Eduardo Castro, Federal University of Pará, Soure, Brazil

Castro, E. (2019). Motivational dynamics in language advising sessions: A case study. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 10(1), 5-20. https://doi.org/10.37237/100102

Abstract

Researchers have increasingly been interested in the complex and dynamic character of motivation. Recent studies point out the complex fluctuation of motivation in a situated perspective, as in a language classroom. However, little is known on how motivation evolves in out-of-class contexts, as in advising in language learning context. The present paper aims to explore the dynamics of motivation to learn English of an advisee. Data of this longitudinal case study were collected through a motivational grid combined with advisor’s diaries and an in-depth interview, which were analyzed following the interpretative phenomenological analysis procedures. Results revealed that task complexity, tiredness, sense of competence, teachers and peers contributed to the fluctuation of the participant’s motivation.

Keywords: motivation, advising in language learning, foreign language learning, learning trajectories, complex adaptive systems.

The language learning trajectory towards language proficiency is a personal, long and tortuous journey which is influenced by several factors, including learner motivation. In fact, motivation has been described as having a fundamental role in providing the necessary energy for one’s pursuit of the goal of proficiency and engagement in such a process (Dörnyei, 2005; Ushioda, 2011). The focus on understanding the processual development of motivation has emerged from the interest of researchers in learners’ behaviors in a situated perspective (Dörnyei & Ryan, 2015). More recently, such interest takes into account a complexity-informed frame, as motivation is no longer seen as a static, isolated individual difference, but as a construct that evolves on different timescales and in response to internal and external influences to the learner (Dörnyei, MacIntyre, & Henry, 2015; Waninge, Dörnyei, & De Bot, 2014).

Despite the increasing number of publications that investigate learner motivation from a complexity-informed perspective (Boo, Dörnyei, & Ryan, 2015), few of them have considered it within the context of advising in language learning. Advising in language learning is defined as “a process of helping someone to become an effective, aware, and reflective language learner” (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 1), which entails a holistic view of the language learner. Castro and Magno e Silva (2016), for example, investigated how language advising contributed to the participant’s motivation in different language learning contexts. By taking into account six lenses on the same learning process, the authors highlighted how the participant’s interaction with her advisor was of paramount importance for her motivation regulation in different learning environments. If language advising was particularly helpful for that learner, how it helps learners to regulate their motivation without the support of an advisor was the question posed at that time. As an answer to that question, Castro (2018) conducted a longitudinal case study to explore how language advising influenced the participant’s middle term motivation. The study concluded that language advising was one of the sites where positive language learning experiences took place, which led to the strengthening of the participant’s ideal self both as a learner and a teacher.

Different from the aforementioned research studies, the present article turns its attention to a third gap in researching motivation in advising in language learning, as it explores how motivation fluctuates within and between advising sessions. More specifically, the current paper aims to identify and describe the factors that contribute to the waxing and waning of the level of motivation of one single advisee over time. In this regard, by adopting a complexity-informed perspective, the study combines a motivational grid along with an advisor’s diaries and an in-depth interview with the learner. By understanding motivation as an emergent property from the learner’s interaction with the advisor, this study may clarify some local practices of advising.

The Complexity Perspective in Applied Linguistics

In a brief look at the field of Applied Linguistics, what becomes clear is the increasing interest of researchers in adopting a complexity-informed approach in order to explain language learning and teaching phenomena as complex dynamic systems. In fact, since the publication of Diane Larsen-Freeman’s seminal article (1997) two decades ago, for example, some international refereed journals have dedicated special issues to the theme, several books have been published (e.g., King, 2016; Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008; Magno e Silva & Borges, 2016; Ortega & Han, 2017; Paiva & Nascimento, 2011; Verspoor, de Bot, & Lowie, 2011), as well as several articles, book chapters, theses and dissertations, related to different research agendas in the field (cf. Larsen-Freeman, 2017).

This growing interest places Applied Linguistics in the recent complexity turn, which is characterized by the interest in non-linear processes viewed in a holistic approach and in interaction with a range of contextual factors (Dörnyei et al., 2015; Mercer, 2013). Hiver and Al-Hoorie (2016) argue that complexity is not only a productive metaphor to explain language phenomena, but it is an empirical way of seeing reality which, according to Larsen-Freeman (2012), challenges us to understand such phenomena in terms of their complexity and dynamism. In this regard, Larsen-freeman (2013; 2015) and Hiver and Al-Hoorie (2016) understand the complexity perspective as a meta-theory, that is, as a set of coherent principles of reality (i.e., ontological ideas) and principles of knowing (i.e., epistemological ideas) that, for applied linguists, underpin and contextualize object theories (i.e., of language and language development) consistent with these principles (de Bot et al., 2013). (Hiver & Al-Hoorie, 2016, p. 2).

