Phoebe Lyon, Kanda University of International Studies

Amber Barr, formerly Kanda University of International Studies

Lyon, P., & Barr, A. (2019). An investigation into the criteria students use when selecting graded readers. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 10(3), 258-281. https://doi.org/10.37237/100304

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

Material selection is one way through which students are empowered to take a more active role in their language learning. With the shifting of responsibility to the students, however, it is important to understand what criteria students are using in the material selection process. This study investigates the criteria students used when making graded reader selections for the extensive reading component of freshman level reading and writing courses at a university in Japan. Data from surveys showed that few students proved able to consistently make selections that met their expectations and that even after multiple book selections, some students continued to struggle with the task. The paper will conclude with suggestions for assisting students to make more informed choices when selecting graded readers.

Keywords: extensive reading, graded readers, self-regulated reading, learner autonomy

In foreign language education, it has become common to encourage students to take initiative and become more active participants in their own learning. Experiential learning involves students learning from their experiences by being actively involved in the process (Kohonen, 2005). In fact, it has been shown that having students take control of their own learning by self-selecting materials is an important educational tool which encourages them to become more aware of themselves as learners and to have more involvement in their own learning (Ellis & Sinclair, 1989). Extensive reading, a course component which is often encouraged within foreign language reading classes, allows students to self-select large volumes of text within their current reading ability (Waring, 2000). However, very little is known about how students undertake such an endeavour. This study was a pilot intended to investigate suitable instruments and methods for researching student graded reader choices. This paper will draw on data to investigate the criteria students used when selecting reading material over time in the hope that this study might guide future research in this area.

Literature Review

In addition to allowing language learners to meet language within natural contexts, which assists in the development of reading fluency and aids vocabulary acquisition, extensive reading has also been shown to increase learner motivation and enjoyment (ERF, 2011). Furthermore, empowering students with the freedom to choose reading materials that are of interest to them at a level they feel comfortable with has been shown to increase reading confidence (Day & Bamford, 2002). In fact, much of the literature that describes the implementation of extended reading into reading courses at Japanese universities have stressed the importance of learners making their own reading selections (Cheetham, Elliot, Harper, & Sato, 2017; Harrold, 2013; O’Loughlin, 2012).

However, it is important to emphasize that in order to see these positive changes in reading fluency and confidence, it is necessary for learners to read at or below their comfort level (Waring, 2000). Accordingly, it can be advantageous for learners to limit selections to reading materials that have been written with language learners of differing levels in mind (Day & Bamford, 2004). Graded readers, therefore, are an appropriate option for language learners because of their attention to grammar and vocabulary, which have been adapted to improve reading comprehensibility (Waring, 2000).

Background

Extensive reading is a component in the freshman level English classes at the private university in Japan where this study was conducted. In the first semester, students in three classes were given reading materials selected by their classroom teachers, who, in this study, were also the researchers. Although going against Day and Bamford’s (2004) purist description of extensive reading, whereby learners choose their own books and thus all learners potentially read different books, this method was decided upon in order to help expose students to a variety of genres and levels as well as to ensure all of them became accustomed to reading in English on a regular basis. However, this procedure may have unduly influenced students later in their independent reading selections, perhaps resulting in students replicating genres previously chosen by their teachers and/or becoming accustomed to reading texts below or above their level. As each new book or text was introduced, a warm-up discussion or activity helped students to recognise and become familiar with different features/elements such as the genre, title, level/difficulty, word count, and when available, abstract of each one.

Prior to students selecting their own graded readers in semester two, students were given an orientation to graded readers, during which important book features were discussed and reinforced. The orientation involved the teacher bringing in books and having students share ideas about what they could gauge about the selection of books. This was done by having students look at the pictures on the cover and possibly inside, reading the titles and blurbs, and checking the assigned levels. Students were reminded how important it was to select books at a level that they felt comfortable with. This was important since Waring (2000) states that students are less likely to become fluent readers if they select texts higher than their current proficiency level. As part of the course, students were required to select a total of five books over the course of 10 weeks, the equivalent of one new book every two weeks. This timeframe is in-line with what Waring (2000) and Nation (2009) suggest exposes students to enough sustained reading and repetition of language.

