Colin Mitchell, Reitaku University, Chiba, Japan

Mitchell, C. (2023). Supporting the transition to self-directed learning in ESL: A coaching intervention. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(2), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.37237/140204

Abstract

Self-access language centres (SALCs) utilise self-directed learning, which allows learners to set their own learning goals and make their own learning choices. While this approach can benefit language learners, it can also be intimidating for those not used to autonomous learning. To help learners transition from teacher-directed to self-directed learning, various interventions such as coaching, counselling, mentoring, and advising can be used. These interventions can be effective in helping learners become more self-directed, but it is important to review and consider the learner’s expectations when implementing them. This paper analyses data from a one-on-one coaching intervention between an English-speaking coach and five Japanese participants using English as a second language to explore the factors contributing to the intervention session’s perceived success.

Keywords: coaching, self-directed learning, language learner autonomy, interventions

Language learning facilities with self-access language centres (SALCs) utilise self-directed learning, a humanistic approach that helps learners make their own learning goals and choices (Hiemstra, 2013; Knowles, 1975). Self-directed learning has been adapted to the SALC to develop language learner autonomy. The concept of learner autonomy, defined as the ability of language learners to take control of their own learning process, set their own goals, select appropriate learning strategies, and evaluate their own progress, is drawn from previous literature (Benson, 2011; Dam, 1995; Little, 1991; Oxford, 2011) and supported by SALC needs analysis literature (Takahashi et al., 2013; Thornton, 2013).

While the literature mentioned above suggests that self-directed learning benefits the learner, several issues occur when learners are not accustomed to this autonomous learning style. Learners may not understand how to use the SALC due to a history of learning under direct teacher supervision (Croker & Ashurova, 2012), resulting in limited SALC usage due to feelings of anxiety and intimidation (Horai & Wright, 2016). Therefore, learners need to go through a transition from teacher-directed learning to self-directed learning.

There are various methods to support learners’ transitions, which are seen as interventions. These interventions may include setting specific goals, introducing effective language learning strategies, encouraging learners to self-assess their skills, providing feedback and reflection opportunities, offering a variety of resources, and creating a supportive community. By conducting a successful intervention, language learners can easily transition to a self-directed learning style and improve their learning outcomes.

This paper explores how five learners perceive interventions in a second language. These interventions have been referred to as coaching, counselling, mentoring, or advising, and the techniques often blend. The article discusses interventions in the literature review and applies them to language learners transitioning from teacher-directed to self-directed learning. However, these interventions are not limited to academia; this paper also draws on life and corporate coaching research.

Literature Review

Terminology for Interventions

Interventions encompass various terms, including counselling, mentoring, advising, and coaching, each with unique nuances that distinguish them while having commonalities. For example, person-centred counselling (PCC) is a type of humanistic counselling that concentrates on developing the individual in a non-directive way. PCC involves self-directed counselling, aiming to take action towards a specific goal (Colledge, 2002). However, Carson and Mynard (2012) dismissed the label ‘counselling’ because it implies the person seeking counselling is going through pain or struggle. Instead of counselling, Kato and Mynard (2016) use the term ‘advising’, which they define as “the process of helping someone to become an effective, aware, and reflective language learner” (p. 1) through “intentionally structured dialogue designed to promote learner autonomy” (Mynard et al., 2018, p. 55).

These types of interventions can carry many benefits in various instances. A recent study into academic coaching by Griesheimer (2022) showed that it could be used to support students adapting to life issues, such as adapting to self-directed learning in university life. The study also showed that academic coaching supported students suffering from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to graduate successfully from university. In ESL, Shelton-Strong (2022) suggested that language learning “can cause immense satisfaction and terrible frustration, in equal measure” (p. 965) and therefore, language students also could benefit from the support coaching provides.

Interventions Across Cultures

This paper refers to the interventions as ‘coaching’, which shares similar traits to PCC and advising but is defined as a non-direct focus. Coaching is defined as client-centred, where the coach and client are equals, and the outcome is focused on transformation and action (Rogers, 2016). Coaches pose questions to the client, allowing them to reflect on their answers and unwrap the possibilities to move closer to their goal. The reason for using the term coaching is to avoid the participants from expecting any direct advice given within the session.

Intercultural coaching can present challenges if coaching principles are not adapted to new cultures (Abbott et al., 2006). For instance, Nangalia and Nangalia’s (2010) study on Japanese corporate and life coaches found that clients expected advice rather than questions due to their culture’s social hierarchy. Conversely, Lam (2016) discovered in their corporate and life coaching study that Hong Kong people with a non-Western background but influenced by Western culture adapted to coaching more readily. Plaister-Ten’s (2009) research on intercultural corporate coaching clients concluded that cross-cultural coaching might never have a clear, agreed-upon outcome, but education and awareness are critical. As such, coaches should be clear on coaching principles, as highlighted by Nangalia and Nangalia (2010) and Lam (2016), and consider learners’ needs and prepare them thoroughly before coaching sessions (Carson & Mynard, 2012).

