Yukari Rutson-Griffiths, Hiroshima Bunkyo Women’s University, Japan

Mathew Porter, Fukuoka Jo Gakuin Nursing University, Japan

Rutson-Griffiths, Y., & Porter, M. (2016). Advising in language learning: Confirmation requests for successful advice giving. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(3), 260-286. https://doi.org/10.37237/070303

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

One of the roles of language learning advisors is to help language learners become more autonomous and one crucial way to achieve this is to facilitate reflection on their learning through dialogues in advising sessions. Although previous studies on advising skills have provided practitioners with invaluable resources for their professional development, more studies on actual interactions can further illuminate the nature of advice-giving to support or better inform existing advising frameworks. This research uses conversation analysis to examine a naturally occurring advisor-learner interaction to uncover how the conversational participants achieve shared understanding. It was found that a series of confirmation requests help adjust and maintain the participants’ mutual understanding while the conversation unfolds. The findings of this study suggest that more research examining authentic dialogue using conversation analysis will shed light on uncovering the mechanisms underlying the successful provision of appropriate advice in language learning and consequently contribute to the professional development of advisors in the future.

Keywords: advising in language learning, conversation analysis, professional development

The role of language learning advisors (hereafter, advisors) is often misunderstood by those outside the field of self-access language learning and much has been written to show how the role of advisor (or counselor) differs from that of a teacher (Carson & Mynard, 2012; Gardner & Miller, 1999), which has helped to legitimize and define the field of advising in language learning and support the training of novice advisors. A common misconception about advisors is that they give advice to learners about immediate problems encountered during language study, the kind of assistance that writing centers or classroom teachers already provide. Although it may be the case that immediate problems are addressed during an advising session, one of the advisor’s aims is to encourage reflection about the learning process so that learners ultimately become able to manage their own learning more effectively.

Advisors encourage reflection through dialogue with learners. Mynard (2012) has said that “it is through this mediational dialogue that advisors and learners can work together to uncover expectations, motivational factors, prior beliefs, experiences, individual differences and preferences while helping an individual to reflect, understand and plan” (p. 43). This reflective dialogue, according to Kato and Mynard (2015), can create opportunities for learners to transform their beliefs and lead to further growth.

Advisors use a variety of skills during this reflective dialogue with learners and these skills are usually discussed in terms of their purpose within the discourse (Carson & Mynard, 2012). Descriptions of these skills often consider both the verbal and nonverbal message and usually include reflective skills that help communicate understanding and empathy such as mirroring, paraphrasing, and summarizing (Mozzon-McPherson, 2012; Stickler, 2001). Kelly (1996) listed these and other skills in her influential article introducing macro- and micro-skills for language counseling (Appendix A). In general, macro-skills support the institutional agenda, namely developing autonomy and management of the advising session, while micro-skills are concerned with reflective listening and building rapport with the learner. Kelly’s skills have played an invaluable role in advisor training and professional development because they give an idea of what skills advisors can employ to guide advising sessions, connect with learners, and provide appropriate support, and they can also be used as a framework for reflecting on one’s advising practice (McCarthy, 2012; Morrison & Navarro, 2012).

There are a number of works by experienced advisors (Kato & Mynard, 2015; Mozzon-McPherson, 2000, 2012) illustrating how skills such as those described by Kelly can be employed in spoken advisor-learner interactions. Within the field of advising in language learning, however, Carson (2012) has called for further investigations into advisor-learner dialogue using “more informed and more in-depth discourse analysis, and the use of other methodologies” (p. 299). Having studied the reflections of advisors on their own advising sessions using Kelly’s skills as a basic framework, Morrison and Navarro (2012) also suggest reconsidering Kelly’s framework. This paper does not deny the valuable contribution to the field of advising in language learning that previous research into advising skills has provided, but as Peräkylä and Vehviläinen (2003) have found in studies on medical and counselling settings, experts’ knowledge or ideas about interactions in their field can differ from actual interactions and argue that conversation analysis (CA) can contribute to filling that gap.

Conversation Analysis

CA is a methodology for analyzing naturally occurring spoken interaction, as opposed to scripted or idealized discourse. It is often used to investigate spoken interaction in institutional settings such as health care, counseling, and news interviews, and has been used to identify and describe the phenomena of turn-taking, repair, and preference organization. CA begins with an audio or video recording of a naturally occurring spoken interaction which is used to create a detailed transcript that includes paralinguistic features such as pitch, rate, amplitude, and silence as well as nonverbal actions and sounds. Analysts look for recurring patterns of interaction in the transcript that can be used to support the creation of a rule or model to explain the occurrence of the pattern in the interaction.