For this study, students’ reading selections were limited to graded readers. Since editors set parameters for the vocabulary and grammar to which readers are exposed, students at lower levels would be exposed to higher frequency vocabulary and a close range of grammar, and those at higher levels would be exposed to lower frequency words and more complex grammar (Lake & Holster, 2014).

Procedure

Research questions

Giving students autonomy to choose their own graded readers from a vast array of books in a Self Access Learning Center (SALC) or library is an important opportunity. However, even after being exposed to a range of genres and levels of texts and receiving an orientation to graded readers, it can still prove to be an intimidating experience for learners. To learn more about how students make choices and whether reflection can affect future choices, the following questions guided the research.

- What criteria do students use when choosing graded readers?

- How often did students’ choices meet their expectations?

- How did reflective practice influence students’ subsequent book selections?

- Over time, did students make more choices that met their expectations?

Participants

As mentioned, the two researchers were also the teachers collecting data from their classes. Their students were chosen for convenience reasons. As with such research design, it is possible that this affected the type of responses given by students on their questionnaires. Table 1 is a summary of information about the student participants in each teacher’s classes.

Table 1

Teacher and Student Information

Data collection

Students were asked to complete an online questionnaire (See Appendix A) before each graded reader they read, asking why they decided on that particular book. Then, after each reading period, they were asked to fill in a second online questionnaire (Appendix B) to reflect on how the book they selected met their expectations. On this second form, they were also asked to indicate what they would consider when making their next selection. The questionnaires were written in English and Japanese, and students could choose to respond in either language. The rationale was that students might produce more detailed responses than if they were limited to using English. Ten students were also interviewed at the end of the ten-week reading period.

Procedure

As part of their regular classwork, students were required to read a graded reader every two weeks for a period of ten weeks. They were able to choose the graded readers from any source they wished; available resources on campus included the SALC and the university library. Students were asked to complete pre- and post-reading questionnaires for a total of five self-selected graded reader books. The questionnaires were administered over ten weeks during a fifteen-week semester. After selecting each graded reader, students completed reflections prior to reading, to explain what criteria they used to select it. After a two-week period, on the post-reading questionnaire, students reflected on how their expectations were or were not met and what they would consider when choosing their next book. Students had the option to change their choice of book once per cycle, and if they did so, they were asked to explain why they changed books.

Although filling in the questionnaire was part of the regular classroom procedure, only 21 of the total number of 63 students were selected for the final data analysis. The results were limited to these students as it was only these students who completed at least nine out of ten pre- and post- reflection questions for all five of their book selections. It was determined that missing reflections mid-way through the research resulted in not being able to follow the progress of students effectively. In total, there were 207 reflections from the 21 students. Three of these students did not complete the very first questionnaire asking why they chose the first book. The data from the responses to the questionnaires was analysed, and emergent themes were coded by both researchers.

At the end of the semester, once the book selections and questionnaires were completed, interviews were conducted with ten students in order to gain a more in-depth analysis as to how and why students made their book selections over time. Pseudonyms have been used in this paper. A cross-section of participants was chosen to include one student whose book choices always or mostly met her expectations (Haruna), one whose choices only met her expectations once (Aya), two who started to meet their expectations after one or two choices (Kaho and Maki respectively), five who showed a mixed pattern (Takumi, Ami, Hiro, Rina and Honoka), and one who stopped reading one book to choose another (Juri). Participants were informed that they would be given a 1000 yen gift card for their participation in an interview session of no more than 30 minutes. All of the ten students that were approached by the researchers said they would be willing to be interviewed. The interviews were conducted in a semi-structured fashion with both researchers present in the hope of learning more about the students’ general feeling towards reading, how often they read in Japanese and/or English, how they made their book selections, and their final thoughts on what criteria they might consider in the future.