These principles refer to the characteristics of complex dynamic systems (CDS henceforth): openness, complexity, nonlinearity, self-organization, adaptation, emergence, and context-dependency, which will be briefly described in the following paragraphs.

CDS are formed by two or more interrelated components that interact over time (Dörnyei, 2014; Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008). Each component can be a nested complex system by itself (Mercer, 2016). One of the major characteristics of CDS is their dynamism, as they are in continuous change (De Bot, Lowie, & Verspoor, 2007; Larsen-Freeman, 2015). This change can be smooth or abrupt and also nonlinear, as the effect is not always proportionate to the cause. The dynamism of CDS is due to their openness to external influences. As systems are in a constant flux and adapt to these influences, they are also adaptive. Another feature of CDS is their chaotic nature once unpredictable changes may occur; that is, a small change may have a significant impact on systems development. This development occurs in a state-space, i.e., a metaphorical area that represents all the possible states, positions or outcomes of a system (Hiver, 2015; Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008). In this spatial metaphor, there are certain states, modes or patterns of preferred behaviors of the systems called attractors (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008; Mercer, 2013). They “are critical outcomes that a system evolves toward or approaches over time” (Hiver, 2015, p. 21). In other words, attractors are recurring patterns of behavior of a given system.

Emergence is a fundamental feature of CDS. It refers to the result of the interaction between different elements and agents of a system (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008) that “cannot be deduced from an understanding of the individual components” (Mercer, 2013, p. 378). Davis and Sumara (2006) state that the components of CDS are in interaction in/with a context. Similarly, Mercer (2013) argues that contexts are an integral part of the system, rather than an external variable affecting it from outside. In fact, contextual factors influence the trajectory of the system by fostering or constraining changes in its development in the state-space (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008). However, it is not the presence of these factors that influences language teaching and learning, but rather the way in which the agents of the system perceive and relate to them (Larsen-Freeman, 2016; Mercer, 2016). The boundaries of systems are blurred because of their interconnection with a range of other components. Due to the interconnection of components, the question of how to research a complex system has been a hot topic for discussion in the literature. In this regard, Larsen-Freeman (2012) emphasizes the need to select and define a focal point, a system, according to the research purpose. In this article, I consider language advising as a CDS and motivation as an emerging property from the learner-advisor interaction, recognizing its interconnection with other subsystems.

Language Advising from the Complexity Perspective

Advising in language learning, or language advising, is a relatively new field in applied linguistics that has been attracting attention due to its focus on individual language learning trajectories (Castro, 2018; Kato & Mynard, 2016; Magno e Silva & Borges, 2016; Mozzon-McPherson & Vismans, 2001; Mynard & Carson, 2012). It aims to help learners to become more aware, reflective, and effective regarding their language learning, so they can become more autonomous, motivated and self-regulated learners (Ciekanski, 2007; Kato & Mynard, 2016; Mozzon-McPherson, 2007). Through the advising process, the learner is encouraged to be an active agent, a protagonist in charge of choosing, constructing and evaluating learning plans with the support of a language advisor, a person who facilitates one’s learning process, rather than directs it (Mynard, 2012).

Mynard (2012) describes language advising from the perspectives of constructivism and sociocultural theory and understands the advisor as a mediator of learning. In this vein, the author proposed the well-known model of advising that consists of dialogue, tools and context. In a complexity perspective, the advisor is seen as another agent in the learner’s language learning system that disturbs and energizes their trajectories, helping them to find their own voice (Castro & Magno e Silva, 2016; Magno e Silva, Matos, & Rabelo, 2015). It is important to note that perturbation refers to “events that affect periods of stability in the development of the system” (Henry, 2015, p. 316).

