Maria Giovanna Tassinari, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany

Tassinari, M. G. (2018). Autonomy and reflection on practice in a self-access language centre: Comparing the manager and the student assistant perspectives. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 9(3), 387-412. https://doi.org/10.37237/090309

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

The present paper illustrates some structures and processes established in order to make the Centre for Independent Language Learning, a self-access language centre (SALC) at the Freie Universität Berlin, an autonomous and autonomy fostering learning and working environment. Since the SALC staff is mainly composed of student assistants, one of the aims of the SALC manager is to foster the student assistants’ autonomy and their reflection on practice by giving them spaces for decision-making and personal initiative, supporting them in keeping track of their work, asking critical questions, planning, implementing and evaluating their projects and thus helping them to develop as professionals while actively contributing to a reflective practice at the SALC.

As a part of the reflection on practice process, a survey among the student assistants was conducted, to gather data about the student assistants’ perspective on their experience at the SALC, their perception of autonomy, their overall evaluation of their work as well as comments and suggestions for further development of the SALC. While reflecting on ways to manage the SALC at the Freie Universität Berlin, the present paper intends also to contribute to the more general discussion on how to evaluate the impact of self-access language centres.

Keywords: self-access language centre, reflective practice, autonomy, evaluation of self-access language centres

In the present article, I will reflect on my experience as a manager of the Centre for Independent Language Learning, a self-access language centre (SALC) at the Language Centre of the Freie Universität Berlin. The SALC offers language learning resources and support for the development of autonomy in more than thirteen languages. Its only staff is composed, beside the manager and a librarian, of thirteen student assistants, regularly employed by the university with a two-year part-time contract. Since the development of learner autonomy is one of the SALC aims, it is important that student assistants, beside some theoretical notion about language learning and learner autonomy, also experience themselves, as learners or as staff members of the SALC, some autonomy, in order to be able to support other learners and contribute to making the SALC a (more) autonomy-fostering environment. For this reason, as the SALC manager, I aim to develop the student assistants’ awareness for their own autonomy by fostering critical reflection.

By doing this, I am ideally in line with a pedagogy for autonomy in language education (among others, Dam, 1995; Little, Dam & Legenhausen, 2017) and approaches which involve learners as researchers (among others, Allwright & Hanks, 2009; Van de Poel, 2018), and advocate for giving them more responsibility to actively pursue meaningful questions (Hanks, 2015). Rooted in the tradition of critical pedagogy, experiential and inquiry-based learning (Dewey, 1963; Freire, 1973; Kolb, 1994; Kohonen, 2001), these approaches value individuals’ reflection in and on practice (Schön, 1983).

The present paper aims to illustrate how a pedagogy for autonomy and reflection-in and on-action is implemented with student assistants at the SALC at the Freie Universität Berlin. In addition, it aims to reflect upon this experience, in order both to improve the practice itself and to see how the experience at the SALC impact the student assistants’ development as future teachers or professionals in the field of language learning and beyond.

The research question underlying this study is: How does their work at the SALC contribute to fostering the student assistants’ autonomy and capacity for reflection?

This research question is investigated through observation and reflection on experience, using field notes, personal reflections, and a questionnaire on the student assistants’ perception on their activity and personal development during their service at the SALC. This paper will focus on the results of the questionnaire as a basis for evaluating the reflection processes in place at the SALC.

By answering this question and reflecting on this experience, I hope to contribute, at least partially, to the complex question of how to evaluate SALC provisions by taking into account the perspective of the SALC student staff (see Morrison, 2008).

I will start this contribution by briefly defining the notions of autonomy, reflection, reflective practice, and research. I will then illustrate what the SALC offers, how its work is organized and how the student assistants are involved in the development and reflection processes; I will also report on some of the projects realized by them. I will also present and discuss the results of the survey among the student assistants on their personal evaluation of their work and their autonomy at the SALC. A final reflection on conclusions to be drawn from the results will close this contribution.

