is plausible to say that the different refraction (EXCERPT 4; after her ronin experience) by her previous perezhivaniya (EXCERPT 1 and 3; before her ronin experience) encouraged Wei to be agentive for the next entrance exam (EXCERPT 2; experiencing a ronin). This finding confirms the connection between past and present perezhivaniya, as discussed in previous studies (Ng, 2021; Ng & Renshaw, 2019). In fact, as Ono (2007) mentions, Japan’s examination hell has become a social problem, and societal as well as psychological pressure of the examinations on students is as great as in other East Asian countries and regions (e.g., China, South Korea, and Taiwan, among others). Choosing to become a ronin means that learners will be exposed to the dilemma of sociopsychological pressure and the desire to achieve their desired career path, so it is also undeniable to say that Wei was experiencing cognitive and emotional complications, but she was letting her initiative carry her towards the next entrance exam (Graduate School B). This suggests dialectical relationships of her perezhivaniya between the temporal past-present connection and the contextual person-context connection.

Collectividual Development: Advisor-Advisee Perezhivaniya Through Advising

Considering Wei’s perezhivanie in RQ1, EXCERPT 5 characterizes how I, as her advisor, was making sense of it. This excerpt was written after Wei was accepted to Graduate School B.

EXCERPT 5 from my notes at that time

Ryo: Wei came to report directly to me that she passed the entrance exam! I am happy to hear that she has been working hard to pass the graduate school entrance exam since the first time she visited me. I was deeply moved when I read back my reflection from her first visit to me. Wei’s research plan is very solid, and I wish her the best of luck in graduate school!

Although the time sequence is a few months after EXCERPT 2, I am harboring a completely different emocognitive unity from Wei. As I wrote, “I was deeply moved,” and our yearlong advisory sessions began soon after this, influenced by her agency. In light of this ‘prequel,’ the study would not have been possible without her acceptance to Graduate School B. We actually conducted sessions throughout this study, and it was appropriate to interpret Wei’s development in terms of perezhivanie, as her journey of overcoming the challenges of being a ronin and gaining admission into graduate school mirrored my ronin experience during my university entrance examinations.

EXCERPT 6 is what Wei and I discussed when we were reflecting on those days (about two years from the first session with her until she was accepted to Graduate School B). I stated the following about how I was able to develop collectividually based on my advising experiences in the different contexts of English and Japanese education:

EXCERPT 6 from the sixth session

Ryo: I originally came from an English education background, but since I was involved in the context of Japanese language education, I was able to learn across disciplines. I think the relationship is not a one-sided I-Wei relationship but a harmonious one that goes beyond one level.

As stated above in “not a one-sided I-Wei relationship but a harmonious one,” not only did the advisee learn from me (EXCERPT 3; “my research proposal is getting more and more concrete”), but I learned from the advisee (“since I was involved in the context of Japanese language education, I was able to learn across disciplines”). One illustration of this was that, inspired by Wei’s agency, I felt the need to learn more about Japanese language education, so I studied and passed the Japanese Language Teaching Competency Test (JLTCT) from scratch. Of course, advising and teaching are different practices, so passing this exam may not change anything substantially. However, I wanted to learn systematically in the JLTCT, hoping that even a little would lead to better support for advisees like Wei. As a result, it led to my personal development as a Japanese learning advisor because I learned about things specific to Japanese language education, which helped me understand the advisees’ background and give more appropriate advice. Therefore, Wei’s development story is also an impressive developmental process for me since I started studying a few months before she dropped into Graduate School C.

Coincidentally, I passed the JLTCT the same month in the same year she was accepted into Graduate School B. This bidirectional interaction is when each other’s perezhivanie between the individual and the environment is realized, and our perezhivaniya leads to collectividual development through advising (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Advisory Sessions as Social Situation of Collectividual Development

Conclusion

By applying perezhivanie as a unit of analysis that avoids the cognition-or-emotion and person-or-context dichotomies, the present study explored the developmental processes of one L2 learner and focused on how both advisor and advisee mutually transform the specific social situation into a social situation of collectividual development through yearlong advisory sessions. The findings mainly revealed (a) how Wei originally reacted toward a circumstance (i.e., EXCERPT 1 and 2; her cognitive and emotional complications caused by sociopsychological pressure and the failure of the Graduate School C entrance exam) and how she retrospectively interpreted this experience (i.e., EXCERPT 3 and 4; the different refraction by her perezhivaniya); and (b) how she shaped and influenced the environment as a result of the emotive-cognitive dialectic (i.e., EXCERPT 5 and 6; the successful admission to Graduate School B through her ronin experience and her influence on our collectividual development). Although somewhat paradoxical, these findings relevant to perezhivanie were made possible by focusing not only on data about individuals (Wei in this study) but also on the advisor-advisee relationship, which makes up the advising session.

