Katherine Thornton, Otemon Gakuin University, Japan

Thornton, K. (2023). Linguistic diversity in self-access learning spaces in Japan: A growing role for languages other than English? Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(2), 201–231. https://doi.org/10.37237/140206

Abstract

In line with foreign language instruction in general, foreign language provision in self-access learning centres (SALCs) has been dominated by English language learning. This is largely due to the nature of the internationalisation agenda in Japan, termed kokusaika, which emphasises English as the most important international language, the learning of which can facilitate Japanese economic advancement (Hashimoto, 2017; Kubota & Takeda, 2021). Largely missing from this narrative is a promotion of multiculturalism within Japan between different migrant populations, for many of whom English is as much a foreign language as it is for Japanese nationals (Tsuneyoshi, 2018). In order to truly internationalise, Japan must understand and embrace the linguistic and cultural diversity within its borders. Therefore, international education should focus on more than simply English education. This is as true for self-access facilities as it is for the mainstream curriculum. While there is some provision in some facilities for languages other than English (LOTE), as yet, no systematic investigation into the degree and nature of this provision has been conducted. Using data from a survey administered with coordinators of SALCs across Japan, this study investigated the degree to which SALCs in Japan are focusing on LOTE and the different ways in which they support these languages. The results revealed increasing focus on LOTE in some SALCs, in terms of materials and services offered, and significant linguistic diversity among SALC staff. However, common heritage and indigenous languages in Japan are largely absent, and a tendency to see language provision primarily as the appropriate balance between English and Japanese still persists in some SALCs.

Keywords: self-access management, multilingualism, linguistic diversity, languages other than English, language policy

The overwhelming dominance of English in foreign language education in Japan has led to the downplaying, or even erasure, of the linguistic diversity evidently present in Japanese society (Kubota, 2002). Without an understanding of this multilingual and multicultural diversity and a nuanced understanding of how to successfully communicate with people from different backgrounds, young Japanese may struggle to engage in meaningful relationships with these residents and citizens, let alone be able to take a place on the world stage (Tsuneyoshi, 2018). In this paper, I argue that self-access learning centres (SALCs) can provide leadership in this area and help students become more rounded global citizens, beyond just the development of English language skills. I first examine the discourses relating to linguistic diversity present in Japanese society, then attempt to ascertain their influence on language provision in Japanese SALCs. My analysis of a survey administered with SALC directors and coordinators across Japan reveals the degree to which SALCs are currently supporting the learning of languages other than English (LOTE). I hope these findings can start a discussion about what more can be done to create more space for other languages alongside English and give more learners in Japan the opportunity to understand the importance of linguistic diversity and to develop intercultural communication skills.

Linguistic Diversity in Japan

While proponents of nationalistic theories of Japanese identity such as nihonjinron(日本人論), “the question of the Japanese people”, insist that Japan is racially, culturally and linguistically homogenous (Miller, 1982), there is now general recognition that Japan is indeed far more diverse than these theories allow for (Kubota, 2002; Lie, 2001; Maher & Yashiro, 1995), and a number of languages other than Japanese are in common use across the country. That said, determining the actual degree to which languages other than Japanese are used across Japan society is a complicated endeavour. Official statistics from the 2020 census in Japan show a relatively low foreign resident population of 2.4 million people, which accounts for a little less than 2% of the total population (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, 2022). Of this number, the most numerous populations have their origins in China, North and South Korea, Vietnam, the Philippines and Brazil. However, taken as a measure of linguistic or cultural diversity, this number is misleading for several reasons. Firstly, it does not include Japanese nationals who can be regarded as multicultural and multilingual, such as naturalised citizens born overseas, or children of Japanese nationality with a non-Japanese parent. It also overlooks the growing number of Japanese with significant ties to other cultures and languages who may have spent a large portion of their lives overseas, or may be in relationships with non-Japanese. Neither do these data include the speakers of indigenous languages in Japan, such as Ainu and Okinawan languages, as these citizens have Japanese nationality. Admittedly the total number of speakers of these languages is very low, but it is still an important demographic from a historical and multicultural perspective. Additionally, a small number of foreign residents, especially those with Korean nationalities (so-called zainichi) come from families who have lived at least three generations in Japan and may lack strong links to their linguistic heritage, so these data may actually overrepresent the current number of Korean speakers.

Another way to get a sense of the number of different languages being used in Japanese society is to examine which languages are used to support newly-arrived residents of the country. As of its last update in 2019, the Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR), offered guides for living in Japan in 13 languages in addition to Japanese (CLAIR, 2019), whereas the Ministry of Justice’s Immigration Services Agency also offers an online daily life support portal in 13 languages, with some support also given in 12 more, most recently Ukrainian (Ministry of Justice, 2022). While these sources can provide a sense of the different populations and the languages they are using, they do not, however, give any information about the relative size of these populations and are highly likely to underrepresent the number of languages actually spoken by the populations at which they are aimed, who are often highly multilingual. Nevertheless, this is further evidence of the degree of multilingualism which exists in Japan.

The Dominance of English in Language Education in Japan

Given this presence of multiple languages in Japan, to what extent are they reflected in language-in-education policies? Takahashi (2022) tracks an ever-decreasing trajectory of LOTE education at the tertiary level, from the pre-war era, when languages such as French and German were taught to a high level (albeit to a tiny elite group of students), to the post-war era, when English became more dominant, on to the liberalisation of the university system in the 1990s, which has resulted in fewer foreign language requirements being specified by the Ministry of Education. A survey of 360 colleges revealed that more than 50% of institutions had no compulsory LOTE classes (JACET, 2002, cited in Takahashi, 2022). Citing government policies and initiatives promoting English as an international language in the run up to the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, Sugita McEown et al. assert that “the Japanese government has voiced an unmistakable political interest in promoting English education over other foreign language education” (2017, p. 537).