Reflection, Reflective practice, and Research

Although the term is part of our everyday vocabulary, I would like to start by defining ‘reflection’. According to Boud, Keogh and Walker, reflection is “an important human activity in which people recapture their experience, think about it, mull it over and evaluate it. It is this working with experience that is important in learning.” (1985, p. 19). As a SALC manager and language teacher, I asked myself how to involve the student assistants at the SALC in this process of “working with experience”, critical inquiry and evaluation of their experience in order to help them make decisions for themselves, to further develop as professionals and also to ensure quality within the SALC provision. And as a researcher, I wondered how this reflection could be linked to research in an academic environment. Nonetheless, while I was supporting my own work as a SALC through my PhD research on learner autonomy (2004-2009), I was aware that I could not expect from the student assistants to engage in research to the same extent as I was doing.

Looking at this development retrospectively, I would say that some seeds of critical pedagogy planted in the early years of my professional life as a teacher (some in-service training and frequent discussions with a good friend of mine who had been majoring in the field of education), had been brought to life through the encounter with a pedagogy for autonomy. Understanding autonomy as a capacity for “detachment, critical reflection, decision-making, and independent action” (Little, 1991, p. 4), and self-evaluation as “the hinge on which autonomy turns” (Little, Dam & Legenhausen, 2017, p. 95), helped me to recognize the importance of self-monitoring and critical reflection upon one’s own work.

Then, while looking for an approach compatible with the institutional constraints (among others, the student assistants’ workload within and outside the SALC), I discovered Schön’s ‘reflective practitioner’ and the notions of ‘reflection-in-action’ and ‘reflection-on-action’. According to Schön, the reflective practitioner

allows himself to experience surprise, puzzlement, or confusion in a situation which he finds uncertain or unique. He reflects on the phenomena before him, and on the prior understandings which have been implicit in his behaviour. He carries out an experiment which serves to generate both a new understanding of the phenomena and the change in the situation.

When someone reflects in action, he becomes a researcher in the practice context. He is not dependent on the categories of established theory and technique, but constructs a new theory of the unique case. (Schön, 1983, p. 68 stress added).

Reflection-in-action means therefore constructing an understanding of a given situation, formulating a puzzle, a question (for example a problem to be solved), experimenting, reframing one’s understanding of the situation, and changing the situation in the course of action. Reflection-on-action occurs afterwards, problematising the action after it has been concluded.

This approach is similar to the action research approach, as Schön himself points out, referring to Kurt Lewin as a precursor of the “idea of an action science” (1983, p. 319), since action research is conducted by the actors themselves with the aim of understanding and improving their actions (see, among others, Reason & Bradbury, 2013; Van de Poel, 2018). In the context of the SALC, this reflective practice is collaborative, since it is conducted with and by persons within the SALC, and, to some extent, participatory, since it is done “with, for and by persons and communities, ideally involving all stakeholders both in the questioning and sensemaking that informs the research, and in the action which is its focus” (Reason & Bradbury, 2013, p. 2).

To sum up, the reflection at /on the SALC entails the research conducted by the author, some research initiated and conducted by students (for example students majoring in language teaching, Estrada, 2012; Lopez, 2013; Hujová, 2014), and some reflective practice conducted together with the student assistants, which will be illustrated in the following.

The SALC at the Freie Universität Berlin

The SALC is part of the Language Centre and a self-access learning space offering resources and learning support for about 20 foreign languages. It is based on the following pillars:

- a variety of materials and resources in print form, as well as DVDs, audio resources and software;

- support for autonomous language learning: study guides, workshops, and a language advising service;

- a website (http://www.sprachenzentrum.fu-berlin.de/slz/index.html) with a language learning specific catalogue, guidelines for autonomous learning, and a vast collection of links for language learning;

- a tandem programme for language partnerships;

- support for social learning in form of tutorials, game nights and space for self-organised learning groups.

The SALC staff is composed of the manager, a librarian and thirteen student assistants. The student assistants work with a two-year contract, which, in some cases, they can renew for another two years, for an amount of 10 hours per week. Besides their student status they are therefore regular employees of the university with paid holidays and leave.

Interns may join the staff for a term. In addition, a small task force constituted by three lecturers support the self-access manager in reflecting on the SALC provision, designing teacher training and / or suggesting further developments. For the purpose of the present paper, I will focus on the work with the student assistants and on the survey conducted among them.