The distinctive features of CA can be perhaps better outlined by comparing it with other types of analyses. Writing on CA and discourse analysis (DA), Wooffitt (2005) explains that, in general, the focus of studies in CA is “the social organisation of activities conducted through talk” and “the goal of analysis is to examine sequences of interaction, not isolated utterances” whereas DA “is primarily concerned with a broader set of language practices: accounts in talk or texts” (p. 79). He also argues that CA “offers formal analyses at a greater level of detail, and relies upon a distinctive vocabulary of technical terms to capture this detailed organisation” of interactions, comparing it to DA where “the management of interaction per se is rarely the focus of research” (p. 80).

Another point which makes CA distinctive is the way in which researchers see the contexts of interactions and how they position themselves as analysts. Wooffitt (2005) points out that one problem with other types of qualitative analyses of interactions is the validity of the researcher’s interpretations and accuracy of his or her understanding of objective phenomena. The observer perspective and analytical methodology employed in CA, however, overcome this issue. CA sees contributions to the interaction as both context-shaped and context-renewing, meaning that they can only be understood within the contexts they occur and they go on to shape the context in which the next contribution will occur (Seedhouse, 2005). In CA, the aim of a study is to “reveal how participants’ own interpretations of the on-going exchange inform their conduct” (Wooffitt, 2005, pp. 86-87) rather than to interpret such conduct using outside factors chosen by the analyst. To achieve this, analysts use an emic perspective “to determine which elements of context are relevant to the interactants at any point in the interaction” in order to discover “how participants analyse and interpret each other’s actions and develop a shared understanding of the progress of the interaction” (Seedhouse, 2005, p. 166). In other words, analysts examine how participants understand each other by closely observing how participants display their understanding in subsequent turns instead of relying on their own interpretations as observers.

Conversation analysis and advising

Although CA has contributed greatly to the study of spoken interactions in institutional settings, much of the work on advising, let alone language advising, is yet to be seen. However, existing work on advising in other institutional contexts suggests the complex nature of advice-giving. Heritage and Sefi (1992), for instance, in their study on naturally occurring talk between health visitors and new mothers, have shown the ways in which advice delivered by experts can be difficult for their advisees to accept. They explained that in such cases the health visitors tend to initiate advice-giving rather than letting those mothers request advice based on their specific needs, and they rarely acknowledge the mother’s competence in parenting. Studying academic counseling sessions, He (1994) reported that the practice of withholding advice, which is sometimes preferred in academic advice-giving settings so as to help advisees make decisions by themselves, might cause a clash of expectations between advisors and their advisees.

Given that the act of advice-giving entails some potential problems, it requires cautious preparation. Analyzing the talk between counselors and students in career-guidance training sessions, Vehviläinen (2001) has argued that stepwise entry minimizes the potential resistance of advice. In the course of stepwise entry to advice-giving, question-answer sequences are used by a counselor to seek a student’s perspective before giving advice. Her study demonstrated that counselors topicalize some issues covered in the previous talk by asking students questions or pointing out problems, and attempt to elicit students’ opinions or ideas regarding these issues. This then enables the counselor to provide relevant and appropriate advice in circumstances where students are considered to be “the main agents” as well as “experts of their own affairs” (p. 396) and yet counselors’ institutional authority coexists. The advisor in the present study also guided the advisor-learner interaction in a somewhat similar manner.

Although the interactional settings mentioned above differ from that of advising sessions, giving appropriate advice to language learners can also require a great deal of interactional work. As will be discussed, it is important that the advice is co-created based on mutual understanding between the two parties. The application of CA to spoken interaction within the field of advising in language learning can illuminate the mechanism by which the advisor and learner achieve or fail to achieve a common understanding of the learner’s situation and needs in order for the advisor to provide appropriate advice. Using CA, the authors aim to uncover how the advisor and learner adjust and maintain their mutual understanding during the advising session.