To support language learners facing challenges related to anxiety, motivation, and confidence, Shelton-Strong (2020) used self-determination theory (SDT) as a framework since it caters to students’ fundamental psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. SDT explains that satisfying the desire for competence leads to a sense of mastery and accomplishment, while the need for relatedness satisfies the emotional and social need for connection and respect from others (Ryan & Deci, 2018). Autonomy, defined by Ryan and Lynch (1989) as the ability to act in ways consistent with one’s interests and beliefs, is a core concept of SDT. Interventions that enhance autonomy, competence, and relatedness, such as offering options, constructive criticism, and social support, can help promote internalisation and growth.

SDT can aid learners in developing and maintaining a sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in their academic life. Goal setting and reflection can facilitate self-motivation and help individuals identify external norms and values that conflict with their sense of self, thus promoting greater autonomy. Kato and Mynard (2016) introduced transformational advising as an approach that helps learners become aware of anxiety, self-doubt, or dependency issues. It blends elements of PCC, coaching, and advising to focus on the learner as a resource and allow them to find their own solutions. However, the researcher did not use the term transformational advising in this study to avoid using the term ‘advice’ since the participant may believe they are getting direct advice. Nonetheless, Carson and Mynard (2012) have demonstrated that transformative advising is effective in a Japanese foreign language learning context.

Interventions in a Second Language

When considering intercultural interventions, there is a chance that not everyone shares the same native language. If one of the participants is using their second language, then there is a potential for a communication breakdown. Thornton (2012) discovered that advising in the advisee’s second language resulted in slower-paced sessions, an enhanced sense of achievement, and frustration when communication became difficult. Thornton determined that for successful advising sessions in the advisee’s second language, the advisee must prepare for the session structure ahead of time. It is also recommended that sessions be supported with written reflections as it is often easier for second language users to digest written dialogue than spoken language. Visual aids such as drawings and diagrams made by the advisee in the session serve as a clear reflective tool. These written reflections and visual aids can be combined with session records through the advisee’s notes and audio recordings. Finally, it is necessary to provide language support for the advisee to communicate effectively by allowing access to dictionaries or common meta language. Kato and Mynard (2016) noted that lower-proficiency English speakers may feel more comfortable speaking in their native language. Even high-proficiency speakers still might not have the metalanguage for coaching and can revert to their native language when discussing certain topics. Kato and Mynard suggested that when fluent advisees switch between languages, it could indicate an internal conflict. Therefore, intercultural interventions must consider the language abilities of all involved, and providing language support, written reflections, and visual aids can enhance the effectiveness of advising sessions in a second language.

Methods

In this study, five participants were coached over three sessions using a semi-structured framework that used coaching to develop self-awareness. To provide an empirical basis for our analysis, a one-on-one coaching intervention was conducted at a language university in Japan between an English-speaking coach and Japanese participants using English as a second language. This exhortative study aims to determine the understanding of the intervention process through English as a second language. Therefore, this study explores the following questions:

- How did the participants perceive the coaching session before their first session?

- How did the participants perceive the coaching session during their sessions?

- How did the participants feel about the coaching session after each session?

The session’s structure began by focusing on the participant’s goals and the reality of their situation. Then it allowed the participant to explore the options for achieving their goals and changing their situation for the better. Finally, the sessions aimed to motivate the participant to make sustainable plans for change.

Participants

This study contains two types of participants, the coach and the coachee. The coach is the author, an English speaker and a language educator, and is known by the participants as such. The coach is ICF-trained at the Associate Certified Coach level and has 82 hours of ICF coaching education, with 10 hours of coaching under the guidance of an ICF-qualified mentor. The coach also has over 100 hours of coaching experience with clients worldwide, specialising in supporting clients adapting to other cultures.

The coachees in the study were Japanese native-speaking adults with proficiency in English as a second language. It is unknown at what level of proficiency is needed for coaching to be successful. However, using the Japanese international company Rakuten as a reference, we see that the company uses English as its internal language and requires a TOEIC score of 600 for fixed-term employment and 800 or more for full-time employment (Rakuten, n. d.). Therefore, someone with a TOEIC score of 600 might struggle linguistically in a coaching session. In contrast, someone with a TOEIC score closer to 800 is more likely to have the linguistic capabilities to participate in the coaching process since they have the potential to be part of an international company using English. However, since the TOEIC test has no direct correlation to interventions, it is unclear how the score will directly affect the participant.

The coachee participants were all studying at a language university in Japan. This study did not measure cultural competency as it focused on language ability as the variable. Coachee eligibility was determined by a range of TOEIC scores, including a mix of participants with low scores (400) and high scores (over 600), with the highest being 700. The range of low and higher scores ensured varying levels of English proficiency for the analysis; however, it should be noted that none of the participants had a TOEIC score of 800 or higher. This may contribute to how they perceived the coaching sessions.

Application posters were distributed around the university, informing that there was a study for coaching with a link to the application form. Ten participants applied for the study, but only five were accepted. Reasons for rejection were that two had a working relationship with the researcher, which would have broken university ethics policy, one participant was deemed to have an English proficiency too low, and two had TOEIC scores too close to the other participants.

