Thomas Stones, Kwansei Gakuin University, Nishinomiya, Japan. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3849-550X

Stones, T. (2023). The 7-Day Challenge: Taking steps towards a learning habit Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(2), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.37237/140205

Abstract

For many English-language learners around the world, how to make meaningful progress outside of the classroom is an ongoing challenge. Many learners feel that they want to study on their own but lack the resources or knowledge on how to proceed effectively. Thus, this paper reports on an initial investigation into a seven-day independent learning challenge where learners were set the task of completing five independent learning tasks across a single week with the intention of establishing a habit of studying English. The study took place at a Japanese university with non-English majors and represented the culmination of a series of independent learning tasks. Results focus on the nature of tasks completed throughout the challenge as well as learners’ perceptions of it and the feasibility of independent learning tasks across the semester. Broadly feedback was positive, and findings suggest that learners felt they made progress with their English and in establishing a study habit. Recommendations for future research and applications to other classroom contexts are presented.

Keywords: independent learning, habit formation, learning tasks

One of the many challenges faced by English learners in English as a foreign language (EFL) contexts is gaining enough exposure to the language to make meaningful progress. Often classes may meet just once or twice a week, and learners need to juggle other commitments such as work, hobbies, family or studies. Also, for university students who are not English majors, their English classes make up only a small part of their required study, with most of their time spent on other subjects. Thus, part-time EFL learners are only in the classroom for around one to three hours per week. When this is compared to the amount of time required to make progress with a second language, it appears woefully insufficient. For example, Cambridge (2001) recommends around 200 guided study hours to advance one level on the CEFR scale. Similarly, studies on the progress on the IELTS test found that around 10 to 12 weeks of full-time study was required to move up half a band on average (Elder & O’Loughlin, 2003; Kang, et al., 2021). These figures are clearly all averages and depend on multivariate factors, but what is clear is that the amount of time most part-time EFL learners spend is well below what is necessary to make solid progress.

As such, it is essential for learners who want to improve to spend time outside of class developing their English skills. This could be through prescribed homework, but ideally, if learners can become autonomous, or as defined by Benson (2011, p. 58) to have “the capacity to take control of one’s own learning”, and therefore, as Ushioda (2011) puts it, reach their full potential, they will be more successful. To achieve this, Cotterall suggests five key principles that can guide the integration of autonomous learning into a curriculum, which include a focus on learner goals, the language learning process, authentic tasks, discussion and practice of learning strategies and reflection on learning (2000). Further, various models and approaches have been developed for the implementation of a program of self-directed learning. (See Isabeles Flores et al., 2022 for a description of various models.) In addition, Little (1995) notes the importance of in-class interaction between learners and the teacher as essential components in developing autonomy. This was supported by the data from reflective journals among Thai MA students who noted that in-class discussion and collaboration were essential in the development of autonomy as it led to adaptions in their out-of-class learning habits (Chinpakdee, 2022).

However, becoming truly autonomous can take some adaption, and learners need teacher support (Little, 1995). Some researchers have posited that autonomous learning may be less appropriate in Asia, due to a classroom culture that is heavily teacher-dominated (Nelson, 1995). The type of domination here is where the teacher drives all learning and learners complete only the tasks that they are given, irrespective of how suitable they are to their individual goals or weaknesses. However, some teacher support is essential for learners unused to driving their own learning. Indeed, quotations from students in Humphreys and Wyatt’s study supported this, with learners stating, “teachers should help us to set goals” and “teachers need to give more resources and useful material to practise” (Humphreys & Wyatt, 2014, p. 58). Warrington (2022) similarly found in a case study on self-access learning that Japanese learners only had a vague view of what independent learning was and lacked clear ideas about how to study independently. Littlewood (1999) warned against culturally based generalisations and proposed that elements within Confucian cultures would, in fact, support the implementation of autonomous learning, such as high achievement motivation for a collective goal and putting significant effort into self-betterment. He also predicted that East-Asian learners would have the same capacity as any other students but notes that their educational background may not have included many suitable opportunities.