The process of helping someone to become a competent and reflective language learner involves considering a conglomeration of factors related to their life, experiences, beliefs, motivations, identities, among others, that should be considered within a holistic view of the learning process. In this sense, language advising benefits from the principles of the complexity perspective, since by extending the scope of analysis to a dynamic, complex and non-linear trajectory, it considers the potential agents and contexts that may foster or constrain the evolution of that language learning system. Recently, I have argued that language advising could be understood as a CDS in which various components, including the learner and the advisor, are complex systems (Castro, 2018). They interact over time with a multitude of other elements, agents and contexts, such as self-access centers, language classroom, mother tongue and foreign language, learning materials, language teachers, classmates, family, etc. These components also refer to the properties of the temporal and physical environment, such as where the advising session takes place (i.e., self-access center, classroom, or virtual environment), temperature, day of the week, time of the meeting, the interval from one session to another, among other factors that can influence the dynamics of advising.

In my understanding, language advising is an open system since it can be affected by a range of factors that go beyond the advising session itself. In this sense, the student and the advisor are constantly influencing each other in a process of coadaptation. The goals, strategies, and learning plans established by them are constantly (re)evaluated in each advising session so that new ones can be negotiated. However, the effort undertaken by the learner will not always result in the expected outcome due to the nonlinearity of language learning. In the relationship between student and advisor in a particular context, new properties emerge, which can be reflected in a network of environments, including the language classroom (Castro & Magno e Silva, 2016). Among them is motivation, in which language advising has a pertinent role in all its phases. This is because the advisor helps the learner to establish, put into action and evaluate the results of a learning plan.

In the complexity perspective, the motivation to learn a foreign language integrates multiple factors related to the learner, the tasks and the learning environment in a single complex system so that the result of this interaction can be understood as the regulator of learning (Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2011). In the present article, I adopt the person-in-context relational view of motivation proposed by Ushioda (2009). This view places emphasis on the agency of language learners, who are seen as individuals situated in a particular historical and cultural context so that their motivation and identity shape and are shaped by the context (Waninge et al., 2014). This means that motivation is a phenomenon that emerges from the individual and context. Ushioda (2009; 2011) still emphasizes the multiple identities of the individual who, in addition of being a language learner, is also a graduate student, member of a religious community, among other identities that influence his/her motivational process.

The Study

Learner motivation research has increasingly focused on its qualitative character. Yet, Ushioda (2016), one of the advocates of such an approach to motivation research, states that “fewer studies of L2 motivation have been grounded in specific local contexts of practice, focusing on the needs and experiences of particular learners” (p. 566). Although the author refers particularly to the language classroom, this seems to be also true for language advising research, in which there are few studies that explore language learning motivational trajectories, especially if conducted by the language advisors themselves. One of the methods that may illustrate motivation from such a perspective is the longitudinal case study, which is grounded in rich, detailed, personal and contextualized data collected in different intervals of time (Duff, 2008; Yin, 2003). This method is of great value for the language advising context, once this practice focuses on the development of individual and personal language learning trajectories. In this vein, the research questions of the present study are twofold as follows: (a) how does motivation for learning English fluctuate within and between language advising sessions? (b) what are the factors that contribute to such fluctuation, as self-reported by the participant?

Language advising is sensitive to the context in which it occurs so that its definition and practice are constantly negotiated between the learner and the community of advisors. This means that there are different forms of advising conducted around the world with their particular goals and approaches. For example, some places may take a more directive approach, may privilege face-to-face meetings rather than virtual ones, or may even focus on a specific linguistic ability only, such as written production (Mynard & Carson, 2012; Tassinari, 2016). The language advising conducted in the self-access center of Federal University of Pará (UFPA) adopts an indirect approach, prefers face-to-face meetings, although virtual meetings may happen according to the preference of the learner, and focuses on the skills that the student would like to improve (Magno e Silva & Castro, 2018). It is an optional service offered to undergraduate students in German, Spanish, French, English or Brazilian Sign Language and consists of individual meetings between a learner and advisor; each session lasts between 20 and 45 minutes and can be conducted in Portuguese or in a foreign language, depending on the learner’s preference and linguistic competence. It is important to note that advisor is assigned to assist a specific learner and, since there is no limit of sessions offered to the student, the learner can attend as many sessions as necessary with the same advisor.