The Data

The data employed for this study is a language advising session that took place in a language center at a private Japanese university. The session is approximately 70 minutes long. At the time of this study, the advisor, indicated as A in the transcripts, had about 10 years of experience as a full-time advisor and had provided professional development training to new advisors. The learner, indicated as L, is a fourth-year education major at the university. Both participants are native speakers of Japanese, and they speak Japanese for the entire session. The conversation was video-recorded throughout the session and transcribed using the convention developed by Gail Jefferson (see Jefferson, 2004). The descriptions of the convention appear in Appendix B, and abbreviations of the gloss translation are in Appendix C. Arrows in excerpts indicate utterances that are significant to the analysis and accompanied numbers show particular steps in the sequence.

At the beginning of the advising session, the learner explained that she wants to become a primary school teacher, and because English is taught at primary school, she would like to know how to study to improve her English and how to use the language center. Two segments of advice-giving were found in the 70-minute conversation, with one not receiving overt acceptance or rejection (Segment 2) and one receiving acceptance (Segment 4). Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the session with the notable events within each segment.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Advising Session

Confirmation Requests

One of the types of stepwise entry to advice-giving Vehviläinen (2001) identified in her study entails a series of question-answer sequences designed to invite confirmation from students, which could result in either confirmation or new information such as an opinion. Peräkylä and Vehviläinen (2003) have argued that in career guidance sessions, it is important that the counselors demonstrate that their advice is built on the elicited information about the student such as their opinions and preferences. By grounding advice in question-answer sequences, counselors give primacy to students’ perspectives before providing their opinions on a matter. This way they can interact to provide advice based on students’ perspectives to maintain learner-centeredness. Although Vehviläinen’s (2001) study identified this pattern within advice-giving segments, the session examined for this study found similar exchanges earlier within the information seeking segments where the advisor requests the learner’s confirmation on newly obtained information, the practice of which we call confirmation requests.

Early in language advising sessions, the advisor will guide the conversation to elicit information about the learner’s background. This is particularly important because the advisor needs to obtain adequate information to be able to provide support and advice tailored to each learner. This usually includes the learner’s learning goals, learning habits, previous learning experience, current language level, degree of learner autonomy, affective issues, motivation and necessity of learning the language. In the advising session examined in this study, the advisor also attempted to gather this fundamental information to understand the learner’s needs and offer the most suitable educational support at the time. Although the organization of the advising session, that is transitioning from understanding the learner to giving appropriate advice, may sound rather straightforward, each event is carefully managed through small steps. In particular, the advisor in this study presented her understanding of the previous talk and requested confirmation. She used a series of confirmation requests to ensure mutual understanding between the learner and herself.

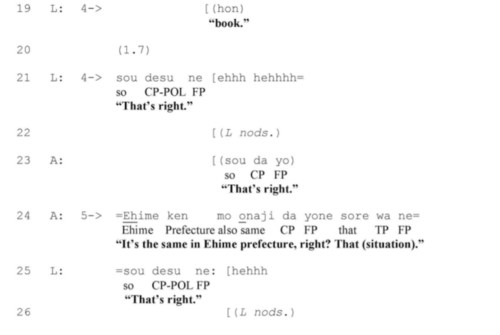

The extract from Excerpt 1 contains an example of a confirmation request found in this study. The exchanges occur in Segment 1 (see Figure 1) after the learner (L) told the advisor (A) that she wants to become a primary school teacher and explains the reason why she came to talk to the advisor, namely she wants to improve her English because foreign language education has been introduced in primary schools. She also revealed that her English is not good and she has taken only required English classes at the university, opting out of an elective class offered to education majors. This information provided, the advisor topicalized the fact discussed previously and requested confirmation: “if (you) are going to teach primary school childre- at a primary school, it’s a fact English is going to be a requirement in the future¿” (Arrow 1).

In response to the advisor’s request, the learner provided confirmation (Arrow 2). Given the previous remarks, that is the learner has not been studying English recently, and the advisor’s response to this with a contradictory starter, “demo” (but), the advisor’s utterance could be taken by the learner as a challenge. However, the learner seems to agree with what has been projected by the advisor’s utterance. This is especially observable from the learner’s verbal and nonverbal language after certain words are produced; “shougakuse[i]” (primary school children) at Line 1, “hissu” (requirement) at Line 6, and “natte iku wake damon ne” (it’s a fact that it’s going to become) at Lines 6 and 9. Having seen an example of how the advisor seeks confirmation, the focus now turns to how confirmation requests such as this one function in subsequent turns.