This subsequent dominance of English in the Japanese education system is closely associated with a distinctive Japanese model of internationalisation, termed kokusaika (国際化),which has been linked to nationalist models of Japanese identity such as nihonjinron (日本人論)(Hashimoto, 2000, 2017; Kubota, 2002; Liddicoat, 2007). In this neoliberal model, English is seen as the “unquestioned international language” (Liddicoat, 2007, p. 36), to be acquired by an ethnically and linguistically monocultural Japanese population to communicate with a predominantly Western and English-speaking outside world, in order to promote Japanese culture and enhance the economic prosperity of Japan (Hashimoto, 2017; Kubota & Takeda, 2021). Ushioda (2017) points out that such instrumental views on language learning as a tool for advancement, as seen in Japan, can work against the promotion of LOTE, as these languages are often perceived to have lesser immediate economic value than English.

Tsuneyoshi (2018) highlights that “foreign language” is used almost synonymously with “English” in the discourse around internationalisation and foreign language education in Japan, and a 2016 survey by the Ministry of Education showed that over 90% of the foreign language activities at upper-elementary school level were focussed on English (MEXT, 2016 as cited by Tsuneyoshi, 2018, p. 50). In Tsuneyoshi’s view, this narrow definition of international education simply being a matter of “learning English” is harmful as it assumes an English-speaking, often Caucasian short-term visitor to Japan to be the only kind of “foreigner” that children should learn to interact with, therefore excluding longstanding colonised ethnic minorities such as Koreans and Chinese, and more recent migrant populations speaking Portuguese, Tagalog and other languages. She argues that the inclusion of these populations is vital for a truly multicultural form of internationalisation, in which young Japanese can learn about Japan’s complicated relationship with other countries and understand the different waves of migration and their causes. However, the emphasis on English means this perspective is mostly lacking in current internationalisation policy. Murakawa (2018) and Pearce (2021) make similar observations about the role of English and the lack of representation of non-English speaking foreign populations in teaching materials for foreign language education in Japan, which has resulted in a de facto multilingual policy which promotes only English and Japanese, which Murakawa (2018) terms “double monolingualism”, rather than a true multilingualism which aims to be inclusive of wider ethnic groups and languages present in Japan.

LOTE in Self-Access in Japan

To what extent is this general dominance of English in language education in Japan, as detailed above, reflected in self-access provision? A brief examination of articles published about the Japanese context in JASAL Journal and Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal confirms that a vast majority of self-access language learning literature in Japan focuses on the learning of English, and to a lesser extent, Japanese as a foreign language (JFL). Encouragingly, there is a growing body of work examining language policy in Japanese SALCs, which documents a shift away from English-only policies to ones which promote translanguaging (Adamson & Fujimoto-Adamson, 2012; Imamura, 2018; Thornton, 2018) or a more multilingual focus (Murray & Fujishima, 2016; Wongsarnpigoon & Imamura, 2020, 2021). Looking specifically at student perceptions, Thornton’s (2020) investigation into student attitudes to SALC language policy revealed that students in both institutions surveyed were supportive of multiple language use in their SALCs. However, relatively few studies have documented specific provision of LOTE. One such study is from Hayashi et al. (2022), who describe the inclusion, since 2016, of student-led language table events for several languages including Chinese, Korean, Spanish, French, Russian and Malaysian, which are run by student teaching assistants with those linguistic backgrounds. Wongsarnpigoon and Watkins (2022) reported on a multilingual festival recently held at their SALC over three days where students and staff taught mini-lessons for over 10 languages, including lesser taught languages such as Tagalog, Malagasy and Polish. They highlighted how the event provided speakers of different heritage languages an opportunity to share and celebrate their languages.

Despite the welcome emergence of these kind of studies on such initiatives, what is still lacking is broader research which documents the current situation of LOTE in SALCs in Japan.

An Exploratory Study into LOTE Provision in Japanese SALCs

The lack of studies specifically addressing multilingual provision in self-access environments inspired the present study. The aim of the research was to establish an overview of the current availability of resources and support for LOTE in SALCs in Japan and attitudes to linguistic diversity among SALC practitioners. It was guided by the following research questions:

- Which languages are supported in SALCs in Japan, and how?

- To what extent are SALC coordinators and institutions supportive of approaches which promote linguistic diversity?

Data Collection and Analysis

An online survey (see Appendix*) was designed to ascertain what services were available in SALCs across Japan and in which languages they were offered, with a number of open-ended questions which probed attitudes of coordinators to the provision of LOTE and the promotion of linguistic diversity in Japan. Information such as the size of each institution and the number of languages offered as degrees or credit-bearing courses was also collected. The wording of several questions was amended based on feedback from a pilot with two participants, and then the survey was sent to directors and coordinators of self-access spaces listed on the Japan Association for Self-Access Learning (JASAL)’s registry of language learning spaces (JASAL, n.d.). A request for participation was also posted on JASAL’s online discussion group. In total 35 responses were received, but eight responses provided little or only minimal information, so only 27 were included in the final data set. This represents approximately half of the SALCs on the registry.

The survey findings provided both quantitative and qualitative data. The quantitative data focussed on LOTE provision and the wider context of each institution. The qualitative data revealed more details about certain aspects of the provision, and the attitudes of stakeholders to the promotion of linguistic diversity. Open-ended questions were subjected to a thematic analysis to determine common themes in the responses, and then further analysed in light of the demographic data to discover any discernible patterns.