Work at the SALC

The SALC is open every day to learners and teachers. Besides the opportunity to learn on site with the resources provided, the SALC offers assistance in finding appropriate materials, guided tours for classes with their teachers, language learning advising, tutorials and workshops.

The manager coordinates the pedagogical provision, trains and supports the student assistants, provides language advising and organizes workshops for student and teacher development. The librarian is in charge of processing the resources acquired, of ensuring the SALC schedule and opening hours, of supporting the student assistants if they have questions concerning the materials. The student assistants have manifold tasks: they welcome learners, help them to find materials, describe learning resources for the online catalogue, maintain and further develop the website with a huge collection of links for language learning, run the tandem programme, communicate with teachers, in some case make peer advising, design game nights and peer workshops. They work in pairs in shifts, which are negotiated among the student assistants themselves one week before the term begins and are then maintained for the whole semester, to guarantee the SALC opening hours. Each student assistant works twice a week for a five- or six-hour shift. The SALC manager and the librarian are also on site to support the student assistants in their work.

The tasks of the student assistants have been evolving in the course of the years, depending on the development of the SALC provision. Before the SALC was established, the facility was a ‘Mediothek’, whose only provision consisted of computers and a grammar cupboard for German as a foreign language. The student assistants’ task was to oversee learners and help them by question on how to use the computer software.

Once the SALC was established (2005), learning materials were then acquired, processed and described in a catalogue, a website was set up; the tandem programme, which was first run by a German lecturer, was taken over by the SALC and extended to all languages (2006), a language advising service and workshops were established. Along with the development of the pedagogical provision, the student assistants’ work had to be reorganized: staff meetings, pedagogical workshops and guidelines were set in place, always in cooperation with the student assistants themselves. Besides routine everyday tasks such as welcoming learners at the SALC and providing information about the resources, teams were established according to the student assistants’ competences and interests to work on particular areas: a website team, a tandem team, and teams for particular projects. To manage the everyday tasks and the projects, communication plays a central role: to keep track of the work and to ensure asynchronous communication, logs were established so that for example a task initiated by a student assistant could be taken over by another one of the team during the following shift.

Although these structures may be perceived as constraining and time consuming, they are necessary to ensure common workflows and shared criteria, for example for giving information, for matching tandem partners, for describing learning resources for the catalogue, etc. I am aware that this may reduce the student assistants’ autonomy, which is an issue I will reflect on in the discussion of the survey results.

Practice and research at the Language Centre

To illustrate the institutional constraints at the Language Centre and at the SALC, it is worth stressing that language centres in Germany are peculiar institutions within the university, since their specification entails teaching, but mostly not researching. The Language Centre at the Freie Universität Berlin has neither funding for research nor time allocated for it. This may be one of the reasons why research is done, if at all, only on a voluntary basis. However, part of the faculty and of the management of Language Centres in Germany insist on the necessity of integrating research in order to improve language course provision and/or to ensure quality: for example the AKS Conference, the conference of the Language Centres in German speaking countries, 2016, was devoted to the unit of teaching and researching in language education in higher education, “Wilhelm, Alexander und wir: Einheit von Lehre und Forschung in der Fremdsprachenausbildung an Hochschulen” (https://aks2016.hu-berlin.de/); at the Bremer Symposion, held every two years, workshops on research on language learning and teaching are offered (see https://www.fremdsprachenzentrum-bremen.de/2091.0.html).

Involving the Student Assistants in the Development and Reflection Process at the SALC

Student assistants at the SALC are selected preferably among philology students or student teachers, and, in general, they speak more than one language (some up to four or five); some of them are German, some others come to live and study in Berlin from other countries. The student assistants’ team is therefore highly diverse; each of them has particular competences and interests, and on this basis, they are invited to contribute to further develop the SALC provision. Due to their double status of students and of staff members, they sometimes bring stimulating perspectives into the SALC.

In order to be fully involved in the SALC, they undergo an initial and an in-service training. This includes first an introduction to the SALC, its pedagogical framework, the resources and the student assistants’ role within the SALC; then pedagogical workshops on topics such as improving communication with users, describing learning materials in the online catalogue, defining criteria for online resources, contributing to the SALC wiki, peer-advising for language learning. The topics of the pedagogical workshops are negotiated according to the student assistants’ needs and/or priorities in the SALC development.