This case study was conducted with a single participant, advised by the author. Laura (pseudonym) is a 23-year old first-year student of Teaching English as Foreign Language Program. She decided to major in English because she liked the language and saw it as an opening to other courses, such as journalism. Although she has studied English for a few years at a private language school, Laura considers herself a beginner. She decided to participate in the language advising service to find support to help her to organize her studies, to improve her speaking skill and also to regulate her emotions, such as anxiety and lack of motivation. Laura attended eight advising sessions between March and June 2017.

Data were collected through three instruments. The first was a motivational grid that was used to help Laura reflect on her motivation. This instrument measures the level of a learner’s interest and motivation in an immediate learning situation (Pawlak, 2012; Waninge et al., 2014) or retrospectively (Henry, 2015). It consists of a table with two axes: a vertical one that represents the level of motivation and interest measured in terms of ‘high’, ‘partly high’, ‘partly low’, and ‘low’; and a horizontal one that represents the temporal factor. Laura was asked by the advisor to note down in a scale from 1 to 4 how she perceived the level of her own motivation at the moment of advising, “1” meaning the lowest level whereas “4” meaning the highest. This was done twice per advising session, one at the beginning and the other at the end (Figure 1). After noting down the level of her motivation, Laura was asked to provide a brief explanation of the reasons why she perceived that level. Prior to language advising, she had attended a course on how to learn a foreign language which included learner motivation in its syllabus. Because of that, Laura had an idea about the definition of learner motivation, which occasionally led her to turn to advising for help due to her self-reported “lack of motivation”. This previous knowledge helped her to note down her self-perceived level of motivation.

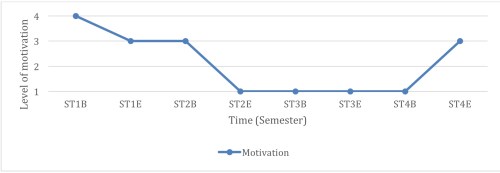

The second instrument was the advisor’s diary in which activities, objectives, learning plans, advising procedures and reflections, and any relevant aspects discussed with Laura were noted down. This instrument helps the advisor to better comprehend the learning process of the learner. The diary entries were written during and after advising sessions and they were shared with the learner. The final instrument was a semi-structured interview conducted one year after Laura was advised. The interview lasted one and a half hours and focused on her learning experience before, during and after the advising sessions. Laura was also asked to plot her motivation on a graph in order to describe her self-perceived level of motivation in each academic semester (Figure 2).

Data were analyzed following the principles of Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA henceforth) as suggested by Henry (2015) and Smith and Osborn (2003). IPA aims to “to explore in detail how participants are making sense of their personal and social world” (Smith & Osbourne, 2003, p. 53). In other words, it focuses on one’s experiences and perceptions of those experiences. IPA uses an interpretative approach referred to as double hermeneutic, which involves two stages called empathic hermeneutics and questioning hermeneutics. This means that while “the participants are trying to make sense of their world [empathic hermeneutics]; the researcher is trying to make sense of the participants trying to make sense of their world [questioning hermeneutics]” (Smith & Osbourne, 2003, p. 53). As language advising is a dialogical reflexive practice, such an approach seems appropriate in order to comprehend the meaning-making process between the learner and advisor.

Findings

Laura’s learning trajectory within a language advising setting

Verspoor (2015) defines initial conditions “as the conditions subsystems are in when the researcher starts measuring” (p. 46). This means that the attractor state that Laura’s motivational system occupies at the beginning of her advising process must be first identified. At the first advising session, Laura mentions that she decided to study English because of a personal interest in the language and the desire to travel to and study in English-speaking countries. She imagines herself as a fluent speaker living in different cities and being able to interact in different contexts. This image of herself as a competent learner can be understood as an attractor state in her language learning, as it shows relative stability in her motivational system (Dörnyei & Ryan, 2015). It is interesting to note that despite having a vivid image of herself as a user (Dörnyei, 2009), Laura has no immediate interest in becoming a teacher of that language, similar to the participant described in Castro’s study (2018). In addition to her future vision, Laura has also a clear idea of what constitutes advising when she reports that it is not a private class, but a support to help her in becoming more aware of her language learning. This clear idea about advising and the advisor’s role facilitates such intervention, while a misconception of what this practice entails may prevent the student from benefiting from that support (Kato & Mynard, 2016).

Figure 1. Motivational Graph Describing the Self-perceived Evolution of the Level of Laura’s Motivation in Language Advising Sessions.