Findings

Language Provision and Services

Language Provision

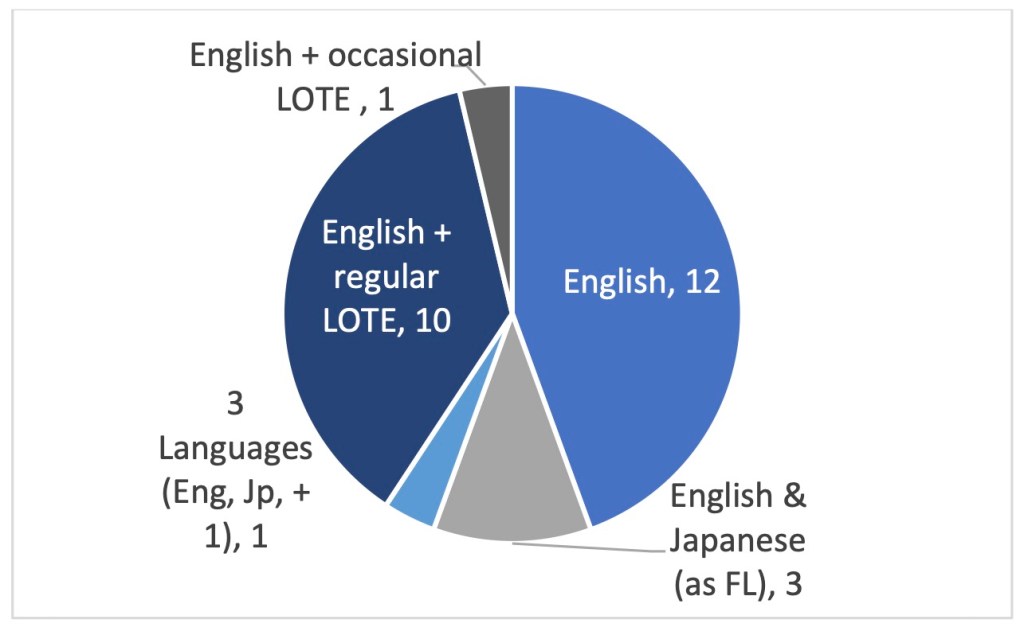

Respondents were asked to state which languages are supported in their facility, then to list the languages offered in each kind of service offered (see further details of this breakdown in Figure 6). From this data, five categories of language provision at SALCs were identified (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Language Provision at Japanese SALCs (n=27)

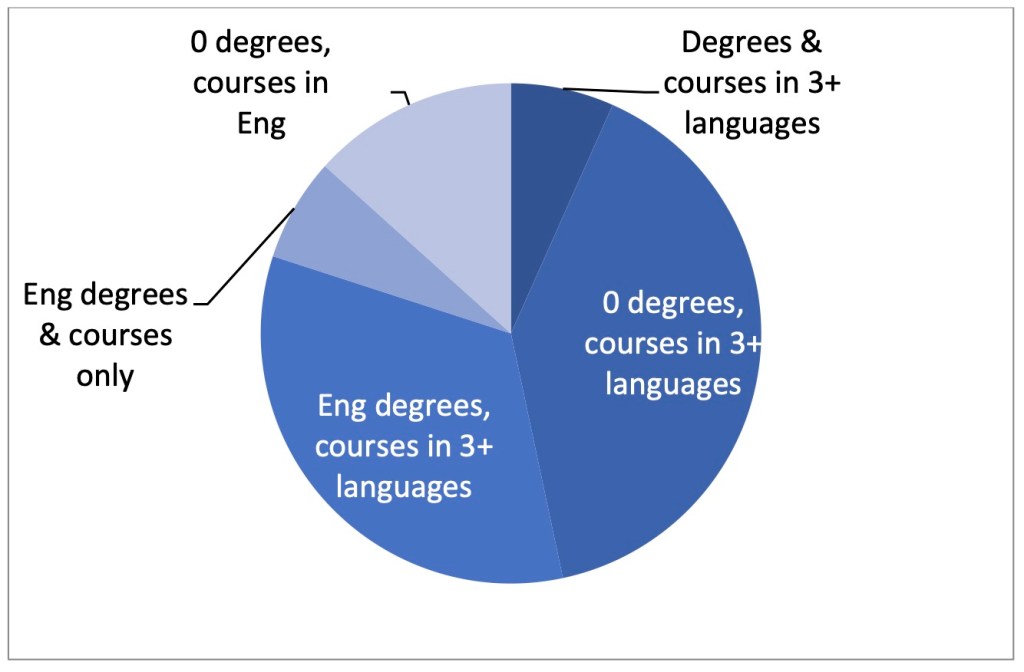

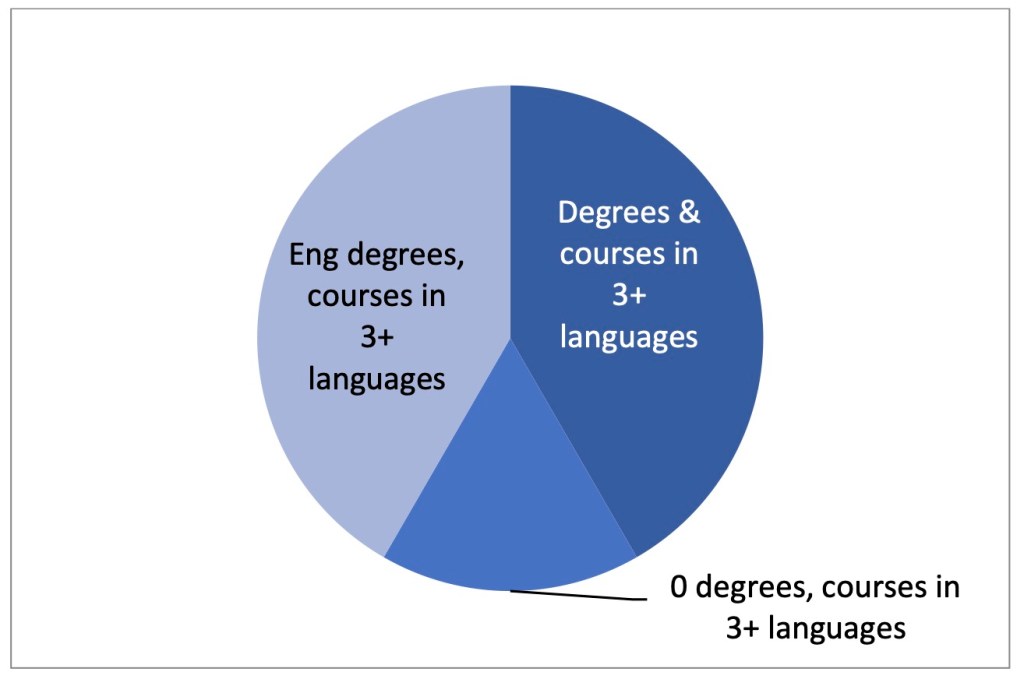

Understanding the overall emphasis placed on foreign languages by the wider institutions may provide some context to this data. Figures 2 and 3 show foreign language provision, in terms of bachelor’s degrees and credit-bearing courses, at each institution surveyed, divided into two categories which are a simplification of the data in Figure 1: English-focussed SALCs (n=15), and SALCs with LOTE provision (n=12). The data shows that institutions which support LOTE in the curriculum (degrees and credit-bearing courses) are more likely to have SALCs which also offer a degree of LOTE provision, although students at institutions whose SALCs focus is English often also have the opportunity to take classes, or in one case, a bachelor’s degree, in LOTE, but have no support for these languages in the SALC.