As the manager of the SALC, I see as my task to negotiate with each of the student assistants which tasks or projects they will undertake, besides ensuring the everyday routine. Some of them are willing to initiate new projects, which we choose according to their competencies, their area of interest, and their priorities for their personal and professional development. It is essential to me to give them, similarly to the learners which come to the SALC, room for choice and experimentation within the SALC framework; I offer my support and guidance for implementing the project; finally, I reflect on and evaluate with them the outcomes and the process itself. Each project undergoes the following phases:

- identifying needs, for example learners’ needs;

- planning action to cater for these needs;

- piloting the new provision;

- evaluating the pilot phase;

- if necessary adapting the provision.

These phases are implemented recursively, according to the LANQUA quality model, which was developed in a project funded by the Commission of the European Communities Lifelong Learning Erasmus Network programme (2007-2010) by a network of teachers and specialist to guide practice, and reflection on practice, and enhance the quality of teaching and learning of languages (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The LANQUA quality model (www.lanqua.eu).

Following this model, several projects have already been implemented and reflected on at the SALC, such as

- redesigning the tandem meeting (a meeting at the beginning of each semester for all students interested in finding a language partner);

- conducting a survey among the participants in the tandem programme to collect a feedback from them and gather data about how they work together, the resources they use, and their needs / their suggestions for improvement;

- planning game nights for tandem partners;

- developing a new concept for the initial training of the new student assistants;

- developing new study guides (for example “Learning languages with songs”);

- designing workshops of German as a foreign language for refugees interested in studying at the university;

- designing workshops on autonomous learning.

Even if some of the projects can be carried out only for few terms (due to external constraints, or because one of the student assistants in charge is leaving), all of them contribute to broadening the educational provision and to further developing the SALC.

In addition, student assistants may also be involved in writing a paper (Friesen, Tassinari & Ulmer, 2010 on the tandem programme) or in a research project: for example, in the research on emotions and feelings in the advising discourse (Tassinari & Ciekanski, 2013; Tassinari, 2016), four student assistants were involved in transcribing advising sessions and identifying expression of emotions and feelings in these.

To sum up, both formal and informal procedures for reflection are encouraged at SALC: informal reflection takes place in individual and group discussions, both on the everyday routine and on specific projects, in staff meetings and in pedagogical workshops; more formal reflection procedures are surveys on aspects of the SALC provision, and the implementation of the LANQUA Quality Model for planning, implementing and evaluating projects.

The Student Assistants’ Perspective

As a part of my own reflection on the SALC, I was interested in investigating the student assistants’ perceptions of their work at the SALC and its impact on their personal and professional development. In particular, I was interested in knowing if and how working at the SALC encourages their autonomy, sense of agency, and critical reflection. My assumption is that if the student assistants do experience autonomy, they are more likely to encourage and support this attitude in learners who come to the SALC.

Therefore, my research question was: How does the student assistants’ work at the SALC, as it is conceived, contribute to fostering their autonomy and capacity for reflection?

Although I collect the student assistants’ feedback on a regular basis by means of individual interviews during and at the end of their service at the SALC, and I am occasionally in contact with some of the former student assistants who come back to the SALC as language teachers with their class, I wanted to gather data from actual and former student assistants more systematically. I thus designed a brief online questionnaire (see Appendix 1). In this questionnaire, after asking some questions about student assistants’ personal data, such as age, gender and duration of their service at the SALC, I asked them how they perceived the atmosphere at the SALC, what they learned through their work at the SALC, and how autonomous they felt in managing the various tasks they accomplished. Some of the questions were multiple choice questions (for example, question No. 4), others were open questions (for example, questions No. 7, 8 and 9), to give the participants the possibility of answering more individually and thus gain better insight into their perceptions. While the answers to the multiple-choice questions were analysed quantitatively, the answers to the open questions were analysed through content analysis (grounded theory). The questionnaire was sent per email to 46 student assistants who had been employed at the SALC from 2007 until 2017. The language of the questionnaire was German, as were the answers by the participants. For the purpose of this paper, questionnaire and answers were translated into English.