Habit Formation

One key aspect to good autonomy is discipline and the development and maintenance of a habit of consistent study. There has been relatively little research in the field of language learning on habit formation. Research has tended to discuss metacognitive strategies and affective management (e.g., Chamot et al., 1988; Oxford, 1990). However, the psychology literature is a rich source of information on the development of study habits. A habit can be defined as a learned tendency to act automatically in a particular way in response to a cue (Verplanken & Orbell, 2021). These can be as simple as automatically opening your email, or perhaps more realistically YouTube, when sitting down at the computer, or more complex tasks, such as writing a journal entry for 15 minutes before going to sleep. This has obvious applications as a component of autonomous learning as if learners can establish an effective study habit, they will be better able to maintain independent study.

One way to begin the process of habit formation is to make a plan, or to use Gollwitzer’s term, ‘implementation intention’ (1993). Simply, this is a plan to do a specified action when a particular cue is met. This increases the likelihood of the desired action taking place, and, over time, the behaviour can be habitualised (Holland et al., 2006). Further to this, McCloskey & Johnson (2019) found that rewards, context stability and frequency were all found to increase the likelihood of a habit being formed. However, they also found that more complex tasks were less likely to become habits. This has implications for language learning as the act of studying is more complex than, for example, reading a newspaper. Nonetheless, it can be beneficial to set a consistent time or place for a new habit to be conducted, even for complex tasks, as the cueing effect of time and location can be powerful (Tappe et al., 2013). Additionally, it has been suggested that a positive attitude towards the desired outcome, in our case studying English, is a good predictor of the initial uptake of the behaviour and, therefore, subsequent habit formation (Verplanken & Orbell, 2022). For example, Courtois et al. (2014) found in a study of tablet use in high schools, that an initial positive attitude towards and intention to use the tablets led to higher likelihood of initial tablet usage. This ties in with motivation literature in language learning where there is strong support for more motivated learners to be more effective learners (Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2011).

In terms of how long it would take to form a habit, the figure of 21 days has become popularised from an original study by Maltz (1960) who found it took around 21 days for his cosmetic surgery patients to become used to their new appearance. However, this study in fact suggested that 21 days was a minimum, an important point that is often omitted. More recent research (Lally et al., 2009) suggests it can take anything from 18 to 254 days to form a habit. This research found that simpler tasks i.e., those which take less time and effort, such as drinking a glass of water every morning, were easier to automatise than more challenging ones, such as going for a run every other day. Lally et al. (2009) also found that skipping a day or two here and there made no discernible difference to ultimate habit formation.