Figure 2

Foreign Language Provision at Institutions With English-Focussed SALCs (n=15)

Figure 3

Foreign Language Provision at Institutions Where SALCs Have LOTE Provision (n=12)

Language Policy

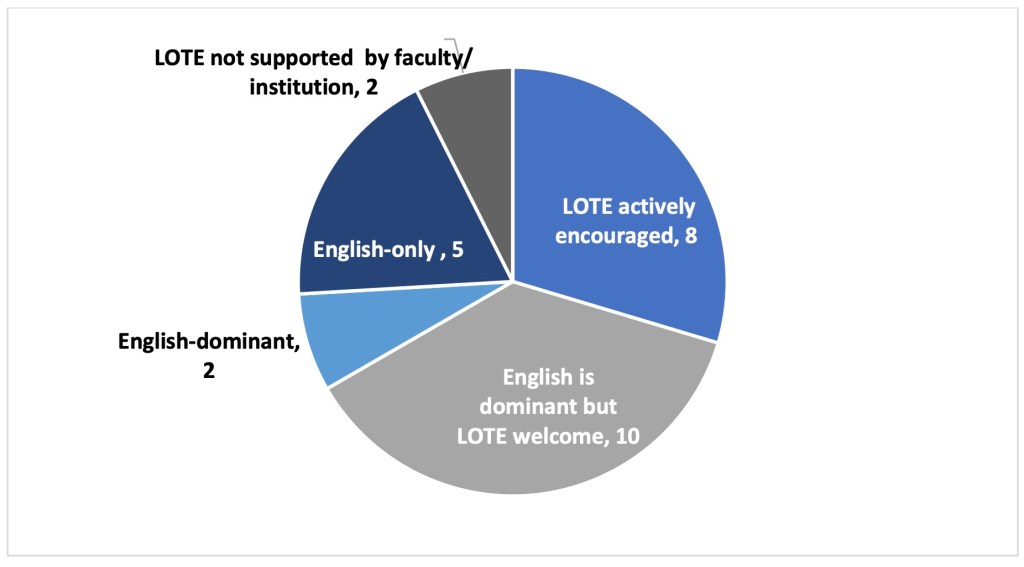

In an open-ended question, respondents were also asked to state the language policy of their facility, if any. While some policies were quite simply expressed, others were more complicated, with different policies in different spaces, at different times or for different services. Figure 4 is an attempt to categorise the policies described. As the chart shows, the most common emphasis was on English and on providing an environment for learners to communicate in this language, although only five institutions had exclusive English spaces. This echoes previous research on this issue (Thornton, 2017, 2018), which identified a broadly similar breakdown.

Figure 4

Language Policy in Japanese SALCs (n=27)

A closer look at the open-ended responses to the language policy question from which these categories were determined helped to provide some context to the stated policy in each SALC. Five respondents referred to the need to provide a welcoming environment by not strictly prescribing the language of communication, and in general the responses revealed a preoccupation with the degree of Japanese “allowed” in an otherwise English space, rather than the provision of languages in general, as shown in the following excerpts from the data.

Prompt: Does your SALC have a language policy? If so, what is it?

We do not forbid the use of some Japanese during English conversation, if that is what the question is about. Using English (or another foreign language) as much as possible is encouraged, but not strictly enforced.

English through English. However, for the writing support desk we accommodate interaction in Japanese to help scaffold the goals with less confusion.

There is no officially stated language policy. However, we strongly encourage students to communicate in English in our SALC, especially when speaking to instructors. When necessary, Japanese is used to facilitate, communicate, and attend to student needs.

We shifted from the “English only” policy to “English please” several years ago to encourage use of the targeted language in the SALC while not intimidating students. Because many students feel scared to step into the SALC due to the language policy, we explain that they can use Japanese when they struggle with English. Still, to improve their English skills and maintain the English-using environment, we want students to follow the policy as much as possible and use English.

“English Please” policy. We encourage students to use English for all interactions within the space, but allow for some level of code-switching and use of L1 if they do not know the English word/phrase.

Of the multilingual policies, only one was in an English-focussed facility and was expressed in the following way:

In the SALC designated areas, a (any) foreign language is requested. However, this is not enforced unless during specific SALC functions or events.

Perhaps predictably, no English-only policies were in place in facilities with LOTE provision, but one did have an “English First” policy for most of the SALC:

Our default policy is English First. That means, in most areas and at most times, we encourage students to use English. We try to do this in a positive way. In our non-English programs, however, as many students are at a low level, a combination of languages are regularly used, including the target language, English and/or Japanese. It should also be noted that we have a very diverse team who lead our program sessions, consisting of undergraduates, graduates, and teachers, and these individuals come from many different countries (including Japan) and have varying proficiencies in English, Japanese and other languages.

Materials Provision

In order to get a sense of which languages are actively being supported by SALCs in Japan, respondents were asked to give details of the different services offered and the languages these services cater for. Nine SALCs (33%) provided materials in languages other than English or JFL. The variety of languages can be seen in Figure 5, which gives the languages featured in materials at two or more institutions.

Figure 5

Languages of Study Materials Offered at Two or More Institutions (n=27)

In addition to the languages shown in Figure 5, the following languages also appeared once each in the data on materials: Burmese, Danish, Hungarian, Mongolian, Persian, Portuguese, Russian, Swahili, Swedish, Turkish, and Urdu, plus the indigenous languages of Ainu and Okinawan.