The five who were accepted were three males and two females. They were selected based on their TOEIC scores, which gave a range from low intermediate (400), intermediate (450, 585) and high intermediate English proficiency (610, 700). These have been coded as LI1 for low intermediate, I1 for intermediate 1, I2 for intermediate 2, HI1 for high intermediate 1, and HI2 for high intermediate 2. All the participants completed the coaching sessions, but I1 did not complete the final questionnaire.

Design

This study utilises a single-group pre-test post-test design to evaluate the perceptions of a coaching intervention on the participants. Participants completed a pre-coaching questionnaire before taking the coaching sessions and a post-coaching questionnaire after the final session. The coaching sessions were transcribed and monitored by the researcher. At the end of each session, the participants were asked to reflect on the session. The coaching intervention consisted of three weekly one-on-one, one-hour coaching sessions with a trained coach, focusing on goal setting. The primary research aim was to discover the perceptions and feelings of the coaching sessions.

Procedure

Pre-Coaching Data Collection

Demographic quantitative data were collected using a bilingual Google form questionnaire. This data collection included an explanation of the study and the data collection methods, i.e., recordings and surveys. Contact information was collected, as well as the participating coachees’ TOEIC scores. This information was used to contact the participants and match them to their varying levels LI1, I1, I2, HI1, and HI2. The native languages of the participants were collected as there are many nationalities at the university, and the study only looked at Japanese participants. Finally, the participating coachees were asked to explain what they thought coaching was. This question allowed the researcher to determine if the participants understood coaching before beginning the sessions. If they already had a detailed understanding of coaching, it may have been easier for the participant to comprehend the coaching process despite their language level.

Participating coachees eligible for the study were contacted directly by the researcher, and the session structure was explained to them in both English and their native language, Japanese. After the participants confirmed their understanding and agreed to take part in the research, coaching sessions were scheduled.

Coaching Session Data Collection

The participating coachees attended three one-hour semi-structured coaching sessions conducted by the researcher, which focused on goals, reality, options, and will (GROW – Whitmore, 2017) and used transformational ALL techniques such as repeating, summarising, empathising, metaphor, powerful questions, sharing experience, complementing, silence and promoting accountability (Kato & Mynard, 2016). The face-to-face coaching sessions were conducted in the researcher’s first language and the participants’ second language, English. Recordings of the sessions were made, and the participants were asked before and after the session if they consented to the recording. These recordings were transcribed for data analysis.

Post-Coaching Data Collection

After the final coaching session, participating coachees filled in a bilingual post-coaching Google form questionnaire. The aim was to discover if the coaching was perceived to be successful and whether the participants understood the coaching process and were satisfied with the outcomes. This mixed-methods data collection questionnaire included multiple questions with yes/no choices and a space for participants to give details about their answers.

The first section of the questionnaire focused on coaching goals. The first question asked if the sessions helped the participant realise their goal, and the second question asked if coaching helped them find the best course of action for achieving their goal. The final question of the section asked the participants to explain how they would continue to work on their goals.

The second section focused on coaching language. This section contained open-ended questions which asked about the difficulties of using English in a coaching session and the advantages of using Japanese in a coaching session. This section also asked participants if they would prefer to be coached in Japanese or English if they had a serious issue.

The final section focused on coaching culture and also asked open-ended questions. The first question focused on hierarchy and asked if the participants preferred an older or younger coach. The second question asked whether the participant preferred more direct advice in the coaching session. Finally, the last question concerns the power dynamic and asks if it was important that the coach was a language teacher.

Limitations

Several limitations to this study should be considered when interpreting the results. Firstly, the small sample size of five participants may limit the generalizability of the findings. While the participants were selected based on a range of English proficiency levels, they all studied at the same language university in Japan. They, therefore, may not be representative of other Japanese adults with proficiency in English as a second language.

Using self-report measures for data collection may introduce response biases, such as social desirability or acquiescence bias. Participants may have been inclined to respond in a way that they perceived as favourable to the researcher rather than providing an accurate reflection of their perceptions and feelings about the coaching sessions.

Finally, the study utilised a single-group pretest-posttest design, which may limit the ability to draw causal inferences about the effectiveness of the coaching intervention. While the study aims to evaluate the participants’ perceptions of the coaching sessions, it does not account for potential confounding variables or alternative explanations for any observed changes in perceptions or feelings.

Data Analysis

The research sought to understand how the coaching sessions worked in a second language and whether they were perceived as successful. This study is still in its infancy, and there is much to learn from the results. Therefore, the practical first step of data analysis is to identify potential themes (Lyons & Coyle, 2016). The coaching transcripts were studied using thematic analysis.

- How did the participants understand the coaching session before their first session?

Potential participants watched a bilingual video presentation explaining the coaching process. The coaching process was outlined in the video presentation as follows:

- Participants meet with a coach for 1 hour once a week, three times.

参加者は週1回1時間、3回にわたってコーチと面談します - In the first session, the coach will ask you about your goals.

最初のセッションでは、コーチがあなたの目標をお聞きします。 - In the second session, the coach will ask you about your choices for reaching those goals.

2回目のセッションでは、その目標に到達するための選択肢をコーチがお伺いします - In the final session, the coach will ask you about your plans for achieving your goals.

最終セッションでは、コーチが目標達成のための計画についてお聞きします - After the final session, participants are asked to give feedback on the coaching.