Findings

Of the ten students who were interviewed, eight of them said that they enjoyed reading. Haruna, the student who made five selections that consistently met her expectations, commented that she read about six hours a week for pleasure. Takumi, who was also an avid reader, spent about five hours per week reading. There was only one book, his third selection, that did not meet his expectations. He said it was too difficult, not funny, and that in the end he did not finish it. Later you will read more about how Takumi felt choosing from graded readers limited his choices.

With respect to the two students who indicated that they did not enjoy reading, one of them, Juri, was the student who stopped reading her third book selection to start a new book. She ultimately chose a book that met her expectations, resulting in five of her six choices doing so. Although she said she didn’t like to read in general and that she did not tend to read in Japanese, she did say that she sometimes read in English and preferred reading in English to Japanese.The other student, Aya, said her reading was limited to school assignments; in fact, only one out of the five books she chose met her expectations.

Research Question 1: What criteria do students use when choosing graded readers?

Table 2, below, summarizes the criteria that students used when making book selections. This data was based on the pre-reading questionnaires. If a student indicated more than one reason for choosing a book, each criterion they listed was recorded. Unfortunately, two students did not respond to the first item on the questionnaire for one of the weeks; these are labeled as ‘unclear’.

Selecting a book based on its title or considering the genre were the most common criteria recorded by students. Familiarity with the story/characters was coded separately from having seen the movie/TV show or having had previous experience reading the book; however, all three of these categories tend to fall under a larger category of ‘familiarity with the content’. If combined, the results for ‘familiarity with content’ would be the most common criteria for selecting a book. Nevertheless, these were kept separate as the researchers thought it was important to distinguish between these subtle differences. Reading the blurb, considering the level, and looking at the cover picture were also criteria students quite often used to choose books. Less commonly used criteria were getting recommendations from other students, friends, or learning advisers, looking at the pictures inside a book, having previously read the book in either Japanese or English, and being familiar with the author.

Table 2

List of Criteria, Taken From the Pre-reading Questionnaires Students Used When Choosing Graded Readers

Table 3 lists the codes identified from the post-reading questionnaires in relation to what students said they would consider when choosing their subsequent selection after finishing their current book. In these post-reading reflections, students most often said they would consider the level of the book. In many cases, students indicated that they would choose a book of a higher, lower, or the same level, but eight of the responses just mentioned ‘level’. Considering the genre or content were also quite common responses. Checking the length, blurb, and title were less common, but not insignificant. In some instances, students said they would look at the cover, but it was unclear if that meant they would look at the picture, read the blurb, look at the word count, check the level, or a mixture of or all of the above, so cover was coded separately. It was interesting that one student said they would look to see how many times a book had been previously borrowed, writing that this might indicate that the book was popular, and therefore, a good choice.

Table 3

List of Criteria, Taken From the Post-reading Questionnaires, Students Said They Would Consider When Making Their Next Book Selection

Table 4

List of Criteria, Taken From the Interviews, Students Said They Would Consider When Selecting Graded Readers in the Future

As seen in Table 4, when students were asked in interviews what they would consider in the future, the same trends were found as those in Table 3. Level was the most common response, followed by genre, content, and blurb.

Research Question 2: How often did students’ choices meet their expectations?

In order to determine whether students’ book selections met their expectations, their responses were coded. Table 5 summarizes the codes and indicates the frequency a student’s expectations were met, while Table 6 summarizes the codes and frequency a student’s expectations were not met. Often, students listed more than one reason for how their expectations were or were not met. In these cases, multiple codes were tallied. Furthermore, when students indicated that they were satisfied with the book in one regard (“it was interesting”), but not in another (“it was too difficult”), more than one code was recorded, this time across the two categories.