Services Offered for LOTE

In addition to providing materials, 15 institutions offered various services for languages other than English and Japanese (see Figure 6). While many institutions offer services for learning JFL, this data has been omitted from the results as it is mostly directed at a different population, i.e., short- or long-term international students who are studying Japanese.

Figure 6

LOTE Services Offered in Japanese SALCs

The most common service offered were conversation sessions, offered by eight institutions, and in eight different languages in total. Across all these services, the most common languages offered were Chinese (distinctions were rarely made between different Chinese languages such as Mandarin and Cantonese), Korean, French and Spanish. Other languages which appeared are other Asian languages such as Thai, Malaysian and Vietnamese, and European languages such as Italian, Portuguese and German. Tandem programmes offered the most diverse range of languages, including Finnish and Arabic, while languages such as Welsh and Swahili also appeared for one-off events or workshops.

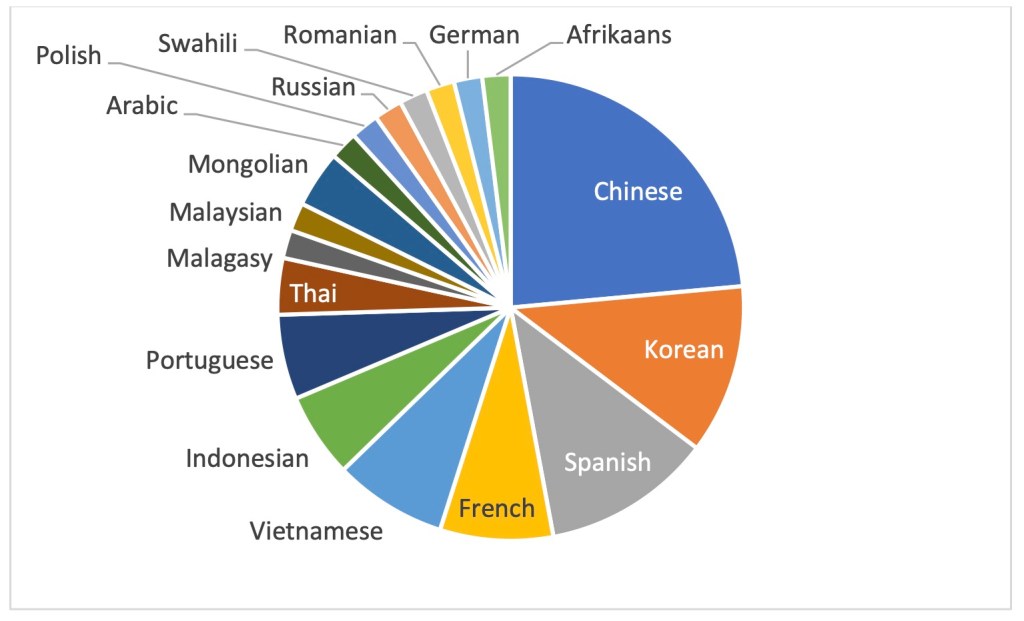

Linguistic Expertise of SALC Staff

Another way to measure to what extent SALCs can provide support for multiple languages is to examine the linguistic diversity present among SALC staff. Respondents were asked to report which languages were spoken to intermediate level or higher by members of staff (academic and administrative) and student staff. The results are shown in Figures 7 and 8. Over half of the SALCs had three or more languages spoken among the staff, with three centres having nine or more languages represented. There was a huge diversity in the languages spoken, with 18 languages mentioned in total (excluding English and Japanese).

Figure 7

Number of Languages Spoken by SALC Staff and Student Staff (n=27 institutions)

Figure 8

Languages Spoken by SALC Staff and Student Staff, Excluding English and Japanese (n=27 institutions)

Unsurprisingly, SALCs with LOTE provision were much more likely to employ staff speaking a range of languages, although several English-only SALCs did have staff who speak other languages, and in one case up to eight languages were spoken by staff of an English-focussed SALC. While larger centres were understandably more likely to have more linguistic diversity represented in their staff teams, even small centres with fewer people working there often had staff proficient in three or four languages. No distinction was given between full-time staff and student staff, so some of this diversity could probably be attributed to international students working in the SALCs.

Stance Towards LOTE at SALCs

The second part of this study attempted to establish to what extent coordinators and the wider stakeholders at SALCs in Japan are supportive of movements to promote linguistic diversity, given the dominance of English as the primary focus of foreign language education across the country. In open-ended questions, participants were asked to describe their SALC’s current stance on languages other than English, their personal attitude towards this stance and whether there have been any changes in this stance over time.

Current Stance

By analysing the responses to the open-ended responses about each SALC’s current stance, five categories were identified (see Figure 9), ranging from a stance in which LOTE are actively encouraged, to a strong English-only stance. Two respondents stated that LOTE are not supported by their institutions.

Figure 9

Stance Towards LOTE in Different SALCs (n=27)

Interestingly, these results do not correlate neatly with the results of the earlier question inquiring into overall language provision (see Figure 1). Three of the respondents who stated that their SALC actively promotes multilingualism run English-only SALCs, and a further four of these SALCs have stances which welcome LOTE despite having a dominant English focus. Of the 11 SALCs which support more than two languages, five were identified here as nevertheless having a dominant English focus while welcoming LOTE, with the others actively encouraging LOTE. This means that of these 11 facilities with regular or occasional provision for LOTE, only six could be truly described as having a multilingual focus (i.e., not described as English-dominant).

To illustrate these points, Table 1 shows several comments from the data set, illustrating different stances given, with information about the actual provision of LOTE added for reference.