最終セッションの後、参加者にコーチングについてのフィードバックをお願いしています

Before the coaching sessions and after watching the video, the participants were asked to define coaching in their own words. Most believed it was a teaching process or helping them improve their language skills. These initial results were interesting because the researcher is a language teacher and their coach. However, the research never drew connections between the coaching process and language education. The participants were free to decide their own goals. This does not affect the results because improving language skills is a valid goal for a coaching session. It is also worth noting that these participants are university language students, and whether the researcher is their language teacher or not, improving their English may be their coaching goal.

- How did the participants perceive the coaching session during their sessions?

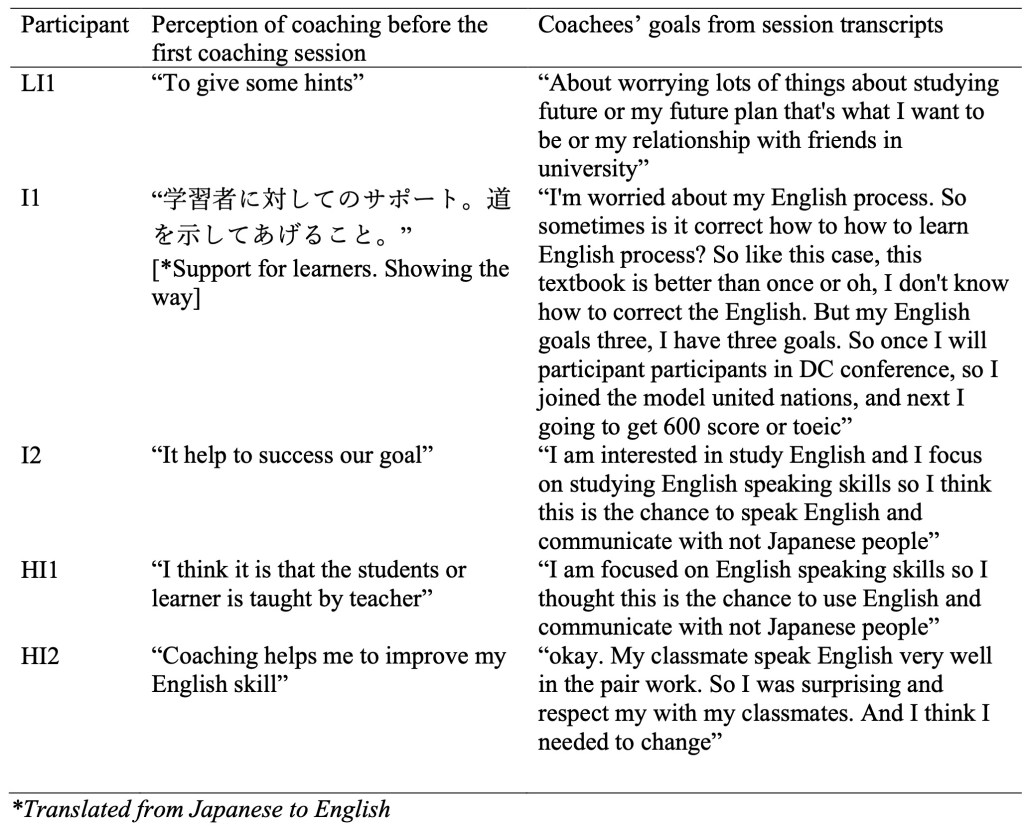

Table 1 shows how participants defined a coaching session before taking the session and the goal of each participant taken from the first session. This data analysis aims to understand how the participants perceived their goals and if there were any limitations.

Table 1

Perception of Coaching by the Participants Before and During the Coaching the Session

- How did the participants feel about the coaching session after each session?

At the end of each coaching session, the participants were asked to share their feelings about the sessions. These were coded into positive and negative perceptions about the session and perceptions about themselves. This data analysis of the pre-and post-coaching sessions and the transcribed data collected during the coaching sessions aim to understand how the coaching affected the participants and the goals of the sessions.

From the data in Table 1, it appears that most participants had a positive perception of coaching before their first session. However, there were some differences in how they defined coaching, with some participants viewing it as a teaching process and others as a support system to help them achieve their goals. There are some interesting connections when comparing the participants’ initial perceptions of coaching to their goals for the coaching sessions. For example, participant LI1 initially saw coaching as providing hints, and their goal was to discuss worries about their future plans and relationships. This suggests that they may have viewed coaching to receive guidance and support in dealing with their concerns.

Similarly, participant I2 viewed coaching as a way to help them achieve their goals, and their session goal was to improve their English-speaking skills by communicating with non-Japanese people. This suggests that they saw coaching as a tool that could help them reach their objectives.

These findings highlight the importance of understanding participants’ perceptions of coaching and how they align with their goals. It also underscores the need for coaches to clarify the purpose and scope of coaching sessions so that participants understand what to expect and how they can best use the coaching process to achieve their desired outcomes. Only LI1 focused on university life more than studying language. LI1 did not fill in the post-coaching questionnaire, and it is unknown if this participant was satisfied with the coaching process.