Confirmation requests and intersubjectivity

Intersubjectivity refers to the interactants’ participation in the co-creation of meaning and understanding during the interaction. The use of confirmation requests can foster understanding between the advisor and learner as they allow the advisor to demonstrate that they are closely listening to the learner and understand their factual representations or mental situation, and move the conversation forward in a stepwise manner. Let us examine the previous interaction again in Excerpt 1.

Notice that after the advisor’s first utterance “English is going to be a requirement in the future¿” (Arrow 1) is accompanied by the learner’s non-verbal agreement (Arrow 2), the advisor rephrases her initial statement to “mou hissu” (it already is a requirement) by initiating the utterance with “to iu ka” (or rather) (Arrow 3). It is only after this restatement is also confirmed by the learner (Arrow 4) that the advisor associates this common circumstance in Japan, namely implementation of English education in primary schools, with the learner’s own situation by checking if it is the same for the prefecture where she wishes to work. It is observable in this excerpt how the advisor mentions a general fact and gradually, through a series of confirmation requests, moves on to the learner’s personal concerns in order to highlight the necessity of studying English.

When considering the delivery, as will be discussed in more detail below, these confirmation requests are effective in the sense that they prevent misunderstanding or mismatching of perceptions, which might consequently hinder the offering of well-informed advice. Unlike casual chats taking place in cafes, the talk in advising sessions has a specific conversational goal as well as time constraints. The talk should move towards its goal, which often is to give informative advice, and in this sense, these confirmation requests help the interaction progress while gaining extra, relevant information and ensuring mutual understanding. When confirmation requests are delivered and responded to, these then allow the conversational participants to deal with additional or more detailed information.

Confirmation requests and interpretations

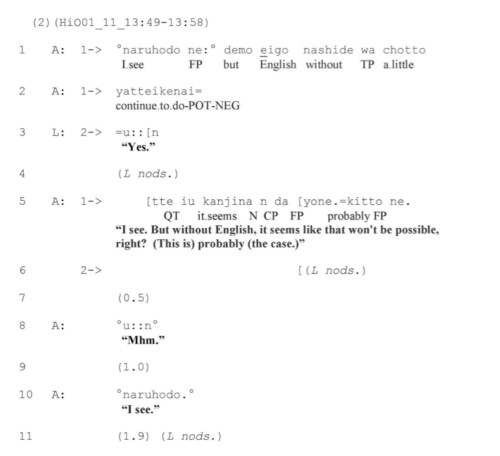

Having gathered some background information from the learner, the advisor in this study sometimes interpreted the given information and checked her understanding with the learner. Peräkylä (2013) has argued that practitioners in psychotherapy “examine the patient’s talk beyond its intended meaning” (p. 552), and interpret the utterances to help the participants to work together to construct “new ways of understanding” (Peräkylä, 2005, p. 163). The advisor’s interpretation observed in this study functioned particularly to highlight or remind the learner of the necessity of learning English, probe the learner’s mental state, and explore the cause of current problems. Excerpt 2, which is taken from Segment 1, shows an example of how interpretation is used. Prior to the excerpt, the advisor asked why the learner wishes to work at a primary school instead of an alternative choice, junior high school. Among other reasons, the learner explained that she enjoyed her teaching training at a primary school, and unlike junior high schools, where a teacher usually teaches one subject, she would be able to enjoy seeing the students learn different subjects. Knowing that primary school teachers have to teach several subjects including English, the advisor interpreted the learner’s situation as somewhat troublesome (Arrow 1).

This utterance of the advisor then functioned to highlight and bring back the important issue on the table, that is it would be impossible to become a primary school teacher without being able to teach English. In so doing, this confirmation request allowed the participants to clarify the necessity for the learner to study English and prepare the ground for the advisor to provide advice later in the session.