Table 1

Examples of Difference Stances to LOTE

Changes in SALC Stance

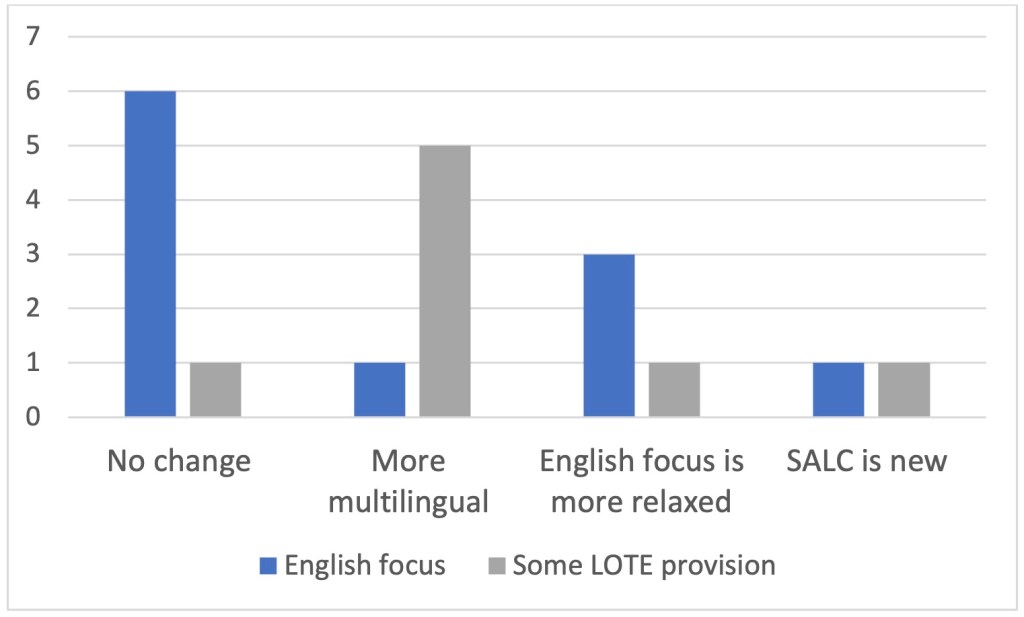

Figure 10 shows the trends that were revealed in respondent data on whether the stance to LOTE has changed over time at each SALC. While half the English-focussed centres have not seen a change in their stance, the general trend is towards either the English-focus becoming more relaxed (insistence on English-only communication being less strict or learners’ L1s explicitly being encouraged) or more languages being introduced or encouraged.

Figure 10

Changes Over Time in SALC Stance on LOTE

Support for and Barriers to LOTE Promotion and Provision

The final section of the survey was designed to elicit responses about what kind of institutional support was in place for the current language stance of each SALC and also what barriers were being experienced. Table X gives a summary of the focus of these comments.

Table 2

Support for and Barriers to LOTE Promotion and Provision

The sources of support raised by respondents focussed primarily on supportive attitudes of colleagues, institutional backing, and to a lesser extent, budget. In contrast, many responses to the question on barriers to the language stance of SALCs focussed on hurdles to general SALL provision, rather than the current language stance of the SALC in particular. Table 2 includes only comments which focussed on barriers to offering LOTE. Of these barriers, the low level of student interest would seem to be particularly challenging, given that SALCs are social learning spaces that rely on building a community of practice to sustain student motivation for learning (Murray & Fujishima, 2016; Mynard et al., 2020). As a result of the dominant English narrative, however, there may well be students who would enthusiastically embrace other languages but have not seriously considered learning them.

Discussion

The findings of the survey show that LOTE are being supported in some SALCs across Japan in a number of different ways. In this section, I highlight some themes in the data and discuss what may be influencing the choices SALC coordinators are making about which languages to support and how to do so.

Influence on SALCs of LOTE Provision in the Curriculum

There is clear correlation between the presence of LOTE in SALCs and their provision in the wider institution (Figures 2 & 3). Institutions whose SALCs have some LOTE provision are more likely to be more multilingual in the degrees they offer, with five of these 12 institutions awarding degrees in at least three languages, and with the largest, a major national university, offering 25 languages at degree level. In contrast, all but one of the 15 institutions in the data set with English-focussed SALCs either do not award degrees in foreign languages at all, or do so only in English. It is understandable, as SALCs often have very limited resources, especially in terms of staffing, that supporting LOTE is less of a priority if no students at the institution are studying them for their degree. However, this is not true across the board. One of the English-focussed SALCs is actually in a foreign languages university offering eight different languages as majors. While no SALC support is offered for these languages, it is not clear whether there is any other extracurricular provision to support LOTE students.

Even if LOTE are not being studied to degree level, only three of the 27 institutions do not offer any credit-bearing courses in languages other than English or Japanese. This shows that there are students taking courses in at least one LOTE at almost every institution featured in the data set, but in 12 of these 24 institutions, there is no support for this in their SALC. This suggests a need that these SALCs are not yet meeting.

Relative Popularity of Different LOTE

Figures 5 and 6 highlight the degree to which different LOTEs feature in SALCs in Japan, in terms of materials and services such as workshops and conversation sessions. In this section I discuss the possible reasons for the discrepancies in the provision of support for different languages.

Commonly Supported Languages

Chinese and Korean have the biggest presence in this data set. The popularity of these East Asian languages likely comes from the proximity of China (and other countries with Chinese-speaking populations such as Singapore and Malaysia) and the Korean peninsula to Japan. Due to their colonial history, the next most popular languages, French and Spanish, are certainly languages with a global reach, and their inclusion may also be influenced by the educational experiences of non-Japanese anglophone SALC staff, as they may be commonly taught in their countries of origin.

Rarely Supported Languages

Potentially more interesting than examining which languages are supported through these services is to look at which languages are largely absent from the data set. There is little mention of major world languages spoken by hundreds of millions of people in Central and South Asia and the Middle East, such as Russian, Hindi, Urdu or Arabic. When these languages do appear, they are more likely to feature as part of events or workshops with a broad cultural focus, rather than a linguistic one which places emphasis on actively learning the language. Despite Japan having a sizable Brazilian population, Portuguese is also only featured three times, once for materials, once for tandem learning and once for conversation sessions. Another language used by a sizable recent immigrant community, Vietnamese, had a similar presence in the data set. Due to long-standing colonialist narratives and the presence of a Western bias, French and Spanish may be considered to have more prestige, whereas in contrast, languages such as Portuguese and Vietnamese may be more associated with migrant labour populations, and hence have less prestige in the eyes of both staff and students. As more children of immigrants in Japan start attending Japanese universities, the popularity of these heritage languages in SALCs and the wider curriculum may increase.