Results and Discussion

During the Coaching Sessions

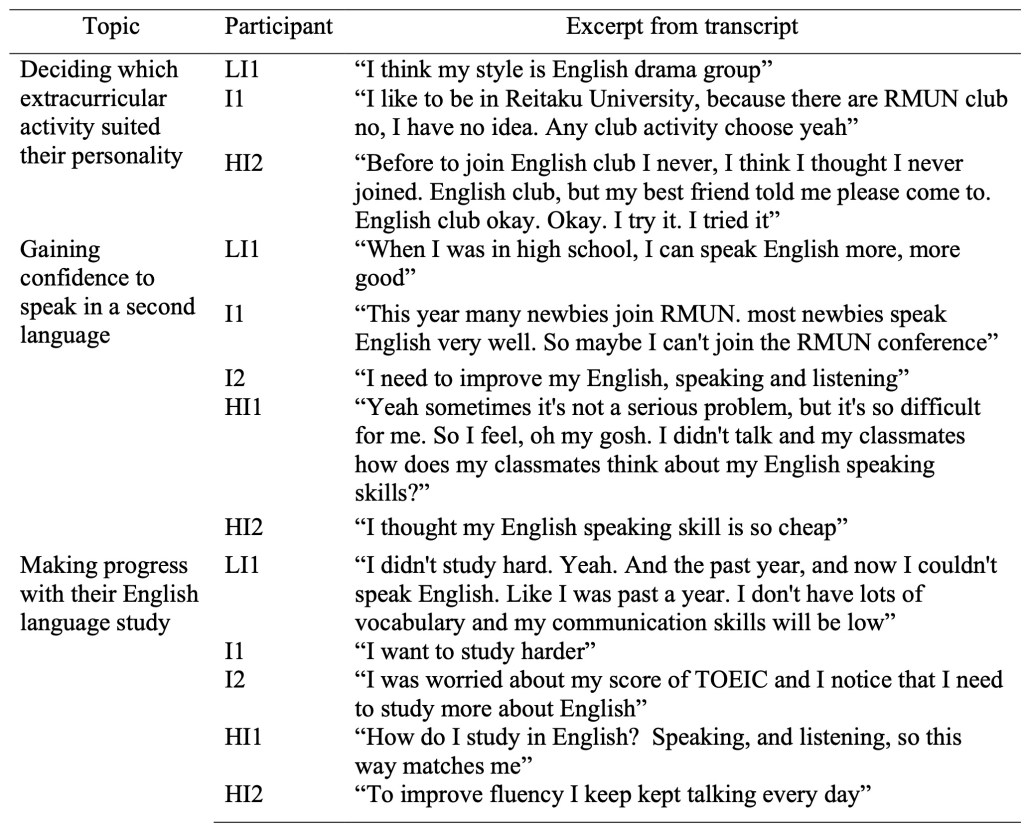

The participants’ topics fell into the following themes: deciding which extracurricular activity suited their personality, gaining confidence to speak a second language, and making progress with their English language study. Table 2 shows the theme with the participant’s responses.

Table 2

Participants’ Coaching Topic With a Direct Excerpt as an Example From the Session

One theme that was true for all the participants was gaining confidence in speaking English as a second language and making progress with their English language study. This matches the participants’ goals and initial perceptions of coaching. On the other hand, LI1, I1 and HI2 discussed extracurricular activities, particularly LI1 and I1. LI1 focused more on choosing a group to match their personality without having a clear goal. I1 had a much clearer goal, as seen in Table 1. HI2 talked about extracurricular activities but focused more on language learning. This led to the topic shifting more toward English language learning.

At the end of the third coaching session, the participants were asked about their perceptions of the session. LI1 concluded that the safe place was important for them to be “honest” and have their opinion accepted, allowing them to understand what they want. I1 also felt “satisfied” because they could express their thoughts. HI2 felt “comfortable” in the coaching session when previously they had felt anxiety about speaking English in conversational situations. I2 expressed a “new point of view” after the session, and they understood where their “trauma” stems from. HI1 also shared a new point of view about themselves and coaching. HI1 acknowledged their misconception of the coach as a teacher and recognised that the coaching “style is different” to teaching.

