Leni Dam, (Formerly) University College, Copenhagen and Northern Zealand, Denmark

Dam, L. (2018). Learners as researchers of their own language learning: Examples from an autonomy classroom. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 9(3), 262-279. https://doi.org/10.37237/090303

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

Learners have in the past quite often been involved in research projects as co-researchers, and have, for example, provided researchers and teachers with data. This paper describes how learners can be systematically supported in becoming researchers of their own language learning in an autonomy classroom. In doing so, the similarities between the work/research cycles involved when developing language learner autonomy and when supporting learners in becoming researchers of their own language learning are exemplified. Furthermore, useful and necessary tools and pre-requisites for the two parallel processes in question are pointed out and illustrated. After two examples with learners as co-researchers at beginners’ level and one example of a complete research cycle from one student at intermediate level, the paper concludes that a learner developing his or her autonomy is at the same time researching his or her own language learning. As a corollary the teacher’s role changes from an action researcher to a co-researcher in the autonomy classroom.

Keywords: Action research, learners as researchers, co-researchers, research cycles, language learner autonomy, teacher roles, learner roles, logbook data, secondary school, classroom management.

There is a tendency for the role of learners to change when it comes to researching language learning and teaching. It used to be the case that learners just provided the data to be dealt with in a project. In recent years, though, learners have become more actively involved in connection with research; they have become co-researchers (Pinter & Mathew, 2016). This paper, however, the main ideas of which were presented at the AILA conference in Rio de Janeiro 2017, goes a step further. It describes and exemplifies how learners can systematically be supported in becoming researchers of their own language learning in an autonomy classroom.

An Autonomous Learning Environment

The autonomy classroom and its learners discussed in this paper are described at great length in many publications, e.g. Dam (1995) and Little, Dam and Legenhausen (2017), just to mention the first and the latest one. Therefore, only those aspects of developing learner autonomy which are relevant when talking about learners being researchers of their own language learning are focused upon in this paper.

An autonomous learner

The following description of an autonomous learner has proved adequate and useful for the work with developing the learners’ autonomy:

An autonomous learner is characterized by a readiness to take charge of his/her own learning in the service of his/her needs and purposes. This entails a capacity and a willingness to act independently and in co-operation with others, as a social responsible person (Dam, Eriksson, Little, Miliander, & Trebbi, 1990, p. 102).

In order to develop this capacity, it is of utmost importance that learners are actively involved in their own learning. They have to be aware of what they do, why they do it, how they do it and how to make use of the outcome – the basis for action research. They must become “shareholders of their own learning” (Rogers, 1969, p. 9).

In addition, an autonomous learning environment will prepare learners for lifelong learning – an important issue also when the talk is about a continuous language development outside institutional environments:

No school, or even university, can provide its pupils or students with all the knowledge and the skills they will need in their active adults lives. …It is more important for a young person to have an understanding of himself or herself, an awareness of the environment and its workings, and to have learned how to think and how to learn (Trim, 1988, p. 3).

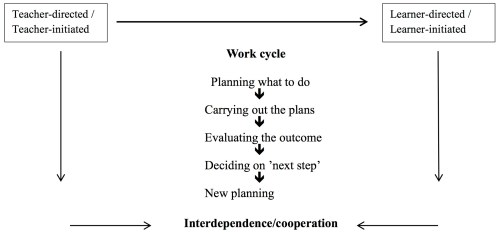

Getting learners actively involved in their own learning and preparing them for lifelong learning is first and foremost the teacher’s responsibility (Dam, 2003). The task might be supported by the following, simplified model (Figure 1) which is a model reminiscent of the work cycle in action research, as will be demonstrated below.

A simplified model for developing learner autonomy

The steps in the work cycle in the centre of the model—planning what to do / carrying out the plans / evaluating the outcome / deciding on ‘next step’—are phases included in any teaching / learning environment. They can be carried out by the teacher in a teacher-directed and teacher-initiated teaching environment without involving the learners in any decisions concerning the work undertaken (indicated by the downward arrow to the left of the figure). The aim in the autonomy classroom, however, is to move towards a learner-directed and learner-initiated learning environment where the learners can and will be involved in managing their own learning process (the downward arrow on the right). This move from a focus on the teacher’s teaching to a focus on the learners’ learning is indicated by the arrow at the top between the two boxes – a process also described as ‘letting go’ for the teacher and ‘taking hold’ by the learners (Page, 1990, p. 91).