Also of note is the absence of Japan’s indigenous languages, such as Ainu and the Ryukyu languages. These are featured at only one institution, and then only with the provision of learning materials. While not spoken by huge numbers across the country (Ainu was said to be spoken to some extent by only around 300 people in 2011; Teeter & Okazaki, 2011), these languages have important cultural significance, especially given their historic oppression (for more, see Heinrich, 2018; Siddle, 1996; Weiner, 1997). Also completely absent are sign languages such as Japanese Sign Language. While these may be being taught through other channels at some institutions, SALCs in Japan do not seem to be actively promoting these languages at present. Offering these kinds of languages could be a way for SALCs to attract a more diverse variety of students to their services, in addition to raising awareness about their presence in Japan, and countering narratives of homogeneity which downplay Japan’s cultural diversity.

Stance of SALC Coordinators to LOTE: Continuing Dominance of English

While there is significant support for LOTE among the responses, there are several instances in the data set which seem to suggest that the issue of supporting LOTE is one which is not strongly on the radar for coordinators at some institutions especially those in English-focussed SALCs. When asked about barriers to supporting LOTE in their SALCs, there was a tendency for the responses to reflect general barriers to SALL, rather than specific issues connected with LOTE, which may suggest a lack of engagement with the issue.

Similarly, when reporting their personal stance to the existing language policy in their SALC, there was a tendency for some participants from English-dominant SALCs to interpret questions about multilingualism quite narrowly, assuming that the main focus of the survey was the role of Japanese in English-focussed environments, even when the question explicitly used the term “languages other than English.” Although seven responses from these SALCs did address the issue of LOTE to some degree, four out of 12 responses focussed only on whether Japanese was permitted in the SALC, and one other simply affirmed the success of the English-only stance. The descriptions of language policy also reveal a preoccupation with the degree of Japanese permitted in an otherwise English space. This narrow focus on the relative use of English and Japanese could be regarded as evidence of the persistence of the double monolingualism of Japanese and English referred to by Murakawa (2018), despite evidence of coordinators’ enthusiasm to promote LOTEs in some SALCs.

Recommendations and Conclusion

This research has attempted to investigate the current provision for LOTE in SALCs across Japan.The major limitation of this study is its small size.Only 27 institutions in Japan are represented in the data set, and more detailed responses, in the form of interviews, would make for a more comprehensive understanding. No comparison is made between Japan and other countries, which could shed light on whether the situation in Japan is unique or reflected in other contexts. Nevertheless, this study is a valuable first step into this important aspect of self-access provision.

Overall, while over half the SALCs featured in the study do not cater for any language other than English or Japanese, the survey reveals that there is growing support for LOTE in SALCs across Japan, especially for global languages such as Chinese, French, and Spanish and regional languages like Korean. Other languages appear less often and may be limited to occasional culture-focussed events rather than active language study and use. Some, such as indigenous and sign languages, are hardly present at all. Given the linguistic diversity which the survey reveals to be present among staff at many institutions, and the likely presence of student users who speak various other languages, it could be argued that opportunities to promote different languages are being missed.

As many SALCs are run on small budgets with few staff, whose SALC role is often secondary to other academic duties, it can undoubtedly be challenging to cater for additional languages. There are also often valid reasons for some SALCs to focus exclusively on English, such as being affiliated to a faculty of English. Even in facilities where this is not the case, a lack of student demand may seem to be an understandable reason for not being able to devote precious energy and resources to LOTE provision. This is especially important given the crucial role of communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991) in self-access and the basic psychological need of relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2017) in sustaining motivation for language learning, and may be challenging with a low number of students learning the same language. However, low interest in LOTE should not be accepted as a simple fact, but as the result of the dominance in Japan of the narrative that English is the only language worth learning. Given this context, the case for studying LOTE may not have been properly heard by potential learners. While there is certainly movement in this direction, this study indicates that many SALCs have yet to embrace the role of LOTE ambassador. For those practitioners who are looking to increase LOTE provision in their SALCs, the following recommendations may be a useful starting point:

- Find out what languages are spoken in your SALC community (staff and students) and encourage those with other languages to share their knowledge and experience, in whatever forms they are willing to do so, such as making multilingual displays or running workshops or one-off events.

- Actively recruit staff and student staff with multilingual repertoires.

- Provide materials for multiple languages, including indigenous and sign languages, and display them prominently.

- Offer language learning advising for any language. As learning advisors support students to organize their learning and develop their autonomy as language learners, they do not have to be experts in a specific language to be a valuable resource for learners.

- Invite guest speakers with knowledge of other languages.

- Encourage students who are interested in learning LOTE to form a learning community and support each other’s learning (Hooper, 2020; Watkins, 2022).

- Revisit your SALC mission statement, and, if necessary, rewrite it to include an emphasis on multilingualism and LOTE.

While some of these initiatives may require more resources, in terms of time or budget, than are currently available, others may be easier to implement. Further research into linguistic diversity could examine the viability and effects of specific initiatives or investigate the wider contexts and attitudes to LOTE provision in more detail. Wherever we start, SALCs are important spaces for challenging the narrative about the dominance of English and making space for other languages, which in turn can improve the intercultural communicative competence of our learners, as they better understand Japan’s cultural and linguistic diversity.

Notes on the Contributor

Katherine Thornton is an associate professor and learning advisor at Otemon Gakuin University, Osaka. She is the director of E-CO (English Café at Otemon), the university’s self-access centre, and current president of the Japan Association of Self-Access Learning (JASAL). Her research focuses on multilingualism in self-access environments, and second language identities.

References

Adamson, J., & Fujimoto-Adamson, N. (2012). Translanguaging in self-access language advising: Informing language policy. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.37237/030105

Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (2019). Tagengo seikatsu jōhō [Living guides in multiple languages]. https://www.clair.or.jp/tagengo/

Hashimoto, K. (2000). ‘Internationalisation’ is ‘Japanisation’: Japan’s foreign language education and national identity. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 21(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256860050000786

Hashimoto, K. (2017). Japan’s language policy and the “lost decade.” In A. Tsui & J. Tollefson (Eds.), Language policy, culture, and identity in Asian contexts (pp. 25–36). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315092034-2

Heinrich, P. (2018). Revitalization of the Ryukyuan languages. In The Routledge handbook of language revitalization (pp. 455–463). Routledge.