Post-Coaching

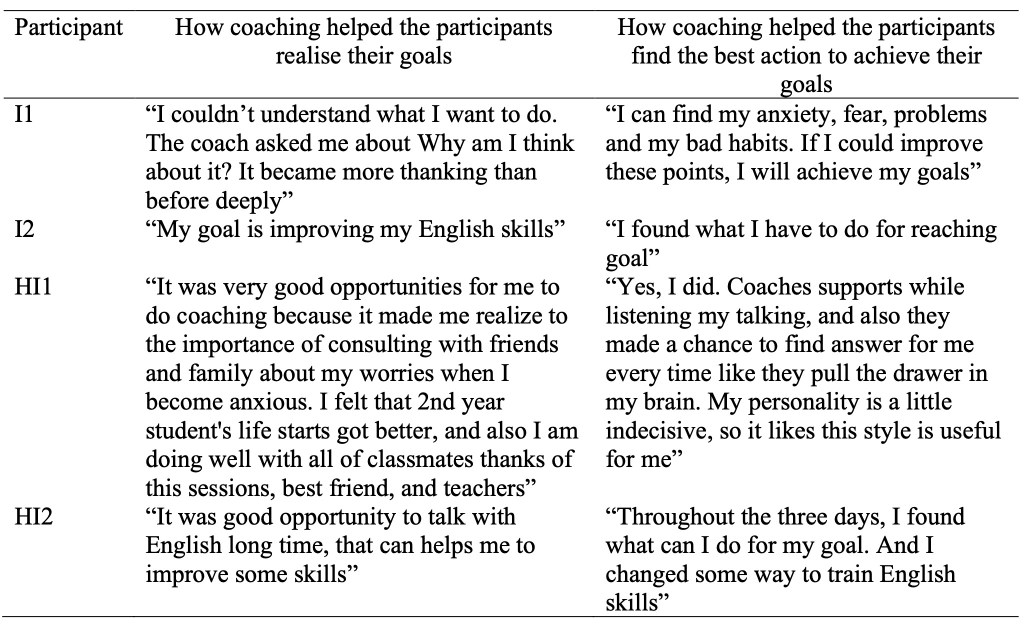

Table 3 shows the coachee responses taken from the post-coaching questionnaire. It reveals how coaching helped the participants realise their goals and find the best action to achieve them. All the participating coachees perceived that the coaching sessions helped them realise their goals. When asked to give details about their answer, I1 stated that they initially could not understand what they wanted to do, and through the coaching, they could think more deeply about their goal. The participating coachees also perceived the coaching sessions to help them find the best action for their goals. All the coachees stated they had discovered an issue about themselves and a technique for overcoming it. I1 described the process as pulling a drawer in their brain and finding what they needed to do inside. They concluded by revealing that they were naturally indecisive, but this coaching process suited their needs.

Table 3

How Coaching Helped the Participants Realise and Find the Best Action to Achieve Their Goals

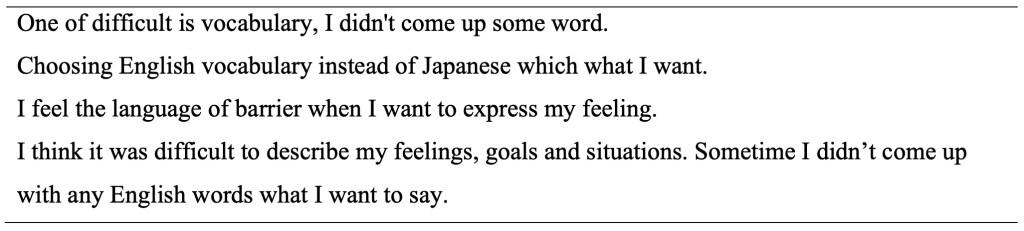

Language Difficulties Felt by the Participants

During this study, the participants felt the benefits of coaching in English as a second language but also some dissatisfaction shown in Table 4. The language barrier was an issue with the participants despite the coach being a language teacher. In particular, the coachees mentioned that it was difficult to come up with the vocabulary, especially when expressing their feelings.

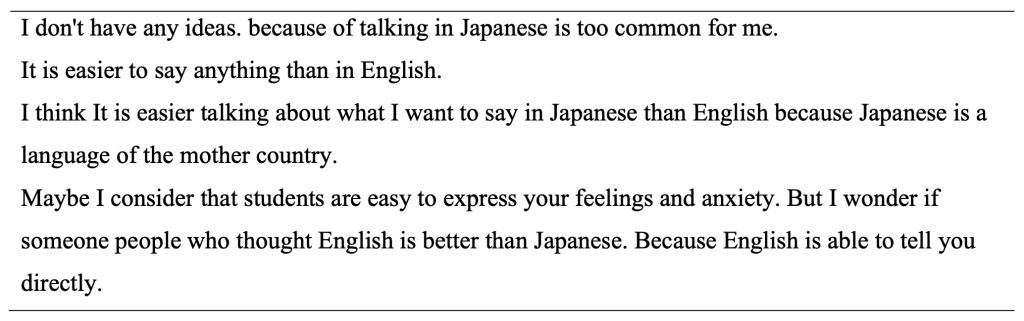

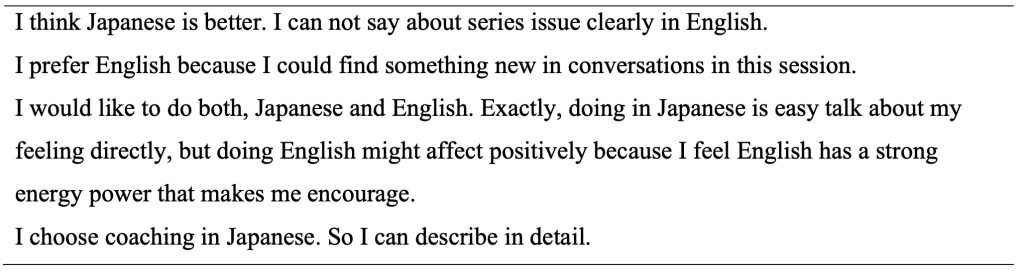

The participants recognised that having the sessions conducted in their native language would have been easier for them to express themselves, as seen in Table 5. However, if the participants had a serious issue, half would prefer to have a Japanese coach in the future because they felt they could express themselves more clearly in their native language. Nevertheless, there were also positive responses to conducting the session in English, as shown in Table 6. Thornton (2012) states that an intervention in a second language should consider techniques to support the coachees’ language to allow them to express themselves. The participants were recruited based on their TOEIC score, with 600 as a general baseline and 690 and 700 as the participants’ highest scores. The second language proficiency may still be too low for coaching in a second language to feel satisfactory, as noted by Kato and Mynard (2016). However, the session goals were perceived as beneficial, suggesting that the topics of language education were familiar enough for the coachees to benefit from the session.