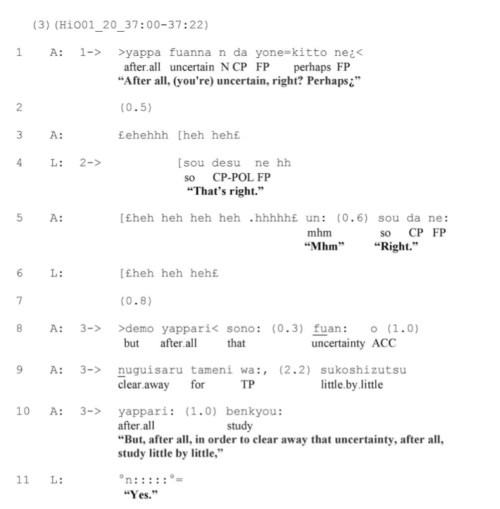

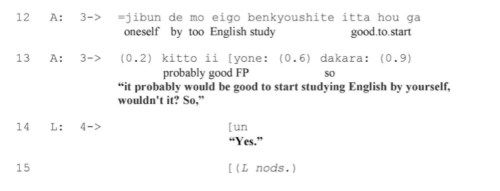

Excerpt 3, extracted from Segment 3, demonstrates a case in which interpretation embedded in a confirmation request functions to raise possible problems. After receiving some advice on her English learning (Segment 2), the learner asked the advisor whether English is going to be important in the future. Having already given two advantageous points of being able to use English relevant to the learner’s situation, the advisor surmised the intention behind the learner’s question and imparted her interpretation, that is the learner is uncertain (Arrow 1).

This utterance then enabled the advisor to elicit the learner’s feelings towards English learning and address the affective issue presented by the learner. Having established the ground for the upcoming advice, the advisor moved on to suggest what the learner should do to eliminate the uncertainty (Arrow 3).

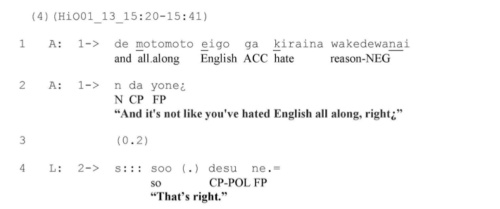

Excerpt 4 shows another case which includes a confirmation request for a proposed interpretation. Prior to the excerpt in Segment 1, the learner explained that she had become more aware of the necessity of learning English during her teaching training when she had discovered the primary school teacher she was working with was not so good at English. Earlier in the session, the learner explained she had enjoyed learning English in primary school but had no longer felt the same way after junior high school. The advisor interpreted this as a positive disposition towards English and attempted to check her understanding, that is the learner did not hate English all along (Arrow 1).

This question received a noticeable pause followed by an affirmative yet rather indecisive answer with some hesitations (Arrow 2). After receiving the halfhearted answer from the learner, the advisor attempted to request confirmation for the second time (Arrow 3). Having received the confirmation in this hesitative manner, the advisor provided an account for her earlier assumption by explaining that it could be the case that the English education the learner had received in the past was oriented for school entrance examinations and this could be the cause of disliking English after primary school (Arrow 5). In so doing, the advisor presented her interpretation of the cause of the learner’s current negative attitude towards English. It was only at this point that the gaps in the participants’ understanding of the learner’s situation started being filled as the advisor’s account received some more affirmative responses (Arrow 6). Unlike the hesitative confirmation after a noticeable pause in Line 4, the learner’s responses at Lines 14, 18, and 23 were followed or accompanied by nonverbal agreement and produced before the completion of the advisor’s utterances.

The use of interpretation then can be said to function to skillfully shift the focus to topicalize what appears important at the time so as to fill the gaps in the participants’ understanding. In particular, as shown with the above excerpts, the advisor was able to highlight the necessity of learning English, shed light on the learner’s affective issue, and probe the source of the current problem.

Confirmation requests and repair

In any kind of talk, whether mundane or institutional, it is impossible to maintain error-free interaction. When facing a problem in speaking, hearing, or understanding, participants in the conversation address the problem (Schegloff, 2007), and this practice, termed repair, is also often observed in cases where speakers adjust the prior segment where no obvious mistakes are involved (Schegloff, Jefferson, & Sacks, 1977). By repairing the “trouble source” or “repairable” (p. 363) in appropriate places, the participants manage to maintain or restore intersubjectivity (Schegloff, 2007). According to Drew (2013), “speakers may change or alter something not because it is factually incorrect, but in order to convey something in a more nuanced or apposite fashion, perhaps with respect to how their turn may be understood, and perhaps also to avoid being (mis)understood in certain ways” (p. 133). Schegloff (2007) has noted cases where questioners repair their own questions when confronting a possible dispreferred response, such as rejection or disagreement, so as to adjust their prior turn to align with the upcoming response.

