Mayumi Abe, Temple University Japan Campus,

Satomi Yoshimuta, Seigakuin University, Japan,

Huw Davies, The Open University, UK

Abe, M., Yoshimuta, S., & Davies, H. (2014). “Now maybe I feel like trying”: Engaging learners using a visual tool. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(3), 277-293.

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

For every learning advisor and language teacher, a fundamental goal is to foster learners’ motivation and self-regulation for successful L2 learning. This paper presents a visual tool that can be used in advising and teaching to realize this purpose. With the tool, learners can review their own L2 learning and ability, and create an inventory of their learning strategies, which helps them find their weaknesses, goals and develop their approach.

The tool, the Strategy Tree for Language Learners, consists of the image of a tree, water and the sun. The trunk and leaves of the tree represent learners’ linguistic knowledge and skills, the roots learners’ affective strategies, water cognitive strategies, and the sun sociocultural-interactive strategies. The notions of these three types of strategies are based on the concepts presented by Oxford (2011).

By drawing their own L2 Strategy Tree, learners can perceive their learning situations objectively and notice which step they should take next. In practice at a Japanese university, it was observed that learners developed learning strategies and their motivation increased. The Strategy Tree is a useful tool to encourage learners to feel confident and responsible and help them to self-regulate.

Keywords: language learning, learning strategies, self-regulation, motivation, advising tool

The Strategy Tree for Language Learners was created when the authors met at an academic meeting and shared their experiences from their own learning, advising, and teaching. It did not take long for them to realize and agree that the concepts of the Strategic Self-Regulation (S²R) model of language learning presented in Oxford (2011) could explain some of those cases and also could be utilized in their future practice. Those ideas were soon integrated into one visual image, which finally became the Strategy Tree for Language Learners, which is introduced in this paper.

Self-regulation has attracted teachers’ and researchers’ attention recently in second language education as well as in general education. Although there have been various arguments about definitions about the effectiveness of self-regulation and learning strategies (Gu, 2012; Ranalli, 2012), the Strategic Self-Regulation (S²R) model covering the three important dimensions of language learning, cognitive, affective, and sociocultural-interactive (Oxford, 2011), can be a convenient tool in practice. The Strategy Tree for Language Learners was created drawing on the S²R model with the purpose of applying it as an instructional tool to advising and teaching. Learners need to know what to learn and how to learn to proceed with learning effectively, and the Strategy Tree can help them see the whole picture of language learning, raise their awareness of learning strategies, and consequently develop self-regulation to proceed with their learning autonomously, which were described as metacognitive, meta-affective, and meta-SI (i.e., sociocultural-interactive) strategies in Oxford (2011).

This paper consists of two sections; the description of the Strategy Tree, and an example of the model application in practice. In the first section, we describe the entire image and components of the model. In the second section, we introduce case studies from when one of the authors applied the model in her teaching context at a Japanese university. The Strategy Tree enables learners to reflect on how learning has taken place and on the development of their English proficiency. It also raises awareness about self-regulation and helps to train learners to develop strategies and ultimately become more successful English users. We hope that the Strategy Tree will be helpful for many learners, advisors, and teachers who are engaged in second language education.

Entire Image and Components of the Strategy Tree

The Strategy Tree for Language Learners consists of a trunk, leaves, roots, water, and the sun (see Figure 1). The trunk and leaves represent linguistic knowledge and skills, while the roots, water, and the sun represent learning strategies that foster the growth of the trunk and leaves. For many learners, the ultimate goal of second language learning is to develop the four language skills (the leaves) based on the linguistic knowledge (the trunk), for better communication in the target language. Adopting appropriate learning strategies can accelerate learning, as stable roots, sufficient water, and plentiful sunshine can nurture the sound growth of a tree. In this model, the roots, the water, and the sun represent affective, cognitive, and sociocultural-interactive learning strategies respectively, and all of those strategies help improve linguistic ability. The next section will explain the components of the model in turn.