The 7-Day Challenge: Description and Rationale

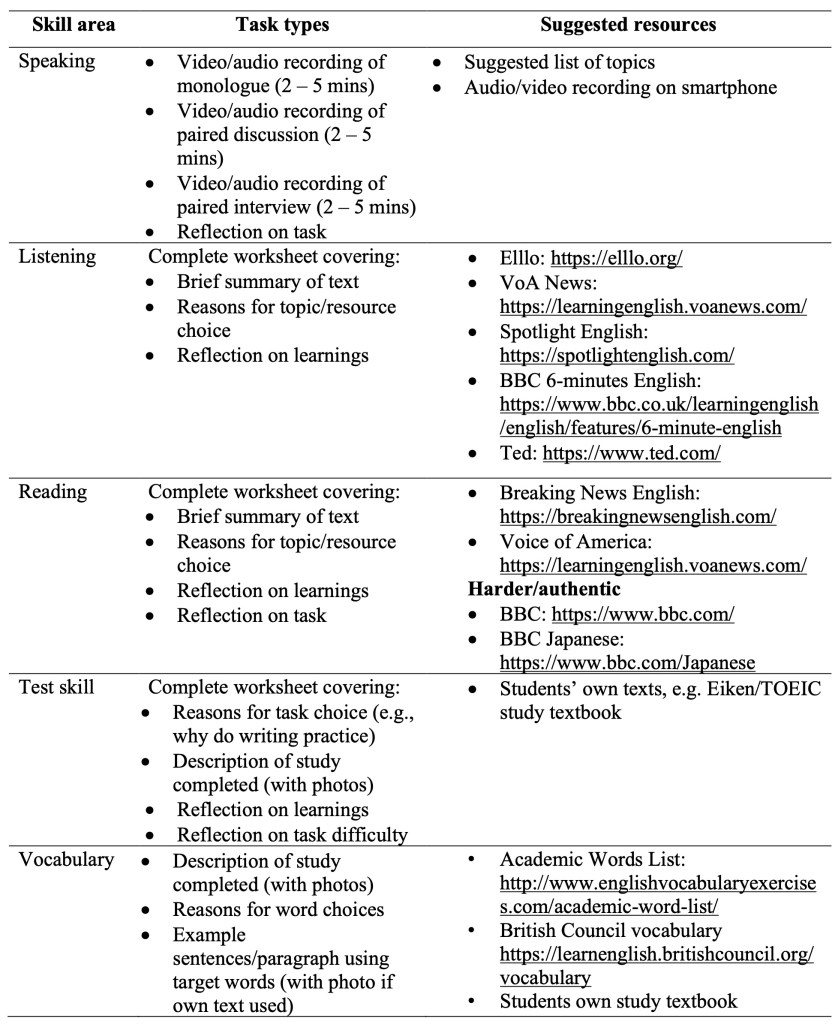

Thus, in order to develop skills in autonomous learning and begin to establish a learning habit, a programme of independent learning which culminated in the ‘7-Day Challenge,’ partly inspired by a well-known TED talk ‘Try Something New for 30 Days’ (Cutts, 2011), was implemented. The 7-Day Challenge itself began towards the end of a 14-week semester and required the learners to complete and submit five independent learning tasks of their choice over seven days. Although the literature above states that it takes considerably longer than seven days to fully establish a habit, course constraints meant that there was little time left before the end of the semester for a more ambitious time frame. Also, in the run-up to the main 7-Day Challenge, learners had completed a number of individual self-directed learning tasks. As such, the 7-Day Challenge was intended to bring the course to a close with an intensive focus on independent learning, with the hope that the experiences of the week, would serve as a trigger for future habit development. The tasks that made up the challenge were organised by skill area, and learners could choose to focus on one skill area only, for example, by doing five speaking tasks, or they could do a combination of tasks. A range of resources and task ideas were provided, but learners could use other resources or their own tasks. Table 1 summarises the skill areas, task ideas and resources. There was no writing option included as in a needs analysis on the skill areas learners most wanted to improve, none mentioned writing.

Prior to the 7-Day Challenge itself, there had been several tasks over the semester focused on independent learning. These included goal setting and completion of and reflection on individual independent learning tasks. For example, the whole class would complete the listening worksheet from Elllo.org but could choose their own topic from the site. This was followed by a speaking task, and various other one-off independent learning tasks over the following weeks. The purpose of these tasks was to familiarise the class to the resources and worksheets and to establish effective study methods, which is so often necessary for learners new to independent learning (Humphreys & Wyatt, 2014; Little, 1995; Littlewood, 1999) so as to allow them to make better-informed decisions when they were allowed more freedom. Additionally, familiarity with the tasks should ease the burden of the challenge itself, as it is easier to perform familiar tasks than learn new ones (Wood & Runger, 2016). As such, the process of introduction of resources prior to the 7-Day Challenge was similar to that of Iimuro and Berger (2010), which included awareness raising on autonomous learning, goal setting and action plan creation, regular task submission and reflection. Thus, the 7-Day Challenge represented an opportunity to consolidate this learning and attempt to trigger effective learning habits into the future.

Table 1

Summary of Independent Learning Tasks

During the 7-Day Challenge, tasks could be submitted at any point through the week, but learners were encouraged to submit regularly. They were also encouraged to make selections based on the goals they had set earlier in the course, but this was not required. As the challenge was introduced in class, learners could discuss their options and choices and also decide when and how they were to complete their five tasks, given their upcoming schedule that week, which should aid in habit formation (McCloskey & Johnson, 2019; Trappe et al., 2013). The name and the ‘novel challenge’ nature of the task was decided upon to generate interest and create a sense of shared challenge, which should help to foster motivation among learners in Japan (Littlewood, 1995). All tasks were uploaded to the university’s LMS. Following completion of five tasks, learners completed a questionnaire.

Project Aims

Rather than being set up as a controlled research project per se, this study was designed with both pedagogical and research aims. As such, it aligns with Burns’ (1999) description of action research in that it is small-scale, evaluative and reflective and has the aim of improving professional practice. This is the first time the challenge was attempted, so the main motivations were to examine the feasibility of completing this number of tasks in a week and explore the trends in task completion. Thus, the below aims were established:

- What task types do the learners tend to complete? Why?