Table 4

Participants’ Responses to Being Asked, “What difficulties did you have when using English for coaching?”

Table 5

Participants’ Responses to Being Asked, “What are some advantages of coaching in Japanese?”

Table 6

Participants’ Responses to Being Asked, “If you had a serious issue, would you prefer coaching in English or Japanese? and why?”

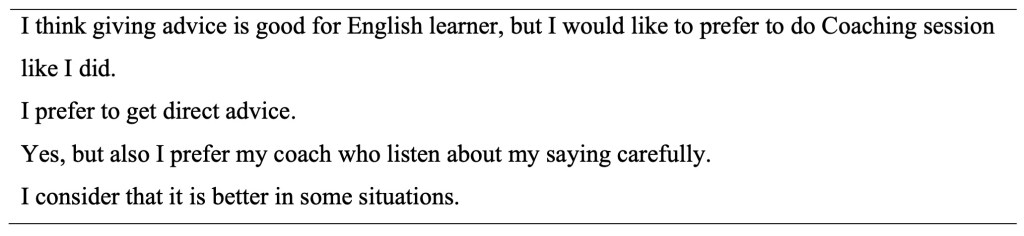

Indirect and Direct Advising Giving

The coach did not give the coachees any direct advice in the sessions; however, Table 7 shows that all participating coachees said they would have preferred direct advice, at least in some situations, which is supported by the results in the literature (Nangalia & Nangalia, 2010; Lam, 2016; Plaister-Ten, 2009). Therefore, offering a flexible blend of skills from coaching, counselling and advising that provides the participant with advice in an indirect manner can be used to satisfy the needs of the coachee (Hobbs & Doffs, 2015; Mozzon-McPherson, 2017; Mynard, 2018; Mynard & Carson, 2012).

Table 7

Participants’ Responses to Being Asked, “Would you prefer if your coach gave your more direct advice?”

Language Teacher as a Coach

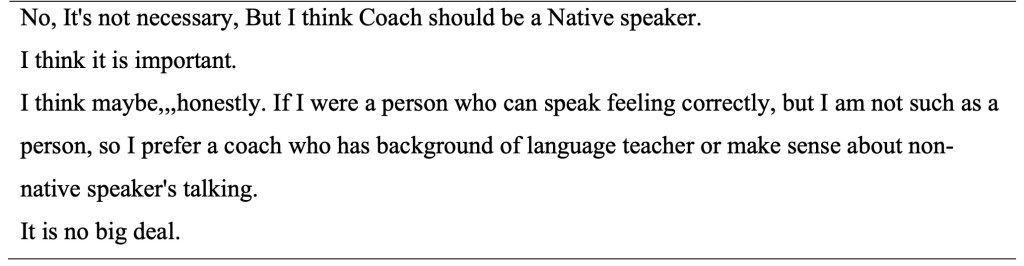

The study investigated the importance of a coach being a language teacher in coaching sessions. Table 8 shows that while two participants did not believe that the coach needed to be a language teacher, they did believe that the coach should speak the same language as the coachee. In contrast, two other participants believed that the coach’s background in language teaching was essential, but only when the coachee was using their second language.

Table 8

Participants’ Responses to Being Asked, “Is it important that the coach is also a language teacher?”

The study’s findings suggest that the use of a second language in coaching sessions can be appropriate in some situations, such as between a language teacher and student, but may not be suitable for other situations, such as when discussing complex or sensitive topics or with lower proficiency. The implications are that coaches who work with non-native speakers may benefit from having a background in language teaching or at least speaking the same language as the coachee.

Conclusion

Some intervention will be needed when there is a culture transition, such as from teacher-directed learning to self-directed learning. Learners may experience difficulties, including low motivation, anxiety, and confusion, when adapting to utilising independent resources such as the SALC. Learners may also be suffering from other issues of which they may be unaware, such as ADHD. These issues can potentially result in limited SALC usage, poor academic achievement or escalate into psychological trauma and bouts of depression. Interventions such as PCC, coaching and LLA can effectively support learners in their transition and have been seen to aid in dealing with psychological disorders in highly functional adults (Griesheimer, 2022). However, these interventions can become ineffective due to misunderstandings and false expectations (Lam, 2016; Nangalia & Nangalia, 2010; Plaister-Ten, 2009).