In conclusion, as discussed above, each perezhivanie has refracted the experiences of being ronin in the different make-meanings and interpretations so that understanding learner perezhivaniya leads to more in-depth dialogic sessions for both advisor and advisee and to collectividual development within those sessions. These differences in responses represent different influences of the social situation on the participant, according to dialectical relationships of perezhivaniya between the temporal past-and-present connection and the contextual person-and-context connection. Through the prism of perezhivanie, this study revealed the transformative processes from social situation to the social situation of collectividual development in the case of a JSL advisee and Japanese language advisor (Figure 1).

The significance of the study is to contribute to describing the detailed case of learner perezhivanie with a particular focus on entrance exams in East Asian sociocultural settings. In this regard, by applying perezhivanie as a unit of analysis in studying learner development, this study makes a unique contribution to understanding the dialectical relations of the individuals and the sociocultural environment as an indivisible unity in an East Asian setting and how East Asian learners, who often experience a great deal of pressure of examinations (Xu & Long, 2020), transform the social situation into the social situation of development. Therefore, the understanding of our sessions would indicate the longitudinal change of perezhivanie through advising and how such developmental processes are supported by mediation in a Japanese cultural context as well as in an advisory setting. Further study may explore the developmental processes of learners with different L2s and how their different perezhivaniya will emerge toward similar experiences in a Japanese cultural context. It may also allow exploration about how different perezhivaniya themselves refract other’s perezhivanie and mediate the co-regulatory development for each other in advisory sessions.

Notes on the Contributor

Ryo Moriya is a Ph.D. candidate and a research associate at the Faculty of Education and Integrated Arts and Sciences, Waseda University, Japan. He holds an MA in Education from Waseda University, where he has served as a Japanese and English learning advisor. His research interests include advising in language learning, sociocultural theory, and perezhivanie.

Notes

1: JLPT (n.d.) is the acronym of Japanese-Language Proficiency Test co-conducted by Japan Foundation (JF) and Japan Educational Exchanges and Services (JEES). This test has five levels, from N5 (beginner-level) to N1 (advanced-level).

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend my sincere thanks to Wei for the irreplaceable opportunity for collectividual development throughout the year. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP21K20222.

References

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching: Autonomy in language learning (2nd ed.). Pearson Education.

Chen, F. (2015). Parents’ perezhivanie supports children’s development of emotion regulation: A holistic view. Early Child Development and Care, 185(6), 851–867. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2014.961445

Chen, F. (2022). Co-development of emotion regulation: Shifting from self-focused to child-focused perezhivanie in everyday parent-toddler dramatic collisions. Early Child Development and Care, 32(3), 370–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1762586

Donato, R., & Davin, K. J. (2018). The genesis of classroom discursive practice as history-in-person processes. Language Teaching Research, 22(6), 739–760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817702672

Fleer, M., González Ray, F. L., & Veresov, N. (Eds.). (2017). Perezhivanie, emotions and subjectivity: Advancing Vygotsky’s legacy. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4534-9

Fleer, M., & Hammer, M. (2013). ‘Perezhivanie’ in group settings: A cultural-historical reading of emotion regulation. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 38(3), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911303800316

Johnson, K. E., & Golombek, P. R. (2016). Mindful L2 teacher education: A sociocultural perspective on cultivating teachers’ professional development. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315641447

Johnson, K. E., & Worden, D. (2014). Cognitive/emotional dissonance as growth points in learning to teach. Language and Sociocultural Theory, 1(2), 125–150. https://doi.org/10.1558/lst.v1i2.125

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

Kjisik, F., Voller, P., Aoki, N., & Nakata, Y. (Eds.). (2009). Mapping the terrain of learner autonomy: Learning environments, learning communities and identities. Tampere University Press.

Lantolf, J. P. (2017). Materialist dialectics in Vygotsky’s methodological framework: Implications for applied linguistics research. In C. Ratner & D. N. H. Silva (Eds.), Vygotsky and Marx: Toward a Marxist psychology (pp. 173–189). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315276632-8

Lantolf, J. P. (2021). Motivational dialogue in the second language setting. International Journal of TESOL Studies, 3(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.46451/ijts.2021.09.01

Lantolf, J. P., & Poehner, M. E. (2014). Sociocultural theory and the pedagogical imperative in L2 education: Vygotskian praxis and the research/practice divide. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203813850

Lantolf, J. P., & Poehner, M. E. (2023). Sociocultural theory and classroom second language learning in the East Asian context: Introduction to the special issue. The Modern Language Journal, 107, 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12816

Lantolf, J. P., Poehner, M., & Swain, M. (Eds.). (2018). The Routledge handbook of sociocultural theory and second language development. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315624747

Lantolf, J. P., & Swain, M. (2020). Perezhivanie: The cognitive-emotional dialectic within the social situation of development. In A. H. Al-Hoorie & P. D. MacIntyre (Eds.), Contemporary language motivation theory: 60 years since Gardner and Lambert (1959) (pp. 80–105). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788925211-009

Lantolf, J. P., Thorne, S. L., & Poehner, M. (2020). Sociocultural theory and L2 development. In B. VanPatten, G. D. Keating, & S. Wulff (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction (pp. 223–247). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429503986-10

Little, D., Dam, L., & Legenhausen, L. (2017). Language learner autonomy: Theory, practice and research. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783098606