Figure 1. The Strategy Tree for Language Learners

Trunk and leaves: linguistic knowledge and skills

When using a language, linguistic knowledge is continually accessed and transformed into receptive or productive communication skills in order to communicate with others (Levelt, 1989). In the Strategy Tree, the trunk represents the learner’s linguistic knowledge of pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar, and the leaves represent his/her proficiency in four skills; listening, reading, speaking, and writing. The size of the Tree represents the current level of the learner, and the shape of the Tree varies in accordance to the balance of the learner’s skills. For example, when the learner has a large amount of linguistic knowledge such as vocabulary and grammar but has not practiced enough to use the knowledge in speaking and listening fluently, the trunk is drawn thick but the upper part of the leaves is drawn small. When the learner is proficient in oral communication but not so proficient in written language, the upper part of the leaves (i.e., listening and speaking) is large while the lower side (i.e., reading and writing) is small. Oral skills are intentionally situated at the top while written skills are at the bottom In addition, receptive skills are on the left while productive skills are on the right expecting that learners can see the relationships between the skills easily. In order to improve proficiency in the target language in a balanced way, or to discover learner needs, it is helpful for the learner to consider which part of the Tree requires focus, and any methods that will encourage the area to bloom.

Figure 2. A Tree drawn by one of Davies’ elementary students, with arrows showing desired areas to be improved.

One of the authors has used the image of the trunk and leaves in her face-to-face language learning advising sessions with various Japanese learners of English for many years, aiming to have learners overview their own linguistic ability and help them make a learning plan. The whole picture of the Strategy Tree was developed from this.

Roots: Affective strategies

Many studies have shown that affective factors greatly influence the effectiveness of learning. Oxford (2011), also emphasizing the importance of the role of affect, presented two affective learning strategies; “Activating Supportive Emotions, Beliefs, and Attitudes” and “Generating and Maintaining Motivation”. The first affective strategy forms the fundamental base of the learners’ mind. These factors have a powerful influence on learners’ overall learning, and can be modified by educational intervention as well (e.g., Yeager & Dweck, 2012). For the second affective strategy regarding motivation, it is crucial to understand that motivation is dynamic and changes through the course of learning (see Heckhausen & Gollwitzer (1987) for the Rubicon model of action phases, and see Dörnyei & Ottö (1998) for a process model of L2 motivation) so that both generating initial motivation and maintaining the motivation are equally of great significance. Because the affective dimension is the basis of human behaviors including language learning, it is situated as the “roots” of the Strategy Tree. Reflecting on their own affective situations, learners can improve their meta-affective strategies which manage affective learning strategies (Oxford, 2011).

Water: Cognitive strategies

Oxford (2011) explained cognition as “the mental process or faculty of knowing, including aspects such as awareness, perception, reasoning, and certain kinds of judgments” (p. 46). Drawing on theories such as schema theory, information-processing theory, activity theory, and cognitive load theory, she proposed six cognitive strategies; “Using the Senses to Understand and Remember,” “Activating Knowledge,” Reasoning,” “Conceptualizing with Details,” “Conceptualizing Broadly,” and “Going Beyond the Immediate Data”. In second language acquisition, learners should notice linguistic information, intake it, integrate it to their schemata (Gass & Selinker, 2008), and automatize it by practice (Dekeyser, 1996). Acquisition is also the process of placing new information in the limited capacity of working memory, and then transferring it to the storage of long-term memory as a part of their interlanguage. Those six cognitive learning strategies can facilitate the smooth operation of such a complex process, and make learning more effective and efficient. In this model, they are situated as “water” because it facilitates the growth of the tree. The idea of the water could help the learners think about what strategies are best to accelerate their learning, which would lead to promotion of their metacognitive strategies (Oxford, 2011).

Sun: Sociocultural-interactive strategies

As sociocultural-interactive strategies, Oxford (2011) presented the following three strategies; “Interacting to Learn and Communicate,” “Overcoming Knowledge Gaps in Communicating,” and “Dealing with Sociocultural Contexts and Identities”. The first strategy is based on the pedagogical implication that linguistic knowledge and skills should be learnt through meaningful communicative activities (e.g., Ellis, 2005). Oxford also refers to Vygotskyian approaches, stating that learning occurs through interaction with others in sociocultural contexts. The second strategy refers to communication strategies such as paraphrasing, borrowing, and avoidance (Dörnyei & Scott, 1997). Because learners encounter numerous communication gaps and breakdowns in the process of building their interlanguage, the ability to use communication strategies is necessary both to maintain the ongoing conversation and as the result, to keep learning through interaction. The last strategy concerns the learners’ accommodation with the background culture of the target language, which includes both understanding and acculturating the culture, and negotiating their identities when experiencing “the unequal relations of power” (Oxford, 2011, p. 94) in the community. Those sociocultural-interactive learning strategies are situated as the sun in the Strategy Tree, because they shed light on the whole tree and greatly promote the growth of the leaves (i.e., four skills). Seeing how the sun affects the growth of the tree, learners would realize the importance of sociocultural-interactive strategies, which would lead to the improvement of the meta-SI strategies which can manage the learners’ sociocultural-interactive strategies (Oxford, 2011).