The initiatives as regards ‘letting go’ and ‘taking hold’ (Little, Dam, & Legenhausen, 2017, pp. 71-93) start out from the teacher – the learners are so-to-speak ‘forced’ to act. However, when it comes to making new decisions regarding ‘next steps’ these will always depend on the learners’ reactions – observed by the teacher during an activity and/or expressed by the learners in the evaluation following an activity. From the very beginning of developing learner autonomy, there is thus a constant interdependence and cooperation between what the teacher does and what the learners do (indicated at the bottom of the model).

Figure 1. A Simplified Model for Developing Learner Autonomy (Dam, 1995, p. 31)

Comparing and Combining Development of Learner Autonomy and Action Research

A model for action research

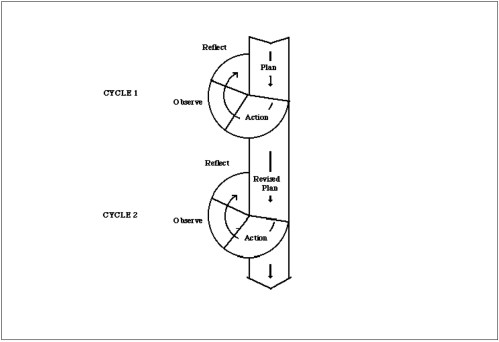

If we compare the work cycle when developing learner autonomy in Figure 1 with the cycle for action research by Kemmis and McTaggart (1988) and referred to in Hopkins (2008) in Figure 2, the similarities between the two cycles are evident. In both cases it is a matter of an on-going and never-ending process where one work or research cycle leads on to the next cycle. Furthermore, each cycle includes four steps of action – labelled slightly differently, though, in the two models.

Figure 2. Action Research Cycle (Kemmis & McTaggart, 1988, referred to in Hopkins, 2008, p. 51)

One could claim that developing learner autonomy is a form of action research for the teacher as well as the learners. In that case, it is therefore feasible to combine the contents of the two cycles into one cycle (Figure 3).

Instead of a move from a teaching- and teacher-directed teaching environment to a learning- and learner-directed learning environment when developing learner autonomy, Figure 3 includes a similar move from the teacher as a researcher of her own teaching towards the learners becoming researchers of their own learning (the arrow at the top of the figure). Furthermore, the interdependence and cooperation between the teachers’ decisions and initiatives and her learners’ reactions and responses in the process of action research in the autonomy classroom is the same in both cases. In the research cycle in Figure 2, ‘evaluation’ – the pivot of learner autonomy (Dam, 1995) is implied in reflection. This is taken into account in the steps included in the work cycle / research cycle in Figure 3.

Figure 3. A Work Cycle for Action Research in the Autonomy Classroom

In the next, few paragraphs some useful and necessary tools as well as some pre-requisites for making the learners willing to take over responsibility for their own learning as well as researching it will be briefly described.

The use of a logbook

Documentation of the ongoing process—what you do, why you do it, how you do it, and with what result—is essential for action researchers (developers of learner autonomy), be it teachers or learners. It is important for the teacher to keep a log containing the steps she decides on when planning, for her observations when her initiatives are carried out, and for her reflections / evaluations leading to ‘the next step’. It is equally important that each learner keeps a personal log of his or her individual ‘journey of learning’ – similarly to a ship’s log for a voyage (Dam, 2009, pp. 125-144).

A structure of a lesson, a period or a research cycle

Unfortunately, ‘chaos’ is very often a term cropping up in connection with ‘the autonomy classroom’. However, in order for the learners to take over the management of their own learning, some kind of structure—transparent to the learners—of the ongoing undertakings in the classroom is crucial. One way that has proved useful in this respect is to divide the time available for a lesson, for a period, or for a research cycle into three well-defined periods: teacher’s time, learners’ time, and ‘together’ time (Little, Dam & Legenhausen, 2017, pp. 80-82).

Teacher’s time. As the teacher’s aim is to involve her learners actively in their own learning, the teacher’s time will to a large extent be used for suggesting activities for the learners to try out and later to choose from according to individual needs and purposes. The teacher’s choice of activity will depend on curricular demands, but a new activity can also be the result of insights gained from learners’ evaluations of a previous activity, or from research data provided by the learners as co-researchers (see research cycles 1 and 2).