When checking her understanding during a confirmation process, the advisor also repaired her utterance when the assumption that underlied the confirmation utterance was possibly wrong. Excerpt 5 from Segment 3 illustrates this. After the learner realized that she needed to increase her confidence and the lack of opportunities to speak English was preventing her from doing so, she admitted that she was aware that the situation would improve if she came to the language center to study but she also expressed some uncertainty. Having heard the conflicted thoughts of the learner, the advisor attributed this to an affective issue and asked the learner if she was bashful (Arrow 1).

The question was followed by a relatively long pause (1.6 seconds) which led the advisor to negate her earlier question by asking if that was not the case (indicated with R for repair). This repaired assumption then received an agreement from the learner with exact repetition (Arrow 2), and the learner started to reveal her feelings towards English learning and being in the center where only English is permitted. In the case of a discrepancy in the advisor’s perceptions, the confirmation process creates opportunities to adjust discrepancies before moving on to the next step. This process then allows conversational participants to suspend the ongoing talk and adjust the potential misunderstanding at the relevant local places, ensuring the intersubjectivity between them as the talk progresses.

Discussion

One of the goals of advising in language learning is to provide suitable advice, and in order to do so the advisor has to accurately understand the learner’s situation and needs based on any relevant information the learner provides. The excerpts shown in this study suggest that transitioning from seeking information and understanding the learner to giving advice is underpinned by a series of confirmation requests. Having obtained new information or perspective from the ongoing talk, the advisor closely monitored the learner, presented her understanding, and requested confirmation. Additionally, when facing the possibility of misunderstanding, assumptions underlying the advisor’s confirmation requests were repaired to maintain intersubjectivity.

Advice-giving is not a straightforward undertaking. In the session we observed, the advisor’s first attempt at advice-giving was met by silent rejection, which led the advisor and learner to readjust the course of the interaction. After more talk, the advisor made a second advice-giving attempt, which was successful. As a result of this advice, the learner met with a teacher in the conversation lounge once a week during the semester to practice spoken English on a range of student-selected topics. This might seem quite far from the learner’s initial inquiry about using English in her future career as an elementary school teacher, but the learning plan addressed the learner’s concerns that were revealed and confirmed in the interaction with the advisor. This learning plan was based on personalized advice and was co-authored by the learner, who reflected on her English learning experience, beliefs, and goals with an experienced guide. Our finding suggests that the advisor’s use of confirmation requests helped them to assure mutual understanding and maintain a learner-centered perspective during this session.

A secondary aim of this paper was to contribute a new perspective to the body of knowledge and beliefs about the skills used by advisors. It is undeniable that Kelly’s skills are particularly useful as a framework for helping novice advisors become aware of the types of techniques which can be used during an advising session and for analyzing one’s own reflections as a form of professional development. However, Kelly’s skills cannot provide an explanation for the actual interaction that takes place between the advisor and learner and it is doubtful that this was Kelly’s intent.

What does this new perspective bring? For example, Morrison and Navarro (2012) suggested an additional macro-skill — clarification — which they identified in 6 out of 14 professional development reflections of advisors who were using Kelly’s skills as a framework to analyze one of their own advising sessions. They explain:

This macro-skill could be realised by any or a combination of micro-skills such as paraphrasing, attending, summarising, concluding, restating, or questioning. By interacting to clarify and specify meaning, both the learner and LA [learning advisor] ensure they understand each other. Clarification could be instigated by either participant but it would go some way to ensuring the dialogue progresses in a direction both participants understand.

Our findings support their proposed macro-skill and provide evidence from an emic perspective of what Morrison and Navarro describe based on their analysis of advisors’ reflections. This interactional description together with a description of the technique from the advisor’s perspective could help novice and experienced advisors alike to understand how clarification is achieved. This result illustrates one way in which, as Peräkylä and Vehviläinen (2003) stated, CA can be used to refine practitioners’ understanding of interactions in their field.

Finally, since this is a single study using data from a single session, we are left wondering if the mechanism identified in the sequences here would be found in sessions with other participants, a series of sessions with the same participant, participants who do not share the same first language, or sessions conducted by a different advisor. In fact, one of the strengths of this study, that it uses a session conducted by an experienced advisor, is a weakness as well, as we cannot conclude that the phenomena discussed here is characteristic of all experienced advisors while not characteristic of novice advisors. More studies with different participants will be able to validate our finding in the future.