- How long do learners spend completing each task?

- Do the learners feel that they made progress throughout the seven days?

- Do the learners feel that they were able to establish a study habit?

- How sustainable are independent learning tasks on a week-by-week basis?

Study Context

This study took place at a Japanese university in the Kansai region. The students were part of an English communication class of 26 students that met for 100 minutes per week across a 14-week semester. The main focus of the class was to develop general communication skills in English but had an autonomous learning component to it, as described above. Learners ranged in English proficiency level from A2 up to B2.

Methods

Due to the pilot-based nature of the study, and as there was no intention to explore relationships among variables, simple descriptive statistics were used to analyse survey responses. The survey included both closed and open-ended questions. The analysis of the qualitative data was inductive and followed the approach suggested by Thomas (2006), which involved first examining and reflecting on the qualitative responses, generating and refining categories and codes before relating the data to the research questions.

Results

Below, the initial descriptive statistics on task completion are presented. With a class of 26 students, there are a maximum of 130 possible independent learning tasks that could be completed. However, two students did not complete any tasks, leaving a potential total of 120 tasks that could be completed. Of this total of 120, 116 were submitted, at a submission rate of 96%. 57% of students chose to focus on a single skill for all five tasks, and 47% chose at least two different skill areas. 20 of the 26 students submitted the reflection questionnaire.

Figure 1 shows the skill areas that learners chose to focus on, based on an analysis of the 116 tasks submitted. As we can see, vocabulary and speaking were by far the most popular skill areas, followed by test study, reading, and finally, listening. The popularity of speaking and vocabulary was likely because this was a communication class, and learners frequently set goals that focused on improving speaking or being able to speak with foreigners. Also, learners often associated vocabulary learning with being able to speak more effectively as they felt that a lack of vocabulary was often a barrier to fluency, as noted in this quotation ‘I learned new vocabulary so I can speak English smoothly.’

Figure 1

Total Number of Task-Types Completed

Figure 2 shows the profile of the skill areas chosen by the thirteen learners who only focused on one area for all five tasks. Once again, speaking is prominent and is joined by test study as the most popular among this subset of students. It is interesting to note that there were only three instances of any students doing any form of test study aside from the four that focused solely on test study. This is likely because the ones that did focus on test study seemed to have quite a strong motivation for working towards their chosen test. Those that didn’t seemed to prefer focusing on more general tasks.

Figure 2

Profile of Single Tasks Chosen

As part of the questionnaire, students were asked to report how long they spent on each task. Results can be seen in Figure 3 and suggest that the amount of time varied considerably across the cohort, with some spending a little over one hour per week and one claiming to spend around 7.5 hours, although it is possible this learner misunderstood the question as this seems excessively long for the quality of work that was submitted. In general, it seems that most students spent around 30 minutes per task, which would account for two hours 30 minutes per week, although a good percentage also spent around one hour per task, leading to five hours of additional work per week.

Figure 3

Time Spent on Each Task

Sustainability Across the Semester

Students were asked to comment on how many tasks they felt they could complete in a typical week throughout the semester. Results can be seen in Figure 4. Most responded that two or three would be possible weekly across the semester. These students are not English majors, and this course accounts for one of over 20 credits worth of courses they are taking in a semester. As such, this seems a realistic and achievable total. It may also be influenced by their task choices and the amount of time spent on each, which, as shown above, was highly variable. Indeed, some learners even stated that they could do more than the five that they did in the week of the 7-Day Challenge, with one learner stating, ‘I often study English, so I am not difficulty the tasks.’

Figure 4

Number of Tasks Possible per Week

Qualitative Findings

The responses to the qualitative questions yielded a number of interesting findings which are presented below.

Reasons for Task Choices

As noted above, learners tended to focus more on speaking and vocabulary practice, with a small subsection focusing on test study and other areas. Below is an outline of the main themes that emerged from the open-ended questionnaire data. Many mentioned developing a perceived weak point, for example ‘speaking skills because I am not good at speaking.’ or ‘I focus on vocabulary and reading because these were the skills I was lacking.’