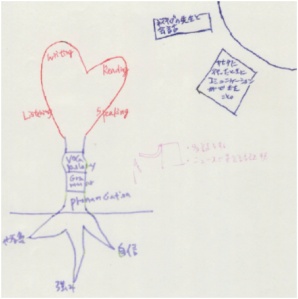

Simplified version of the model for learners

The primary purpose of the model is to use it as a tool in order to have learners reflect on their language learning and foster their self-regulation. For this purpose, the model should be easy enough for them to understand. Although we cited the expressions representing the strategies directly from Oxford (2011) in our original model (see Figure 1), those expressions might be a little difficult for learners who are not familiar with the concepts. Therefore, we recommend to create a simpler version for learners using easier words (see Figure 2), which can be used in advising sessions and/or classroom teaching and directly shown to the learners, as introduced in the sections below. Learners can draw their own original picture referring to the model, or draw on a template on which only the terms are prewritten (see Figure 3). Through this activity, learners can reflect on their current situations and be aware of the possibility of using a variety of learning strategies. The Strategy Tree can help both advisors/teachers and learners see the whole picture of language learning and make a better-balanced learning plan which also suits individual learners’ needs.

Figure 3. A Simplified Version of the Strategy Tree

Figure 4: A Template of the Strategy Tree

Utilization of the Strategy Tree

Although the Strategy Tree discussed earlier was originally developed for the purpose of face-to-face advising so that learning plans and materials might be individually customized, it might be beneficial in any situation to raise awareness and excite the motivation of an individual learner. It was also utilized as an attempt to enhance learner motivation in some English classrooms of a Japanese university, where students have varying levels of motivation. That means the Strategy Tree was introduced in a way different from in an advising session.

Learner profile

The target learners study at a university in Greater Tokyo, which one of the authors is working at. Their majors include European-American culture, child studies, human welfare, local community policy, political science and economics, and Japanese culture. The majority of the students were aged from 18 to 22, but there were a few adult students. In terms of nationality, ten percent of the student population was of international background, mainly from other Asian countries. The English proficiency level varied. The top layer ranked at the pre-first level of STEP test so they were intermediate, and the bottom layer was at the fourth or fifth level and were beginner learners of English. Their proficiency level had been checked by a placement test before the semester started and they had been subsequently placed into English classes.

How the Strategy Tree was used

Three stages were followed when using the tree in university classes.

Step 1: Consciousness raising questionnaire

On the first day of the semester, handouts (Appendix A and B) were distributed to the learners. Appendix A, “Consciousness Raising Activity: English Tree”, contains a set of questions that helped learners to reflect on their current English proficiency from each aspect of the three dimensions that Oxford (2011) suggested. Students were free to use the Japanese version as well depending on their proficiency. Learners individually reflected on each component and dimension of their English proficiency and English learning by answering the questions on the handout as preparation to draw the Strategy Tree. Students were reminded that the results of objective evaluations that they had received need not be used in this self-analysis. Although their needs were subconsciously affected by any experiences related to learning English, including test scores, what they perceived as being English learning, and what they realized they needed to work on, it was intended that their analysis was rooted solely in their interests to foster sustainable learner autonomy through Strategy Tree use.

Step 2: Drawing the Strategy Tree

Following the pre-questionnaire, the learner produced his/her own Trees, using a sample (see Figure 5) as a guide for expressing each component and dimension according to the development level that they recognized. Learners were encouraged to write down additional information under each heading. After drawing, the learners explained their Strategy Trees to peers, the teacher, and the class.