Results and Discussion

The questionnaire was answered by 27 student assistants. They identified themselves as 20 females and five males; two of them did not specify their gender (see Figure 2). At the time of the survey (June 2017), four of them were between 20 and 25 years old, ten between 25 and 30, another ten between 30 and 35, and three of them over 35 (see Figure 3). They had worked at the SALC for different amounts of time: one year (six persons), two years (nine persons), three years (five persons), four years (three persons) or more than four years (three persons). One of them did not remember (see Figure 4).

Figure 2. Gender of the participants

Figure 3. Age of the participants.

Figure 3. Age of the participants.

Figure 4. Duration of the student assistants’ service at the SALC.

Figure 4. Duration of the student assistants’ service at the SALC.

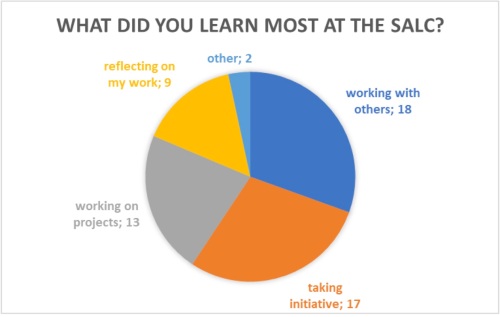

The student assistants’ experience at the SALC

Asked about what they had learned during their experience at the SALC (question No. 4), most of the student assistants participating in the survey stated that they had learned to work together with others (18 answers, 66,6%) and to take initiative (17, 62,9%); they also had learned to work on projects (13, 48,1%) and to reflect on their work (nine, 33,3%) (more answers were possible) (see Figure 5). Additional examples of what they had learned while working at the SALC where given by twelve participants in their answers to question No. 5. These answers can be attributed to the following categories: working on the tandem programme (three answers), designing German workshops for refugees (two answers), taking responsibility for communicating with colleagues (one answer), for managing the manifold tasks (one answer), working in team to further develop the SALC provision (one answer), taking initiative in supporting individually SALC users (one answer), being friendly and patient in communicating with users (one answer), redesigning and updating the website (one answer), and participating and collaborating to the staff training (one answer). While team work and taking initiative seem to be the most frequent outcomes of their work, the answers differ depending on the student assistants’ individual experiences and the projects undertaken by each of them. Reflection, however, seems to be for many of them a less important outcome.

Figure 5. The student assistants’ learning experience at the SALC.

Figure 5. The student assistants’ learning experience at the SALC.

The student assistants’ perception of autonomy

When asked about how autonomous they felt at the SALC (question No. 6), most of the student assistants stated that they felt autonomous (17, 63%) or very autonomous (four, 15%) while three felt less autonomous (11%) and three not autonomous at all (11%) (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. The student assistants’ perception of autonomy

The reasons provided (question No. 6b) show that their perceptions varied, in some cases diverged, and highlight both factors conducive to autonomy and factors hindering it. Among the twenty-five answers, fifteen brought up positive arguments, four negative arguments, and six mixed arguments (see Tables 1, 2, and 3). As factors conducive to autonomy were mentioned, among others, having the possibility of making one’s own decisions (seven answers), bringing up one’s ideas and finding support for implementing these (two answers), experiencing freedom in organizing and managing tasks (one answer), developing projects also in cooperation with other institutions at the university (one answer). As factors hindering autonomy were identified the working schedule (one answer), the already defined workflows and/or tasks (two answers), and the fact that personal initiative was perceived as not always welcomed (two answers). The mixed answers outlined the contrast between the daily routine, in which one felt less autonomous, and the freedom in taking initiative, and carrying out new projects (one answer); however, the other way around was also mentioned, by a student assistant who felt autonomous in the daily routine, and less autonomous in the long-term projects which had to be negotiated with the manager (one answer). The need to communicate and negotiate with the colleagues was also one of the factors which, in some student assistants’ perception, limited their autonomy (three answers).