In addition, skill area choices were often related to a general lack in overall English ability, with learners commenting, for example that ‘Because in order to improve my English, I had to overcome my poor listening skills’ and ‘I focus on speaking. It’s because I want to increase my English skill.’ It seemed, however, that the learners who focused on test taking had more concrete goals in mind, either for improvement in the test score overall:

I focused on listening skill because previous TOEIC grade was the lowest in listening. To improve my grade, I need more listening skill. My goal is to score 700 on TOEIC test.

Or for other tangible goals, such as a future career that the test score could facilitate. ‘I focused on vocabulary and TOEIC score because I want to get high score for finding job.’

Habit Formation and Adaptions to Routine

While it is doubtful that seven days is enough to really establish a stable habit, a number of learners commented that they felt they had started the process of habit formation, commenting, for example, that ‘I get into the habit of studying English every day’ and ‘The benefit that I felt is getting into the habit of studying English daily.’ Further to this, learners also commented on how they had adjusted their daily routines in order to accommodate completing the tasks, for example stating ‘If I get up 15 minutes early in the morning, I can do all tasks’ and ‘I can complete the assignments on the train.’

Improvements in English Abilities

A number of learners noted that they could also make progress with their English skills. While one week is clearly not enough to make substantive gains, it is likely that the volume and regularity with which learners needed to complete tasks lead them to have a sense of making progress within the areas they had focused on as well as a sense of achievement in increasing the amount of English study they did. Indeed, it is likely they did make some progress in whatever area they chose, but at this point, it is unlikely to produce a significant effect if put to empirical test. Nonetheless, the fact that the sense of progress was created is good and will likely have a reinforcing effect and lead to continuation. Below are some comments that speak to the perception of gains made by students:

I feel these tasks can improved my English skills

I learned new words

I remember clearly 50 words.

I could understand how to solve the questions of EIKEN pre1

Also, after 5 days, my practice question scores are raised.

I improved because I can speak more fluently in English.

I felt to improve reading skills. My reading speed is a little speedy, I think.

Interestingly, one student combined some of the themes and commented, “To be honest, my listening skills didn’t change much, but I feel that I have acquired the habit of being exposed to English every day.”

Sustainability Across the Semester

While it could have been difficult for most learners to complete five tasks per week, a number of the participants felt that they could quite easily complete five or more per week across the semester. In particular, learners who spread out their learning appeared to benefit more, commenting for example, “I think the amount was just right, because I had time left to work on one thing a day, so I was able to work on it comfortably”.

However, many learners referred to the difficulty of juggling their multiple classes and other commitments:

I want to continue it. But there is a very busy week

I think it is [possible to complete] 3 or 4. I have classes, part time job, homework and playing with my friend.

I think I can do 2 tasks in a normal week. Because I have other class assignment.

Also, one issue with a challenge that takes place in a single week is that it can fall on a week where some learners are particularly busy, but others have more time, thus unfairly disadvantaging learners such as this one, who commented, “last week, I had a lot of assignments and presentations, so I didn’t have much time… But I tried hard.”

Discussion

Overall, it appeared that the 7-Day Challenge, in combination with the other independent learning elements of the course, was relatively successful. The completion rates were excellent, and the learners generally displayed a positive attitude towards the challenge. Despite the short time frame, they felt that they made progress with their English and with habit formation. It is likely that on completion of the challenge, any potential gains in habitual behaviour may be lost as learners slip back to their old ways, a common issue in habit maintenance (Verplanken & Orbell, 2022) due to factors such as time pressure, the task difficulty, or lack of will power (Wood et al., 2014). In addition, while the gains in English skills may be small, if the approach to study is maintained, they will likely lead to far more impressive gains in the future across a longer time span. Again, this would be an interesting area to follow up, but, as (Rutson-Griffiths & Rutson-Griffiths, 2019) note, the difficulty may come in accurately measuring any correlations between increased learning time and gains in general English proficiency.

In terms of the materials trialling, it appeared to go well, and a number of learners commented that the resources were useful, for example, “I think these site are very useful because I can learn English and at that time learn about topics that interest me.”