March, S., & Fleer, M. (2016). Soperezhivanie: Dramatic events in fairy tales and play. International Research in Early Childhood Education, 7(1), 68–84. https://doi.org/10.4225/03/580ff9b268be2

Mochizuki, N. (2019). The lived experience of thesis writers in group writing conferences: The quest for “perfect” and “critical”. Journal of Second Language Writing, 43, 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2018.02.001

Mok, N. (2015). Toward an understanding of perezhivanie for sociocultural SLA research. Language and Sociocultural Theory, 2(2), 139–159. https://doi.org/10.1558/lst.v2i2.26248

Mok, N. (2017). On the concept of perezhivanie: A quest for a critical review. In M. Fleer, F. González Rey, & N. Veresov (Eds.), Perezhivanie, emotions and subjectivity: Advancing Vygotsky’s legacy (pp. 19–45). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4534-9_2

Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2012). The skills of counselling in advising: Language as a pedagogical tool. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 43–64). Pearson.

Murray, G., & Lamb, T. (Eds.). (2018). Space, place and autonomy in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781317220909

Mynard, J. (2019). Self-access learning and advising: Promoting language learner autonomy beyond the classroom. In H. Reinders, S. Ryan, & S. Nakamura (Eds.), Innovation in language teaching and learning: The case of Japan (pp. 185–209). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12567-7_10

Mynard, J. (2020). Advising for language learner autonomy: Theory, practice, and future directions. In M. J. Raya & F. Vieira (Eds.), Autonomy in language education: Theory, research and practice (pp. 46–62). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429261336-5

Mynard, J., & Kato, S. (2022). Enhancing language learning beyond the classroom through advising. In H. Reinders, C. Lai, & P. Sundqvist (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language learning and teaching beyond the classroom (pp. 244–257). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003048169-20

Ng, C. (2021). Japanese students’ emotional lived experiences in English language learning, learner identities, and their transformation. The Modern Language Journal, 105(4), 810–828. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12739

Ng, C., & Renshaw, P. (2019). An indigenous Australian student’s perezhivanie in reading and the evolvement of reader identities over three years. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 22, 100310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.04.006

Ono, H. (2007). Does examination hell pay off? A cost–benefit analysis of “ronin” and college education in Japan. Economics of Education Review, 26(3), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2006.01.002

Poehner, M. E. (2016). Sociocultural theory and the dialectical-materialist approach to L2 development: Introduction to the special issue. Language and Sociocultural Theory, 3(2), 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1558/lst.v3i2.32869

Poehner, M. E., & Swain, M. (2016). L2 development as cognitive-emotive process. Language and Sociocultural Theory, 3(2), 219–241. https://doi.org/10.1558/lst.v3i2.32922

Sasaki, M. (2008). The 150-year history of English language assessment in Japanese education. Language Testing, 25(1), 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532207083745

Shelton-Strong, S. J., & Tassinari, M. G. (2022). Facilitating an autonomy-supportive learning climate: Advising in language learning and basic psychological needs. In J. Mynard & S. J. Shelton-Strong (Eds.), Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom: A self-determination theory perspective (pp. 185–205). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788929059-013

Stetsenko, A. (2016). Moving beyond the relational worldview: Exploring the next steps premised on agency and a commitment to social change. Human Development, 59(5), 283–289. https://doi.org/10.1159/000452720

Stone, L. D., & Hart, T. (2019). Sociocultural psychology and regulatory processes in learning activity: Contributions of cultural-historical psychological theory. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316225226

Swain, M., Kinnear, P., & Steinman, L. (2015). Sociocultural theory in second language education: An introduction through narratives. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783093182

The Japan Foundation, & Japan Educational Exchanges and Services (n.d.). What is the Japanese-Language Proficiency Test? https://www.jlpt.jp/e/about/index.html

Veresov, N., & Mok, N. (2018). Understanding development through the perezhivanie of learning. In J. P. Lantolf, M. Poehner, & M. Swain (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of sociocultural theory and second language development (pp. 89–101). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315624747-6

Vygotsky, L. S. (1994). The problem of the environment. In R. van der Veer & J. Valsiner (Eds.), The Vygotsky reader (pp. 338–354). Blackwell.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1997a). The historical meaning of the crisis of psychology. In R. W. Rieber & J. Wollock (Eds.), Collected works of L. S. Vygotsky: Vol. 3. Problems of the theory and history of psychology (pp. 233–344). Plenum Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1997b). The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky, Vol. 4: The history of the development of higher mental functions. Plenum Press.

Xi, J., & Lantolf, J. P. (2020). Scaffolding and the zone of proximal development: A problematic relationship. Journal for the Theory and Social Behaviour, 51(1), 25–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12260

Xu, J., & Long, Z. (2020). Sociocultural theory and L2 learning: A review of studies in East Asia. Language and Sociocultural Theory, 7(2), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1558/lst.19401

Xu, J., & Zhang, S. (2023). The effect of the cognitive–emotional dialectic on L2 development: Enhancing our understanding of perezhivanie. The Modern Language Journal, 107, 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12823