Table 1. Reasons for Feeling Autonomous at The SALC

Table 2. Reasons for Feeling Less Autonomous at The SALC

Table 3. Mixed Reasons for Feeling Autonomous at The SALC

A correlation between the student assistants’ perceptions of autonomy and the duration of their employment at the SALC shows that student assistants who worked one or two years at the SALC overall perceived themselves as autonomous or very autonomous (only one out of fifteen perceived themselves as not autonomous at all). The perceptions of the students who worked three or four years at the SALC varies: only three of them perceived themselves as autonomous or very autonomous, whereas five felt less autonomous or not autonomous at all. This changes again for the three student assistants who were employed for more than four years: all of them felt autonomous or very autonomous (see Table 4). A possible explanation of this correlation is that at the beginning of their time at the SALC student assistants perceive -and appreciate- the opportunity they are given to bring on their own ideas into the SALC (even if not all of them could be implemented, see answer No. 5 “I felt our ideas were listened to, but of course not all could be implemented.”). For those who have acquired more experience within the SALC, the opportunity to suggest and implement innovations can increase in the last years of their service. However, the answers of students who worked three years show that some of them felt a lack of trust (answer No.7, “Somehow I felt no trust.”) or of space for decision-making and agency due to the daily routine and the fact that projects had to be discussed with the manager (answer No. 6, “In the everyday routine rather less autonomous (printing, paying attention to students), occasionally more autonomous and very autonomous in projects (homepage).”).

Table 4. Correlation Between Years at the SALC and Perception of Autonomy

Another aspect to point out is that if, on the one hand, team work is one of the things student assistants had learned (see answers to questions No. 4 and No. 7), on the other, keeping track of one’s work, negotiating with colleagues and with the manager are felt to be factors hindering one’s autonomy. Although social dimensions of autonomy have been repeatedly pointed out by research (for example, Murray, 2014), these answers indicate that a contradiction is felt between the perception of one’s own autonomy and the constraints of working in groups, having to make compromises and limit one’s own individual decisions in order to find common approaches and ways to work.

Looking at the way the SALC work is organized, there seems to be an inherent contradiction between the need of ensuring already established workflows within a large and fluctuating team and fulfilling an individual’s ideas or expectations while executing tasks. Personally, I share the perception of this contradiction and I address it during personal discussions or staff meetings. I am also aware that, when I welcome or question some of the student assistants’ suggestions considering previous experiences, or institutional factors, I most probably hinder some of the student assistants’ initiatives, contributing to a feeling of frustration among the student assistants, similarly to the frustration I sometimes feel witnessing to recurrent ebbs and flows of ideas and projects over the time. How to overcome this perceived contradiction and at the same time maintain quality in the SALC is certainly one aspect to take into consideration for the SALC future development.

Another aspect these answers point out is that the perception of having space for autonomy or not may diverge according to the student assistants’ understanding of and their attitude towards autonomy: those who understands autonomy as the opportunity to choose their priority and manage the tasks to complete independently perceive their work at the SALC as autonomous; others who understand autonomy as the possibility of working without supervision don’t feel autonomous at the SALC.

Another factor influencing the student assistants’ perception of autonomy is their personal attitude towards the work: I often notice that while some student assistants show initiative and involvement, others have a more passive / reactive attitude and, instead of being proactive, wait for the manager assigning them tasks. This attitude may be related to the student assistants’ personal context or life situation: having other priorities than the job at the SALC, having another job or other personal and interpersonal factors may influence a student assistant’s attitude and, consequently, affect their relationships with their colleagues and supervisor. This is obviously reciprocal and may function as an attractor. When I notice that a student assistant is not inclined to take over a project, I am likely to abstain from encouraging them to go beyond the tasks required by the daily routine, which, in turn, may lead to their impression that initiative is not welcomed. In this regard an individual perception of autonomy should be considered in light of the complex dynamic systems each individual is part of.