As described before, one of the fundamental characteristics of a CDS is that they are in a continuous state of flux, even in periods of stability (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008). Such a characteristic may also be perceived in terms of motivation, which undergoes changes on different timescales. In this case, motivation may change from one session to another or even in the same session itself due to a constellation of factors internal and external to the individual. Taking a brief look at Figure 1 above, the fluctuation of Laura’s motivation evolving in a complex way because of several factors becomes apparent. In some sessions, her motivation remains at a similar level (S1, S3 and S7), whereas in others it increases (S2, S4, S5 and S6) or even decreases (S7). MacIntyre (2012), cited in Henry (2015), argues that motivation fluctuation depends on the task in which students are engaged, how difficult it is, what happens before the task and also the student’s mood, among other factors. This seems to be the case of Laura, who mentions similar factors by stating that her motivation decreased because of tiredness, task complexity and also how worried she was about grades. On the other hand, an upward movement is noted when she perceives herself as a competent learner or when she observes a slight progress in her learning, as can be seen in the following extract from the advisor’s diary:

(1) We discussed about her agenda. She said it was very difficult to organize her agenda because of her time. At the end, she said her motivation was ‘high’, stating ‘I can do more than I am aware of’. (Advisor’s diary, 12/4/17).

Learners’ motivated behavior is not always perceived by them when they put in effort to perform a given activity. This is true for Laura who, even after completing the tasks and achieving some of her learning goals set in advising sessions (e.g., participating in a conversation group, reading books in the target language and writing a summary about a movie in that language), still sees herself as demotivated. This is a clear example of non-linearity, since engaging in meaningful activities does not guarantee a high level of motivation. It is the way that she perceives her internal and external context that determines her motivated behavior, according to her own beliefs, as we can note in the excerpt below:

(2) Even though she was complying with several activities, Laura mentioned that her motivation was partly low. She emphasized one struggling aspect of her learning (a subject) and described all the tasks and goals as they were not important anymore. I said that she was making a significant progress that should be celebrated. (Advisor’s diary, 26/5/17).

(3) Laura said she would like “to give up” whenever she faces a more complex task or whenever she feels demotivated, but she is now adopting a new attitude. She said, ‘every time my motivation is low I think of you and I know this will pass’. It seems like our discussion about seeing the good side of things and understanding both learning and motivation as a process is having a positive effect on her perception about her learning (7/6/17).

In the excerpts above, the advisor acted as a disturbing agent in the student’s motivational system, causing such a system to move in the space-state to an attractor of a more positive perception of her language learning. This attitude emerges from the learner’s interaction with the advisor.

The advising context is situated in a network of systems that, interconnected, supports students’ learning. One influences the other in a complex, non-linear and adaptive process. Many of the factors mentioned by Laura regarding their influence on her motivation in the advising come from other learning contexts. Because of that, some strategies related to how to deal with these factors (classmates’ proficiency, teacher’s methodology etc.) were strongly discussed in our meetings. One of these attractor states that the student reported was her difficulty in keeping up with discussions in her English classes. In that regard, the advisor asked her about the possibility of studying the subject before going to class because, in doing so, her difficulties would probably be diminished. Laura decided to implement this strategy and saw that it worked in that particular course. Because of this, she autonomously used this strategy in at least two other subjects. This behavior exemplifies the interconnection and coadaptation between the contexts where Laura’s language learning takes place.

Looking back: Laura’s language learning trajectory after advising

One of the reasons why Laura wanted to participate in language advising was to deal with her lack of motivation. Although she reports being motivated while learning English with the support of advising, her learning trajectory takes a different path when not being advised. Laura was advised during the two months in the first academic semester when her motivation was high because of the beginning of the course (see ST1B and ST1E in Figure. 2), but as soon as she observed the proficiency level of her classmates, she felt discouraged to speak in the classroom, decreasing her motivation (“When I got to university I didn’t have the same level of proficiency as my colleagues and this was very demotivating” – Laura, interview). This downward movement is also perceived in advising sessions, as previously seen in Figure 1.

After having participated in advising, Laura’s motivation decreased and settled in an attractor state of self-perceived low level of motivation. In her view, she did not adapt to her English teacher methodology and, because of this, she put less effort into studying this language at university and eventually received average grades, not the highest as planned. As Figure 2 illustrates, her motivational system shows an upward movement when a new teacher arrives. Although her grade was the same as in the previous courses, she reports to be motivated because of this new agent in her motivational system.