Table 5

Codes Indicating a Book Met Students’ Expectations

Students often found their selections to be interesting, exciting, good, fun, or funny. Being at a comfortable level was another common response, followed by enjoying the content, enjoying the genre, and learning new information. Enjoying the content and the genre, as well as learning new information, could also indicate that the students found the book to be interesting or exciting; however, if students expressed content, genre or learning information explicitly, these were coded separately as those responses indicated more than just a general feeling. Although not mentioned as often, enjoying the pictures in the book, and finding a book challenging, the content unpredictable, the length appropriate, or the content different to their expectations while still being interesting were also reasons that indicated that a book met the students’ expectations.

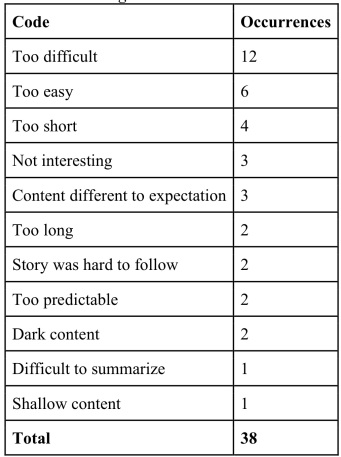

Table 6

Codes Indicating a Book Did Not Meet Students’ Expectations

Stating that a book was too difficult was the most frequent response for why a book selection did not meet students’ expectations. The next most common reason was that their choice had been too easy. Other less recurrent responses were that book choices were too short, not interesting, or that the content did not match the students’ expectations.

It appears that when students self-selected their graded readers, their choices met their expectations 65% of the time (see Table 7). However, there were instances when students indicated that a selection met their expectations in one regard, but not in another. If these books are also included here as having met their expectations, it can be said that students’ expectations were met 69% of the time over the course of the ten-week study. It should be noted that there are 106 responses documented rather than 105, the number that might be expected. This is due to one student deciding not to continue reading the initial choice they made and subsequently choosing a second book in that two-week period. Whilst the first book did not meet this student’s expectations, their second choice did.

Table 7

How Often Students’ Choices Met Their Expectations

Table 8 summarizes whether or not students’ choices met their expectations with respect to their selection criteria. If students listed more than one criteria, each of the criteria that the students listed was recorded. Selecting a graded reader based on familiarity with the author (one instance) resulted in that student’s expectations being met. Making a selection based on the book’s title resulted in an 88% chance of a book meeting students’ expectations (21 out of 24 instances). When selections were made using the criteria of level or looking at the cover picture, expectations were met 11 out of 15 instances (73%). Although genre ranked on par with looking at a book’s title (see Table 2), selecting a book this way only resulted in students having their expectations met 16 out of 24 instances (67%). Whether or not the book had pictures inside did not seem to be a common criteria used when making book selections. Even so, this resulted in two out of three (67%) of the book choices made this way meeting expectations. Recommendations from other students or friends only resulted in those students’ expectations being met two out of four instances (50%), while the one recommendation from a learning advisor led to that student’s expectations not being met. While more selections were made based on familiarity of the story than having already seen the movie or TV show, both resulted in a 64% success rate of meeting the students’ expectations (nine out of 14 and seven out of 11 times respectively). On the other hand, the one instance of a book previously having been read by a student resulted in them not having their expectations met. Familiarity with the author was also only recorded once, but it resulted in the book selection meeting the student’s expectations for that book.

Table 8

How Often Students’ Choices Met Their Expectations Based on the Selection Criteria

Through the interviews, more detailed information about why students made their book choices and how those choices met their expectations was gained. It became apparent that students had not indicated all of the criteria that they had used when selecting a book. For example, in one interview, several students commented that they always read the blurb. Here is an excerpt from Hanrua’s interview.

Haruna: Uh, and I, always I read summary before I choose.

Researcher: Mm-hm. And do you think that helped you make better choices?

Haruna: Ah, yes.

Researcher: Why do you think it was a good idea?

Haruna: Uh, there are many fantasy book, but I have to choose one for, for the week, two weeks.

Researcher: Mm-hm.

Haruna: So to choose excellent one for me, I read summary.