The student assistants’ overall opinion on their work

According to the answers to questions No. 7 (What did you appreciate most while working at the SALC?) and 8 (What did you miss?) the student assistants appreciated the collegial atmosphere (the colleagues, eight answers, the atmosphere, five answers), the team work (seven answers), the contact with the students learning at the SALC (six answers), and the opportunity to advise them (seven answers) (see Table 5). On the other hand, while some of the student assistants were fully satisfied with their work at the SALC (seven answers), others missed more challenges, more projects (five answers), more manifold tasks (two answers), and creativity (one answer). Two of them also pointed out lack of motivation and responsibility among their colleagues (two answers), sometimes lack of communication among student assistants and between student assistants and manager (one answer), and having to report about one’s work (one answer) (see Table 5). Again, the variety of these answers may be explained by different attitudes towards and degrees of involvement in the work at the SALC. In addition, different degrees of autonomy and responsibility within a team may also affect the whole team work and its development; thus, lack of motivation and / or communication among the colleagues can have a negative impact on the group.

Table 5 .Things Student Assistants Appreciated or Missed at The SALC

Learning for life

What did student assistants get out from their work at the SALC? According to their answers to question No. 9, some of them learned to work in a team (six answers), acquired competences regarding language learning and language learning materials (five answers), gained self-awareness and self-confidence (four answers), developed self-reflection and the management skills (five answers), communication (three answers) or advising skills (two answers). The feeling of having enjoyed working at the SALC is also explicitly mentioned (four answers) (see Table 6). On the whole, several answers outline aspects which are intrinsic to autonomy: self-awareness, self-confidence, reflection and the capacity of managing tasks independently. Therefore, autonomy can be at least implicitly considered to be part of what some student assistants learned in the end.

Finally, the comments of ten student assistants outline the affective and social aspects of their experience at the SALC: “It was a great job”, a “I had a wonderful time”, “I enjoyed it very much”, “I think about it very often”, “I am grateful” and “Thank you for the wonderful time”.

Table 6. What Student Assistants Got Out For Themselves

Reflection on practice and autonomy

Reflection on practice and autonomy

Some of the student assistants’ comments help me to evaluate the reflection processes put in place at the SALC. On the one hand, some of the comments enthusiastically emphasise the freedom and the trust experienced and the motivation arising from this. On the other hand, other comments highlight the sense of control and the burden of having to report on one’s work. (see participant No. 13 “In the everyday routine very autonomous, long-term projects had to be discussed with the manager.”; No. 3 “Sometimes I did not like to have to report on my work. It was as if one were distrusted, as one did not work properly.”).

Looking at the reflection processes in the light of these results, I think it would be advisable to find different ways to integrate reflection in the SALC work without making it a burden for student assistants. Similarly to what may happen in the language classroom, where some learners are willing to engage in reflection on their learning process through learning journals or other tools, whereas other are more reluctant, a balance should be found between reflection and actual work. To do this, it could be negotiated with student assistants on which projects the reflection should focus; in addition, individual differences could be taken into account, thus allowing different ways of reflecting, for example through individual or group discussion or written reflection. This would make the reflection process more flexible and adapt it to better suit individual priorities and preferences of student assistants. A clear distinction between tasks allowing more creativity and autonomy and tasks with a more limited space of manoeuvre could also make the stakes of the work at the SALC more transparent to the student assistants themselves, and thus help them to find a more aware attitude towards their work.

Conclusions

The SALC is intended to be a space for exchange and experimentation, a community of practice whose participants are encouraged to act, reflect, and evolve in their work and in their personal development. The student assistants’ autonomy and reflection are encouraged through specific training, individual dialogues, group discussion and communication, as well as a reflective practice model following a planning, implementation and evaluation cycle. However, as the results of the survey show, the student assistants’ perception on their personal and professional gain through their service at the SALC may differ depending on their understanding of autonomy and on their attitude towards their work and the reflection process. Although the collegial atmosphere, the team work, the opportunity to undertake meaningful projects are perceived as enjoyable and rewarding by the majority of the student assistants asked, the need to keep track of one’s work, to communicate with colleagues and negotiate with the manager, and in some cases the daily routine are by some considered as hindering their autonomy.

The results of the questionnaire stimulate me to think about how I could improve some reflection processes: in order to respect the needs and natural attitudes of the student assistants on the one hand and to meet the institutional function of the SALC on the other, a balance between autonomy and control should be aimed at, more room for individual choices should be negotiated, taking into account both institutional constraints and collegial decisions, and reflection should be encouraged in the right dose. The contradiction between the perception of one’s autonomy and the constraints of having to negotiate within the group could be softened by explicitly working on team building and on a common understanding of autonomy. An inspiration in this respect comes from Murray (2018): in order to facilitate the emergence “self-enriching complex dynamic ecosocial systems”, we need to nourish a common vision, distribute control, encourage reciprocity and interaction.