Learners’ time. In ‘learners’ time’ the learners will work individually, in pairs or in groups with activities initially suggested by the teacher. The learners will, however, always be seated in groups in order not only to facilitate the social processes of learning, but also to become more independent of the teacher – two reasons that will support them in managing their own learning. Gradually, they will take over more and more responsibilities for the various steps in the work/research cycle. As soon as they are capable of carrying out the whole cycle on their own, a plan for the work to be carried out will be entered on a poster—visible to everybody—as some kind of contract. The plan will specify:

- Who is involved in the plan/contract?

- What kind of work / project will be carried out?

- What is the expected outcome?

- How much time will be needed?

The work with these plans will be documented in the learners’ logbooks and will often run parallel with separate contracts focusing on the individual learner’s needs in connection with his/her linguistic development (see research cycle 3 below).

Together time. In ‘together time’, the sharing of observations and reflections / evaluation – based on logbook entries from learners and teacher – will take place. ‘Together time’ will also include presentations of work cycles carried out by groups of learners. These presentations will be based on the contracts on posters described under ‘learners’ time’. Last but not least, this shared evaluation time will provide space for learners’ ideas about which ‘next steps’ in the research cycles might be relevant.

Learners as Co-researchers and Researchers of their Own Language Learning

The class in question

The research cycles described below were carried out with a mixed-ability class of 21 Danish learners from their beginning of learning English in their 5th grade at the age of eleven till their 8th grade – the period of the LAALE project (Little, Dam, & Legenhausen, 2017, pp. 121-157). In the first two years the students had four 45-minute lessons per week (two double lessons). The following two years they had three lessons of 45 minutes per week. The school is a Danish comprehensive school in a suburban area south of Copenhagen (Dam, 1995, p. 8).

The data

The data referred to in the research cycles come from the logbooks of the learners in question, from entries in the teacher’s logbooks, and from the evaluation questionnaire used in research cycle 2 (Appendices A and B).

Learners as co-researchers at beginners’ level: Two examples

The move from a learning environment where the teacher is the only action researcher to one where the learners are actively involved in researching their own language learning will have to be taken in small steps similar to the process of developing learner autonomy.

In my case, I started out by involving my learners as co-researchers as follows. Before any data collection, my learners would always be made aware of the objectives for the questions asked. Furthermore, they were involved in setting up the data collection procedures. Below I shall report on two action research cycles that I carried out at beginners’ level – first year of English.

Research cycle 1: Making learners aware of research objectives. My first and most important research questions were: How can I get my learners involved in their own learning? How can I make them aware of why and how they learn English? Therefore, as early as in their third week of learning English I got them involved as described in Figure 4. Apart from providing me with the insights that I needed, the questions posed were meant to support one of the main principles when developing language learner autonomy: Involve the learners’ identity and previous knowledge. This will lead to improved self-esteem and readiness to take over responsibility for one’s own learning.

| Planning: Ask learners to answer the questions: Why do I learn English? How do I learn English?

Action: Learners write their answers in L1 in their logbooks. The individual answers are gathered and translated into L2 by the teacher and distributed to each learner. The combined lists of answers are glued into the individual logbooks. Observation/Evaluation: All the learners were actively engaged in the activity. Even though the answers varied in length as well as in diversity, every single statement provided me with an insight as regards the individual learner’s involvement in and awareness of their own learning. Planning ‘next step’: How can/will I make use of the data? |

Figure 4. Research Cycle 1

‘Next step’: New plans / new research cycles following research cycle 1. As mentioned, the individual answers varied a lot as regards ‘the why’ as well as ‘the how’. When it came to ‘the why’, one learner had just written “Because I have to”, where others had come up with several reasons (Appendix A). In order to make all the learners aware of the wide spectrum of reasons that they as a group had come up with, a complete list of answers was glued into their logbooks. Having all the arguments given by their peers in front of them, each learner was asked to place a tick next to a reason for learning English that he/she could also subscribe to. A series of new research cycles developed from there.