However, in the pre- and post-reading questionnaires, Hanrua had only stated that she had or would read the blurb three times out of her ten responses. Rather, in the questionnaires, she mostly commented that she had or would consider the genre.

It also became apparent that some students chose to read genres in English which they also enjoyed reading in Japanese. Those who chose different genres generally did so with purpose. For example, one student, Kaho, avoided her preferred genre of mystery because she thought it would be too difficult to read in English.

Kaho: If I read mm…mystery books in English, maybe I can’t understand because it is very difficult.

Other students, seemed to vary the genres they chose. For example, Takumi found his choices limited when having to select a graded reader, and this resulted in him having to make selections that may not have been his preferred genre. He said he preferred to read about economics and social issues to expand his knowledge.

Takumi: ..I have to say, uh, there wasn’t, uh, many choice for me. When I, I usually go to library there, um, there was kind of like romance or just too easy one. Many kind of things that, uh, didn’t fit with me, so wh… uhh..I thought it, it could be most interesting for me, so I just chose it.

Over the course of the study, it became apparent that Haruna, who chose multiple genres, made selections that always met her expectations. It became clear in the interview, however, that she read up to six blurbs/summaries before choosing a book. Whilst reading the blurb helped her make choices that met her expectations, two other students who also always read the blurb and consistently chose books from genres that they liked, were less satisfied with their choices after determining that the levels were not appropriate. Takumi, who was also mostly successful in meeting his expectations, also took time to read the blurb, at least partially, before making a selection.

Whilst Maki indicated that her preferred genre was romance, she tended to make choices based on movies she had seen, even if the books were not of that genre. Although she chose familiar titles, her expectations were not met twice due to the level being either too easy or too difficult. Ami, who also chose books based on movies, and who liked to read short stories and books based on movies in Japanese, also struggled to find books that were appropriate to her level.

Both Rina and Honoka tended to choose books from their preferred genres. Although they were not always successful at choosing books that met their expectations, Rina made choices that she felt met her expectations four out of five times, whilst Honoka had her expectations met three times and had mixed feelings for her final two selections.

Finally, Hiro said he wanted to choose the same genre to read in English as he liked in Japanese. He stated that he liked historical novels or biographies, but it became obvious in the interview that unbeknownst to him, he had chosen a fictional romance story, and that in fact, most of his selections did not fit his preferred genre. The results were mixed when it came to him having his expectations met.

Research Question 3: How did reflective practice influence students’ subsequent book selections?

It was difficult to draw any conclusions from the data as to whether reflective practice influenced students’ decision making when they made subsequent book choices. For example, one student, after finding a book was too easy and did not match their level, wrote in the post-reading questionnaire that they would look at the length and consider the genre for their next selection. Whilst the length of graded readers might help indicate the level, neither of these considerations (length or genre) tend to lend themselves to choosing a book that might better suit the student’s level. On the other hand, another student said that after finding a book too easy, they would choose a book of a higher level next time. However, as can be seen from Tables 2, 3, and 4, what students said they would do did not always correlate with what they then said they did. As mentioned above in the section summarizing the results for selection criteria, it became apparent that students were making their selections based on more than what they had indicated on the questionnaires. Therefore, it was not possible to determine whether students had considered what they had written on their reflections (on the post-reading questionnaires) when selecting subsequent books if they had not also explicitly written the same criteria on their post-selection (pre-reading) responses.

Research Question 4: Over time, did students make choices that better met their expectations?

Table 9

How Well Students Met Their Expectations Over Time

Table 9 indicates that students’ expectations were met more often than not for books two and three. However, the number of books that met students’ expectations dropped for books four and five. Conversely, after initially dropping, the number of selections that did not meet students’ expectations increased for book four and then quite noticeably for the fifth book. Of the ten responses for book five, five students stated that their choice was too difficult, another that their choice was too short, one said that their book was too gory, one too predictable (they had wanted something thrilling), and the last one said that it was not thrilling (they had wanted a mystery).