Using English as a second language for interventions can be successful, even for coachees with lower-level proficiency, provided the topic is not beyond their understanding. Language support, such as metalanguage and scaffolding, is needed for topics which go beyond the capabilities of the second language user. English-speaking coaches, counsellors, and advisors need to be aware that compared to first language sessions, the scope of their interventions is limited by the participants’ language comprehension ability. However, through understanding the intervention structure and when comprehension of the topic is understood, sessions have the potential to be beneficial, regardless of culture.

Notes on the Contributor

Colin Mitchell is a full-time assistant professor and SALC coordinator at Reitaku University. He is studying for his PhD in Transpersonal Psychology at Sofia University, California. His research interests include autonomous language learning, self-directed language learning and SALC.

References

Abbott, G. N., Stening, B. W., Atkins, P. W. B., & Grant, A. M. (2006). Coaching expatriate managers for success: Adding value beyond training and mentoring. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 44(3), 295–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038411106069413

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching autonomy (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Carson, L., & Mynard, J. (2012). Introduction. In J. Mynard & L. Carson, L (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 3–25). Pearson.

Colledge, R. (2002). Mastering counselling theory. Palgrave Macmillan.

Croker, R., & Ashurova, U. (2012). Scaffolding students’ initial self-access language centre experiences. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(3), 237–253. https://doi.org/10.37237/030303

Dam, L. (1995). Learner autonomy. Authentik.

Griesheimer, L. (2022). Academic coaching as a transition model for graduating college students with disabilities. [Doctoral dissertation, Eastern Kentucky University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database.

Hiemstra, R. (2013). Self-directed learning: Why do most instructors still do it wrong? International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 10(1), 23–34.

Hobbs, M., & Dofs, K. (2015). Essential advising to underpin effective language learning and teaching. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 6(1), 13–31. https://doi.org/10.37237/060102

Horai, K., & Wright, E. (2016). Raising awareness: Learning advising as an in-class activity. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(2), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.37237/070208

Rakuten. (n.d.). Executive candidates – Strategy Planning Section, Logistics Business. Retrieved June 9, 2023. https://rakuten.wd1.myworkdayjobs.com/RakutenInc/job/Tokyo-Japan/Executive-candidates—Strategy-Planning-Section–Logistics-Business_1017757-112?_ga=2.173581930.834474608.1686279750-30473663.1686278750&_gl=1*1a6n439*_ga*MzA0NzM2NjMuMTY4NjI3ODc1MA..*_ga_CEVFQGZVJ8*MTY4NjI3ODc0OS4xLjEuMTY4NjI3OTkyMC41Mi4wLjA.

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge.

Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Cambridge Adult Education.

Lam, P. (2016). Chinese culture and coaching in Hong Kong. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 14(1), 57–73. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/informit.829804871962749

Lyons, E., & Coyle, A. (2016). Analysing qualitative data in psychology. Sage.

Nangalia, L., & Nangalia, A. (2010). The coach in Asian society: Impact of social hierarchy on the coaching relationship. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 8(1), 51–66. https://radar.brookes.ac.uk/radar/items/cb7b963c-655d-430a-b13f-b001ed66dbdc/1/

Little, D. (1991). Definitions, issues and problems. Authentik.

Oxford, R. L. (2011). Teaching and researching: Language learning strategies. Longman.

Plaister-Ten, J. (2009). Towards greater cultural understanding in coaching. International Journal of Evidence-Based Coaching and Mentoring, 3, 64–80. https://researchportal.coachfederation.org/Document/Pdf/2083.pdf

Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2017). Reflective dialogues in advising for language learning through a Neuro-Linguistic Programming perspective. In Nicolaides, C., & W. Magno e Silva (Eds.), Innovations and challenges in applied linguistics and learner autonomy (pp. 209–229). Pontes Editores.

Mynard, J. (2018). ‘Still sounds quite a lot to me, but try it and see’: Reflecting on my non-directive advising stance. Relay Journal, 1(1), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010109

Mynard, J., & Carson, L. (2012). (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context. Pearson.

Mynard, J., Kato, S., & Yamamoto, K. (2018). Reflective practice in advising: Introduction to the column. Relay Journal, 1(1), 55-64. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010105

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2018). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Lynch, J. H. (1989). Emotional autonomy versus detachment: Revisiting the vicissitudes of adolescents and young adulthood. Child Development, 60(2), 340–356. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130981

Rogers, J. (2016). Coaching skills: The definitive guide to being a coach (4th ed.). McGraw Hill Education.

Shelton-Strong, S. (2022). Advising in language learning and the support of learners’ basic psychological needs: A self-determination theory perspective. Language Teaching Research, 26(5)963–985. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820912355

Takahashi, K., Mynard, J., Noguchi, J., Sakai, A., Thornton, K., & Yamaguchi, A. (2013). Needs analysis: Investigating students’ self-directed learning needs using multiple data sources. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(3), 208–218. https://doi.org/10.37237/040305

Thornton, K. (2012). Target language or L1: Advisors’ perceptions on the role of language in a learning advisory session. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 65–86). Routledge.

Thornton, K. (2013). A framework for curriculum reform: Re-designing a curriculum for self-directed language learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(2), 142–153. https://doi.org/10.37237/040207

Whitmore, J. (2017). Coaching for performance: The principles and practice of coaching leadership (5th ed.). Nicholas Brealey.