The responses to ‘the how’ were treated in a slightly different way due to the fact that they contained the learners’ own practical ideas for learning English. Looking at the list of answers, the learners were asked to choose three ways of learning English that they could make use of immediately outside school. Chosen ideas and strategies were: “Speak English with my mother when we do the washing-up”; “Find English words”; “Watch English films”. In class, the various answers gave rise to a series of activities dealing with ‘how to learn English’. These data formed the basis for another, i.e. additional, research cycle focusing on the linguistic development of the learners. In other words, the learners were from now on involved in parallel research cycles.

Research cycle 2: Learners as initiators of data collection procedures as well as providers of research data. After eight weeks, i.e. 30 lessons of English, I felt that it was time to evaluate this period of learning English. For this purpose, I could of course have made up a questionnaire myself, but my aim was to involve my learners as co-researchers of their own learning. I, therefore, asked myself the following research question: How can the learners be involved in evaluating their first eight weeks of learning English? Figure 5 shows the research cycle.

| Planning: Make the learners reflect on their own learning, asking them to formulate questions concerning their first eight weeks of learning English. The questions are to be used for a questionnaire for the whole class.

Action: Individually, the learners write down in their logbooks as many questions as they can think of. The teacher systematizes the questions and places them in a questionnaire designed by her. [See Appendix B for examples of questions as well as the format of the questionnaire.] Observation/Evaluation: Again, the learners are very motivated and engaged in the task: Reflecting on their own learning. As a teacher, I would never have thought of asking some of the questions e.g. “Has it been “cosy” to learn English?” No doubt, this activity was the crucial step for the learners towards becoming researchers themselves. Reflection / Planning ahead: The next step will be that the learners plan and carry out work cycles individually / in pairs / in groups. The plans will be made public to the class on posters. |

Figure 5. Research Cycle 2

Learners as researchers of their own language learning

In the course of learning English, the learners become aware of their linguistic needs while being engaged in various activities. They see, for example, the need to improve their fluency when engaged in group discussions, or when peers draw their attention to weaknesses when they present project reports. This growing awareness results in a series of questions that learners ask themselves:

- What do I have to improve? / What do I want to improve? / How do I know? / What is the challenge?

- What will / can I do about it?

- With what result?

- What’s the next step?

These questions, however, correspond to the steps in a research cycle. In other words, the learners have by now reached a stage where they are researchers of their own language learning.

Research cycle 3: An example of an individual learner’s research cycle. The last illustrative example is a research cycle carried out by a 14-year-old learner in his fourth year of learning English. The class had by then reached a stage where they had all entered contracts for their own linguistic development in their logbooks on a regular basis. Karsten’s needs for ‘improvement’ at this point derived partly from peer-assessment of an oral report in class, partly from peer-corrections of one of his essays. Figure 6 shows Karsten’s research cycle over a period of four weeks. The text, which is unedited, is taken from his logbook. (For more examples, see Dam, 2006).

| Planning:

Tuesday, 9th April. My contract for April: I will read aloud from my book when I am sharing homework to practice my articulation. I will write some stories as homework, to practice my spelling and written language. [In the meantime new groups had been established. The learners were asked to find somebody that they could help, or somebody who could be of help to them. Michael, a weak learner, and Karsten (a strong learner) decided to work together. It is noticeable how Karsten while working with Michael (the much weaker learner) managed to support his own aims.] Tuesday, 16th April. Michael and I is going to work with stories where spelling , and advanced language is the key factors, we’re going to practice our articulation by talking and reading aloud to eachother[sic], but most important, we’re going to talk English all the time, and keep it that way. Action [same day]: Homework: Read in “The X-rays” f.p. 16. Find a text and practice reading it. Plan for Monday: A good long sharing home (talking) and an improved wordsnake with long words (spelling). Observation / Reflection [same day]: Comments on today’s work: Michael and I is good friends, and therefore good partners in English. I think it’s a good way to work, by choosing a couple of things you wish to be better at, and practice them with your sidekick. [In the following lessons the two boys continued in the same way with carrying out activities of their own choice which supported their aims / contracts. After four weeks, it was time to look at and evaluate the contract / the work cycle.] Evaluation: Tuesday, 30 April [after 4 weeks]. Share homework with Michael. Michael had read a couple of pages in “Ivanhoe”, and he read a-loud to me, and I must say, that it was very, very good read, he knew all the words and was very articulated. Looking at contracts: I think I have lived up to my contract, because I have done what I said I would, I’ve read aloud, written stories, practiced articulations by speaking a lot with Michael. Next step: [Forming new groups. Let the learners in the new groups set up plans and contracts for their work in these groups as well as new individual contracts.] |

Figure 6. An Example of an Individual Learner’s Research Cycle

Forming new groups and setting up new plans/contracts. On May 6th, i.e. the following week, Karsten entered in his logbook: I would like to work with Lasse, Michael and Lars because we had a blast last time, but the product wasn’t as good as it could be, and we would like to improve that. I would like to make a video programme because I have never done it before. In other words, a new ‘group’ work/research cycle had begun. However, from Karsten’s logbook entries it can also be seen that he continuously pursues his personal goals within the group work.