Discussion

While the 69% may not seem particularly high for the number of times students’ expectations were met by their book choices in this study, a study by Harold (2013) indicated that students tended to enjoy books that they self-selected more than books that they had been assigned previously by their classroom teachers. This was perhaps validated in this study with the finding that the most common criteria coded for a book having met their expectations were selections had been found interesting, exciting, good, fun, or funny. Finding the books to be of a comfortable level was also a common reason for meeting expectations.

However, common responses were also that students’ book choices were either too difficult or too easy. This indicates that finding books that matched their reading level was a struggle. Interestingly, when selections were made based on the level, expectations were met 73% of the time, indicating that this is a good strategy when employed. Of the most common criteria coded after selection of a book (title, topic, and blurb), none of these would appear to be indicative of the level. Although reading a blurb might give some indication of level if it were written at the same level of the text contained inside the book, the title does not seem to be very useful at all.

Other commonly coded criteria were familiarity with the story/characters and having previously seen the movie or TV show. A strategy implemented by one student was to check how many times a book had been borrowed. The assumption was that this made a book popular. These criteria used by students to select books may have been due to feeling overwhelmed with a large selection of books in the SALC and library. However, this led to students’ expectations not being met, mostly due to the books being of an inappropriate level.

Interestingly, before making subsequent book choices, level was the criterion most often cited by students, and this was also the most common response in the interviews when students shared what they would think about in the future. This item indicates that students were often dissatisfied with the level of their previous choices. So, why was this mentioned less often when students commented on how they made a book selection? Was this due to them simply not noting it, or did they neglect to consider level when confronted with the task? As was highlighted by the interviews, it may have been the former since it became clear that the students who were interviewed had neglected to write in each reflection all of the criteria that they had used.

Although there is a possibility that having text selections made for students in the first semester of the course may have influenced their future selections, it is still a part of the procedure recommended by the researchers since the results of the study appear to reinforce the need for students to have an exposure to a variety of genres and elements of texts. However, in the second semester, more emphasis could have been placed on having students critique the level and its appropriateness for them since this was often a challenge for many of them. Although graded readers show a level on them, these levels vary by publisher and are not always comparable, so if students are changing between publishers, it can lead to students not being able to adjust their level effectively. Lake and Holster (2014) found that there was a considerable overlap in the variation in difficulty across levels for some publishers, concluding that students must take care when making a selection befitting their reading level.

The interviews also highlighted that some students were aware that certain genres might be more challenging than others. Therefore, basing a choice on the genre may have been useful in helping some students make level appropriate choices. In fact, when books were selected based on the genre, students’ expectations were met two thirds of the times. Even if the chosen genre was not students’ preferred ones, being aware of genres they liked appeared to be important.

Another interesting finding was books chosen by students were too short since the length should be something that could be readily gauged by the number of pages and/or word count listed on the back of the book. Furthermore, Cambridge, Scholastic, Penguin, and Pearson all provide word counts on the back of graded readers. Oxford is the only publisher that appears not to. This indicates that students were perhaps not taking the time to check this information. Finally, recommendations did not seem to prove good choices to meet expectations. This was not surprising since others are not necessarily able to fully understand someone’s interests or appropriate level.

With so many students indicating that their book selections did not meet their expectations, it was surprising that only one of the students took advantage of stopping reading one book to start another. With only two weeks to read, it was possible that students felt that they didn’t have enough time to start and finish a book if they had left it too late. In hindsight, this would have been a good question to have included in the interviews.

Limitations

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was not piloted prior to conducting this study. After reviewing the questionnaire responses and conducting follow-up interviews, problems arose regarding the analysis of the data. The inclusion of a likert scale showing how well books met students’ expectations might be a useful addition to more accurately gauge any changes over time. The interviews highlighted further limitations, specifically related to the post-reading questionnaires. Whilst students indicated what they would consider when choosing the next book, interpreting some of the data proved problematic. For example, when students indicated they would ‘look at the cover’, it was not clear whether they meant they would look at the picture, read the blurb, look at the word count, check the level, perform a mixture of, or all of the above.