Conclusion

This study took advantage of the characteristics of CA, which presupposes that the functions an utterance carries can only be determined by observing the consequences of what the utterance actually does in the conversation. In this light, the purpose of potential future research may be to uncover other mechanisms that underpin advisor-learner interactions and determine what implications these mechanisms have on the successful provision of advice. We hope this paper will find a place in advisor training and professional development schemes just as other CA studies have influenced the training of experts in other fields such as Heritage and Maynard’s (2005) contribution to the training of medical students based on authentic interactions between doctors and patients. Despite its limitations, we also hope this example of how CA can contribute to the field of advising in language learning and these unanswered questions will stimulate more research on language learning advising using CA in the future.

Notes on the contributors

Yukari Rutson-Griffiths is a Learning Advisor at Hiroshima Bunkyo Women’s University. She studied conversation analysis for her master’s degree. She has been teaching English for about five years and is interested in dialogues in language advising.

Mathew Porter is an Assistant Professor of English at Fukuoka Jo Gakuin Nursing University. Prior to his return to full-time language teaching, he spent three years working as a learning advisor in a self-access facility. He is currently co-coordinator of the Learner Development Special Interest Group of the Japan Association for Language Teaching.

References

Carson, L. (2012). Conclusion. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 296-299). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Carson, L., & Mynard, J. (2012). Introduction. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 3-25). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Drew, P. (2013). Turn design. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 131-149). Chichester, UK: Blackwell.

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

He, A. W. (1994). Withholding academic advice: Institutional context and discourse practice. Discourse Processes, 18(3), 297-316. doi:10.1080/01638539409544897

Heritage, J., & Maynard, D. W. (2005). Communication in medical care: Interaction between primary care physicians and patients. Cambridge: UK. Cambridge University Press.

Heritage, J., & Sefi, S. (1992). Dilemmas of advice: Aspects of the delivery and reception of advice in interactions between health visitors and first-time mothers. In P. Drew & J. Heritage (Eds.), Talk at work: Interaction in institutional settings (pp. 359-417). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In G. H. Lerner (Ed.), Conversation Analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 13-31). Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2015). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kelly, R. (1996). Language counselling for learner autonomy: The skilled helper in self-access language learning. In R. Pemberton, E. S. L. Li, W. W. F. Or, & H. D. Pierson (Eds.), Taking Control: Autonomy in Language Learning (pp. 93–113). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

McCarthy, T. (2012). Advising-in-action: Exploring the inner dialogue of the learning advisor. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 105-126). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Morrison, B. R., & Navarro, D. (2012). Shifting roles: From language teachers to learning advisors. System 40(3), 349-359. doi:10.1016/j.system.2012.07.004

Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2000). An analysis of the skills and functions of language learning advisers. Links & Letters, 7, 111-126.

Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2012). The skills of counselling in advising: Language as a pedagogic tool. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 43-64). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Mynard, J. (2012). A suggested model for advising in language learning. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 26-40). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Peräkylä, A. (2005). Patients’ responses to interpretations: A dialogue between conversation analysis and psychoanalytic theory. Communication & Medicine, 2(2), 163-176. doi:10.1515/come.2005.2.2.163

Peräkylä, A. (2013). Conversation analysis in psychotherapy. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 551-574). Chichester, UK: Blackwell.

Peräkylä, A., & Vehviläinen, S. (2003). Conversation analysis and the professional stocks of interactional knowledge. Discourse & Society, 14(6), 727-750. doi:10.1177/09579265030146003

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction: A primer in conversation analysis (Vol. 1). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Schegloff, E. A., Jefferson, G., & Sacks, H. (1977). The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language, 53(2), 361-382. doi:10.1353/lan.1977.0041

Seedhouse, P. (2005). Conversation analysis and language learning. Language teaching, 38(4), 165-187. doi:10.1017/S0261444805003010

Stickler, U. (2001). Using counselling skills for advising. In M. Mozzon-McPherson & R. Vismans (Eds.), Beyond language teaching towards language advising (pp. 40-52). London, UK: CILT.

Vehviläinen, S. (2001). Evaluative advice in educational counseling: The use of disagreement in the “stepwise entry” to advice. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 34(3), 371-398. doi:10.1207/S15327973RLSI34-3_4

Wooffitt, R. (2005). Conversation analysis and discourse analysis: A comparative and critical introduction. London, UK: Sage.

Appendices