The teacher as co-researcher in the autonomy classroom

At this stage where the learners have ‘taken hold’ and are setting up their own individual contracts as well as group contracts, there is of course still need for the teacher’s involvement in the learning process and the development of learner autonomy. However, her role has now changed from being the main initiator when setting up research cycles towards a role as a co-researcher. Her role is to a large extent to support research cycles initiated by the learners. This means, for example, that she will comment on the learners’ contracts as well as on their reviews of their contracts in their logbooks. Here are her comments in connection with Karsten’s evaluation of his research cycle and its results on 30th April:

Dear Karsten,

I agree with you; it sounds as if you have worked determinedly with your contract – and from the tape-recordings I can tell that your articulation has improved immensely.

Love Leni

Conclusions

A prerequisite for including her learners in action research of their own language development is that the teacher, herself, IS an action researcher. It is first when the teacher continuously asks the questions: What do I do? Why do I do it? How do I do it? that she is truly capable of supporting her learners in asking the same questions. She must also in this case be the model in the language classroom.

Furthermore, it has been stressed that the learners must be respected and trusted when they are taking over responsibility for their own learning. The same trust is needed when learners become researchers of their own learning.

Moreover, the similarity between the two processes – as has been outlined above – is emphasized when looking at the following features of a ‘learner as researcher’. A learner capable of researching his/her own language learning is characterized by:

- a readiness to take charge of one’s own learning in the service of one’s needs and purposes

- an awareness of what to learn and how to learn

- a capacity and willingness to act independently as well as in co-operation with others – in the process of language learning.

This, however, is exactly what characterizes an autonomous language learner. In other words, developing language learner autonomy and supporting learners in becoming researchers of their own language learning are parallel as well as deeply interwoven processes.

Notes on the contributor

From 1973 till 2007, Leni Dam practised language learner autonomy in her own English classes at a Danish comprehensive school near Copenhagen. From 1979 she was in addition employed by University College, Copenhagen, doing INSET and being in charge of innovative school projects. Together with Lienhard Legenhausen, Germany, she carried out the LAALE research project (Language Acquisition in an Autonomous Learning Environment) from 1992-1996. From 1993-1999, she was co-convenor of the AILA Learner Autonomy in Language Learning Scientific Commission, and from 2008-2016 she was co-coordinator of the IATEFL Learner Autonomy Special Interest Group. She has published widely. Especially her first book (Dam, 1995) and her latest one together with David Little and Lienhard Legenhausen (2017) are landmarks in her publications. After her retirement in 2007, she has continued to publish, to give talks and to run work-shops – in this way continuing to increase her insights into the development of language learner autonomy and related areas.

References

Dam, L. (1995). Learner autonomy: From theory to classroom practice. Dublin, Ireland: Authentik

Dam, L. (2003). Developing learner autonomy: The teacher’s responsibility. In D. Little, J. Ridley & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Learner autonomy in the foreign language classroom: Teacher, learner, curriculum and assessment. Dublin, Ireland: Authentik.

Dam, L. (2006). Developing learner autonomy – looking into learners’ logbooks. In M. Kötter, O. Traxel & S. Gabel (Eds.), Investigating and facilitating language learning (pp. 265-283). Trier, Germany: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag.

Dam, L. (2009). The use of logbooks – a tool for developing learner autonomy. In R. Pemberton, S. Toogood & A. Barfield (Eds.), Maintaining control: Autonomy and language learning (pp. 125-144). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Dam, L., Eriksson, R., Little, D., Miliander, J., & Trebbi, T. (1990). Towards a definition of autonomy. In T. Trebbi (Ed.), Third Nordic workshop on developing autonomous learning in the FL classroom (p. 102-108). Bergen, August 11-14, 1989. Report. Bergen, Norway: Institutt for praktisk pedagogikk. Universitetet i Bergen. Retrieved from https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/al/research/groups/llta/research/past_projects/dahla/archive/trebbi-1990.pdf

Hopkins, D. (2008). A teacher’s guide to classroom research. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1988). The action research planner. Waurn Ponds, Australia: Deakin University Press.