Hooper, D. (2020). Modes of identification within a language learner-led community of practice. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 11(4), 301–327. https://doi.org/10.37237/110402

Imamura, Y. (2018). Adopting and adapting to new language policies in a self-access centre in Japan. Relay Journal, 1(1), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010120

Japan Association for Self-Access Learning (n.d.). Language learning spaces registry. https://jasalorg.com/lls-registry/

Kubota, R. (2002). The impact of globalization on language teaching in Japan. In D. Block & D. Cameron (Eds.), Globalization and language teaching. (pp. 13–28). Routledge.

Kubota, R., & Takeda, Y. (2021). Language‐in‐education policies in Japan versus transnational workers’ voices: Two faces of neoliberal communication competence. TESOL Quarterly, 55(2), 458–485. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.613

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Liddicoat, A. J. (2007). Internationalising Japan: Nihonjinron and the intercultural in Japanese language-in-education policy. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 2(1), 32–46, https://doi.org/10.2167/md043.0

Lie, J. (2001). Multiethnic Japan. Harvard University Press.

Maher, J., & Yashiro, K. (1995). Multilingual Japan: An introduction. In J. Maher and K. Yashiro (Eds.), Multilingual Japan (pp. 1–17). Multilingual Matters.

Miller, R.A. (1982) Japan’s modern myth: The language and beyond. Weatherhill.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (2022). 2020 Population census: Basic complete tabulation on population and households. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00200521&tstat=000001136464&cycle=0&year=20200&month=24101210&tclass1=000001136466&stat_infid=000032142708&tclass2val=0

Ministry of Justice (2022). Gaikokujin seikatsu shien porutaru saito. [A daily life support portal for foreign nationals]. https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/support/portal/index.html

Murakawa, K. (2018). Multilingualism in Japan’s language policy: A critical sociological analysis [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Toronto.

Murray, G., & Fujishima, N. (2016). Understanding a social space for language learning. In G. Murray & N. Fujishima (Eds.), Social spaces for language learning: Stories from the L-café (pp. 124–146). Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1057/978113730103.0023

Mynard, J., Burke, M., Hooper, D., Kushida, B., Lyon, P., Sampson, R., & Taw, P. (2020). Dynamics of a social language learning community: Beliefs, membership and identity. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788928915

Pearce, D. R. (2021). Homogenous representations, diverse realities: Assistant language teachers at elementary schools. The Language Teacher, 45(3), 3–9. https://jalt-publications.org/articles/26461-homogenous-representations-diverse-realities-assistant-language-teachers-elementary

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs of motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications. https://doi.org/10.1521/978.14625/28806

Siddle, R. M. (1996). Race, resistance and the Ainu of Japan. Routledge

Sugita McEown, M., Sawaki, Y., & Harada, T. (2017). Foreign language learning motivation in the Japanese context: Social and political influences on self. Modern Language Journal, 101(3), 533–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12411

Takahashi, C. (2022). Motivation to learn multiple languages in Japan: A longitudinal perspective. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/TAKAHA4839

Teeter, J., & Okazaki, T. (2011). Ainu as a heritage language of Japan: History, current state and future of Ainu language policy and education. Heritage Language Journal, 8(2), 251–269. https://doi.org/10.46538/hlj.8.2.5

Thornton, K. (2017, December 16). Nihongo kinshi? Language policy and practice in language learning spaces in Japan [Conference session]. Japan Association for Self-Access Learning Conference 2017. Chiba, Japan.

https://jasalorg.com/conferences/jasal-2017-conference-kuis/

Thornton, K. (2018). Language policy in non-classroom language learning spaces. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 9(2), 156–178. https://doi.org/10.37237/090208

Thornton, K. (2020). Student attitudes to language policy in language learning spaces. Japan Association for Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(2), 3–23. https://jasalorg.com/thornton-student-attitudes/

Tsuneyoshi, R. (2018). the Internationalization of Japanese education – “International” without the “Multicultural.” Educational Studies in Japan: International Yearbook, 12, 49–59. https://doi.org/10.7571/esjkyoiku.12.49

Ushioda, E. (2017). The impact of Global English on motivation to learn other languages: Toward an ideal multilingual self. Modern Language Journal, 101(3), 469–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12413

Watkins, S. (2022). Creating social learning opportunities outside the classroom: How interest-based learning communities support learners’ basic psychological needs. In J. Mynard & S. Shelton-Strong (Eds.), Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom: A self-determination theory perspective. (pp. 109–148). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788929059-009

Weiner, M. (1997) Japan’s minorities: the illusion of homogeneity, Sheffield Centre for Japanese Studies/Routledge series. Routledge.

Wongsarnpigoon, I., & Imamura, Y. (2020). Nurturing use of an English speaking area in a multilingual self-access space. Japan Association for Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(1), 139–147. https://jasalorg.com/journal-june20-wongsarnpigoon-imamura/

Wongsarnpigoon, I., & Imamura, Y. (2021). Exploring understandings of multilingualism in a social learning space: A duoethnographic account. In A. Barfield, O. Cusen, Y. Imamura, & R. Kelly (Eds.), The Learner Development Journal issue 5: Engaging with the multilingual turn for learner development: Practices, issues, discourses, and theorisations (pp. 74–91). The Japan Association for Language Teaching (JALT) Learner Development Special Interest Group. https://ldjournalsite.files.wordpress.com/2022/01/ldj-1-5-06-12.26-web-01.06-updated.pdf

Wongsarnpigoon, I., & Watkins, S. (2022, November 18). An event for embracing linguistic diversity in a self-access center [Conference presentation]. Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education’s 9th Lab Session, online. https://kuis.kandagaigo.ac.jp/rilae/lab-sessions/lab9/