The interviews also highlighted another limitation. For example, it became clear that a full breakdown of all of the criteria that students had used when making book selections had not been included in the responses on the questionnaires. For example, some of the students reported that they had read the blurb more often than they had previously noted on the questionnaires. Therefore, now, having an awareness of the most common strategies used by students, in a future study it could be useful to have a list of possible criteria from which students could choose all of the criteria they used/would use to provide a more accurate representation.

It also became apparent from the interviews that students were not always fully aware of the genre they had chosen. Thus, it might have been beneficial to have them state what they believed the genre was if this option was listed as their selection criterion. That way, teachers/researchers would know if genre awareness needed to be reviewed.

Finally, there was a limited connection between the question in the post-reading questionnaire that asked students to consider how they might select their next book and the subsequent pre-reading questionnaire. For example, when a student stated that they would consider the level on the post-reading questionnaire, but then wrote that they chose the next book by looking at the title, it was unclear if they ignored their advice or looked at the title instead of or in addition to checking the level. Having the questionnaire as a booklet package (rather than as a digital form) would have allowed students to go back and review their past choices and reflections. Students could have been asked to check off which of the criteria they had used having made their subsequent selections, which in turn might have also encouraged more explicit reflective practice. Therefore, in a future study, it might also be useful to have students list the criteria in the order they considered them and/or indicate the importance they allocated to each one.

Students

As with any research, factors related to individual student differences linked to reading experience, students’ proficiency levels, and also their willingness to participate may affect the results. Furthermore, it is possible that students taking the classes in different departments and/or with different teachers may have affected the results.

Although students were given the opportunity to complete the questionnaires in either Japanese or English, the responses still appeared to lack a high level of detail. This highlights the importance of training students to write suitable reflections.

Research procedure

Even though three classes participated in the study, with a total of 63 students, the criterion set by the researchers for including the data in the study was limited to using almost complete data sets for any student. As a result, only data from 21 student participants was included. Having a larger data set would have potentially demonstrated more defined trends. Also, due to the subjective nature of interpreting qualitative research data, care was taken when interpreting the results; however, determining when to conflate codes and when to keep them separate was not always easily discernible.

The length of the study was another limitation. Having a longer period of time for students to choose books, reflect on their choices, and choose subsequent books may have led to being able to see more trends evolve. Furthermore, although the interviews allowed for a follow up with a section of the students, due to the small number of students in the study, interviews with all 21 participants may have once again resulted in clearer trends becoming apparent.

Also, whilst the interviews were semi-structured, it was clear that more information could have been gleaned from them, so perhaps more structure would have been helpful. Trialling of the interview questions by the researchers beforehand would have been beneficial to become more familiar with the research questions, to practice their interviewing skills, and to identify problematic questions or additional questions that might have been useful.

Finally, it might have also been more informative if all students had been asked to reflect on how the post-reading reflections had influenced their reading choices/whether doing reflections had been useful.

Conclusion

Although it can be valuable to encourage students to make their own choices when it comes to material selection, the data from this study showed that after reflecting on their previous four choices, many students were still not able to make a final selection that met their expectations. It appears that informing students of types of criteria and reinforcing criteria that tend to work more often, as well as highlighting ones that do not, is an important part of orienting students to graded readers and how to more successfully select a book to meet their expectations.

Furthermore, even though recommendations and familiarity with a story makes the search for books easier, once identifying a possible selection, it would be prudent for students to do some additional research. Even checking the publishers level does not seem to be enough. Reading the blurb could be useful, but even more useful might be to read a few pages to really gain an understanding of the grammar and vocabulary levels. It might also be in students’ interests to keep reflecting as part of their experiential learning cycle. This could be where they keep a diary to record the books they are reading, especially with respect to the levels (being sure to document the publisher) and the genre, and then to describe how well each selection met their expectations.