Recommendations and Reflections on Future Iterations

As frequently noted in the literature, many learners will need some level of scaffolding in terms of introduction to suitable resources (Benson, 2011; Humphreys & Wyatt, 2014; Little, 1995; Yang, 2020), and the initial weeks of preparation seemed to make the 7-Day Challenge all the more successful. This helped reduce the burden on learners of sifting through a raft of previously unseen resources as most had been encountered before. Additionally, the familiarity of previously attempted tasks may help them to form habits (Wood & Runger, 2016).

Setting goals, or implementation intentions (Gollwitzer, 1993), as well as deciding, as far as possible, a consistent time and place to complete the task due to the benefits of habit forming (Holland et al., 2006; McCloskey & Johnson, 2019) would be recommended also and seemed to be factors that assisted these learners although this was not a specific focus of the questionnaire or the setup of the 7-Day Challenge.

For the students on this course, it seems that around two tasks per week would seem ideal for most weeks, but with some able to complete more. This seems fair given the context of the study, and it would seem a balance of consistent, regular completion of independent tasks, alongside reflection and planning, could complement intensive challenges such as the 7-Day Challenge. This may need to be adapted to other contexts, but what is key is involving the learners in the process to establish what is possible. Indeed, some learners did state that they could do more tasks, so if course credits are involved, learners who do complete extra tasks should be credited in some way. Of course, intrinsically motivated students would tend to regard the tasks as rewarding enough (Kruglanski et al., 2018), but giving extra credit to these students would be an additional bonus.

Consideration also needs to be given to when and how often similar intensive learning challenges may be used. They could be used, as was the case here, at the end of a programme of study, but could easily be used where natural breaks in a course occur, or at multiple points throughout a course, though attention needs to be given to commitments learners might have on other courses. Integrating in-class discussion following the completion of individual tasks certainly seemed to help develop a sense of collaboration across that class and allows learners to share approaches and impressions of materials, although this was not a focus of the questionnaire. This applies to both individual tasks and when preparing for and reflecting on the main 7-Day Challenge itself and has strong support in the literature (Benson, 2011; Chinpakdee, 2022; Little 1995).

Limitations and Future Directions

First and foremost, the biggest limitation of this study is its small scale. While only intended as a pilot, it still lacks a rich data set, so expanding both the time frame and depth of data collection, if not necessarily the sample size to allow for a deeper analysis of the target population (Cresswell & Cresswell, 2018). Furthermore, in order to focus on more effective habit development, a longitudinal study with multiple points of data collection would shed light on habit formation and stability, in particular, once the requirement to submit tasks was removed. A pre-post design would also shed light on the gains made to English skills, but this would be complicated by the challenge of measuring gains to the specific skill areas that learners chose to focus on, so a comprehensive assessment of English proficiency would be necessary.

To conclude, the 7-Day Challenge seems to have been a success, though more thorough empirical investigation is necessary to ascertain the gains made. However, the learners viewed the task positively, and the challenge-based nature helped garner a sense of shared challenge and likely improved motivation.

Notes on the Contributor

Thomas Stones currently teaches English at Kwansei Gakuin University in Japan. His research interests include self-directed learning, assessment validation, especially Rasch-based methods, as well as listening and discussion skills development. He has presented and published on all of these areas.

References

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching autonomy (2nd Ed.). Routledge.

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge University Press.

Cambridge, (2021). Guided learning hours. https://support.cambridgeenglish.org/hc/en-gb/articles/202838506-Guided-learning-hours

Chamot, A. U., Küpper, L., & Impink-Hernandez, M. V. (1988). A Study of learning strategies in foreign language instruction: Findings of the longitudinal study. Interstate Research Associates.

Chinpakdee, M. (2022). Using learning journals to promote learner autonomy. ELT Journal, 76(4), 432–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccab056

Cotterall, S. (2000). Promoting learner autonomy through the curriculum: Principles for designing language courses. ELT Journal, 54(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/54.2.109

Courtois, C., Montrieux, H., De Grove F, Raes, A., De Marez, L., & Schellens T. (2014). Student acceptance of tablet devices in secondary education: a three-wave longitudinal cross-lagged case study. Computers in Human Behaviour, 35, 278–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.017

Cresswell, J. W., & Cresswell, D. J. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. (5th Ed.) Sage.

Cutts, M. (2011, July). Try something new for 30 days [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/matt_cutts_try_something_new_for_30_days

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and researching motivation. (2nd Ed.) Routledge.