Figure 5. Sample Strategy Tree

Step 3: Post-questionnaire

Finally, the post questionnaire (Appendix B) was provided for the learners to jot down and clarify what they felt about language learning in the whole process of reflecting on themselves and drawing and sharing the Trees. The learners were encouraged to describe whatever comments, feelings, ideas and learning strategies they come up with during the activity. It was discovered that in completing the post-questionnaire, they realized they had drawn the Strategy Trees with absorbed interest and they received new findings about their attitudes in learning English as shown in their feedback on the post questionnaires (see examples below).

Examples

Two representations of the Strategy Tree and comments from other students will be discussed in this section.

Case Study 1

One of the target representations was made by a Japanese female student, Hanako (a pseudonym). Her English proficiency ranked at the intermediate level. She had passed the pre-first grade of STEP Test and she was one of the successful learners. Despite her high proficiency in English, she seemed to have low self-esteem.

In her pre-questionnaire, she evaluated her reading, writing, and vocabulary as level two and listening, speaking, grammar, and pronunciation as level one. Thus her Strategy Tree seemed top-heavy and off balance because she recognized her listening and speaking areas were less developed.

Figure 6. Hanako’s English Tree

It was observed that this participant, Hanako, had a good command of the tools available for intermediate learners. For “water,” which accelerated language learning, she noted two learning tips that she had used and recognized to be effective, extensive reading and language programs on NHK (or a Japanese national TV channel, also known as Japan Broadcasting Corporation, which broadcasts a variety of language programs). She watched a particular program focusing on English news targeting at intermediate learners. Learning English through news was challenging for most of the students and was not mentioned in others’ Trees. Hanako, who was a successful learner, seemed to be able to choose from a variety of learning tips at different levels.

In the post-questionnaire, she commented that drawing the Tree motivated her slightly. Although this comment did not seem positive, since she was shy and her self-esteem was comparatively low, this meant that there was some improvement in her motivation. She wanted to make all four skills the target area from now on but she would like to place an emphasis on speaking. In her comment, she realized that there were so many other things that she could and should do to develop her language skills and she “wanted to continue learning English using exams as an indication of her development without falling into idleness halfway.” It was observed that the Tree helped her grasp a holistic view of her language abilities and also that she built better awareness to learn English at the starting point of the semester.

Case Study 2

Taro (a pseudonym) had beginner-level English proficiency, and it did not seem that he had been academically successful in learning English. His mindset appeared to be presented in this faint rendering of his Strategy Tree.

Figure 7. Taro’s Strategy Tree

In the pre-questionnaire, he rated all the components of his linguistic skills and knowledge at level one except for vocabulary, which was rated level two. He stated that he did not have a particularly strong motivation. He did not use English in his social life (the Sun). He claimed to use no learning techniques (Water). His Tree looked like a matchstick with a few fibrous roots under the ground.

In the post-questionnaire, however, Taro confessed that hitherto he had never reflected on his language learning and found that this activity elevated his motivation moderately. From then on, he hoped to develop the skills with more emphasis on vocabulary because he realized that he was better in vocabulary that any other skill. He commented, “I knew that I was vaguely aware that I did not have English skills, but I realize that I have not tried to study English. Now maybe I feel like trying.” This attitude revealed that he became inspired through the process of drawing his Strategy Tree.

Comments from other students

In addition to these two examples, there were noticeable changes occurring during the process of reflecting on English learning among approximately thirty students who drew the Strategy Trees. Generally the students began understanding the use of the Strategy Tree while they were drawing and it seemed that they enjoyed this activity and found it highly worthwhile. According to the questionnaire implemented after drawing the Trees, the majority of the learners presented favorable comments, some of which are presented below;

- I wasn’t sure if I could keep up in class but now I know I have to pull myself together.

- Now I’d like to talk with a foreigner. I want to express my own opinion, share laughter, and sing together at a karaoke.

- I realize grammar is my weakness. So I’d like to use FOREST (a grammar drill) to overcome. I want to be able to speak English. I’m going to use English on a daily basis.

- While I was drawing the Tree, I realized myself I wanted to learn English skills so that I could study abroad. But I’m not confident enough. I’d like to have confidence in learning English.

- From now on I want to learn skills of all different components and dimensions. Now I know I’m highly motivated though I don’t know what to do and how to do.