It is clear that many learners need ongoing guidance on the path to becoming autonomous learners. Reflection is a common activity promoted by learning advisors in SALCs that can assist learners on this journey. However, it could also be advisable for classroom teachers to consider incorporating reflective practice (Kolb, 1984) into coursework activities, which necessitates students to undergo a concrete experience, reflect on the experience, learn something from it, and then make a plan based on what they have learned. With respect to graded reader selection, students might benefit from actively reflecting on the resources they are choosing and the methods they are using to choose them. SALCs could help support learners and teachers by offering assistance with the design and implementation of self-reflection activities that have been created for material selection, and in this case, graded readers specifically.

Finally, other recommendations were mentioned in a previous paper by the researchers (see Barr & Lyon, 2017), such as clearly signposting important factors related to selecting graded readers in SALCs and libraries, reminding learners to ask SALC staff for advice, and having a readily available guide/checklist to be used by students when making book selections. It is hoped that these recommendations might be of support for anyone assisting students in the self-selection of extensive reading material in the future.

Notes on the Contributors

Phoebe Lyon is a Principal Lecturer for Curriculum and Assessment at Kanda University of International Studies, Japan. Her research interests include learner autonomy, learner identity, materials development and assessment.

Amber Barr was formerly a Senior Lecturer at Kanda University of International Studies, Japan. Her main research interests are extensive reading and learner autonomy.

References

Barr, A., & Lyon, P. (2017). How to support students in selecting graded readers. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(3), 247-254. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep2017/barr_lyon

Cheetham, C., Elliot, M., Harper, A., & Sato, M. (2017). Accessibility and the promotion of autonomous EFL reading. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(1), 4-22. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/mar17/cheetham_et_at

Day, R., & Bamford, J. (2002). Top ten principles for teaching extensive reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14(2), 136-141. Retrieved from http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/rfl/October2002/day/day.html

Day, R., & Bamford, J. (Eds.) (2004). Extensive reading activities for teaching language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, G., & Sinclair, B. (1989). Learning how to learn English: A course in learner training. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

ERF (2011). The Extensive Reading Foundation’s guide to extensive reading. Retrieved from http://www.erfoundation.org

Harrold, P. (2013). The design and implementation of an extensive reading thread in an undergraduate foundational literacies course. The 2nd World Conference in Extensive Reading Conference proceedings. Seoul: Extensive Reading Foundation. Retrieved from http://keera.or.kr/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/ERWC2-Proceedingsnew.pdf#page=230

Kohonen, V. (2005). Learning to Learn through Reflection – An Experiential Learning Perspective. Retrieved from http://archive.ecml.at/mtp2/ELP_TT/ELP_TT_CDROM/DM_layout/00_10/05/Supplementary%20text%20E.pdf

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lake, J., & Holster, T. (2014). Developing autonomous self-regulated readers in an extensive reading program. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(4), 394-403. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/dec14/lake_holster/

Nation, P. (2009). Teaching ESL/EFL reading and writing. New York, NY: Routledge.

O’Loughlin, R. (2012). Integrating learner autonomy into the design of a reading curriculum. In M. Hobbs & K. Dofs (Eds.), ILAC Selections: 5th Independent Learning Association Conference 2012. Christchurch: Independent Learning Association, 2013.

Waring, R. (2000). The ‘why’ and ‘how’ of using graded readers. Tokyo, Japan: Oxford University Press.

Appendices

Appendix A

Pre-reading Reflection Question

Why did you choose the book? Explain.

Q1, なぜその本を選んだのですか?理由を説明しなさい

Appendix B

Post-reading Reflection Question

- In which ways did this book meet or not meet your expectations? Explain.

Q1. どんな意味でこの本はあなたの期待に応え(あるいは期待を裏切り)ましたか?説明しなさい。

- Did you start a book that you didn’t finish? If yes, why didn’t you finish that book?

Q2, 本を最後まで読み終えずに終わりましたか?もしそうならば、その理由はなんですか?

- What will you consider when choosing the next book?

Q3, 次の本を選ぶ際には、どこに着目しますか?