Elder, C., & O’Loughlin, K. (2003). Investigating the relationship between intensive English language study and band score gain on IELTS. In R. Tulloh (Ed.), International English Language Testing System (IELTS) research reports, volume 4 (pp. 208–254). IELTS Australia Pty Limited. https://www.ielts.org/for-researchers/research-reports/volume-04-report-6

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1993). Goal achievement: the role of intentions. European Review of Social Psychology, 4(1), 141–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779343000059

Holland, R. W., Aarts, H., & Langendam, D. (2006). Breaking and creating habits on the work floor: a field-experiment on the power of implementation intentions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(6), 776–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.11.006

Humphreys, G., & Wyatt, M. (2014). Helping Vietnamese university learners to become more autonomous. ELT Journal, 68(1), 52–63. https://doi:10.1093/elt/cct056

Iimuro, A., & Berger, M. (2010). Introducing learner autonomy in a university English course. Polyglossia, 19, 127–131. https://en.apu.ac.jp/rcaps/uploads/fckeditor/publications/polyglossia/Polyglossia_V19_Iimuro_Berger.pdf

Isabeles Flores, S., Cass Zubiria, M. M., & Sebire, R. H. E. (2022). Processes employed to introduce autonomous learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 13(4), 426–441. https://doi.org/10.37237/130404

Kang, O., Ahn, H., Yaw, K., & Chung, S-H. (2021). Investigation of relationships between learner background, linguistic progression, and score gain on IELTS. https://www.ielts.org/for-researchers/research-reports/online-series-2021-1

Kruglanski, A.W., Fishback, A., Wooley, K., Bélanger, J.J., Chernikova, M., Molinario, E., & Pierro, A. (2018). A structural model of intrinsic motivation: on the psychology of means-end fusion. Psychology Review, 125(2),165–182. https://doi10.1037/rev0000095

Lally, P., van Jaarsverld, C. H. M., Potts, H. W. W., & Wardle, J. (2009). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), 998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Little, D. (1995). Learning as dialogue: The dependence of learner autonomy on teacher autonomy. System, 23(2), 175–181.

Littlewood, W. (1999). Defining and developing autonomy in East Asian contexts. Applied Linguistics, 20(1), 71–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/20.1.71

Maltz, M. (1960). Psycho-cybernetics. Prentice Hall. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

McCloskey, K., & Johnson, B. T., (2019). Habits, quick and easy: Perceived complexity moderates the associations of contextual stability and rewards with behavioral automaticity. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1556. https://doi10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01556

Nelson, G. L. (1995). Cultural differences in learning styles. In J. M. Read (Ed.), Learning Styles in the ESL/EFL Classroom (pp. 3–18). Heinle and Heinle.

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language Learning Strategies: What every teacher should know. Newbury House.

Rutson-Griffiths, Y., & Rutson-Griffiths, A. (2019). The relationship between independent study time, self-directedness, and language gain. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 11(1), 24–39. http://doi.org/10.37237/110103

Tappe, K., Tarves, E., Oltarzewsk,i J., & Frum, D. (2013). Habit formation among regular exercisers at fitness centers: An exploratory study. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 10(4), 607–613. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.10.4.607

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analysing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Education, 27(2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748

Ushioda, E. (2011). Why autonomy? Insights from motivation theory and research. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 5(2), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2011.577536

Verplanken, B., & Orbell, S. (2022). Attitudes, habits and behavior change. Annual Review of Psychology, 73, 327–352. https:// doi/10.1146/annurev-psych-020821-011744

Warrington, S. D. (2022). Exploring student perceptions of self-access learning for active learning: A case study. SiSAL Journal, 13(1), 108–128. https://doi.org/10.37237/130106

Wood, W., Labrecque, J. S., Lin, P. Y., & Runger, D. (2014). Habits in dual process models. In J. W. Sherman, B. Gawronski, & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual process theories of the social mind (pp. 371–385). Guilford

Wood, W., & Runger, D. (2016). Psychology of habit. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 289 – 314. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033417

Yang, F-Y. (2020). EFL learners’ autonomous listening practice outside of the class. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 11(4), 328–346. https://doi.org/10.37237/110403