As the learner above reflected that ‘From now on I want to learn skills of all different components and dimensions’; for language advisors and teachers, it is important that use of the Strategy Tree is followed up with strategy training on multidimensional perspectives and ongoing support. It was noticeable that the whole process increased the potential for developing self-regulation, and it was also essential that learners were made aware of how they could improve their learning practices. Drawing a Strategy Tree contributed to learners’ visually perceivable development of language skills and metacognitive skills. It could urge learners to reflect on their learning status, progress and goals. Therefore the Strategy Tree in a birds-eye view was successful in refreshing and uncovering learners’ motivation from the angles unnoticed heretofore.

Conclusion

The Strategy Tree is a practical visual tool, which helps students to set learning goals and harnesses critical self-reflection. It can give students a voice, and facilitate student-advisor or student-teacher interaction when advising (Yamaguchi et al., 2012). This makes students partners in the learning process, ensuring learning programs fit individual learner needs (Clark, 2012). By helping students visualize the whole picture of their learning, the Strategy Tree raises learner awareness of possible strategies that may help them achieve their goals and might increase their motivation as well.

It is believed that using a wider range of strategies leads to greater proficiency (Yamaguchi et al., 2012), and therefore, any tool that can encourage students to broaden their language learning strategy use is beneficial to language learning advisors and teachers. Although this paper introduced only one example of the model application, a variety of other ways of application can be considered. We hope that the Strategy Tree might become a handy tool for all advisors and teachers who hope to foster learners’ meta-strategies and self-regulation, which consequently could lead to their more successful language learning.

Notes on the contributors

Mayumi Abe is currently a language learning advisor and a lecturer at universities in Japan. She has experience of advising and teaching a variety of Japanese learners of English. She holds an M.S.Ed. in TESOL from Temple University (Japan). Her research interests include learner autonomy, self-regulation, learning strategy and language testing.

Satomi Yoshimuta teaches as a part-time lecturer at Seigakuin University in Japan. She holds an M.A. in Literature from Aoyama Gakuin University (Japan) and a M.S.Ed in TESOL from Temple University (Japan). Her research interests are in learning strategy, learner autonomy, cooperative learning and extensive reading.

Huw Davies is senior teacher at a language school in eastern Tokyo. He has experience teaching English in New Zealand and Japan. He is currently a graduate student at the Open University. His research interests include new literacies, including podcasting, and learner identity, silence and autonomy.

References

Clark, I. (2012). Formative assessment: Assessment is for self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 24, 205-209. doi:10.1007/s10648-011-9191-6

DeKeyser, R. (1996). Exploring automatization processes. TESOL Quarterly, 30(2), 349-357. doi:10.2307/3588151

Dörnyei, Z., & Ottö, I. (1998). Motivation in action: A process model of L2 motivation. Working papers in Applied Linguistics, 4, 43-69.

Dörnyei, Z., & M. Scott. (1997). Communication strategies in a second language: Definitions and taxonomies. Language Learning, 47, 173-210.

Ellis, R. (2005). Principles of instructed language learning. System, 33(2), 209-224. doi:10.1016/j.system.2004.12.006

Gass, S., & Selinker, L. (2008). Second language acquisition (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Gu, Y. (2012). Learning strategies: Prototypical core and dimensions of variation. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(4), 330-356. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/dec12/gu/

Heckhausen, H., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (1987). Thought contents and cognitive functioning in motivational versus volitional states of mind. Motivation and Emotion, 11, 101-120.

Levelt, W. (1989). Speaking: From intention to articulation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Oxford, R, L. (2011). Teaching and researching language learning strategies. Edinburgh, UK: Pearson Education.

Ranalli, J. (2012). Alternative models of self-regulation and implications for L2 strategy research. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(4), 357-376. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/dec12/ranalli/

Yamaguchi, A., Hasegawa, Y., Kato, S., Lammons, E., McCarthy, T., Morrison, B.R., Mynard, J., Navarro, D., Takahashi, K., & Thornton, K. (2012). Creative tools that facilitate the advising process. In C. Ludwig, & J. Mynard (Eds.), Autonomy in Language Learning: Advising in Action (pp. 115-136). Canterbury, UK: IATEFL.

Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302-314. doi:10.1080/00461520.2012.722805.

Appendices – see PDF version