Little, D., Dam, L., & Legenhausen, L. (2017). Language learner autonomy: Theory, practice and Research. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Page, B. (Ed.) (1992). Letting go, taking hold. A guide to independent language learning by teachers for teachers. London, UK: CILT.

Pinter, A., & Mathew, R. (2016). Children and teachers as co-researchers: A handbook of activities. London, UK: British Council, ELT Research Papers 16.03.

Rogers, C. (1969). Freedom to learn. London, UK: Merrill Publishing Company.

Trim, J. (1988). Preface. In H. Holec (Ed.), Autonomy and self-directed Learning: Present fields of application (p. 3). Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe.

Appendix A

Data from Research Cycle 1: Answers from 3 Learners

In order to show the diversity in content as well as length, the answers from three students at different levels of their linguistic development have been included in this appendix as well as in Appendix B. The three students are: Susan, a dyslexic student and very weak at the beginning of learning English, Emrah, an average student of Turkish origin and Birgitte, a student with a very supportive family and with an impressive English vocabulary already at the beginning of learning English. Excerpt 1 shows the answers to ‘Why do I learn English’? Excerpt 2 shows the answers to ‘How do I learn English’?

| Why do I learn English?

Susan (weak): If I one day am going abroad. It is a “cosy” language. Nearly everybody can speak English. Emrah (average): Because when I am abroad I can talk to people and if anything happens to our car I can tell somebody. Birgitte (advanced): I want to learn English because I can make use of it later in life. I can talk to people from other countries. Then I can travel without needing anybody to translate for me. Then I can understand English and American films. Then I can write to my Polish penfriend. Then I can read English texts and posters and advertisements. |

Excerpt 1. Answers to ‘Why do I Learn English’?

| How do I learn English?

Susan (weak): Speak more English. Also work in groups. Emrah (average): I can watch many English films. And read many English books, and look in an English magazine and find some English names that I can write to. Birgitte (advanced): When I read English books and watch English films and am on holidays in England and write English stories and write letters to my Polish pen friend and be active in the English lessons and play computer with English text and look in English dictionaries and speak English with my mother and father and read English advertisements and posters and read magazines with English and American rock-groups and find out what it means. Listen to songs in English and join in and look at the texts if you have them and cut out pictures and glue them into a book and write in English what is in the picture. |

Excerpt 2. Answers to ‘How do I Learn English’?

Appendix B

Evaluating the First Eight Weeks

The evaluation questions selected for this data derive from the same three students who provided the answers to ‘why’ and ‘how’. Unfortunately, Emrah was ill on the day of the evaluation; therefore his answers to the questionnaire itself could not be included. Excerpt 3 shows the questions for evaluating the first eight weeks of learning English, suggested by the three learners in question.

| Susan: Was it fun? Has it been “cosy”? Do you think that you have learned something? Do you like English?

Emrah: Has it been fun? Has it been bad? Did you learn a lot of English? Birgitte: If you could decide yourself whether to have English or not, would you choose English? Has it been fun? Do you like the English lessons? What is the best thing about learning English? Would you like to stop now if possible? Would you rather have had a list with all the words and then read them and learn them by heart? Would you have preferred a private teacher? |

Excerpt 3. Evaluation Questions Suggested by Three Learners

The evaluation questionnaire included twenty questions. However, only two of them are shown in Excerpt 4 just to illustrate the format of the questionnaire. It includes: the question asked, the rating scale with the marks entered by the students, and the answers given by Susan and Birgitte only – as Emrah was away from school on that day.

| 1. Has it been fun to learn English?

Yes-l-l—————————————————————————————–No Why? • It is a good language. • It is fun to know another language. I am glad that we did not have a list of words to learn by heart. 3. Have you enjoyed learning English? Yes-l—————————————-l————————————————–No Why? • You feel pretty “cosy”. • Not exactly “enjoyed”, but it has been good fun. |

Excerpt 4. Extract from the Evaluation Questionnaire