On the personal level, managing a SALC with student assistants means to find a balance between guidance and room for individual initiatives, between continuity and innovation, with patience, curiosity and dedication.

Notes on the Contributor

Maria Giovanna Tassinari is Director of the Centre for Independent Language Learning at the Language Centre of the Freie Universität Berlin, Germany. Her research interests are learner autonomy, language advising, and affect in language learning. She is co-editor of several books and author of articles and chapters in German, English and French.

References

Allwright, D., & Hanks, J. (2009). The developing language learner: An introduction to exploratory practice. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). Promoting reflection in learning: A model. In D. Boud, R. Keogh, & D. Walker (Eds.), Reflection: Turning experience into learning (pp. 18-40). New York, NY: Routledge Falmer.

Dam, L. (1995). Learner autonomy 3. From theory to classroom practice. Dublin, Ireland: Authentik.

Dewey, J. (1963). Experience and education. New York, NY: Collier Books.

Estrada, M. I. (2012). Impacto del centro de autoaprendizaje de la Universidad Libre de Berlín (SLZ) en el desarrollo de la autonomía de aprendientes de lenguas extranjeras: creencias y perceptiones de estudiantes de ELE en el contexto universitario alemán. Berlin: Freie Universität.

Freire, P. (1973). Education for critical consciousness. New York, NY: Seabury Press.

Friesen, A., Tassinari, M. G., & Ulmer, K. (2011). International und studiengerecht: das Tandemprogramm an der Freien Universität Berlin. TANDEM FUNDAZIOA Neuigkeiten, 49, 51-68.

Hanks, J. (2015). ‘Education is not just teaching’: Learner thoughts on Exploratory Practice. ELT Journal, 69(2), 117-128. doi:10.1093/elt/ccu063

Hujová, P. (2014). Influencia del tipo de personalidad de los participantes en la satisfacción con la experiencia de tándem. Berlin: Freie Universität.

Kohonen, V. (2001). Towards experiential foreign language education. In V. Kohonen, R. Jaatinen, P. Kaikkonen, & J. Lehtovaara, Experiential learning in foreign language education (pp. 8-60). London, UK: Pearson Education.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Little, D. (1991). Learner autonomy 1. Definitions, issues and problems. Dublin, Ireland: Authentik.

Little, D., Dam, L., & Legenhausen, L. (2017). Language learner autonomy. Theory, practice and research. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Lopez, L. (2013). El papel del asesor en el acompañamiento de procesos de aprendizaje en autonomía de los usuarios del Centro de autoaprendizaje del Centro de idiomas de la Universidad Libre de Berlín. Berlin: Freie Universität.

Morrison, B. (2008). The role of the self-access centre in the tertiary language learning process. System, 36(2), 123–140. doi:10.1016/j.system.2007.10.004

Murray, G. (Ed.) (2014). Social dimensions of autonomy in language learning. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Mcmillan.

Murray, G. (2018). Self-access environments as self-enriching complex dynamic ecosocial systems. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 9(2), 102–115. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun18/murray

Van de Poel, K. (2018). Action research for learner autonomy in situ: From idea to dissemination. In C. Ludwig, A. Pinter, K. Van de Poel, T. F. H. Smits, M. G. Tassinari, & E. Ruelens (Eds.), Fostering learner autonomy. Learners, teachers and researchers in action (pp. 24-36). Hong Kong: Candlin & Mynard.

Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (Eds.) (2013). Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. London, UK: Sage.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professional think in action. London, UK: Temple Smith.

Tassinari, M. G. (2016). Emotions and feelings in language advising discourse. In C. Gkonou, D. Tatzl, & S. Mercer (Eds.), New directions in language learning psychology (pp. 71-96). Basel, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing Switzerland.

Tassinari, M. G., & Ciekanski, M. (2013). Accessing the self in self-access learning: Emotions and feelings in language advising. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(4), 262-280. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/tassinari_ciekanski1.pdf

Appendices

See PDF version