Figure 2. Motivational Graph Describing the Self-perceived Evolution of the Level of Laura’s Motivation in Academic Semesters

It is important to note that it was not Laura’s decision to not take part in advising sessions anymore. This happened because her advisor had to work on a different campus and could only advise her virtually. In this regard, Laura mentions that language advising was beneficial for her when face-to-face as it provided her with learning strategies to improve her language learning and also reflection about such process (“If there’s something I learned in advising was to reflect about my learning” – Laura, interview). In addition to that, she says it was important having someone to talk to in English in a more individualized and personal space, and also setting goals. However, although she acknowledges her role, she reports that if she had had more face-to-face advising sessions, her motivation would have had more chance to be high. Although such statement cannot be assured in terms of the complexity paradigm, it seems true that Laura needed an additional support to regulate her motivation.

Concluding Remarks

This paper illustrated the factors that contributed to the fluctuation of motivation of one learner, Laura, in advising in language learning sessions. It considered both Laura’s and the advisor’s perceptions about her motivational trajectory. The objectives were achieved as such factors were identified, such as task complexity, tiredness, sense of competence, teachers and peers. They influenced the fluctuation of motivation, which underwent a complex, dynamic, and non-linear evolution. In relation to the influence of advising in her motivation, the findings show that the advisor disturbed the system to an attractor state of more positive attitudes, even though that attractor state did not remain stable after language advising support. Despite that, the present study encourages more research on language advising trajectories, exploring the relation between advising and self-regulation, advising and self-esteem, and further advising and motivation.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Juliana Ribeiro and Walkyria Magno e Silva for their feedback on earlier drafts of this paper, the editors of this special issue, Jo Mynard and David McLoughlin, and the two anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions. I would like to extend my gratitude to all the language advisors of the Federal University of Pará for allowing me to learn from their experiences and reflections. A special thank goes to “Laura” for sharing her motivation, vision, dreams, fears and hopes with me.

Notes on the Contributor

Eduardo Castro is a language advisor and a lecturer at the Federal University of Pará, Brazil, where he teaches courses in applied linguistics and language pedagogy. His research interests include the psychology of language learning and teaching, language advising, motivation, autonomy, agency, and emotions using a complexity-informed approach.

References

Boo, Z., Dörnyei, Z., & Ryan, S. (2015). L2 motivation research 2005-2014: Understanding a publication surge and a changing landscape. System, 55, 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2015.10.006

Castro, E. (2018). Complex adaptive systems, language advising, and motivation: A longitudinal case study with a Brazilian student of English. System, 74, 138–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.03.004

Castro, E., & Magno e Silva, W. (2016). O efeito do aconselhamento na trajetória de aprendizagem de uma estudante de inglês [The effect of advising on the learning trajectory of a student of English]. In W. Magno e Silva & E. F. do V. Borges (Eds.), Complexidade em ambientes de ensino e aprendizagem de línguas adicionais (pp. 139–158). Curitiba: Editora CRV.

Ciekanski, M. (2007). Fostering learner autonomy: Power and reciprocity in the relationship between language learner and language learning adviser. Cambridge Journal of Education, 37(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640601179442

Davis, B., & Sumara, D. (2006). Complexity and education: Inquiries into learning, teaching, and research. New York, NY: Routlegde.

De Bot, K., Lowie, W., & Verspoor, M. (2007). A dynamic systems theory approach to second language acquisition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 10(1), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728906002732

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9–42). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Dörnyei, Z. (2014). Researching complex dynamic systems: “Retrodictive qualitative modelling” in the language classroom. Language Teaching, 47(1), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000516

Dörnyei, Z., MacIntyre, P. D., & Henry, A. (Eds.). (2015). Motivational dynamics in language learning. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ryan, S. (2015). The psychology of language learner revisited. New York, NY: Routlegde.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed.). London, UK: Pearson.

Duff, P. A. (2008). Case study research in applied linguistics. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Henry, A. (2015). The dynamics of L3 motivation: A longitudinal interview/observation-based study. In Z. Dörnyei, P. D. MacIntyre, & A. Henry (Eds.), Motivational dynamics in language learning (pp. 315–342). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Hiver, P. (2015). Attractor states. In Z. Dörnyei, P. D. MacIntyre, & A. Henry (Eds.), Motivational dynamics in language learning (pp. 20–28). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Hiver, P., & Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2016). A dynamic ensemble for second language research: Putting complexity theory into practice. Modern Language Journal, 100(4), 741–756. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12347

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

King, J. (Ed.). (2016). The dynamic interplay between context and the language learner. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Larsen-freeman, D. (2013). Complexity theory: A new way to think. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, 13(2), 369–373.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (1997). Chaos/complexity science and second language acquisition. Applied Linguistics, 18(2), 141–165.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2012). Chaos/complexity theory for second language acquisition. In The Encyclopedia of applied linguistics. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0125

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2015). Ten lessons from complexy dynamic systems theory: What is on offer. In Z. Dörnyei, P. D. MacIntyre, & A. Henry (Eds.), Motivational dynamics in language learning (pp. 11–19). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2016). Classroom-oriented research from a complex systems perspective. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 6(3), 377. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2016.6.3.2

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2017). Complexity theory: The lessons continue. In L. Ortega & Z. Han (Eds.), Complexity theory and language development: In celebration of Diane Larsen-Freeman (pp. 11–50). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Larsen-Freeman, D., & Cameron, L. (2008). Complex systems and applied linguistics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Magno e Silva, W., & Borges, E. F. do V. (Eds.). (2016). Complexidade em ambientes de ensino e de aprendizagem de línguas adicionais [Complexity in environments of additional language learning]. Curitiba: Editora CRV.

Magno e Silva, W., & Castro, E. (2018). Becoming a language learning advisor: Insights from a training program in Brazil. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 9(4), 415–424. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/dec18/silva_castro/

Magno e Silva, W., Matos, M. C. V. S. e, & Rabelo, J. A. de A. (2015). Trajetórias de aprendizagem, aconselhamento linguageiro e teoria da complexidade [Learning trajectories, language advising and complexity theory]. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, 15(3), 681–710. https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-639820156336

Mercer, S. (2013). Towards a Complexity-Informed Pedagogy for Language Learning. Revista Brasileira Linguística Aplicada, 13(2), 375–398. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-63982013005000008

Mercer, S. (2016). The contexts within me: L2 self as a complex dynamic system. In J. King (Ed.), The dynamic interplay between context and the language learner (pp. 11–28). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2007). Supporting independent learning environments: An analysis of structures and roles of language learning advisers. System, 35, 66–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2006.10.008

Mozzon-McPherson, M., & Vismans, R. (Eds.). (2001). Beyond language teaching towards language advising. London, UK: CILT.

Mynard, J., & Carson, L. (Eds.). (2012). Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context. Harlow, UK: Pearson.

Ortega, L., & Han, Z. (Eds.). (2017). Complexity theory and language development: In celebration of Diane Larsen-Freeman. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Paiva, V. L. M. de O., & Nascimento, M. do (Eds.). (2011). Sistemas adaptativos complexos: Lingua(gem) e aprendizagem [Complex adaptive systems: language and learning]. Campinas, Brazil: Pontes.

Pawlak, M. (2012). The dynamic nature of motivation in language learning: A classroom perspective. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 2(2), 249–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820903124698

Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2003). Interpretive phenomenological analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative Psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 51–80). London, UK: SAGE.

Tassinari, M. G. (2016). Emotions and feelings in language advising discourse. In C. Gkonou, D. Tatzl, & S. Mercer (Eds.), New directions in language learning psychology (pp. 71–96). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Ushioda, E. (2009). A person-in-context relational view of emergent motivation, self and identity. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 215–228). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Ushioda, E. (2011). Why autonomy? Insights from motivation theory and research. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 5(2), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2011.577536

Ushioda, E. (2016). Language learning motivation through a small lens: A research agenda. Language Teaching, 49(4), 564–577. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444816000173

Verspoor, M. (2015). Initial conditions. In Z. Dörnyei, P. D. MacIntyre, & A. Henry (Eds.), Motivational dynamics in language learning (pp. 38–46). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Verspoor, M., de Bot, K., & Lowie, W. (Eds.). (2011). A dynamic approach to second language development: Methods and techniques. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Waninge, F., Dörnyei, Z., & De Bot, K. (2014). Motivational dynamics in language learning: Change, stability, and context. Modern Language Journal, 98(3), 704–723. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12118

Yin, R. K. (2003). Application of case study research (2nd ed.). London, UK: Sage.